Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Lecture 4 Nematodes

Încărcat de

Ann Michelle TarrobagoDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Lecture 4 Nematodes

Încărcat de

Ann Michelle TarrobagoDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

INTESTINAL NEMATODES

I.

Ascaris lumbricoides

A. Epidemiology: Worldwide. 1 billion people infected. U.S. incidence is highest in the southeast (warm, moist climate).

B. Mode of transmission:

Ingestion of food/water contaminated with embryonated oocysts (eggs mature in the soil). Thousands of eggs can be laid by the worms daily; these are passed in the feces of infected hosts.

C. Clinical manifestations: Ascariasis

1. Mostly asymptomatic. Heavy adult worm burden in the intestines may cause malnutrition. These are the largest of the Nematodes, growing up to 25 cm or more; however, intestinal obstruction is rare.

2. Migration of larvae causes the most morbidity. Lung is the major destination for migrating larvae. Ascaris pneumonia with fever, cough and eosinophilia may occur with heavy larval burden.

D. Pathology: 1. Ingested eggs release larvae; larvae leave the small intestine by penetrating the wall and escaping into the circulatory system. Larvae travel to the lung, cross the alveoli and are coughed up and swallowed.

2. Once back in the small intestine, larvae mature into adult worms that live in the lumen and derive nutrients from hosts digestive process. No attachment of penetration of the adult worms occurs.

E. Laboratory diagnosis: Microscopic examination stool sample for eggs having the characteristic irregular surface.

F. Treatment:

Mebendazole and pyrantel pamoate.

II. Trichuris trichuria: Causes whipworm infection. Humans are the definitive hosts.

A. Epidemiology:

Occurs worldwide, mainly in the tropics and subtropics.

B. Mode of transmission: contaminated soil, food, etc.

Same as for Ascaris: ingestion of fecally-

C. Clinical manifestations: Mostly asymptomatic. Rarely (with heavy infections) whipworm may produce mild anemia, abdominal pain, diarrhea and rectal prolapse

D. Pathology: Eggs develop into immature forms in the small intestine and migrate to the cecum and ascending colon. Here they mature, and produce thousands of eggs which are passed in the feces. Adult worms bury their hairlike anterior ends into the intestinal mucosa, which may cause localized inflammation.

Microscopic examination of stool sample for the E. Laboratory diagnosis: presence of barrel-shaped eggs, each polar plugs.

F. Treatment:

Mebendazole.

III.

Enterobius vermicularis also known as pinworm

A. Epidemiology: Worldwide distribution, especially in the temperate zones. 350 million infected worldwide. Particularly common among children and institutionalized individuals. Can spread among family members.

B. Mode of transmission: Ingestion of eggs from fingers contaminated by scratching, or through contact with contaminated linens or clothing.

Perianal and perineal pruritis (itching) is the C. Clinical manifestations: most common complaint. Many cases are asymptomatic.

D. Pathology: Eggs mature in hours and remain viable for months in the environment of infected individuals. Adult worms live in the cecum and the female migrates at night to the perianal area to lay eggs. This is the cause of the major symptom, the pruritis.

Eggs are not found in the stools, but are recovered E. Laboratory diagnosis: using the Sellotape slide or Scotch tape method from the perianal region just after rising in the morning. A single exam is about 50% reliable.

F. Treatment: Thiabendazole. Eggs are not killed, so retreatment after 2 weeks is advisable. Family members should be treated concomitantly. Reinfection is common.

IV. Strongyloides stercoralis

A. Epidemiology: Worldwide in the tropics and subtropics; southeastern U.S. Patients exposed to Strongyloides in endemic regions may be affected by severe disease produced even after many years if the patient is immunosuppressed.

Direct skin contact with free-living soil larvae B. Mode of transmission: (e.g. walking barefoot). Larvae penetrate the skin and migrate to the lungs.

C. Clinical manifestations: Many cases are asymptomatic. With heavy worm burden, symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, and malabsorption. Massive infection can occur in the immunosuppressed.

D. Pathology:

1.

Larvae are passed in the feces and undergo a free-living phase. Infective (filarial) larvae migrate to the lungs, pass through the alveoli and up the trachea, where they are swallowed. Larvae mature into adults in the small intestine, enter the mucosa and begin producing eggs.

2.

Eggs hatch into rhabditiform larvae in the intestines and are passed in the feces. Autoinfection is caused by rhabditiform larvae that mature without leaving the host and penetrate the intestinal wall to migrate to the lungs. Infection can persist for decades by autoinfection without producing symptoms. Hyperinfection results from an autoinfection cycle in a person whose immunity is compromised by AIDS, T-cell deficiency, or malnutrition.

