Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

What Police Can Do

Încărcat de

Oscar Contreras VelascoDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

What Police Can Do

Încărcat de

Oscar Contreras VelascoDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

American Academy of Political and Social Science

What Can Police Do to Reduce Crime, Disorder, and Fear? Author(s): David Weisburd and John E. Eck Source: Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 593, To Better Serve and Protect: Improving Police Practices (May, 2004), pp. 42-65 Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. in association with the American Academy of Political and Social Science Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4127666 . Accessed: 09/04/2013 02:57

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Sage Publications, Inc. and American Academy of Political and Social Science are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

What Can Police Do to Reduce Crime, Disorder, and

Fear?

By DAVID WEISBURD and

The authors review research on police effectiveness in reducing crime, disorder, and fear in the context of a typologyof innovationin police practices. That typology emphasizes two dimensions: one concerning the diversity of approaches, and the other, the level offocus. The authors find that little evidence supports the standard model of policing-low on both of these dimensions. In contrast, research evidence does support continued investment in police innovations that call for greater focus and tailoring of police efforts, combined with an expansionof the tool box of policing beyond simple law enforcement. The strongest evidence of police effectiveness in reducing crime and disorder is found in the case of geographicallyfocused police practices, such as hot-spots policing. Community policing practices are found to reduce fearof crime, but the authorsdo not find consistent evidence that community policing (when it is implemented without models of problem-oriented policing) affects either crime or disorder.A developing body of evidence points to the effectiveness of problemoriented policing in reducing crime, disorder,and fear. More generally, the authors find that many policing practices applied broadlythroughout the United States either have not been the subject of systematic research or have been examinedin the context of researchdesigns that do not allow practitionersor policy makersto draw very strong conclusions. Keywords: police; evaluations; crime; disorder; hot spots; problem-oriented policing; community policing

E.ECK JOHN

decadehasbeen the mostinnovative The past in American Such approachesas community policing, problemoriented policing, hot-spots policing, and broken-windowspolicing either emerged in the agenciesat that time. The changesin American

David Weisburd is a professor of criminology at the Hebrew UniversityLaw Schooland a professorof criminology and criminaljustice at the University of Maryland-College Park.He is also a seniorfellow at the Police Foundation in Washington,D.C. John E. Eck is a professorin the Division of CriminalJustice at the Universityof Cincinnati.

DOI: 10.1177/0002716203262548

period

policing.

1990s or came to be widely adopted by police

42

ANNALS, AAPSS, 593, May 2004

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REDUCING AND FEAR CRIME,DISORDER,

43

and resispolicingwere dramatic.From an institutionknownfor its conservatism tance to change,policingsuddenlystood out as a leaderin criminal justiceinnovaThis new in new to and tion. openness innovation widespreadexperimentation could be that were of a in American renewed confidence practices part policing foundamongnot onlypoliceprofessionals the and but alsoscholars generalpublic. While there is much debate over whatcaused the crime dropof the 1990s, many police executives,police scholars,and laypeople lookedto new policingpractices as a primary (Bratton1998;Eck and Maguire2000; Kellingand Sousa explanation 2001). At the same time that manyin the United Statestouted the new policingas an forimprovements in communitysafety,manyscholarsandpolice proexplanation fessionalsidentifiedthe dominantpolicingpracticesof earlierdecadesas wasteful and ineffective.This criticismof the "standard model"of policingwas part of a more generalcritiqueof the criminaljustice systemthat emerged as earlyas the mid-1970s(e.g., see Martinson 1974).As in otherpartsof the criminal justice system, a series of studiesseemed to suggestthat such standard practicesas random or had little impacton calls for service to preventivepatrol rapidresponse police crime or on fear of crime in Americancommunities(e.g., see Kellinget al. 1974; Spelmanand Brown 1981). By the 1990s, the assumptionthat police practices were ineffectivein combatingcrime was widespread(Bayley 1994; Gottfredson andHirschi1990),a factorthatcertainly at helpedto spawnrapidpolice innovation that time. In this article,we revisitthe central assumptionsthat have underlainrecent Americanpolice innovation.Does the researchevidence supportthe view that standardmodels of policingare ineffectivein combatingcrime and disorder?Do elements of the standard model deservemore carefulstudybefore they are abandoned as methods of reducingcrime or disorder?Do recent police innovations hold greaterpromise of increasingcommunitysafety,or does the researchevidence suggestthat they are popularbut actuallyineffective?Whatlessonscan we drawfrom researchaboutpolice innovationin reducingcrime, disorder,and fear overthe lasttwo decades?Does suchresearchlead to a moregeneralset of recommendationsfor Americanpolicingor for police researchers? Our articleexaminesthese questionsin the contextof a reviewof the research evidence aboutwhatworksin policing.Ourfocus is on specific elements of community safety:crime, fear, and disorder.We begin by developinga typologyof police practicesthatis used in ourarticleto organizeandassessthe evidenceabout

NOTE: Our review of police practices in this paper derives from a subcommittee report on police effectiveness that was partof a largerexaminationof police researchand practices undertaken by the NationalAcademyof Sciences and chaired by Wesley G. Skogan.We cochaired the subcommittee chargedwith police effectiveness which also included David Bayley,Ruth Peterson, and Lawrence Sherman.While we draw heavily from that review, our analysisalso extends the critique and represents our interpretationof the findings. Our review has benefited much from the thoughtful comments of Carol Petrie and Kathleen Frydl of the National Academy of Sciences. We also want to thank Nancy Morrisand Sue-Ming Yangfor their help in preparation of this paper.

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

44

THE ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY

police effectiveness.We then turnto a discussionof how thatevidencewas evaluated and assessed.Whatcriteriadid we use for distinguishing the value of studies for comingto conclusionsaboutthe effectivenessof police practices?How didwe decide when the evidencewaspersuasive enoughto drawmoregeneralstatements about specific programsor strategies?Our review of the evidence follows. Our approachis to identifywhat existingstudies say about the effects of core police in thisway,we concludewith the research literature practices.Havingsummarized a more general synthesis of the evidence reviewed and a discussion of its implicationsfor police practiceand researchon policing.

The StandardModel of Policing and Recent Police Innovation:A Typologyof Police Practices

whathascome criticized Overthe pastthreedecades,scholars haveincreasingly to be consideredthe standardmodel of police practices(Bayley1994; Goldstein 1990;VisherandWeisburd1998).This model relies generallyon a "one-size-fitsall"applicationof reactivestrategiesto suppresscrime and continues to be the dominantform of police practicesin the United States. The standardmodel is basedon the assumption thatgenericstrategiesforcrimereductioncanbe applied a throughout jurisdictionregardlessof the level of crime, the natureof crime, or other variations. Such strategiesas increasingthe size of police agencies,random all across patrol partsof the community, rapidresponseto callsfor service,generand allyappliedfollow-upinvestigations, generallyappliedintensiveenforcement and arrestpolicies are all examplesof this standardmodel of policing. Because the standard model seeks to providea generalizedlevel of police serit has often been criticizedas focused more on the means of policingor the vice, resourcesthatpolicebringto bearthanon the effectivenessof policingin reducing of prevenin the application or fear(Goldstein1979).Accordingly, crime,disorder, will often meamodel tive patrolin a city,police agencies followingthe standard street at on the are sure successin termsof whethera certainnumberof patrolcars calls citizen certaintimes. In agenciesthatseek to reducepolice responsetimesto for service,improvements in the averagetime of responseoften become a primary model canlead measureof police agencysuccess.In this sense, usingthe standard police agenciesto become moreconcernedwith how police servicesare allocated than whetherthey have an impacton public safety. law This modelhasalsobeen criticizedbecauseof its relianceon the traditional enforcementpowersof police in preventingcrime (Goldstein1987). Police agencies relying upon the standard model generally employ a limited range of oriented towardenforcement,and make relatively approaches,overwhelmingly little use of institutionsoutside of policing (with the notable exceptionof other

parts of the criminal justice system). "Enforcing the law"is a central element of the standard model of policing, suggesting that the main tools available to the police, or legitimate for their use, are found in their law enforcement powers. It is no coinci-

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REDUCING CRIME, DISORDER, AND FEAR

45

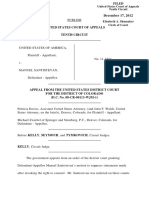

FIGURE 1 DIMENSIONS OF POLICING STRATEGIES

.......

.. ......

