Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Drug Regulation in Several Countries

Încărcat de

mehdi2604Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Drug Regulation in Several Countries

Încărcat de

mehdi2604Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

GOOD REGULATORY SCIENCE IN ASIA/PACIFIC: PART 2

349

Emerging Markets and Emerging Agencies: A Comparative Study of How Key Regulatory Agencies in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa Are Developing Regulatory Processes and Review Models for New Medicinal Products

Neil McAuslane, BSc, MSc, PhD Director, CMR International Institute for Regulatory Science, United Kingdom Margaret Cone, BPharm, MRPharmS Director, Regulatory Publications, CMR International Institute for Regulatory Science, United Kingdom Jennifer Collins,* MA, BSc, MSc CMR Institute for Regulatory Science, United Kingdom Stuart Walker, BSc, PhD, MFPM, FRSC, FIBiol, FinstD, FRCPath Vice President and Founder, CMR International Institute for Regulatory Science, United Kingdom

An ongoing study has been set up by the CMR International Institute for Regulatory Science to record and analyze the regulatory procedures for the authorization of new medicines in 13 key countries, outside the ICH regions, where the pharmaceutical market is expanding or the regulatory agency plays an important role in regional development. These countries are Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, and Chinese Taipei. In the study, data were collected from senior personnel in the national agencies and from multinational pharmaceutical companies on the review and assessment processes for new active substances (NASs) and major line extensions (MLEs). The quality measures being applied by the agencies to monitor those proce-

dures were also recorded. The design of the study collected information for a status report at one time point, as summarized here, but also provides the basis for recording and benchmarking the progress and changes made by the agencies over time. A cross-comparison of information from the authorities indicated that regulatory aspirations, barriers, and priorities are essentially similar across agencies. The review steps are also similar although there are major differences in the assessment process. Most agencies are using risk stratification methods for their review of new medicines, based on the level of regulatory scrutiny the product has already undergone by agencies elsewhere. There is an awareness of the importance of building quality into agencies regulatory processes and practices and this is a changing and evolving area.

Key Words Regulatory review; Emerging markets; New medicines; Quality measures; Asia, Latin America, Middle East, and Africa Correspondence Address Dr. Neil McAuslane, CMR International Institute for Regulatory Science, The Johnson Building, 77 Hatton Gardens, London EC1N 8JS, United Kingdom (email: NMcAuslane@cmr.org). *Ms. Collins was formerly with CMR International Institute for Regulatory Science and is now with GlaxoSmithKline, Weybridge, Surrey, UK.

INTRODUCTION

When the regulatory review and approval of new medicines is studied at a global level, it is apparent that the division between the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) regions and the rest of the world is changing and is no longer so well defined. The CMR International Institute for Regulatory Science (hereafter the Institute) has been studying the regulation of medicines in some of the so-called emerging markets in order to benchmark and analyze these changes, particularly in relation to the availability of new medicines to patients in the countries studied. For the purposes of this study, the term emerging markets was used to encompass not only those countries with an expanding phar-

maceutical market, of increasing interest and importance to the pharma industry, but also those countries where it is the regulatory agency that is emerging. These countries are establishing regulatory procedures and practices that are likely to influence the development of agencies in neighboring countries within their regions and therefore to have an impact on product approval that extends beyond national boundaries.

BACKGROUND

Since 2004, the Institute has been working in association with the industry and agencies on an Emerging Markets Programme designed to develop a greater understanding of the regulatory aspirations, barriers, and priorities that impact the review and availability of new mediSubmitted for Publication: January 20, 2009 Accepted: February 15, 2009

Drug Information Journal, Vol. 43, pp. 349359, 2009 0092-8615/2009 Printed in the USA. All rights reserved. Copyright 2009 Drug Information Association, Inc.

350

GOOD REGULATORY SCIENCE IN ASIA/PACIFIC: PART 2

McAuslane, Cone, Collins, Walker

FIGURE 1

Phased approach to the study of regulatory procedures.

