Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Port of Singapore Authority - Students Copy v2

Încărcat de

yatinsethi20062013Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Port of Singapore Authority - Students Copy v2

Încărcat de

yatinsethi20062013Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Port of Singapore Authority

Singapores most important natural resources include its large, protected harbour, its location on major trade routes, and the skills of its well-educated workforce. Singapore is located where ship traffic between Europe and Southeast Asia and the U.S. West Coast and Southeast Asia must pass; it is a natural entry for products shipped to and from neighbouring countries. A port requires massive infrastructure development including berths, cranes, trucks, storage, and warehousing, anchorages, tugboats, and pilot launches, particularly after shipping becomes containerized. Early in the history, Singapore opened its economy to foreign investment. As its economy grew, it allocated significant amounts of capital to developing its port. The 1997 Annual Report reviews the development of the modern port; the portion since developing container facilities is the most significant:

The Beginning of Containerisation PSA boldly proceeded to design and construct a container terminal in the late 1960s. The first 300metre berth was completed in 1972, and the first container vessel, m.v. Nihon, arrived in June that year. Productivity took a quantum leap. With goods packed in metal containers and handled by quay cranes, 53 tonnes of cargo per man hour were handled, representing a 136-fold increase in productivity when compared to the days before 1972. Tanjong Pagar Terminal (TP) ended the landmark year of 1972 by handling 24,515 TEUs, using two quay cranes. For the next ten years, an average of 100,000 TEUs were added to PSAs container volume every year. The additional volume had to be accommodated by building new capacity berths were progressively added to TPT. By 1981, another milestone was reached, with TPT celebrating the record of its first million TEUs within a year. Container Transhipment Hub As significant as PSAs achievements in the 1970s were, they were surpassed by the meteoric growth which characterised the 1980s the result of the pioneering of the hub-and-spoke container shipping concept in the region. By investing in massive berth facilities and sophisticated equipment and computer systems, PSA began to attract large container ships on global trade routes. From the megacarriers, large numbers of containers were discharged on each call at PSA, for distribution to the region, while large numbers of containers, which had arrived from regional countries for consolidation at PSA, were also loaded on the same call. PSA had become the container transhipment hub port of the region. Such a wide network of connections has enhanced PSAs value as a hub port for container transhipment, and has been made possible because of the support of the global ocean carriers and the common-user feeder operators serving the region. The network of feeder services ensures cost-effective, reliable and frequent services for mainline operators, ultimately benefiting the entire logistics chain in the region. As the 1980s progressed, container volume poured in. From one million TEUs in 1981, our volume grew quickly to 4.36 million TEUs by 1989. By then, our value-added per employee had increased 13 percent per annum from $39,056 in 1980 to $ 116,613. PSA once again determined to innovate and improve in order to stay at the forefront of the industry, in the face of greater demands on its container-handling capacity. The conventional wharves at Keppel Terminal were converted into container berths on a large scale. The unprecedented volume also increased the scale and complexity of operations so tremendously that manual terminal operations were no longer

possible. PSA adapted to the changing situation by taking anoth er major step: introducing computer systems linking both terminal and marine operations, based on real-time information, to direct every job by every worker and every piece of equipment. By 1995, PSA achieved more than 10 ntimes the container throughput of 1982.

