Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Identifying Our Own Problems

Încărcat de

zerpthederpDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Identifying Our Own Problems

Încărcat de

zerpthederpDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

P O P U L AT I O N R E F E R E N C E B U R E AU

September 2006

IDENTIFYING OUR OWN PROBLEMS

Working With Communities for Participatory PHE Research

by Rainera L. Lucero, World Neighbors

etermining the most important development challenges at the community level can be difficult, especially when they entail complex cause-and-effect relationships across different sectors. This case study relates the story of how World Neighbors (a nongovernmental development organization) involved community members in identifying both critical development challenges and the relationships among those challenges in their community. World Neighbors then supported a process through which the community members formed a plan of action to achieve their goals in the areas of livelihoods, natural-resource management, and reproductive health.

Part 1: Problems in Cabacnitan

Background: Cabacnitan

Manila

Sea

Cabacnitan

The barangay (the Filipino term for a village, district, or ward) of Cabacnitan is located in the southern tip of Batuan, Bohol, a municipality in the Loboc Watershed. Loboc Watershed covers four protected areas: the Chocolate Hills National Ph Monument, the Rajah Sikatuna il ip pi National Park, the Loboc ne Se a Watershed Reforestation Project, and the Loay Marine Reserve. Cabacnitan occupies 311 hectares (about one-third of which is within the protected area) and is five kilometers from the national highway. It has a population of 785 people in 135 households (as of 2001) and has no barangay health station. Farming is the main occupation of its residents.

It was Monday afternoon. Lolo Jose was sitting on the floor by the doorstep of a bamboo house, listening to an old transistor radio. Lolo, I am back. How are you? said Inday, approaching her grandfather. Oh Inday, why are you back from the city? I did not expect to see you again until our town fiesta next month, Lolo Jose responded in surprise. I met an accident, Inday explained, sobbing. I am pregnant and my employer kicked me out. What will I do now? I can no longer work and help our family. Lolo Jose tried to get some water for Inday to drink but the jar was empty. He sighed and turned back to his granddaughter. It is okay, Inday, he said. It is not uncommon for a girl to get pregnant. Two of your friends also came back from Manila last month. They are pregnant just like you. Lolo Jose consoled Inday. Rene, a development worker with World Neighbors, came by. She stopped momentarily, wanting to join the conversation of the grandfather and granddaughter. Listening to them talking, Rene was speechless. She began to wonder how a development program could address a problem like Indays, a problem that was increasingly common in Cabacnitan. Other challenges were also mounting in the rural barangay. Rene had just come from a meeting with the barangay captain, who described to her how the farming situation of the barangay had changed over the years. Because irrigation water had become increasingly scarce, the people of the barangay were converting more and more of their rice fields into corn production. The farmers now felt it was better to grow corn since it needs less

www.prb.org

Strategies for Sustainable Development

So

uth

Ch

ina

2 IDENTIFYING OUR OWN PROBLEMS: Working With Communities for Participatory PHE Research

water and takes only three months from planting to harvest, while producing rice takes much longer. But even with these changes, the farmers worried that they were still not producing enough to adequately feed their families. Back in her office, Rene went through a shelf of reading materials, trying to find a model for programs that address such interrelated problems on a community level. She called up her friends in other NGOs, asking about projects that respond to the problems of teenage pregnancy, water scarcity, and food insecurity together, but met with no luck. She was frustrated. The following week, Rene returned to Cabacnitan and met Jojo, the technician fielded by the Soil and Water Conservation Foundation (SWCF) in Cabacnitan. Jojo told her that the SWCF had been working in Cabacnitan for three months and that it had conducted a naturalresource-management needs assessment of the barangay; he added that a farmers organization (BACOD) had been formed in the village to share information on sustainable farming practices. Renes face lit up. She was delighted to learn that some work had been done to address some of the difficult living conditions in Cabacnitan. However, there was still the challenge of addressing teenage pregnancy resulting from the outmigration of young girls to work in big cities. And she began to wonder if there were other problems that the people were not talking about. Why did Indays mother die? Rene wondered. Why did young girls have to leave Cabacnitan? Why did they get pregnant at a young age? How do the

