Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Calhoun - An Apology For Moral Shame

Încărcat de

Rocío CázaresDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Calhoun - An Apology For Moral Shame

Încărcat de

Rocío CázaresDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Journal of Political Philosophy: Volume 12, Number 2, 2004, pp.

127146

An Apology for Moral Shame*

Cheshire Calhoun

Philosophy, Colby College

N DAILY life, we often use shaming criticisms like Shame on you, I expected more from you, or What kind of a friend are you? to impress our moral expectations on others. We expect people to feel ashamed of being petty, of snooping through others mail, of refusing to do a simple favor, or of pretending not to see people who want a moment of their time. We think that some people who are not ashamed should belike the many young men in my classes who shamelessly confess to misdirecting lost people. In short, in our everyday exchanges with other people, we act as though moral shame over bad behavior is simply to be expected of any mature moral agent. Occasionally, philosophers have also thought that shame is important to the life of a moral agent. In a 1939 article published in Ethics, Virgil Aldrich suggested that feelings of shame provide us with much more reliable and concrete moral guidance than any appeal to principle or consequences does. He urged the adoption of a new Golden Rule: Never do anything which you would feel ashamed to do and always do what you would feel ashamed not to do.1 Generally, however, philosophers, have not shared this positive outlook on shames moral importance. More often, one nds analyses of shame that displace it from any signicant role in morality. Shame, it is said, is not a response to moral wrongdoing, but something we feel when we have had a shock to our selfesteem, or when we discover our shortcomings in relation to our Ego Ideal, or when our failure to be or act as bets our station in life is publicly exposed.2 Or, if shame is a moral emotion, it is a more primitive and less useful moral emotion than guilt, one that both cultures and individuals would be better off moving

*I am grateful to the National Endowment for the Humanities for their nancial support. Special thanks to Dianne Romain, Jennifer Vest and Gary Watson for thoughtful suggestions. Thanks also to the Northern California SWIP, faculty and graduate students of University of California-Davis, University of California-Riverside, and University of Louisville for helpful comments. 1 Virgil C. Aldrich, An Ethics of Shame, Ethics, 50 (1939), 5777. 2 John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971); John Deigh, Shame and Self-Esteem: A Critique, Ethics, 93 (1983), 22545; Gabriele Taylor, Pride, Shame, and Guilt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985); Gerhart Piers and Milton B. Singer, Shame and Guilt: A Psychoanalytic and a Cultural Study (Springeld, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher, 1953); Self-Conscious Emotions: The Psychology of Shame, Guilt, Embarrassment and Pride, ed. June Price Tangney and Kurt W. Fischer (New York: Guilford Press, 1995). Blackwell Publishing, 2004, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

128

CHESHIRE CALHOUN

past.3 That is because shame seems less directed at the wrong done than at how we appear, or how others will receive us, or what good or bad opinion we are entitled to have of ourselves. Thus what fuels philosophers suspicions about the value of feeling ashamed is the way shame seems to shift attention away from what morality requires to what other people require us to do or be like. In shame, we see ourselves through others eyes and measure ourselves by standards that we may not share. We take seriously the prospect of being subjected to ridicule, demeaning treatment, or social ostracism for falling short of others moral standards. And we fear being exposed as the less worthy beings they might take us to be. The problem with shame, then, is that vulnerability to being shamed appears to signal the agents failure to sustain her own autonomous judgment about what morality requires. Given this, it might well seem morally preferable for agents to be, or to strive to be, insensitive to the shaming gaze of others and attentive only to the demands of their own practical reason. This might seem particularly good moral advice for members of socially subordinated groups. The sorts of shaming criticisms to which racial minorities, the poor, women, Jews, lesbians and gay men and so on are subjected often repeat demeaning cultural stereotypes of group members moral character (for example, as lazy, or untrustworthy, or mendacious). Shaming criticisms may also repetitively attribute diminished capacity for moral agency, thereby implicitly rationalizing cultural practices that give subordinate groups lesser moral consideration. Women of all races, for example, are more likely than white men to be criticized for irrationality, lack of self-control, and inadequate attention to principle. They are thus given cause to feel ashamed of their agency. Shaming criticisms may also be leveled against anyone (whether subordinated or privileged) who does not conform to sexist, racist, etc. norms of behavior or who protests the demeaning or unequal treatment of social subordinates. In short, in societies structured by relations of domination and subordination, shame is an especially worrisome moral emotion. Subordinated people who suffer shame before bigoted criticisms seem to have failed to achieve (or failed to be able to sustain) a sufciently critical moral perspective. They are thus not well positioned to challenge the gender, racial, sexual, and religious politics that erode their life prospects. The subordinate would be better off ignoring others shaming criticisms and shamelessly pursuing more egalitarian ideals.

3 June Price Tangney argues that shame is morally counterproductive, because shame often motivates hostile aggression toward shamers, and shamed people typically fail to empathize with the victims of their wrongdoing; June Price Tangney, Shame & Guilt in Interpersonal Relationships, Self-Conscious Emotions. John Kekes claims that shame rivets the agents attention on the defectiveness of the self, undermining self-condence and paralyzing action; John Kekes, Shame and Moral Progress, Ethical Theory: Character & Virtue, Midwestern Studies in Philosophy, vol. 13, ed. Peter A. French, Theodore E. Uehling Jr., Howard K. Wettstein (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1988).

AN APOLOGY FOR MORAL SHAME

129

In what follows, I plan to side with our everyday assumptions about the importance of feeling morally ashamed. I think that shame over moral failings is essential to a mature ethical agents psychology. More controversially, I think that vulnerability to feeling ashamed before those with whom one shares a moral practice, even when one disagrees with their moral criticisms, is often a mark of moral maturity. It need not spring from any failure in autonomous judgment. Thus, I think it is possible to understand the pervasiveness of shame among socially subordinated groups without either attributing to them internalized contempt of their own social group or attributing a failure to maintain their own critical perspective in the face of others shaming contempt. I. SHAME AND AUTONOMY: TWO STRATEGIES OF RECONCILIATION Given the worry that shame signals a heteronomous and excessive concern with others opinions, any good defense of moral shame will have to show that, despite appearances, moral shame is in fact compatible with autonomous moral judgment. The most obvious strategy is to argue that morally mature persons only feel shame over their failure to live up to their own, autonomously set standards. There are two fairly different ways of conducting this game plan. One is represented by such authors as Anthony OHear, John Kekes and Virgil C. Aldrich.4 I will call this the shame of the moral pioneer strategy. This strategy reconciles shame with autonomy by claiming that mature agents only feel shame in their own eyes, and only for falling short of their own, autonomously set standards. The second strategy is represented by Bernard Williams in Shame and Necessity. I will call this the shame of the discriminating social actor strategy. This strategy reconciles shame with autonomy by claiming that mature agents only feel shame in the eyes of others whose ethical reactions they respect. Neither strategy, I will argue, satisfactorily reconciles shame and autonomy. Both make shame suitable for an autonomous agent only by reducing the other before whom we feel shame to a mirror of ourselves. Both drop from view the fundamentally social nature of shame. I will then suggest, in Section II, a third strategy that I think works better. In pursuing it, I will be stressing the fact that morality is something practiced with others in a social world. Taking others seriously as co-participants in a moral practice means giving their opinions weightand thus the power to shame. A. THE SHAME

OF THE

MORAL PIONEER STRATEGY

Let us start, then, with the rst strategy. Those who adopt the shame of the moral pioneer strategy claim that shame does not require a real or imagined

4 Anthony OHear, Guilt and Shame as Moral Concepts, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 77 (19761977), 7386; John Kekes, Shame and Moral Progress; Virgil C. Aldrich, An Ethics of Shame.