Path Followed Singapore recognized that its location was a natural resource that could give it a competitive advantage in economic development. Singapore has little agriculture and in 1960s, the industrial base was relatively small. Singapore has to be sure that its port remains viable to safeguard its manufacturing base and export-oriented policy. There are other locations astride or near the major Europe-Asia trade routes, and other harbours could be developed. Singapore has developed a system of resources for competitive advantage. The country opened its economy to foreign investment, resulting in economic growth and the ability to allocate significant amounts of capital to developing its port. Foreign investments also created a demand for transportation infrastructure, including ocean shipping. Singapores location and the harbour itself made a compelling case for applying capital to the port. IT initiatives became high priority applications to make it easier to route cargo through Singapore. We can see that investment and technology interact with location and harbour in this system of resources. The advantages of Singapores port are matched by several disadvantages, the most significant being the small size of the island. Space is at a premium, which creates operational problems for loading and unloading containers. Singapore applied Operations and IT to minimize this physical disadvantage. For example, the PSA uses technology to track, assign, and locate containers in the yard. It uses planning heuristics to stack and retrieve containers higher than other ports, while minimizing handling. The PSA also has other strategies that contribute to its competitive advantage. The first is a constant focus on customer service; the objective is to minimize ship turnaround times and to produce highquality handling. Second is the development of other ports and hubs to feed traffic to Singapore along with the creation of value-added services to maintain shipper loyalty, for example, systems to manage empty containers and to provide warehousing services. Operations at the Port Port operations have always been a key success factor for the PSA. Being situated in a strategic geographic location has its advantage but it is not the determining factor for the PSA to become the number one trans-shipment port in the world. The East-West sea lanes have many strategically located ports, such as Hong Kong, Port Klang (Malaysia), Colombo (Sri Lankan) and Kaohsiung (Taiwan). However, more than one hundred container shipping lines choose to call at the PSA. On an average day, there are three sailings to the Unites States, four to Japan, five to Europe and twenty-two to South Asia and South-East Asia. The PSA is connected to 740 ports in 130 countries. This kind of high-volume traffic requires efficient port operations. Key customer requirements in port operations include freight rates, frequency of services, shipping options, turnaround time, port charges , support services (ship maintenance and supplies), and feeder operations. Port customers are essentially the shipping lines; however,

it must be noted that shipping lines often take their cue from manufacturers, exporters, and the large buyers of goods and raw materials. As Singapore is a trans-shipment hub for shippers, port operations are very demanding. Arriving containers destined for other port destinations have to be transferred to other ships or stacked for later shipment, while containers destined for Singapore are placed on trailers for local delivery. These operations have to be well coordinated to maximize port resources and minimize ship turnaround times. Before ships arrive in Singapore, the shipping companies send a message to the PSA through the PortNet system. The company indicates when the ship will be arriving and applies for berthing spaces. Information sent to PortNet includes the number of containers on board, their arrangement, destination, and promised arrival date. Application for port call can be made between one month and twenty-four hours before the ship arrives. Once PSA receives the application, operations planning begins. Port personnel use the Computer Integrated Terminal Operations System(CITOS) to create plans for ship berthing and for unloading containers. Unloading plans have to specify whether the container will be picked up from the terminal, transferred to another ship immediately, or stacked for later shipment. The system also has to handle imports and exports for the domestic market. When the ship arrives, it docks at a specified time at its assigned berth. A specific number of quay cranes are assigned to service the ship based on the number of containers to be unloaded and loaded. Prime movers (special trucks that carry two containers) in the port move the containers from the ship to the stacking yard. At the stacking yard, cranes stack and unstuck the containers. Containers in the yard are placed in an initial holding area. Internal yard operations restack the containers in appropriate places and sequence to await eventual loading onto another ship or for pickup for domestic delivery by freight forwarders. Containers originating from Singapore exporters are handled by gate operations and routed to the stacking yard first, before eventual loading onto ships. CITOS determines the stack locations. The PSA anticipated global containerization in the late 1960s and built the first container port in the region. It also made early preparations to harness IT on a major scale and used it strategically in its port operations in the 1980s. The PSA is expanding its terminal facilities to meet the challenges of globalization, and concomitant anticipated cross-border trade growth. Although loading and unloading containers is the key operation in shaping the success of the PSA, there are a number of support features or enablers that make the port operation highly effective and help sustain its competitive edge. First, Singapore has the eighth largest merchant fleet in the world, 3,380 ships with 20.77 million gross tons (The Business Times, August 21, 1998). Singapore had total external trade amounting to S$382 billion in 1997 (approximately U.S. $224 billion, based on 1997 exchange rates), and the country is a major oil refinery center. Second, the PSA is the largest owner of warehouse space in Singapore, managing over 500,000 square meters of space. With its warehouse business, the PSA attempts to provide value added services to its traditional port operations, including the storage of goods and empty containers, labelling, repackaging, tagging, sampling and testing, quality control, and billing. The aim is to

