Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Teachers Decision-Making Power and School Conflict-Net

Încărcat de

做挾持Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Teachers Decision-Making Power and School Conflict-Net

Încărcat de

做挾持Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Polytechnic College of La Union Agoo, La Union

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements in EdM211 Human Behavior in Organization

REACTION PAPER

Submitted to:

DR. ALICIA F. APRECIO

Submitted by:

GENNETE STELLERA S. FRIGILLANA

Teachers Decision-Making Power and School Conflict The distribution and effects of power in school systems have been two of the most important issues in both educational research and policy since the 1980s. there has been a great deal of interest in which persons or groups have power in schools, that is, who controls school decisions concerned with key activities and what difference it makes for how well schools function. Indeed, such issues are at the crux of many significant contemporary educational reforms-school-based-management, school choice, restructuring, and the professionalization of teachers. However, although both researchers and policymakers in the field of education have increasingly recognized that the distribution of power in school systems is an important issue, the subject has been marked by substantial disagreement and confusion. One area of disagreement is the degree to which schools ought to be centralized or decentralized. For example, some reformers have contended that too much decentralization in school systems is a primary cause of disorder and inefficiency in the operation of schools and, ultimately, poor performance by staff and students. They believe that the educational system would greatly benefit from an increase in the centralized control and accountability of school programs and staff. Other reformers, however, have argued the opposite-that too much centralization in school systems is the main cause of disorder and inefficiency in the operation of schools and, in the end, of poor performance by staff and students. In their view, the educational system would greatly benefit if decision making was delegated to the local and school levels. Furthermore, this debate has suffered from a great deal of confusion because different researchers and policy analysts have, at different groups, on different levels of analysis, and on different aspects of power. For instance, some discussions of decentralization have concentrated on input from parents and local communities into school policy, while others have stressed the empowerment of teachers and school staff. Some analysts have been concerned with an interorganizational level of analysis and on the interface between state or district agencies and school-level staff, while other have been interested in an intraorganizational level and on the interface between teachers and administrators in schools. In addition, different researchers have focused on different kinds, forms, and aspects of power. For instance, some have been concerned with the mechanisms and degree of organizational control of teachers and their work, while others have been interested in the degree of professional authority collectively exercised by school faculty, and still others have stressed the effects of the amount of autonomy teachers exercise in their individual classrooms. Given this variation in emphases, it is not surprising that researchers have come to different conclusions about the distribution and effects of power in schools. Moreover, the resolution of this debate has been hampered by the shortage of empirical studies devoted to specifying and examining which kinds and aspects of power have what effects on which outcomes in school, and why.

REACTION A positive climate, particularly a high degree of cooperation and cohesion among key groups, is important for the performance of schools. The character of the relations among students and staff is at the crux of the normative and socialization functions of schools. The amounts of teachers autonomy and influence make an important difference for the amount of cooperation or conflict in schools. It is for those decisions that are fundamentally social-when the educational process involves the selection, maintenance, and transmission of behaviors and norms-that the association between teachers lack of power and conflict in schools is th e strongest. Indeed, autonomy and influence over instructional activities appear to count for little if teachers do not also have power over decisions concerned with socialization and sorting activities. The attitudes and behaviors that are stereotypically associated with the bureaucratic personality and with female managers-authoritarianism, rigid rule following, inflexibility, and fear of able subordinates-are akin to intervening variables. They result from a lack of power and contribute further to problems with subordinates, superordinates, and peers. But whether managers exhibit positive human relations with their subordinates is less crucial than their levels of power over the core productive issues for which they are responsible. That is, better relations with less pleasant but empowered superordinates than with more pleasant disempowered superordinates. Teachers are also caught between the contradictory demands and needs of their subordinates-principals-and their subordinates-students-in that they are responsible not only for increasing the motivation and performance of students, but for implementing school policies set by administrators. At the crux of their role and success as men in the middle is their level of power: Teachers with power over decisions related to tasks for which they are responsible can exert influence; have a greater sense of commitment and higher aspirations; and, in turn, garner respect from both subordinates and superordinates. On the other hand, if their authority to carry out school policies is not sufficient to accomplish the tasks for which they are responsible, teachers will meet neither groups needs. Teachers who have little power are less able to get things done and have less credibility. Students can more easily challenge or ignore them, and principals can more easily neglect to back them. In such cases, teachers may feel pressured to turn to manipulative or authoritarian methods to get the job done, which may simply exacerbate tensions with their students and fellow staff members. Hence, conflict between teachers and their students can be considered a specific instance of a phenomenon that is important in all kinds of organizations; if the influence and responsibility of employees are not commensurate, there will be problems in the workplace. What a schools social norms are to be and who is to make such decisions is a key issue of organizational control. These indicate that increasing teachers power over such decisions will eliminate these domains of conflict. The efforts to reform schools ought to decentralize power over social policies. Such reforms rarely focus on a similar expansion of teachers power over the crucial social policies of schools, such as the determination of who may attend the school and who may not, how the students will be tracked, and what behavior will be allowed and not allowed. Autonomy and influence over instructional activities will count for little if teachers do not also have power over fundamental socialization and sorting activities. It may be precisely because basic issues of school socialization and sorting are important societal functions and are of great concern to parents, students, school administrators, and larger constituencies that they are so centrally controlled.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Inclusive Education Lived Experiences of 21st Century Teachers in The PhilippinesDocument11 paginiInclusive Education Lived Experiences of 21st Century Teachers in The PhilippinesIJRASETPublications100% (1)