3.

Direct infection cycles can be set up in which individuals in close contact become infected with the rhabditiform larvae from the primary host without the parasites free-living phase occurring.

Examination of stool samples for the characteristic E. Laboratory diagnosis: rhabditiform larvae. Eosinophilia can be measured by CBC.

F. Treatment:

Thiabendazole.

V.

ecator americanus & Ancylostoma duodenale: Hookworms

A. Epidemiology: Worldwide in the tropics and subtropics; southeastern U.S. . americanus (New World hookworm) and A. duodenale (Old World hookworm)

B. Mode of transmission: Direct skin contact with free-living soil larvae (e.g. walking barefoot). Larvae penetrate the skin and migrate to the lungs.

C. Clinical manifestations: Many cases are asymptomatic. "Ground itch" may occur at the site of larval penetration. Pneumonitis and intestinal malabsorption may occur. Iron deficiency anemia may result from bleeding from the intestinal mucosa.

D. Pathology:

1. Similar to Strongyloides, except that eggs are passed by the infected host and the rhabditiform larvae develop into the filariform larvae as the freeliving phase. Infective filarial larvae migrate to the lungs, pass through the alveoli and up the trachea, where they are swallowed.

2. Larvae develop into adults in the small intestine, attaching to the intestinal wall with either cutting plates ( ecator) or teeth (Ancylostoma). Adults feed on blood from the capillaries of the small intestine. Mechanical injury to the mucosa causes additional blood loss.

Examination of stool samples for the characteristic E. Laboratory diagnosis: thin-shelled eggs. Eosinophilia can be measured by CBC. Anemia is also an indicator.

F. Treatment:

Mebendazole.

DISEASES CAUSED BY NEMATODE LARVAE (Also Called Phasmid Nematodes)

I.

Toxocara sp.: Visceral larva migrans

A. Epidemiology: Worldwide. Eggs from definitive hosts are found in the soil. Children who play in dirt contaminated with animal feces are most at risk.

B. Mode of transmission:

Ingestion of eggs from contaminated soil.

C. Clinical manifestations: Mostly asymptomatic. Symptomatic infections are associated with fever, cough, wheezing (lung symptoms), hepatomegaly, leukocytosis and eosinophilia.

D. Pathology: 1. The definitive host for these parasites is usually a dog or cat. The adult worm lives in the intestine of this host and eggs are passed in the feces, similar to the human cycle with parasites like Trichuris.

2. In humans, ingested eggs release larvae which migrate through tissues causing a host inflammatory response. Granulomatous nodules are typical when the larvae settle in the liver, small intestine, brain and retina. Visceral larva migrans.

E. Laboratory diagnosis: Serologic testing is common. Definitive diagnosis depends upon visualizing the larvae in tissue. Hypergammaglobulinemia and eosinophilia.

F. Treatment:

Diethylcarbamazine.

II.

Ancylostoma braziliense: Cutaneous larva migrans

A. Epidemiology: Worldwide, tropical and subtropical zones. Dog and cat hookworms. Children who play in dirt contaminated with animal feces are most at risk.

B. Mode of transmission:

Exposure of bare skin to contaminated soil.

C. Clinical manifestations: Serpiginous, pruritic lesions of the skin on parts of the body which have contacted the soil.

D. Pathology:

1. The definitive host for these parasites is usually a dog or cat. The adult worm lives in the intestine of this host and eggs are passed in the feces, similar to the human cycle with parasites like ecator americanus.

2. Infective filariform larvae penetrate the skin and migrate through tissues causing an intense host inflammatory response. Itching, redness and swelling associated with the characteristic lesions are the hallmarks of cutaneous larva migrans.

E. Laboratory diagnosis: Diagnosis is made on clinical observation alone. Lesions are very characteristic and the larvae migrate so persistently (0.5 to 1 inch per day) that accurate diagnosis is certain.

F. Treatment: Thiabendazole. Deworming pet dogs and cats and avoiding barefoot travel in infested areas are both good preventative measures.

DISEASES CAUSED BY TISSUE NEMATODES I. Trichinella spiralis: Trichinosis

A. Epidemiology: Worldwide in many carnivores. Among domestic animals, pigs are the most commonly infected, acquiring the infection by feeding on rats or uncooked meat containing cysts. Infection of swine has dropped in the U.S. due to the industrialization of pig farming (i.e., pigs are not feed uncooked garbage).

Ingestion of undercooked meat, usually B. Mode of transmission: pork, containing encysted larvae.