4j,

Community Problem-

low

Level of Focus

high

dence that police departments are commonly referred to as "law enforcement agencies." In the standard model of policing, the threat of arrest and punishment forms the core of police practices in preventing and controlling crime. Recent innovations in policing have tended to expand beyond the standard model of policing along two dimensions. Figure 1 depicts this relationship. The vertical axis of the figure, diversity of approaches, represents the content of the practices employed. Strategies that rely primarily on traditional law enforcement are low on this dimension. The horizontal axis, level offocus, represents the extent of focus or targeting of police activities. Strategies that are generalized and applied uniformly across places or offenders score low on this dimension. Innovations in policing over the last decade have moved outward along one or both of these dimensions. This point can be illustrated in terms of three of the dominant trends in innovation over the last two decades: community policing, hot-spots policing, and problem-oriented policing. We note at the outset that in emphasizing specific components of these innovations, we are trying to illustrate our typology, although in practice, the boundaries between approaches are seldom clear and often overlap

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

46

THE ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY

in theirapplications in realpolice settings.Wewill discussthis pointin fullerdetail in our examination of specific strategieslaterin our article. of the Community policing,perhapsthe mostwidelyadoptedpolice innovation last decade, is extremelydifficultto define:Its definitionhasvariedover time and 1988). amongpolice agencies(Eck and Rosenbaum1994;Greeneand Mastrofski One of the principalassumptionsof communitypolicing, however,is that the out the police of resourcesin carrying police can drawfroma muchbroaderarray functionthanis foundin the traditional lawenforcementpowersof the police. For example,most scholarsagreethatcommunitypolicingshouldentailgreatercommunityinvolvementin the definitionof crime problemsand in police activitiesto and Bayley1986;Weisburd, preventand controlcrime (Goldstein1990;Skolnick and 1988). McElroy, Hardyman Community policingsuggestsa relianceon a more crime control draws on the resourcesof the publicas well as that community-based in our the police.Thus,it is placedhighon the dimensionof diversity of approaches when It lies to of because commuthe left focus on the dimension of level typology. nitypolicingis employedwithoutproblemsolving(see later),it providesa common set of servicesthroughouta jurisdiction. Hot-spotspolicing (Braga2001; Shermanand Weisburd1995;Weisburdand to crimecontrolthatillustrates new approach 2003) representsanimportant Braga innovationon our second dimension,level of focus. It demandsthat the police wherecrimeis concentratedandthen identifyspecificplacesin theirjurisdictions focus resources at those locations. When only traditional law enforcement suchas directedpatrolareusedin bringing attentionto suchhot spots, approaches but lowon thatof diveris on of level of focus the dimension hot-spotspolicing high of sity approaches. Problem-orientedpolicing (Goldstein 1990) expands beyond the standard model in termsof both focus and the tools that are used. Problem-oriented policing, as its namesuggests,callsforthe police to focuson specificproblemsandto fit their strategiesto the problemsidentified. It thus departsfrom the generalized one-size-fits-allapproachof the standardmodel and calls for tailor-madeand focusedpolice practices.But in definingthose practices,problem-oriented policlaw enforcement ing also demandsthat the police look beyond their traditional powersand drawupon a host of other possible methodsfor addressingthe problems they define. In problem-orientedpolicing, the tool box of policing might includecommunityresourcesor the powersof other governmentagencies.

Evaluatingthe Evidence

modelof policing Beforewe turnto whatour reviewtells us aboutthe standard we used in assessandrecentpoliceinnovation, it is important to layout the criteria when studies ing the evidencewe reviewed.Thereis no hardrule fordetermining when there is more indicate line to reliable or or clear valid results, any provide scisocial evidence to come conclusion. to an Nonetheless, enough unambiguous

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REDUCING CRIME, DISORDER, AND FEAR

47

entists generallyagree on some basic guidelinesfor assessingthe strengthof the evidence available. criterionrelatesto what Perhapsthe mostwidelyagreed-upon is often referredto as internalvalidity(Shermanet al. 2002;Weisburd,Lum, and Petrosino2001). Researchdesignsthatallowthe researcher to makea stronger link between the interventions or programs examinedand the outcomesobservedare generallyconsideredto providemorevalidevidencethanare designsthatprovide for a more ambiguousconnectionbetween cause and effect. In formalterms,the formerdesignsare consideredto have higherinternalvalidity. In reviewingstudcriterionfor assessingthe strengthof the ies, we used internalvalidityas a primary evidence provided.

Using the standard model can lead police agencies to become more concerned with how police services are allocated than whether they have an impact on public safety.

Researchersgenerallyagree that randomizedexperimentsprovide a higher level of internal thando nonexperimental studies(see, e.g., Boruch,Victor, validity andCecil 2000;CampbellandBoruch1975;CookandCampbell1979;Farrington 1983; Feder and Boruch 2000; Shadish,Cook, and Campbell 2002; Weisburd 2003). In randomizedexperiments,people or places are randomlyassignedto treatmentand control or comparisongroups.This means that all causes, except treatment itself, can be assumed to be equally distributedamong the groups. if an effect for an intervention can conclude is found,the researcher Accordingly, with confidencethatthe causewas the intervention itself andnot some otherconfoundingfactor. Anotherclass of studies,referredto here as quasi-experiments, typicallyallow for less confidencein makinga linkbetween the programs or strategiesexamined andthe outcomesobserved(CookandCampbell1979).Quasi-experiments generallyfall into three classes.In the firstclass,the studycomparesan "experimental" groupwitha controlor comparison group,but the subjectsof the studyarenot ranto a long the In domlyassigned categories. the second classof quasi-experiments, series of observationsis made before the treatment,and anotherlong series of observationsis made after the treatment.The third class of quasi-experiments combinesthe use of a controlgroupwith time-seriesdata.This latterapproachis research. generallyseen to providethe strongestconclusionsin quasi-experiment

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

48

THE ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY

Quasi-experimental designsare assumedto have a lower level of internalvalidity than are randomizedexperimental studies, however,because the researchercan never be certainthat the comparison conditionsare trulyequivalent. Finally, studies that rely only on statistical controls-generally termed or correlationaldesigns-are often seen to lead to the weakest nonexperimental level of internalvalidity (Cook and Campbell 1979; Shermanet al. 1997). In nonexperimentalresearch,neither researchersnor policy makersintentionally variation to test for outcomes.Rather, observenatural researchers varytreatments in outcomesandexaminethe relationships andpolice pracbetweenthatvariation tices. For example,when tryingto determine if police staffinglevels influence crime, researchersmight examine the relationshipbetween staffinglevels and crimeratesacrosscities.The difficulty otherfactors is apparent: withthisapproach To address levels. influence and crime also confounded with be may staffing may It is thisconcern,researchers factors these other to control for statistically. attempt researcher the or unmeasured that unknown causes by generallyagreed,however, arelikelyto be a seriousthreatto the internalvalidityof these correlational studies (Feder and Boruch2000; Kunzand Oxman1998; Pedhazer1982). In our review,we rely stronglyon these general assessmentsof the abilityof researchto makestatementsof highinternalvalidity the practicesevaluregarding in assessingthe ated. However,we also recognizethatothercriteriaare important randomized that of research. While academics experstrength generallyrecognize iments have higher internalvaliditythan nonrandomizedstudies, a number of scholarshave suggestedthe resultsof randomizedfield experimentscan be compromised by the difficultyof implementingsuch designs (Cornishand Clarke in assessingthe evidence, 1972;Eck 2002; Pawsonand Tilley 1997). Accordingly, we also took into account the integrityof the implementationof the research design. Evenif a researcher canmakea verystronglinkbetweenthe practicesexamined in a specific study and their influence on crime, disorder,or fear, if one cannot make inferences from that study to other jurisdictionsor police practicesmore mostsocialscientists then the findingswill not be veryuseful. Moreover, generally, agreethatcautionshouldbe used in drawingstrongpolicyconclusionsfroma single study, no matter how well designed (Manski2003; Weisburdand Taxman 2000). For these reasons,we took into account such additionalfactorsrelatedto our abilityto generalizefromstudyfindingsin drawingour conclusions.