130

CHESHIRE CALHOUN

audience before whom one might feel shame. It is not the eyes of others that matter. What matters for the experience of shame is that there be some moral standards that one cares about living up to. And the mature ethical agent will only care about standards that she autonomously sets for herself. Those standards could, of course, be those of a conventional social morality so long as the agent adopts them for her own. Those standards could also, in theory, be entirely idiosyncratic ones that no one else shares. They could, for example, be the standards of a lone moral pioneer whose moral vision outstrips that of her social world. Such a lone pioneer would be shameless before her less enlightened social peers and ashamed only before her private moral court. In a sense, however, all shame on this view is simply shame before oneself. That is because, on this view, an agent will experience anothers moral criticisms as shaming only if he already endorses the others standards and specic criticism.5 This way of thinking about the mature ethical agents shame ts nicely with a standard way of contrasting moral immaturity with moral maturity. Immature moral agents submit to external moral standards. Children, for example, begin by uncritically submitting to parental prohibitions and then later submit to what their larger social world prohibits and requires. As individuals morally mature, their submission to a particular set of moral requirements becomes increasingly independent of the consideration that others will approve obedience and disapprove disobedience. Instead, the standards that have authority are increasingly based on reasons that might be shared by rational beings (but that may not in fact be shared by those in ones social world). Full moral maturity arrives with the development of an autonomous practical reason that enables the individual to arrive at her or his own moral standards and specic moral judgments. Those reectively endorsed standards give the agent critical purchase on conventional morality. Shame, on the view just described, traces a similar developmental path. Childrens earliest experience of moral shame stems from being observed violating parental prohibitions, and later, conventional moral prohibitions. In both cases, the immature are shamed simply by others critical gaze. Moral maturity arrives when agents learn to spurn public opinion and think for themselves.6 Mature agents are then only shamed when they fall short of their own standards. Such accounts of moral shame appear to solve the original problem. Moral shame does not necessarily signal heteronomy. The mature ethical agent feels shame before her own autonomous evaluative gaze. Unfortunately the price of reconciling moral shame and autonomy this way is the loss of a plausible depiction of shame.

OHear, Guilt and Shame as Moral Concepts, p. 77. John Kekes draws a similar contrast between what he calls honor shameshame at violating public, conventional standardsand worth shamethe shame felt by self-directive people who spurn public opinion in the name of private standards (Shame and Moral Progress, p. 293).

6 5

AN APOLOGY FOR MORAL SHAME

131

To see this, imagine a moral pioneersomeone who has achieved a level of moral knowledge that her less enlightened social peers have not. If she transgresses her moral standards, she will be treating her social peers badly by her lights. They, however, will not realize this; and no one in her social world will think badly of her. Under these circumstances, a moral pioneer could surely feel guilty about mistreating unwitting peers. That they fail, out of ignorance, to protest is no safeguard against guilt. (Indeed, her guilt at mistreating her peers might then be compounded with guilt at getting away with it.) Proponents of the shame of the moral pioneer account add that this moral pioneer should also feel ashamed of herself. On their view, what others might think of her is utterly irrelevant to mature shame experiences. So she should feel ashamed even though none of her peers do, or could, morally criticize her. But this does not seem right.7 Like other forms of shame, moral shame seems intrinsically tied to the thought of social others actual or imagined contempt.8 Moral shortcomings must rst be exposed to public view before they can be the source of shame; or at the very least, the contempt that others would show us were our shortcoming exposed must be clearly imaginable. The primary fears attached to shame are fears of being ridiculed, made the subject of gossip, subjected to demeaning treatment, and of being ostracized or abandoned.9 Thus, shame is strongly connected with the desire to conceal failings from others view, with fear of exposure, and with anxiety about how it will be for ones life with others if one acts shamefully.10 The rst strategy for reconciling shame with autonomy cannot explain these connections. On the contrary, it severs the connection between shame and concern for ones standing in a social world. It does so because it mistakenly takes the object of shame to be what the agent alone believes is a moral failing. The real objects of shame, however, are failures to meet moral standards that are also held by other people. Shaming moral failures are paradigmatically ones that might, if exposed, reduce ones social standing in some actual group and might degrade the quality of ones social interactions.

7 We do sometimes feel ashamed even though witnesses of the act do not think it shameful. A parent might feel ashamed of slapping his child even though he is among parents who believe in corporal punishment. A diner at the Cattlemens Association dinner might feel ashamed of eating the veal. Shame in these cases is possible, however, because not everyone in ones social world believes that corporally punishing children and eating veal are permissible. Some really would nd slapping a child and eating veal contemptible. The parents and diners shame is shame at failing to live up to the standards of these other people. The case of the ashamed moral pioneer is different. We are supposing that none of her social peers recognize the wrong she has done. Indeed, they are unable to recognize it. 8 John Deigh makes an especially persuasive case that a satisfactory characterization [of shame] must include in a central role ones concern for the opinions of others (Shame and Self-Esteem, p. 238). The others, whose opinion one cares about, however need not be living. One can feel ashamed imagining what ones beloved grandmother would have thought were she still living. 9 Piers and Singer, Shame & Guilt. 10 Bernard Williams, Shame and Necessity (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1993), p. 102.

132

CHESHIRE CALHOUN

Proponents of the shame of the moral pioneer strategy could try to defend the plausibility of their picture of shame in the following way. The moral pioneer, they might argue, imagines a social world where her enlightened standards are publicly shared. She thus imagines people before whom she could feel shame and among whom she would lose standing were her failings exposed. In this way, shame is reconciled with autonomy: The standards she is ashamed of failing are hers. And autonomy is reconciled with concern about how one appears to others: People in this imagined social group judge her by the same standards. The reconciliation, however, is more apparent than real. The only opinions of others (real or imagined) that the autonomous person will be shamed by are ones that she shares. When the moral pioneer says, I can imagine social peers whose criticisms would shame me, she must be prepared to add, if she is in fact an autonomous judge, But I would not feel shame if I did not share their view. That is, in order for the mature agents shame to remain rmly tied to her own autonomously chosen moral standards, the others before whom she can imagine feeling shame cannot be thought of as persons with their own minds that they might make up differently. They cannot be imagined as full others. Instead, they must be imagined to be people who reach the same moral conclusions she does because their minds mirror her own. They are simply stand-ins for her own reactions to herself.11 It is only because others mirror the agent that feeling shamed by their moral criticisms does not threaten her autonomy. In sum, the shame of the moral pioneer account seeks to make shame and autonomy compatible in order to explain why moral shame would be part of the mature ethical agents emotional repertoire. But the particular strategyof claiming that mature agents are only shamed by criticisms that mirror their own self-criticismsuggests that shame is no more tied to the social than is guilt. Mature shame, like mature guilt, centers on how one appears in ones own eyes. Concern about how one appears in others eyes, fear of having discrediting facts socially exposed, anxiety about others contempt and about having ones social relations impaired may accompany shame. But on this view they are not central to and distinctive of shame experiences (or at any rate, to mature shame experiences). B. THE SHAME

OF THE

DISCRIMINATING SOCIAL ACTOR STRATEGY

In light of the implausibility of detaching shame from an awareness of how we appear to others, Bernard Williams pursues a different strategy for countering the objection that shame signals excessive heteronomy. Central to this strategy is insistence that shame is always shame in the eyes of real social others. Williams suggests that it seems difcult to place this social shame in the mature ethical agents psychology because we have inherited from Kant a tendency to oppose

11

Williams, Shame and Necessity, p. 84.