Phase I: Understanding the current environment 2004 Authority survey 24 countries 3 regions SE Asia Middle East & Africa Latin America Data on regulatory policies and practices Industry Survey 10 companies 30 countries

Phase II: Effecting change 2005-2006

Phase III: Maximizing efficiency and effectiveness 2006-2007 Authority survey 13 countries

Industry discussion meeting

Authority survey 13 countries

Industry discussion meeting

Industry discussion meeting

3 regional authority reports

3 regional industry reports

Country situation analyses highlighting priority issues

Country specific reports

Data on process plans target times quality procedures approval times Industry Survey 13 countries

Countryspecific reports

4 R&D Briefings

Report on industry data

cines in countries outside the ICH-affiliated regions (1).1 The study started with a broad-based fact-finding investigation of regulatory procedures in over 30 countries, but later it focused on issues in a smaller group of key countries where it was felt that changes could make a positive difference at national, and possibly regional, levels (see Figure 1). The third phase of the study, which is the subject of this article, covered 1 3 countries, including Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, and Chinese Taipei, in greater depth in terms of the type of assessment they undertake, the review models employed for the approval of new medicines, and how quality is built into the regulatory processes. Data were collected from regulatory agencies primarily through face-to-face meetings and from companies via a questionnaire. The quantitative data from the study enabled

comparisons of the regulatory performance of agencies in terms of timelines and identified apparent divergences between agency targets and industry experience. The more qualitative information on procedures, objectives, and quality management helped identify issues and activities that could impede or enhance the efficient and effective registration of medicines. A primary objective was to support arguments for regulatory reform and feed these back, as appropriate, to the agencies in order to help ongoing strategies to bring about change.

METHODOLOGY

DATA COLLECTION A questionnaire was used to collate comparative information (Figure 2) from the 1 3 authorities included in phase III of the study and, with the exception of China and India, the data were cap-

1. The primary regions of the ICH are the EU, US, and Japan. Affiliated countries are Canada and Switzerland (official observers to the ICH process), and other countries that have adopted the ICH guidelines are Australia and the European Economic Area countries Iceland, Lichtenstein, and Norway.

Regulatory Processes and Review in Emerging Markets

GOOD REGULATORY SCIENCE IN ASIA/PACIFIC: PART 2

351

Authority-level data

FIGURE 2

2007 Emerging Markets Programme data collection.

Drug registration on regulatory agency (eg, scope and remit) Type and size, fee structure and budget Type of data assessment Data requirements Extent of scientific review Review stages and milestones

Information

Clinical trial applications* Type of authorization procedure General model for review of CTAs Milestones and timelines Scientific assessment

Quality in the review measures in place Peer reviews, SOPs, GRP Quality management Internal tracking Training Transparency

Quality

*Subject of a subsequent, more detailed study in 2008

tured primarily through face-to-face meetings and interviews with senior agency staff. The questionnaires for China and India were completed using information from the public domain and with the assistance of experts with appropriate, first-hand knowledge of the national regulatory systems. Data were collected on the review procedures and approval of new active substances (NASs) and major line extensions (MLEs) submitted or approved from 2004 to 2006. After the data had been analyzed in the Institute, a second round of visits and meetings was organized in order to obtain further clarification and information, as necessary. The return visits also provided an opportunity to present and discuss cross-comparisons of review practices among the regulatory authorities included in the study. Data collection from industry sources was carried out using written questionnaires. Thirteen multinational research-based companies, which are actively registering and marketing products in all or most of the selected countries, participated in the study and they were asked to complete separate questionnaires for each market. As for the data collection from the authorities, the study was restricted to NASs and MLEs submitted and/or approved from 2004 to 2006.

SCOPE OF THE STUDY Key milestones in the review process were mapped (for both marketing and clinical trial applications) and information on these and related activities was collected from the authorities, including the quality measures that are being applied within their regulatory procedures. Metrics on numbers and timing for NAS and MLE applications for 20042006 were among the data that were sought for the study. The data collected from participating companies fell into two categories: Product-related metrics from their own marketing and clinical trial applications; and industry perceptions of the activities carried out at authority level (eg, target review times and procedures for handling clinical trial applications). ANALYSIS All data relating to individual products have been aggregated and anonymized for confidentiality reasons. Metrics on the time taken to review and approve applications were converted to calendar days for uniformity and calculated as medians. Since the variation of results about the median, within the same authority, was an important element for comparative purposes, a box and whisker layout was used to present the

Drug Information Journal

352

GOOD REGULATORY SCIENCE IN ASIA/PACIFIC: PART 2

McAuslane, Cone, Collins, Walker

FIGURE 3

Regulatory approval times from date of submission to date of approval for NASs approved between 2004 and 2006 (company data). Time (days)

2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0

) ,8) ,8) ,4) ) ) ) ) ,3) )

Regional Medians Latin America = 179 Middle East and Africa = 671 Asia Pacific = 292 Overall median for all authorities = 290

