Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

D. H. Lawrence - The Rocking-Horse Winner

Încărcat de

LenaDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

D. H. Lawrence - The Rocking-Horse Winner

Încărcat de

LenaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

THE ROCKING-HORSE WINNER D. H.

Lawrence There was a woman who was beautiful, who started with all the advantages, yet she had no luck. She married for love, and the love turned to dust. She had bonny children, yet she felt they had been thrust upon her, and she could not love them. They looked at her coldly, as if they were finding fault with her. And hurriedly she felt she must cover up some fault in herself. et what it was that she must cover up she never knew. !evertheless, when her children were present, she always felt the centre of her heart go hard. This troubled her, and in her manner she was all the more gentle and an"ious for her children, as if she loved them very much. #nly she herself knew that at the centre of her heart was a hard little place that could not feel love, no, not for anybody. $verybody else said of her% &She is such a good mother. She adores her children.& #nly she herself, and her children themselves, knew it was not so. They read it in each other's eyes. There were a boy and two little girls. They lived in a pleasant house, with a garden, and they had discreet servants, and felt themselves superior to anyone in the neighbourhood. Although they lived in style, they felt always an an"iety in the house. There was never enough money. The mother had a small income, and the father had a small income, but not nearly enough for the social position which they had to keep up. The father went in to town to some office. (ut though he had good prospects, these prospects never materialised. There was always the grinding sense of the shortage of money, though the style was always kept up. At last the mother said, &) will see if I can't make something.& (ut she did not know where to begin. She racked her brains, and tried this thing and the other, but could not find anything successful. The failure made deep lines come into her face. Her children were growing up, they would have to go to school. There must be more money, there must be more money. The father, who was always very handsome and e"pensive in his tastes, seemed as if he never would be able to do anything worth doing. And the mother, who had a great belief in herself, did not succeed any better, and her tastes were *ust as e"pensive. And so the house came to be haunted by the unspoken phrase% There must be more money! There must be more money! The children could hear it all the time, though nobody said it aloud. They heard it at +hristmas, when the e"pensive and splendid toys filled the nursery. (ehind the shining modern rocking,horse, behind the smart doll's, house, a voice would start whispering% &There must be more money- There must be more money-& And the children would stop playing, to listen for a moment. They would look into each other's eyes, to see if they had all heard. And each one saw in the eyes of the other two that they too had heard. &There must be more money- There must be more money-& )t came whispering from the springs of the still,swaying rocking,horse, and even the horse, bending his wooden, champing head, heard it. The big doll, sitting so pink and smirking in her new pram, could hear it .uite plainly, and seemed to be smirking all the more self,consciously because of it. The foolish puppy, too, that took the place of the

teddy,bear, he was looking so e"traordinarily foolish for no other reason but that he heard the secret whisper all over the house% &There must be more money.& et nobody ever said it aloud. The whisper was everywhere, and therefore no one spoke it. /ust as no one ever says% &0e are breathing-& in spite of the fact that breath is coming and going all the time. &1other-& said the boy 2aul one day. &0hy don't we keep a car of our own3 0hy do we always use uncle's, or else a ta"i3& &(ecause we're the poor members of the family,& said the mother. &(ut why are we, mother3& &0ell,,) suppose,& she said slowly and bitterly, &it's because your father has no luck.& The boy was silent for some time. &)s luck money, mother3& he asked, rather timidly. &!o, 2aul- !ot .uite. )t's what causes you to have money.& &#h-& said 2aul vaguely. &) thought when 4ncle #scar said filthy lucker, it meant money.& &Filthy lucre does mean money,& said the mother. &(ut it's lucre, not luck.& &#h-& said the boy. &Then what is luck, mother3& &)t's what causes you to have money. )f you're lucky you have money. That's why it's better to be born lucky than rich. )f you're rich, you may lose your money. (ut if you're lucky, you will always get more money.& &#h- 0ill you- And is father not lucky3& &5ery unlucky, ) should say,& she said bitterly. The boy watched her with unsure eyes. &0hy3& he asked. &) don't know. !obody ever knows why one person is lucky and another unlucky.& &Don't they3 !obody at all3 Does nobody know3& &2erhaps 6od- (ut He never tells.& &He ought to, then. And aren't you lucky either, mother3& &) can't be, if ) married an unlucky husband.& &(ut by yourself, aren't you3& &) used to think ) was, before ) married. !ow ) think ) am very unlucky indeed.& &0hy3& &0ell,,never mind- 2erhaps )'m not really,& she said. The child looked at her, to see if she meant it. (ut he saw, by the lines of her mouth, that she was only trying to hide something from him. &0ell, anyhow,& he said stoutly, &)'m a lucky person.& &0hy3& said his mother, with a sudden laugh. He stared at her. He didn't even know why he had said it. &6od told me,& he asserted, bra7ening it out. &) hope He did, dear-& she said, again with a laugh, but rather bitter. &He did, mother-& &$"cellent-& said the mother, using one of her husband's e"clamations. The boy saw she did not believe him8 or rather, that she paid no attention to his assertion. This angered him somewhere, and made him want to compel her attention. He went off by himself, vaguely, in a childish way, seeking for the clue to &luck&. Absorbed, taking no heed of other people, he went about with a sort of stealth, seeking

