Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Book Review - British Intelligence in The Second World War

Încărcat de

hernan124124Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Book Review - British Intelligence in The Second World War

Încărcat de

hernan124124Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Military Intelligence

David Stafford

F.H Hinsley and C.A.G. Simkins. British Intelligence in the Second World War. Volume 4: Security and Counter-intelligence. London: HMSO, 1990. Michael Howard. British Intelligence in the Second World War. Volume 5: Strategic Deception. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990. ears ago, as a novitiate in the British diplomatic service, I learned what material to enter, and what not to enter, in the official files. One series that regularly crossed my desk consisted of reports on the state of morale in what was then still referred to as the Soviet Zone of Germany. The files included reports from various governmental sources and one day it occurred to me to add what I thought was an insightful report from a journalist that I had recently read in the press. I duly had the article clipped and marked for entry. But before it reached the registry my superior made it clear that I had breached some unwritten rule. The files, he indicated, should consist solely of our own material. So out went the journalist, along with his independent and unofficial eye. I always try to remember this incident when working in government archives. It's only too easy to forget that the official files are themselves selections, created by human hand, and that the "truths" they contain are partial, incomplete, and subjective. So they rarely, if ever, tell the whole story, and that which they do relate, while essential to know, is inevitably weighted. If historians had helped create the files in the first place they would know how arbitrary and fictional their contents can be! This, as you will see, is relevant to what I have to say below. But first, a thrilling tale of wartime daring do.

92

Sometime during the winter of 1943 a young Venezuelan working as a German double agent arrived in Ottawa. Before the year was out he was sending regular letters using secret ink to his Abwehr masters. Late the next year his communications link improved dramatically with the arrival of a wireless transmitter. This was brought to him by another Abwehr agent, "Fred," a Gibraltese. "Fred" was an interesting case. Forcibly evacuated from the Rock along with the rest of the civilian population, he had ended up as a waiter in Soho. Then, mobilized by the Ministry of Labour, he toiled at various menial NAAFT jobs along the south coast of England. Increasingly disgruntled, he had got in touch with the Abwehr and reported generously on various p r e p a r a t i o n s for Operation "Overlord." His big coup came in J u n e 1944. On the eve of the Normandy landings he passed a vital piece of information. J u s t three days before, he reported, the Third Canadian Division had been issued cold rations and vomit bags. Now, it was rumoured, it had already embarked across the Channel. It was a message that, had it arrived early enough, could have alerted the Germans before the first Allied troops hit the beaches. But because of a slip-up by the Abwehr it was not received until two hours after the invasion force had actually landed. Still, the report enhanced "Fred's" reliability, and soon he smuggled himself on board a merchant ship bound for Canada. Once here, he linked up with the Venezuelan, and the two men maintained

wireless contact with the Abwehr until midApril 1945. In the last of its messages the Hamburg station instructed its agents to divide the remaining money in its funds between themselves and take all precautions for their own safety. Undoubtedly, we can surmise, it also wished them good luck. The adventures of "Fred" and the Venezuelan have remained obstinately unknown in Canada, but then that's hardly surprising. For neither man actually existed in real life, and there never was a transmitter reporting from Ottawa to Hamburg. The men, their network, and their operations were imaginary creations dreamed up by British counter-intelligence to help smoke out any real Abwehr operations on this side of the Atlantic. The Venezuelan was known to his MI5 controllers by the codename Moonbeam, while "Fred" the Gibraltese was referred to as Chamillus. Both were national agents of the equally national network of double agents operated by the Spaniard, J u a n Pujol Garcia, whom we now know as Garbo - the most remarkable and creative of all double agents run during the Second World War. The Moonbeam operation was the only successful double cross operation run in Canada. Two other, non-fictitious (ie. involving real people) attempts failed. The first involved Watchdog, a German spy who landed on the Gaspe peninsula and was immediately captured by the RCMP. Early in 1941, after MI5 sent an officer from Britain to supervise the operation, Watchdog was used as a double agent. But after eight months the operation was closed down. A similar operation transmitting from Toronto was terminated at about the same time for the same reasons. These Canadian episodes are essentially footnotes in the much larger story that emerges from the final two volumes of the official history of British Intelligence in the Second World War. 1 But in telling ways they illustrate both the strengths and weaknesses not just of these particular volumes but also of the series as a whole. Successful deception could only be built on the foundation of good intelligence and good security. The former enabled British planners to enter the mind of the enemy and to monitor