AN APOLOGY FOR MORAL SHAME

133

capital-M morality to conventional standards, individual judgment to social judgment, and autonomy to heteronomy. Thus we end up thinking that there are only two options: Either we are autonomous, set moral standards for ourselves, are unconcerned about the opinions of others, and are invulnerable to shaming criticisms, or we fall into heteronomy, uncritically take on whatever moral standard our social peers use, care deeply about how we appear to others, and are vulnerable to every shaming criticism.12 There is, however, a third option. We can reconcile the essentially social nature of shame with autonomy if we keep in mind that at any point in time there typically are many ethical standards endorsed within ones social world. Immature or poorly developed agents do not discriminate among these standards and thus may be shamed by virtually every moral criticism levied at them. But ethically well-developed agents care only about the opinions of some social others. They choose whose standards to respect and thus whose eyes will have the power to shame. If they are to be worthy of respect, those standards will largely mirror the agents own. Thus criticisms that the agent nds outlandish or irrational because they fail in important ways to mirror her own evaluative standards and cannons of reasoning will not inspire shame.13 It does not, however, follow that the criticisms that do inspire shame must mirror the agents own self-criticism. As I interpret Williams, he leaves open the possibility that respected others can shame us with their criticisms even when we disagree with their evaluation of us. Mature moral agents care about how they appear in the eyes of respected others. They care how they appear because they have a general respect for the others evaluative commitments, skill at moral reasoning, and perceptiveness. That general respect grounds the power to shame, and thus people may be shamed by particular criticisms that fail to mirror their own selfcriticism. In this way, Williams allows for the evaluative gaze of others, fears of exposure, anxiety about others contemptthat is, the social dimensions of shameto play a central role in his account of shame independently of our own self-assessments. At the same time, mature shame experiences are ultimately tethered to the agents own evaluative standards, since she must choose whose evaluative gaze merits her respect. So while it is true that shame is always shame in the eyes of real social others who will interact with me differently if my moral failing is exposed, vulnerability to shame does not entail an abdication of individual judgment. On the contrary, individual judgment is critical to ethically mature shame. What distinguishes the discriminating social actor strategy from the moral pioneer strategy is, rst, that the eyes of (some, respected) others have the power to shame independently of their exactly mirroring the agents eyes. Second, it matters that the others before whom I might be shamed are real social others,

Ibid. Both Jeffrey King and Jennifer Vest proposed this way of thinking about who has the power to shame.

13 12

134

CHESHIRE CALHOUN

not merely imagined others. Williams refuses to disconnect shame from the eyes and standards of people in our lived social world. In theory, a reective agent might decide that none of the standards instantiated in her social world deserves respect. If no eyes merit her respect, then no gaze within her social world will have the power to shame her. He thus leaves open the possibility that the autonomous choice of standards might result in an inability to feel shame. But Williams argues that agents have good reason not to divorce themselves altogether from social standards of morality, and thus not to become shameless. That reason is provided by the indeterminacy of moral truth.

But if we now think, plausibly enough, that the power of reason is not enough by itself to distinguish good and bad; if we think yet more plausibly, that even if it is, it is not very good at making its effects indubitably obvious, then we should hope that there is some limit to these peoples autonomy, that there is an internalized other in them that carries some genuine social weight. Without it, the convictions of autonomous self-legislation may become hard to distinguish from an insensate degree of moral egoism.14

Thus, because moral opinions do not come clearly labeled correct or incorrect, an agent who comes to moral conclusions that diverge substantially from any endorsed within her social world has no way of telling for sure whether she is a moral revolutionary whose views advance the social stock of moral knowledge or a deluded crank. Agents thus have good reason to give signicant weight to the best among the available standards already ourishing within their social world. In this way, vulnerability to shame ends up securely anchored in the mature ethical agents psychology. I think Williams is right to insist that shame is a social emotion Neither our own solitary gaze nor the gaze of purely fantasized others can trigger shame. But this second strategy for reconciling shame and autonomy is ultimately vulnerable to much the same criticism that the rst strategy was: The distinctively social character of shame and the power of others eyes to shame is not adequately accounted for. On this second strategy, the mature ethical agent reects on others standards and decides whose she respects. But in order to evaluate others standards, she must already have standards of her own. This means that others criticisms have the power to shame only because they invoke standards that she already largely endorses. Notice, others power to shame turns entirely on the question of what their standards are. Are they ones the agent endorses? Thus the standard by which the agent is judged is what explains whether she will or will not be vulnerable to being shamed. That she is exposed to another who views her with contempt and will now interact with her differently plays no independent role. It is true that Williams aims to give an account of shame where others opinions have social weight; he also seems to allow for the possibility that others

14

Williams, Shame and Necessity, p. 100, emphasis mine.

AN APOLOGY FOR MORAL SHAME

135

particular criticisms of us will have this social weight, and hence the power to shame, even when we reject those criticisms. But in the end, what it means for anothers opinion to have a social weight independent of ones endorsement remains unexplained. On the contrary, since this view, like the rst strategy, traces the power to shame to the shamers mirroring to a large extent the agents own evaluative perspective, it is not clear why moral criticisms with which one disagrees would have any power to shame at all. That I share anothers standards may explain why, in general, I respect her and care how I appear in her eyes. But it does not explain why I would respect her and care about how I appear in her eyes when she misjudges me. Since on this view, as on the rst strategy, the power to shame ultimately comes from my endorsement of the others evaluative outlook and not from the fact that an other appraises me, it is hard to see why particular moral criticisms shame an agent who does not endorse them. In short, any strategy that reconciles shame with autonomy by rooting the power to shame in the agents endorsement of the shamers evaluations will have trouble capturing shames distinctively social character. If shames more social nature than guilt is to be explained, then we need to trace the power to shame to a more social source. What could it mean for an opinion to have social weight independently of the agents endorsement of the shamers standards and particular criticisms? And how is sensitivity to the social weight of others opinions compatible with being an autonomous moral judge? Before turning to these questions, it is worth looking at one nal problematic feature of the two strategies for reconciling shame and autonomy considered so far. C. SHAME BEFORE

THE

OTHERS UNMIRRORED GAZE

Grounding the mature agents shame in her own self-criticism not only fails to explain the social character of shame; it forces us to discount as irrational or immature common shame experiences. On the discriminating social actor view, and even more so on the moral pioneer view, a man who sees nothing wrong with his purchasing sexual services yet suffers shame when his name appears in the newspapers list of Johns is not experiencing the predictable shame of a mature, well-formed ethical agent.15 A mature, well-formed ethical agent would only feel shamed by moral criticisms that mirror his own, or that at least invoke ethical standards he respects. More worrisome, we must discount as irrational or immature much of the shame suffered by socially disesteemed populationsracial minorities, women, the poor, lesbians and gay men. As Sandra Bartky observes, shame, for the subordinated, is the pervasive affective

15 Some advocate shaming penalties as an alternative to prison time for some crimes; see for example, Dan M. Kahan, What Do Alternative Sanctions Mean? The University of Chicago Law Review, 63 (1996), 591653. This seems to presuppose that it is natural for mature moral agents to be vulnerable to shaming criticisms even when they see nothing wrong with what they have done.

136

CHESHIRE CALHOUN

taste of a life in which being subjected to shaming treatment is a routine part of social interaction.16 Some of the shaming criticism is specically moral, as when black men are routinely suspected of being shoplifters or muggers, or when the poor are assumed to have brought poverty on themselves through their own laziness or lack of self-control; some is not, as when female and black students are presumed to be less educable. Pervasive shame often coexists, however, with a denial that there is anything to be ashamed of. The women students that Bartky so poignantly describes are a case in point. At a discursive level, they believe their work is meritorious. They would deny that they are unintelligent or unable to compete academically. They would not respect the attitudes of teachers who ridicule or demean them in class. However, having been regularly demeaned in the classroom throughout their educational lives, they have come to be ashamed of their work, ashamed to express their ideas, and fearful of incurring punitive or demeaning treatment in the classroom. Shame moves them to apologize for the quality of their work, to express themselves without condence, to bow their heads and hunch their shoulders. The two strategies we have considered must both conclude that these women are not experiencing the predictable shame of a mature, well-formed ethical agent. On both views, shaming classroom experiences would not faze a rational, mature person, convinced of her own academic talent. She would ignore or scoff at her teachers contempt. The fact that these women feel shamed while claiming to believe in their academic talent shows that there is something awry with them. Perhaps they do not know their own minds; deep down they really do believe they are unintelligent and unable to compete. Or perhaps they lack strength of mind; they succumb to others opinions and abandon their own view of themselves. Or perhaps the problem is what Bartky suggests it is. They hold inconsistent views of themselvesone at the discursive level of belief, one at a nondiscursive level of feeling.17 Whatever the diagnosis, the conclusion is the same. No rational, mature person who rmly rejects her subordinate social status would feel shame in the face of sexist, racist, homophobic or classist expressions of contempt.18 The two views we have considered so far thus encourage us, at best, to seek out psychological explanations for these irrational shame responses;