establish an integrated global logistics network that connects Singapore to major regions such as Asia, Western Europe, China, India, and the U.S. Third, the PSAs workforce is trained to focus on customers. A quality culture is prevalent in the organization. The port has programs such as Key Customer Managers and Chat Time. The Key Customer Managers program provides regular dialogue sessions with customers, helping PSA staff to better understand and attend to customers operational and contractual needs. To promote a quality culture in the workforce, the PSA has widespread quality circles (QC) and encourages staff suggestions. Staff suggestions and QC projects have saved PSA about ten million Singapore dollars over the last five years. In 1999, the PSA won the Singapore Quality Award (SQA), which is given annually to an organization that has shown consistent business excellence in achieving world-class quality standards in its operations. The PSA has been able to harness these enablers and integrate them into its overall information and operations technology strategy to transform itself into a major regional transhipment hub for container shipping. The PSA has invested heavily in information and operations technology, both to solve immediate operating problems and to remove constraints on the growth of traffic. ------------most imp TradeNet: One of the first trade-related technological innovations in Singapore was TradeNet. The Trade Development Board (TDB) sponsored the design of this EDI system to facilitate the processing of trade documents. Prior to the development of the system, a large number of clerks processed batches of forms to clear shipments in and out of Singapore. The EDI system links the TDB, customs, shipping agents, ports, freight forwarders, traders and others. After the system was installed, the turnaround time for documents that formerly had taken two days to process dropped to fifteen minutes, while documents that used to require four days could normally be handled in four hours. TradeNet has greatly facilitated document processing, and it has removed time considerations for most of the parties who use it. Port operations, on the other hand, impose severe, real-time requirements on information processing. Effective customer service, which is measured by minimum ship turnaround time and error free container handling, imposes significant constraints on information processing and port operations. The PSA, in combination with various partners, developed an integrated set of traditional and expert systems to provide customer service to shipping lines. There are two major systems and many subsystems that allow the port to provide superb service despite the shortage of land area for storing and moving containers. CITOS: The Computer Integrated Terminal Operations System (CITOS), supports the planning and management of all port operations. The subsystems in CITOS process information for allocating berths or ships, planning the stowage of containers, allocating resources in general, reading container numbers, and operating trucking gates. Prior to the arrival of a ship, shippers notify the port authority of the containers that will be loaded using PortNet, an online system with about fifteen hundred subscribers. The PSA replies with a window of time for the shippers trucks to appear at an entry gate to the port. Its objective is to have trucks go to the right stack of containers and to have a yard crane

