Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Essays by The Late David Foster Wallace

Încărcat de

irynekaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

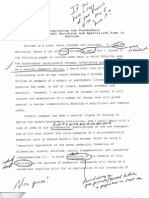

Essays by The Late David Foster Wallace

Încărcat de

irynekaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

CONSIDER THE LOBSTER

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED AUGUST 2004

For 56 years, the Maine Lobster Festival has been drawing crowds with the promise of sun, fun, and fine food. One visitor would argue that the celebration involves a whole lot more.

The enormous, pungent, and extremely well marketed Maine Lobster Festival is held every late July in the states midcoast region, meaning the western side of Penobscot Bay, the nerve stem of Maines lobster industry. Whats called the midcoast runs from Owls Head and Thomaston in the south to Belfast in the north. (Actually, it might extend all the way up to Bucksport, but we were never able to get farther north than Belfast on Route 1, whose summer traffic is, as you can imagine, unimaginable.) The regions two main communities are Camden, with its very old money and yachty harbor and five-star restaurants and phenomenal B&Bs, and Rockland, a serious old fishing town that hosts the Festival every summer in historic Harbor Park, right along the water.1

Tourism and lobster are the midcoast regions two main industries, and theyre both warm-weather enterprises, and the Maine Lobster Festival represents less an intersection of the industries than a deliberate collision, joyful and lucrative and loud. The assigned subject of this article is the 56th Annual MLF, July 30 to August 3, 2003, whose official theme was Lighthouses, Laughter, and Lobster. Total paid attendance was over 80,000, due partly to a national CNN spot in June during which a Senior Editor of a certain other epicurean magazine hailed the MLF as one of the best food-themed festivals in the world. 2003 Festival highlights: concerts by Lee Ann Womack and Orleans, annual Maine Sea Goddess beauty pageant, Saturdays big parade, Sundays William G. Atwood Memorial Crate Race, annual Amateur Cooking Competition, carnival rides and midway attractions and food booths, and the MLFs Main Eating Tent, where something over 25,000 pounds of fresh-caught Maine lobster is consumed after preparation in the Worlds Largest Lobster Cooker near the grounds north entrance. Also available are lobster rolls, lobster turnovers, lobster saut, Down East lobster salad, lobster bisque, lobster ravioli, and deep-fried lobster dumplings. Lobster Thermidor is obtainable at a sit-down restaurant called The Black Pearl on Harbor Parks northwest wharf. A large all-pine booth sponsored by the Maine Lobster Promotion Council has free pamphlets with recipes, eating tips, and Lobster Fun Facts. The winner of Fridays Amateur Cooking Competition prepares Saffron Lobster Ramekins, the recipe for which is available for public downloading at www.mainelobsterfestival.com. There are lobster T-shirts and lobster bobblehead dolls and inflatable lobster pool toys and clamp-on lobster hats with big scarlet claws that wobble on springs. Your assigned correspondent saw it all, accompanied by one girlfriend and both his own parentsone of which parents was actually born and raised in Maine, albeit in the extreme northern inland part, which is potato country and a world away from the touristic midcoast.2

For practical purposes, everyone knows what a lobster is. As usual, though, theres much more to know than most of us care aboutits all a matter of what your interests are. Taxonomically speaking, a lobster is a marine crustacean of the family Homaridae, characterized by five pairs of jointed legs, the first pair terminating in large pincerish claws used for subduing prey. Like many other species of benthic carnivore, lobsters are both hunters and scavengers. They have stalked eyes, gills on their legs, and antennae. There are dozens of different kinds worldwide, of which the relevant species here is the Maine lobster, Homarus americanus. The name lobster comes from the Old English loppestre, w hich is thought to be a corrupt form of the Latin word for locust combined with the Old English loppe, which meant spider.

Moreover, a crustacean is an aquatic arthropod of the class Crustacea, which comprises crabs, shrimp, barnacles, lobsters, and freshwater crayfish. All this is right there in the encyclopedia. And an arthropod is an invertebrate member of the phylum Arthropoda, which phylum covers insects, spiders, crustaceans, and centipedes/millipedes, all of whose main commonality, besides the absence of a centralized brain-spine assembly, is a chitinous exoskeleton composed of segments, to which appendages are articulated in pairs.

The point is that lobsters are basically giant sea-insects.3 Like most arthropods, they date from the Jurassic period, biologically so much older than mammalia that they might as well be from another planet. And they areparticularly in their natural brown-green state, brandishing their claws like weapons and with thick antennae awhipnot nice to look at. And its true that they are garbagemen of the sea, eaters of dead stuff,4 although theyll also eat some live shellfish, certain kinds of injured fish, and sometimes each other.

But they are themselves good eating. Or so we think now. Up until sometime in the 1800s, though, lobster was literally low-class food, eaten only by the poor and institutionalized. Even in the harsh penal environment of early America, some colonies had laws against feeding lobsters to inmates more than once a week because it was thought to be cruel and unusual, like making people eat rats. One reason for their low status was how plentiful lobsters were in old New England. Unbelievable abundance is how one source describes the situation, including accounts of Plymouth pilgrims wading out and capturing all they wanted by hand, and of early Bostons seashore being littered with lobsters after hard storms these latter were treated as a smelly nuisance and ground up for fertilizer. There is also the fact that premodern lobster was often cooked dead and then preserved, usually packed in salt or crude hermetic containers. Maines earliest lobster industry was based around a dozen such seaside canneries in the 1840s, from which lobster was shipped as far away as California, in demand only because it was cheap and high in protein, basically chewable fuel.

Now, of course, lobster is posh, a delicacy, only a step or two down from caviar. The meat is richer and more substantial than most fish, its taste subtle compared to the marine-gaminess of mussels and clams. In the U.S. pop-food imagination, lobster is now the seafood analog to steak, with which its so often twinned as Surf n Turf on the really expensive part of the chain steak house menu.

In fact, one obvious project of the MLF, and of its omnipresently sponsorial Maine Lobster Promotion Council, is to counter the idea that lobster is unusually luxe or rich or unhealthy or expensive, suitable only for effete palates or the occasional blow-the-diet treat. It is emphasized over and over in presentations and pamphlets at the Festival that Maine lobster meat has fewer calories, less cholesterol, and less saturated fat than chicken.5 And in the Main Eating Tent, you can get a quarter (industry shorthand for a 1-pound lobster), a 4-ounce cup of melted butter, a bag of chips, and a soft roll w/ butter-pat for around $12.00, which is only slightly more expensive than supper at McDonalds.

Be apprised, though, that the Main Eating Tents suppers come in Styrofoam trays, and the soft drinks are iceless and flat, and the coffee is convenience-store coffee in yet more Styrofoam, and the utensils are plastic (there are none of the special long skinny forks for pushing out the tail meat, though a few savvy diners bring their own). Nor do they give you near enough napkins, considering how messy lobster is to eat, especially when youre squeezed onto benches alongside children of various ages and vastly different levels of fine-motor developmentnot to mention the people whove somehow smuggled in their own beer in enormous aisle-blocking coolers, or who all of a sudden produce their own plastic tablecloths and try to spread them over large portions of tables to try to reserve them (the tables) for their little groups. And so on. Any one example is no more than a petty inconvenience, of course, but the MLF turns out to be full of irksome little downers like thissee for instance the Main Stages headliner shows, where it turns out that you have to pay $20 extra for a folding chair if you want to sit down; or the North Tents mad scramble for the NyQuil-cup-size samples of finalists entries handed out after the Cooking Competition; or the much-touted Maine Sea Goddess pageant finals, which turn out to be excruciatingly long and to consist mainly of endless thanks and tributes to local sponsors. What the Maine Lobster Festival really is is a midlevel county fair with a culinary hook, and in this respect its not unlike Tidewater crab festivals, Midwest corn festivals, Texas chili festivals, etc., and shares with these venues the core paradox of all teeming commercial demotic events: Its not for everyone.6 Nothing against the aforementioned euphoric Senior Editor, but Id be surprised if shed spent much time here in Harbor Park, watching people slap canal-zone mosquitoes as they eat deep-fried Twinkies and watch Professor Paddywhack, on six-foot stilts in a raincoat with plastic lobsters protruding from all directions on springs, terrify their children.

