Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Sacred Groves of The Balts: Lost History and Modern Research

Încărcat de

annca7Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Sacred Groves of The Balts: Lost History and Modern Research

Încărcat de

annca7Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

doi:10.7592/FEJF2009.42.

vaitkevicius

THE SACRED GROVES OF THE BALTS: LOST HISTORY AND MODERN RESEARCH

Vykintas Vaitkevi ius

Abstract: The article deals with the sacred groves of the Balts in Lithuania and presents the linguistic background, the historical documents from the 12th 18th century, the key folklore motifs of the topic, as well as selected examples of groves. The article also discusses possible relationships between pre-Christian religious traditions connected with the sacred groves and the ones which have survived into the 21st century. Despite the fact that the sacred groves of past ages have mostly disappeared on the landscape, this tradition has not significantly changed. Various religious activities which were carried out in sacred groves, at smaller groups of trees, and beneath separate trees enable us to learn, even if insignificantly, about the phenomenon. Interdisciplinary approach to sacred groves should be preferred in modern research. Key words: Lithuania, natural holy places, sacred groves, sacred trees, the Balts

INTRODUCTION Sacred grove was a universal type of natural holy places in the ancient world. It was prevalent among the Balts in prehistoric and also historic times. However, researchers are in sad lack of special knowledge while examining culture that is based on oral tradition. The materials to be used in research are often scattered, indeterminate, and unattractive in academic terms. The list of previous works on the sacred groves of the Balts is rather short. National as well as international audience needs more comprehensive materials and explanation. The most remarkable progenitor in this field is the Latvian archaeologist Eduards turms. His study Die Alksttten in Litauen (1946), in which the main outlines for further investigations were drawn, is still relevant. Furthermore, the study presents a list of natural holy places, including the sacred groves.1 In later years only some references were made (cf. turms 1948; Wenskus 1968; Urtns 1989) and now, after a long pause, the study of the sacred groves of the Balts has been undertaken again (Vaitkeviius 2004: 16ff).

Folklore 42

http://www.folklore.ee/folklore/vol42/vaitkevicius.pdf 81

Vykintas Vaitkevi ius

General studies into the so-called tree worship provide us with some references to the sacred groves mentioned in written sources (cf. Ivinskis 1938/ 1986; Balys 1966: 62ff; Dundulien 1979) and these are used to illustrate all theoretical theses on the subject. However, a grove differs from a stone or hill in terms of its existence which should be specified in many ways as temporary. This specific feature of the groves as well as its changing size and outside appearance, has not yet enabled researchers to present final conclusions. The questions concerning the religious and social role of the sacred groves in preChristian religion have remained open so far. There are some more important aspects to mention: namely, gods associated with trees, a trees gender in the Lithuanian folk worldview system, and relationships between tree and man depending on the age of the latter (which changed with respect to ones social status). The example of oak and lime tree is perfectly well known among mythologists and folklorists these trees represent the god of thunder (Lith. Perk nas, Lat. Prkons) and the goddess of fortune (Lith. and Lat. Laima), respectively. However, this is not the only example. The famous tale Egl the Queen of Grass Snakes (AT 425M) has been recorded in numerous versions in both Lithuania and Latvia. At the centre of this tale there is a mother called Egl, who turned into a fir tree, her three sons turned into an oak, a birch and an ash, and her daughter became an aspen. Egls husband was believed to be a grass snake called ilvinas (cf. Lith. ilvytis osier) (further on this topic see Martinkus 1989). Despite all exertions by researchers to reveal the specific meaning of this mythological narration, it is still shrouded in mist.

LINGUISTIC BACKGROUND Sacred groves are the central subject of this article. Here, linguistics provides some essential details to support the research. There are words alka (fem.) and alkas (masc.) which have the meaning of a sacred grove, a place where sacrifices were burnt, and sacrifice in the Lithuanian language (Balikonis 1941: 84), and elks or idol in Latvian (Karulis 1992: 264). Next to Lithuanian gojus small, beautiful grove and Lithuanian ventas, the Latvian sv ts holy quite often appears as equivalent for alka(-s) and elks. The terms alka(-s) and elks are the most commonly used names (sometimes elements of compound place names) which mark natural holy places of different types in Lithuania and Latvia, thereby indicating the close ties between sacred groves on the one hand and hills, fields, and water bodies, on the other (120 Alka hills, 70 Alka fields, 50 Alka lakes, rivers, and wetlands have been registered in Lithuania

82

www.folklore.ee/folklore

The Sacred Groves of the Balts: Lost History and Modern Research

and Latvia). There are some other examples: historically attested proper names of the sacred groves sometimes correspond to the names of rivers located in the same, or approximately the same, region (cf. place names Asswyiote and Avija). It seems reasonable to assume that the sphere of the sacredness of the Baltic gods and/or deities used to entail more than only one grove: it was spread over a particular geographical area, including various sites and objects like rivers, lakes, and hills (for example, potential cult sites). Some available data is rather fragmentary. The number and significance of the sacred groves have diminished over the last 600 years. In this situation it is practical to register and examine the remnants of sacred woodland areas rather than the actually extant pre-Christian cult sites.