available to offload the container on the truck. Such scheduling minimizes the need to handle containers. The Container Number Recognition System uses a video camera for each letter and number of the eleven-character container ID. A neural net recognizes each character, and the system checks it against its record of the container that was expected. The gate automation subsystem also records the weight and directs the driver to the containers location within forty-five seconds. This system has reduced the number of individuals manually checking Ids from sixteen, one per lane, to three. The Ship Planning Subsystems deals with the loading and unloading of containers, positioning the containers inside a vessel, the allocation of quay cranes alongside the vessel, and the sequence in which the cranes will operate. This problem is complex because ships typically carry cargo to several destinations; it is important to minimize handling by loading containers in the right sequence. The Yard Planning Expert Subsystem sorts containers to support fast turnaround. One of its objectives is to use space efficiently and keep yard activities orderly. It must be sure that containers are accessible to avoid unnecessary handling and movements. The Resource Allocation Subsystem assigns all operations staff and container handling equipment with the exception of the quay cranes. CIMOS: The Computer-Integrated Marine Operations System helps to manage shipping traffic and the activities of the sort. It includes a Vessel Traffic Information Subsystem that watches the Singapore Straits and approaches to the port using five remote radars. Another set of four radars monitors port waters; this subsystem sends information to expert systems that plan the deployment of tugboats, pilots, and launches. All of this information is available in a database that shippers access via PortNet to learn the status of vessels in the port. There are five expert systems used for planning including applications to assign ships to anchorages, schedule the movement of vessels through channels to terminals, deploy pilots to tugs and launches, route launches, and deploy tugboats. Note that these systems are highly asset-specific; they have almost no applicability outside a port, and the size of Singapores port makes them inappropriate for many smaller ports. The systems also interact to strengthen port resources. TradeNet reduces the cycle time for processing trade documents, which encourages shippers to use the port. CITOS reduces the cycle time for loading and unloading ships, a further benefit to customers. Key Performance Data Singapore is the busiest port in the world in terms of shipping tonnage; at any one time, there are more than 800 ships in port. In 1997, Singapore received 130,333 vessels with a shipping tonnage of 808.3 million gross tons. It handles a throughput of 14.12 million TEUs in its container terminals in 1997. PSA facilities can provide on average 88 container moves per hour. In comparison, Chinas ports handled a total of 10.77 million TEUs in container services in 1997. Hong Kong had 14.5 million TEUs in 1997 while South Korea handled about 6 million TEUs in 1996. Taiwans main port at Kaoshiung had 7.87 million TEUs in 1996. However, these are all

larger countries than Singapore, and the containers in the country are handled by more than one port operator.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Group 1 - LenovoDocument17 paginiGroup 1 - Lenovoyatinsethi20062013100% (1)

- Port Agency 2014Document3 paginiPort Agency 2014Deepak Shori100% (1)

- ThesexualharassmentofwomenatworkplaceDocument26 paginiThesexualharassmentofwomenatworkplaceyatinsethi20062013Încă nu există evaluări

- VodafoneDocument27 paginiVodafoneyatinsethi20062013Încă nu există evaluări

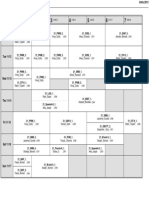

- Time Table (Term-5) FMG-21 and IMG-6, Week-9 PDFDocument1 paginăTime Table (Term-5) FMG-21 and IMG-6, Week-9 PDFyatinsethi20062013Încă nu există evaluări

- Michel Mor Is SetDocument30 paginiMichel Mor Is SetDheeraj KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case CadburyDocument10 paginiCase Cadburyyatinsethi20062013Încă nu există evaluări

- Case CadburyDocument10 paginiCase Cadburyyatinsethi20062013Încă nu există evaluări

- Michel Mor Is SetDocument30 paginiMichel Mor Is SetDheeraj KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- KKHS, Homework Class 9Document65 paginiKKHS, Homework Class 9yatinsethi20062013Încă nu există evaluări

- Case CadburyDocument10 paginiCase Cadburyyatinsethi20062013Încă nu există evaluări

- Case CadburyDocument10 paginiCase Cadburyyatinsethi20062013Încă nu există evaluări

- Exercise - 1 (Discriminant Analysis)Document1 paginăExercise - 1 (Discriminant Analysis)yatinsethi20062013Încă nu există evaluări

- Case CadburyDocument10 paginiCase Cadburyyatinsethi20062013Încă nu există evaluări

- Post Graduate Diploma in Management (FMG-21) (2013-2014) Schedule of Summer Project PresentationsDocument4 paginiPost Graduate Diploma in Management (FMG-21) (2013-2014) Schedule of Summer Project Presentationsyatinsethi20062013Încă nu există evaluări

- Urban Rural DetailsDocument20 paginiUrban Rural Detailsakibpagla001Încă nu există evaluări

