Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Teaching Philosophy

Încărcat de

Shelby NicoleDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Teaching Philosophy

Încărcat de

Shelby NicoleDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

I Believe in Music Education A Teaching Philosophy Shelby Thompson

In order to become an effective teacher, one must clearly develop a philosophy on which to base their teaching. A philosophy is not meant just to be a cognitive proposal, but rather a written personal reflection of what one believes should be incorporated into their teaching. It is in the philosophy where we, as teachers, find direction in leading students toward the goal of achieving the skill of understanding. In music education, we will strive to create Musical Understanding, an ability to continue to foster outside of the classroom that will continue for the remainder of their lives. Georgina Barton and Kay Hartwig explain that it is important for pre-service music teachers [] to develop a personal philosophy to music education before entering the teaching profession as it impacts on many aspects [] such as planning and assessment (Barton & Hartwig, 2012, p. 3). When students successfully score on standardized tests, which require recitation of learned facts, some would think them knowledgeable. However, while those learned facts may be important, the ability to comprehend those facts within a greater context is equally, if not more important. When students have the ability to make connections from within a discipline to outside that disciplines context, it is evidence that the student has successfully acquired the skill of understanding. To be able to aid students in acquiring this skill directs teaching through the formation, as well as implementation of a personal philosophy.

In our information-age world, the idea that music is a vital part in everyday life is puzzling to some people. There are numerous people who assume that the arts are luxuries instead of necessities, and that words and pictures are the only ways to influence the human mind. People who do not appreciate music assume that music has no greater significance other than providing temporary pleasure. Some people also consider music to be gloss upon the surface of life or a harmless indulgence rather than a necessity (Storr). It is perhaps for this

reason why politicians of the present day hardly ever place music in a major place for their educational plans. Today, when education is becoming predominantly directed towards obtaining profitable employment rather than toward enriching personal experience, music is likely to be, however wrongfully, seen as an extra in the school curriculum and as a subject that does not need to be provided for students who are obviously not musical by nature since the significance of music, in recent years, has been highly underestimated.

Richard Gill, a powerhouse for Australian music education advocacy, was asked to reflect on his fiftieth anniversary as a music teacher to which he provided the statement; We learn music because it is good. We learn music because it is unique. We learn music because it stimulates creativity at a very high level. No other reasons for teaching music are needed. Alongside Gill, music educators of the last eighty-years, such as David Elliott and Zoltan Kodaly, have held similar ideals about music education. Kodaly believed that music education is like rich vitamins, which are essential for children that should begin at a young age (KMEIA, 2013). Elliott discusses the idea of music education in a holistic manner. In addition to this Elliott addresses various concepts of a music education philosophy and then places the ideas on one concept of musicianship and educatorship (Elliott, 1995, p. 262). Elliott discusses the idea that to teach music effectively, a teacher must possess, embody, and exemplify musicianship (Elliott, 1995, p. 262). He continues to discuss various ideas of excellent teaching and musically proficient and expert teachers (Elliott, 1995, p. 262). It is beneficial to students to be given the opportunity to participate in and experience a variety of music at all levels of education from elementary through to post-secondary. There is discrepancy on how to go about providing that musical experience. There are a few major

philosophical foundations that are at odds with each other; believe that it is far more important to find a synergistic way to combine these feuding ideologies. The most logical way is through absolute expressionism. Absolute expressionism is an attempt to take the best of all ideologies and combine them in such a way that as a music educator, I will educate my students in musicality and interpretations of music that are consistently based in the cognitive understandings of composition, form, theory, history, and pedagogy. Through this style of music education, the student can utilize the absolute expressionist in them and a true musical experience that will have impact in their life will be created. At no point in the Alberta music curriculum does it state what method of teaching should be used in delivering this content. Allowing this freedom for teachers means that the content stays the same but the delivery can be differed depending on the school context that the teacher is present in.