women perceive this situation? What do men think about it? The next morning, Rene realized that the solution to Cabacnitans problems wasnt likely to be found in any of the books on her shelf. As an outsider, she knew she couldnt fully grasp the extent of the challenges in the barangay or understand how those challenges related to each other. The problems of the village could only be solved by the community itself, and Rene trusted that, with guidance and support, the women, men, and youth of the community had the capacity to reverse the villages worsening conditions and improve their lives. Rene also realized that the local government would need to be key players in the development process in Cabacnitan. She decided to talk with Babesa project coordinator for Kauswagan Community Social Development Center, World Neighbors partner in Cabacnitanabout how they might get the community involved in their efforts. Consulting Health Staff and Community Leaders Rene and Babes made a plan to get the community involved in addressing Cabacnitans challenges. As a first step, they met with Batuans municipal health officer and her staff. What kinds of reproductive health issues exist in your municipality? Babes asked the health workers. A young volunteer doctor told stories of adolescent boys and girls engaging in sexual activities, explaining that most, if not all, teenagers who marry do so because the young

www.prb.org

Strategies for Sustainable Development

IDENTIFYING OUR OWN PROBLEMS: Working With Communities for Participatory PHE Research 3

woman is pregnant. Dr. Nenita Tumanda, the municipal health officer, said she had female clients who had many children and wanted to use contraceptives. My department needs training on family planning to be able to help women who no longer want to have children, Dr. Tumanda said. Rene engaged the municipal health staff in a guided discussion on the reproductive health problems in the municipality. She put on the floor a large piece of paper with a table that helped identify the reproductive health problems of males and females at different ages. We have many cases of teenage pregnancy and reproductive tract infections affecting men 20 to 45 years old, offered one staff member. These issues were two among many health problems identified by the Batuan health staff. To narrow down their knowledge of the community health conditions to Cabacnitan, which is just one barangay among many in the municipality, Rene and Babes engaged the village leaders of Cabacnitan in the same process. The discussion showed that Inday was not at all an isolated case. One community member explained that the conflict between the government and the New Peoples Army, a communist-based revolutionary group in the Philippines, had resulted in disoriented social relationships in the community; consequentially, sexual values and interaction in the barangay had changed. Others confirmed that childbearing before and beyond marriage had started to become a common occurrence.

The barangay officials and the officers of BACOD who participated in the discussion decided to further investigate their problems by doing a community needs assessment on reproductive health. Together, they drew up a set of criteria for identifying research volunteers who would be trained to collect data for the community needs assessment. They decided they would recruit volunteers who could read and write, hear and listen, do simple calculations, had respect within the community, and could commit time to the research activity.

Discussion Questions 1. What problems do you see in Cabacnitan, and how do you think they might be related? 2. Why did Rene think it was necessary to involve the community in identifying and addressing the problems of the barangay? What are the biggest benefits of involving the community in development projects? 3. What kinds of challenges do you think Rene and Babes might face in getting the community to be involved? 4. Why did Rene and Babes begin by consulting the municipal health staff? What are the advantages of using this approach?

Strategies for Sustainable Development

www.prb.org

4 IDENTIFYING OUR OWN PROBLEMS: Working With Communities for Participatory PHE Research

Part 2: Training Community Volunteers

Once the barangay officials had identified a group of research volunteers from the community, Babes talked with each of them to describe their tasks and find out their preferences for the time and place of the training as well as their needs for transportation or other kinds of support. A month later, Babes and Rene convened the group to provide an orientation to the goals of their work and provide the necessary research-skills training. There were 14 community research volunteers, with one man and one woman from each of the seven puroks (administrative subdivisions) in Cabacnitan. Rene engaged the volunteer researchers in a series of experiential learning exercises. Using the information on reproductive health issues that Rene and Babes had gathered from the municipal health staff and community leaders, the volunteers developed questions on these issues for use in focus groups and a household questionnaire. The issues included sexual behavior; family planning; health conditions of women during pregnancy, childbirth, and after delivery; health practices; and gender relations. The volunteers pretested their new Focus Group Discussion Guides and Household Survey Questionnaire among themselves, practicing asking questions and writing down responses. Collecting Data The volunteer researchers were now ready to begin their research among community members in the barangay. Equipped with supplies and materials from Kauswagan and supported by Che-che, a Kauswagan community organizer, the research