- BurgasDocument7 paginiBurgasEvrenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Title For Cruise LineDocument6 paginiThesis Title For Cruise Linetfwysnikd100% (2)

- Atp4 48Document48 paginiAtp4 48Studio JackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Transport & Logistics On Indonesia Trade CompetitivenessDocument69 paginiImpact of Transport & Logistics On Indonesia Trade CompetitivenessAndre SimangunsongÎncă nu există evaluări

- DEEP WATER PORT NOTES - Mar 2012Document5 paginiDEEP WATER PORT NOTES - Mar 2012Patricia DillonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guidelines 10th Part I (Last Update Jul22 2011)Document217 paginiGuidelines 10th Part I (Last Update Jul22 2011)danielÎncă nu există evaluări

- R.A. 9295Document8 paginiR.A. 9295Anonymous zDh9ksnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pier PlanDocument13 paginiPier PlanERIKA MAE ROSARIOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design PrinciplesDocument173 paginiDesign PrinciplesZainab Hamayun LodhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Calica Final AidDocument12 paginiCalica Final AidKryshia Anne CalicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mammoet 2004Document8 paginiMammoet 2004Cuong DinhÎncă nu există evaluări

- SINGAPORE General ServicesDocument7 paginiSINGAPORE General ServicesinongchinÎncă nu există evaluări

- SAP Gioia Tauro Terminal ProblemDocument26 paginiSAP Gioia Tauro Terminal Problemapi-3750011Încă nu există evaluări

- Dust Prevention in Bulk Material PDFDocument8 paginiDust Prevention in Bulk Material PDFseptian bayuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Port Master Plan Presentation FIC102119Document37 paginiPort Master Plan Presentation FIC102119Vagner JoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inland Waterways and The Global Supply ChainDocument24 paginiInland Waterways and The Global Supply ChainBambang Setiawan MÎncă nu există evaluări

- Safe Port Issues in The Context of Chittagong Port - PPTDocument11 paginiSafe Port Issues in The Context of Chittagong Port - PPTmohiuddin_kadirÎncă nu există evaluări

- WG 212 MVT of ShipsDocument2 paginiWG 212 MVT of ShipsMaria XÎncă nu există evaluări

- Port Operations and Management: Dr. Funda Yercan, ProfessorDocument9 paginiPort Operations and Management: Dr. Funda Yercan, ProfessorCagatay alpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abdurezak MussemaDocument61 paginiAbdurezak MussemaIthan EstribiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transhipment - and - Cross - Docking (PGDSCLM 203 II)Document7 paginiTranshipment - and - Cross - Docking (PGDSCLM 203 II)Nandan SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter-2 - Chapter-3Document64 paginiChapter-2 - Chapter-3eepsitha bandayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Issues and Challenges of Logistics in Malaysia - With AbstractDocument11 paginiIssues and Challenges of Logistics in Malaysia - With AbstractVishyata0% (1)

- Copra, Coconut Products, Charcoal Market in India: Indonesian Trade Promotion Center (ITPC) Chennai 2021Document88 paginiCopra, Coconut Products, Charcoal Market in India: Indonesian Trade Promotion Center (ITPC) Chennai 2021Astra CloeÎncă nu există evaluări

- General Information On Massawa Port AuthorityDocument6 paginiGeneral Information On Massawa Port AuthorityAlfredLeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water Transportation Is The Intentional Movement by Water Over Large DistancesDocument3 paginiWater Transportation Is The Intentional Movement by Water Over Large Distancesmarvin fajardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Port of GeorgetownDocument10 paginiPort of GeorgetownTajae HarripersadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Đề Kiểm Tra Tiếng Anh 7 Global Success Có Key Unit 12Document18 paginiĐề Kiểm Tra Tiếng Anh 7 Global Success Có Key Unit 12Doan Bich NgocÎncă nu există evaluări