inwardly for luck. He wanted luck, he wanted it, he wanted it. 0hen the two girls were playing dolls, in the nursery, he would sit on his big rocking,horse, charging madly into space, with a fren7y that made the little girls peer at him uneasily. 0ildly the horse careered, the waving dark hair of the boy tossed, his eyes had a strange glare in them. The little girls dared not speak to him. 0hen he had ridden to the end of his mad little *ourney, he climbed down and stood in front of his rocking,horse, staring fi"edly into its lowered face. )ts red mouth was slightly open, its big eye was wide and glassy bright. &!ow-& he would silently command the snorting steed. &!ow take me to where there is luck- !ow take me-& And he would slash the horse on the neck with the little whip he had asked 4ncle #scar for. He knew the horse could take him to where there was luck, if only he forced it. So he would mount again, and start on his furious ride, hoping at last to get there. He knew he could get there. & ou'll break your horse, 2aul-& said the nurse. &He's always riding like that- ) wish he'd leave off-& said his elder sister /oan. (ut he only glared down on them in silence. !urse gave him up. She could make nothing of him. Anyhow he was growing beyond her. #ne day his mother and his 4ncle #scar came in when he was on one of his furious rides. He did not speak to them. &Hallo- you young *ockey- 9iding a winner3& said his uncle. &Aren't you growing too big for a rocking,horse3 ou're not a very little boy any longer, you know,& said his mother. (ut 2aul only gave a blue glare from his big, rather close,set eyes. He would speak to nobody when he was in full tilt. His mother watched him with an an"ious e"pression on her face. At last he suddenly stopped forcing his horse into the mechanical gallop, and slid down. &0ell, ) got there-& he announced fiercely, his blue eyes still flaring, and his sturdy long legs straddling apart. &0here did you get to3& asked his mother. &0here ) wanted to go to,& he flared back at her. &That's right, son-& said 4ncle #scar. &Don't you stop till you get there. 0hat's the horse's name3& &He doesn't have a name,& said the boy. &6ets on without all right3& asked the uncle. &0ell, he has different names. He was called Sansovino last week.& &Sansovino, eh3 0on the Ascot. How did you know his name3& &He always talks about horse,races with (assett,& said /oan. The uncle was delighted to find that his small nephew was posted with all the racing news. (assett, the young gardener who had been wounded in the left foot in the war, and had got his present *ob through #scar +resswell, whose batman he had been, was a perfect blade of the &turf&. He lived in the racing events, and the small boy lived with him. #scar +resswell got it all from (assett.