volunteers collected data in focus group discussions and household surveys throughout the next month. Male researchers interviewed and facilitated focus group discussions among male respondents, while female researchers did the same with female respondents. Kauswagan provided meals for the research volunteers and focus group discussion participants. The information gathered in these focus group discussions was used to further refine the household survey questionnaire. For example, the family planning methods men and women separately identified during focus group discussions were listed in the household questionnaire as possible responses. The results of the household survey showed the extent of use of each of the family planning methods in the village. Sustaining the Interest of Volunteer Researchers Rene and Babes realized that they would need to plan carefully to keep the research volunteers motivated and engaged throughout the data collection process. In addition to providing meals, materials, and uniform shirts to the volunteers and community members during the focus group discussions, Rene and Babes planned periodic check-ins with the team of volunteers. During these check-in meetings, Rene and Babes solicited feedback on the volunteers work such as inspiring stories and challenging situations. They also provided guidance on the next steps for the volunteers. They kept on reminding them that their leadership and untiring efforts could awaken the community to initiate changes toward their own development.

www.prb.org

Strategies for Sustainable Development

IDENTIFYING OUR OWN PROBLEMS: Working With Communities for Participatory PHE Research 5

Rainera L. Lucero

Analyzing and Presenting Results Over the next several weeks, the volunteers collected, collated, and analyzed the research data. They then put the results onto charts and presented their work to the community through a barangay assembly. The presentation was attended by officials of the municipal governmentincluding the barangay captain, the municipal health officer, the midwife assigned in the barangay, the municipal social welfare and development officer, and those municipal councilors representing local committees on health and women. After hearing the presentation, the community members attending the assembly affirmed that the survey results were correct and the problems it identified were true. The municipal health officer listened while the people discussed why the community had low adoption rates of family planning methods and why they preferred traditional birth attendants to professional midwives. The discussion boiled down to the absence of a health station in the village and the discouragement community members had met when they tried to visit the health station in the next barangay or Rural Health Unit. The village meeting ended with the formation of a group of community planners from among the volunteer researchers from each of the puroks. Barangay leaders selected representatives who had the following characteristics: They had creative ideas; they were critical thinkers; they were openminded, expressive, enthusiastic, optimistic, and sincere; and they could commit time to attend an extensive planning workshop. The 12 barangay planners included seven women and five men ages 23 to 63. After the community confirmed the needs identified during the assessment, the villagers got ready for developing community plans to address

Volunteers in Cabacnitan examine the range of problems identified through the community needs assessment.

their needs. The following month, the community planning team made a cross-visit to a reproductive health project in San Miguel, Bohol, to learn the approaches that project used to address reproductive health problems at the community level.

Discussion Questions 5. Which techniques did Rene and Babes use to ensure full participation from the research volunteers? What other strategies have you used to recruit and retain volunteers? 6. Rene and Babes recruited one male and one female research volunteer from each purok in Cabacnitan. Why might they have thought this balance was important? 7. Why would Rene and Babes ask the research volunteers to present the results instead of presenting the data themselves?

Strategies for Sustainable Development

www.prb.org

6 IDENTIFYING OUR OWN PROBLEMS: Working With Communities for Participatory PHE Research

Part 3: Taking Action Through the Community Planning Workshop

With the communitys needs identified and with community research volunteers having obtained ideas on how to address these problems, Rene and Babes facilitated a workshop through which the volunteer community planners formed their community development plan. The planners reviewed all the problems and issues that emerged from the research, including those on natural-resource management and reproductive health. They wrote these issues on large cards that were then spread out on the floor. They connected the problems with arrows indicating cause/effect relationships, creating a problem tree. One cardlow farm production and incomehad many arrows coming in and out of it, and the planners agreed this was their main problem. They used the problem tree to demonstrate how the other problems related to low farm production and income (see Box 1). Renes attention was rapt as the planners traced and explained the cause/effect relationships of the problems identified in the problem tree. Having many children results in more family needs and low income, explained Nang Ale, one