Methodologies in regards to their practice, implementation and theory, appear in my experience to be major discussion point in the conversation regarding music education. Gills thoughts of there being not one perfect method to teach music can at times appear to be true. He continues to state that no single solution suits every circumstance (Gill, 2012). This view of music education is a rather black and white way of looking at the situation. There are many examples of schools where very fundamental implementation works perfectly for the school culture. In parallel to this, practicing teacher Dr. James Cuskelly defines the successful use of a method when it is most successfully organized and delivered when it is primarily conceived in terms of engaged music making (Cuskelly, 2006, p. 57). Taking both of these opinions into consideration, some of the various opinions for music education methods include: Orff Schulwerk, Dalcroze Eurhythmics, Suzuki and Kodaly. Apart from these methods, various

classroom teachers teach using theory based ideas rather than a sequentially arranged aural and movement based methods.

Orff Schulwerk concerns itself with the needs and musical teaching of each child through activities of music and movement (AOSA, 2013). Similarly to Orff Schulwerk, Dalcroze Eurhythmics has a strong emphasis on music and movement (ANCOS, 2011). The Dalcroze method is based on the premise that the human body is the source of all musical ideas (Dalcroze QLD, 2013). This meaning is then applied in music making when the idea of musicianship and artistry is in the whole person, not just the fingers and the brain (Dalcroze QLD, 2013). This idea is resonated in the Suzuki approach in regards to the approach of the whole child, however the Suzuki method is by far vastly different to both Orff and Dalcrozes approaches. Suzuki based his method around the idea that children learn their native tongue with relative ease and is encouraged by their mothers love as well as the positive family environment (Suzuki, 1969, p. 23). Suzukis aural based method postpones the use of reading music until the child is well established in their aural and instrumental abilities. Therefore the learning process requires listening, imitating and repeating. This approach to music education is at times both student and teacher centered however without a good teacher model, both musically and technically, this method appears to be redundant (Suzuki, 1969). The Kodaly method is founded in the ideals of giving back to the people of Hungary their own musical heritage (Choksy, 1990, p. 1) and improving the overall level of music literacy. The Kodaly method sees the sequencing of the content to be in line with a childs development (Choksy, 1990, p. 10). Which like the Suzuki method uses the native tongue as a starting point. However Kodaly places emphasis on literacy as well as aural based skills, therefore all dimensions of music are being made conscious continuously (Choksy, 1990). The Kodaly method utilizes

tools from various places including: Cheve French time names, Curwen hand signs and Arezzos movable-do system of solminzation (Choksy, 1990, p. 12). However the foundation of the method is this notion of singing, Kodaly believed that singing provides the best start to music education even the most talented artist can never overcome the disadvantages of an education without singing (Kodaly, 1974). The use of the voice in music education is the most accessible of all instruments and correct instruction can lead to a highly developed musical ear (KMEIA, 2013). These concepts inline with well-trained music teachers make this method achievable, however risky in a school environment.

With the choice of so many ways of teaching music, the question arises as to why does it matter which method we use. Certainly the thought of teaching music a different ways is irrelevant given the content remains the same. Therefore with this level of choice for the teacher it is most important that the choices made are appropriate to the curriculum as well as to the teachers themselves. On reflection there isnt much difference in the methods apart from a few pinnacle beliefs. My musicianship and my music background, although not heavily vocal based, leads towards those ideals of the Kodaly Method. I believe that it is fair to say that the curriculum I would like to teach lends itself to the Kodaly method. This is not just in the way that the elements of music are sequenced but also the incorporation of subject material and cross-curricular opportunities.