the success of their efforts. The cracking of the Abwehr hand cipher, in December 1940, then of its Enigma machine cipher a year later, made all t h i s possible. Good security guaranteed concealment and ensured that no word of deception, double cross, or regular military operations leaked to the enemy. It is an impressive story and these volumes provide a mass of evidence that all students of the war will need to consult in the future. Yet, after reading them, I return to my own experience with the files. Both volumes have their limits. Many historians have complained that the series is too dry, that names are not mentioned, that credit is not given where credit is due. That's true, but other aspects of these official histories are more important. Take Howard's volume, for example. It is written with his customary grace and clarity, but for a decade was held back from publication at the whim of Mrs. Thatcher. The result is that it neither integrates nor refers to the considerable work done by historians on deception in the later 1970s and t h r o u g h o u t the 1980s. Inevitably, therefore, much of it already seems familiar. And Howard readily admits this himself when he notes that his volume should not be taken to be the last word. It's not clear whether the Hinsley/Simkins volume suffered likewise. But it too covers ground that independent historians have covered elsewhere. The imaginary operations in Canada illustrate the point. Both volumes refer extensively to Garbo and his network. Yet it was from neither that I learned that agent "Fred's" codename was Chamillus. That comes from Garbo's own postwar account, published in 1985, which contains much detailed information that can only have come from access to the operations files.2 Garbo also makes an important claim for the Chamillus/Moonbeam operation namely that the Abwehr provided it with a new high-grade cipher, a copy of which was delivered straight to CCHQ at Bletchley. Yet neither official volume refers to this, nor does the Hinsley/Simkins volume refer to Garbo's own book at all. This is particularly odd given that in the early chapters of the volume there are many footnoted references to scholarly books and articles that appeared up to the later 93

1980s. As the volume proceeds, however, such references disappear altogether. Did the authors grow tired perhaps, or was there nothing of interest in the scholarly literature that referred to the material in the later chapters? Or was it that the volumes were hurriedly put to bed (as its abrupt and inconclusive ending would seem to indicate)? The omission is odd, but certainly not as odd as the most glaring of all. For a volume devoted to British security and counter-intelligence it can only be an incomplete and highly weighted account that fails once to mention Anthony Blunt, Guy Burgess or Kim Philby, significant wartime employees of MI5 and MI6 respectively. But then, undetected as they were during the war, there must be no wartime files on them. And if they're not in the files, they can't be important, can they?

Notes

1. British Intelligence in the Second World War. Volume 4, Security and Counter-intelligence, by F.H. Hinsley a n d C.A.G. S i m k i n s (London: HMSO, 1990): Volume 5, Strategic Deception, by Michael H o w a r d (NY: C a m b r i d g e University P r e s s , 1990). 2. J u a n Pujol, with Nigel West. Garbo. (London: Weidenfeld a n d Nicolson, 1985).

David Stafford's books include Britain and European Resistance 1940-45 and Camp X: Canada's School for Secret Agents. He was Executive Director of the Canadian Federation of International Affairs until the summer of 1992. He is currently at the University of Edinburgh. Dr. Stafford is a Contributing Editor for CMH and will also write a regular book column.