What Worksin Policing Crime, Disorder, and Fear of Crime

Below,we reviewthe evidenceon whatworksin policingusingthe criteriaoutlined above. In organizing our review,we rely on our typologyof police practices andthusdivideourdiscussioninto foursections,representing the fourbroadtypes of police approachessuggestedin our discussionof Figure 1. For each type, we

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REDUCING CRIME, DISORDER, AND FEAR

49

tells whatthe researchliterature thatsummarizes beginwith a generalproposition andfearof us aboutthe effectivenessof thatapproach in reducingcrime,disorder, crime. of 1:Thestandard hasreliedon the uniform modelof policing provision Proposition andthe lawenforcement policeresources powersof the policeto preventcrime anddisorder allpartsof thejurisdictions across a widearray of crimesandacross that police serve. Despite the continuedrelianceof manypolice agencieson areeffective thesestandard littleevidenceexiststhatsuchapproaches practices, in controlling crimeanddisorder fearof crime. or in reducing In our reviewof the standard model of policing,we identifiedfive broadstrategies thathavebeen the focusof systematicresearchoverthe lastthree decades:(1) the size of police agencies;(2) randompatrolacrossallpartsof the comincreasing (3) munity; rapidresponse to calls for service; (4) generalizedinvestigationsof crime;and (5) generallyappliedintensiveenforcementand arrestpolicies. Increasing the size of police agencies Evidencefromcase studiesin whichpolice havesuddenlyleft duty(e.g., police strikes)shows that the absence of police is likelyto lead to an increasein crime and Eck2002). Whilethese studiesaregenerallynot verystrongin their (Sherman their conclusionsare consistent.But the findingthat removingall police design, will lead to more crime does not answerthe primaryquestionthat most scholars increasesin the andpolicymakersare concernedwith-that is, whethermarginal or fear.The evinumberof police officerswillleadto reductions in crime,disorder, dence in this case is contradictory and the studydesigns generallycannotdistinareassoguishbetweenthe effectsof police strengthandthe factorsthatordinarily structures. ciated with police hiringsuch as changes in tactics or organizational Most studies have concludedthat variationsin police strengthover time do not affect crime rates (Chamlin and Langworthy1996; Eck and Maguire 2000; Niskanen1994;vanTulder1992).However,two recentstudiesusingmoresophisticated statistical increasesin the numberof police designs suggestthat marginal are relatedto decreasesin crime rates (Levitt 1997; Marvelland Moody 1996). Randompatrol across all parts of the community Randompreventivepatrolacrosspolicejurisdictions hascontinuedto be one of the most enduringof standard police practices.Despite the continueduse of ranthispracdompreventivepatrolby manypolice agencies,the evidencesupporting tice is very weak, and the studies reviewedare more than a quartercenturyold.

Two studies, both using weaker quasi-experimental designs, suggest that random preventive patrol can have an impact on crime (Dahmann 1975; Press 1971). A much larger scale and more persuasive evaluation of preventive patrol in Kansas City found that the standard practice of preventive patrol does not reduce crime,

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

50

THE ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY

disorder,or fear of crime (Kellinget al. 1974). However,while this is a landmark study,the validityof its conclusionshas also been criticizedbecause of methodMedicalResearchFoundation ologicalflaws(LarsonandCahn1985;Minneapolis 1976; Shermanand Weisburd1995). Rapid response to callsfor service A thirdcomponentof the standard modelof policing,rapidresponseto callsfor service, has also not been shown to reduce crime or even to lead to increased chancesof arrestin mostsituations. behindrapid The crime-reduction assumption will if is that the to scenes crime response apprehend police get rapidly,they offenders,thusprovidinga generaldeterrentagainstcrime. No studieshave been done of the directeffects of this strategyon disorderor fearof crime.The best evidence concerningthe effectivenessof rapidresponsecomes fromtwo studiesconducted in the late 1970s (KansasCity Police Department 1977; Spelman and Brown1981).Evidencefromfive cities examinedin these two studiesconsistently showsthatmostcrimes(about75 percentat the time of the studies)arediscovered some time afterthey have been committed.Accordingly, offendersin such cases havehadplentyof time to escape. Forthe minority of crimesin whichthe offender and the victimhave some type of contact,citizen delayin callingthe police blunts whatevereffect a marginal in responsetime mightprovide. improvement Generally appliedfollow-up investigations of crimes in No studiesto date examinethe direct impactof generalizedimprovements of crime. or fear Nonetheless,it police investigation techniqueson crime,disorder, has been assumed that an increase in the likelihood of a crime'sbeing solved effect. Researchsugthrougharrestwould lead to a deterrenceor incapacitation gests, however,that the single most importantfactorleadingto arrestis the presence of witnessesor physicalevidence (Greenwood, Chaiken,andPetersilia1977; Eck 1983)-factors thatarenot underthe controlof the police and aredifficultto in investigative manipulate throughimprovements approaches. Generally applied intensive enforcementand arrests Toughlawenforcementstrategieshavelong been a stapleof police crime-fighting. We reviewedthree broadareasof intensiveenforcementwithinthe standard model:disorderpolicing,generalizedfield interrogations andtrafficenforcement, and mandatory and preferredarrestpoliciesin domesticviolence. Disorderpolicing.The modelof intensiveenforcementappliedbroadlyto inciwindows vilitiesandothertypesof disorderhasbeen describedrecentlyas "broken "zero or tolerance and Sousa Coles and 2001) 1996; Kelling policing"(Kelling 2001). policing" (Bowling1999;Cordner1998;Dennis andMallon1998;Manning While the common perceptionis that enforcement strategies(primarily arrest)

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REDUCING CRIME, DISORDER, AND FEAR

51

in appliedbroadlyagainstoffenderscommittingminoroffenseslead to reductions seriouscrime, researchdoes not providestrongsupportfor this proposition.For example, studies in seven cities that were summarizedby Skogan(1990, 1992) found no evidence that intensiveenforcementreduced disorder,which went up despite the specialprojectsthat were being evaluated.More recent claimsof the effects of disorderpolicingbased on crime declines in New YorkCity have also been strongly challengedbecausethey areconfoundedwitheitherotherorganizationalchangesin New York(notablyCompstat; see Eck and Maguire2000), other changessuch as the crackepidemic(see Bowling1999;Blumstein1995),or more generalcrimetrends(Eck and Maguire2000). One correlational studyby Kelling and Sousa(2001) founda directlinkbetween misdemeanor arrestsand moreserious crime in New York,althoughlimitationsin the data availableraisequestions aboutthe validityof these conclusions. Limitedevidencesupand trafficenforcement. Generalizedfield interrogations in reducingspecific types of crime, ports the effectivenessof field interrogations though the numberof studies availableis smalland the findingsare mixed.One strong quasi-experimental study (Boydstun 1975) found that disorder crime decreasedwhen field interrogations were introducedin a police district.Whitaker et al. (1985) reportsimilarfindingsin a correlational studyof crimeandthe police in sixtyneighborhoods New in Tampa,Florida; andRochester, St. Louis,Missouri; York.Researchershave also investigatedthe effects of field interrogationsby examiningvariationsin the intensity of traffic enforcement. Two correlational studiessuggestthatsuchinterventions do reducespecifictypesof crime (Sampson andCohen 1988;J.Q. WilsonandBoland1979).However,the causallinkbetween enforcementandcrimein these studiesis uncertain.In a moredirectinvestigation of the relationship between trafficstops andcrime,Weissand Freels (1996) coma treatment in which trafficstopswere increasedwith a matchedconarea pared trolarea.Theyfoundno significant crimeforthe twoareas. differencesin reported arrestin misdeMandatoryarrest policiesfor domesticviolence. Mandatory meanorcases of domesticviolence is now requiredby law in manystates.Consistentwiththe standard modelof policing,these lawsapplyto allcitiesin a state,in all areas of the cities, for all kindsof offendersand situations.Researchand public interestin mandatory arrestpolicies for domesticviolence was encouragedby an importantexperimentalstudy in Minneapolis,Minnesota (Shermanand Berk 1984a, 1984b),which foundreductionsin repeatoffendingamongoffenderswho were arrestedas opposed to those who were counseled or separatedfrom their partners.This studyled to a series of replications supportedby the NationalInstitute of Justice.These experimentsfound deterrenteffects of arrestin two cities and no effect of arrest in three other cities (Berk et al. 1992; Dunford 1990; Dunford, Huizinga,and Elliot 1990; Hirschel and Hutchinson 1992; Pate and Hamilton1992;Shermanet al. 1991),suggestingthatthe effects of arrestwillvary by city, neighborhood,and offender characteristics(see also Sherman 1992; Maxwell,Garner,and Fagan2001, 2002).