of the planners. The family size grows, but the farm size doesnt. The farm gets smaller and smaller as parents divide their land among their children. When farms are overused due to the pressure to produce food for the family, they become less and less productive, added Noy Meling, another member of the planning team. We are forced to move into the forest because the soil there is still fertile. However, I have noticed that water for the rice fields has receded. I think it is the result of kaingin (clearing land from trees and shrubs by cutting and burning them and using the land for agriculture). Nang Ebing stood up and pointed to the arrow she had drawn linking low production and income to out-migration and teenage pregnancies. Families are forced to send their young girls to Manila to work as house helpers so that they could send back money to their families, she explained. However, many of them come home pregnant because of sexual abuse and unsafe sexual relationships with peers of the opposite sex in Manila. The process allowed the community planners to identify and illustrate the links among these

Box 1

Problem Tree Analysis

Problem tree analysis is a community activity for analyzing data from a community needs assessment to be used for community planning. It is carried out using blank cards, large sheets of paper, marking pens, and masking tape. Community representatives review the needs and problems identified in the needs assessment, write each of them on a blank card, and spread them out on a wide sheet of paper. With marking pens, the participants trace the cause/effect relationships of the needs and problems. They draw arrows from a cause card to an effect card, keeping in mind that a need or a problem can be both a cause and an effect. The need/problem with the most number of arrows coming in and going out is considered the main problem (the tree trunk). Tracing back, the needs/problems with arrows going into the main problem are considered the causes (the tree roots), and those with arrows coming out of the main problem are considered the effects (the tree branches and leaves). On another sheet of large paper, the participants arrange the cards to make the problem tree. From the problem tree, the community develops its plan.

www.prb.org

Strategies for Sustainable Development

IDENTIFYING OUR OWN PROBLEMS: Working With Communities for Participatory PHE Research 7

reproductive health and natural-resource management problems. Using the problem tree, the community planners drafted their action plans with a set of objectives, timeframes, responsible persons, locally available resources, and other necessary resources. After the workshop, Rene wore a big smile. She was very happy looking back at the entire process. She saw that the regular meetings with the community volunteers to share updates and feedback (as well as to decide on the next steps) had been one of the keys to sustaining the volunteers interest and ensuring their ongoing involvement. The community needs assessment uncovered the answers to many of Renes questions. It brought the communitys problems to the surface and clearly showed how each related to another. The assessment also made people think and talk about the relationships among the problems as well as to begin to plan how to address them in a holistic manner. Next Challenges In December, Babes and Rene sat down together to draw up a program that would support the community in implementing their community development plan. Babes and Rene recognized that taking action as soon as possiblewhile the community volunteers had the memory of the community planning workshop fresh in their

mindswas critical to maintaining the momentum of their work. The new year saw Babes working with the municipal and barangay governments to identify strategies to increase capacity in the community in Cabacnitan and to support them in the implementation of their plans. With the united support and engagement of the community, Babes and Rene were confident that the community had made an important first step in addressing its development challenges.

Discussion Questions 8. Are participatory approaches for community research particularly useful for projects that involve issues from different sectors such as health and economic development? Why or why not? 9. Sustaining community involvement over long periods of time can be a challenge. What kind of advice might you give to Rene and Babes in their efforts to ensure effective participatory processes throughout the implementation of the community development plan? 10. This is one example of an approach to participatory research and planning. What other kinds of approaches or methods have you learned about or used in your own work?