&1aster 2aul comes and asks me, so ) can't do more than tell him, sir,& said (assett, his face terribly serious, as if he were speaking of religious matters. &And does he ever put anything on a horse he fancies3& &0ell,,) don't want to give him away,,he's a young sport, a fine sport, sir. 0ould you mind asking him himself3 He sort of takes a pleasure in it, and perhaps he'd feel ) was giving him away, sir, if you don't mind.& (assett was serious as a church. The uncle went back to his nephew, and took him off for a ride in the car. &Say, 2aul, old man, do you ever put anything on a horse3& the uncle asked. The boy watched the handsome man closely. &0hy, do you think ) oughtn't to3& he parried. &!ot a bit of it- ) thought perhaps you might give me a tip for the Lincoln.& The car sped on into the country, going down to 4ncle #scar's place in Hampshire. &Honour bright3& said the nephew. &Honour bright, son-& said the uncle. &0ell, then, Daffodil.& &Daffodil- ) doubt it, sonny. 0hat about 1ir7a3& &) only know the winner,& said the boy. &That's Daffodil-& &Daffodil, eh3& There was a pause. Daffodil was an obscure horse comparatively. &4ncle-& & es, son3& & ou won't let it go any further, will you3 ) promised (assett.& &(assett be damned, old man- 0hat's he got to do with it3& &0e're partners- 0e've been partners from the first- 4ncle, he lent me my first five shillings, which ) lost. ) promised him, honour bright, it was only between me and him% only you gave me that ten,shilling note ) started winning with, so ) thought you were lucky. ou won't let it go any further, will you3& The boy ga7ed at his uncle from those big, hot, blue eyes, set rather close together. The uncle stirred and laughed uneasily. &9ight you are, son- )'ll keep your tip private. Daffodil, eh- How much are you putting on him3& &All e"cept twenty pounds,& said the boy. &) keep that in reserve.& The uncle thought it a good *oke. & ou keep twenty pounds in reserve, do you, you young romancer3 0hat are you betting, then3& &)'m betting three hundred,& said the boy gravely. &(ut it's between you and me, 4ncle #scar- Honour bright3& The uncle burst into a roar of laughter. &)t's between you and me all right, you young !at 6ould,& he said, laughing. &(ut where's your three hundred3& &(assett keeps it for me. 0e're partners.& & ou are, are you- And what is (assett putting on Daffodil3& &He won't go .uite as high as ) do, ) e"pect. 2erhaps he'll go a hundred and fifty.& &0hat, pennies3& laughed the uncle. &2ounds,& said the child, with a surprised look at his uncle. &(assett keeps a bigger reserve than ) do.&

(etween wonder and amusement, 4ncle #scar was silent. He pursued the matter no further, but he determined to take his nephew with him to the Lincoln races. &!ow, son,& he said, &)'m putting twenty on 1ir7a, and )'ll put five for you on any horse you fancy. 0hat's your pick3& &Daffodil, uncle-& &!o, not the fiver on Daffodil-& &) should if it was my own fiver,& said the child. &6ood- 6ood- 9ight you are- A fiver for me and a fiver for you on Daffodil.& The child had never been to a race,meeting before, and his eyes were blue fire. He pursed his mouth tight, and watched. A :renchman *ust in front had put his money on Lancelot. 0ild with e"citement, he flayed his arms up and down, yelling 'Lancelot! Lancelot;' in his :rench accent. Daffodil came in first, Lancelot second, 1ir7a third. The child, flushed and with eyes bla7ing, was curiously serene. His uncle brought him five five,pound notes% four to one. &0hat am ) to do with these3& he cried, waving them before the boy's eyes. &) suppose we'll talk to (assett,& said the boy. &) e"pect ) have fifteen hundred now% and twenty in reserve% and this twenty.& His uncle studied him for some moments. &Look here, son-& he said. & ou're not serious about (assett and that fifteen hundred, are you3& & es, ) am. (ut it's between you and me, uncle- Honour bright-& &Honour bright all right, son- (ut ) must talk to (assett.& &)f you'd like to be a partner, uncle, with (assett and me, we could all be partners. #nly you'd have to promise, honour bright, uncle, not to let it go beyond us three. (assett and ) are lucky, and you must be lucky, because it was your ten shillings ) started winning with . . .& 4ncle #scar took both (assett and 2aul into 9ichmond 2ark for an afternoon, and there they talked. &)t's like this, you see, sir,& (assett said. &1aster 2aul would get me talking about racing events, spinning yarns, you know, sir. And he was always keen on knowing if )'d made or if )'d lost. )t's about a year since, now, that ) put five shillings on (lush of Dawn for him% and we lost. Then the luck turned, with that ten shillings he had from you% that we put on Singhalese. And since that time, it's been pretty steady, all things considering. 0hat do you say, 1aster 2aul3& &0e're all right when we're sure,& said 2aul. &)t's when we're not .uite sure that we go down.& &#h, but we're careful then,& said (assett. &(ut when are you sure3& smiled 4ncle #scar. &)t's 1aster 2aul, sir,& said (assett, in a secret, religious voice. &)t's as if he had it from heaven. Like Daffodil now, for the Lincoln. That was as sure as eggs.& &Did you put anything on Daffodil3& asked #scar +resswell. & es, sir. ) made my bit.& &And my nephew3& (assett was obstinately silent, looking at 2aul. &) made twelve hundred, didn't ), (assett3 ) told uncle ) was putting three hundred on Daffodil.&