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

52

THE ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY

on the 2: Overthe pasttwodecades, investment therehasbeena major Proposition partof the police and the publicin community policing.Becausecommunity so manydifferent cannot tactics,its effectas a generalstrategy policinginvolves forthe posibe evaluated. the evidencedoesnotprovide Overall, support strong tion thatcommunity on crimeor disorder. policingapproaches impactstrongly tacticsto reduce is foundforthe ability of community Stronger support policing fearof crime. Police practices associatedwith communitypolicing have been particularly broad, and the strategiesassociatedwith communitypolicing have sometimes element changedovertime. Foot patrol,forexample,wasconsideredanimportant of communitypolicingin the 1980s but has not been a core componentof more recent communitypolicingprograms.Consequently, it is often difficultto determine if researchers in different agenciesat different studyingcommunitypolicing times are studying the same phenomena. One recent correlationalstudy that

The research available suggests that when the police partner more generally with the public, levels of citizenfear will decline.

attemptsto assess the overallimpactof federalgovernmentinvestmentfor communitypolicing found a positive crime control effect of "hiringand innovative 2002);however,a recentreviewof (Zhao,Scheider,andThurman grantprograms" this work by the GeneralAccountingOffice (2003) has raised strong questions the validityof the findings. regarding Studiesdo not supportthe view thatcommunitymeetings(Wycoffand Skogan watch (Rosenbaum1989), storefrontoffices (Skogan1990; 1993), neighborhood Uchida, Forst, and Annan 1992), or newsletters(Pate and Annan 1989) reduce crime, althoughSkoganand Hartnett(1995) foundthat such tacticsreducecommunityperceptionsof disorder.Door-to-doorvisits have been found to reduce both crime (see Sherman1997) and disorder(Skogan1992). Simplyproviding information aboutcrime to the public,however,does not have crime prevention benefits (Sherman1997).

As noted above, foot patrol was an important component of early community policing efforts. An early uncontrolled evaluation of foot patrol in Flint, Michigan, concluded that foot patrol reduced reported crime (Trojanowicz 1986). However, Bowers and Hirsch (1987) found no discernable reduction in crime or disorder due

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REDUCING CRIME, DISORDER, AND FEAR

53

to foot patrols in Boston. A more rigorous evaluation of foot patrol in Newark also found that it did not reduce criminal victimizations (Police Foundation 1981). Nonetheless, the same study found that foot patrol reduced residents' fear of crime. Additional evidence shows that community policing lowers the community's level of fear when programs are focused on increasing community-police interaction. A series of quasi-experimental studies demonstrate that policing strategies characterized by more direct involvement of police and citizens, such as citizen contract patrol, police community stations, and coordinated community policing, have a negative effect on fear of crime among individuals and on individual level of concern about crime in the neighborhood (Brown and Wycoff 1987; Pate and Skogan 1985; Wycoff and Skogan 1986). An aspect of community policing that has only recently received systematic research attention concerns the influences of police officer behavior toward citizens. Citizen noncompliance with requests from police officers can be considered a form of disorder. Does officer demeanor influence citizen compliance? Based on systematic observations of police-citizen encounters in three cities, researchers found that when officers were disrespectful toward citizens, citizens were less likely to comply with their requests (Mastrofski, Snipes, and Supina 1996; McCluskey, Mastrofski, and Parks 1999). Proposition3: There has been increasinginterest over the past two decades in police practices that targetvery specific types of criminalsand crime places. In particular,policing crime hot spots has become a common police strategyfor addressing public safety problems. While only weak evidence suggests the effectiveness of targetingspecific types of offenders, a strong body of evidence suggests that taking a focused geographic approach to crime problems can increase policing effectiveness in reducing crime and disorder. While the standard model of policing suggests that police activities should be spread in a highly uniform pattern across urban communities and applied uniformly across the individuals subject to police attention, a growing number of police practices focus on allocating police resources in a focused way. We reviewed research in three specific areas: (1) police crackdowns, (2) hot-spots policing, and (3) focus on repeat offenders.

Police crackdowns

There is a long history of police crackdowns that target particularlytroublesome locations or problems. Such tactics can be distinguished from more recent hotspots policing approaches (described below) in that they are temporary concentrations of police resources that are not widely applied. Reviewing eighteen case studies, Sherman (1990) found strong evidence that crackdowns produce short-term deterrent effects, though research is not uniformly in support of this proposition (see, e.g., Annan and Skogan 1993; Barber 1969; Kleiman 1988). Sherman (1990)

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

54

THE ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY

of crimeto nearby alsoreportsthatcrackdowns did not leadto spatialdisplacement areasin the majority of studieshe reviewed. Hot-spots policing Althoughthere is a long historyof effortsto focus police patrols(Gay,Schell, and Schack1977;0. W Wilson1967),the emergenceof whatis often termedhotinnospotspolicingis generallytracedto theoretical,empirical,andtechnological vationsin the 1980s and 1990s (Weisburd and Braga2003; Braga2001; Sherman andWeisburd1995). A seriesof randomized field trialsshowsthatpolicingthatis in crimeanddisorder(see focusedon hot spotscan resultin meaningful reductions 2001). Braga and The firstof these, the Minneapolis Hot SpotsPatrolExperiment(Sherman Weisburd1995), used computerizedmappingof crime calls to identify 110 hot spots of roughlystreet-blocklength. Police patrolwas doubledon averagefor the sitesovera ten-monthperiod.The studyfoundthatthe experimental experimental as comparedwith the controlhot spotsexperiencedstatistically significantreducthe tionsin crimecallsandobserveddisorder. In anotherrandomized experiment, KansasCityCrackHouse RaidsExperiment(Shermanand Rogan1995a),crackdowns on drug locationswere also found to lead to significantrelativeimprovementsin the experimental the effects (measured sites, although by citizencallsand offense reports)were modest and decayedin a shortperiod. In yet anotherrandomizedtrial,however,Eck andWartell(1996) foundthatif the raidswere immecrimepreventionbenefitscould diatelyfollowedby police contactswithlandlords, be reinforcedand would be sustainedfor long periods. More generalcrime and thattake a more disordereffects are alsoreportedin two randomized experiments to tailored, problem-orientedapproach hot-spots policing (Braga et al. 1999; Weisburdand Green 1995a,because of their use of problem-solving approaches, studiesprowe discussthem in more detailin the nextsection). Nonexperimental and vide similarfindings(see Hope 1994;Sherman Rogan1995b). has strongempiricalsupThe effectivenessof the hot-spotspolicingapproach port. Such approacheswould be much less useful, however,if they simplydisis of crimedisplacement placedcrimeto othernearbyplaces.While measurement a number and Green 1995b), complexand a matterof debate (see, e.g., Weisburd of the studies reportedabove examinedimmediategeographicdisplacement.In and Green 1995a), the JerseyCity Drug MarketAnalysisExperiment(Weisburd for example,displacementwithintwo blockareasaroundeach hot spot was measured. No significantdisplacementof crime or disordercalls was found. Imporcalls and public-morals found that drug-related tantly,however,the investigators benecontrol crime of "diffusion in This declined the areas. actually displacement fits" (Clarkeand Weisburd1994) was also reportedin the New JerseyViolent Crime Places experiment (Braga et al. 1999), the Beat Health study (Green andRogan Mazerolle andRoehl 1998),andthe Kansas CityGunProject(Sherman of crimewasreported,andsome 1995b).In each of these studies,no displacement in the surrounding areaswasfound.OnlyHope (1994)reportsdirect improvement

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REDUCING CRIME, DISORDER, AND FEAR

55

displacement of crime, although this occurred only in the area immediate to the treated locations and the displacement effect was much smaller overall than the crime prevention effect.

Focusing on repeat offenders

Two randomized trials suggest that covert investigation of high-risk, previously convicted offenders has a high yield in arrests and incarceration per officer per hour, relative to other investments of police resources (Abrahamse and Ebener 1991; Martin and Sherman 1986). It is important to note, however, that these evaluations examined the apprehension effectiveness of repeat-offender programs not the direct effects of such policies on crime. However, a recent study-The Boston Ceasefire Project (Kennedy, Braga, and Piehl 1996)-which used a multiagency and problem-oriented approach (referred to as a "pullinglevers" strategy), found a reduction in gang-related killings as well as declines in other gun-related events when focusing on youth gangs (Kennedy et al. 2001). Another method for identifying and apprehending repeat offenders is "antifencing,"or property sting, operations, where police pose as receivers of stolen property and then arrest offenders who sell them stolen items (see Weiner, Chelst, and Hart 1984; Pennell 1979; Criminal Conspiracies Division 1979). Although a number of evaluations were conducted of this practice, most employed weak research designs, thus making it difficult to determine if such sting operations reduce crime. There seems to be a consensus that older and criminally active offenders are more likely to be apprehended using these tactics as compared with more traditional law enforcement practices, but they have not been shown to have an impact on crime (Langworthy 1989; Raub 1984; Weiner, Stephens, and Besachuk 1983). Proposition4: Problem-oriented policing emerged in the 1990s as a central police strategy for solving crime and disorder problems. There is a growing body of research evidence that problem-oriented policing is an effective approach for reducing crime, disorder,and fear. Research is consistently supportive of the capability of problem solving to reduce crime and disorder. A number of quasi-experiments going back to the mid1980s consistently demonstrates that problem solving can reduce fear of crime (Cordner 1986), violent and property crime (Eck and Spelman 1987), firearmrelated youth homicide (Kennedy et al. 2001), and various forms of disorder, including prostitution and drug dealing (Capowich and Roehl 1994; Eck and Spelman 1987; Hope 1994). For example, a quasi-experiment in Jersey City, New Jersey, public housing complexes (Green Mazerolle et al. 2000) found that police problem-solving activities caused measurable declines in reported violent and property crime, although the results varied across the six housing complexes studied. In another example, Clarke and Goldstein (2002) report a reduction in thefts of appliances from new home construction sites following careful analysis of this