EVALUATION OF HISTORICAL SOURCES Adam of Bremen was the first to mention the sacred groves of the Baltic tribes, while talking about Prussians in c. 1075. According to him, the entrance to the sacred groves and springs was inaccessible for Christians to avoid the pollution of a particular holy place (solus prohibetur accessus lucorum et fontium, quos autumant pollui christianorum accessu) (Vlius 1996: 190ff). Very likely the note is connected with the Sambian Peninsula. In the 14th-century documents, left by members of the Teutonic Order, a few sacred groves are mentioned to have existed in the above region (e.g., sacra sylva, que Scayte vulgariter nominatur..., silva, quae dicitur Heyligewalt...) (Vlius 1996: 319ff). Historian Reinhard Wenskus (1968: 322) has determined that sacred groves covering relatively small areas on the Sambian Peninsula have separated one village from another. In the 14th15th century, sacred groves became the focus of the Teutonic Order in Samogitia (the western part of modern Lithuania). Though described in geographical terms, sacred groves were mentioned in documents only as well-known landmarks (e.g., von deme heyligen walde von Rambyn..., II mile bis cz Saten cz deme heiligenwalde...) (Vlius 1996: 429ff). Authors of the same period from Poland, Czechia, and other countries have described tree and sacred grove worship as a general but important phenomenon, characteristic of pagans (cf. Historia Polonica, Vlius 1996: 556ff). A number of 16th-century documents, including detailed descriptions of land and property (sometimes also accompanied by drawings), are stored in the Lithuanian archives. These facilitate updating the database of the sacred groves with geographically precisely localized material; however, this data still needs investigation.

Folklore 42

83

Vykintas Vaitkevi ius

In the second half of the 16th century, the first reports by Jesuit missionaries emerged. Together with other traces of paganism (e.g., fire worship), sacred groves are described in these reports often enough. These descriptions, dated to the early 17th century, are unique in many respects although they lack detailed localization of the observed subjects (cf. Vlius 2001: 618ff). It is characteristic of the latter period that similar sources on the Baltic people (also partly Germanized) are available from the neighbouring Livonia and Eastern Prussia. Owing to the remarkable accuracy of the descriptions of rituals and mythological imaginations, the manuscript Deliciae Prussicae, oder Preussische Schaubhne by Matthaeus Praetorius (c. 16351704) is of particular interest. A pastor by profession, Praetorius was historian and ethnographer all his life. His main research subject was Old Prussians and Lithuanians living within the territory of Eastern Prussia. Praetorius has written an 18-volume manuscript on the history of Prussia. In three volumes (vols. 4, 5, and 6) he refers to religious customs, beliefs, and festivals associated with various spheres of the private and public life (Lukait 2006). Materials recorded by Praetorius are often unique and versatile sources for research. He also presented some remarkable drawings (Fig. 1). Praetorius work provides important evidence in the form of narration: especially one narration tells about how a particular tree could be turned into a sacred tree. For this purpose, a person (who was usually called vaidutis priest), a member of the preChristian priesthood, summoned the God to the tree. During this ceremony, which lasted for three days, the priest went on a fast. If nothing happened, the priest needed some blood (of his own or childrens) to stain the treetrunk with it. After this act (which Praetorius has called, very likely under the influence of Christian terminology, consecration), sacrifice was made and a festival was held near Figure 1 . Die Eiche im Ragnitischen the sacred tree. Felde (Oak on the Ragnit Field). Drawn When talking about the 18th century, by Matthaeus Praetorius before 1699 a huge amount of descriptions of land and (Lukait 2006: 118119). An ill person is climbing up an oak tree to a special property has to be taken into account. hole, through which a piece of cloth has There are also some original (or at least been tied.

84

www.folklore.ee/folklore

The Sacred Groves of the Balts: Lost History and Modern Research

partly original) works which deal with the ancient sacred groves and remnants of pre-Christian religion in the then culture. The 19th-century authors (Narbutt, Daukantas, and others) who tried to become researchers rather than being passive observers added importance to the discussed topic. In sum, historical sources are rich in particular details concerning sacred groves. The data is highly valuable, although it generally lacks precise geographical information. Only 13 forests and groves have been mentioned in the 14th- to 17th-century sources altogether; the location of these 13 could be determined, at least approximately (Vaitkeviius 2004: 17). Although in historical sources (see Vlius 1996: 595ff) the central part of the sacred groves has sometimes been regarded as a residence of the gods, its location cannot be determined today. The sacred groves have been often turned into fields or can be traced only in place names on the landscape. A telling example is the groves called Gojus, which are mentioned in 17th- and 18th-century historical sources in huge numbers. By the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, these had already mostly become cultivated fields and meadows. While it is truly fortunate that a sacred grove mentioned in historical sources can be identified as a present-day grove, at the same time one should be content with the very idea about the sacred grove as a sacred space in general and in terms of some already lost details. Beasts and birds living in the sacred grove were distinguished by having a special status and religious ceremonies held in the sacred groves were inspired by conceptions about the gods and the dead. Of course it was strictly forbidden to break a branch or cut a tree in the grove: Heyligwald [= sacred grove] [...], beautiful trees grow there, tall birch trees and junipers underneath. Samogitians still believe it to be sacred; it is forbidden to cut trees there so that the gods that live in the wood would not be injured. (Vlius 2001: 326, 339)2 Special attention should be given to the presence of East-Lithuanian barrow groups (which are characteristic of the 5th12th century and contain mainly cremation burials) in the Gojus groves. Such links between burials and areas of sacred groves allows a reasonable presumption that sacred groves have functioned as cultic places, although a precise description of the latter remains a subject for special study. IMPORTANCE OF FOLKLORE Despite the fact that real, or academically acceptable history does exist in written form while folklore exists in oral, they are not alternative from the viewpoint of the present study. Tales, legends, and beliefs often serve as ex-