&That's right,& said (assett, nodding. &(ut where's the money3& asked the uncle. &) keep it safe locked up, sir. 1aster 2aul, he can have it any minute he likes to ask for it.& &0hat, fifteen hundred pounds3& &And twenty- And forty, that is, with the twenty he made on the course.& &)t's ama7ing-& said the uncle. &)f 1aster 2aul offers you to be partners, sir, ) would, if ) were you% if you'll e"cuse me,& said (assett. #scar +resswell thought about it. &)'ll see the money,& he said. They drove home again, and sure enough, (assett came round to the garden,house with fifteen hundred pounds in notes. The twenty pounds reserve was left with /oe 6lee, in the Turf +ommission deposit. & ou see, it's all right, uncle, when )'m sure- Then we go strong, for all we're worth. Don't we, (assett3& &0e do that, 1aster 2aul.& &And when are you sure3& said the uncle, laughing. &#h, well, sometimes )'m absolutely sure, like about Daffodil,& said the boy8 &and sometimes ) have an idea8 and sometimes ) haven't even an idea, have ), (assett3 Then we're careful, because we mostly go down.& & ou do, do you- And when you're sure, like about Daffodil, what makes you sure, sonny3& &#h, well, ) don't know,& said the boy uneasily. &)'m sure, you know, uncle8 that's all.& &)t's as if he had it from heaven, sir,& (assett reiterated. &) should say so-& said the uncle. (ut he became a partner. And when the Leger was coming on, 2aul was &sure& about Lively Spark, which was a .uite inconsiderable horse. The boy insisted on putting a thousand on the horse, (assett went for five hundred, and #scar +resswell two hundred. Lively Spark came in first, and the betting had been ten to one against him. 2aul had made ten thousand. & ou see,& he said, &) was absolutely sure of him.& $ven #scar +resswell had cleared two thousand. &Look here, son,& he said, &this sort of thing makes me nervous.& &)t needn't, uncle- 2erhaps ) shan't be sure again for a long time.& &(ut what are you going to do with your money3& asked the uncle. &#f course,& said the boy, &) started it for mother. She said she had no luck, because father is unlucky, so ) thought if I was lucky, it might stop whispering.& &0hat might stop whispering3& &#ur house- ) hate our house for whispering.& &0hat does it whisper3& &0hy,,why&,,the boy fidgeted,,&why, ) don't know- (ut it's always short of money, you know, uncle.& &) know it, son, ) know it.& & ou know people send mother writs, don't you, uncle3& &)'m afraid ) do,& said the uncle.

&And then the house whispers like people laughing at you behind your back. )t's awful, that is- ) thought if ) was lucky,,& & ou might stop it,& added the uncle. The boy watched him with big blue eyes, that had an uncanny cold fire in them, and he said never a word. &0ell then-& said the uncle. &0hat are we doing3& &) shouldn't like mother to know ) was lucky,& said the boy. &0hy not, son3& &She'd stop me.& &) don't think she would.& &#h-&,,and the boy writhed in an odd way,,&) don't want her to know, uncle.& &All right, son- 0e'll manage it without her knowing.& They managed it very easily. 2aul, at the other's suggestion, handed over five thousand pounds to his uncle, who deposited it with the family lawyer, who was then to inform 2aul's mother that a relative had put five thousand pounds into his hands, which sum was to be paid out a thousand pounds at a time, on the mother's birthday, for the ne"t five years. &So she'll have a birthday present of a thousand pounds for five successive years,& said 4ncle #scar. &) hope it won't make it all the harder for her later.& 2aul's mother had her birthday in !ovember. The house had been &whispering& worse than ever lately, and even in spite of his luck, 2aul could not bear up against it. He was very an"ious to see the effect of the birthday letter, telling his mother about the thousand pounds. 0hen there were no visitors, 2aul now took his meals with his parents, as he was beyond the nursery control. His mother went into town nearly every day. She had discovered that she had an odd knack of sketching furs and dress materials, so she worked secretly in the studio of a friend who was the chief &artist& for the leading drapers. She drew the figures of ladies in furs and ladies in silk and se.uins for the newspaper advertisements. This young woman artist earned several thousand pounds a year, but 2aul's mother only made several hundreds, and she was again dissatisfied. She so wanted to be first in something, and she did not succeed, even in making sketches for drapery advertisements. She was down to breakfast on the morning of her birthday. 2aul watched her face as she read her letters. He knew the lawyer's letter. As his mother read it, her face hardened and became more e"pressionless. Then a cold, determined look came on her mouth. She hid the letter under the pile of others, and said not a word about it. &Didn't you have anything nice in the post for your birthday, mother3& said 2aul. &<uite moderately nice,& she said, her voice cold and absent. She went away to town without saying more. (ut in the afternoon 4ncle #scar appeared. He said 2aul's mother had had a long interview with the lawyer, asking if the whole five thousand could not be advanced at once, as she was in debt. &0hat do you think, uncle3& said the boy. &) leave it to you, son.& &#h, let her have it, then- 0e can get some more with the other,& said the boy. &A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, laddie-& said 4ncle #scar.

