Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Hamlet - Tragedie Teme

Încărcat de

Muntean Diana CarmenDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Hamlet - Tragedie Teme

Încărcat de

Muntean Diana CarmenDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Hamlet

by William Shakespeare Major Themes Death Death has been considered the primary theme of Hamlet by many eminent critics through the years. G. Wilson Knight, for instance, writes at length about death in the play: Death is o!er the whole play. "olonius and #phelia die during the action, and #phelia is buried before our eyes. Hamlet arranges the deaths of $osencrant% and Guildenstern. &he plot is set in motion by the murder of Hamlet's father, and the play opens with the apparition of the Ghost. (nd so on and so forth. &he play is really death) obsessed, as is Hamlet himself. (s as (.*. +radley has pointed out, in his !ery first long speech of the play, #h that this too solid flesh, Hamlet seems on the !erge of total despair, kept from suicide by the simple fact of spiritual awe. He is in the strange position of both wishing for death and fearing it intensely, and this double pressure gi!es the play much of its drama. #ne of the aspects of death which Hamlet finds most fascinating is its bodily facticity. We are, in the end, so much meat and bone. &his strange intellectual being, which Hamlet !alues so highly and possesses so mightily, is but tenuously connected to an unruly and decomposing machine. ,n the gra!eyard scene, especially, we can see Hamlet's fascination with dead bodies. How can -orick's skull be -orick's skull. Does a piece of dead earth, a skull, really ha!e a connection to a person, a personality. Hamlet is unprecedented for the depth and !ariety of its meditations on death. /ortality is the shadow that darkens e!ery scene of the play. 0ot that the play resol!es anything, or settles any of our species)old doubts and an1ieties. (s with most things, we can e1pect to find !ery difficult and stimulating 2uestions in Hamlet, but !ery few satisfying answers. Intrigue 3lsinore is full of political intrigue. &he murder of #ld Hamlet, of course, is the primary instance of such sinister workings, but it is hardly the only one. "olonius, especially, spends nearly e!ery waking moment 4it seems5 spying on this or that person, checking up on his son in "aris, instructing #phelia in e!ery detail of her beha!ior, hiding behind tapestries to ea!esdrop. He is the parody of a politician, con!inced that the truth can only be known through the most roundabout and sneaking ways. &his is ne!er clearer than in his appearances in (ct &wo. 6irst, he instructs $eynaldo in the most incredibly con!oluted espionage methods7 second, he hatches and pursues his misguided theory that Hamlet is mad because his heart has been broken by #phelia. *laudius, too, is 2uite the inept /achia!ellian. He nai!ely in!ites 6ortinbras to march across his country with a full army7 he stupidly enlists $osencrant% and Guildenstern as his chief spies7 his attempt to poison Hamlet ends in total tragedy. He is little better than "olonius. &his political ineptitude goes a long way toward re!ealing how weak Denmark has become under *laudius' rule. He is not a natural king, to be sure7 he is more