) 3,8 (1 se Tai p ei

,9)

0,9

8,3

5,7

0,6

2,6

1,5

23

19

(9

(7

23

(2

t(

(1

(1

(1

(1

il (

o(

ica

ia

a(

yp

sia

na

ia

Afr

Eg

Ind

xic

az

rab

esi

nti

Ch

lay

po

Me

on

ge

uth

iA

Ma

ga

Ind

ud

So

Sin

uth

Ar

Sa

So

Authority Data are shown for NASs that were approved between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2006. (n1) = number of drug applications, (n2) = number of companies providing data. Box: 25th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers 5th and 95th percentiles. Diamond = median.

results (see Figure 3) in which the box represents the 25th75th percentile and the whiskers the 5th95th percentile.

R E S U LT S A N D D I S C U S S I O N

APPROVAL TIMES AND TIME TO MARKET When the median approval times for NASs, calculated from data supplied by the 1 3 participating companies, are compared for 20042006, they vary widely around an overall median of 290 calendar days, from 127 days (Argentina) to 1,388 days (Egypt). (Figure 3). The approval time is not, however, the only factor to have an impact on the rollout time that it takes for new medicines to reach the different markets compared with first approval anywhere, usually in an ICH country (Figure 4). There is a critical time interval between approval by the first authority and subsequent submission for approval in another market. For the countries studied, this ranged from minimal or no time elapsing in some Latin American countries to delays of over a year. The main components affecting the delay in

submitting an application are national application requirements (eg, the need for a CPP [Certificate of a Pharmaceutical Product],2 requirements for local clinical trials) and company strategy in selecting priority markets. The differing national approval times are then related to the type of review carried out by the agency. One of the objectives of the institute study was to provide a better insight into these factors. TYPES OF ASSESSMENT One of the recommendations to emerge from the early phases of the emerging markets study and related workshops (2,3) was that All parties would benefit from a much greater openness in accepting that most agencies do not have the resources and skills to carry out a full review of new active substance (NAS) applications and that there should be greater clarity in defining the review process that is actually followed. To this end, assessment types were classified as Type 1, verification; Type 2, abridged; and Type 3, full (see Table 1).

2. CPP issued under the WHO Certification Scheme for the Quality of Products Moving in International Commerce, http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/regulation_legislation/certification/en/index.html.

Ch

ine

Ko

Br

rea

ina

re

(1

3,8

Regulatory Processes and Review in Emerging Markets

GOOD REGULATORY SCIENCE IN ASIA/PACIFIC: PART 2

353

Argentina Brazil Mexico Egypt Regulatory Authority Saudia Arabia South Africa China India Indonesia Malaysia Singapore South Korea Chinese Taipei 0 250 500 750 1000 1250 1500 1750 2000 2250 2500 Median approval time in first market Median gap: First market approval EM submisssion Median EM country approval time

FIGURE 4

Comparative median rollout times for NASs in different markets. EM, emerging markets.

Median time intervals: First market submission to EM market approval (days)

This classification was used to compare the assessment models used by the different agencies. The results showed that more than one type of assessment is used by the agencies in some countries when all types of application are considered. When the assessment predominantly of NAS and MLE applications is considered, however, this picture emerged:

Argentina was the only country routinely using a Type 1 assessment for major applications. Mexico, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, and Singapore generally used assessment Type 2 for most products. Brazil, South Africa, China, India, Indonesia, South Korea, and Chinese Taipei routinely apply a full assessment (Type 3) process to NAS applications but this is only completely self-standing in South Africa as the other countries still require evidence of approval in a reference country before a final authorization for local marketing can be issued.

EVIDENCE OF AUTHORIZATION ELSEWHERE A cornerstone of assessment Types 1 and 2 is that there should be evidence that the prod-

uct is registered elsewhere. The CPP remains the most common means of verifying this but timing and requirements vary. The CPP is required at the time of submission by Argentina, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia, but in Brazil and most of the Asia-Pacific countries studied it can be submitted after the application but before authorization. The need for legalization of the CPP through an embassy or consulate in the exporting country remains a requirement in Brazil, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Chinese Taipei and has been identified, by industry, as one of the factors that impede rapid and efficient rollout of new medicines to new markets. As noted, most countries that follow Type 3 procedures still prefer the safety net of not being the first agency to register an NAS. The CPP is not required in South Africa and both Singapore and Indonesia can carry out a full review without prior authorization elsewhere but, when such evidence is required, there is some flexibility and evidence other than the CPP can be accepted.