Folklore 42

85

Vykintas Vaitkevi ius

planations of specific place names marking the sacred groves. Next to Alka, ventas (Holy) and Gojus groves, one could mention Perknas (God of Thunder), Laum (Fairy), Dievas (God) and Velnias (Devil) groves. Sometimes these sites mentioned in folk narratives coincide with historically documented groves but more often they do not. In any case, from the aspect of folklore, the panorama of sacred groves is significantly wider. Pieces of folklore, such as mythological tales and place legends, allude to the mythological aspects of sacred groves, which have never been recorded by historians. First, numerous mythological tales clearly suggest that the woods in general and sacred groves in particular have been viewed as strange and usually unfamiliar space, which was full of mythical power manifest in various forms in the natural world: plants, animals, etc. In the mythological sense these manifestations were closely related to the gods and deities: for example, hares were regarded as the hounds of goddess Medeina (equivalent of Greek Artemis and Roman Diana) and juniper was connected with the concept of life and rebirth and at the same time with some celestial gods: Perknas (god of thunder) and Saul (the Sun). Obviously, folklore materials could shed light on some important features of mythology in the general pattern of the prehistoric worldview. Second, according to folk narratives, pathway to the other worlds often leads through the woods sacred groves. Those who travelled to these worlds often encountered gods or the dead on their journey. In oral tradition about sacred groves in Lithuania, recorded in the late 19th and the 20th century, both above possibilities can be recognized: Velnias (Devil) can be visited in his home (see the popular tale type The Musician at the Devils Feast), while white beings in the shape of humans can be encountered or burning money (gold) observed. These are classical images of souls in the Baltic mythology (cf. Vaitkeviien 2001: 57ff). The same concept of souls being trapped in trees as in purgatory (according to Christian terminology) is reflected in legends referring to groves and separate trees as places of execution or accidents. This led to either avoidance of or respect towards these places among the people. Mentions of any ritual ceremonies (either pre-Christian or Christian) having been performed in the sacred groves are exceptionally rare. Moreover we cannot rule out the possibility that such motifs like People used to gather to the grove for celebrations in very ancient times or Pagan sanctuary was in use in the grove. Holy fire was supervised by competent girls (vaidilut s servants of the pagan priest) were created or re-created during the 19th and early 20th century. Despite the late chronology of folklore materials (the 19th20th century), they verify the existence of sacred groves in the areas inhabited by the Baltic tribes in the distant and the more recent past. Quite often the subject of oral

86

www.folklore.ee/folklore

The Sacred Groves of the Balts: Lost History and Modern Research

tradition still exists, and illustrates, in the form of human cultic activities (or results of these activities) the different manifestations of mythological and religious ideas. SACRED GROVES IN THE MODERN WORLD Traditions connected with sacred groves and especially individual sacred trees were alive in the 19th20th century, and still are in the early 21st century. However, compared to the pre-Christian period, the sacredness of groves and trees seems to be somehow dispersed. Sometimes the sacredness is present in small woodland areas in the form of a local natural holy place, sometimes it has been associated with nearby churches or rural cemeteries. It is occasionally located in villages and farmsteads or in their immediate surroundings. The local holy places in groves and forests are located mostly in Samogitia, the ethnographical region in western Lithuania with a predominantly Catholic population. Typically there is a group of trees of the same or different kind: pines, firs, birches, etc. Often one of them is older than others. Between the trees, there are one or several miniature wooden chapels with figurines of St Mary, Jesus Christ, or Saints as well as just crosses. The latter used to be monumental (those erected on the ground) or small pieces nailed to the tree trunk. Such an ensemble is traditionally surrounded by a stone wall or a simple fence (Fig. 2). Sometimes the ensemble also incorporates a natural or artificial well inside or, more often, outside the boundaries. Collective religious

Figure 2. The natural holy place located in the forest near Kirai (Teliai District). Photo by Saulius Lov ikas (1995). Courtesy of the author.

Folklore 42

87

Vykintas Vaitkevi ius

Figure 3. Ap ad kapeliai (Vows cemetery) located near Kairikiai (Akmen District). Drawn by Jauga (1929). Courtesy of B. Kerys.

activities were practised here once a year, usually in summertime. In the recent past, an ancient method of banging a wooden board hung on a tree in the holy place was used to call people together for a common prayer. While talking about the relationship between trees and Christian objects in the holy place, it should be pointed out that the religious focus is usually on figurines placed inside the chapel. The surrounding trees serve as supporters of crosses, chaplets and other small objects, as the custom of taking vows and offering votives is extremely dominant in this region. Yet, legends about the origin of such local holy places incorporate trees into particular mythological events. For example, it is told that the figurine of Jesus Christ was found in the tree and a candle was burning beneath and that it was a sign for people to build a house of god (= chapel) in this holy place. In general terms, this type of sacred groves embodies both pagan and Christian religious ideas. A grove with a group of trees in its centre is still an acceptable environment for Christian and sometimes semi-Christian ritual practices. For further research, it is worth mentioning that some of the above described groves (groups of trees) function at the same time as cemeteries (Fig. 3). It seems that burials took place there irregularly (e.g., during wars) but it is impossible to determine which function emerged first. Now both religious aspects are, say, interdependent cults. For example, Hail Mary prayers may take place in the period typical of the commemoration of the dead (in autumn), or one may set up a cross in commemoration of missing men in such a holy place. Separate trees like oaks, limes, firs, and especially pines are regarded as sacred, too. Sometimes the sacredness of a tree clearly depends on its location as demonstrated by examples of trees growing near churches or on the territory of rural cemeteries. Nobody was allowed to cut down such trees, except for Catholic priests fighting against elements of paganism in their parish (Fig. 4). Furthermore, sacred trees are often located simply at the roadside or the crossroads (Fig. 5). Sometimes they are just objects that people pass by on their way to natural holy place and/or cemetery. This aspect very likely affects

88

www.folklore.ee/folklore

The Sacred Groves of the Balts: Lost History and Modern Research

Figure 4. The so-called Fridays site near Digriai (Kaunas District). Built in 1837 near the sacred ash chapel of Jesus Heart, it was widely known as a place where Mass was held every Friday, as well as a pilgrimage destination. There was a double-stem ash grown into one at the back of the building until the priest ordered it to be cut down (soon after the chapel was consecrated). Photo by Vykintas Vaitkevi ius (1990).

Figure 5 . The sacred oak near U ukalnis (Prienai District), which is famous for its six holes shaped by multiple trunks and branches grown together. A special healing ritual which involved going naked through one of the holes at sunrise was carried out at the tree. Photo by Vykintas Vaitkevi ius (2008).