- Stages Teacher Development..Document73 paginiStages Teacher Development..Darrel WongÎncă nu există evaluări

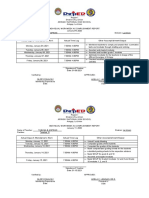

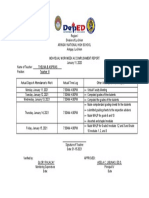

- DLL EAPP 1 and 2Document10 paginiDLL EAPP 1 and 2Louise ArellanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self-Introduction SampleDocument8 paginiSelf-Introduction Sampleabubaker mohamedtoom100% (1)

- MMSU Clothing Construction SyllabusDocument11 paginiMMSU Clothing Construction Syllabuscharmaine100% (3)

- Majorship English BlessingsDocument13 paginiMajorship English BlessingsCamille Natay100% (8)

- COMPUTER SYSTEM SERVICING NC II Work Immersion ModuleDocument114 paginiCOMPUTER SYSTEM SERVICING NC II Work Immersion ModuleLAWRENCE ROLLUQUIÎncă nu există evaluări

- GSP Action Plan 2016-2017Document4 paginiGSP Action Plan 2016-2017Gem Lam Sen89% (9)

- Teaching Math in Intermediate GradeDocument4 paginiTeaching Math in Intermediate GradeBainaut Abdul SumaelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Itec 7500 - Capstone Experience Portfolio 1Document10 paginiItec 7500 - Capstone Experience Portfolio 1api-574512330Încă nu există evaluări

- Technology For Teaching and LearningDocument40 paginiTechnology For Teaching and LearningApril Grace Genobatin BinayÎncă nu există evaluări

- BHW Report Sta. CeciliaDocument5 paginiBHW Report Sta. Cecilia做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- English ModuleDocument8 paginiEnglish Module做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Learn About Your Target CountryDocument6 paginiLearn About Your Target Country做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Failure in SchoolDocument3 paginiFailure in School做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Individual Work Week Grade 7Document20 paginiIndividual Work Week Grade 7做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- PesoSense Ipon Challenge 2019 CalendarDocument1 paginăPesoSense Ipon Challenge 2019 Calendar做挾持100% (2)

- BCPC Plan 2018 - DSWD FormatDocument1 paginăBCPC Plan 2018 - DSWD Format做挾持100% (1)