C. Clinical manifestations: Mostly asymptomatic. About 1-2 million people in the U.S. are infected, but there are only about 100 symptomatic cases

reported to the CDC per year. With heavy infection, symptoms include fever, muscle pain, weakness, eosinophilia and periorbital edema. Cardiac or CNS invasion may result in cardiac arrest or respiratory paralysis.

Larvae are released and mature into adult worms in the D. Pathology: small intestine. Eggs hatch within adult females and are released. Larvae are distributed via the bloodstream to various organs, but encyst only within striated muscle. Cysts remain viable for many years, but eventually calcify. Symptomatology usually due to host inflammatory response.

E. Laboratory diagnosis: Muscle biopsy shows larvae within striated muscle. Serologic testing (flocculation) positive 3 weeks postinfection.

Steroids plus mebendazole for extreme cases may be F. Treatment: therapeutic. Generally, no effective therapy. Disease can be prevented by adequately cooking meats.

II. Anisakis species

A. Epidemiology: Worldwide; definitive host is saltwater fish. . The recent increase in popularity of sushi (sashimi) has resulted in increased incidence of this disease in the U.S.

B. Mode of transmission:

Ingestion of inadequately cooked saltwater fish

C. Clinical manifestations: Nausea and vomiting, usually within 24 hours after eating the contaminated fish. Gastroenteritis with blood in the stool may be present. Severe cases may resemble appendicitis or GI cancer (chronic form).

Humans are incidental hosts. Saltwater fish and shellfish are D. Pathology: intermediate hosts; larvae mature into adults in the definitive hosts (marine carnivores). Larvae penetrate the submucosa of the stomach or intestine.

E. Laboratory diagnosis: No serology or treatment available. Surgical removal may be necessary.

DISEASES CAUSED BY BLOOD NEMATODES

I.

Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi: Filariasis

Found in all tropical regions, (Brugia only in certain areas A. Epidemiology: of Asia). Mosquito vector varies. Over 250 million people infected worldwide. Humans are the definitive hosts.

B. Mode of transmission: Female mosquito (esp. Anopheles and Culex sp.) deposits infective larvae on the skin while taking a blood meal. Since the adult worms do not multiply in humans and larvae do not multiply in mosquitoes, disease severity depends on the number larvae-transmitting bites an individual receives.

Early infections are asymptomatic. Later, fever, C. Clinical manifestations: lymphangitis and cellulitis develop. Nocturnal periodicity of microfilariae present in the blood dictates when blood samples are drawn.

D. Pathology: Larvae penetrate the skin and migrate to the lymph nodes. When mature, adults produce microfilariae which circulate in the blood and are ingested by mosquitoes to complete the cycle. Edema in the legs and genitalia results from obstruction. Elephantiasis occurs in patients who have been repeatedly infected over long periods of time.

Thick blood smears (samples drawn at night) E. Laboratory diagnosis: reveal microfilariae. Serologic tests are not useful.

F. Treatment and Prevention: Diethylcarbamazine is only effective against microfilariae (Ivermectin used also). No therapy for adult worms. Prevention involves mosquito control (insecticides, repellents, netting and protective clothing). Disfiguration caused by the edema cannot be reversed.

II. Onchocerca volvulus

A. Epidemiology: people infected.

Africa, Central, and South America. Over 40 million

B. Mode of transmission: The bite of the blackfly transmits infective larvae that migrate into the subcutaneous tissue. Onchocerciasis is also called river blindness because the backflies that transmit the disease develop in rivers and most infected individuals live near these waterways.

Pruritic nodules and papules form due to the C. Clinical manifestations: host inflammatory response to adult worm proteins. Dermatitis, inflammatory lesions such as keratitis, iritis and chorioretinitis and eosinophilia result.

D. Pathology: Female adult worms produce microfilariae that migrate through the subcutaneous tissue. Fibrous nodules develop around the adult worms, especially over the iliac crests. Microfilariae concentrate in the eyes, causing lesions that can lead to blindness. Some lymphatic obstruction has been documented, esp. in Africa. Elephantiasis results.

No serology or blood smears done, since filariae E. Laboratory diagnosis: are never blood-borne. Biopsy of affected skin reveals microfilariae.

F. Treatment and Prevention: Ivermectin is effective against microfilariae. No therapy for adult worms. Prevention involves vector control (insecticides, repellents, netting and protective clothing). Ivermectin is preventative as well.

III. Loa loa

A. Epidemiology:

West and Central Africa; Congo and Niger river basins.