Lobster is essentially a summer food. This is because we now prefer our lobsters fresh, which means they have to be recently caught, which for both tactical and economic reasons takes place at depths of less than 25 fathoms. Lobsters tend to be hungriest and most active (i.e., most trappable) at summer

water temperatures of 4550F. In the autumn, some Maine lobsters migrate out into deeper water, either for warmth or to avoid the heavy waves that pound New Englands coast all winter. Some burrow into the bottom. They might hibernate; nobodys sure. Summer is also lobsters molting season specifically early- to mid-July. Chitinous arthropods grow by molting, rather the way people have to buy bigger clothes as they age and gain weight. Since lobsters can live to be over 100, they can also get to be quite large, as in 20 pounds or morethough truly senior lobsters are rare now, because New Englands waters are so heavily trapped.7 Anyway, hence the culinary distinction between hard- and soft-shell lobsters, the latter sometimes a.k.a. shedders. A soft-shell lobster is one that has recently molted. In midcoast restaurants, the summer menu often offers both kinds, with shedders being slightly cheaper even though theyre easier to dismantle and the meat is allegedly sweeter. The reason for the discount is that a molting lobster uses a layer of seawater for insulation while its new shell is hardening, so theres slightly less actual meat when you crack open a shedder, plus a redolent gout of water that gets all over everything and can sometimes jet out lemonlike and catch a tablemate right in the eye. If its winter or youre buying lobster someplace far from New England, on the other hand, you can almost bet that the lobster is a hard-shell, which for obvious reasons travel better.

As an la carte entre, lobster can be baked, broiled, steamed, grilled, sauted, stir-fried, or microwaved. The most common method, though, is boiling. If youre someone who enjoys having lobster at home, this is probably the way you do it, since boiling is so easy. You need a large kettle w/ cover, which you fill about half full with water (the standard advice is that you want 2.5 quarts of water per lobster). Seawater is optimal, or you can add two tbsp salt per quart from the tap. It also helps to know how much your lobsters weigh. You get the water boiling, put in the lobsters one at a time, cover the kettle, and bring it back up to a boil. Then you bank the heat and let the kettle simmerten minutes for the first pound of lobster, then three minutes for each pound after that. (This is assuming youve got hard-shell lobsters, which, again, if you dont live between Boston and Halifax, is probably what youve got. For shedders, youre supposed to subtract three minutes from the total.) The reason the kettles lobsters turn scarlet is that boiling somehow suppresses every pigment in their chitin but one. If you want an easy test of whether the lobsters are done, you try pulling on one of their antennaeif it comes out of the head with minimal effort, youre ready to eat.

A detail so obvious that most recipes dont even bother to mention it is that each lobster is supposed to be alive when you put it in the kettle. This is part of lobsters modern appeal: Its the freshest food there is. Theres no decomposition between harvesting and eating. And not only do lobsters require no cleaning or dressing or plucking (though the mechanics of actually eating them are a different matter), but theyre relatively easy for vendors to keep alive. They come up alive in the traps, are placed in containers of seawater, and can, so long as the waters aerated and the animals claws are pegged or banded to keep them from tearing one another up under the stresses of captivity,8 survive right up until theyre boiled. Most of us have been in supermarkets or restaurants that feature tanks of live lobster, from which you can pick out your supper while it watches you point. And part of the overall spectacle of

the Maine Lobster Festival is that you can see actual lobstermens vessels docking at the wharves along the northeast grounds and unloading freshly caught product, which is transferred by hand or cart 100 yards to the great clear tanks stacked up around the Festivals cookerwhich is, as mentioned, billed as the Worlds Largest Lobster Cooker and can process over 100 lobsters at a time for the Main Eating Tent.

So then here is a question thats all but unavoidable at the Worlds Largest Lobster Cooker, and may arise in kitchens across the U.S.: Is it all right to boil a sentient creature alive just for our gustatory pleasure? A related set of concerns: Is the previous question irksomely PC or sentimental? What does all right even mean in this context? Is it all just a matter of individual choice?

As you may or may not know, a certain well-known group called People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals thinks that the morality of lobster-boiling is not just a matter of individual conscience. In fact, one of the very first things we hear about the MLF well, to set the scene: Were coming in by cab from the almost indescribably odd and rustic Knox County Airport9 very late on the night before the Festival opens, sharing the cab with a wealthy political consultant who lives on Vinalhaven Island in the bay half the year (hes headed for the island ferry in Rockland). The consultant and cabdriver are responding to informal journalistic probes about how people who live in the midcoast region actually view the MLF, as in is the Festival just a big-dollar tourist thing or is it something local residents look forward to attending, take genuine civic pride in, etc. The cabdriverwhos in his seventies, one of apparently a whole platoon of retirees the cab company puts on to help with the summer rush, and wears a U.S.-flag lapel pin, and drives in what can only be called a very deliberate wayassures us that locals do endorse and enjoy the MLF, although he himself hasnt gone in years, and now come to think of it no one he and his wife know has, either. However, the demilocal consultants been to recent Festivals a couple times (one gets the impression it was at his wifes behest), of which his most vivid impression was that you have to line up for an ungodly long time to get your lobsters, and meanwhile there are all these exflower children coming up and down along the line handing out pamphlets that say the lobsters die in terrible pain and you shouldnt eat them.

And it turns out that the post-hippies of the consultants recollection were activists from PETA. There were no PETA people in obvious view at the 2003 MLF,10 but theyve been conspicuous at many of the recent Festivals. Since at least the mid-1990s, articles in everything from The Camden Herald to The New York Times have described PETA urging boycotts of the MLF, often deploying celebrity spokespeople like Mary Tyler Moore for open letters and ads saying stuff like Lobsters are extraordinarily sensitive and To me, eating a lobster is out of the question. More concrete is the oral testimony of Dick, our florid and extremely gregarious rental-car guy, to the effect that PETAs been around so much in recent years that a kind of brittlely tolerant homeostasis now obtains between the activists and the Festivals locals, e.g.: We had some incidents a couple years ago. One lady took most of her clothes off and painted

herself like a lobster, almost got herself arrested. But for the most part theyre let alone. *Rapid series of small ambiguous laughs, which with Dick happens a lot.+ They do their thing and we do our thing.

This whole interchange takes place on Route 1, 30 July, during a four-mile, 50-minute ride from the airport11 to the dealership to sign car-rental papers. Several irreproducible segues down the road from the PETA anecdotes, Dickwhose son-in-law happens to be a professional lobsterman and one of the Main Eating Tents regular suppliersarticulates what he and his family feel is the crucial mitigating factor in the whole morality-of-boiling-lobsters-alive issue: Theres a part of the brain in people and animals that lets us feel pain, and lobsters brains dont have this part.

Besides the fact that its incorrect in about 11 different ways, the main reason Dicks statement is interesting is that its thesis is more or less echoed by the Festivals own pronouncement on lobsters and pain, which is part of a Test Your Lobster IQ quiz that appears in the 2003 MLF program courtesy of the Maine Lobster Promotion Council: The nervous system of a lobster is very simple, and is in fact most similar to the nervous system of the grasshopper. It is decentralized with no brain. There is no cerebral cortex, which in humans is the area of the brain that gives the experience of pain.

Though it sounds more sophisticated, a lot of the neurology in this latter claim is still either false or fuzzy. The human cerebral cortex is the brain-part that deals with higher faculties like reason, metaphysical self-awareness, language, etc. Pain reception is known to be part of a much older and more primitive system of nociceptors and prostaglandins that are managed by the brain stem and thalamus.12 On the other hand, it is true that the cerebral cortex is involved in whats variously called suffering, distress, or the emotional experience of paini.e., experiencing painful stimuli as unpleasant, very unpleasant, unbearable, and so on.

Before we go any further, lets acknowledge that the questions of whether and how different kinds of animals feel pain, and of whether and why it might be justifiable to inflict pain on them in order to eat them, turn out to be extremely complex and difficult. And comparative neuroanatomy is only part of the problem. Since pain is a totally subjective mental experience, we do not have direct access to anyone or anythings pain but our own; and even just the principles by which we can infer that others experience pain and have a legitimate interest in not feeling pain involve hard-core philosophymetaphysics, epistemology, value theory, ethics. The fact that even the most highly evolved nonhuman mammals cant use language to communicate with us about their subjective mental experience is only the first layer of additional complication in trying to extend our reasoning about pain and morality to animals. And everything gets progressively more abstract and convolved as we move farther and farther out from

the higher-type mammals into cattle and swine and dogs and cats and rodents, and then birds and fish, and finally invertebrates like lobsters.