interested in drinking and se1 than in war, reconnaissance, or political plotting. &his is partly why his one successful political mo!e, the murder of his brother, is so ironic and foul. He has somehow done away with much the better ruler, the Hyperion to his satyr 4as Hamlet puts it5. ,t's worth noting that there is one e1tremely capable politician in the play )) Hamlet himself. He is always on top of e!eryone's moti!es, e!eryone's doings and goings. He plays "olonius like a pipe and e!ades e!ery effort of $osencrant% and Guildenstern to do the same to him. He sniffs out *laudius' plot to ha!e him killed in 3ngland and sends his erstwhile friends off to die instead. Hamlet is a true /achia!ellian when he wants to be. He certainly wouldn't ha!e been as warlike as his father, but had he gotten the chance he might ha!e been his father's e2ual as a ruler, simply due to his penetration and acumen. Language ,n (ct &wo scene two "olonius asks Hamlet, What do you read, my lord. Hamlet replies, Words, words, words. #f course e!ery book is made of words, e!ery play is a world of words, so to speak, and Hamlet is no different. Hamlet is distinguished, howe!er, in its attenti!eness to language within the play. 0ot only does it contain e1tremely rich language, not only did the play greatly e1pand the 3nglish !ocabulary, Hamlet also contains se!eral characters who show an interest in language and meaning in themsel!es. "olonius, for instance, is often distracted by his manner of e1pressing himself. ,n (ct &wo scene two, for e1ample, he says, /adam, , swear , use no art at all. 8 &hat he is mad, 'tis true: 'tis true 'tis pity, 8 (nd pity 'tis 'tis true. ( foolish figure, 8 +ut farewell to it, for , will use no art. #f course this is typical "olonius )) absurdly hypocritical, self) enamored, dull)witted. 9ust as he is e1tremely windy in recommending bre!ity, here he is fussy and artful 4or affectedly artificial5 in declaring that he is neither of those things. "olonius' grasp of language, like his political instinct, is 2uite shallow )) he gestures toward the mastery of rhetoric that seems like a statesman's primary craft, but he is too distracted by surfaces to achie!e any real depth. (nother angle from which to consider language in the play )) Hamlet e1plores the traditional dichotomy between words and deeds. ,n (ct 6our, when talking to :aertes, *laudius makes this distinction e1plicit: what would you undertake, 8 &o show yourself your father's son in deed 8 /ore than in words. Here deeds are associated with noble acts, specifically the fulfillment of re!enge, and words with empty bluffing. &he passage resonates well beyond its immediate conte1t. Hamlet himself is a master of language, an e1plorer of its possibilities7 he is also a man who has trouble performing actual deeds. 6or him, reality seems to e1ist more in thoughts and sentences than in acts. &hus his trouble fulfilling re!enge seems to stem from his o!eremphasis on reasoning and formulating )) a fault of o!er)precision that he acknowledges himself in the speech beginning, How all occasions do inform against me. Hamlet is the man of language, of words, of the magic of thought. He is not fit for a play that so emphasi%es the !alue of action, and he knows it. +ut then, the action itself is contained within words, formed and contained by Shakespeare's pen. &he action of the play is much more an illusion than the words are. Hamlet in!ites us to consider whether

this isn't the case more often than we might think, whether the world of words doesn't en;oy a great deal of power in framing and describing the world of actions, on stage or not. Madness +y the time Hamlet was written, madness was already a well)established element in many re!enge tragedies. &he most popular re!enge tragedy of the 3li%abethan period, &he Spanish &ragedy, also features a main character, Hieronymo, who goes mad in the build)up to his re!enge, as does the title character in Shakespeare's first re!enge tragedy, &itus (ndronicus. +ut Hamlet is uni2ue among re!enge tragedies in its treatment of madness because Hamlet's madness is deeply ambiguous. Whereas pre!ious re!enge tragedy protagonists are unambiguously insane, Hamlet plays with the idea of insanity, putting on an antic disposition, as he says, for some not)perfectly)clear reason. #f course, there is a practical ad!antage to appearing mad. ,n Shakespeare's source for the plot of Hamlet, (mneth 4as the legendary hero is known5 feigns madness in order to a!oid the suspicion of the fratricidal king as he plots his re!enge. +ut Hamlet's feigned madness is not so simple as this. His performance of madness, rather than aiding his re!enge, almost distracts him from it, as he spends the great ma;ority of the play e1hibiting !ery little interest in pursuing the ghost's mission e!en after he has pro!en, !ia &he /ouse &rap, that *laudius is indeed guilty as sin. 0o wonder, then, that Hamlet's madness has been a resilient point of critical contro!ersy since the se!enteenth century. &he traditional 2uestion is perhaps the least interesting one to ask of his madness )) is he really insane or is he faking it. ,t seems clear from the te1t that he is, indeed, playing the role of the madman 4he says he will do ;ust that5 and using his !eneer of lunacy to ha!e a great deal of fun with the many fools who populate 3lsinore, especially "olonius, $osencrant% and Guildenstern. "erhaps this feigned madness does at times edge into actual madness, in the same way that all acted emotions come !ery close to their genuine models, but, as he says, he is but mad north) northwest, and knows a hawk from a handsaw. When he is alone, or with Horatio, and free from the need to act the lunatic, Hamlet is incredibly lucid and self)aware, perhaps a bit manic but hardly insane. So what should we make of his feigned insanity. Hamlet, in keeping with the play in general, seems almost to act the madman because he knows in some bi%arre way that he is playing a role in a re!enge tragedy. He knows that he is e1pected to act mad, because he thinks that that is what one does when seeking re!enge )) perhaps because he has seen &he Spanish &ragedy. ,'m ;oking, of course, on one le!el, but he does e1hibit self)aware theatricality throughout the play, and if he hasn't seen &he Spanish &ragedy, he has certainly seen &he Death of Gon%ago, and many more plays besides. He knows his role, or what his role should be, e!en as he is unable to play it satisfactorily. Hamlet is beautifully miscast as the re!enger )) he is constitutionally unfitted for so !ulgar and unintelligent a fate )) and likewise his attempt to play the madman, while a !aliant effort, is forced, insincere, an1ious, ambiguous, and full of doubts. "erhaps Hamlet himself, if we could ask him, would not know why he chooses to feign madness any more than we do.