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

56

THE ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY

Police Departmentand the implementaproblemby the Charlotte-Mecklenburg tion of changesin buildingpracticesby constructionfirms. Two experimentalevaluationsof applications of problem solvingin hot spots trialwith In a randomized suggestits effectivenessin reducingcrimeanddisorder.' JerseyCityviolentcrime hot spots, Bragaet al. (1999) reportreductionsin propertyandviolentcrimein the treatmentlocations.Whilethis studytested problemsolving approaches,it is importantto note that focused police attention was it is difficultto distinguish locations.Accordingly, broughtonlyto the experimental between the effects of bringingfocused attentionto hot spots and that of such focused efforts being developed using a problem-oriented approach.The Jersey Market Green and 1995a) provides (Weisburd City Drug AnalysisExperiment more direct supportfor the added benefit of the applicationof problem-solving approachesin hot-spots policing. In that study, a similarnumber of narcotics

The effectivenessof the hot-spots policing approach has strong empirical support.

detectiveswere assignedto treatmentandcontrolhot spots.Weisburdand Green enforcement arrest-oriented (1995a)comparedthe effectivenessof unsystematic, based on ad hoc target selection (the control group) with a treatmentstrategy of assigneddrughot spots,followedby site-specificenforcement involving analysis and collaboration with landlordsand local governmentregulatory agencies, and for up to a week followingthe interand maintenance concludingwith monitoring vention. Comparedwith the controldrughot spots, the treatmentdrughot spots faredbetter with regardto disorderand disorder-related crimes. Evidenceof the effectivenessof situational andopportunity-blocking strategies, while not necessarily police based,providesindirectsupportfor the effectiveness of problemsolvingin reducingcrimeanddisorder. Problem-oriented policinghas been linkedto routineactivitytheory,rational choice perspectives,and situational crimeprevention(Clarke1992a, 1992b;Eck and Spelman1987). Recent reviews of preventionprogramsdesigned to block crime and disorderopportunitiesin in targetcrimeanddissmallplacesfindthatmostof the studiesreportreductions order events (Eck 2002; Poyner 1981; Weisburd1997). Furthermore,many of these efforts were the result of police problem-solving strategies.We note that of the studies weak reviewed designs (Clarke 1997; many employed relatively Weisburd1997; Eck 2002).

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REDUCING AND FEAR CRIME,DISORDER, TABLE 1 SYNTHESIS OF FINDINGS ON POLICE EFFECTIVENESS RESEARCH Police Strategies That ... Apply a diverse arrayof approaches, including law enforcement sanctions. Are Unfocused Inconsistent or weak evidence of effectiveness Impersonalcommunity policing, for example, newsletters Weak to moderate evidence of effectiveness Personalcontacts in community policing Respectful police-citizen contacts Improving legitimacyof police Foot patrols (fear reduction) Inconsistent or weak evidence of effectiveness Adding more police General patrol Rapid response Follow-up investigations Undifferentiated arrest for domestic violence Are Focused

57

Moderate evidence of effectiveness Problem-orientedpolicing Strong evidence of effectiveness Problem solving in hot spots

Rely almost exclusively on law enforcement sanctions

Inconsistent or weak evidence of effectiveness Repeat offender investigations Moderate to strong evidence of effectiveness Focused intensive enforcement Hot-spots patrols

Discussion

We began our article with a series of questions about what we have learned from research on police effectiveness over the last three decades. In Table 1, we summarize our overall findings using the typology of police practices that we presented earlier. One of the most striking observations in our review is the relatively weak evidence there is in support of the standard model of policing--defined as low on both of our dimensions of innovation. While this approach remains in many police agencies the dominant model for combating crime and disorder, we find little empirical evidence for the position that generally applied tactics that are based primarily on the law enforcement powers of the police are effective. Whether the strategy examined was generalized preventive patrol, efforts to reduce response time to citizen calls, increases in numbers of police officers, or the introduction of generalized follow-up investigations or undifferentiated intensive enforcement activities, studies fail to show consistent or meaningful crime or disorder prevention benefits or evidence of reductions in citizen fear of crime. Of course, a conclusion that there is not sufficient research evidence to support a policy does not necessarily mean that the policy is not effective. Given the continued importance of the standard model in American policing, it is surprising that so little substantive research has been conducted on many of its key components. Pre-

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

58

THE ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY

ventive patrol,for example,remainsa staple of Americanpolice tactics.Yet our knowledgeaboutpreventivepatrolis basedonjust a few studiesthataremorethan two decades old and that have been the subjectof substantial criticism.Even in cases where a largernumberof studiesare available, like thatof the effects of addoutcomesgenering morepolice, the nonexperimental designsused forevaluating ally makeit difficultto drawstrongconclusions. This raisesa more generalquestionaboutour abilityto come to strongconclusions regardingcentralcomponentsof the standardmodel of policing.With the arrestfor domestic violence, the evidence we review is exceptionof mandatory drawnfromnonexperimental confounded These studiesaregenerally evaluations. in one way or anotherby threatsto the validityof the findingspresented.Indeed, manyof the studies in such areasas the effects of police hiringare correlational studiesusingexistingdatafromofficialsources.Someeconomistshavearguedthat the use of econometricstatistical designscan providea level of confidencethatis almostas high as randomized experiments(Heckmanand Smith 1995).We think thatthisconfidenceis not warranted becauseof the lack in police studiesprimarily of very strongtheoreticalmodels for understanding policing outcomes and the of officialpolice data.But about and that can be raised questions validity reliability whatdoes thismeanforourabilityto come to strongconclusionsaboutpolicepractices thataredifficultto evaluateusingrandomized the designs,suchas increasing numbersof police or decreasingresponsetime? A simpleanswerto this questionis to arguethatourtaskis to improveourmethods anddataovertimewiththe goalof improving of ourfindings.In this the validity advancemethodsin some to recent tried has research on regard, police strength to Levitt on see conclusions 1997). We thinkthis ways likely improve prior (e.g., is for not conclusions to approach important coming strong only aboutthe effectivenessof the standard modelof policingbut alsoaboutrecentpolice innovation. we thinkexperimental methodscan be appliedmuch more But, more generally, in broadly this area,as in other areasof policing. For example,we see no reason why the additionof police officers in federal governmentprogramsthat offer financialassistanceto localpolice agenciescould not be implementedexperimenin such cases, methodsmightbe controversial tally.Whilethe use of experimental the fact that we do not know whether marginalincreasesin police strengthare effective at reducing crime, disorder, or fear suggests the importance and legitimacyof such methods. modelsof Whilewe havelittleevidenceindicating the effectivenessof standard policing in reducing,crime, disorder,or fear of crime, the strongestevidence of police effectivenessin our reviewis found in the cell of our table that represents focused policingefforts.Studiesthat focusedpolice resourceson crime hot spots providethe strongestcollectiveevidence of police effectivenessthat is now available.A series of randomized studiessuggeststhathot-spotspolicing experimental is effectivein reducingcrimeand disorderandcan achievethese reductionswithout significantdisplacementof crime controlbenefits. Indeed, the researchevidence suggeststhat the diffusionof crime control benefits to areassurrounding treatedhot spots is strongerthan anydisplacementoutcome.