The more important point here, though, is that the whole animal-cruelty-and-eating issue is not just complex, its also uncomfortable. It is, at any rate, uncomfortable for me, and for just about everyone I know who enjoys a variety of foods and yet does not want to see herself as cruel or unfeeling. As far as I can tell, my own main way of dealing with this conflict has been to avoid thinking about the whole unpleasant thing. I should add that it appears to me unlikely that many readers of gourmet wish to think hard about it, either, or to be queried about the morality of their eating habits in the pages of a culinary monthly. Since, however, the assigned subject of this article is what it was like to attend the 2003 MLF, and thus to spend several days in the midst of a great mass of Americans all eating lobster, and thus to be more or less impelled to think hard about lobster and the experience of buying and eating lobster, it turns out that there is no honest way to avoid certain moral questions.

There are several reasons for this. For one thing, its not just that lobsters get boiled alive, its that you do it yourselfor at least its done specifically for you, on-site.13 As mentioned, the Worlds Largest Lobster Cooker, which is highlighted as an attraction in the Festivals program, is right out there on the MLFs north grounds for everyone to see. Try to imagine a Nebraska Beef Festival14 at which part of the festivities is watching trucks pull up and the live cattle get driven down the ramp and slaughtered right there on the Worlds Largest Killing Floor or somethingtheres no way.

The intimacy of the whole thing is maximized at home, which of course is where most lobster gets prepared and eaten (although note already the semiconscious euphemism prepared, which in the case of lobsters really means killing them right there in our kitchens). The basic scenario is that we come in from the store and make our little preparations like getting the kettle filled and boiling, and then we lift the lobsters out of the bag or whatever retail container they came home in whereupon some uncomfortable things start to happen. However stuporous the lobster is from the trip home, for instance, it tends to come alarmingly to life when placed in boiling water. If youre tilting it from a container into the steaming kettle, the lobster will sometimes try to cling to the containers sides or even to hook its claws over the kettles rim like a person trying to keep from going over the edge of a roof. And worse is when the lobsters fully immersed. Even if you cover the kettle and turn away, you can usually hear the cover rattling and clanking as the lobster tries to push it off. Or the creatures claws scraping the sides of the kettle as it thrashes around. The lobster, in other words, behaves very much as you or I would behave if we were plunged into boiling water (with the obvious exception of screaming).15 A blunter way to say this is that the lobster acts as if its in terrible pain, causing some cooks to leave the kitchen altogether and to take one of those little lightweight plastic oven timers with them into another room and wait until the whole process is over.

There happen to be two main criteria that most ethicists agree on for determining whether a living creature has the capacity to suffer and so has genuine interests that it may or may not be our moral duty to consider.16 One is how much of the neurological hardware required for pain-experience the animal comes equipped withnociceptors, prostaglandins, neuronal opioid receptors, etc. The other criterion is whether the animal demonstrates behavior associated with pain. And it takes a lot of intellectual gymnastics and behaviorist hairsplitting not to see struggling, thrashing, and lid-clattering as just such pain-behavior. According to marine zoologists, it usually takes lobsters between 35 and 45 seconds to die in boiling water. (No source I could find talked about how long it takes them to die in superheated steam; one rather hopes its faster.)

There are, of course, other fairly common ways to kill your lobster on-site and so achieve maximum freshness. Some cooks practice is to drive a sharp heavy knife point-first into a spot just above the midpoint between the lobsters eyestalks (more or less where the Third Eye is in human foreheads). This is alleged either to kill the lobster instantly or to render it insensateand is said at least to eliminate the cowardice involved in throwing a creature into boiling water and then fleeing the room. As far as I can tell from talking to proponents of the knife-in-the-head method, the idea is that its more violent but ultimately more merciful, plus that a willingness to exert personal agency and accept responsibility for stabbing the lobsters head honors the lobster somehow and entitles one to eat it. (Theres often a vague sort of Native American spirituality-of-the-hunt flavor to pro-knife arguments.) But the problem with the knife method is basic biology: Lobsters nervous systems operate off not one but several ganglia, a.k.a. nerve bundles, which are sort of wired in series and distributed all along the lobsters underside, from stem to stern. And disabling only the frontal ganglion does not normally result in quick death or unconsciousness. Another alternative is to put the lobster in cold salt water and then very slowly bring it up to a full boil. Cooks who advocate this method are going mostly on the analogy to a frog, which can supposedly be kept from jumping out of a boiling pot by heating the water incrementally. In order to save a lot of research-summarizing, Ill simply assure you that the analogy between frogs and lobsters turns out not to hold.

Ultimately, the only certain virtues of the home-lobotomy and slow-heating methods are comparative, because there are even worse/crueler ways people prepare lobster. Time-thrifty cooks sometimes microwave them alive (usually after poking several extra vent holes in the carapace, which is a precaution most shellfish-microwavers learn about the hard way). Live dismemberment, on the other hand, is big in Europe: Some chefs cut the lobster in half before cooking; others like to tear off the claws and tail and toss only these parts in the pot.

And theres more unhappy news respecting suffering-criterion number one. Lobsters dont have much in the way of eyesight or hearing, but they do have an exquisite tactile sense, one facilitated by hundreds of thousands of tiny hairs that protrude through their carapace. Thus, in the words of T.M. Pruddens industry classic About Lobster, it is that although encased in what seems a solid, impenetrable armor, the lobster can receive stimuli and impressions from without as readily as if it possessed a soft and delicate skin. And lobsters do have nociceptors,17 as well as invertebrate versions of the prostaglandins and major neurotransmitters via which our own brains register pain.

Lobsters do not, on the other hand, appear to have the equipment for making or absorbing natural opioids like endorphins and enkephalins, which are what more advanced nervous systems use to try to handle intense pain. From this fact, though, one could conclude either that lobsters are maybe even more vulnerable to pain, since they lack mammalian nervous systems built-in analgesia, or, instead, that the absence of natural opioids implies an absence of the really intense pain-sensations that natural opioids are designed to mitigate. I for one can detect a marked upswing in mood as I contemplate this latter possibility: It could be that their lack of endorphin/enkephalin hardware means that lobsters raw subjective experience of pain is so radically different from mammals that it may not even deserve the term pain. Perhaps lobsters are more like those frontal-lobotomy patients one reads about who report experiencing pain in a totally different way than you and I. These patients evidently do feel physical pain, neurologically speaking, but dont dislike itthough neither do they like it; its more that they feel it but dont feel anything about itthe point being that the pain is not distressing to them or something they want to get away from. Maybe lobsters, who are also without frontal lobes, are detached from the neurological-registration-of-injury-or-hazard we call pain in just the same way. There is, after all, a difference between (1) pain as a purely neurological event, and (2) actual suffering, which seems crucially to involve an emotional component, an awareness of pain as unpleasant, as something to fear/dislike/want to avoid.

Still, after all the abstract intellection, there remain the facts of the frantically clanking lid, the pathetic clinging to the edge of the pot. Standing at the stove, it is hard to deny in any meaningful way that this is a living creature experiencing pain and wishing to avoid/escape the painful experience. To my lay mind, the lobsters behavior in the kettle appears to be the expression of a preference; and it may well be that an ability to form preferences is the decisive criterion for real suffering.18 The logic of this (preference p suffering) relation may be easiest to see in the negative case. If you cut certain kinds of worms in half, the halves will often keep crawling around and going about their vermiform business as if nothing had happened. When we assert, based on their post-op behavior, that these worms appear not to be suffering, what were really saying is that theres no sign that the worms know anything bad has happened or would prefer not to have gotten cut in half.

Lobsters, however, are known to exhibit preferences. Experiments have shown that they can detect changes of only a degree or two in water temperature; one reason for their complex migratory cycles (which can often cover 100-plus miles a year) is to pursue the temperatures they like best.19 And, as mentioned, theyre bottom-dwellers and do not like bright light: If a tank of food lobsters is out in the sunlight or a stores fluorescence, the lobsters will always congregate in whatever part is darkest. Fairly solitary in the ocean, they also clearly dislike the crowding thats part of their captivity in tanks, since (as also mentioned) one reason why lobsters claws are banded on capture is to keep them from attacking one another under the stress of close-quarter storage.