Folklore 42

89

Vykintas Vaitkevi ius

human behaviour and inspires people to perform certain ritual activities: offering a small votive (e.g., coins), carving a cross-sign on the tree trunk, erecting a small cross of two bound branches, or just praying there. Thus, in this context, sacred trees definitely appear as sacral objects and significant landmarks. Sacred or (based on somebodys hunch) inviolable trees like oaks, limes, ashes, maples, and others, are often located also on the territory of farmsteads. These trees are usually associated with ancestors who have lived on the farm and have planted a particular tree. The custom of planting a tree on the occasion of childbirth in the family was widely practised. The tradition spread sporadically even as late as in the middle of the 20th century. The trees growing near or in the yards of residential houses in rural areas are much older. Because of their old age and the preserved memory of ancestors, they were sometimes decorated with small wooden chapels or crosses. No significant ritual activities surrounding the sacred trees of this type are known but everyone who intended to cut down the tree in the farmstead must have paid respect to former generations (by paying for the Mass or giving alms to the beggars) (Vlius 1975: 238ff). In sum, there are many doubts as to whether it is possible to reconstruct ancient mythology and rites connected with groves that have disappeared in the landscape at some point in the past. But the tradition of sacred groves, smaller groups of trees, and separate trees, which, according to historical sources, can be traced back to pre-Christian times, is still enduring in the modern society. It seems reasonable to assume that the key idea of the grove has not significantly changed over the centuries. The part of the natural world that was unfamiliar to people was perceived as if another world on earth, as it was believed to hold supernatural powers represented by gods and the dead. And finally, even today a grove is chosen as a place for praying.

LOST HISTORY AND MODERN RESEARCH Modern research into the natural holy places often entails also sacred groves. A number of these were registered during the regional registration of sacred groves (see Vaitkeviius 1998, 2006). Place names, particularly Gojus grove, are most commonly used as evidence of the existence of sacred groves. Next to the place names, in-depth investigations have enabled scholars to discover major complexes of data consisting of linguistic, historical as well as folkloric evidences. The obtained information has been analysed relative to the actual landscape.

90

www.folklore.ee/folklore

The Sacred Groves of the Balts: Lost History and Modern Research

A selection of sacred groves which have been discovered in recent years can be presented: (1) Gojus grove located nearby Kernav (irvintos District, East Lithuania) should be considered an element of a famous archaeological complex of five hillforts, some burial grounds and barrow groups, unfortified settlements, etc. As the last stage of this complex is dated back to the 13th to late 14th century, the sacred grove very likely belongs to the same period. In the second half of the 13th century, Kernav was the residence of Traidenis, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (12691282). His estate was located on top of the hillfort called Aukuro kalnas. Nearby the Gojus grove there is a site called Kriveikikis (krivis chief (pagan) priest, kriv assemblage). Oral tradition is of considerable importance in this location. It was purposefully recorded only at the beginning of the 21st century and has revealed some unique aspects of the phenomenon of sacred grove (see Piasecka et al. 2005: 246ff). For example, in several accounts the conversion of the people of Kernav to Christianity has been described. According to legends it took place precisely in the above-mentioned grove beneath a sacred oak. One particular phrase based on this legend and Lithuanian history in general was known even in the 20th century namely, Polish Catholics recurrently told Lithuanian Catholics that the latter should go to the oak in the Gojus grove and renew their knowledge of Christianity (prayers, making cross-signs, etc.). Whether it is true or not, but one particular stump is still believed to be that of the onetime sacred oak. (2) Another Gojus grove worth mentioning is located near the city of Elektrnai, Central Lithuania (founded on the grounds of the former Perknakiemis village its name was derived from the words Perk nas god of thunder and kiemas village). There was a stump of a sacred oak known some time ago as well. Historically, Perknakiemis was a settlement of noblemen and was established in the 17th century, while the barrow group located in the Gojus grove in East Lithuania indicates that the sacredness of the natural holy place may have its roots in the pre-Christian period, as late as the 11th12th century (judging by a random find of a burnt wide-bladed axe). Perknas (the god of thunder) is the most striking character in the local narrative tradition even today. According to old legends he miraculously downed a Swedish army in this locality. He later also administered justice. Remarkably, one particular legend connects the genealogy of the Laimutis family with a sanctuary in the Gojus grove. The surname Laimutis stands for someone who is lucky in the direct sense of the word, while laim represents the concept of fortune itself and Laima is the goddess of fortune. Diminutive suffix -utis

Folklore 42

91

Vykintas Vaitkevi ius

expresses kinship relations between father (Laimis) and son (Laimutis). The family name Laimutis is spread in a relatively narrow area (Vanagas 1989: 16 17) and was never replaced by the Slavic equivalent S esna or esna. (3) The former site of the sacred grove called ventos Liepos (Sacred Lindens, originally recorded in Polish as Swiato Liepe, Les Swiatolipie) is located near the city of Trakai (Naujieji Trakai) the favourite residence of the Grand Duke of Lithuania in the late 14thearly 16th century. The grove still existed in the 16th18th century but had belonged to the nobles of Tottori origin since the late 15th century. A recent detailed investigation revealed that the Sacred Lindens grove located on a peninsula in Lake Galv constituted an element of a complex natural holy place covering the entire northern part of the lake including its islands, basin and the hilly lakeshore. According to folk etymology, the name Galv is connected with the word galva head and for that reason it is believed that the lake requests human sacrifice twice a year: just before freezing and at the time the ice melts. Surprisingly, in 1923 a fisherman accidentally found two unique artefacts there: human heads (measuring 7x11 cm and 6.5x8.9 cm), carved in sandstone, which today are held in the Trakai History Museum. (4) The former site of the sacred grove called Kukaveitis (the name has been derived from Kukas denoting one of the mythological beings and veita place) is located near Maiiagala (Vilnius District). According to Historia Polonica written by Jan Dugosz in the 15th century, the Grand Duke Algirdas was ceremonially burned in 1377 in the Kukaveitis (originally Latin Kokiveithus)3 grove (Vlius 1996: 556). No traces of it having been a cultic place have been identified so far, but the natural boundaries (slopes of the hill) and the geographical description of the area date back to the 18th century. At the time, the former territory of the Kukaveitis grove was occupied by some scattered farmsteads, already called by the same name, Kukaveitis. Recently, two East-Lithuanian barrow groups were discovered to the north and east of the Kukaveitis grove site, and some destroyed cremation burials dated to the 10th11th century were discovered. A bronze ring-shaped brooch from the late 14th century was accidentally found there as well. All the discussed examples, in particular those described under points (1), (3), and (4), are highly compatible with the historical evidence of the 16th century concerning the Lukiks sacred grove in Vilnius, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania during its pagan period. The presence of sacred groves in the very surroundings of Kernav (the first known residence of the Grand Duke), Trakai (the second), and Vilnius (the third), indicate the importance of groves in the pre-Christian religion of the period of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (c. 1183/12361387). However, there is still no precise answer as to whether