94

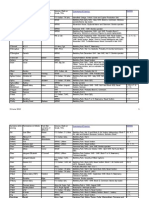

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Bletchley List JKDocument21 paginiBletchley List JKeliahmeyerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Black Feminism, The CIA and Gloria Steinem.Document7 paginiBlack Feminism, The CIA and Gloria Steinem.Min Hotep Tzaddik BeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- SOE & A W SheppardDocument10 paginiSOE & A W SheppardΜπάμπης ΦαγκρήςÎncă nu există evaluări

- Folkert Van Koutrik (German Agent in SIS & MI-5)Document4 paginiFolkert Van Koutrik (German Agent in SIS & MI-5)GTicktonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bletchley List XyzDocument3 paginiBletchley List XyzeliahmeyerÎncă nu există evaluări

- OKHRANA - The Paris Operations of The Russian Imperial PoliceDocument20 paginiOKHRANA - The Paris Operations of The Russian Imperial PoliceoraberaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 'I Spied Spies' BRDocument7 pagini'I Spied Spies' BRalifahad80Încă nu există evaluări

- The Devil's Workshop - A Memoir of The Nazi Counterfeiting Operation by Adolf BurgerDocument445 paginiThe Devil's Workshop - A Memoir of The Nazi Counterfeiting Operation by Adolf BurgerBiblioteca Băile Govora100% (2)

- SpymasterDocument481 paginiSpymasterninoyako100% (1)

- WeeblylookbookDocument56 paginiWeeblylookbookapi-411493600Încă nu există evaluări

- History of Infiltration Into France 1940-1945 PDFDocument94 paginiHistory of Infiltration Into France 1940-1945 PDFcuti100% (1)

- The Unholy Alliance - Du Pont, GM and The NazisDocument5 paginiThe Unholy Alliance - Du Pont, GM and The Nazisfileandclaw32250% (4)

- Spies and Secret Service - The Story of Espionage, Its Main Systems and Chief ExponentsDe la EverandSpies and Secret Service - The Story of Espionage, Its Main Systems and Chief ExponentsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Office of Strategic Services (OSS)Document7 paginiThe Office of Strategic Services (OSS)farooq hayatÎncă nu există evaluări

- British Intelligence and the Formation Of a Policy Toward Russia, 1917-18: Missing Dimension or Just Missing?De la EverandBritish Intelligence and the Formation Of a Policy Toward Russia, 1917-18: Missing Dimension or Just Missing?Încă nu există evaluări

- CIA Files Relating To Heinz Felfe SS Officer and KGB SpyDocument17 paginiCIA Files Relating To Heinz Felfe SS Officer and KGB SpyJimmy LeonardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Valerie Pettit Obituary - Register - The Times PDFDocument13 paginiValerie Pettit Obituary - Register - The Times PDFJohnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Romeo SpyDocument247 paginiRomeo SpygichuraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culper Spy RingDocument9 paginiCulper Spy Ringapi-274404034Încă nu există evaluări

- Burn After Reading: The Espionage History of World War IIDe la EverandBurn After Reading: The Espionage History of World War IIEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (6)

- Miners Strike ResearchDocument4 paginiMiners Strike Researchapi-545853955Încă nu există evaluări

- 2020.01.07 Alan Pemberton - A Brief SynopsisDocument5 pagini2020.01.07 Alan Pemberton - A Brief SynopsisFaireSansDireÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Fuss About SutchDocument242 paginiThe Fuss About SutchMark McIvor100% (1)

- 2 MolehuntDocument127 pagini2 MolehuntIon VasilescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2015 Russian Spy RingDocument26 pagini2015 Russian Spy RingPolly SighÎncă nu există evaluări

- SLC 35F - Virginia Hall - Leadership EssayDocument9 paginiSLC 35F - Virginia Hall - Leadership EssayAngela HoltbyÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Intelligence CorpsDocument5 paginiHistory of Intelligence Corpsjamiesmith909Încă nu există evaluări

- Along Parallel Lines: A History of the Railways of News South Wales 1850-1986De la EverandAlong Parallel Lines: A History of the Railways of News South Wales 1850-1986Încă nu există evaluări

- In the Shadows: The extraordinary men and women of the Intelligence CorpsDe la EverandIn the Shadows: The extraordinary men and women of the Intelligence CorpsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Some British Experiences With Cipher Machines FINALDocument9 paginiSome British Experiences With Cipher Machines FINALDAVID KINGÎncă nu există evaluări

- British Intelligence in The Second World WarDocument5 paginiBritish Intelligence in The Second World War1013133% (3)