- BARANGAY ANTI-DRUG ABUSE COUNCIL PLANDocument3 paginiBARANGAY ANTI-DRUG ABUSE COUNCIL PLAN做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- IPCRF SummaryDocument1 paginăIPCRF Summary做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- INDIVIDUAL WORK WEEK GRADE 9 and 10Document1 paginăINDIVIDUAL WORK WEEK GRADE 9 and 10做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Elleen P. Estilong: Signed in The Presence ofDocument1 paginăElleen P. Estilong: Signed in The Presence of做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- BARANGAY ANTI-DRUG ABUSE COUNCIL PLANDocument3 paginiBARANGAY ANTI-DRUG ABUSE COUNCIL PLAN做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- 2017 English 6 Learning Competency Planner RepairedDocument18 pagini2017 English 6 Learning Competency Planner Repaired做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Kasar DORISDocument7 paginiKasar DORIS做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- House of Representatives: MessageDocument1 paginăHouse of Representatives: Message做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Certificate of DedicationDocument1 paginăCertificate of Dedication做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Jenny Joy - I: Her Royal HighnessDocument1 paginăJenny Joy - I: Her Royal Highness做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Abubo Soriano 3foldsDocument2 paginiAbubo Soriano 3folds做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Right Here Waiting for YouDocument1 paginăRight Here Waiting for You做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- La Union Standard Academy Periodical Examination Science 8: ST NDDocument3 paginiLa Union Standard Academy Periodical Examination Science 8: ST ND做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- WEEKLY STORE SALES REPORT HIGHLIGHTS KEY METRICSDocument1 paginăWEEKLY STORE SALES REPORT HIGHLIGHTS KEY METRICS做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- SBFP San Simon EsDocument4 paginiSBFP San Simon Es做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Itinerary of Travel: Monthly SalaryDocument2 paginiItinerary of Travel: Monthly Salary做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Answer SheetDocument3 paginiAnswer Sheet做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- La Union Standard Academy Periodical Examination Science 8: ST NDDocument3 paginiLa Union Standard Academy Periodical Examination Science 8: ST ND做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- SBFP Pang WestDocument12 paginiSBFP Pang West做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Christ The Living Stone FellowshipDocument4 paginiChrist The Living Stone Fellowship做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Character Traits BlankDocument1 paginăCharacter Traits Blank做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Auto Loan App: Personal & Financial DetailsDocument2 paginiAuto Loan App: Personal & Financial Details做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- 5 Auto TechnicianDocument1 pagină5 Auto Technician做挾持Încă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Language Tests and Testing PracticesDocument24 paginiUnderstanding Language Tests and Testing Practiceseduardo mackenzieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Animal Behavior Project ProposalDocument6 paginiAnimal Behavior Project Proposalapi-487903964Încă nu există evaluări

- Digital Morning Meeting LessonDocument9 paginiDigital Morning Meeting Lessonapi-561660834Încă nu există evaluări

- Ashna ReportDocument10 paginiAshna ReportAshna MamandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Secondary UnitDocument36 paginiSecondary Unitapi-649553832Încă nu există evaluări

- Carpeta GladysDocument16 paginiCarpeta GladysGladys Marleny Alva LeonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foundations of Educations (Drill)Document5 paginiFoundations of Educations (Drill)Rommel BansaleÎncă nu există evaluări

- SPH4U Course OutlineDocument3 paginiSPH4U Course OutlineShakib FirouziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essential Elements of Effective Lesson PlanningDocument3 paginiEssential Elements of Effective Lesson PlanningPujari VaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Finland Malays: Main Source(s) of FinancingDocument63 paginiFinland Malays: Main Source(s) of FinancingBrendon JikalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weekly Lesson Plan: Canaawan High School I. ObjectivesDocument4 paginiWeekly Lesson Plan: Canaawan High School I. ObjectivesVivian ValerioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Education Paper 5 ENGLISHDocument80 paginiEducation Paper 5 ENGLISHRabia ChohanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weekly Learning Plan Q1W1Document2 paginiWeekly Learning Plan Q1W1sagiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yeshivat He'Atid Annual Report 2013Document11 paginiYeshivat He'Atid Annual Report 2013pixelkatestudioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art HumourDocument25 paginiArt HumourDanÎncă nu există evaluări

- PE Week 3Document6 paginiPE Week 3Emperor'l BillÎncă nu există evaluări

- Happy ClassroomDocument2 paginiHappy Classroomapi-557754395Încă nu există evaluări

- Action Research On Student and Pupil Absenteeism in SchoolDocument12 paginiAction Research On Student and Pupil Absenteeism in SchoolEvangelene Esquillo Sana100% (1)

- What's On in Dushanbe: Welcome To La Grande DameDocument25 paginiWhat's On in Dushanbe: Welcome To La Grande DameFarrukh BulbulovÎncă nu există evaluări