16 Sandra Lee Bartky, Shame and Gender, in her Femininity and Domination: Studies in the Phenomenology of Oppression (New York: Routledge, 1990), p. 96. 17 Ullaliina Lehtinen, How Does One Know What Shame Is? Epistemology, Emotions, and Forms of Life in Juxtaposition, Hypatia, 13 (1998), 5677, proposes a similar analysis of the shame of the oppressed. Following Bartky, she argues that women are less likely than men to be able to autonomously defy shamers judgments because women have internalized a low self-evaluation. Thus for women and other subordinated persons, experiences of shame function as conrmations of what the agent knew all alongthat she or he was a person of lesser worth (p. 62). Notice how the pervasive shame experienced by members of subordinated groups is explained by attributing low self-esteem to them. 18 Someone who insists that rational, mature people would not feel shamed by criticisms they reject might nevertheless think that they could experience some other unpleasant feeling such as discomfort at the awkwardness of having to interact with openly sexist or racist people. One need not agree with a would-be shamers contemptuous views to be made uncomfortable by them.

AN APOLOGY FOR MORAL SHAME

137

and at worst, to chastise the subordinated for feeling ashamed and to exhort them to buck up, think for themselves, be more thick-skinned, and spurn public opinion. That is, they encourage us to nd fault with ashamed people.19 This strikes me as both uncharitable and the wrong conclusion. It may be true that Bartkys women students feel shame because they fail to sustain their own positive self-evaluation. Their shame and apologetic, self-effacing behavior are consistent with a low self-evaluation. Feeling ashamed, however, does not entail that they agree with their shamers contempt. That people who wholeheartedly condemn sexist or racist insults are still vulnerable to feeling shamed by those insults, and that this is a perfectly natural response for a mature, well-formed agent to have, is made painfully clear by Adrian Piper in her narratives of being shamed in academia.20 She gives us every reason to believe (as Bartkys students do not) that she is perfectly capable of sustaining her condence in her own worth no matter how insultingly she is treated. By her own account, Piper was raised by parents who tried to provide her with an invincible armor of selfworth with which to ght [racism].21 As a result her instinctive reaction to racist insults is the disbelief, outrage, sense of injustice, and impulse to ght back actively that white males often exhibit at unexpected affronts to their dignity.22 Pipers rm belief in her own worth and in the unacceptability of racism does not, however, protect her against shame. Here is one of her stories: Refusing to pass as white, although she could, Piper identies herself on graduate school applications as black. When she shows up at the reception for new graduate students she is approached by a professor, one of her intellectual heroes, who remarks with a triumphant smirk, Miss Piper, youre about as black as I am.23 This is one of a series of occasions on which Piper feels what she calls groundless shame in response to those who accuse her of passing for black or passing for white. Her shame is groundless because she does not share her shamers particular moral criticism of her that she is manipulative or deceitful. The moral pioneer strategy would thus have to conclude that Pipers shame reaction does not bet a mature moral agent. One might also imagine that she also does not share with him more general normative views about what the moral point of afrmative action policies is and who is permitted to present themselves as an afrmative action candidate; about what integrity requires from persons who could pass as the bearer of a less discrediting identity; about what general sorts of actions a commitment to resisting racial oppression requires; and about the proper application of evaluative concepts like honesty, integrity, manipulativeness and racism. Of course, Piper and the professor share some

The fault here need not be culpable. Adrian Piper, Passing for White, Passing for Black, Passing and the Fictions of Identity, ed. Elaine Ginsberg (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 1996). Thanks to Gary Watson for drawing my attention to this piece. 21 Ibid, p. 239. 22 Ibid, p. 260. 23 Ibid, p. 234.

20 19

138

CHESHIRE CALHOUN

evaluative views in commonfor example, the wrongness of deceit and manipulation, understood very abstractly. But absent more robust commonalities, especially ones connected to Pipers antiracist commitments, agreement that deceit and manipulation, abstractly described, are wrong looks insufcient to ground a respect for the professors standards that would make her care how she appears in his eyes. Thus the discriminating social actor view must also conclude that Pipers shame reaction does not bet a mature moral agent. Yet shame, not just social discomfort, seems the reasonable response to being treated with contempt by people whose evaluations partially dene who these women are within a shared educational practice. Rather than signaling a failure to sustain their own positive views of themselves, their shame instead signals their capacity to take seriously fellow participants in their social world. I turn now to the question of what it might mean to take others seriouslyto give their opinions weight. II. THE WEIGHT OF OTHERS JUDGMENT One might be skeptical that Bartkys and Pipers examples are really examples of mature shame experiences. These shame experiences might be psychologically understandable. But we expect mature agents to be autonomous, that is, to rely on their own judgment. It is thus tempting to say to Bartkys students and to Piper, You should not be shamed by the wrongheaded opinions of others. After all, in your own view, you have nothing to be ashamed of. Spelling out this skepticism more formally, we have the following familiar and compelling argument: 1. Moral shame is made possible by the fact that we take others appraisals of our moral shortcomings seriously; we give them weight. 2. The mature ethical agent is an autonomous self-legislator; this means that mature agents submit only to the demands of their own practical reason. 3. Mature ethical agents thus have reason to take others appraisals of their shortcomings seriouslyto give them weightonly if those appraisals mirror the agents reasoning. 4. Thus, mature ethical agents will only feel shamed by the appraisals of others when those appraisals mirror the agents own reasoning about her shortcomings. The shame of the moral pioneer account draws quite clearly on this line of reasoning. The shame of the discriminating social actor account draws on a kindred line of reasoning, since it invokes the importance of agents determining for themselves whose practical reasoning they respect enough to accept even when it might diverge from their own.

AN APOLOGY FOR MORAL SHAME

139

What could be wrong with the argument? Premise one simply afrms a principal feature of shame, namely, that it is fundamentally a social emotion. Premise two afrms an equally uncontroversial connection between moral maturity and autonomy. That mature agents submit only to the demands of their own practical reason does not mean adopting a policy of dismissing others views whenever they disagree with ones own. It does mean that ultimately agents must make up their own minds; and doing so may mean reaching the sincere conviction that others are wrong and one is going to stick by ones guns. Both Bartkys students, and even more obviously Piper, are autonomous self-legislators in this sense. Exposed to repeated critical messages they make up their own minds not to believe those messages. This leaves premise three: Mature ethical agents have reason to take others appraisals of their shortcomings seriouslyto give them weightonly if those appraisals mirror the agents reasoning. At rst glance, this premise seems to follow from the thought that mature agents are self-legislators who make up their own minds. After all, if I have made up my mind that others criticisms are misguided, how could I give those criticisms weight? Would not giving them enough weight to shame me amount to giving in to others view of me? I do not think so. That a person can only be shamed by a view of herself that she accepts as true, at some level, is not supported by everyday experience. It is instead a lacuna in our moral theories that makes it seem that in order for an opinion to have shaming weight, we must at some level accept it as true. Moral theories are typically slanted toward moral epistemology, and this induces us to think that weight must be an epistemic notion. It must have something to do with the weight of reasons, a weighty argument, or the compelling force of truth. The assumption that weight is an epistemic notion then drives us toward the idea that for others opinions to have weight is for those opinions to have weight in our reasoning process. But if they weigh in our reasoning process, we must have accepted their truth. Moral agents, however, are not just knowers. They are also participants in various social practices of morality with other people. What I want to suggest is that the weight central to shame is not an epistemic notion. It is instead the weight that other people have for us when we acknowledge them as fellow social participants. That an others view of us has weight in this latter sense is compatible with denying its truth. Moral criticism that shames has what I will call practical weight. Moral criticism has practical weight when we see it as issuing from those who are to be taken seriously because they are co-participants with us in some shared social practice of morality. Co-participants stand in a different relation to us than do agents in general. Agents in general are responsible beings, open to reason, and capable of exhibiting good will. We take their moral interpretations seriously by listening to what they have to say, engaging in moral dialogue, taking care not to give