Strategies for Sustainable Development

www.prb.org

8 IDENTIFYING OUR OWN PROBLEMS: Working With Communities for Participatory PHE Research

Acknowledgments

This case study was written by Rainera L. Lucero, Philippines Program Coordinator for World Neighbors. The author would like to thank Purita (Babes) Sanchez for reviewing the content of her work, Dr. Cel Habito for being her mentor in developing the case study, and Kathleen Mogelgaard for guiding her as she wrote the story and inspiring her to move forward amidst heavy work demands. PRB gratefully acknowledges the assistance of individuals who reviewed and commented on this case study, including Antonio La Vina, World Resources Institute; Robin Marsh, University of California, Berkeley; and Melissa Thaxton and Nancy Yinger, PRB. Robert Lalasz edited the case study; Michelle Corbett designed it. This case study was produced with the support of the David and Lucile Packard Foundation; and the University of Michigan Population Fellows Programs, which are funded by the Office of Population and Reproductive Health at the United States Agency for International Development. September 2006, Population Reference Bureau

PRBs Population, Health, and Environment (PHE) Program works to improve peoples lives around the world by helping decisionmakers understand and address the consequences of population and environment interactions for human and environmental well-being. Since 2001, the PHE Program has worked with partner NGOs in the Philippines to build organizational capability for crosssectoral development programming; to expand the application of integrated development approaches; and to increase policymakers knowledge and understanding of population, health, and environment dynamics. The PHE Program engages in similar activities in other countries and regions around the world. For more information on PRBs PHE Program, please write to PHE@prb.org. The Population Reference Bureau informs people around the world about population, health, and the environment, and empowers them to use that information to advance the well-being of current and future generations. For more information, including membership and publications, please contact PRB or visit our website: www.prb.org.

POPULATION REFERENCE BUREAU

1875 Connecticut Ave., NW, Suite 520, Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel.: 202-483-1100 | Fax: 202-328-3937 | E-mail: popref@prb.org Website: www.prb.org

www.prb.org

Strategies for Sustainable Development

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Chem Trails HAARP Mind ControlDocument60 paginiChem Trails HAARP Mind ControlGiannis FakirisÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Halo Effect Research ProposalDocument8 paginiThe Halo Effect Research ProposalOllie FairweatherÎncă nu există evaluări

- Keeping Foster Youth Off The Streets: Improving Housing Outcomes For Youth That Age Out of Care in New York City,"Document63 paginiKeeping Foster Youth Off The Streets: Improving Housing Outcomes For Youth That Age Out of Care in New York City,"Noah FranklinÎncă nu există evaluări

- EMS Checklist: (ISO 14001 Model)Document25 paginiEMS Checklist: (ISO 14001 Model)Femi Kolawole100% (1)

- 12 Literary Compositions That Have Influenced The WorldDocument3 pagini12 Literary Compositions That Have Influenced The Worldzerpthederp100% (6)

- Sap Standard QM ReportsDocument5 paginiSap Standard QM Reportsamittal111100% (1)

- Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports for Preschool and KindergartenDe la EverandPositive Behavior Interventions and Supports for Preschool and KindergartenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Session 4: Main SymptomsDocument86 paginiSession 4: Main SymptomszerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Community DiagnosisDocument9 paginiCommunity Diagnosisunsp3akabl3100% (2)

- Banahao Women AssociatonDocument3 paginiBanahao Women AssociatonBJ quimpanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alleviating Poverty/Advancing Prosperity: An Essential Guide for Helping the PoorDe la EverandAlleviating Poverty/Advancing Prosperity: An Essential Guide for Helping the PoorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Community DiagnosisDocument31 paginiCommunity DiagnosisMae Arra Lecobu-anÎncă nu există evaluări

- Welcome AddressDocument1 paginăWelcome AddresszerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study of A Patient With Ischemic CardiomyopathyDocument33 paginiCase Study of A Patient With Ischemic Cardiomyopathyromeo rivera80% (5)

- Where India Goes: Abandoned Toilets, Stunted Development and the Costs of CasteDe la EverandWhere India Goes: Abandoned Toilets, Stunted Development and the Costs of CasteEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (5)

- PESTLE Analysis On Coca ColaDocument3 paginiPESTLE Analysis On Coca Colavinayj07Încă nu există evaluări

- Equal Partners: Improving Gender Equality at HomeDe la EverandEqual Partners: Improving Gender Equality at HomeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (3)