Allowing our students to have the best chance with their educational journey is most important in a school environment, however in music it is the confidence we can provide for them to achieve, will be most beneficial (Cuskelly, 2006), therefore we should begin musical training at a young age. Musical training affects the structure and function of different

regions of the brain, how those regions communicate during the creation of music, and how the brain processes different sensory stimuli. These insights point to potential new roles for musical training, including fostering brain plasticity, providing an alternative educational tool, and treating learning disabilities. Playing a musical instrument is a multisensory and motor experience that stimulates emotions and motions, and engages pleasure and reward systems in the brain. It has the potential to change brain function and structure when done over a long period of time. Researchers found that musical training at a young age may strengthen the brain, especially regions that influence language skills and executive function. They found that the volume of brain regions related to hearing and self-awareness appeared to be larger in those who began taking music lessons before age 7. This hints that early musical training could potentially be used as a therapeutic tool. "Early musical training does more good for kids than just making it easier for them to enjoy music; it changes their brain and these brain changes could lead to cognitive advances as well. Our study provides evidence that early music training could change the structure of the brain's cortex. (Brooks, 2013).

I believe that as a pre-service teacher it is important for my own learning to develop a personal philosophy to music education before I teach. As Barton and Hartwig state, having a philosophy to music education enables students to clearly articulate the meaning of music not only in their own lives but also their students (Barton & Hartwig, 2012, p. 3). As a teacher I wish to enable every child to understand and appreciate music, whether they do or do not pursue music. I also want to disregard this notion of music being only for the talented few. Of course there will always be those gifted students who excel in composition or performance. However there will be a place, for those who allow it, to be a part of this community of music making and general enjoyment. Indeed it should not be disregarded that students too will bring

their own knowledge to the classroom and they can be learnt from as well. I will strive for my own teaching practice to reflect these beliefs, and I too will not attempt to become accustom to old ways of teaching for being in the profession of teaching is being in the profession of life long learning.

Bibliography American Orff-Schulwerk Association (n.d.). What is Orff Schulwerk?. Retrieved February 2, 2014, from http://www.aosa.org/orff.html. Australian National Orff-Schulwerk Council (2011). About Orff Australian National Council of Orff Schulwerk (ANCOS). Retrieved April 8, 2013, from http://www.ancos.org.au/main/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=13&Itemid=4 Barton, G., Hartwig, K., & Griffith University (2012). Where is Music?: A philosophical approach inspired by Steve Dillon. Australian Society for Music Education Incorporated, 2(1), 3 9. Brooks , M. (2013, November 18). More evidence that music benefits the brain. Retrieved from http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/814540 Choksy, L. (1990). The Kodaly Method I: Comprehensive Music Education (3rd ed.). New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. Cuskelly, J. M. (2006). The search for meaning in music education: Reflections on difference and practice. University of Queensland. Dalcroze Australia (n.d.). Eurythmics1. Retrieved February 2, 2014, from http://www.dalcroze.org.au/eurythmics1.html KMEIA (2013). The Kodly Concept. Retrieved February 2, 2014, from http://www.kodaly.org.au/index.php/concept Limelight (2013, January 19). Every child needs music: Richard Gill still arguing 50 years on. Classical Music: Limelight Magazine. Retrieved February 2, 2014, from http://www.limelightmagazine.com.au/Article/329408,every-child-needs-music-richard-gillstill-arguing-50-years-on.aspx Reimer, Bennet. A philosophy of music education: Advancing the vision. Prentice-Hall. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. 2003. Storr, Anthony. Music and the mind. Ballentine. New York, New York. 1992. Suzuki, S. (1969). Nurtured by love (5th ed.). New York, USA: Exposition Press. Wasiak, E. B. (2013). A case for instrumental music in Canadian schools In Teaching Instrumental Music in Canadian Schools Don Mills, Ontario : Oxford University Press.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Progress Test Files 1-6 Answer Key A Grammar, Vocabulary, and PronunciationDocument8 paginiProgress Test Files 1-6 Answer Key A Grammar, Vocabulary, and PronunciationEva Barrales0% (1)

- Rizal's Travel TimelineDocument43 paginiRizal's Travel TimelineJV Mallari61% (80)

- Management of Curriculum and InstructionDocument29 paginiManagement of Curriculum and InstructionRose DumayacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motivation LTRDocument1 paginăMotivation LTREhtesham UddinÎncă nu există evaluări