Drug Information Journal

354

GOOD REGULATORY SCIENCE IN ASIA/PACIFIC: PART 2

McAuslane, Cone, Collins, Walker

Types of Data Assessment

TABLE 1

Type 1: Verification Assessment This model avoids duplicating the assessment of a new product that is identical to one which has been approved elsewhere. The elements are: Recognition of an authorization by one or more reference or benchmark agencies. A verification process to validate the status of the product and ensure that the product for local marketing conforms to the authorized product. Type 2: Abridged Assessment This model also conserves resources by not reassessing the full scientific supporting data but focuses on aspects that must be evaluated specifically for the local environment. It is a prerequisite that the product has been registered by a reference or benchmark agency. An abridged assessment is carried out in relation to the use of the product under local conditions (eg, focusing on aspects of quality such as stability and on a benefit-risk assessment for the local medical practice/culture and patterns of disease). Type 3: Full Assessment In this model the agency has suitable resources, including access to appropriate internal and external experts, to carry out a full review and evaluation of the supporting scientific data. A full, independent review of quality, preclinical (safety), and clinical (efficacy) data is carried out. Information on registrations elsewhere (if any) is taken into consideration but is not a prerequisite to filing or for authorization.*

* In practice, prior authorization was a legal requirement in some countries, before local authorization could be finalized, but filing the application and the review was not delayed.

REVIEW PROCESS MODELS The basic process map that is common to almost all agencies in both ICH-affiliated regions and the emerging markets consists of the following elements: Validation Scientific Assessment Questions to Sponsor Final Report Approval Procedure This sequence was used to construct a generic model to map the stages in the review process (see Figure 5). The model also indicates the different stages at which timing might be recorded to allow targets and timelines to be set. Agencies were asked questions about their procedures, based on this model, and individual processes were mapped accordingly. Some of the most noticeable differences that were found among agencies were in the procedures and the sequence for referring the application to outside experts or committees. Other differences were found in the timing of questions to the sponsor and in whether the different sections of the application (safety, quality, and efficacy) were assessed in parallel or in sequence.

Although an overall similarity between countries and regions was found, there are, as noted in Figure 5, key areas where notable differences were found between processes. Mexico, for example, has introduced a voluntary preapplication procedure that allows companies the opportunity to discuss NAS applications with a committee of experts prior to submission. In China, a full IND and clinical development program must be undertaken in the country before an application for marketing can be made. Queue times can vary widely with applications being picked up for review almost immediately in some countries (eg, Chinese Taipei and South Korea) or waiting six months to a year in others. The classic review sequence is to carry out a parallel review with the quality, safety, and efficacy sections of the application being assessed at the same time. Examples of a sequential review were, however, reported from Indonesia, where safety and efficacy must be approved by the expert committee before resources are assigned to the quality section and in Mexico where quality is assessed before the review of safety and efficacy commences.

Regulatory Processes and Review in Emerging Markets

GOOD REGULATORY SCIENCE IN ASIA/PACIFIC: PART 2

355

Preapplication procedure A B Milestone recorded Date application received Receipt and validation procedures Accepted for review Milestone recorded Queuing for review C Scientific review starts Quality Safety Efficacy Scientific Assessment D E1 Questions to sponsor Timing recorded Questions processed by sponsor Reply from sponsor Timing recorded Scientific Assessment continues F G Start of Committee procedure Committee Procedure Opinion received Final report H Scientific assessment ends Milestone recorded

Admi n time xx days 2

Valid ation time xx Admi n time Xx 1

days

days

Milestone recorded Reviewed in parallel

Ass ess men t time 1

xx days

Xx days

Key areas where the review process can differ: Preapplication requirements and validation process Queue time and whether there is a backlong. Scientific assessment and how the scientific review is conducted: Parallel vs. sequential assessment of safety, quality, and efficacy Use of advisory committees Available resources and use of external experts Questions to sponsors: timing, time limit to respond, batching of questions, and interaction with the sponsor Authorization Additional criteria for the decisions on applications (eg, Pricing, Sample Analysis) Responsibility for the final decision

FIGURE 5

Review process: generic model.

xx days

Approval procedure Approval granted Milestone recorded

Procedures for the final authorization process differ and can cause delays if matters other than the scientific review need to be finalized before the authorization is issued. Three authorities Brazil, Egypt, and Saudi Arabiarequire pricing agreements before authorization and sample analysis is required in Egypt and Saudi Arabia and for certain biologicals in Brazil and Mexico. TARGETS Agencies were asked, with reference to the process map, about the stages for which targets and deadlines are set. Although these are important in making the review more predictable and project management more efficient, not all agencies had documented targets. For validation, the targets ranged from none to less than five weeks, for scientific assessment from none to 160 calendar days, and for the authorization procedure from none to one month. Targets for overall approval times ranged from none to a

year and different targets applied in countries (eg, Singapore) where different assessment routes could be followed. A comparative summary of the target times for the different stages of the review for countries in Asia is given in Table 2.