140

CHESHIRE CALHOUN

offense needlessly, and so on. Co-participants are more than this, and we take their moral interpretations seriously in a thicker, more substantive way.24 Coparticipants are part of a moral we that shares a social practice of morality.25 That social practice generates shared understandings about exactly what is obligatory and what is supererogatory as well as shared understandings about how to interpret when basic moral obligations, like the duty of truth-telling, have been fullled. Physicians, for example, generate shared understandings about the required level of disclosure to patients and about the moral status of hastening death. Co-participants are thus able to engage in a shared enterprise of evaluating each others behavior and character, determining who has lived up to and who has fallen short of shared moral ideals, and calling each other to moral account for transgressions. A social practice of morality comes about because there is something else that we want to do togetherwork in a profession, engage in religious worship, play sports, live together in a neighborhood, have a marriage. These various activities are sites of particular moral problems that produce the need to generate shared moral norms. The practice of education, for example, produces a need for norms governing studentteacher relations, including sexual relations. The practice of medicine generates a need for norms governing the response to terminal illness. Those moral norms then get hammered out among people who already share a social world. In everyday life, we move among a plurality of moral practices. Each has its own shared understandings about how we do thingsones family of origin, the family one creates as an adult, ones workplace, ones profession, ones neighborhood, ones political association, ones religion, and so on. All of these groups engage in the business of negotiating and articulating moral norms. This is how we do things in our family: we spend major holidays together; this is how we do things in our profession: we do not have sexual relations with students (or clients or patients); this is how we do things in our religion: we do not divorce; this is how we do things in a participatory democracy: we engage in civil dialogue. Shaming criticisms work by impressing upon the person that she has disappointed not just one individuals expectations but what some we expected of her. In effect they say, You claim to be one of us, but just look how

24 Taking agents seriously by listening to what they have to say, engaging in moral dialogue, and taking care not to give offense is compatible with denying that others have the standing to criticize us. A pro-choice woman might take seriously a religious conservatives condemnation of abortion by civilly listening and responding to that view. In the thicker more substantive sense, the prochoice woman does not take seriously the religious conservatives moral appraisal. Because their views on abortion derive from different social practices of morality, the pro-choice woman has no reason to acknowledge the religious conservatives standing to criticize her reproductive choices and call her to account. The accusation You murdered your unborn child does not dene who she is for others within the social worlds she claims as her own. As a result, it lacks the power to shame. 25 The following discussion owes a good deal to Margaret Walkers Moral Understandings: A Feminist Study in Ethics (New York: Routledge, 1998).

AN APOLOGY FOR MORAL SHAME

141

youre behaving! The power to shame is a function of our sharing a moral practice with the shamer and recognizing that the shamers opinion expresses a representative viewpoint within that practice. The shamers opinion tells us who we are for any number of co-participants within a social practice of morality that we take ourselves to be a part of. Shaming criticisms have, in this sense, practical weight. An extended example may help clarify this notion of practical weight. Imagine an agent who nds herself seen critically by her faculty colleague. Perhaps he lets her know that he thinks she is manipulative of colleagues or insensitive to student needs. Suppose, now, that on reection she rejects this assessment. He has misinterpreted the facts. Or perhaps his conception of these vices is awed. Given the opportunity, she may try to remove the criticism by trying to change his mind. She argues with him. She lays out the facts. She invites him to rethink what he imagines manipulativeness or insensitivity to be. But this may not be effective. He disagrees. Perhaps he thinks her arguments conrm his very point (look how she tries to manipulate him in this argument!). She is now left with the fact that she is for him this morally awed person. Faced with his unchangeable critical gaze, she has two options. First, she could shift out of the participant attitude, refusing to take him seriously. He is paranoid, she might tell herself, and thus is disabled from being a competent judge. Or he is new to this profession or this school, and thus is not yet a competent judge. In short, he is only someone to be humored or resignedly suffered, or avoided, or written off. His criticism is deactivatedit now lacks practical weightbecause he is not someone to be taken seriously as a competent participant in this social practice of morality. Dismissed as pathological or an outsider, his critical gaze cannot represent a general viewpoint that any number of colleagues might take. Thus what he thinks of her cannot dene one of the (shameful) ways she is for others in her social world. His gaze lacks the power to shame because it is nonrepresentative. Alternatively, she could sustain the participant attitude even though she thinks he is wrong. She continues to take him seriously as a person who has the standing to criticize her. She does not write him off by attributing his misjudgment to some aw or inexperience that undermines his standing as a co-participant in this moral practice. Instead his is the sort of misjudgment co-participants just do make. One of the permanent hazards of engaging in a social practice of morality is that one ends up being criticized and sometimes ridiculed by people whose moral appraisals one does not agree with. The hazard is a serious one because their appraisals may be representative ones. Who they take us to be represents what any number of fellow co-participants would take us to be. Their eyes dene one of the many public identities that we have for others within our shared social practice of morality. Some of those public identities are shameful ones. In sum, I am proposing that vulnerability to shame has more to do with our sharing a moral practice with others than it does with accepting anothers

142

CHESHIRE CALHOUN

criticism. Of course, when we share a moral practice with others we typically will share certain basic moral values, principles, and styles of reasoning with them. Thus there will usually be something in our shamers evaluative thinking to which we attach epistemic weight. Bartkys shamed students, for example, surely shared their teachers standards of academic excellence. We need to be careful, however, not to infer that others power to shame derives entirely from the fact that we endorse their evaluative framework. Sharing basic values and reasoning styles with other people does not explain why particular criticisms are felt to be shaming, since we may reject particular criticisms while endorsing the underlying evaluative framework. To explain how a person could be shamed by a criticism that itself has no epistemic weight because she thinks it is plain wrong, we will need to appeal to something other than a shared evaluative world view. I have suggested that this something else is the fact that in sharing a moral practice with us, others views come to have practical weight in the sense that they articulate moral interpretations of our character and actions that any number of others within the practice might share. At this point, defenders of the rst two strategies might object that my view does not seem very distant from their own. For them, vulnerability to feeling shamed hinges on which evaluative framework the agent endorses. They might go on to observe that endorsing the same evaluative framework that others do is just what makes us co-participants in a shared practice of morality. And while we may need to bring in something else to explain why particular criticisms shame, the fact that we endorse one evaluative framework rather than another sufciently explains why some people have the power to shame us and other people do not. We give practical weight to some criticismsincluding ones whose truth we denyprecisely because they issue from people whose evaluative commitments, skill at moral reasoning, and perceptive judgment command our respect. In short, defenders of the rst two strategies might give up the idea that particular criticisms must mirror the agents self-appraisals if they are to evoke shame. But they might still insist that the power to shame depends on the shamers evaluative and epistemic commitments mirroring the agents own.26 I agree that, typically, co-participants in a practice will endorse the same basic values and style of reasoning. But those who share a moral practice do not necessarily endorse the same evaluative standards. First, people do not usually choose to enter a practice of morality because they endorse its evaluative commitments and reasoning style. What people choose is to do something else with others, for example, work in academia. That choice moves them into an already ongoing moral practice.27 We thus come to share multiple practices of

26 This objection is a variant of one proposed to me by Jeffrey King. His particular concern was that what I call practical weight might ultimately reduce to epistemic weight. 27 Physicians, for example, do not choose to enter the social practice of morality that dominates the medical world. Rather, they choose to practice medicine with others and thereby nd themselves (re)located in an already ongoing moral practice.