- TR HEO (On Highway Dump Truck Rigid)Document74 paginiTR HEO (On Highway Dump Truck Rigid)Angee PotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Padagogy MathsDocument344 paginiPadagogy MathsRaju JagatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Michigan School Funding: Crisis and OpportunityDocument52 paginiMichigan School Funding: Crisis and OpportunityThe Education Trust MidwestÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edu 201 - Observation PacketDocument15 paginiEdu 201 - Observation Packetapi-511583757Încă nu există evaluări

- Final Score Card For MBA Jadcherla (Hyderabad) Program - 2021Document3 paginiFinal Score Card For MBA Jadcherla (Hyderabad) Program - 2021Jahnvi KanwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- EDTECH 1 Ep.9-10Document17 paginiEDTECH 1 Ep.9-10ChristianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supervision in NursingDocument24 paginiSupervision in NursingMakanjuola Osuolale John100% (1)

- Youth Participation Project-Full Report Acc2Document31 paginiYouth Participation Project-Full Report Acc2Danilyn AndresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bangalore City CollegeDocument3 paginiBangalore City CollegeRamakrishnan AlagarsamyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tutorial Letter FMM3701-2022-S2Document11 paginiTutorial Letter FMM3701-2022-S2leleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sow The SeedDocument3 paginiSow The SeedSunday OmachileÎncă nu există evaluări

- + Language Is Text-And Discourse-BasedDocument7 pagini+ Language Is Text-And Discourse-BasedtrandinhgiabaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resume CurrentDocument1 paginăResume Currentapi-489738965Încă nu există evaluări

- Nov2017 GeotechnicalEngineering JGB Part1Document121 paginiNov2017 GeotechnicalEngineering JGB Part1Kim Dionald EimanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preface of The Course File Lab-1 NewDocument7 paginiPreface of The Course File Lab-1 Newtheeppori_gctÎncă nu există evaluări

- CVDocument5 paginiCVapi-267533162Încă nu există evaluări

- Defense Panel Report Sheet CRCDocument2 paginiDefense Panel Report Sheet CRCMyca DelimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Second Semester 2022 - 2023 Academic Calendar - UTG-27Document3 paginiSecond Semester 2022 - 2023 Academic Calendar - UTG-27Liana PQÎncă nu există evaluări

- BLRB Stadium ProjectsDocument7 paginiBLRB Stadium Projectssabarinath archÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aparchit 1st August English Super Current Affairs MCQ With FactsDocument27 paginiAparchit 1st August English Super Current Affairs MCQ With FactsVeeranki DavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- EF4e Intplus Filetest 10bDocument7 paginiEF4e Intplus Filetest 10bLorena RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- LipsDocument6 paginiLipsSam WeaversÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beliefs, Practices, and Reflection: Exploring A Science Teacher's Classroom Assessment Through The Assessment Triangle ModelDocument19 paginiBeliefs, Practices, and Reflection: Exploring A Science Teacher's Classroom Assessment Through The Assessment Triangle ModelNguyễn Hoàng DiệpÎncă nu există evaluări

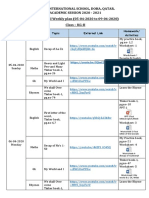

- Loyola International School, Doha, Qatar. Academic Session 2020 - 2021 Home-School Weekly Plan (05-04-2020 To 09-04-2020) Class - KG-IIDocument3 paginiLoyola International School, Doha, Qatar. Academic Session 2020 - 2021 Home-School Weekly Plan (05-04-2020 To 09-04-2020) Class - KG-IIAvik KunduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Renaissance Counterpoit Acoording To ZarlinoDocument8 paginiRenaissance Counterpoit Acoording To ZarlinoAnonymous Ytzo9Jdtk100% (2)

- School Health ServicesDocument56 paginiSchool Health Servicessunielgowda80% (5)