- CYSTOCLYSISDocument1 paginăCYSTOCLYSISzerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Copar OutputDocument147 paginiCopar OutputLovie dovieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barangay Cabacnitan: Community SituationerDocument2 paginiBarangay Cabacnitan: Community SituationerAdrian OblenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tabug 12H3 Case2Document3 paginiTabug 12H3 Case2Pogi OmarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Community Needs Assessment: Group 1Document6 paginiCommunity Needs Assessment: Group 1Lovely De CastroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rural Immersion ProgramDocument10 paginiRural Immersion ProgramWORST NIGHTMAREÎncă nu există evaluări

- Movie CriticDocument2 paginiMovie CriticJanine TugononÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proceedings Report of Womengirlsatthecenterofcovid19Document12 paginiProceedings Report of Womengirlsatthecenterofcovid19Mikasa ElizaldeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interview Assignment - CorpuzDocument8 paginiInterview Assignment - Corpuzcarlojay.corpuzÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Community Is A Home of People Who Are Together in One Place While Achieving A Goal To Keep The OrderlinessDocument1 paginăA Community Is A Home of People Who Are Together in One Place While Achieving A Goal To Keep The OrderlinessPia BondocÎncă nu există evaluări

- The History of Visayan Village: Tagum City'S Most Populated BarangayDocument11 paginiThe History of Visayan Village: Tagum City'S Most Populated BarangayJay Jay JayyiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monique Viet Nam Chapter Oct 17Document9 paginiMonique Viet Nam Chapter Oct 17Shaista FalakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Groupomar Community Observation2Document4 paginiGroupomar Community Observation2Pogi OmarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unpaid Work, Poverty and Women's RightsDocument7 paginiUnpaid Work, Poverty and Women's Rightsbigyan12Încă nu există evaluări

- BPI Round 3 - ADRA - UpdatedDocument11 paginiBPI Round 3 - ADRA - UpdatedInterActionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Title of The Project:-Help Handicapped Childern and Old PeopleDocument10 paginiTitle of The Project:-Help Handicapped Childern and Old PeopleHimanshu SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annual Progress ReportsDocument12 paginiAnnual Progress ReportsVIJAY PAREEKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wash Connector Newsletter Issue VII 2018Document32 paginiWash Connector Newsletter Issue VII 2018Emperorr Tau MtetwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jhoanna Salve S. Bordeos - Summary of InterviewDocument1 paginăJhoanna Salve S. Bordeos - Summary of InterviewJhoanna BordeosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dec. 2 Maa Feature EditedDocument4 paginiDec. 2 Maa Feature EditedMary May AbellonÎncă nu există evaluări

- CSR Assignment 5 PDFDocument5 paginiCSR Assignment 5 PDFMasumiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revised Group WorkDocument9 paginiRevised Group WorkHanabusa Kawaii IdouÎncă nu există evaluări

- YALC Voice: Speak Ou T!Document4 paginiYALC Voice: Speak Ou T!YUWAnepalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Groupwork Casestudy To Be RevisedDocument20 paginiGroupwork Casestudy To Be RevisedRovern Keith Oro CuencaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ramsha Nusrat Daily Report FDocument69 paginiRamsha Nusrat Daily Report FArisha NusratÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rams ReportDocument74 paginiRams ReportArisha NusratÎncă nu există evaluări

- Identification of A Social Problem: Case of San Pio Village Talisay CebuDocument6 paginiIdentification of A Social Problem: Case of San Pio Village Talisay CebuPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ramsha Daily ReportsDocument22 paginiRamsha Daily ReportsArisha NusratÎncă nu există evaluări

- Buklod Tao SynthesisDocument17 paginiBuklod Tao SynthesisClarinda MunozÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interview 11Document5 paginiInterview 11Fariha AktarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Report NGODocument31 paginiFinal Report NGOpranit katleÎncă nu există evaluări

- PTFT 2 - COMMUNITY IMMERSION Pt. 1 Group 5BDocument7 paginiPTFT 2 - COMMUNITY IMMERSION Pt. 1 Group 5Bhellotxt304Încă nu există evaluări