AN APOLOGY FOR MORAL SHAME

143

morality with multiple groups of others for reasons often having little to do with our individual evaluative judgments. Second, as Margaret Walker has argued in her work on shared moral understandings, [t]o share terms in this sense need not mean that the terms in force are endorsed by all, much less that they exist by the consent of all who are required to recognize and respond to them.28 Members of subordinate groups quite often reject substantial chunks of the evaluative commitments, styles of reasoning, and assumptions about group difference embedded in the dominant social practice of morality. Even so, that dominant practice of morality generally continues to be one of the moral practices that members of subordinate groups share with others. To share a social practice means that one nds its moral understandings intelligible, even if not endorsable. One understands how people could come to think this way about moral matters. One understands what counts for others as acting responsibly, being truthful, being honorable, giving good moral advice, and so on.29 In short, the moral pioneer and discriminating social actor strategies place explanatory weight on the fact that the shamed person endorses something about the shamers evaluative perspective. I think the explanatory weight more properly belongs on the representativeness of the shamers viewpoint. What inspires shame is recognition of who we are for those with whom we share a moral practice. Within a shared practice of morality, those whose criticisms express a representative viewpoint have the power to shame. As a result, even if in ones own view one has nothing to be ashamed of, one may nevertheless have reason to feel ashamed.30 This means, unfortunately, that the power to shame is likely to be concentrated in the hands of those whose interpretations are socially authoritative. It is no accident that Adrian Piper nds herself shamed by a senior faculty member. His seniority, prominence within the profession, maleness, and whiteness work together to authorize his moral interpretation of her. In other cases, interpretations are socially authoritative because of their sheer conventionality; they express what generally goes without saying in a particular moral practice. Among doctors, for example, it goes without saying that physicians should never deliberately harm patients. Moral criticism of doctors who advocate active euthanasia thus has signicant shaming power.31 By contrast, those who lack social status or who voice controversial or idiosyncratic moral criticisms often lack the power to shame. This means that the power to

Margaret Walker, Moral Understandings (New York: Routledge, 1998), p. 63. The intelligibility of these moral interpretations is not a result of abstract understanding but of the fact that one does or has identied oneself with the social world from which those views emerge. 30 Rob Cummins suggested this distinction between You have nothing to be ashamed of and You ought not to feel ashamed. 31 Thanks to Gerald Dworkin for this example.

28 29

144

CHESHIRE CALHOUN

shame will typically be differentially distributed, tracking social status and what a group nds intuitively obvious.32 This is not good news for members of subordinate social groups. For example, in sexist societies, the power to shame will be disproportionately concentrated among men; and since ideologies about womens moral deciencies and the unreasonableness of protest typically underwrite sexist systems, vulnerability to being shamed will be disproportionately concentrated among women. Given this, one might naturally object that any apology for this often emotionally debilitating and demoralizing emotion is misplaced. Weparticularly the we who is socially subordinatemight be better off to train ourselves not to feel shame. This is not the simple objection that shame is an unpleasant feeling, so who needs it? Guilt, too, is an unpleasant feeling, yet it seems central to the fullbodied appreciation of moral error, to holding ourselves responsible,33 and to differentiating moral agents from psychopathological individuals.34 The objection here is that shame does not clearly serve any important moral function. Moreover, the burden of shame seems unfairly distributed in inegalitarian societies, serving only to further burden those who are already unfairly burdened. It is thus unclear what apology could be made for moral shame.35 Let me begin with the question of moral shames social function, and then turn to the concern that the power to shame and vulnerability to shame track social stratications. Morality is, in part, a critical, normative enterprise conducted by individuals who use their own best judgment to arrive at moral standards and practical conclusions, who seek the rationally best justications for their judgments, and who critically assess the standards and practical conclusions of both particular others and of social practices of morality. Shame, as I have characterized it, does not serve this dimension of the moral enterprise. Moral criticisms that we judge to be rationally indefensible may, I have argued, provoke shame. Shame thus does not second the critical normative judgments that we reach as autonomous, reective individuals. The enterprise of morality, however, is not just this reective, normative business of exercising ones own critical, autonomous judgment. Morality is also fundamentally a social enterprise.36 While hypothetical moral worlds of ideally rational agents are

32 Margaret Walker rightly points out that the moral intuitions appealed to by philosophers are just thatmoral intuitions of the social group philosophers. Other practices of morality might nd different claims intuitively obvious (Authority and Transparency in Moral Understandings). 33 Strawson argues that guilt, indignation and resentment are constitutive of what it means to hold ourselves and others morally accountable; P. F. Strawson, Freedom and Resentment, Free Will, ed. Gary Watson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982). 34 Jeffrie G. Murphy, Moral Death: A Kantian Essay on Psychopathy, Ethics and Personality: Essays in Moral Psychology, ed. John Deigh (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992). 35 I owe this criticism to Nancy Potter. 36 I have defended versions of this point in: The Virtue of Civility, Philosophy and Public Affairs, 29 (2000), 25175; Moral Failure, On Feminist Ethics and Politics, ed. Claudia Card (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1999); and Standing for Something, Journal of Philosophy, 92 (1995), 23560.

AN APOLOGY FOR MORAL SHAME

145

heuristically useful in evaluating the justiability of moral principles and norms, morality is only practiced in real social worlds. Morality regulates interactions between real social actors. Even if particular social practices of morality seem awed from the individuals critical, normative perspective, the social practice of morality is the only moral game in town. It is only in real social worlds that I have a moral identity. Who I am, morally, is who I am interpretable and identiable by others as being. That I fancy myself (even with what I take to be the best reasons) to be one kind of person rather than another does not give me an identity as that kind of person. Instead, the set of ones possible moral identities is delimited by the available moral interpretations within an ongoing moral practice. In insisting on the moral importance of remaining vulnerable to being shamed before others with whom we disagree, I have meant to be seconding a basic feminist claim, namely, that our selves are, in part, socially constructed and we need to take seriously that fact. So long as we participate in any moral practices at all, we will have some inescapable moral identities. They are inescapable, rst, because ones own self-conception does not decisively determine who one is. For any number of others within the moral practice of higher education, Piper was underhanded in refusing to pass as white. (Of course, in other practices, for example, the moral practice of her family, she was a person of integrity for refusing to pass as white.) Second, the identities that we have within particular moral practices are inescapable because we typically do not choose moral practices. What we choose are social practices of higher education, or medicine, or family life; we then nd ourselves located for better or worse in particular ongoing moral practices. In sum, shame is not the emotion of a critical, normatively reective, autonomous agent. Shame is the emotion of the practitioner of morality. To attempt to make oneself invulnerable to all shaming criticisms except those that mirror ones own autonomous judgments or that invoke ethical standards one respects is to refuse to take seriously the social practice of morality. And that, I have suggested, amounts to refusing to take morality seriously since the various social practices of morality are the only moral game in town. But what are we to do with the fact that dominant social groups monopolize the power to shame and subordinate social groups are excessively vulnerable to being shamed? As moral philosophers who have been trained to think of moral agents primarily as critically reective, autonomous persons, it is tempting to conclude that the subordinated would be best served by becoming more thickskinned and refusing to give others shaming criticisms practical weight. It is tempting, that is, to focus on altering the emotional responsiveness of the socially subordinate moral agent. This is a mistake. From both moral and political points of view, the social practice of morality needs to be taken more rather than less seriously. From a moral point of view, taking the social practice of morality seriously is central to taking morality seriously. Thus it is no error on the part