PERCEPTIONS OF REVIEW PROCEDURES

Both agencies and industry were asked for their viewpoint on factors that contribute to and those that impede the effectiveness and efficiency of the review. The positive factors were: political will; adequate resources; training (and retaining) qualified and experienced staff; electronic tracking systems; and standardization of the review process through good regulatory review practices (GRP) and standard operating procedures (SOPs). Complete submissions from industry are also a major contribution to the process.

Drug Information Journal

356

GOOD REGULATORY SCIENCE IN ASIA/PACIFIC: PART 2

McAuslane, Cone, Collins, Walker

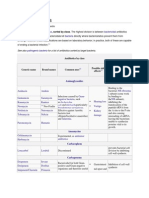

Target Times and Features of the Review Process for Countries in Asia for 2007 (Authority Data)

TABLE 2

Target in Working (wkd) or Calendar (cd) Days AuthorScientific ization Validation Assessment Procedure 90 wkd 13 months (standard) 80 wkd (special approval) X X X <1 month Overall Approval Time 175195 wkd Primary Scientific Assessment InterReview Review nal or Parallel by by Use of Exteror Agency External External nal Sequential Staff Staff Experts Int Parallel QSE Ad hoc Expert opinion

Country China*

India Indonesia

2 wkd

6 months P1 = 100 wkd P2 = 150 wkd P3 = 300 wkd NAS <7 months T1 = 90 or 60 wkd T2 = 180 wkd T3 = 270 wkd 85 wkd

Int Int and Ext Int and Ext Int

Parallel Sequential

QSE QSE

Ad hoc Ad hoc

Not given Clinical opinion Clinical opinion Clinical opinion Advice on technical issues Clinical opinion

Malaysia

<5 weeks

14 cd

<1 month

Parallel

QSE

S&E

Singapore

21 wkd

Parallel

QSE

S&E

South Korea

N/A

60 wkd

25 wkd

Int

Parallel

QSE

Ad hoc

Chinese Taipei

N/A

160 cd (no CPP) 100 cd (with CPP)

13 months

380 cd with CPP 440 without CPP

Int

Parallel

QSE

Ad hoc

P1, P2, P3 = different assessment routes for Indonesia; T1, T2, T3 = different assessment routes for Singapore; QSE = quality, safety, and efficacy data.

In practice, of course, for every positive factor that helps the review there is an opposite negative factor that might impede the process. Pharmaceutical companies observations on review processes fell into four areas:

Evidence of registration elsewhere needs to be rationalized and the timing and requirements for the CPP continue to cause concern. Transparency and communication during the review process are perceived as important benefits, as are targets and optional procedures (as in Singapore). Data requirements should be within international norms (ie, ICH guidelines for new medicines) and other issues such as pricing and site inspections should be separated from the scientific review process.

The organization of the agency should be adequately resourced and operate with as much flexibility and as little bureaucracy as possible.

QUALITY OF THE REVIEW

The study looked at how the authorities are periodically evaluating quality in the review process and the activities being undertaken to improve communication and transparency of decision making, as well as the main factors that are driving authorities to improve quality. Quality is a notoriously difficult concept to define, but an earlier and ongoing study among established regulatory agencies (4) has identified eight key measures that are essential for GRP.3 In the Institute study on emerging markets, these

3. The CMR International Institute Benchmarking Study, initiated in 1998, collects data on the regulatory review processes in the US, EU, Canada, Australia, and Switzerland.

Regulatory Processes and Review in Emerging Markets

GOOD REGULATORY SCIENCE IN ASIA/PACIFIC: PART 2

357

dddd

Components of a Quality Review 6. Continual improvement activities: conducting internal quality audits, self-assessments, analyses of feedback from stakeholders, postapproval analysis with other authorities and industry, management reviews, and using the results to take corrective action or introduce improvements to the review process and decision making. 7. An established setup and process that allows regular contact with industry: for example, to discuss development and review plans, clarify statutory requirements, provide scientific and regulatory advice, inform the applicant on how the review is progressing, and develop partnerships and synergies between the two parties. 8. A transparent system that provides important review information to the public: for example, open public hearings of advisory committee meetings, or the publication of the summary basis of approval and assessments following approval.