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REDUCING CRIME, DISORDER, AND FEAR

59

The two remainingcells of the table indicatethe promiseof new directionsfor once morethe tendency policingin the United States;however,they alsoillustrate for widelyadoptedpolice practicesto escape systematicor high-quality investigation. Communitypolicing has become one of the most widely implemented in American approaches policingandhas receivedunprecedentedfederalgovernment supportin the creationof the Office of CommunityOrientedPolicingServices andits grantprogram forpolice agencies.Yetin reviewing existingstudies,we could find no consistentresearchagendathatwouldallowus to assesswith strong confidence the effectiveness of communitypolicing. Given the importanceof communitypolicing,we were surprisedthat more systematicstudywas not available.Asin the caseof manycomponentsof the standard model,researchdesignsof the studies we examined were often weak, and we found no randomized experimentsevaluating communitypolicingapproaches. Whilethe evidenceavailable does not allowfordefinitiveconclusionsregarding we community policingstrategies, do not findconsistentevidencethatcommunity it is implemented without problem-orientedpolicing) affects (when policing either crime or disorder.However,the researchavailablesuggeststhatwhen the police partnermore generallywith the public, levels of citizen fear will decline. Moreover,growingevidence demonstratesthat when the police are able to gain widerlegitimacyamongcitizensand offenders,the likelihoodof offendingwill be reduced. There is greaterand more consistentevidence that focused strategiesdrawing on a wide array of non-law-enforcement tacticscan be effectivein reducingcrime anddisorder. These strategies,foundin the upperrightof the table,maybe classed more generally withinthe model of problem-oriented policing.While manyproblem-oriented policing programsemploy traditionallaw enforcement practices, The researchavailmanyalsodrawon a widergroupof strategiesandapproaches. able suggeststhatsuch tools can be effectivewhen they arecombinedwith a tactical philosophythat emphasizesthe tailoringof policingpracticesto the specific of the problemsor places that are the focus of intervention. characteristics While the primary evidencein supportof the effectivenessof problem-oriented policing is nonexperimental, initialexperimental studiesin this areaconfirmthe effectiveness of problem-solving and suggestthatthe expansionof the toolbox approaches of policingpracticesin combination with greaterfocus can increaseeffectiveness overall.

Conclusions

Reviewing the broad arrayof research on police effectiveness in reducing or tacandfearratherthanfocusingin on anyparticular crime,disorder, approach tic providesan opportunity to considerpolicingresearchin contextand to assess whatthe cumulative bodyof knowledgewe have suggestsforpolicingpracticesin the comingdecades.Perhapsthe most disturbing conclusionof our reviewis that of of the core of American knowledge many policingremainsuncertain. practices

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

60

THE ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY

the United Stateshavenot been Manytacticsthatare appliedbroadlythroughout the subjectof systematic police researchnor havethey been examinedin the context of researchdesigns that allow practitionersor policy makersto draw very strongconclusions.We think this fact is particularly troublingwhen considering the vastpublicexpenditures of their effecon such strategiesandthe implications more tivenessforpublicsafety.American become must research systematic police and more experimental if it is to providesolid answersto importantquestionsof practiceand policy. But what shouldthe police do given existingknowledgeaboutpolice effectiveness? Police practicehas been centered on standard strategiesthat relyprimarily on the coercivepowers of the police. There is little evidence to suggest that this standard model of policingwill lead to communitiesthat feel and are safer.While forotherreasons,thereis not consispolice agenciesmaysupportsuchapproaches tent scientific evidence that such tactics lead to crime or disordercontrol or to reductionsin fear.In contrast,researchevidence does supportcontinuedinvestment in police innovations thatcall for greaterfocus andtailoringof police efforts and for the expansionof the toolboxof policingbeyondsimple law enforcement. The strongestevidenceis in regardto focusandsurrounds suchtacticsas hot-spots et al. Police now such on policing. agencies approaches(Weisburd routinelyrely reliance such that is Weisburd and Lum and the research 2001; 2001), suggests warranted. Shouldpolice agenciescontinueto encouragecommunity-and problem-orientedpolicing?Our reviewsuggeststhat communitypolicing (when it is not combinedwithproblem-oriented will makecitizensfeel saferbut approaches) will not necessarilyimpact upon crime and disorder.In contrast,what is known about the effects of problem-oriented policingsuggestsits promisefor reducing and fear. crime, disorder,

Note

1. An earlyexperimentalhot-spots study that tested problem solvingat high crime-calladdresses did not show a significantcrime or disorder reduction impact (Buerger 1994; Sherman 1990). However, Buerger, Cohn, and Petrosino (1995) argue that there was insufficientdosage acrossstudy sites to produce any meaningful treatment impact.

References

Abrahamse, Allan F, and Patricia A. Ebener. 1991. An experimental evaluation of the Phoenix repeat offender program.Justice Quarterly 8 (2): 141-68. Annan, Sampson 0., and Wesley G. Skogan. 1993. Drug enforcementin public housing: Signs of success in Denver. Washington,DC: Police Foundation. Barber,R. N. 1969. Prostitutionand the increasingnumberof convictionsfor rapein Queensland.Australian and New ZealandJournal of Criminology2 (3): 169-74. Oxford UniversityPress. Bayley,David H. 1994. Policefor thefuture. New York: Berk, RichardA., Alec Campbell, Ruth Klap, and Bruce Western. 1992. Bayesiananalysisof the Colorado Springs spouse abuse experiment.Journalof Criminal Law and Criminology83 (1): 170-200. Blumstein, Alfred. 1995. Youth violence, guns and the illicit-drugindustry.Journal of Criminal Law and Criminality 86:10-36.

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REDUCING CRIME, DISORDER, AND FEAR

61

Boruch, Robert, Timothy Victor,and Joe Cecil. 2000. Resolving ethical and legal problems in randomized studies. Crime and Delinquency 46 (3): 330-53. Bowers,William,andJon H. Hirsch. 1987. The impactof foot patrolstaffingon crime and disorderin Boston: An unmet promise. AmericanJournal of Policing 6 (1): 17-44. Bowling, Benjamin. 1999. The rise and fall of New Yorkmurder.BritishJournal of Criminology39 (4): 53154. Boydstun,John. 1975. The San Diegofield interrogationexperiment.Washington,DC: Police Foundation. Braga,Anthony A. 2001. The effects of hot spots policing on crime. The Annals of American Political and Social Science 578:104-25. Braga,AnthonyA., DavidWeisburd,Elin J. Waring,LorraineGreen Mazerolle,WilliamSpelman,and Francis Gajewski.1999. Problem-orientedpolicing in violent crime/places:A randomizedcontrolled experiment. Criminology37 (3): 541-80. Bratton,WilliamJ. 1998. Crime is down in New YorkCity:Blame the police. In Zerotolerance:Policingafree society, edited by WilliamJ. Brattonand Norman Dennis. London:Institute of Economic AffairsHeath and Welfare Unit. Brown, Lee P., and MaryAnn Wycoff. 1987. Policing Houston: Reducing fear and improvingservice. Crime and Delinquency 33:71-89. Buerger,Michael E. 1994. The problemsof problem-solving:Resistance,interdependencies, and conflicting interests. AmericanJournal of Police 13 (3): 1-36. Buerger, Michael E., Ellen G. Cohn, and Anthony J. Petrosino. 1995. Defining the "hot spots of crime": Operationalizingtheoretical concepts for field research. In Crime and place, edited by John Eck and David Weisburd. Monsey, NY:CriminalJustice Press. Campbell, Donald T., and Robert Boruch. 1975. Makingthe case for randomizedassignmentto treatments evaluationsin compensatoryeducaby consideringthe alternatives:Sixwaysin which quasi-experimental tion tend to underestimateeffects. In Evaluationand experiment:Somecritical issues in assessingsocial programs, edited by Carl A. Bennett and ArthurA. Lumsdaine. New York:Academic Press. Capowich, George E., and Janice A. Roehl. 1994. Problem-orientedpolicing: Actions and effectiveness in San Diego. In Communitypolicing: Testingthe promises, edited by Dennis P. Rosenbaum. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Chamlin, Mitchell B., and Robert Langworthy.1996. The police, crime, and economic theory:A replication and extension. AmericanJournal of CriminalJustice 20 (2): 165-82. Clarke, RonaldV. 1992a. Situationalcrime prevention:Theory and practice. BritishJournalof Criminology 20:136-47. 1992b. Situationalcrime prevention: Successfulcase studies. Albany,NY:Harrowand Heston. Harrowand Heston. . 1997. Situationalcrimeprevention:Successfulcase studies. 92nd ed. New York: Clarke, RonaldV., and Herman Goldstein. 2002. Reducing theft at constructionsites: Lessons from a problem-oriented project. In Analysisfor crime prevention, edited by Nick Tilley. Monsey, NY:CriminalJustice Press. Clarke, Ronald V., and David Weisburd. 1994. Diffusion of crime control benefits: Observationson the reverse of displacement. Crime Prevention Studies 2:165-84. Cook, Thomas, and Donald Campbell. 1979. Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues. Chicago: Rand McNally. Cordner, Gary 1986. Fear of crime and the police: An evaluationof a fear-reductionstrategy.Journal of W. Police Science and Administration 14 (3): 223-33. . 1998. Problem-orientedpolicing vs. zero-tolerance. In Problem-orientedpolicing, edited by Tara O'Connor Shelly and Anne C. Grant.Washington,DC: Police Executive Research Forum. Cornish, Derek B., and RonaldV.Clarke. 1972. Homeoffice researchstudies, number15: Thecontrolledtrial in institutional research: Paradigm or pitfallfor penal evaluators? London: Her Majesty'sStationery Office. CriminalConspiraciesDivision. 1979. What happened:An examinationof recently terminatedanti-fencing operations-A special report to the administrator Washington, DC: Law Enforcement Assistance Administration,U.S. Department of Justice. Dahmann, Judith S. 1975. Examinationof Police Patrol Effectiveness.McLean, VA:Mitre Corporation.