B. Mode of transmission: The bite of the deerfly or mangofly (Chrysops sp.) transmits infective larvae that migrate into the subcutaneous tissue.

C. Clinical manifestations: There is no host inflammatory response to the microfilariae or adults. Transient localized, nonerythematous, nodules (Calabar swellings) form due to host hypersensitivity reaction. Adult worms observed migrating across the conjunctiva is the most dramatic finding.

Female adult worms migrate through the subcutaneous tissue D. Pathology: producing microfilariae. Calabar swellings develop around the adult worms. Microfilariae do not appear in the blood until years after the adult worms appear in some cases. (Maturation time~1 year; lifespan 1-15 years).

E. Laboratory diagnosis: Blood smears from samples collected during the day demonstrate microfilariae. Occasionally biopsy of swellings can recover adults.

Ethylcarbamazine eliminates microfilariae and F. Treatment and Prevention: may kill adults. Ivermectin is effective against microfilariae. Prevention involves vector control (insecticides, repellents, netting and protective clothing).

IV.

Dracunculus medinensis

A. Epidemiology: Tropical regions, especially Africa, the Middle East and India. Most problematic in regions where the same source of water is used for bathing and drinking. Tens of millions people are infected.

Ingestion of contaminated drinking water. B. Mode of transmission: Crustaceans (copepods) containing infective larvae are swallowed. Humans are the definitive hosts.

C. Clinical manifestations:

Causes Guinea Worm Disease.

D. Pathology: Larvae contained within swallowed crustaceans are released, penetrating stomach and small intestine and migrate into the body, where they develop into adults. After maturation and copulation, males die and females migrate to the subcutaneous regions. Females up to a meter long cause the skin to ulcerate due to host inflammatory response. Adult worms produce a

substance that causes blistering and ulceration of the skin, usually of the lower extremities. Motile larvae are released into fresh water when infected hosts bathe or seek the comfort of soaking in water. Infectios larval forms develop in the crustacean host to complete the cycle.

Characteristic presentation of the ulcerated papule. E. Laboratory diagnosis: The head of the worm can sometimes be found within the skin ulcer.

F. Treatment and Prevention: Metronidazole or niridazole aids in making the worm easier to extract, but does not eradicate the worms. Adult worms can be physically removed by winding onto a stick. Disease can be prevented by boiling or filtering drinking water.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Overview of PNIDocument23 paginiOverview of PNIAnn Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To OrthopaedicsDocument53 paginiIntroduction To OrthopaedicsAnn Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pathophysiology (Risk Factors & Symptoms)Document20 paginiPathophysiology (Risk Factors & Symptoms)Ann Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- CBC - Blood Test Used To Evaluate YourDocument8 paginiCBC - Blood Test Used To Evaluate YourAnn Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maternal and Child Nursing QuestionsDocument87 paginiMaternal and Child Nursing QuestionsAnn Michelle Tarrobago50% (2)

- Morality and Ethics - BasicsDocument23 paginiMorality and Ethics - BasicsAnn Michelle Tarrobago50% (2)

- Maternal and Child Nursing Answers and RationaleDocument94 paginiMaternal and Child Nursing Answers and RationaleAnn Michelle Tarrobago100% (1)

- Definition of DXDocument2 paginiDefinition of DXAnn Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elements of PoetryDocument14 paginiElements of PoetryAnn Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gastroenteritis Bronchopneumonia Ear InfectionDocument34 paginiGastroenteritis Bronchopneumonia Ear InfectionAnn Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conflict ManagementDocument7 paginiConflict ManagementAnn Michelle Tarrobago100% (1)

- NCLEX Review About Immune System Disorders 24Document12 paginiNCLEX Review About Immune System Disorders 24Ann Michelle Tarrobago67% (3)

- NCLEX Test CVA, Neuro 24Document19 paginiNCLEX Test CVA, Neuro 24Ann Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- CANCER NSG QuestionsDocument43 paginiCANCER NSG QuestionsAnn Michelle Tarrobago83% (6)

- Postpartum Health TeachingDocument6 paginiPostpartum Health TeachingAnn Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tramadol Drug StudyDocument3 paginiTramadol Drug StudyAnn Michelle Tarrobago100% (1)

- Divorce in The PhilippinesDocument3 paginiDivorce in The PhilippinesAnn Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sorry Wrong Number by Lucille FletcherDocument25 paginiSorry Wrong Number by Lucille FletcherAnn Michelle Tarrobago100% (6)