&(ut )'m sure to know for the 6rand !ational8 or the Lincolnshire8 or else the Derby. )'m sure to know for one of them,& said 2aul. So 4ncle #scar signed the agreement, and 2aul's mother touched the whole five thousand. Then something very curious happened. The voices in the house suddenly went mad, like a chorus of frogs on a spring evening. There were certain new furnishings, and 2aul had a tutor. He was really going to $ton, his father's school, in the following autumn. There were flowers in the winter, and a blossoming of the lu"ury 2aul's mother had been used to. And yet the voices in the house, behind the sprays of mimosa and almond,blossom, and from under the piles of iridescent cushions, simply trilled and screamed in a sort of ecstasy% &There must be more money- #h,h,h- There must be more money- #h, now, now,w- now,w,w,,there must be more money-,,more than ever- 1ore than ever-& )t frightened 2aul terribly. He studied away at his Latin and 6reek with his tutors. (ut his intense hours were spent with (assett. The 6rand !ational had gone by% he had not &known&, and had lost a hundred pounds. Summer was at hand. He was in agony for the Lincoln. (ut even for the Lincoln he didn't &know&, and he lost fifty pounds. He became wild,eyed and strange, as if something were going to e"plode in him. &Let it alone, son- Don't you bother about it-& urged 4ncle #scar. (ut it was as if the boy couldn't really hear what his uncle was saying. &)'ve got to know for the Derby- )'ve got to know for the Derby-& the child reiterated, his big blue eyes bla7ing with a sort of madness. His mother noticed how overwrought he was. & ou'd better go to the seaside. 0ouldn't you like to go now to the seaside, instead of waiting3 ) think you'd better,& she said, looking down at him an"iously, her heart curiously heavy because of him. (ut the child lifted his uncanny blue eyes. &) couldn't possibly go before the Derby, mother-& he said. &) couldn't possibly-& &0hy not3& she said, her voice becoming heavy when she was opposed. &0hy not3 ou can still go from the seaside to see the Derby with your 4ncle #scar, if that's what you wish. !o need for you to wait here. (esides, ) think you care too much about these races. )t's a bad sign. 1y family has been a gambling family, and you won't know till you grow up how much damage it has done. (ut it has done damage. ) shall have to send (assett away, and ask 4ncle #scar not to talk racing to you, unless you promise to be reasonable about it% go away to the seaside and forget it. ou're all nerves-& &)'ll do what you like, mother, so long as you don't send me away till after the Derby,& the boy said. &Send you away from where3 /ust from this house3& & es,& he said, ga7ing at her. &0hy, you curious child, what makes you care about this house so much, suddenly3 ) never knew you loved it-& He ga7ed at her without speaking. He had a secret within a secret, something he had not divulged, even to (assett or to his 4ncle #scar. (ut his mother, after standing undecided and a little bit sullen for some moments, said%

&5ery well, then- Don't go to the seaside till after the Derby, if you don't wish it. (ut promise me you won't let your nerves go to pieces- 2romise you won't think so much about horse,racing and events, as you call them-& &#h no-& said the boy, casually. &) won't think much about them, mother. ou needn't worry. ) wouldn't worry, mother, if ) were you.& &)f you were me and ) were you,& said his mother, &) wonder what we should do-& &(ut you know you needn't worry, mother, don't you3& the boy repeated. &) should be awfully glad to know it,& she said wearily. &#h, well, you can, you know. ) mean you ought to know you needn't worry-& he insisted. &#ught )3 Then )'ll see about it,& she said. 2aul's secret of secrets was his wooden horse, that which had no name. Since he was emancipated from a nurse and a nursery governess, he had had his rocking,horse removed to his own bedroom at the top of the house. &Surely you're too big for a rocking,horse-& his mother had remonstrated. &0ell, you see, mother, till ) can have a real horse, ) like to have some sort of animal about,& had been his .uaint answer. &Do you feel he keeps you company3& she laughed. &#h yes- He's very good, he always keeps me company, when )'m there,& said 2aul. So the horse, rather shabby, stood in an arrested prance in the boy's bedroom. The Derby was drawing near, and the boy grew more and more tense. He hardly heard what was spoken to him, he was very frail, and his eyes were really uncanny. His mother had sudden strange sei7ures of uneasiness about him. Sometimes, for half an hour, she would feel a sudden an"iety about him that was almost anguish. She wanted to rush to him at once, and know he was safe. Two nights before the Derby, she was at a big party in town, when one of her rushes of an"iety about her boy, her first,born, gripped her heart till she could hardly speak. She fought with the feeling, might and main, for she believed in common,sense. (ut it was too strong. She had to leave the dance and go downstairs to telephone to the country. The children's nursery governess was terribly surprised and startled at being rung up in the night. &Are the children all right, 1iss 0ilmot3& &#h yes, they are .uite all right.& &1aster 2aul3 )s he all right3& &He went to bed as right as a trivet. Shall ) run up and look at him3& &!o-& said 2aul's mother reluctantly. &!o- Don't trouble. )t's all right. Don't sit up. 0e shall be home fairly soon.& She did not want her son's privacy intruded upon. &5ery good,& said the governess. )t was about one o'clock when 2aul's mother and father drove up to their house. All was still. 2aul's mother went to her room and slipped off her white fur cloak. She had told her maid not to wait up for her. She heard her husband downstairs, mi"ing a whisky,and, soda. And then, because of the strange an"iety at her heart, she stole upstairs to her son's room. !oiselessly she went along the upper corridor. 0as there a faint noise3 0hat was it3