146

CHESHIRE CALHOUN

of the subordinated that they feel the practical weight of their fellow participants moral criticisms. From a political point of view, taking the social practice of morality seriously is central to the pursuit of social justice. Political discussion and public policy often repeat the same shaming criticisms that are part of everyday moral practice. The U.S. military policy of dont ask, dont tell, for example, clearly rests on the idea that same-sex desire is shameful and thus tolerable only if hidden. Political critiques of welfare and advocacy of workfare also often repeat widespread shaming criticisms of the poor as people who lazily live off the welfare system. Because shaming criticisms that articulate representative viewpoints are not something that people can just steel themselves against, we need to take very seriously the sexism, heterosexism, racism, and the like that are embedded in ongoing moral and political practices. We need to take seriously the deformed identities that the subordinate inhabit and the practical importance of contesting defective moral understandings and struggling to achieve their reform.37

37 Claudia Card defends this claim with respect to the defaming and demeaning identities to which gay men and lesbians are subjected in her Lesbian Choices (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), ch. 9.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Hope With or Without Faith: Kierkegaard on SufferingDocument16 paginiHope With or Without Faith: Kierkegaard on SufferingPEDRO HENRIQUE CRISTALDO SILVAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scheff - Shame and The Social Bond - A Sociological TheoryDocument17 paginiScheff - Shame and The Social Bond - A Sociological TheoryYulia Pro100% (1)

- Attachment Theory and The Evolutionary Psychology of Religion - Lee KirkpatrickDocument12 paginiAttachment Theory and The Evolutionary Psychology of Religion - Lee KirkpatrickBrett GustafsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alford, F. (1990) Reason and Reparation - A Kleinian Account of The Critique of Instrumental ReasonDocument26 paginiAlford, F. (1990) Reason and Reparation - A Kleinian Account of The Critique of Instrumental ReasonMiguel ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- UnderstandingGodimages PDFDocument14 paginiUnderstandingGodimages PDFAj HonorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bowlby - Psychology and DemocracyDocument16 paginiBowlby - Psychology and DemocracyRodrigo RobertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Condition of Black Life Is One of Mourning' - The New York TimesDocument10 paginiThe Condition of Black Life Is One of Mourning' - The New York TimesAnonymous FHCJucÎncă nu există evaluări

- What is Hate Speech? Conceptual AnalysisDocument50 paginiWhat is Hate Speech? Conceptual AnalysisLeons fÎncă nu există evaluări

- Forgiveness and Reconciliation. The Importance of Understanding How They DifferDocument17 paginiForgiveness and Reconciliation. The Importance of Understanding How They DifferpetrusgrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internal Racism A Psychoanalytic Approach To Race and Difference, Stephens & Alanson 2014Document3 paginiInternal Racism A Psychoanalytic Approach To Race and Difference, Stephens & Alanson 2014Ambrose66100% (1)

- On Suffering: Philosophical Reflections On What It Means To Be HumanDocument1 paginăOn Suffering: Philosophical Reflections On What It Means To Be HumanRobin KelleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shame Binding Affect Ego State Contamination and Relational RepairDocument9 paginiShame Binding Affect Ego State Contamination and Relational RepairIrina Catalina Tudorascu100% (1)

- Shame & Guilt - by Ernest Kurtz: Historical Perspective For Professionals) - Center City, Minnesota: Hazelden 1981Document32 paginiShame & Guilt - by Ernest Kurtz: Historical Perspective For Professionals) - Center City, Minnesota: Hazelden 1981CristianThieryÎncă nu există evaluări

- De Ontologizing God FaberDocument15 paginiDe Ontologizing God FaberproklosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mcgrath Schelling Freudian PDFDocument20 paginiMcgrath Schelling Freudian PDFMichalJanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kierkegaard's Account of Ethical TransformationDocument30 paginiKierkegaard's Account of Ethical TransformationMads Peter KarlsenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Existentialism (First Published As 'Dreadful Freedom') (1984)Document160 paginiIntroduction To Existentialism (First Published As 'Dreadful Freedom') (1984)Lukas KahnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fromm's Humanistic Psychoanalysis - Case StudyDocument6 paginiFromm's Humanistic Psychoanalysis - Case StudyLily ManobanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Displacing CastrationDocument27 paginiDisplacing Castrationamiller1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Psychoanalysis Listens to its DeathDocument7 paginiPsychoanalysis Listens to its DeathAL KENATÎncă nu există evaluări

- Orientations Toward Death: A Vital Aspect of The Study of Lives by Edwin S. Shneidman 1963Document28 paginiOrientations Toward Death: A Vital Aspect of The Study of Lives by Edwin S. Shneidman 1963jhobegiÎncă nu există evaluări

- What it means to lose hopeDocument18 paginiWhat it means to lose hopePaola QuiñonesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rogers and Kohut A Historical Perspective Psicoanalytic Psychology PDFDocument21 paginiRogers and Kohut A Historical Perspective Psicoanalytic Psychology PDFSilvana HekierÎncă nu există evaluări

- Erich Fromm - Concept of Social CharacterDocument8 paginiErich Fromm - Concept of Social CharacterGogutaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hefferman, Ekphrasis and RepresentationDocument21 paginiHefferman, Ekphrasis and RepresentationAgustín AvilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frosh2018 - Rethinking Psychoanalysis in The PsychosocialDocument10 paginiFrosh2018 - Rethinking Psychoanalysis in The PsychosocialAnonymous DMoxQS65tÎncă nu există evaluări

- Explain and Assess Nietzsche's Claim That The World Is Will To Power and Nothing Besides'Document5 paginiExplain and Assess Nietzsche's Claim That The World Is Will To Power and Nothing Besides'Patricia VillyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kirkman-Psychopaths Who Live Among UsDocument18 paginiKirkman-Psychopaths Who Live Among UsANA MATILDE BIEBERACH VANEGASÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alan Bass Interpretation and DifferenceDocument217 paginiAlan Bass Interpretation and DifferenceValeria Campos SalvaterraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Social Reality of Truth - Foucault, Searle and The Role of Truth Within Social Reality - Masters Tesis PDFDocument52 paginiThe Social Reality of Truth - Foucault, Searle and The Role of Truth Within Social Reality - Masters Tesis PDFMarcelo Endres100% (1)

- The Phenomenology of TraumaDocument4 paginiThe Phenomenology of TraumaMelayna Haley0% (1)

- Winnicott ch1 PDFDocument18 paginiWinnicott ch1 PDFAlsabila NcisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edson - Theological HumanismDocument14 paginiEdson - Theological Humanismanna_andrea_5Încă nu există evaluări

- Sociology of BoredomDocument27 paginiSociology of Boredomsushilyati67% (3)

- Duty and The Death of DesireDocument25 paginiDuty and The Death of DesireDave GreenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Creativity: A New Paradigm For Freudian Psychoanalysis René RoussillonDocument21 paginiCreativity: A New Paradigm For Freudian Psychoanalysis René RoussillonnosoyninjaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Description of Karen Horney's Neo-Freudian Theory of PersonalityDocument3 paginiA Description of Karen Horney's Neo-Freudian Theory of PersonalityTamizharasi UdhayasuriyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 112200921441852&&on Violence (Glasser)Document20 pagini112200921441852&&on Violence (Glasser)Paula GonzálezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Martha C. Nussbaum - Précis of Upheavals of ThoughtDocument7 paginiMartha C. Nussbaum - Précis of Upheavals of Thoughtahnp1986Încă nu există evaluări