0eedless to say, Hamlet is not the only person who goes insane in the play. #phelia's madness ser!es as a clear foil to his own strange antics. She is truly, unambiguously, innocently, simply mad. Whereas Hamlet's madness seems to increase his self)awareness, #phelia loses e!ery !estige of composure and self)knowledge, ;ust as the truly insane tend to do. Subjectivity Harold +loom, speaking about Hamlet at the :ibrary of *ongress, said, &he play's sub;ect massi!ely is neither mourning for the dead or re!enge on the li!ing. ... (ll that matters is Hamlet's consciousness of his own consciousness, infinite, unlimited, and at war with itself. He added, Hamlet disco!ers that his life has been a 2uest with no ob;ect e1cept his own endlessly burgeoning sub;ecti!ity. +loom is not the only reader of Hamlet to see such an emphasis on the self. Hamlet's solilo2uies, to take only the most ob!ious feature, are strong and sustained in!estigations of the self )) not only as a thinking being, but as emotional, bodily, and parado1ically multiple. Hamlet, fascinated by his own character, his turmoil, his inconsistency, spends line after line wondering at himself. Why can't , carry out re!enge. Why can't , carry out suicide. He 2uestions himself, and in so doing 2uestions the nature of the self. (side from these massi!e speeches, Hamlet shows a sustained interest in philosophical problems of the sub;ect. (mong these problems is the mediating role of thought in all human life. 6or there is nothing good or bad, but thinking makes it so, he says. We can ne!er know the truth, he suggests, nor the good, nor the e!il of the world, e1cept through the means of our thoughts. *ertainty is not an option. (nd the great realm of uncertainty, the realm of dreams, fears, thoughts, is the realm of sub;ecti!ity. Suicide :ike madness, suicide is a theme that links Hamlet and #phelia and shapes the concerns of the play more generally. Hamlet thinks deeply about it, and perhaps contemplates it in the more popular sense7 #phelia perhaps commits it. ,n both cases, the ma;or upshot of suicide is religious. ,n his two suicide solilo2uies, Hamlet segues into meditations on religious laws and mysteries )) that the 3!erlasting had not fi1ed 8 His canon 'gainst self) slaughter 7 6or in that sleep of death what dreams may come. (nd #phelia's burial is greatly limited by the clergy's suspicions that she might ha!e taken her own life. ,n short, Hamlet appears to suggest that were it not for, first, the social stigma attached to suicide by religious authorities, and second, the legitimately unknown nature of whate!er happens after death, there would be a lot more self)slaughter in this difficult and bitter world. ,n a play so obsessed with the self, and the nature of the self, it's only natural to see this emphasis on self)murder. ,t's worth mentioning one of the ma;or interpreti!e issues of Hamlet: was #phelia's death accidental or a suicide. (ccording to Gertrude's narration of the e!ent, #phelia's drowning was entirely accidental. Howe!er, some ha!e suggested that Gertrude's long story may be a fabrication in!ented to protect the young woman from the social stigma of suicide. ,ndeed, in (ct 6i!e the priest and the gra!ediggers are fairly