- U-Oct 1993 - of Moles - Molehunters - A Review of Counterintelligence Literature - 1977-92 - V2Document92 paginiU-Oct 1993 - of Moles - Molehunters - A Review of Counterintelligence Literature - 1977-92 - V2KemalCindorukÎncă nu există evaluări

- Another Herbert O Yardley Mystery - The PondDocument4 paginiAnother Herbert O Yardley Mystery - The PondQuibus_LicetÎncă nu există evaluări

- GEHLEN Reinhard CIA File VOL 6Document289 paginiGEHLEN Reinhard CIA File VOL 6channel view100% (1)

- Reader CIDocument1.292 paginiReader CITaletosRekolosÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Origins of Nsa: Center For Cryptologic History National Security Agency Fort George G. Meade MarylandDocument7 paginiThe Origins of Nsa: Center For Cryptologic History National Security Agency Fort George G. Meade MarylandsinistergripÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frontline Intelligence in WW2 - (I) German Intelligence CollectionDocument8 paginiFrontline Intelligence in WW2 - (I) German Intelligence CollectionkeithellisonÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of The Special Air ServiceDocument15 paginiHistory of The Special Air ServiceFidel Athanasios100% (1)

- Italy at War and the Allies in the WestDe la EverandItaly at War and the Allies in the WestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Berlin Teufelsberg: Outpost in the Middle of Enemy TerritoryDe la EverandBerlin Teufelsberg: Outpost in the Middle of Enemy TerritoryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Au Army 1269Document43 paginiAu Army 1269AVRM Magazine StandÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Federal Security Service of The Russian Federation, by Gordon Bennett (March, 2000)Document55 paginiThe Federal Security Service of The Russian Federation, by Gordon Bennett (March, 2000)don_ro_2005Încă nu există evaluări

- Nisei LinguistsDocument534 paginiNisei LinguistsBob Andrepont100% (1)

- US Role Adriatic 1918-21Document43 paginiUS Role Adriatic 1918-21Slobodan CekicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ireland's Secret War: Dan Bryan, G2 and the Lost Tapes that Reveal The Hunt for Ireland's Nazi SpiesDe la EverandIreland's Secret War: Dan Bryan, G2 and the Lost Tapes that Reveal The Hunt for Ireland's Nazi SpiesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bletchley List UvDocument4 paginiBletchley List UveliahmeyerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allied Espionage and Sabotage in Sweden in WWIIDocument16 paginiAllied Espionage and Sabotage in Sweden in WWIIstefstefanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geocurrents - Info-Ralph Peters Thinking The Unthinkable PDFDocument2 paginiGeocurrents - Info-Ralph Peters Thinking The Unthinkable PDFshahidacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agent Paterson SOE: From Operation Anthropoid to France: The Memoirs of E.H. van MaurikDe la EverandAgent Paterson SOE: From Operation Anthropoid to France: The Memoirs of E.H. van MaurikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bloody Red Tabs: General Officer Casualties of the Great War 1914–1918De la EverandBloody Red Tabs: General Officer Casualties of the Great War 1914–1918Încă nu există evaluări

- Surprise And Deception In The Early War Years, 1940-1942De la EverandSurprise And Deception In The Early War Years, 1940-1942Încă nu există evaluări

- Gallipoli Letter 1915 Written by MurdochDocument10 paginiGallipoli Letter 1915 Written by MurdochertwuyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Role Of The Office Of Strategic Services In Operation TorchDe la EverandRole Of The Office Of Strategic Services In Operation TorchÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Deeds Of Valiant Men: A Study In Leadership. The Marauders In North Burma, 1944De la EverandThe Deeds Of Valiant Men: A Study In Leadership. The Marauders In North Burma, 1944Încă nu există evaluări

- Bletchley List oDocument5 paginiBletchley List oeliahmeyerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Office Of The Strategic Services Operational Groups In France During World War II, July-October 1944De la EverandOffice Of The Strategic Services Operational Groups In France During World War II, July-October 1944Încă nu există evaluări

- The Question of The AdriaticDocument9 paginiThe Question of The AdriaticHalil İbrahim Şimşek100% (1)