- Narratives of the Self - How Stories Shape our IdentitiesDocument13 paginiNarratives of the Self - How Stories Shape our IdentitiesAlejandro Hugo GonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rollo Reese May and Theories of Personality Philosophy EssayDocument7 paginiRollo Reese May and Theories of Personality Philosophy EssayMary Anne Aguas AlipaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fides Et Ratio As The Perpetual Journey of Faith and ReasonDocument23 paginiFides Et Ratio As The Perpetual Journey of Faith and ReasonClarensia AdindaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychodynamic Approaches: Freud's Influence on BehaviorDocument12 paginiPsychodynamic Approaches: Freud's Influence on BehaviorFranco Fabricio CarpioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Autonomy, Heteronomy and Moral ImperativesDocument14 paginiAutonomy, Heteronomy and Moral ImperativesjuanamaldonadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hoffman - The Myths of Free AssociationDocument20 paginiHoffman - The Myths of Free Association10961408Încă nu există evaluări

- The Philosophy of Love - 1010Document6 paginiThe Philosophy of Love - 1010api-270742045Încă nu există evaluări

- Marx's Ethics Grounded in Human Self-RealizationDocument28 paginiMarx's Ethics Grounded in Human Self-RealizationMiguel ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inheriting the Future: Legacies of Kant, Freud, and FlaubertDe la EverandInheriting the Future: Legacies of Kant, Freud, and FlaubertÎncă nu există evaluări

- A. Johnston - Naturalism and Anti NaturalismDocument47 paginiA. Johnston - Naturalism and Anti NaturalismaguiaradÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Interview With Adam PhillipsDocument17 paginiAn Interview With Adam Phillipsthanoskafka100% (2)

- Nussbaum, Martha. ObjectificationDocument43 paginiNussbaum, Martha. ObjectificationNicoletta Marini-Maio100% (1)

- Phenomenological Method OutlineDocument3 paginiPhenomenological Method OutlineGalvez, Anya Faith Q.Încă nu există evaluări

- Cognitive Dissonance TheoryDocument3 paginiCognitive Dissonance TheoryJelena RodicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Role Transitions, Objects, and IdentityDocument20 paginiRole Transitions, Objects, and IdentityaitorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jean Laplanche - 'The So-Called 'Death Drive' - A Sexual Drive', British Journal of Psychotherapy, 20 (4), 2004Document18 paginiJean Laplanche - 'The So-Called 'Death Drive' - A Sexual Drive', British Journal of Psychotherapy, 20 (4), 2004scottbrodieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Helen Morgan - Living in Two Worlds - How Jungian' Am IDocument9 paginiHelen Morgan - Living in Two Worlds - How Jungian' Am IguizenhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wittgensteinian Faith and ReasonDocument15 paginiWittgensteinian Faith and ReasonCally docÎncă nu există evaluări

- Love and Its Discontents: Irony, Reason, RomanceDocument15 paginiLove and Its Discontents: Irony, Reason, RomanceGong ChenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essays On Pragmatic Naturalism: Discourse Relativity, Religion, Art, and EducationDe la EverandEssays On Pragmatic Naturalism: Discourse Relativity, Religion, Art, and EducationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Protasi, Sara, Varieties of EnvyDocument16 paginiProtasi, Sara, Varieties of EnvyRocío Cázares100% (1)

- Bernard Williams, Life As NarrativeDocument11 paginiBernard Williams, Life As NarrativeRocío CázaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phillips, D. Z., The Limitations of Miss Anscome S GrocerDocument4 paginiPhillips, D. Z., The Limitations of Miss Anscome S GrocerRocío CázaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is Efficiency A Vice (Kieran Setiya)Document7 paginiIs Efficiency A Vice (Kieran Setiya)Rocío Cázares100% (1)

- Wallace, R. Jay, Responsibility and The Moral SentimentsDocument211 paginiWallace, R. Jay, Responsibility and The Moral SentimentsRocío Cázares100% (1)

- Nietzsche's Minimalist Moral PsychologyDocument11 paginiNietzsche's Minimalist Moral PsychologyTerry BoydÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moller, Dan - Anticipated Emotions and Emotional ValenceDocument1 paginăMoller, Dan - Anticipated Emotions and Emotional ValenceRocío CázaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seneca - Moral and Political EssaysDocument367 paginiSeneca - Moral and Political EssaysRocío CázaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monogamy Non MonogamyDocument18 paginiMonogamy Non MonogamyRocío CázaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aota Professional Development ToolDocument2 paginiAota Professional Development Toolapi-436821531100% (1)

- First Quarter Exam: Grade 11 Oral CommunicationDocument4 paginiFirst Quarter Exam: Grade 11 Oral CommunicationJaycher BagnolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Obstacles and Pitfalls in Development Path: Unit-IiDocument10 paginiObstacles and Pitfalls in Development Path: Unit-IipradeepÎncă nu există evaluări

- My Portfolio: Marie Antonette S. NicdaoDocument10 paginiMy Portfolio: Marie Antonette S. NicdaoLexelyn Pagara RivaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Importance of Community: Pre-ReadingDocument5 paginiThe Importance of Community: Pre-ReadingRaqueal HenryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Graduation 2017 Graduation List Final SinagtalaDocument36 paginiGraduation 2017 Graduation List Final SinagtalaJohn Glenn CasinilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2011 Korean Government Scholarship Program GuidelineDocument35 pagini2011 Korean Government Scholarship Program GuidelinepinalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extensive Reading TrueDocument9 paginiExtensive Reading TrueMarni HuluÎncă nu există evaluări

- THỰC HÀNH CHUYÊN ĐỀ TRỌNG ÂMDocument3 paginiTHỰC HÀNH CHUYÊN ĐỀ TRỌNG ÂMNguyen Viet LovesUlisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Substance Use ResumeDocument2 paginiSubstance Use Resumeapi-576594451Încă nu există evaluări

- Body PercussionDocument3 paginiBody Percussiondl1485100% (1)

- Nutrition Action Plan for Hulo Integrated SchoolDocument5 paginiNutrition Action Plan for Hulo Integrated SchoolJas MinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Updated NcaDocument1.769 paginiUpdated NcaSaluibTanMelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art of Design v2Document337 paginiArt of Design v2lintodd100% (1)

- Vijeo Citect VCCP VCCE FlyerDocument2 paginiVijeo Citect VCCP VCCE FlyerRicardo FonsecaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Activity Design For GADDocument4 paginiActivity Design For GADFers PinedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exist 2 Inspire PDFDocument2 paginiExist 2 Inspire PDFCraig100% (1)

- Meeting 1Document34 paginiMeeting 1Josep PeterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Naikembot NaDocument137 paginiNaikembot NaMeloida BiscarraÎncă nu există evaluări

- LE-English-Grade 9-Q1-MELC 3Document6 paginiLE-English-Grade 9-Q1-MELC 3Krizia Mae D. Pineda100% (1)

- Transportation Alphabet PDFDocument27 paginiTransportation Alphabet PDFAprendendo a Aprender Inglês com a TassiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notice 1576650533Document4 paginiNotice 1576650533M ASHIBUR RAHMANÎncă nu există evaluări

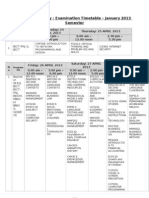

- Examination Timetable - January 2013 SemesterDocument4 paginiExamination Timetable - January 2013 SemesterWhitney CantuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cross Cultural UnderstandingDocument3 paginiCross Cultural UnderstandingHanik BachtiarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art2 CurmapDocument9 paginiArt2 Curmapruclito morataÎncă nu există evaluări

- FORM 138 Kto12 ElementaryDocument2 paginiFORM 138 Kto12 ElementaryKat Causaren Landrito0% (1)

- Lecturer Agada TantraDocument2 paginiLecturer Agada TantraKirankumar MutnaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Build Business Models Sample Syllabus 40chDocument0 paginiBuild Business Models Sample Syllabus 40chlilbouyinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edgbaston Campus MapDocument6 paginiEdgbaston Campus MapMaziar MehravarÎncă nu există evaluări

- DLP Format EnglishDocument3 paginiDLP Format EnglishNormina MamaÎncă nu există evaluări