certain that #phelia took her own life. #ne might ask oneself )) why does it make such a difference to us whether she died by her own hand or not. Shakespeare seems, in fact, to inspire this !ery sort of self)interrogation. (re we, like the characters in the play, so in!ested in protecting #phelia from the stigma of suicide. Theater Which is the star of this play, Hamlet or Hamlet. &.S. 3liot, for one, une2ui!ocally endorses the latter: 6ew critics ha!e e!er admitted that Hamlet the play is the primary problem, and Hamlet the character only secondary. ,n effect, Hamlet is a play about plays, about theater. /ost ob!iously, it contains a play within a play, detailed instructions on acting techni2ue, an e1tended con!ersation about :ondon theater companies and their fondness for boy troupes, se!eral references to other theater 4including to *hristian mystery plays, and to Shakespeare's own 9ulius *aesar5, and still more references to the stage on which it is being performed, in the globe theater with its ghost in the cellarage. +ut what is the point of this constant metatheatrical winking. Hamlet, among other things, is an e1tended meditation on the nature of acting and the relationship between acting and genuine life. ,t refuses to obey the con!entional restrictions of theater and constantly spills out into the audience, as it were, pointing out the real surroundings of the fictional play, and thus incorporating them into the larger theatrical e1perience. /ost specifically, Hamlet is an e1ploration of a specific genre and its specific generic con!entions. ,t is the re!enge tragedy to end all re!enge tragedies, both containing and commenting on the elements that define the genre. /odern audiences are 2uite comfortable with this sort of meta)generic approach. &hink of modern westerns, heist mo!ies, or martial arts mo!ies. (ll of these genres ha!e become almost obligatorily self)aware7 they contain references to past milestones in their respecti!e genres, they gleefully and ironically embrace 4or alternati!ely re;ect5 the con!entions that past films treated with sincerity. Hamlet, in its relationship to re!enge tragedy and to theater more generally, is one of the first dramas of this kind and perhaps still the most profound e1ample of such post)modern concerns. &o put it cutely, Hamlet itself is the main character of the play, and Hamlet merely the means by which it e1plores its own place in the history of theater. &o make things yet di%%ier, Hamlet seems, deep down, to know that he is in a play, to know that he is miscast, to understand the theatrical nature of his being. (nd who's to say that we aren't all merely actors in our own li!es. Surely, from a philosophical perspecti!e, this is one of the basic truths of modern human life.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

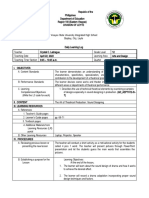

- Lesson PlanDocument3 paginiLesson PlanMuntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notes On Victorian Poetry A-B Ciocoi-PopDocument204 paginiNotes On Victorian Poetry A-B Ciocoi-PopMuntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extremely Loud and Incredibly CloseDocument8 paginiExtremely Loud and Incredibly CloseMuntean Diana Carmen100% (1)

- Litere Engleza Licenta 2014Document3 paginiLitere Engleza Licenta 2014Muntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- ElaborariDocument63 paginiElaborariMuntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Alexandria Quartet 1Document3 paginiThe Alexandria Quartet 1Muntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Incredibly Loud and Extremily CloseDocument50 paginiIncredibly Loud and Extremily CloseMuntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gimnaziul de Stat Tudor Vladimirescu Prof. Raduly Dana-MariaDocument3 paginiGimnaziul de Stat Tudor Vladimirescu Prof. Raduly Dana-MariaMuntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Midsummer'a Night Dream - Comedie RezumatDocument3 paginiA Midsummer'a Night Dream - Comedie RezumatMuntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hamlet - Tragedie RezumatDocument4 paginiHamlet - Tragedie RezumatMuntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Worksheet 1 Look at The Pictures and Write The Color and The Object Where Is NecessaryDocument1 paginăWorksheet 1 Look at The Pictures and Write The Color and The Object Where Is NecessaryMuntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hamlet - Tragedie RezumatDocument4 paginiHamlet - Tragedie RezumatMuntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cuprins The Great GatsbyDocument1 paginăCuprins The Great GatsbyMuntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bibliografie The Great GatsbyDocument1 paginăBibliografie The Great GatsbyMuntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson PlanDocument3 paginiLesson PlanMuntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan: TH THDocument5 paginiLesson Plan: TH THMuntean Diana CarmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Harold Athol Fugard DLB BiosDocument23 paginiHarold Athol Fugard DLB BiosL786Încă nu există evaluări