92

www.folklore.ee/folklore

The Sacred Groves of the Balts: Lost History and Modern Research

these groves were connected with the religion in a passive way (perhaps just in mythological perceptions) or were used as a space for active ritual practices (e.g., hunting and sacrificing on special occasions, cremation or burying of the dead). Later periods in the history of sacred groves are much more accurately represented, although it is generally acknowledged as the time of decline. Besides, Christianity became a factor that has significantly influenced the former nature of the tradition. The large amount of data concerning the sacred groves that has been discussed in this article illustrates the remarkable linguistic background (the alka concept), the historical context (natural holy places usually accommodate some other sacral objects) and numerous references to sacred groves in folklore. Archaeological evidences are rather scarce but the subject could be expanded in the course of research into particular features of cultural landscape in the near future. Finally, it should be underlined that a non-complex approach to the sacred groves (which is still practiced by linguists, historians and folklorists) cannot benefit the research. Methods used by natural sciences would offer different stimulating possibilities for investigating sacred groves and former grove sites, even though it has never been tested in Lithuania so far.

NOTES

1

The number of copies of this publication, which was published at the Baltic University in Tbingen, Germany just after the Second World War, was unfortunately extremely limited. It is even believed that this concept, which is rooted in the worldview of the Baltic tribes, should be regarded as the very first historical stage of the development of the protected areas in modern Lithuania (Bakyt et al. 2006: 78). Other variations of this place name in the 16th- to 18th-century documents are: KaKoweytis, Kukaweytis, Kukowajtys, etc.

REFERENCES

Balikonis, Juozas (ed.) 1941. Lietuvi kalbos odynas. [Dictionary of the Lithuanian Language.] Vol. 1. Kaunas: Institute of the Lithuanian Language. Balys, Jonas 1966. Lietuvi liaudies pasaul jauta tik jim ir papro i viesoje. [World Conception in Lithuanian Folklore.] Chicago: Draugas. Bakyt, Rta; Bezaras, Vidmantas; Kavaliauskas, Paulius; Klimaviius, Algimantas & Raius, Gediminas (eds.) 2006. Lietuvos saugomos teritorijos. [Protected Areas in Lithuania.] Kaunas: Lutut.

Folklore 42

93

Vykintas Vaitkevi ius

Dundulien, Pran 1979. Med iai senov s lietuvi tik jimuose. [Trees in the Beliefs of Ancient Lithuanians.] Vilnius: Mintis. Ivinskis, Zenonas 1938/1986. Medi kultas lietuvi religijoje. [Cultus arborum in antiqua religione lituanorum.] In: P. Jatulis (ed.) Rinktiniai ratai. Roma: Lietuvi Katalik Mokslo Akademija, Vol. 2, pp. 348407. [Offprint from Soter, Vol. 15, pp. 140176 and Soter, Vol. 16, pp. 113144.] Karulis, Konstantns 1992. Latvieu etimoloijas v rdn ca. [Latvian Etymologial Dictionary.] Vol. 1/2. Rga: Avots. Lukait, Ing (ed.) 2006. Matthaeus Praetorius. Deliciae Prussicae, oder Preussische Schaubhne. Vol. 3. Vilnius: LII leidykla. Martinkus, Ada 1989. Egl, la reine des serpens. Paris: Institut dthnologie. Piasecka, Beata; Stankeviit, Ida & Vaitkeviius, Vykintas 2005. Vilniaus apylinki padavimai. [The Local Legends of the Vilnius Region.] Tautosakos darbai. Vol. 22 (29), pp. 219261. turms, Eduards 1946. Die Alksttten in Litauen. Contributions of Baltic University. Vol. 3, pp. 135. turms, Eduards 1948. Baltu tautu svtmei. [The Baltic Holy Groves.] Sauksme. Vol. 1/2, pp. 1721. Urtns, Juris 1989. Sviashchennye lesa i roshchi v Latvii. [Holy Forests and Groves in Latvia.] In: Arkheologiia i istoriia Pskova i Pskovskoi zemli 1988. Tezisy dokladov nauchno-prakticheskoi konferentsii. Pskov, pp. 6163. Vaitkeviien, Daiva 2001. Ugnies metaforos. Lietuvi ir latvi mitologijos studija. [Metaphors of Fire: A Study of Lithuanian and Latvian Mythology.] Vilnius: Lietuvi literatros ir tautosakos institutas. Vaitkeviius, Vykintas 1998. Senosios Lietuvos ventviet s. emaitija. [The Sacred Sites of Lithuania. Samogitia.] Vilnius: Diemedio leidykla. Vaitkeviius, Vykintas 2004. Studies into the Balts Sacred Places. BAR International Series, 1228. Oxford: John and Erica Hedges, Ltd. Vaitkeviius, Vykintas 2006. Senosios Lietuvos ventviet s. Auktaitija. [Ancient Sacred Places of Lithuania. Auktaitija (Upland) Region.] Vilnius: Diemedio leidykla. Vanagas, Aleksandras (ed.) 1989. Lietuvi pavard i odynas. [Dictionary of Lithuanian Family Names.] Vol. 2. Vilnius: Mokslas. Vlius, Norbertas (ed.) 1975. iaur s Lietuvos sakm s ir anekdotai. Surinko M. Slan iauskas. [North-Lithuanian Narratives and Jokes. Collected by M. Slaniauskas.] Vilnius: Vaga. Vlius, Norbertas (ed.) 1996. Balt religijos ir mitologijos altiniai. [Sources of Baltic Religion and Mythology.] Vol. 1. Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedij leidykla. Vlius, Norbertas (ed.) 2001. Balt religijos ir mitologijos altiniai [Sources of Baltic Religion and Mythology.] Vol. 2. Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedij leidykla. Wenskus, Reinhard 1968. Beobachtungen eines Historikers zum Verhltnis von Burgwall, Heiligtum und Siedlung im Gebiet der Preussen. In: M. Claus, W. Haarnagel & K. Raddatz (eds.) Studien zur europischen Vor- und Frhgeschichte. Neumnster: Wachholtz, pp. 311328.