She stood, with arrested muscles, outside his door, listening. There was a strange, heavy, and yet not loud noise. Her heart stood still. )t was a soundless noise, yet rushing and powerful. Something huge, in violent, hushed motion. 0hat was it3 0hat in 6od's !ame was it3 She ought to know. She felt that she knew the noise. She knew what it was. et she could not place it. She couldn't say what it was. And on and on it went, like a madness. Softly, fro7en with an"iety and fear, she turned the door,handle. The room was dark. et in the space near the window, she heard and saw something plunging to and fro. She ga7ed in fear and ama7ement. Then suddenly she switched on the light, and saw her son, in his green py*amas, madly surging on his rocking,horse. The bla7e of light suddenly lit him up, as he urged the wooden horse, and lit her up, as she stood, blonde, in her dress of pale green and crystal, in the doorway. &2aul-& she cried. &0hatever are you doing3& &)t's 1alabar-& he screamed, in a powerful, strange voice. &)t's 1alabar-& His eyes bla7ed at her for one strange and senseless second, as he ceased urging his wooden horse. Then he fell with a crash to the ground, and she, all her tormented motherhood flooding upon her, rushed to gather him up. (ut he was unconscious, and unconscious he remained, with some brain,fever. He talked and tossed, and his mother sat stonily by his side. &1alabar- )t's 1alabar- (assett, (assett, ) know: it's 1alabar-& So the child cried, trying to get up and urge the rocking,horse that gave him his inspiration. &0hat does he mean by 1alabar3& asked the heart,fro7en mother. &) don't know,& said the father, stonily. &0hat does he mean by 1alabar3& she asked her brother #scar. &)t's one of the horses running for the Derby,& was the answer. And, in spite of himself, #scar +resswell spoke to (assett, and himself put a thousand on 1alabar% at fourteen to one. The third day of the illness was critical% they were watching for a change. The boy, with his rather long, curly hair, was tossing ceaselessly on the pillow. He neither slept nor regained consciousness, and his eyes were like blue stones. His mother sat, feeling her heart had gone, turned actually into a stone. )n the evening, #scar +resswell did not come, but (assett sent a message, saying could he come up for one moment, *ust one moment3 2aul's mother was very angry at the intrusion, but on second thoughts she agreed. The boy was the same. 2erhaps (assett might bring him to consciousness. The gardener, a shortish fellow with a little brown moustache and sharp little brown eyes, tiptoed into the room, touched his imaginary cap to 2aul's mother, and stole to the bedside, staring with glittering, smallish eyes at the tossing, dying child. &1aster 2aul-& he whispered. &1aster 2aul- 1alabar came in first all right, a clean win. ) did as you told me. ou've made over seventy thousand pounds, you have8 you've got over eighty thousand. 1alabar came in all right, 1aster 2aul.& &1alabar- 1alabar- Did ) say 1alabar, mother3 Did ) say 1alabar3 Do you think )'m lucky, mother3 ) knew 1alabar, didn't )3 #ver eighty thousand pounds- ) call that lucky, don't you, mother3 #ver eighty thousand pounds- ) knew, didn't ) know ) knew3 1alabar

came in all right. )f ) ride my horse till )'m sure, then ) tell you, (asset, you can go as high as you like. Did you go for all you were worth, (assett3& &) went a thousand on it, 1aster 2aul.& &) never told you, mother, that if ) can ride my horse, and get there, then )'m absolutely sure,,oh, absolutely- 1other, did ) ever tell you3 ) am lucky-& &!o, you never did,& said the mother. (ut the boy died in the night. And even as he lay dead, his mother heard her brother's voice saying to her% &1y 6od, Hester, you're eighty,odd thousand to the good, and a poor devil of a son to the bad. (ut, poor devil, poor devil, he's best gone out of a life where he rides his rocking,horse to find a winner.&