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

62

THE ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY

Dennis, Norman, and Ray Mallon. 1998. Confident policing in Hartlepool.In Zero tolerance:Policingafree society, edited by WilliamJ. Brattonand Norman Dennis. London:Institute of Economic AffairsHeath and Welfare Unit. Dunford, FranklinW 1990. System-initiatedwarrantsfor suspects of misdemeanordomestic assault:A pilot study.Justice Quarterly 7 (1): 631-54. Dunford, FranklinW, David Huizinga, and Delbert S. Elliot. 1990. Role of arrest in domestic assault:The Omaha police experiment. Criminology28 (2): 183-206. Eck, John E. 1983. Solving crime:A study of the investigation of burglary and robbery.Washington, DC: Police Executive Research Forum. . 2002. Preventing crime at places. In Evidence-based crime prevention, edited by Lawrence W. Sherman, David Farrington, Brandon Welsh, and Doris Layton MacKenzie, 241-94. New York: Routledge. Eck, John E., and EdwardMaguire.2000. Have changes in policing reduced violent crime?An assessmentof the evidence. In The crime drop in America, edited by Alfred Blumstein and Joel Wallman.New York: Cambridge UniversityPress. Eck, John E., and Dennis Rosenbaum. 1994. The new police order: Effectiveness, equity and efficiency in community policing. In Community policing: Testingthe promises, edited by Dennis P. Rosenbaum. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Eck, John E., and William Spelman. 1987. Problemsolving: Problemoriented policing in Newport news. Washington,DC: Police Executive Research Forum. and drug dealing by improvingplace management:A Eck, John E., and JulieWartell. 1996. Reducingcrinme randomizedexperiment:Report to the San Diego Police Department. Washington,DC: Crime Control Institute. Farrington,David. 1983. Randomized studies in criminaljustice. Crime and justice: An annual review of research, vol. 4, edited by MichaelTonryand Norval Morris.Chicago: Universityof Chicago Press. Feder, Lynette, and Robert Boruch.2000. The need for randomizedexperimentaldesigns in criminaljustice settings. Crime and Delinquency 46 (3): 291-94. Gay,William G., Theodore H. Schell, and Stephen Schack. 1977. Prescriptivepackage: Improving patrol productivity, volume I routine patrol. Washington, DC: Office of Technology Transfer,Law Enforcement Assistance Administration. 2001 Evaluationofthe effects GeneralAccountingOffice. 2003. TechnicalassessmentofZhao and Thurman's of COPS grants on crime. Retrieved September 3, 2003, from http://www.gao.gov/new.items/ d03867r.pdf. Goldstein, Herman. 1979. Improving policing: A problem oriented approach. Crime and Delinquency 24:236-58. . 1987. Towardcommunity-orientedpolicing:Potential,basic requirementsand thresholdquestions. Crime and Delinquency 33 (1): 6-30. . 1990. Problem-orientedpolicing. New York:McGraw-Hill. Gottfredson,Michael,and TravisHirschi. 1990.A generaltheoryof crime. Palo Alto, CA:StanfordUniversity Press. eds. 1988. Communitypolicing: Rhetoricor reality. New York: Greene, JackR., and Stephen D. Mastrofski, Praeger. Green Mazerolle,Lorraine,JustinReady,WilliamTerrill,and Elin Waring.2000. Problem-orientedpolicing in public housing:The Jersey City evaluation. Justice Quarterly 17 (1): 129-58. Green Mazerolle,Lorraine,andJan Roehl. 1998. Civil remediesand crimeprevention. Munsey,NJ:Criminal Justice Press. Greenwood, Peter W, JanChaiken,and JoanPetersilia.1977. Thecriminalinvestigationprocess. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath. Heckman, James, and JeffreyA. Smith. 1995. Assessingthe case for social experimentation.Journalof Economic Perspectives9 (2): 85-110. Hirschel, David J., and Ira W Hutchinson. 1992. Female spouse abuse and the police response:The Charlotte, North Carolinaexperiment.Journalof Criminal Law and Criminology83 (1): 73-119.

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REDUCING CRIME, DISORDER, AND FEAR

63

Hope, Tim. 1994. Problem-orientedpolicing and drug marketlocations:Three case studies. In Crime prevention studies, vol. 2, edited by Ronald V Clarke. Monsey, NY:CriminalJustice Press. Kansas City Police Department. 1977. Response time analysis. Kansas City, MO: Kansas City Police Department. Kelling,George, and Catherine M. Coles. 1996. Fixingbrokenwindows:Restoringorderand reducingcrime in our communities. New York:Free Press. Kelling, G., and W. H. Sousa Jr.2001. Do police matter? An analysis of the impact of New YorkCity's Police ReformsCivic Report 22. New York:ManhattanInstitute for Policy Research. Kelling,George, TonyPate, Duane Dieckman, and Charles Brown. 1974. The KansasCity preventivepatrol experiment:Technicalreport. Washington,DC: Police Foundation. Kennedy,David M., AnthonyA. Braga,and Anne MorrisonPiehl. 1996. Youthgun violence in Boston: Gun markets,serious youth offenders,and a use reductionstrategy. Boston, MA:John F Kennedy School of Government, HarvardUniversity. Kennedy, David M., AnthonyA. Braga,Anne MorrisonPiehl, and Elin J. Waring.2001. Reducinggun violence: TheBoston Gun Project's OperationCeasefire.Washington,DC: U.S. NationalInstituteofJustice. The effects of intensive enforcement on retailheroin dealing. In StreetKleiman,Mark.1988. Crackdowns: level drug enforcement:Examining the issues, edited by Marcia Chaiken. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice. Kunz, Regina, and AndrewOxman. 1998. The unpredictability paradox:Review of empiricalcomparisonsof randomized and non-randomizedclinical trials.British MedicalJournal 317:1185-90. Langworthy,Robert H. 1989. Do stings control crime? An evaluationof a police fencing operation.Justice Quarterly 6 (1): 27-45. Larson, Richard C., and Michael F. Cahn. 1985. Synthesizingand extending the results of police patrols. Washington, DC: U.S. Government PrintingOffice. Levitt, Steven D. 1997. Using election cycles in police hiringto estimate the effect of police on crime.American Economic Review 87 (3): 270-90. Manning,Peter K.2001. Theorizingpolicing:The dramaand mythof crime controlin the NYPD. Theoretical Criminology5 (3): 315-44. Manski,CharlesF 2003. Credible researchpracticesto informdruglaw enforcement. Criminologyand Public Policy 2 (3): 543-56. Martin, Susan E., and Lawrence W. Sherman. 1986. Selective apprehension:A police strategy for repeat offenders. Criminology24 (1): 155-73. Martinson,Robert. 1974. Whatworks?Questions and answersaboutprisonreform.PublicInterest35:22-54. Marvell, Thomas B., and Carlisle E. Moody. 1996. Specification problems, police levels, and crime rates. Criminology 34 (4): 609-46. Mastrofski,Stephen D., Jeffrey B. Snipes, and Anne E. Supina. 1996. Compliance on demand: The public response to specific police requests.Journalof Researchin Crime and Delinquency 3:269-305. Maxwell,ChristopherD., Joel D. Garner,and JeffreyA. Fagan.2001. Theeffectsofarrest on intimatepartner violence: New evidence from the spouse assault replication program, research in Brief NCJ 188199. Washington,DC: National Institute of Justice. - . 2002. The preventive effects of arrest on intimate partner violence: Research, policy, and theory. Criminologyand Public Policy 2 (1): 51-95. and Roger B. Parks.1999.To acquiesce or rebel:PredictingcitiMcCluskey,John D., Stephen D. Mastrofski, zen compliance with police requests. Police Quarterly 2:389-416. Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation, Inc. 1976. Critiques and commentaries on evaluationresearch activities-Russell Sage reports.Evaluation 3 (1-2): 115-38. Niskanen, William. 1994. Crime, police, and root causes. Policy Analysis 218. Washington, DC: Cato Institute. Pate, Anthony M., and SampsonO. Annan. 1989. The Baltimorecommunitypolicing experiment:Technical report. Washington,DC: Police Foundation. Pate, AnthonyM., and Edwin E. Hamilton. 1992. Formaland informaldeterrents to domestic violence: The Dade County spouse assaultexperiment.American Sociological Review 57:691-98.