- Addition Rules For ProbabilityDocument11 paginiAddition Rules For ProbabilityAnn Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Reactions of The Citric Acid CycleDocument3 paginiThe Reactions of The Citric Acid CycleAnn Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epidural AnesthesiaDocument7 paginiEpidural AnesthesiaAnn Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- ARES Protocol Os UseDocument5 paginiARES Protocol Os UseLeia AlbaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medical Symptoms QuestionnaireDocument29 paginiMedical Symptoms QuestionnaireOlesiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- COMPLICATII TARDIVE DUPA INJECTAREA DE ACID HIALURONIC IN SCOP ESTETIC SI MANAGEMENTUL LOR Ro 399Document21 paginiCOMPLICATII TARDIVE DUPA INJECTAREA DE ACID HIALURONIC IN SCOP ESTETIC SI MANAGEMENTUL LOR Ro 399tzupel4Încă nu există evaluări

- Immnunology Notebook Chapter One: Innate ImmunityDocument45 paginiImmnunology Notebook Chapter One: Innate ImmunityJavier Alejandro Daza GalvánÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cancer Ozone Therapy Treatment A DiscussionDocument13 paginiCancer Ozone Therapy Treatment A DiscussionjpgbfÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aatru Medical Announces FDA Clearance and Commercial Launch of The NPSIMS™ - Negative Pressure Surgical Incision Management SystemDocument4 paginiAatru Medical Announces FDA Clearance and Commercial Launch of The NPSIMS™ - Negative Pressure Surgical Incision Management SystemPR.comÎncă nu există evaluări

- Axa Group Corporate PresentationDocument35 paginiAxa Group Corporate PresentationRajneesh VermaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study 5 Dengue Fever CorrectedDocument13 paginiCase Study 5 Dengue Fever CorrectedyounggirldavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Standard Coding Guideline ICD-10-TM 2006Document192 paginiStandard Coding Guideline ICD-10-TM 2006api-3835927100% (1)

- D An Introduction: Physical Medicine and RehabilitationDocument33 paginiD An Introduction: Physical Medicine and RehabilitationChadÎncă nu există evaluări

- CortisolDocument27 paginiCortisolCao YunÎncă nu există evaluări

- Newborn CareDocument19 paginiNewborn CareYa Mei LiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Che 225 Control of Communicable DiseasesDocument19 paginiChe 225 Control of Communicable DiseasesAbdullahi Bashir SalisuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Haematology Paper 1 - Past PapersDocument9 paginiHaematology Paper 1 - Past Papersmma1976100% (1)

- Guide PDFDocument84 paginiGuide PDFbiomeditechÎncă nu există evaluări

- SP42 Thoracentesis (Adult)Document7 paginiSP42 Thoracentesis (Adult)Adam HuzaibyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Student Excursion Consent FormDocument4 paginiStudent Excursion Consent Formapi-276186998Încă nu există evaluări

- ShockDocument53 paginiShockHassan Ahmed100% (3)

- Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating PolyradiculoneuropathyDocument5 paginiChronic Inflammatory Demyelinating PolyradiculoneuropathyDiego Fernando AlegriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- All About Rabies Health ScienceDocument28 paginiAll About Rabies Health SciencetototoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Surgical Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux in Adults - UpToDateDocument22 paginiSurgical Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux in Adults - UpToDateJuan InsignaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Editorial: Dental Caries and OsteoporosisDocument2 paginiEditorial: Dental Caries and OsteoporosisBagis Emre GulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pedia Nursing Resource Unit - FinalDocument69 paginiPedia Nursing Resource Unit - FinalDaryl Adrian RecaidoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Renr Practice Test 7 FinalDocument13 paginiRenr Practice Test 7 FinalTk100% (1)

- Travatan (Travoprost Ophthalmic Solution) 0.004% SterileDocument7 paginiTravatan (Travoprost Ophthalmic Solution) 0.004% SterileSyed Shariq AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medication AdministrationDocument8 paginiMedication AdministrationMarku LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

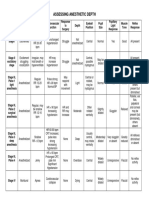

- Anesthesia-Assessing Depth PDFDocument1 paginăAnesthesia-Assessing Depth PDFAvinash Technical ServiceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sheet 2 (Local Anesthesia 2)Document14 paginiSheet 2 (Local Anesthesia 2)ardesh abdilleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Venous Thromboembolism in Patients Discharged From The Emergency Department With Ankle FracturesDocument13 paginiVenous Thromboembolism in Patients Discharged From The Emergency Department With Ankle FracturesSebastiano Della CasaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treating Canine Distemper VirusDocument23 paginiTreating Canine Distemper VirusJack HollandÎncă nu există evaluări