- Full Annotated BibliographyDocument12 paginiFull Annotated BibliographyMisbah KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dundee War Hospitals During The Great War 1914-1918De la EverandDundee War Hospitals During The Great War 1914-1918Evaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Barker Partisan Warfare in Carinthia enDocument18 paginiBarker Partisan Warfare in Carinthia enPeter KimbelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alex Jones STRATFOR AgentDocument6 paginiAlex Jones STRATFOR AgentProfessor WatchlistÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Brief History of NinjutsuDocument4 paginiA Brief History of NinjutsuGoran SipkaÎncă nu există evaluări

- State Secret Chapter 2Document17 paginiState Secret Chapter 2bsimpichÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lawson - The French Resistance - The True Story of The Underground War Against The Nazis (1984)Document182 paginiLawson - The French Resistance - The True Story of The Underground War Against The Nazis (1984)isaac_naseer100% (1)

- The Tragic Love Story of Marti and Schaeffer CoxDocument32 paginiThe Tragic Love Story of Marti and Schaeffer CoxLoneStar1776Încă nu există evaluări

- Spy Masters of RAW, Some Explosive Revelations and A Few Books Worth Remembering - IBNLiveDocument5 paginiSpy Masters of RAW, Some Explosive Revelations and A Few Books Worth Remembering - IBNLiveAnkhein Kholiye Doston100% (1)

- Reign of TerrorDocument2 paginiReign of Terrorapi-215124270Încă nu există evaluări

- Infiltration TacticsDocument4 paginiInfiltration TacticsChristopher BurkeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foreign Intelligence and The Historiography of The Cold WarDocument36 paginiForeign Intelligence and The Historiography of The Cold WarFabio ChavesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uk Intelligence and Security ReportDocument61 paginiUk Intelligence and Security ReporteliahmeyerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Get TRDocDocument209 paginiGet TRDoc10131Încă nu există evaluări

- Ecfr 169 - Putins Hydra Inside The Russian Intelligence Services 1513 PDFDocument20 paginiEcfr 169 - Putins Hydra Inside The Russian Intelligence Services 1513 PDFtayo_bÎncă nu există evaluări

- Malik Khaalis Case DocumentsDocument186 paginiMalik Khaalis Case Documentssavannahnow.comÎncă nu există evaluări

- Albanese 2017Document16 paginiAlbanese 2017Stratis BournazosÎncă nu există evaluări

- New World Order Elite Think Tanks - David GuyattDocument11 paginiNew World Order Elite Think Tanks - David Guyattgym-boÎncă nu există evaluări

- CIA Document On The MHCHAOS ProgramDocument3 paginiCIA Document On The MHCHAOS ProgramWally ConleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Egyptian Intelligence Service (A History of The Mukhabarat, 1910-2009) - (2010, Routledge) (10.4324 - 9780203854549) - Libgen - LiDocument284 paginiThe Egyptian Intelligence Service (A History of The Mukhabarat, 1910-2009) - (2010, Routledge) (10.4324 - 9780203854549) - Libgen - LiMehmet ŞencanÎncă nu există evaluări

- JFK, Indonesia, CIA and Freeport SulphurDocument13 paginiJFK, Indonesia, CIA and Freeport SulphurArif BaskoroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social EngineeringDocument4 paginiSocial EngineeringEfthymios HadjimichaelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Operation Majestic 12Document9 paginiOperation Majestic 12luvpuppy_uk100% (1)

- Ireland :germany 1920 R.casement 62 Page Doc On German/Sinn Fein RelationsDocument62 paginiIreland :germany 1920 R.casement 62 Page Doc On German/Sinn Fein RelationspeterniamhÎncă nu există evaluări

- The CIA ListsDocument128 paginiThe CIA Liststrueprophet3Încă nu există evaluări

- Who Leaked Classified US Info On Indo-Pak War in 1971 (2010)Document3 paginiWho Leaked Classified US Info On Indo-Pak War in 1971 (2010)Canary Trap100% (1)

- State Secret: PrefaceDocument47 paginiState Secret: PrefacebsimpichÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ten Commandments of Espionage PDFDocument8 paginiTen Commandments of Espionage PDFlionel1720Încă nu există evaluări