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

64

THE ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY

Pate, Anthony M., and Wesley G. Skogan. 1985. Coordinatedcommunitypolicing: The Newark experience. Technicalreport. Washington,DC: Police Foundation. Pawson, Ray,and Nick Tilley. 1997. Realistic evaluation. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Pedhazur,ElazarJ. 1982. Multipleregressionin behavioral research:Explanationand prediction. New York: Hold, Rinehartand Winston. Pennell, Susan. 1979. Fencing activityand police strategy Police Chief (September): 71-75. Police Foundation. 1981. The Newarkfoot patrol experiment.Washington,DC: Police Foundation. Poyner,Barry.1981. Crime preventionand the environment-Street attacksin city centres. Police Research Bulletin 37:10-18. Press, S. James. 1971. Some effects of an increase in police manpowerin the 20th precinct of New YorkCity. New York:New YorkCity Rand Institute. Raub, RichardA. 1984. Effects of antifencing operations on encouragingcrime. CriminalJustice Review 9 (2): 78-83. Rosenbaum, Dennis. 1989. Community crime prevention:A review and synthesis of the literature.Justice Quarterly5 (3): 323-95. Sampson,RobertJ., and JacquelineCohen. 1988. Deterrent effects of the police on crime:A replicationand theoretical extension. Law and Society Review 22 (1): 163-89. Shadish, William R, Thomas Cook, and Donald Campbell. 2002. Experimentaland quasi-experimental designs. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Sherman, Lawrence W 1990. Police crackdowns:Initial and residual deterrence. In Crime and justice: A review of research,vol. 12, edited by Michael Tonryand Norval Morris.Chicago: Universityof Chicago Press. 1992. Policing domestic violence: Experimentsand dilemmas. New York:Free Press. 1997. Policing for prevention. In Preventingcrime:Whatworks, what doesn't,what'spromising-A reportto the attorneygeneralof the UnitedStates, edited by LawrenceW Sherman,Denise Gottfredson, Doris MacKenzie,John Eck, Peter Reuter,and ShawnBushway. Washington,DC: United States Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Sherman,LawrenceW., and RichardA. Berk. 1984a. Specificdeterrenteffects of arrestfor domestic assault Minneapolis.Washington,DC: National Institute of Justice. . 1984b. Specific deterrent effects of arrestfor domestic assault.AmericanSociologicalReview 49 (2): 261-72. Sherman,LawrenceW, andJohn E. Eck. 2002. Policingforprevention. In Evidencebased crimeprevention, edited by Lawrence W Sherman, David Farrington,and BrandonWelsh. New York:Routledge. Sherman, LawrenceW., David P. Farrington,BrandonC. Welsh, and Doris Layton MacKenzie. 2002. Evidence-based crime prevention. New York:Routledge. Sherman, Lawrence W., Denise Gottfredson, Doris Layton MacKenzie, John E. Eck, Peter Reuter, and Shawn Bushway.1997. Preventingcrime: What works, what doesn't, what'spromising-A report to the attorney general of the United States. Washington,DC: United States Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Sherman,LawrenceW, and Dennis P.Rogan. 1995a. Deterrent effects of police raidson crackhouses: A randomized, controlled, experiment.Justice Quarterly 12 (4): 755-81. . 1995b. Effects of gun seizures on gun violence: "Hot spots"patrol in KansasCity.Justice Quarterly 12 (4): 673-93. Sherman,LawrenceW.,Janell D. Schmidt, Dennis P. Rogan,PatrickR. Gartin,Ellen G. Cohn, Dean J. Collins, and AnthonyR. Bacich. 1991. From initial deterrence to long-term escalation:Short custody arrest for poverty ghetto domestic violence. Criminology29 (4): 1101-30. Sherman,LawrenceW, and David Weisburd. 1995. General deterrent effects of police patrol in crime "hot spots:"A randomized,controlled trial.Justice Quarterly 12 (4): 625-48. Skogan,Wesley G. 1990. Disorder and decline. New York:Free Press. S1992. Impact of policing on social disorder Summaryoffindings. Washington,DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Skogan,Wesley G., and Susan M. Hartnett. 1995. Communitypolicing Chicagostyle: Yeartwo. Chicago:Illinois CriminalJustice InformationAuthority

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REDUCING CRIME, DISORDER, AND FEAR

65

Skolnick,Jerome H., and David H. Bayley.1986. The new blue line: Police innovation in six Americancities. New York:Free Press. Spelman,William,and Dale K. Brown. 1981. Calling the police:A replicationof the citizen reportingcomponent of the Kansas City response time analysis. Washington, DC: Police Executive Research Forum. Trojanowicz,Robert. 1986. Evaluatinga neighborhoodfoot patrolprogram:The Flint, Michiganproject. In Community crime prevention:Does it work? edited by Dennis Rosenbaum. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Uchida, Craig, BrianForst, and SampsonO. Annan. 1992. Modernpolicing and the control of illegal drugs: Testingnew strategies in two Americancities. Washington,DC: National Institute of Justice. van Tulder,Frank. 1992. Crime, detection rate, and the police: A macro approach.Journal of Quantitative Criminology 8 (1): 113-31. Visher,Christy,and David Weisburd.1998. Identifyingwhat works:Recent trends in crime. Crime, Law and Social Change 28:223-42. Weiner, Kenneth, Kenneth Chelst, andWilliamHart. 1984. Stingingthe Detroit criminal:A total system perspective. Journal of CriminalJustice 12:289-302. Weiner, Kenneth, Christine K. Stephens, and Donna L. Besachuk. 1983. Making inroads into property crime: An analysisof the Detroit anti-fencingprogram.Journal of Police Scienceand Administration11 (3): 311-27. Weisburd,David. 1997. Reorientingcrime prevention researchand policy: From the causes of criminalityto the context of crime. Washington,DC: U.S. Government PrintingOffice. . 2003. Ethicalpractice and evaluationof interventionsin crime andjustice: The moralimperativefor randomizedtrials.Evaluation Review 27:336-54. Weisburd, David, and AnthonyA. Braga.2003. Hot spots policing. In Crime prevention:New approaches, edited by Helmut Kuryand Obergerfeld Fuchs. Mainz, Germany:Weisner Ring. Weisburd,David, and LorraineGreen. 1995a. Policing drug hot spots:The Jersey City drug marketanalysis experiment.Justice Quarterly 12 (4): 711-35. -. 1995b. Assessing immediate spatial displacement: Insights from the Minneapolishot spot experiment. In Crimeand place: Crimeprevention studies, vol. 4, edited by John E. Eck and David Weisburd. Monsey, NY:Willow Tree Press. Weisburd,David, and CynthiaLum. 2001. Translating researchinto practice:Reflections on the diffusionof crime mappinginnovation.Retrieved September 5, 2003, from http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij/maps/Conferences/01conf/Papers.html Weisburd, David, CynthiaLum, and AnthonyPetrosino. 2001. Does researchdesign affect study outcomes in criminaljustice? Annals of American Political and Social Science 578:50-70. Weisburd, David, Stephen Mastrofski,Anne Marie McNally,and Rosann Greenspan. 2001. Compstatand organizationalchange:Findingsfroma nationalsurvey. Washington,DC: NationalInstitute of Justice. Weisburd, David, Jerome McElroy,and PatriciaHardyman.1988. Challenges to supervisionin community policing: Observationson a pilot project.AmericanJournal of Police 7 (2): 29-50. Weisburd, David, and Faye Taxman.2000. Developing a multi-center randomizedtrialin criminology:The case of HIDTA.Journal of Quantitative Criminology 16 (3): 315-39. Weiss, Alexander,and Sally Freels. 1996. Effects of aggressive policing: The Dayton traffic enforcement experiment. AmericanJournal of Police 15 (3): 45-64. Whitaker,Gordon P, Charles Phillips, Peter Haas, and Robert Worden. 1985. Aggressivepolicing and the deterrence of crime. Law and Policy 7 (3): 395-416. Wilson, James Q., and BarbaraBoland. 1979. The effect of police on crime. Law and Society Review 12 (3): 367-90. Wilson, O. W 1967. Crime prevention-Whose responsibility?Washington,DC: Thompson Book. Wycoff, MaryAnn, and Wesley G. Skogan. 1986. Storefrontpolice offices: The Houston field test. In Community crime prevention:Does it work? edited by Dennis Rosenbaum. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. 1993. Community policing in Madison: Quality from the inside, out. Washington, DC: Police Foundation. Zhao, Jihong, Matthew C. Scheider, and Quint Thurman. 2002. Funding community policing to reduce crime: Have COPS grants made a difference? Criminologyand Public Policy 2 (1): 7-32.

This content downloaded from 189.220.27.251 on Tue, 9 Apr 2013 02:57:34 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)