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- William Faulkner - A Rose For EmilyDocument7 paginiWilliam Faulkner - A Rose For EmilyLena100% (4)

- Safety & Maintenance Checklist: Vibratory Soil CompactorsDocument1 paginăSafety & Maintenance Checklist: Vibratory Soil CompactorsAal CassanovaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baby Lock Evolve User Manual PDFDocument92 paginiBaby Lock Evolve User Manual PDFNyetÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Pros of Cons (Excerpt)Document41 paginiThe Pros of Cons (Excerpt)I Read YAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bike To WorkDocument112 paginiBike To WorkHamza Patel100% (1)

- PDF BanneredDocument58 paginiPDF BanneredIFabrizioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cutestkidsmom Because of A BoyDocument383 paginiCutestkidsmom Because of A BoyNeramu Yavi100% (1)

- Ancient MosaicsDocument16 paginiAncient Mosaicssegu82100% (5)

- PatolinoDocument11 paginiPatolinocindy100% (1)

- 124 Sta. Ana v. MaliwatDocument2 pagini124 Sta. Ana v. MaliwatNN DDLÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Half-Orc's Maiden Bride by Ruby DixonDocument170 paginiThe Half-Orc's Maiden Bride by Ruby DixonLazyÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Iron ClothesDocument24 paginiHow To Iron ClothesDemie Anne Alviz BerganteÎncă nu există evaluări

- She Wore Red Trainers: A Muslim Love StoryDe la EverandShe Wore Red Trainers: A Muslim Love StoryEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (55)

- The Rocking-Horse WinnerDocument17 paginiThe Rocking-Horse Winneralextuber 123Încă nu există evaluări

- D H Lawrence - A Short Story Collection - Volume 2: A titan of English literature that challenged ideas of romance and sexualityDe la EverandD H Lawrence - A Short Story Collection - Volume 2: A titan of English literature that challenged ideas of romance and sexualityÎncă nu există evaluări

- D H Lawrence - A Short Story Collection - Volume 2: “It’s what causes you to have money''De la EverandD H Lawrence - A Short Story Collection - Volume 2: “It’s what causes you to have money''Încă nu există evaluări

- Rocking-Horse-Winner Short StoryDocument13 paginiRocking-Horse-Winner Short StoryFlorenciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rocking Horse Winner IntermediateDocument13 paginiRocking Horse Winner Intermediatedarkkitten76Încă nu există evaluări

- Pride and PrejudiceDocument214 paginiPride and PrejudiceViktoryia ShcharbininaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Doll House - John HuntDocument209 paginiDoll House - John HuntRoxana ElenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book BoundDocument83 paginiBook BoundJullier E. RuizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sliced and Diced 3: Another 13 Dark and Twisted Short StoriesDe la EverandSliced and Diced 3: Another 13 Dark and Twisted Short StoriesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sliced and Diced 3: Sliced and Diced Collections, #3De la EverandSliced and Diced 3: Sliced and Diced Collections, #3Încă nu există evaluări

- WWW - Twilight-:, Chapter 2Document4 paginiWWW - Twilight-:, Chapter 2Yram Chuy Ü DiodocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shame by Dick GregoryDocument5 paginiShame by Dick Gregoryapi-266910774Încă nu există evaluări

- A Magic Journey to Things Past: Mirela’s … Once Upon a TimeDe la EverandA Magic Journey to Things Past: Mirela’s … Once Upon a TimeÎncă nu există evaluări

- SOCI129 Lec Notes 7Document3 paginiSOCI129 Lec Notes 7Trisha EstremeraÎncă nu există evaluări

- History's Royal Highnesses Cinderella: Complete SeriesDe la EverandHistory's Royal Highnesses Cinderella: Complete SeriesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jack Beltane: The Hits So FarDocument118 paginiJack Beltane: The Hits So FarJack BeltaneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ebook Chemistry Class 9 PDF Full Chapter PDFDocument67 paginiEbook Chemistry Class 9 PDF Full Chapter PDFrobert.davidson233100% (22)