In any event, at the Festival, standing by the bubbling tanks outside the Worlds Largest Lobster Cooker, watching the fresh-caught lobsters pile over one another, wave their hobbled claws impotently, huddle in the rear corners, or scrabble frantically back from the glass as you approach, it is difficult not to sense that theyre unhappy, or frightened, even if its some rudimentary version of these feelings and, again, why does rudimentariness even enter into it? Why is a primitive, inarticulate form of suffering less urgent or uncomfortable for the person whos helping to inflict it by paying for the food it results in? Im not trying to give you a PETA-like screed hereat least I dont think so. Im trying, rather, to work out and articulate some of the troubling questions that arise amid all the laughter and saltation and community pride of the Maine Lobster Festival. The truth is that if you, the Festival attendee, permit yourself to think that lobsters can suffer and would rather not, the MLF can begin to take on aspects of something like a Roman circus or medieval torture-fest.

Does that comparison seem a bit much? If so, exactly why? Or what about this one: Is it not possible that future generations will regard our own present agribusiness and eating practices in much the same way we now view Neros entertainments or Aztec sacrifices? My own immediate reaction is that such a comparison is hysterical, extremeand yet the reason it seems extreme to me appears to be that I believe animals are less morally important than human beings;20 and when it comes to defending such a belief, even to myself, I have to acknowledge that (a) I have an obvious selfish interest in this belief, since I like to eat certain kinds of animals and want to be able to keep doing it, and (b) I have not succeeded in working out any sort of personal ethical system in which the belief is truly defensible instead of just selfishly convenient.

Given this articles venue and my own lack of culinary sophistication, Im curious about whether the reader can identify with any of these reactions and acknowledgments and discomforts. I am also concerned not to come off as shrill or preachy when what I really am is confused. Given the (possible) moral status and (very possible) physical suffering of the animals involved, what ethical convictions do gourmets evolve that allow them not just to eat but to savor and enjoy flesh-based viands (since of course refined enjoyment, rather than just ingestion, is the whole point of gastronomy)? And for those gourmets wholl have no truck with convictions or rationales and who regard stuff like the previous

paragraph as just so much pointless navel-gazing, what makes it feel okay, inside, to dismiss the whole issue out of hand? That is, is their refusal to think about any of this the product of actual thought, or is it just that they dont want to think about it? Do they ever think about their reluctance to think about it? After all, isnt being extra aware and attentive and thoughtful about ones food and its overall context part of what distinguishes a real gourmet? Or is all the gourmets extra attention and sensibility just supposed to be aesthetic, gustatory?

These last couple queries, though, while sincere, obviously involve much larger and more abstract questions about the connections (if any) between aesthetics and morality, and these questions lead straightaway into such deep and treacherous waters that its probably best to stop the public discussion right here. There are limits to what even interested persons can ask of each other.

FOOTNOTES: 1 Theres a comprehensive native apothegm: Camden by the sea, Rockland by the smell.

2 N.B. All personally connected parties have made it clear from the start that they do not want to be talked about in this article.

3 Midcoasters native term for a lobster is, in fact, bug, as in Come around on Sunday and well cook up some bugs.

4 Factoid: Lobster traps are usually baited with dead herring.

5 Of course, the common practice of dipping the lobster meat in melted butter torpedoes all these happy fat-specs, which none of the Councils promotional stuff ever mentions, any more than potatoindustry PR talks about sour cream and bacon bits.

6 In truth, theres a great deal to be said about the differences between working-class Rockland and the heavily populist flavor of its Festival versus comfortable and elitist Camden with its expensive view and shops given entirely over to $200 sweaters and great rows of Victorian homes converted to upscale B&Bs. And about these differences as two sides of the great coin that is U.S. tourism. Very little of which will be said here, except to amplify the above-mentioned paradox and to reveal your assigned

correspondents own preferences. I confess that I have never understood why so many peoples idea of a fun vacation is to don flip-flops and sunglasses and crawl through maddening traffic to loud hot crowded tourist venues in order to sample a local flavor that is by definition ruined by the presence of tourists. This may (as my Festival companions keep pointing out) all be a matter of personality and hardwired taste: The fact that I just do not like tourist venues means that Ill never understand their appeal and so am probably not the one to talk about it (the supposed appeal). But, since this note will almost surely not survive magazine-editing anyway, here goes:

As I see it, it probably really is good for the soul to be a tourist, even if its only once in a while. Not good for the soul in a refreshing or enlivening way, though, but rather in a grim, steely-eyed, lets-lookhonestly-at-the-facts-and-find-some-way-to-deal-with-them way. My personal experience has not been that traveling around the country is broadening or relaxing, or that radical changes in place and context have a salutary effect, but rather that intranational tourism is radically constricting, and humbling in the hardest wayhostile to my fantasy of being a real individual, of living somehow outside and above it all. (Coming up is the part that my companions find especially unhappy and repellent, a sure way to spoil the fun of vacation travel:) To be a mass tourist, for me, is to become a pure late-date American: alien, ignorant, greedy for something you cannot ever have, disappointed in a way you can never admit. It is to spoil, by way of sheer ontology, the very unspoiledness you are there to experience. It is to impose yourself on places that in all noneconomic ways would be better, realer, without you. It is, in lines and gridlock and transaction after transaction, to confront a dimension of yourself that is as inescapable as it is painful: As a tourist, you become economically significant but existentially loathsome, an insect on a dead thing.

7 Datum: In a good year, the U.S. industry produces around 80 million pounds of lobster, and Maine accounts for more than half that total.

8 N.B. Similar reasoning underlies the practice of whats termed debeaking broiler chickens and brood hens in modern factory farms. Maximum commercial efficiency requires that enormous poultry populations be confined in unnaturally close quarters, under which conditions many birds go crazy and peck one another to death. As a purely observational side-note, be apprised that debeaking is usually an automated process and that the chickens receive no anesthetic. Its not clear to me whether most gourmet readers know about debeaking, or about related practices like dehorning cattle in commercial feedlots, cropping swines tails in factory hog farms to keep psychotically bored neighbors from chewing them off, and so forth. It so happens that your assigned correspondent knew almost nothing about standard meat-industry operations before starting work on this article.

9 The terminal used to be somebodys house, for example, and the lost-luggage-reporting room was clearly once a pantry.

10 It turned out that one Mr. William R. Rivas-Rivas, a high-ranking PETA official out of the groups Virginia headquarters, was indeed there this year, albeit solo, working the Festivals main and side entrances on Saturday, August 2, handing out pamphlets and adhesive stickers emblazoned with Being Boiled Hurts, which is the tagline in most of PETAs published material about lobster. I learned that hed been there only later, when speaking with Mr. Rivas-Rivas on the phone. Im not sure how we missed seeing him in situ at the Festival, and I cant see much to do except apologize for the oversight although its also true that Saturday was the day of the big MLF parade through Rockland, which basic journalistic responsibility seemed to require going to (and which, with all due respect, meant that Saturday was maybe not the best day for PETA to work the Harbor Park grounds, especially if it was going to be just one person for one day, since a lot of diehard MLF partisans were off-site watching the parade (which, again with no offense intended, was in truth kind of cheesy and boring, consisting mostly of slow homemade floats and various midcoast people waving at one another, and with an extremely annoying man dressed as Blackbeard ranging up and down the length of the crowd saying Arrr over and over and brandishing a plastic sword at people, etc.; plus it rained)).

11 The short version regarding why we were back at the airport after already arriving the previous night involves lost luggage and a miscommunication about where and what the local National Car Rental franchise wasDick came out personally to the airport and got us, out of no evident motive but kindness. (He also talked nonstop the entire way, with a very distinctive speaking style that can be described only as manically laconic; the truth is that I now know more about this man than I do about some members of my own family.)

12 To elaborate by way of example: The common experience of accidentally touching a hot stove and yanking your hand back before youre even aware that anythings going on is explained by the fact that many of the processes by which we detect and avoid painful stimuli do not involve the cortex. In the case of the hand and stove, the brain is bypassed altogether; all the important neurochemical action takes place in the spine.