1. Key quality documentation: regularly updated and comprehensive quality policies, standard operating procedures, and assessment templates. 2. Professional development of assessors and retaining of staff: adequate incentives to competent staff and regular training of assessors that focuses on improved practices; scientific and technological advancements; knowledge and skills transfer. 3. Built-in quality controls such as systematic management checks, structured approach to decision making, and robust internal tracking systems. 4. Internal reviews: a structured and integrated peer review system, as well as expert reviews by independent advisory committees. 5. Benchmarking and key performance indicators such as regular use of quantitative indicators on processing times; response times; frequency and number of withdrawals; as well as the carrying out of benchmarking exercises that compare processes or outcomes.

TABLE 3

eight components of a quality review were defined, as set out in Table 3, and were used as the baseline for obtaining comparative data from the agencies in the study. MOTIVATION When 1 1 agencies were given a list of seven possible reasons for introducing quality measures and asked to select the three most important, the first selection was to ensure consistency (10/ 1 1), the second to ensure efficiency (8/1 1), and the third to minimize errors (6/1 1). QUALITY MEASURES IN PLACE Agencies were given a list of quality measures and asked whether they were currently implemented or planned for the near future. It was noted that the agencies are at different stages of development and also that they were undergoing rapid change, even in the two years since the study was initiated. Looking at the overall approach to quality management, eight authorities (Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea, and Chinese Taipei) had, at the time of

the study, an internal quality policy. Indonesia, South Korea, and Chinese Taipei had a member of staff responsible for the development of quality and good review practices and four (Argentina, Brazil, India, and Malaysia) stated that they had a department for assessing and ensuring quality, but there are differences in the structure and resources allocated to these internal units. With respect to quality documentation, 10 authorities use SOPs for the guidance of scientific assessors: Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, and Chinese Taipei. Eight authorities use assessment templates for reports on the scientific review of a new active substance: Argentina, Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, and Chinese Taipei. These templates set out the content and format of written reports on scientific reviews. Egypt and Saudi Arabia indicated that they intended to introduce both SOP and assessment templates within the next two years. Four authorities (Indonesia, Mexico, South Korea, and Chinese Taipei) indicated that they

Drug Information Journal

358

GOOD REGULATORY SCIENCE IN ASIA/PACIFIC: PART 2

McAuslane, Cone, Collins, Walker

have implemented a GRP system and Malaysia has all the components of such a system. There can, however, be considerable differences in the extent of development of these systems. Argentina, Egypt, Singapore, and South Africa reported that they planned to introduce a GRP system in the near future. Continuous improvement measures included collecting feedback from stakeholders following a review, which is carried out by all 1 1 agencies studied, and reviewing feedback from the assessors themselves (10 agencies). Ten agencies had internal tracking systems to monitor applications and review progress and eight reported that they had formal training programs. External quality audits were relatively infrequent (3/10), and internal audits were even more infrequent (3/1 1). COMMUNICATION, TRANSPARENCY, OPENNESS Companies place great emphasis on the advantages of working with an agency that operates in an open and transparent manner, but there is a perception among authorities that transparency does not always work both ways and that companies can be criticized for poor communication and lack of transparency.

When asked about their general perceptions of the need for transparency, 8 out of 10 agencies that responded assigned a high priority to being open and transparent. (Information was not available from Brazil, China, and India.) In relation to the specific benefits to be attained, 9 out of 10 agreed that it increased confidence in the system, 8 felt that it helped provide assurances on safety safeguards, and 6 believed it led to better staff morale and performance. Some of the specific attributes used as a measure of transparency are shown in Figure 6. There was general agreement that authorities can enhance their standing with the public, health professionals, and industry by allocating time and resources to provide information on their activities and decisions in an open and transparent manner.

SUMMARY

QUALITY MEASURES Most authorities in the countries studied have a range of quality systems and measures but they are at different stages in their development and maturity. The smallest number of implemented measures was found in the Middle East countries in the study (Saudi Arabia and Egypt).

FIGURE 6

Communication and transparency in the regulatory review process.