- Project in FCL-4Document8 paginiProject in FCL-4Chelcee Ulnagan CacalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Senior Project Proposal Form SAMPLEDocument8 paginiSenior Project Proposal Form SAMPLENikkie SalazarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Compiled FCA 103Document151 paginiCompiled FCA 103Bryan YanguasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Report (Batch 2021-23) Title of The Project: Spreading Awareness On Health and HygieneDocument28 paginiFinal Report (Batch 2021-23) Title of The Project: Spreading Awareness On Health and HygieneKASTURI P (Marketing 21-23)Încă nu există evaluări

- Payatas ImmersionDocument4 paginiPayatas ImmersionJoann Zyrell SalazarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bana Research Executive SummaryDocument2 paginiBana Research Executive SummaryTauqeer TariqÎncă nu există evaluări

- CO ContentDocument312 paginiCO ContentJonas Dela Cruz100% (1)

- Annexure 1 Community Develpoment: Submitted by Shreya MahajanDocument27 paginiAnnexure 1 Community Develpoment: Submitted by Shreya MahajanShreya MahajanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Flood Affected People in Pakistan 2010Document9 paginiFlood Affected People in Pakistan 2010Malick M. Rehan AlviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yes, I'm HereDocument5 paginiYes, I'm Herebiuangela60Încă nu există evaluări

- UNDP - NP - Social Mobilisation in Nepal PDFDocument8 paginiUNDP - NP - Social Mobilisation in Nepal PDFMukesh PokharelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study Set A Group 1Document84 paginiCase Study Set A Group 1Almendral FitsgeraldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Community Report FINALDocument223 paginiCommunity Report FINALBriene MembrereÎncă nu există evaluări

- 12B Lardizabal FinalPTDocument7 pagini12B Lardizabal FinalPTKyle Vincent LardizabalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bright Horizons Summer 2016Document4 paginiBright Horizons Summer 2016BHcareÎncă nu există evaluări

- 412 Community AnaylsisDocument8 pagini412 Community Anaylsisapi-727613303Încă nu există evaluări

- Sanitation Services Improves Health and Lives of I-Kiribati Women (Dec 2016)Document6 paginiSanitation Services Improves Health and Lives of I-Kiribati Women (Dec 2016)ADBGADÎncă nu există evaluări

- Day 1 Thursday Attendance Check OrientationDocument16 paginiDay 1 Thursday Attendance Check OrientationDummy AccountÎncă nu există evaluări

- Community SlideDocument16 paginiCommunity SlideRasmei Rath100% (1)

- Gender and Society ActivitiesDocument4 paginiGender and Society ActivitiesMa Josella SalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Working With Women in Conflict-Affected Areas: A Gender Advocate's ThoughtsDocument2 paginiWorking With Women in Conflict-Affected Areas: A Gender Advocate's ThoughtsADBGADÎncă nu există evaluări

- Compilation OF Case Studies: Perpetual Succour Hospital Gorordo Ave., Lahug, Cebu City Nursing Service DepartmentDocument1 paginăCompilation OF Case Studies: Perpetual Succour Hospital Gorordo Ave., Lahug, Cebu City Nursing Service DepartmentzerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Requirements For Perpetual Succour Hospital PGNTDocument1 paginăRequirements For Perpetual Succour Hospital PGNTzerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drusadg Study For Paracetamol Omeprazole and Vitamin B ComplexDocument3 paginiDrusadg Study For Paracetamol Omeprazole and Vitamin B ComplexzerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- When in Rome PDFDocument120 paginiWhen in Rome PDFzerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

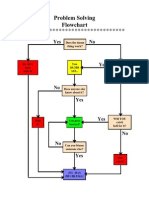

- Problem Solving Flowchart: Yes NoDocument1 paginăProblem Solving Flowchart: Yes NozerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grand Cassade Study 1Document15 paginiGrand Cassade Study 1zerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Community Needs AssessmentDocument13 paginiCommunity Needs Assessmentzerpthederp0% (1)