13 Morality-wise, lets concede that this cuts both ways. Lobster-eating is at least not abetted by the system of corporate factory farms that produces most beef, pork, and chicken. Because, if nothing else, of the way theyre marketed and packaged for sale, we eat these latter meats without having to consider that they were once conscious, sentient creatures to whom horrible things were done. (N.B. PETA distributes a certain videothe title of which is being omitted as part of the elaborate editorial

compromise by which this note appears at allin which you can see just about everything meat--related you dont want to see or think about. (N.B.2Not that PETAs any sort of font of unspun truth. Like many partisans in complex moral disputes, the PETA people are -fanatics, and a lot of their rhetoric seems simplistic and self-righteous. Personally, though, I have to say that I found this unnamed video both credible and deeply upsetting.))

14 Is it significant that lobster, fish, and chicken are our cultures words for both the animal and the meat, whereas most mammals seem to require euphemisms like beef and pork that help us separate the meat we eat from the living creature the meat once was? Is this evidence that some kind of deep unease about eating higher animals is endemic enough to show up in English usage, but that the unease diminishes as we move out of the mammalian order? (And is lamb/lamb the counterexample that sinks the whole theory, or are there special, biblico-historical reasons for that equivalence?)

15 Theres a relevant populist myth about the high-pitched whistling sound that sometimes issues from a pot of boiling lobster. The sound is really vented steam from the layer of seawater between the lobsters flesh and its carapace (this is why shedders whistle more than hard-shells), but the pop version has it that the sound is the lobsters rabbitlike death scream. Lobsters communicate via pheromones in their urine and dont have anything close to the vocal equipment for screaming, but the myths very persistentwhich might, once again, point to a low-level cultural unease about the boiling thing.

16 Interests basically means strong and legitimate preferences, which obviously require some degree of consciousness, responsiveness to stimuli, etc. See, for instance, the utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer, whose 1974 Animal Liberation is more or less the bible of the modern animal-rights movement: It would be nonsense to say that it was not in the interests of a stone to be kicked along the road by a schoolboy. A stone does not have interests because it cannot suffer. Nothing that we can do to it could possibly make any difference to its welfare. A mouse, on the other hand, does have an interest in not being kicked along the road, because it will suffer if it is.

17 This is the neurological term for special pain receptors that are (according to Jane A. Smith and Kenneth M. Boyds Lives in the Balance) sensitive to potentially damaging extremes of temperature, to mechanical forces, and to chemical substances which are released when body tissues are damaged.

18 Preference is maybe roughly synonymous with interest, but it is a better term for our purposes because its less abstractly philosophicalpreference seems more personal, and its the whole idea of a living creatures personal experience thats at issue.

19 Of course, the most common sort of counterargument here would begin by objecting that like best is really just a metaphor, and a misleadingly anthropomorphic one at that. The counterarguer would posit that the lobster seeks to maintain a certain optimal ambient temperature out of nothing but unconscious instinct (with a similar explanation for the low-light affinities about to be mentioned in the main text). The thrust of such a counterargument will be that the lobsters thrashings and clankings in the kettle express not unpreferred pain but involuntary reflexes, like your leg shooting out when the doctor hits your knee. Be advised that there are professional scientists, including many researchers who use animals in experiments, who hold to the view that nonhuman creatures have no real feelings at all, only behaviors. Be further advised that this view has a long history that goes all the way back to Descartes, although its modern support comes mostly from behaviorist psychology.

To these what-look-like-pain-are-really-only-reflexes counterarguments, however, there happen to be all sorts of scientific and pro-animal-rights countercounterarguments. And then further attempted rebuttals and redirects, and so on. Suffice to say that both the scientific and the philosophical arguments on either side of the animal-suffering issue are involved, abstruse, technical, often informed by selfinterest or ideology, and in the end so totally inconclusive that as a practical matter, in the kitchen or restaurant, it all still seems to come down to individual conscience, going with (no pun) your gut.

20 Meaning a lot less important, apparently, since the moral comparison here is not the value of one humans life vs. the value of one animals life, but rather the value of one animals life vs. the value of one humans taste for a particular kind of protein. Even the most diehard carniphile will acknowledge that its possible to live and eat well without consuming animals.

DAVID LYNCH

1. WHAT MOVIE THIS ARTICLE IS ABOUT

DAVID LYNCH's Lost Highway, written by Lynch and Barry Gifford, featuring Bill Pullman, Patricia Arquette, and Balthazar Getty. Financed by CIBY 2000, France. An October Films release. Copyright 1996, Asymmetrical Productions, Lynch's company, whose offices are near Lynch's house in the Hollywood Hills and whose logo, designed by Lynch, is a very cool graphic that looks like this:

Lost Highway is set in Los Angeles and the desertish terrain immediately inland from it. Principal shooting goes from December '95 through February '96. Lynch normally runs a closed set, with redundant security arrangements and an almost Masonic air of secrecy around his movies' productions, but I am allowed onto the Lost Highway set on 8-10 January 1996. (I This is not because of anything having to do with me or with the fact that I'm a fanatical Lynch fan from way back, though I did make my proLynch fanaticism known when the Asymmetrical people were trying to decide whether to let a writer onto the set. The fact is I was let onto Lost Highways set mostly because there's rather a lot at stake for Lynch and Asymmetrical on this movie and they probably feel like they can't afford to indulge their allergy to PR and the Media Machine quite the way they have in the past.)

2.

WHAT DAVID LYNCH IS REALLY LIKE

I HAVE NO IDEA. I rarely got closer than five feet away from him and never talked to him. You should probably know this up front. One of the minor reasons Asymmetrical Productions let me onto the set is that I don't even pretend to be a journalist and have no idea how to interview somebody, which turned out perversely to be an advantage, because Lynch emphatically didn't want to be interviewed, because when he's actually shooting a movie he's incredibly busy and preoccupied and immersed and has very little attention or brain space available for anything other than the movie. This may sound like PR bullshit, but it turns out to be true, e.g.:

The first time I lay actual eyes on the real David Lynch on the set of his movie, he's peeing on a tree. This is on 8 January in L.A.'s Griffith Park, where some of Lost Highway's exteriors and driving scenes are

being shot. He is standing in the bristly underbrush off the dirt road between the base camp's trailers and the set, peeing on a stunted pine. Mr. David Lynch, a prodigious coffee drinker, apparently pees hard and often, and neither he nor the production can afford the time it'd take to run down the base camp's long line of trailers to the trailer where the bathrooms are every time he needs to pee. So my first (and generally representative) sight of Lynch is from the back, and (understandably) from a distance. Lost Highway's cast and crew pretty much ignore Lynch's urinating in public, (though I never did see anybody else relieving themselves on the set again, Lynch really was exponentially busier than everybody else.) and they ignore it in a relaxed rather than a tense or uncomfortable way, sort of the way you'd ignore a child's alfresco peeing.

TRIVIA TIDBIT: What movie people on location sets call the trailer that houses the bathrooms: "the Honeywagon."

3. ENTERTAINMENTS DAVID LYNCH HAS CREATED AND/OR DIRECTED THAT ARE MENTIONED IN THIS ARTICLE

Eraserhead (1978), The Elephant Man (1980), Dune (1984), Blue Velvet (1986), Wild at Heart (1990), two televised seasons of Twin Peaks (1990-92), Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992), and the mercifully ablated TV show On the Air (1992).