Attribute Industry can track progress of applications Official guidelines to assist industry Presubmission scientific advice to industry Details of technical staff to contact Feedback to industry on submitted dossiers 0 2 3 4 6 Number of authorities 8 10 6 9 11 11

Regulatory Processes and Review in Emerging Markets

GOOD REGULATORY SCIENCE IN ASIA/PACIFIC: PART 2

359

CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT INITIATIVES Many agencies have focused on improving their assessment of feedback from stakeholders and reviewers as well as establishing tracking systems, although few have either internal or external quality audits. GOOD REGULATORY REVIEW PRACTICE The importance of establishing and implementing a GRP system is well understood although few agencies have achieved this to date. Several, however, are planning this within the next two years, although the level of detail and value has yet to be assessed.

Regulatory authorities are aware of the importance of building quality into their regulatory processes and practices, although there are currently differences in the way in which quality measures are being applied.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank both the companies and agencies that gave their time and provided information that made this study possible.

REFERENCES

1. McAuslane N, Cone M, Collins J. A cross regional comparison of the regulatory environment in emerging markets. CMR International Institute for Regulatory Science R&D Briefing No. 50, February 2006. Available at: http://www.cmr.org/ institute/PDF/RD50.PDF. Walker S, Cone M, Collins J. The emerging markets: regulatory issues and the impact on patients access to medicines. CMR International Institute for Regulatory Science Workshop Report, April 2006. Available from Institute@ cmr.org. Walker S, McAuslane N, Cone M, Collins J. Emerging markets: models of best practice for the regulatory review of new medicines. CMR International Institute for Regulatory Science Workshop Report, March 2008. Available from Institute@cmr.org. Cone M, McAuslane N. Building quality into regulatory activities: what does it mean? CMR International Institute for Regulatory Science R&D Briefing No. 46, June 2006. Available at: http:// www.cmr.org/institute/PDF/RD46.PDF.

OVERALL CONCLUSIONS FROM THE STUDY

The regulatory aspirations, barriers, and priorities are essentially similar across agencies. The review steps are also similar although there are major differences in the assessment process. Regulatory review procedures and requirements are undergoing rapid change in the 1 3 countries studied and both authorities and companies are seeking to understand better the factors that impact on performance. Most agencies are using risk stratification methods for their review of new medicines, based on the level of regulatory scrutiny the product has already undergone elsewhere. The challenge is how best to evolve these methods to ensure timely access of patients to new medicines within an appropriate benefit/risk decision-making process.

2.

3.

4.

All authors at the time of this study were employees of CMR International Institute for Regulatory Science, which is funded by unrestricted membership dues from biopharmaceutical companies. The authors declare no competing interests.

Drug Information Journal

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- SRS Statistical Report 2018Document359 paginiSRS Statistical Report 2018mehdi2604Încă nu există evaluări

- TermsofReference XVFCDocument3 paginiTermsofReference XVFCPreetesh KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tuning In, Turning Outward: Cultivating Compassionate Leadership in A CrisisDocument7 paginiTuning In, Turning Outward: Cultivating Compassionate Leadership in A CrisisAasrith KandulaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wilayat in The Quran - Jawadi AmuliDocument222 paginiWilayat in The Quran - Jawadi Amulimehdi2604Încă nu există evaluări

- TermsofReference XVFCDocument3 paginiTermsofReference XVFCPreetesh KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revised Guidelines On AES - JEDocument30 paginiRevised Guidelines On AES - JEegalivanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Wage Report 2014 - 15Document132 paginiGlobal Wage Report 2014 - 15Claudiu Marius RÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 13 Economic Survey ReportDocument25 paginiChapter 13 Economic Survey ReportSurendra Pratap SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- McKinsey - Why Pharma Megamergers WorkDocument5 paginiMcKinsey - Why Pharma Megamergers Workmehdi2604Încă nu există evaluări

- WHO - Health Inequality MonitoringDocument126 paginiWHO - Health Inequality Monitoringmehdi2604100% (1)

- The Politics of Poverty: Citizens, Elites and States - DFIDDocument104 paginiThe Politics of Poverty: Citizens, Elites and States - DFIDVictor Zamora MesíaÎncă nu există evaluări

- McKinsey - Why Pharma Megamergers WorkDocument5 paginiMcKinsey - Why Pharma Megamergers Workmehdi2604Încă nu există evaluări

- Handbook of Action ResearchDocument19 paginiHandbook of Action Researchmehdi26040% (1)