94

www.folklore.ee/folklore

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Gary B. Ferngren-Medicine and Health Care in Early Christianity (2009) PDFDocument261 paginiGary B. Ferngren-Medicine and Health Care in Early Christianity (2009) PDFMaría Florencia Saracino100% (3)

- Archaeologia BALTICA 9Document112 paginiArchaeologia BALTICA 9Ewa Draugia SiemaszkoÎncă nu există evaluări

- M O N T A N A Praesidium Regio Municipiu PDFDocument82 paginiM O N T A N A Praesidium Regio Municipiu PDFComfort DesignÎncă nu există evaluări

- Markus - Saeculum - History and Society in The Theology of ST Augustine PDFDocument280 paginiMarkus - Saeculum - History and Society in The Theology of ST Augustine PDFmahomax1Încă nu există evaluări

- Abraczinskas Ancestry1Document87 paginiAbraczinskas Ancestry1James Dwyer100% (2)

- The noble Polish family Ines. Die adlige polnische Familie Ines.De la EverandThe noble Polish family Ines. Die adlige polnische Familie Ines.Încă nu există evaluări

- The Provenance of Pre-Contact Copper Artifacts: Social Complexity and Trade in The Delaware ValleyDocument13 paginiThe Provenance of Pre-Contact Copper Artifacts: Social Complexity and Trade in The Delaware ValleyGregory LattanziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian History of NYS - Part 1. William Ritchie. Educational Leaflet No 6.Document44 paginiIndian History of NYS - Part 1. William Ritchie. Educational Leaflet No 6.Antony TÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hulchanski Family: The First Two Generations in North AmericaDocument74 paginiHulchanski Family: The First Two Generations in North Americawdhul100% (2)

- Śladami Łemków" by Roman Reinfuss. English Language Summary of The Book.Document8 paginiŚladami Łemków" by Roman Reinfuss. English Language Summary of The Book.Corinna CaudillÎncă nu există evaluări

- Russian Naming ConventionsDocument19 paginiRussian Naming Conventionsryanash777100% (1)

- ShogiDocument5 paginiShogiannca7Încă nu există evaluări

- Doyle White - S - The Meaning of - Wicca - A Study in Etymology, History and Pagan Politics - 2Document23 paginiDoyle White - S - The Meaning of - Wicca - A Study in Etymology, History and Pagan Politics - 2V.F.Încă nu există evaluări

- Christopher Scott Thompson - Pagan AnarchismDocument127 paginiChristopher Scott Thompson - Pagan AnarchismCh Morencio80% (5)

- When Children Became People - The Birth of Childhood in Early Christianity (Review) PDFDocument6 paginiWhen Children Became People - The Birth of Childhood in Early Christianity (Review) PDFcatherine_m_rose6590Încă nu există evaluări

- Archaeologia BALTICA 11Document361 paginiArchaeologia BALTICA 11Nata Kha100% (2)

- Lituânia. Lithuanian CultureDocument6 paginiLituânia. Lithuanian CultureviagensinterditasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ruthenians RUSINIDocument5 paginiRuthenians RUSINIandrejnigelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Index Slavic Res.Document42 paginiIndex Slavic Res.goranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eastern Europe Czech Republic v1 m56577569830516526Document33 paginiEastern Europe Czech Republic v1 m56577569830516526Raman GoyalÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mann Site & The Leake Site: Linking The Midwest and The Southeast During The Middle Woodland PeriodDocument27 paginiThe Mann Site & The Leake Site: Linking The Midwest and The Southeast During The Middle Woodland PeriodScot Keith100% (1)

- Lithuanian Pronunciation Guide - by Dick OakesDocument1 paginăLithuanian Pronunciation Guide - by Dick OakesPablo Di MarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kivimae LivoniaDocument12 paginiKivimae LivoniaDace BaumaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lithuanian GeneaologyDocument23 paginiLithuanian Geneaologypetgisdav673367% (3)

- Ancient Macedonian Studies in Honor of Charles F. EdsonDocument408 paginiAncient Macedonian Studies in Honor of Charles F. Edsonkakashi 2501Încă nu există evaluări

- Viking Identities and Ethnic Boundaries in England and Normandy PDFDocument332 paginiViking Identities and Ethnic Boundaries in England and Normandy PDFIonut AtudoreiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Polish-Ukrainian WarDocument16 paginiPolish-Ukrainian WarPaul CerneaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hebrew Gravestone InterpretationDocument21 paginiHebrew Gravestone Interpretationkakachulo100% (1)