3(A) OTHER RENAISSANCE MAN-ISH THINGS HE'S DONE

HAS DIRECTED music videos for Chris Isaak; has directed the theater teaser for Michael Jackson's lavish Dangerous video; has directed commercials for Obsession, Saint-Laurent's Opium, Alka-Seltzer, a national breast-cancer awareness campaign, (Haven't yet been able to track down clips of these spots, but the mind reels at the possibilities implicit in the conjunction of D. Lynch and radical mastectomy....) and New York City's Garbage-Collection Program. Has produced Into the Night, an album by Julee Cruise of songs cowritten by Lynch and Angelo Badalamenti, including the Twin Peaks theme and Blue Velvet's "Mysteries of Love." ("M.o.L.," only snippets of which are on BV's soundtrack, has acquired an underground reputation as one of the great make-out tunes of all time-well worth checking out.) Had for a few years a comic strip, The Angriest Dog in the World, that appeared in a handful of weekly papers, and of which Matt Greening and Bill Griffith were reportedly big fans. Has cowritten with Badalamenti (who's also cowriting the original music for Lost Highway, be apprised) Industrial Symphony #1, the 1990 video of which features Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern and Julee Cruise and the hieratic

dwarf from Twin Peaks and topless cheerleaders and a flayed deer, and which sounds pretty much like the title suggests it will. (I.e., like a blend of Brian Eno, Philip Glass, and the climactic showdown in-anautomated-factory scene from The Terminator.) Has had a bunch of gallery shows of his abstract expressionist paintings. Has codirected, with James Signorelli, 1992's ('92 having been a year of simply manic creative activity for Lynch, apparently.) Hotel Room, a feature-length collection of vignettes all set in one certain room of an NYC railroad hotel, a hoary mainstream conceit ripped off from Neil Simon and sufficiently Lynchianized in Hotel Room to be then subsequently ripoffablc from Lynch by Tarantino et posse in 1995's Four Rooms (Tarantino has made as much of a career out of ripping off Lynch as he has out of converting French New Wave film into commercially palatable U.S. paste-q.v. section). Has published Images (Hyperion, 1993), a sort of coffee-table book of movie stills, prints of Lynch's paintings, and some of Lynch's art photos (some of which are creepy and moody and sexy and cool, and some of which are just photos of spark plugs and dental equipment and seem kind of dumb). (Dentistry seems to be a new passion for Lynch, by the way-the photo on the title page of Lost Highway's script, which is of a guy with half his face normal and half unbelievably distended and ventricose and gross, was apparently plucked from a textbook on extreme dental emergencies. There's great enthusiasm for this photo around Asymmetrical Productions. and they're looking into the legalities of using it in Lost Highway's ads and posters, which if I was the guy in the photo I'd want a truly astronomical permission fee for.)

4. THIS ARTICLE'S SPECIAL FOCUS OR "ANGLE" W/N/T 'LOST HIGHWAY.' SUGGESTED (NOT ALL THAT SUBTLY) BY CERTAIN EDITORIAL PRESENCES AT 'PREMIERE' MAGAZINE

WITH THE SMASH Blue Velvet, a Palme d'or at Cannes for Wild at Heart, and then the national phenomenon of Twin Peaks' first season, David Lynch clearly established himself as the U.S.A.'s foremost commercially viable avantgarde-"offbeat" director, and for a while there it looked like he might be able to single-handedly broker a new marriage between art and commerce in U.S. movies, opening formula-frozen Hollywood to some of the eccentricity and vigor of art film. Then 1992 saw Twin Peaks' unpopular second season, the critical and commercial failure of Fire Walk With Me, and the bottomlessly horrid On the Air, which was cuthanatized by ABC after six very long-seeming weeks. This triple whammy had critics racing back to their PCs to reevaluate Lynch's whole oeuvre. The former object of a Time cover story in 1990 became the object of a withering ad hominem backlash.

So the obvious "Hollywood insider"-type question w/r/t Lost Highway is whether the movie will rehabilitate Lynch's reputation. For me, though, a more interesting question ended up being whether David Lynch really gives a shit about whether his reputation is rehabilitated or not. The impression I get from rewatching his movies and from hanging around his latest production is that he really doesn't. This attitude-like Lynch himself, like his work-seems to me to be both grandly admirable and sort of nuts.

5.A QUICK SKETCH OF LYNCH'S GENESIS AS A HEROIC AUTEUR

HOWEVER OBSESSED with fluxes in identity his movies are, Lynch has remained remarkably himself throughout his filmmaking career. You could probably argue it either way-that Lynch hasn't compromised or sold out, or that he hasn't grown all that much in twenty years of making movies-but the fact remains that Lynch has held fast to his own intensely personal vision and approach to filmmaking, and that he's made significant sacrifices in order to do so. "I mean, come on, David could make movies for anybody," says Tom Sternberg, one of Lost Highway's producers. "But David's not part of the Hollywood Process. He makes his own choices about what he wants. He's an artist." This is essentially true, though like most artists Lynch has not been without patrons. It was on the strength of Eraserhead that Mel Brooks's production company allowed Lynch to direct The Elephant Man in 1980, and that movie earned Lynch an Oscar nomination and was in turn the reason that no less an urHollywood Process figure than Dino De Laurentiis picked Lynch to make the film adaptation of Frank Herbert's Dune, offering Lynch not only big money but a development deal for future projects with De Laurentiis's production company.

1984's Dune is unquestionably the worst movie of Lynch's career, and it's pretty darn bad. In some ways it seems that Lynch was miscast as its director: Eraserhead had been one of those sell-your-own-plasmato-buy-the-film-stock masterpieces, with a tiny and largely unpaid cast and crew. Dune, on the other hand, had one of the biggest budgets in Hollywood history, and its production staff was the size of a Caribbean nation, and the movie involved lavish and cuttingedge special effects. Plus, Herbert's novel itself was incredibly long and complex and besides all the headaches of a major commercial production financed by men in Ray-Bans, Lynch also had trouble making cinematic sense of the plot, which even in the novel is convoluted to the point of pain. In short, Dune's direction called for a combination technician and administrator, and Lynch, though technically as good as anyone, is more like the type of bright child you sometimes see who's ingenious at structuring fantasies and gets totally immersed in them and will let other kids take part in them only if he retains complete imaginative control.

Watching Dune again on video, (Easy to do-it rarely leaves its spot on Blockbuster's shelf.) you can see that some of its defects are clearly Lynch's responsibility: casting the nerdy and potatofaced young Kyle MacLachlan as an epic hero and the Police's unthespian Sting as a psycho villain for example, or-worsetrying to provide plot exposition by having characters' thoughts audibilized on the soundtrack while the camera zooms in on the character making a thinking face. The overall result is a movie that's funny while it's trying to be deadly serious, which is as good a definition of a flop there is, and Dune was indeed a

huge, pretentious, incoherent flop. But a good part of the incoherence is the responsibility of the De Laurentiis producers, who cut thousands of feet of film out of Lynch's final print right before the movie's release. Even on video, it's not hard to see where these cuts were made; the movie looks gutted, unintentionally surreal.

In a strange way, though, Dune actually ended up being Lynch's Big Break as a filmmaker. The Dune that finally appeared in the theaters was by all reliable reports heartbreaking for Lynch, the kind of debacle that in myths about Innocent, Idealistic Artists in the Maw of the Hollywood Process signals the violent end of the artist's Innocence-seduced, overwhelmed, fucked over, left to take the public heat and the mogul's wrath. The experience could easily have turned Lynch into an embittered hack, doing effectsintensive gorefests for commercial studios. Or it could have sent him scurrying to the safety of academe, making obscure, plotless 16mm's for the pipe-and-beret crowd. The experience did neither. Lynch both hung in and, on some level probably, gave up. Dune convinced him of something that all the really interesting independent filmmakers-the Coen brothers, Jane Campion, Jim Jarmusch-seem to steer by. "The experience taught me a valuable lesson," he said years later. "I learned I would rather not make a film than make one where I don't have final cut." And this, in an almost Lynchianly weird way, is what led to Blue Velvet. BV's development had been one part of the deal under which Lynch had agreed to do Dune, and the latter's huge splat caused two years of rather chilly relations between Dino and Dave while the former clutched his head and the latter wrote BV's script and the De Laurentiis Entertainment Group's accountants did the postmortem on a $40 million stillbirth. Then De Laurentiis offered Lynch a deal for making BV, a very unusual sort of arrangement. For Blue Velvet, De Laurentiis offered Lynch a tiny budget and an absurdly low directorial fee, but 100 percent control over the film. It seems to me that the offer was a kind of punitive bluff on the mogul's part-a kind of be-carefulwhat-you-publiclypray-for thing. History unfortunately hasn't recorded what De Laurentiis's reaction was when Lynch jumped at the deal. It seems that Lynch's Innocent Idealism had survived Dune, and that he cared less about money and production budgets than about regaining control of the fantasy and toys. Lynch not only wrote and directed Blue Velvet, he had a huge hand in almost every aspect of the film, even coauthoring songs on the soundtrack with Badalamenti. Blue Velvet was, again, in its visual intimacy and sure touch, a distinctively homemade film (the home being, again, D. Lynch's skull), and it was a surprise hit, and it remains one of the '80s' great U.S. films. And its greatness is a direct result of Lynch's decision to stay in the Process but to rule in small personal films rather than to serve in large corporate ones. Whether you believe he's a good auteur or a bad one, his career makes it clear that he is indeed, in the literal Cahiers du Cinema sense, an auteur, willing to make the sorts of sacrifices for creative control that real auteurs have to make-choices that indicate either raging egotism or passionate dedication or a childlike desire to run the sandbox, or all three.