- Dunkin DonutsDocument2 paginiDunkin DonutszerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- TOPICDocument1 paginăTOPICzerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sponsorship LetterDocument3 paginiSponsorship LetterzerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liquidation Form UBSSGDocument1 paginăLiquidation Form UBSSGzerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- PVB Properties For Sale 2010 PDFDocument24 paginiPVB Properties For Sale 2010 PDFzerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Presentation Final2Document36 paginiCase Presentation Final2zerpthederpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monitoring and Evaluation Framework For Inclusive Smart Cities in IndiaDocument28 paginiMonitoring and Evaluation Framework For Inclusive Smart Cities in IndiaNaumi GargÎncă nu există evaluări

- (IJCST-V3I3P47) : Sarita Yadav, Jaswinder SinghDocument5 pagini(IJCST-V3I3P47) : Sarita Yadav, Jaswinder SinghEighthSenseGroupÎncă nu există evaluări

- SeedsGROW Progress Report: Harvesting Global Food Security and Justice in The Face of Climate ChangeDocument77 paginiSeedsGROW Progress Report: Harvesting Global Food Security and Justice in The Face of Climate ChangeOxfamÎncă nu există evaluări

- SPSS Course ContentDocument2 paginiSPSS Course ContentRockersmalaya889464Încă nu există evaluări

- Books Held in Psychology Test Library (As at 26 July 2012)Document13 paginiBooks Held in Psychology Test Library (As at 26 July 2012)Idham AnwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foundation Unit 7 Topic TestDocument19 paginiFoundation Unit 7 Topic TestLouis SharrockÎncă nu există evaluări

- SSC 202 Statistical Methods and Sources II-1Document106 paginiSSC 202 Statistical Methods and Sources II-1onifade faesolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recruitment & Selection Process in Textile Sector With Reference To Coimbatore DistrictDocument5 paginiRecruitment & Selection Process in Textile Sector With Reference To Coimbatore DistrictMaryamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tracer Study of Stiis Bsba GraduatesDocument4 paginiTracer Study of Stiis Bsba GraduatesAnonymous yElhvOhPnÎncă nu există evaluări

- AJHP Pharmacy Forecast 2018-3Document32 paginiAJHP Pharmacy Forecast 2018-3tpatel0986Încă nu există evaluări

- Writing A Recommendation in A Research Paper ExampleDocument8 paginiWriting A Recommendation in A Research Paper Examplenydohavihup2Încă nu există evaluări

- Definition and Nature of ResearchDocument20 paginiDefinition and Nature of ResearchJiggs LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Darin Surka 2008Document89 paginiDarin Surka 2008elisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2023 Action Research Strengthening Co-Curricular Activities in School To Minimize Cyberbullying in Grad 8 StudentsDocument14 pagini2023 Action Research Strengthening Co-Curricular Activities in School To Minimize Cyberbullying in Grad 8 StudentsGretelou SuganoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annotated BibliographyDocument7 paginiAnnotated Bibliographyapi-241420031Încă nu există evaluări

- The Unresponsive Bystander: Are Bystanders More Responsive in Dangerous Emergencies?Document13 paginiThe Unresponsive Bystander: Are Bystanders More Responsive in Dangerous Emergencies?Kerima DelibašićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors Influencing Customer Satisfaction Through Purchase Decision at Ramayana Department StoreDocument9 paginiFactors Influencing Customer Satisfaction Through Purchase Decision at Ramayana Department StoreAnonymous izrFWiQÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electromagnetism Demonstration ScriptDocument5 paginiElectromagnetism Demonstration ScriptEswaran SupramaniamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soyoung CVDocument6 paginiSoyoung CVapi-477306025Încă nu există evaluări

- Assignment 1Document2 paginiAssignment 1abbasi sameerÎncă nu există evaluări

- RFL Company Profile 2013 Final (2.44 MB)Document17 paginiRFL Company Profile 2013 Final (2.44 MB)Fido DidoÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Do Students View Online LearningDocument20 paginiHow Do Students View Online LearningmyramarcelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culture and Congruence The Fit Between Management Practices and National Culture - NEWMANDocument27 paginiCulture and Congruence The Fit Between Management Practices and National Culture - NEWMANRodrigo MenezesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategic ManagementDocument103 paginiStrategic ManagementMayur KrishnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Economics - AssignmentDocument5 paginiBusiness Economics - AssignmentAkshatÎncă nu există evaluări