- Kirakos Gandzaketsi's History of The ArmeniansDocument114 paginiKirakos Gandzaketsi's History of The ArmeniansRobert G. BedrosianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Memory Book: The Village of HanczowaDocument50 paginiMemory Book: The Village of HanczowaTheLemkoProjectÎncă nu există evaluări

- Limes EnglishDocument33 paginiLimes EnglishRendax2000100% (1)

- Language Museums of The WorldDocument138 paginiLanguage Museums of The WorldmishimayukioÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2019 Svaneti TextsDocument12 pagini2019 Svaneti TextsSydney Nicoletta W. FreedmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Golden Horde and Its Urban Development On The Lower Volga Basin-Two Saray Cities in 13th Century-Leventelpen - AcademiaDocument7 paginiThe Golden Horde and Its Urban Development On The Lower Volga Basin-Two Saray Cities in 13th Century-Leventelpen - AcademiaLevent ElpenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coast Salish HistoryDocument2 paginiCoast Salish HistoryJustin SetoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ukraine Україна: Fast FactsDocument25 paginiUkraine Україна: Fast FactsRaman GoyalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kuman Belt From TomasevacDocument5 paginiKuman Belt From TomasevaczimkeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Rosetta StoneDocument24 paginiThe Rosetta StoneRenatoConstÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Search of American Place-Name Origins: Clues to Understanding Our Nation's Past and PresentDe la EverandIn Search of American Place-Name Origins: Clues to Understanding Our Nation's Past and PresentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mining BibliographyDocument27 paginiMining BibliographyVladan StojiljkovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eastern-Europe-Hungary v1 m56577569830516530Document32 paginiEastern-Europe-Hungary v1 m56577569830516530Josep G. CollÎncă nu există evaluări

- Karl Kaser - The Balkan Joint Family - Redefining A ProblemDocument27 paginiKarl Kaser - The Balkan Joint Family - Redefining A Problemakunjin100% (1)

- Livonian CrusadeDocument8 paginiLivonian CrusadeDuncÎncă nu există evaluări

- Souvenirs of Venice Reproduced Views Tourism and City Spaces PDFDocument333 paginiSouvenirs of Venice Reproduced Views Tourism and City Spaces PDFAlejo GabrielÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Caucasus Front During WwiDocument18 paginiThe Caucasus Front During WwijuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tyranny and ColonizationDocument20 paginiTyranny and ColonizationMarius JurcaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inventing Balkan Identities Finding TheDocument29 paginiInventing Balkan Identities Finding TheHistorica VariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pope John VIIIDocument3 paginiPope John VIIIFigigoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The North-Eastern Frontiers of Medieval EuropeDocument439 paginiThe North-Eastern Frontiers of Medieval Europealecio75Încă nu există evaluări

- Lba in Dalmatia BarbaricDocument13 paginiLba in Dalmatia BarbaricVedran BarbarićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper, 2021Document14 paginiPaper, 2021ISSV Library Resources100% (1)

- Dividing the spoils: Perspectives on military collections and the British empireDe la EverandDividing the spoils: Perspectives on military collections and the British empireÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gürsoy-Naskali & Halén-1991-Cumucica & Nogaica (OCR)Document172 paginiGürsoy-Naskali & Halén-1991-Cumucica & Nogaica (OCR)Uwe BlaesingÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Archaeological History of The Wendat: An OverviewDocument65 paginiThe Archaeological History of The Wendat: An OverviewT.O. Nature & DevelopmentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Genealogy in The Vienna War ArchivesDocument20 paginiGenealogy in The Vienna War ArchivesChirita Cristian100% (1)

- Sharp Turning-Point Armenian MythomaniaDocument24 paginiSharp Turning-Point Armenian MythomaniaErden SizgekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eastern-Europe-Romania v1 m56577569830516555Document38 paginiEastern-Europe-Romania v1 m56577569830516555Raman GoyalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assyrian Military Practices PDFDocument15 paginiAssyrian Military Practices PDFJuan Gabriel PiedraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Die Mosaiken WestkleinasiensDocument3 paginiDie Mosaiken WestkleinasiensHULIOSMELLAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roman ConsulDocument7 paginiRoman ConsulUsername374Încă nu există evaluări

- ALEKSHIN, V. 1983 - Burial Customs As An Archaeological SourceDocument14 paginiALEKSHIN, V. 1983 - Burial Customs As An Archaeological SourceJesus Pie100% (1)

- A Region of TreasuresDocument2 paginiA Region of TreasuresGeorgian National MuseumÎncă nu există evaluări

- MKL - DD-Paco - The Ottoman Empire in Early Modern Austrian History PDFDocument17 paginiMKL - DD-Paco - The Ottoman Empire in Early Modern Austrian History PDFyesevihanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Black Etruscan PigmentDocument7 paginiBlack Etruscan PigmentanavilelamunirÎncă nu există evaluări

- CushiticNumerals FoliaOrientalia 55 2018 1Document28 paginiCushiticNumerals FoliaOrientalia 55 2018 1alebachew biadgieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Genetic Heritage of Croatians in The Southeastern European Gene Pool-Y Chromosome Analysis of The Croatian Continental and Island PopulationDocument9 paginiGenetic Heritage of Croatians in The Southeastern European Gene Pool-Y Chromosome Analysis of The Croatian Continental and Island PopulationJan KowalskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Steve HurleyDocument1 paginăSteve Hurleyannca7Încă nu există evaluări

- Oana Lavinia Ciuca Etapele Ideologizarii Conceptului de Emancipare A FemeiiDocument18 paginiOana Lavinia Ciuca Etapele Ideologizarii Conceptului de Emancipare A FemeiiIlie MarinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Steve Hurley2Document1 paginăSteve Hurley2annca7Încă nu există evaluări

- RadioDocument1 paginăRadioannca7Încă nu există evaluări

- CDSP Paper HoogheDocument41 paginiCDSP Paper Hoogheannca7Încă nu există evaluări