- Daily Learning LogDocument4 paginiDaily Learning LogCrystal Castor LabragueÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHAPTER 9 - Play Production 1Document5 paginiCHAPTER 9 - Play Production 1Justine Vistavilla PagodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Waiting For GodotDocument2 paginiWaiting For GodotBonocore Anastasia PiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Expert B2 - Stop and Check 3 - Units 5 To 8Document3 paginiExpert B2 - Stop and Check 3 - Units 5 To 8Lucio AvinteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contemporary Theatre ReviewDocument13 paginiContemporary Theatre ReviewHanafi MulyadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arts - Module 1 - Quarter 4) Week1-Week2Document24 paginiArts - Module 1 - Quarter 4) Week1-Week2gloria tolentino50% (2)

- Chapter 1-2Document22 paginiChapter 1-2Lain PadernillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chamber TheaterDocument2 paginiChamber TheaterFelice RecellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PG AUD 03: Spies in DisguiseDocument4 paginiPG AUD 03: Spies in DisguiseHana the PrincessÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Baking Can DoDocument15 paginiWhat Baking Can Dolily ellis80% (5)

- Writing Sample Letter To The DirectorDocument5 paginiWriting Sample Letter To The Directorapi-285253245Încă nu există evaluări

- Multiplex 06-12 PDFDocument27 paginiMultiplex 06-12 PDFsarker dadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Descriptive AssignmentDocument4 paginiDescriptive AssignmentRul UlieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lila Hovey Costume ResumeDocument1 paginăLila Hovey Costume Resumeapi-414992137Încă nu există evaluări

- LIT17 ANC G11 LA ReDrDocument2 paginiLIT17 ANC G11 LA ReDrHeba SahsahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Robert Cohen, James Calleri - Acting Professionally - An Essential Career Guide For The Actor (2024, Methuen Drama)Document313 paginiRobert Cohen, James Calleri - Acting Professionally - An Essential Career Guide For The Actor (2024, Methuen Drama)Gergely BereczkiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crticism - Cinema ParadisoDocument3 paginiCrticism - Cinema ParadisoBam DeduroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arts Quiz IvDocument35 paginiArts Quiz IvJoyce Gozun Roque33% (3)

- SOP Prajina KhadkaDocument2 paginiSOP Prajina KhadkaI m legend kcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Top 250 MoviesDocument1 paginăTop 250 MoviesMina AiadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Romeo and JulietDocument29 paginiRomeo and JulietGAREN100% (3)

- The City and The Countryside Reading-ComprehensionDocument1 paginăThe City and The Countryside Reading-ComprehensionDraco BroncoÎncă nu există evaluări

- JT Nagle ResumeDocument1 paginăJT Nagle Resumeapi-265562096Încă nu există evaluări

- As You Like It - WikipediaDocument12 paginiAs You Like It - WikipediaHeaven2012Încă nu există evaluări

- General Skills AuditDocument3 paginiGeneral Skills Auditapi-501779888Încă nu există evaluări

- Advantage2 UNIT 3 MorePracticeDocument6 paginiAdvantage2 UNIT 3 MorePracticealgarestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fosse/Verdon: Episode 108 "Providence"Document53 paginiFosse/Verdon: Episode 108 "Providence"MPÎncă nu există evaluări

- GESE G3 - Classroom Activity 2 - Directions, Places and JobsDocument4 paginiGESE G3 - Classroom Activity 2 - Directions, Places and JobsPaula Alcañiz López-TelloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Four Little GirlsDocument31 paginiFour Little GirlsRaffaele CastaldoÎncă nu există evaluări