- IslamicDocument14 paginiIslamicMolai2010100% (1)

- Arundhati Roy - I'd Rather Not Be AnnaDocument5 paginiArundhati Roy - I'd Rather Not Be Annamehdi2604Încă nu există evaluări

- Decentralization and Health OutcomesDocument28 paginiDecentralization and Health Outcomesmehdi2604Încă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Automatic Stop Orders (ASO)Document3 paginiAutomatic Stop Orders (ASO)Bae BeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bài tập tiếng anhDocument8 paginiBài tập tiếng anhLinh KhánhÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Shelters in The Lower Mainland, June 2007Document2 paginiList of Shelters in The Lower Mainland, June 2007Union Gospel Mission100% (1)

- Self, IdentityDocument32 paginiSelf, IdentityJohnpaul Maranan de Guzman100% (2)

- Advert MBCHB Bds 2014 Applicants3Document9 paginiAdvert MBCHB Bds 2014 Applicants3psiziba6702Încă nu există evaluări

- Anatomy of The Male Reproductive SystemDocument70 paginiAnatomy of The Male Reproductive SystemDaniel HikaÎncă nu există evaluări

- HR Director VPHR CHRO Employee Relations in San Diego CA Resume Milton GreenDocument2 paginiHR Director VPHR CHRO Employee Relations in San Diego CA Resume Milton GreenMiltonGreenÎncă nu există evaluări

- COVID-19: Vaccine Management SolutionDocument7 paginiCOVID-19: Vaccine Management Solutionhussein99Încă nu există evaluări

- Herba ThymiDocument9 paginiHerba ThymiDestiny Vian DianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Errors of Eye Refraction and HomoeopathyDocument11 paginiErrors of Eye Refraction and HomoeopathyDr. Rajneesh Kumar Sharma MD HomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child Abuse Nursing Care PlanDocument7 paginiChild Abuse Nursing Care PlanMAHESH KOUJALAGIÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of AntibioticsDocument9 paginiList of Antibioticsdesi_mÎncă nu există evaluări

- RobsurgDocument34 paginiRobsurghotviruÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review Ct-GuidingDocument10 paginiReview Ct-GuidingHeru SigitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hepatitis B Virus Transmissions Associated With ADocument9 paginiHepatitis B Virus Transmissions Associated With AAyesha Nasir KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Block Learning Guide (BLG) : Block II Hematoimmunology System (HIS)Document6 paginiBlock Learning Guide (BLG) : Block II Hematoimmunology System (HIS)ASTAGINA NAURAHÎncă nu există evaluări

- Britannia Industry LTD in India: Eat Healthy Think BetterDocument12 paginiBritannia Industry LTD in India: Eat Healthy Think BetterMayank ParasharÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACTIVITY DESIGN-first AidDocument4 paginiACTIVITY DESIGN-first AidShyr R Palm0% (1)

- Perdev Week 5Document3 paginiPerdev Week 5AdiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- API 580 SG Part 1, Rev 4Document77 paginiAPI 580 SG Part 1, Rev 4Mukesh100% (8)

- Postpartum Depression in Primigravida WomenDocument22 paginiPostpartum Depression in Primigravida WomenMrs RehanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient Transportation ProtocolDocument8 paginiPatient Transportation Protocolsami ketemaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (SAMPLE THESIS) Research and Analysis Project (Obu)Document66 pagini(SAMPLE THESIS) Research and Analysis Project (Obu)Murtaza Mansoor77% (35)

- Telescopium) EXTRACTS: West Visayas State University College of MedicineDocument5 paginiTelescopium) EXTRACTS: West Visayas State University College of MedicineMark FuerteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reimplantation of Avulsed Tooth - A Case StudyDocument3 paginiReimplantation of Avulsed Tooth - A Case Studyrahul sharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 6 Test Skeletal SystemDocument49 paginiChapter 6 Test Skeletal SystemAlexandra CampeanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reszon Pi - Typhidot Rapid Igm 2011-01Document2 paginiReszon Pi - Typhidot Rapid Igm 2011-01Harnadi WonogiriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aldinga Bay's Coastal Views April 2014Document48 paginiAldinga Bay's Coastal Views April 2014Aldinga BayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Professional AdvancementDocument51 paginiProfessional AdvancementReshma AnilkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- GRP 3 - Galatians - Borgia Et1Document3 paginiGRP 3 - Galatians - Borgia Et1Kyle BARRIOSÎncă nu există evaluări