- Attp 3-39.32Document162 paginiAttp 3-39.32"Rufus"Încă nu există evaluări

- Dichloroacetic Aci3Document10 paginiDichloroacetic Aci3annca7Încă nu există evaluări

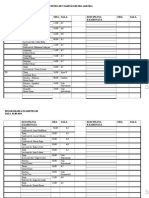

- 1534 - Programarea Examenelor Sem I Fac de Drept Si Stinte SocialeDocument15 pagini1534 - Programarea Examenelor Sem I Fac de Drept Si Stinte Socialeannca7Încă nu există evaluări

- 2014 Beijing Technology and Business University Master ProgramsDocument2 pagini2014 Beijing Technology and Business University Master Programsannca7Încă nu există evaluări

- Dichloroacetic AcidDocument10 paginiDichloroacetic Acidannca7Încă nu există evaluări

- Dichloroacetic Aci3Document10 paginiDichloroacetic Aci3annca7Încă nu există evaluări

- Filocalia Vol.7Document528 paginiFilocalia Vol.7Catalin VoinescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dichloroacetic Aci3Document10 paginiDichloroacetic Aci3annca7Încă nu există evaluări

- Dichloroacetic AcidDocument10 paginiDichloroacetic Acidannca7Încă nu există evaluări

- Learn Assyrian Online: 3ynat1kabas 0anaml 3ylo0 3ylo0Document42 paginiLearn Assyrian Online: 3ynat1kabas 0anaml 3ylo0 3ylo0MarcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Awe-Inspiring Pictures of Shaolin Monks Training: On August 2, 2014 by Physical CulturistDocument30 paginiAwe-Inspiring Pictures of Shaolin Monks Training: On August 2, 2014 by Physical Culturistannca7Încă nu există evaluări

- The Role of The Ottomans and Dutch in The Commercial Integration Between The Levant-Mehmet BulutDocument35 paginiThe Role of The Ottomans and Dutch in The Commercial Integration Between The Levant-Mehmet Bulutannca7Încă nu există evaluări

- Dance in Prehistoric Europe - Yosef GarfinkelDocument10 paginiDance in Prehistoric Europe - Yosef GarfinkelvicostoriusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aramaic MateiDocument0 paginiAramaic Mateiannca7Încă nu există evaluări

- 04 ILiA Lesson03Document6 pagini04 ILiA Lesson03Iarmis SaimirÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of World Societies Combined Volume 10th Edition Mckay Test BankDocument12 paginiHistory of World Societies Combined Volume 10th Edition Mckay Test Bankpucelleheliozoa40wo100% (27)

- Julians Pagan RevivalDocument27 paginiJulians Pagan RevivaljacintorafaelbacasÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Cor 8.7-13 - Danger of IdolatryDocument18 pagini1 Cor 8.7-13 - Danger of Idolatry31songofjoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Myatt and PaganismDocument44 paginiMyatt and PaganismSteve BesseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Religion: Lesson 3 "The Locus For Dialogue With God" The Old Testament Has No Specific Word For Conscience. Instead, It Employs TheDocument6 paginiReligion: Lesson 3 "The Locus For Dialogue With God" The Old Testament Has No Specific Word For Conscience. Instead, It Employs TheMitzi YoriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mothers, Maids and The Creatures of The NightDocument19 paginiMothers, Maids and The Creatures of The NightLKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Religious Conflict in Late Antique AlexaDocument18 paginiReligious Conflict in Late Antique Alexastratulatmaria05_192Încă nu există evaluări

- Cemetery Symbols in StoneDocument6 paginiCemetery Symbols in StoneWrite100% (1)

- What Do We Actually Know About MohammedDocument6 paginiWhat Do We Actually Know About MohammedCalvin OhseyÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is WitchcraftDocument4 paginiWhat Is WitchcraftRemenyi ClaudiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heresy - 1d4chanDocument15 paginiHeresy - 1d4channunya biznessÎncă nu există evaluări

- Celtic Wicca - WikipediaDocument2 paginiCeltic Wicca - WikipediaNyx Bella DarkÎncă nu există evaluări

- GPCR ADb J4 JuDocument200 paginiGPCR ADb J4 JuNenad Marković67% (3)

- Teutonic Mythology v1 1000028853 PDFDocument507 paginiTeutonic Mythology v1 1000028853 PDFEsteban SevillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biblical AllusionsDocument2 paginiBiblical AllusionsalexÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cyril of Alexandria and Julian The EmperDocument15 paginiCyril of Alexandria and Julian The EmperHugoFernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Christmas: The Biggest Pagan HolidayDocument27 paginiChristmas: The Biggest Pagan HolidayleahkjfriendÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Place of The Earth-Goddess Cult in English Pagan ReligionDocument352 paginiThe Place of The Earth-Goddess Cult in English Pagan ReligionFree_AgentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ignou Socio Unit 4Document14 paginiIgnou Socio Unit 4sucheta chaudharyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is The Quran The Word of SatanDocument38 paginiIs The Quran The Word of SatanAbdullah Yusuf0% (1)

- Page DuBois - A Million and One Gods (2014) (A)Document208 paginiPage DuBois - A Million and One Gods (2014) (A)Lu Bacigalupi100% (2)

- (BUTLER) Facts For The Times PDFDocument286 pagini(BUTLER) Facts For The Times PDFNicolas MarieÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Christian and TattoosDocument6 paginiThe Christian and TattoosCurtis PughÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practical Idealism - English Translation PDFDocument61 paginiPractical Idealism - English Translation PDFBookAncestorÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Lost Tribes and The Saxons of The East and of The West, With New Views of Buddhism, and Translations of Rock-Records in India Part 1Document242 paginiThe Lost Tribes and The Saxons of The East and of The West, With New Views of Buddhism, and Translations of Rock-Records in India Part 1Daniel Álvarez Malo100% (1)