TRIVIA TIDBIT:

Like Jim Jarmusch's, Lynch's films are immensely popular overseas, especially in France and Japan. It's not an accident that the financing for Lost Highway is French. It's because of foreign sales that no Lynch movie has ever lost money (although I imagine Dune came close).

5(A) WHAT 'LOST HIGHWAY' IS APPARENTLY ABOUT

BILL PULLMAN is a jazz saxophonist whose relationship with his wife, a brunet Patricia Arquette, is creepy and occluded and full of unspoken tensions. They start getting incredibly disturbing videotapes in the mail that are of them sleeping or of Bill Pullman's face looking at the camera with a grotesquely horrified expression, etc.; and they're wigging out, understandably. While the creepy-video thing is under way, there are also some scenes of Bill Pullman looking very natty and East Village in all black and jamming on his tenor sax in front of a packed dance floor (only in a David Lynch movie would people dance ecstatically to abstract jazz), and some scenes of Patricia Arquette seeming restless and unhappy in a kind of narcotized, disassociated way, and generally being creepy and mysterious and making it clear that she has a kind of double life involving decadent, lounge-lizardy men. One of the creepier scenes in the movie's first act takes place at a decadent Hollywood party held by one of Atquette's mysterious lizardy friends. At the party Pullman is approached by somebody the script identifies only as "The Mystery Man" (Robert Blake), who claims not only that he's been in Bill Pullman and Patricia Arquette's house but that he's actually there at their house right now.

But then so driving home from the party, Bill Pullman criticizes Patricia Arquette's friends but doesn't say anything specific about the creepy and metaphysically impossible conversation with one guy in two places he just had, which I think is supposed to reinforce our impression that Bill Pullman and Patricia Arquette are not exactly confiding intimately in each other at this stage in their marriage. This impression is further reinforced by a creepy sex scene in which Bill Pullman has frantic wheezing sex with a Patricia Arquette who just lies there inert and all but looking at her watch (A sex scene that is creepy partly because it's exactly what I imagine having sex with Patricia Arquette would be like).

But then so the thrust of Lost Highway's first act is that the final mysterious video shows Bill Pullman standing over the mutilated corpse of Patricia Arquette-we see it only on the video-and he's arrested and convicted and put on death row. Then there's a scene in which Bill Pullman's head turns into Balthazar Getty's head. I won't even try to describe the scene except to say that it's ghastly and riveting. The administration of the prison is understandably nonplussed when they see Balthazar Getty in Bill

Pullman's cell instead of Bill Pullman. Balthazar Getty is no help in explaining how he got there, because he's got a huge hematoma on his forehead and his eyes are wobbling around and he's basically in the sort of dazed state you can imagine somebody being in when somebody else's head has just changed painfully into his own head. No one's ever escaped from this prison's death row before, apparently, and the penal authorities and cops, being unable to figure out how Bill Pullman escaped and getting little more than dazed winces from Balthazar Getty, decide (in a move whose judicial realism may be a bit shaky) simply to let Balthazar Getty go home.

It turns out that Balthazar Getty is an incredibly gifted professional mechanic who's been sorely missed at the auto shop where he works-his mother has apparently told Balthazar Getty's employer, who's played by Richard Pryor, that Balthazar Getty's absence has been due to a "fever." Balthazar Getty has a loyal clientele at Richard Pryor's auto shop, one of whom, Mr. Eddy, played by Robert Loggia, is a menacing crime boss-type figure with a thuggish entourage and a black Mercedes 6.9, and who has esoteric troubles that hell trust only Balthazar Getty to diagnose and fix. Robert Loggia clearly has a history with Balthazar Getty and treats Balthazar Getty (11 I know Balthazar Getty's name is getting repeated an awful lot, but I think it's one of the most gorgeous and absurd real-person names I've ever heard, and I found myself on the set taking all kinds of notes about Balthazar Getty that weren't really necessary or useful (since the actual Balthazar Getty turned out to be uninteresting and puerile and narcissistic as only an oil heir who's a movie star just out of puberty can be), purely for the pleasure of repeating his name as often as possible) with a creepy blend of avuncular affection and patronizing ferocity. When Robert Loggia pulls into Richard Pryor's auto shop with his troubled Mercedes 6.9, one day, in the car, alongside his thugs, is an unbelievably gorgeous gun moll-type girl, played by Patricia Arquette and clearly recognizable as same, i.e., Bill Pullman's wife, except now she's a platinum blond. (If you're thinking Vertigo here, you're not far astray, though Lynch has a track record of making allusions and homages to Hitchcock-e.g. BV's first shot of Kyle MacLachian spying on Isabella Rossellini through the louvered slots of her closet door is identical in every technical particular to the first shot of Anthony Perkins spying on Vivian Leigb's ablutions in Psycho-that are more like intertextual touchstones than outright allusions, and anyway are always taken in weird and creepy and uniquely Lynchian directions.)

And but so when Balthazar Getty's new blue-collar incarnation of Bill Pullman and Patricia Arquette's apparent blond incarnation of Bill Pullman's wife make eye contact, sparks are generated on a scale that gives the hackneyed I-feel-l-know-you-from-somewhere component of erotic attraction new layers of creepy literality.

It's probably better not to give away much of Lost Highway's final act, though you probably ought to be apprised: that the blond Patricia Arquette's intentions toward Balthazar Getty turn out to be less than honorable; that Balthazar Getty's ghastly forehead hematoma all but completely heals up; that Bill

Pullman does reappear in the movie; that the brunet Patricia Arquette also reappears but not in the (so to speak) flesh; that both the blond and the brunet P. Arquette turn out to be involved (via lizardy friends) in the world of porn, as in hardcore, an involvement whose video fruits are shown (at least in the rough cut) in NC-17-worthy detail; and that Lost Highway's ending is by no means an "upbeat" or "feel-good" ending. Also that Robert Blake, while a good deal more restrained than Dennis Hopper was in Blue Velvet, is at least as riveting and creepy and unforgettable as Hopper's Frank Booth was, and is pretty clearly the devil, or at least somebody's very troubling idea of the devil, a kind of pure floating spirit of malevolence like Twin Peaks' Bob/Leland/Scary Owl.

At this point it's probably impossible to tell whether Lost Highway is going to be a Dune-level turkey or a Blue Velvet-caliber masterpiece or something in between or what. The one thing I feel I can say with total confidence is that the movie will be...Lynchian.

6. WHAT 'LYNCHIAN' MEANS AND WHY IT'S IMPORTANT

AN ACADEMIC DEFINITION of Lynchian might be that the term "refers to a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former's perpetual containment within the latter." But like postmodern or pornographic, Lynchian is one of those Porter Stewart-type words that's ultimately definable only ostensively-i.e., we know it when we see it. Ted Bundy wasn't particularly Lynchian, but good old Jeffrey Dahmer, with his victims' various anatomies neatly separated and stored in his fridge alongside his chocolate milk and Shedd Spread, was thoroughgoingly Lynchian. A recent homicide in Boston, in which the deacon of a South Shore church reportedly gave chase to a vehicle that bad cut him off, forced the car off the road, and shot the driver with a highpowered crossbow, was borderline Lynchian. A Rotary luncheon where everybody's got a comb-over and a polyester sport coat and is eating bland Rotarian chicken and exchanging Republican platitudes with heartfelt sincerity and yet all are either amputees or neurologically damaged or both would be more Lynchian than not. A hideously bloody street fight over an insult would be a Lynchian street fight if and only if the insultee punctuates every kick and blow with an injunction not to say fucking anything if you can't say something fucking nice.

For me, Lynch's movies' deconstruction of this weird irony of the banal has affected the way I see and organize the world. I've noted since 1986 (when Blue Velvet was released) that a good 65 percent of the people in metropolitan bus terminals between the hours of midnight and 6 A.M. tend to qualify as

Lynchian figures-grotesque, enfeebled, flamboyantly unappealing, freighted with a woe out of all proportion to evident circumstances ... a class of public-place humans I've privately classed, via Lynch, as "insistently fucked up." Or, e.g. we've all seen people assume sudden and grotesque facial expressionslike when receiving shocking news, or biting into something that turns out to be foul, or around small kids for no particular reason other than to be weird-but I've determined that a sudden grotesque facial expression won't qualify as a really Lynchian facial expression unless the expression is held for several moments longer than the circumstances could even possibly warrant, until it starts to signify about seventeen different thin sat once.