- Cerita Sangkuriang Dan Maling KundangDocument3 paginiCerita Sangkuriang Dan Maling KundangFormat Seorang LegendaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Under the Circumstances: How to Meet Celebrities Without Leaving HomeDe la EverandUnder the Circumstances: How to Meet Celebrities Without Leaving HomeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Doll by Emidio EnriquezDocument5 paginiThe Doll by Emidio EnriquezArlene RiofloridoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adjectives Describing PeopleDocument7 paginiAdjectives Describing PeopleLenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prva 4 PrevodaDocument4 paginiPrva 4 PrevodaLenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adjectives Describing PeopleDocument7 paginiAdjectives Describing PeopleLenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edgar Wallace - Discovering RexDocument10 paginiEdgar Wallace - Discovering RexLenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Give Successful PresentationDocument3 paginiHow To Give Successful PresentationLenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MARINEL LEARNING PLAN IN TLE NDDocument12 paginiMARINEL LEARNING PLAN IN TLE NDmark jay legoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Belford W DissertationDocument197 paginiBelford W DissertationAllison V. MoffettÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Stylistics - The BestDocument214 paginiIntroduction To Stylistics - The BestSean Bofill-GallardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kimba Spring Manual PDFDocument16 paginiKimba Spring Manual PDFpaulina_810Încă nu există evaluări

- Vitalsox Outdoor CatalogDocument16 paginiVitalsox Outdoor CatalogTravelsox- Caresox- Vitalsox- Worksox- SoxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 1 Lesson 2 Tongue TwistersDocument14 paginiWeek 1 Lesson 2 Tongue Twistersapi-246058425Încă nu există evaluări

- SVA HandoutDocument2 paginiSVA HandoutWemart SalandronÎncă nu există evaluări

- BGMEA - Associate - Member - List - 2023 - 3Document79 paginiBGMEA - Associate - Member - List - 2023 - 3bibahabondhonitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rapada Aquino Chapter 1 RevisedDocument6 paginiRapada Aquino Chapter 1 RevisedHomecoming ProtmannianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Polis Akademiyası 1-Ci Kurs 4-Cü Taqım Kursantı İskəndərov Fuadın İngilis Dilindən SƏRBƏST Işi Lesson:6 My Brother's FlatDocument13 paginiPolis Akademiyası 1-Ci Kurs 4-Cü Taqım Kursantı İskəndərov Fuadın İngilis Dilindən SƏRBƏST Işi Lesson:6 My Brother's FlatleylaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Meeting 5: Talking About: Travel, Vacations and PlansDocument11 paginiMeeting 5: Talking About: Travel, Vacations and PlansAmyunJun CottonÎncă nu există evaluări

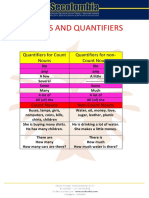

- Nouns and QuantifiersDocument3 paginiNouns and QuantifiersAndres PerezÎncă nu există evaluări

- LESSON PLAN IN ENGLISH 3and4 - Q2W1Document23 paginiLESSON PLAN IN ENGLISH 3and4 - Q2W1Ceejay MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Listening For Academic Purposes: Toefl - Listening Complete TestDocument8 paginiListening For Academic Purposes: Toefl - Listening Complete TestArina UlfahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mix Present Simple, Present Continuous.Document4 paginiMix Present Simple, Present Continuous.AlwaysAna MiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nwn2 CraftingDocument71 paginiNwn2 Craftingsh1tty_cookÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Production and Supply Chain of Malian BogolanDocument5 paginiThe Production and Supply Chain of Malian Bogolanealawton4Încă nu există evaluări

- Multi-Needle (Cylinder-Bed) : SpecificationsDocument1 paginăMulti-Needle (Cylinder-Bed) : SpecificationsJun Loi BongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alpha2016 SSDocument53 paginiAlpha2016 SSmegyo4682Încă nu există evaluări

- Lista Arome BunaaaaaaaaaaaDocument3 paginiLista Arome BunaaaaaaaaaaaAlin RazvanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Give It To The ManDocument14 paginiGive It To The Manmgpotter.19Încă nu există evaluări

- 【F】 Quiet Luxury Watches JLC, Chopard, Blancpain, And MoreDocument1 pagină【F】 Quiet Luxury Watches JLC, Chopard, Blancpain, And MoreCreeperhikeÎncă nu există evaluări