TRIVIA TIDBIT: When Eraserhead was a surprise hit at festivals and got a distributor, David Lynch rewrote the cast and crew's contracts so they would all get a share of the money, which they still do, now, every fiscal quarter. Lynch's AD and PA and everything else on Eraserhead was Catherine E. Coulson, who was later Log Lady on Twin Peaks. Plus, Coulson's son, Thomas, played the little boy who brings Henry's ablated head into the pencil factory. Lynch's loyalty to actors and his homemade, co-op-style productions make his oeuvre a pomo anthill of interfilm connections.

7. LYNCHIANISM'S AMBIT IN CONTEMPORARY MOVIES

IN 1995, PBS ran a lavish ten-part documentary called American Cinema whose final episode was devoted to "The Edge of Hollywood" and the increasing influence of young independent filmmakers-the Coens, Carl Franklin, Q. Tarantino, et al. It was not just unfair, but bizarre, that David Lynch's name was never once mentioned in the episode, because his influence is all over these directors like white on rice. The Band-Aid on the neck of Pulp Fiction's Marcellus Wallace-unexplained, visually incongruous, and featured prominently in three separate setups-is textbook Lynch. As are the long, self-consciously mundane dialogues on foot massages, pork bellies, TV pilots, etc. that punctuate Pulp Fiction's violence, a violence whose creepy-comic stylization is also Lynchian. The peculiar narrative tone of Tarantino's films-the thing that makes them seem at once strident and obscure, not-quite-clear in a haunting way-is Lynch's; Lynch invented this tone. It seems to me fair to say that the commercial Hollywood phenomenon that is Mr. Quentin Tarantino would not exist without David Lynch as a touchstone, a set of allusive codes and contexts in the viewers midbrain. In a way, what Tarantino has done with the French New Wave and with Lynch is what Pat Boone did with rhythm and blues: He's found (ingeniously) a way to take what is ragged and distinctive and menacing about their work and homogenize it, churn it until it's smooth and cool and hygienic enough for mass consumption. Reservoir Dogs, for example, with its comically banal lunch chatter, creepily otiose code names, and intrusive soundtrack of campy pop from decades past, is a Lynch movie made commercial, i.e., fast, linear, and with what was idiosyncratically surreal now made fashionably (i.e., "hiply") surreal.

In Carl Franklin's powerful One False Move, his crucial decision to focus only on the faces of witnesses during violent scenes seems resoundingly Lynchian. So does the relentless, noir-parodic use of chiaroscuro lighting used in the Coens' Blood Simple and in all Jim Jarmusch's films ... especially Jarmusch's 1984 Stranger Than Paradise, which, in terms of cinematography, blighted setting, wet-fuse pace, heavy dissolves between scenes, and a Bressonian style of acting that is at once manic and wooden, all but echoes Lynch's early work. One homage you've probably seen is Gus Van Sant's use of surreal dream scenes to develop River Phoenix's character in My Own Private Idaho. In the movie, the German john's creepy, expressionistic lip-sync number, using a handheld lamp as a microphone, comes off as a more or less explicit reference to Dean Stockwell's unforgettable lamp-sync scene in Blue Velvet. Or consider the granddaddy of inyour-ribs Blue Velvet references: the scene in Reservoir Dogs in which Michael Madsen, dancing to a cheesy '70s Top 40 tune, cuts off a hostage's ear-I mean, think about it.

None of this is to say that Lynch himself doesn't owe debts-to Hitchcock, to Cassavetes, to Robert Bresson and Maya Deren and Robert Wiene. But it is to say that Lynch has in many ways cleared and made arable the contemporary "anti"-Hollywood territory that Tarantino et al. are cash-cropping right now.

8. RE: THE ISSUE OF WHETHER AND IN WHAT WAY DAVID LYNCH'S MOVIES ARE 'SICK'

PAULINE KAEL has a famous epigram to her New Yorker review of BV. She quotes somebody she left the theater behind as saying to a friend, "Maybe I'm sick, but I want to see that again." And Lynch's movies are indeed-in all sorts of ways, some more interesting than others-sick. Some of them are brilliant and unforgettable; others are almost unbelievably jejune and crude and incoherent and bad. It's no wonder that Lynch's critical reputation over the last decade has looked like an EKG: It's hard to tell whether the director's a genius or an idiot. This, for me, is part of his fascination.

If the word sick seems excessive, substitute the word creepy. Lynch's movies are inarguably creepy, and a big part of their creepiness is that they seem so personal. A kind and simple way to put it is that Lynch's movies seem to be expressions of certain anxious, obsessive, fetishistic, oedipally arrested, borderlinish parts of the director's psyche, expressions presented with little inhibition or semiotic layering, i.e., presented with something like a child's ingenuous (and sociopathic) lack of selfconsciousness. It's the psychic intimacy of the work that makes it hard to sort out what you feel about one of David Lynch's movies and what you feel about David Lynch. The ad hominem impression one tends to carry away from a Blue Velvet or a Fire Walk With Me is that they're really powerful movies,

but David Lynch is the sort of person you really hope you don't get stuck next to on a long flight or in line at the DMV or something. In other words, a creepy person.

Depending on whom you talk to, Lynch's creepiness is either enhanced or diluted by the odd distance that seems to separate his movies from the audience. Lynch's movies tend to be both extremely personal and extremely remote. The absence of linearity and narrative logic, the heavy multivalence of the symbolism, the glazed opacity of the characters' faces, the weird, ponderous quality of the dialogue, the regular deployment of grotesques as figurants, the precise, painterly way the scenes are staged and lit, and the overlush, possibly voyeuristic way that violence, deviance, and general hideousness are depicted-these all give Lynch's movies a cool, detached quality, one that some cineasts view as more like cold and clinical.

Here's something that's unsettling but true: Lynch's best movies are also the ones that strike people as his sickest. I think this is because his best movies, however surreal, tend to be anchored by welldeveloped main characters-Blue Velvet's Jeffrey Beaumont, Fire Walk With Me's Laura, The Elephant Man's Merrick and Treves. When characters are sufficiently developed and human to evoke our empathy, it tends to break down the carapace of distance and detachment in Lynch, and at the same time it makes the movies creepier-we're way more easily disturbed when a disturbing movie has characters in whom we can see parts of ourselves. For example, there's way more general ickiness in Wild at Heart than there is in Blue Velvet, and yet Blue Velvet is a far creepier/sicker film, simply because Jeffrey Beaumont is a sufficiently 3-D character for us to feet about/for/with. Since the really disturbing stuff in Blue Velvet isn't about Frank Booth or anything Jeffrey discovers about Lumberton, but about the fact that a part of Jeffrey gets off on voyeurism and primal violence and degeneracy, and since Lynch carefully sets up his film both so that we feet a/f/w Jeffrey and so that we find some parts of the sadism and degeneracy he witnesses compelling and somehow erotic, it's little wonder that we (I?) find Blue Velvet "sick"-nothing sickens me like seeing onscreen some of the very parts of myself I've gone to the good old movies to try to forget about.

9. ONE OF THE RELATIVELY PICAYUNE 'LOST HIGHWAY' SCENES I GOT TO BE ON THE SET OF

GIVEN HIS movies' penchant for creepy small towns, Los Angeles might seem an unlikely place for Lynch to set Lost Highway. Los Angeles in January, though, turns out to be plenty Lynchian in its own right. Surreal-banal interpenetrations are every place you look. The cab from LAX has a machine attached to the meter so you can pay the fare by major credit card. Or see my hotel lobby, which is filled with beautiful Steinway piano music, except when you go over to put a buck in the piano player's snifter or whatever it turns out there's nobody playing, the piano's playing itself, but it's not a player piano, it's a

regular Steinway with a weird computerized box attached to the underside of its keyboard; the piano plays 24 hours a day and never once repeats a song. My hotel's in what's either West Hollywood or the downscale part of Beverly Hills; two clerks at the registration desk start arguing the point when I ask where exactly in L.A. we are. They go on for a Lynchianly long time.