Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Missing Economics of Influential Economist John Kenneth Galbraith

Încărcat de

Anish S.MenonTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Missing Economics of Influential Economist John Kenneth Galbraith

Încărcat de

Anish S.MenonDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Missing-in-Action Economics of John Kenneth Galbraith

J. Bradford DeLong Professor of Economics, U.C. Berkeley Research Associate, NBER brad.delong@gmail.com December 2006

John Kenneth Galbraith was the most politically-influential American economist in the twentieth century. He gave more advice to more presidents and senators than should have been possible with three lives. The pieces of advice that we remember best are those that went counter to that time's "conventional wisdom," a phrase that Galbraith coined: that strategic bombing did not win World War II; that Vietnam was a strategically-unimportant quagmire where we were likely to do more harm than good; that claims for the macroeconomic "fine tuning" of the economy were likely to blow up in your face; that the capacity of businessmen to delude themselves was nearly infinite. Galbraith's politics have been in retreat for a generation now. John Kenneth Galbraith saw America as a would-be social democracy that has lost its way. If only Americans were to cease to credit the delusions and self-serving declarations of the right, he thought, then it would become crystal clear that a bigger government doing more things would make America a much better place. Galbraith's political views have been losing relative influence for a generation now, for both good and bad intellectual reasons and for largely bad sociological reasons as well. Nobody today likes to hear about the importance of Big Government, Big Labor (which barely exists), and Big Bureaucracy. On the bad-intellectual-reason side,

big business prefers to redefine itself as entrepreneurial and self-reliant CEOs bending reality to their will, rather than as sophisticated organs of relatively large-scale planning embedded in an imperfectly-competitive economy. And nobody today wants to claim that there is a Big Enough Labor to exercise any effective power at a scale sufficiently large to be countervailing. On the good-intellectual-reason side, Galbraith lacked a comprehensive and easily-graspable theory of government failure. Declarations that markets are producing substantial failures call forth the question, "compared to what?" And until American liberals have a good, comprehensive, and easily-grasped theory of governmental failure and success, competence and incompetence, I believe that they will continue to find themselves in relative retreat. Richard Parker has a powerful sociological explanation for the relative eclipse of Galbraith's politics: a loss of nerve on the part of America's Democratic Party establishment. Too many Democratic intellectuals and politicians drink cocktails at Martha's Vineyard and not enough spend time on the shop floor learning what issues are important to those sweeping-up or on the assembly line or manning the convenience store cash register from midnight to six--and so the mass base of the Democratic Party withers. Without a mass base, Democratic politicians listen too much to their relatively rich contributors, and turn into Eisenhower Republicans--people like me. But I am here to talk not about Galbraith's political activities, his politics, or his policy advice: I am here to talk about John Kenneth Galbraith's economics--an economics that, I have said before, ought to have made him one of the most if not the most influential American economist of the twentieth century. And Galbraith's economic views have undergone an even more distressing eclipse. Among economists--my own tribe, the tribe of economic historians, an exception--the seventy-year-olds have read Galbraith and think he is very important; the fifty-year-olds have read Galbraith and know that the seventy-year-olds think he is important, but are not sure why; and the thirty-year-olds have not read Galbraith.

One part of the story is one of blindness on the part of an academic establishment descended from Paul Samuelson's Foundations of Economic Analysis. Paul Krugman made this point in a different context in his paper on "The Fall and Rise of Development Economics": if one values formal modelling, but is not very good at it, then the range of ideas that you can seriously consider will be small and limited to those that your relativelyfeeble modelling skills can grasp. Economists over the past generations have not yet been that good at formal modelling. And so insights that find institutional and narrative expression are stripped out of the discourse when it moves to the model-building stage. Harry Johnson, in his superb but not-entirely-fair Ely Lecture criticizing Milton Friedman's Monetarists, said that in order to carry out an intellectual revolution in economics you need to propound a doctrine that has three properties: 1. It can be summarized in a sentence. 2. It must provide the young with an excuse for not reading their elders. 3. It must provide clear signposts telling the young what they can do to contribute to the ongoing revolution. John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman both propounded such doctrines. They said, respectively, that "aggregate demand determined supply" and that "inflation was always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon"; they dismissed their predecessors as obsolete; they set hundreds of young to the task of estimating consumption, investment, and money demand functions. John Kenneth Galbraith propounded no such easily-summarizable doctrine. The closest we can get is: "the world is complicated, and the conventional wisdom that is this age's self-image and the right-wing ideologues are both terribly wrong." For Galbraith, there is no one market failure to serve as serpent in the Eden of perfect competition. He starts from the ground up--what are the major economic institutions, and how do they interact? You could not tell somebody how to follow in Galbraith's

footsteps. The only advice you could give would be useless: Be supremely witty. Write very well. Read very widely Know a great deal of institutional detail. Galbraith provided critiques of old theories which required that you have read and understood them--not a new theory that excused you dismissing everything earlier as irrelevant. And there were no signposts pointing down the path to become a Galbraithian. The result? In academic economics today, we are nearly all Paul Samuelson's children. Many of us are John Maynard Keynes's children. Bob Solow and Milton Friedman and Bob Lucas and Jim Tobin have many descendants. But Galbraithians are few on the ground. Would economics as a discipline be stronger if the fifty-year-olds and the thirtyyear-olds had the appreciation of Galbraith that their seventy-year-old elders do? In my view, almost surely. Will economic fashion turn and economists appreciate Galbraith once more? For that to happen, somebody would have to turn their hand to mathing-up chapters of The Affluent Society and The New Industrial State and publishing them in journals. That's too high-stakes a bet for assistant professors to make, and those with tenure already have their own research projects. This is a shame. Professors teaching the United States since World War II can still do no better than to assign his books The Affluent Society and The New Industrial State to teach students what the American economy that so dominated the world in the middle of the twentieth century looked like--and what a post-New Deal liberal thought should be done to make it work better. Anyone wanting to learn about the start of the Great Depression or about the functioning of financial markets in a time of irrational exuberance should still start with Galbraith's The Great Crash: there will never be another history of the stock market bubble of 1929 that is as worth reading. During World War II he played a key administrative role in squaring the circle that was pushing production far above economists' measures of potential output while not allowing runaway inflation to undermine the legitimacy of economic mobilization for World War II at the Office of Price Administration. These are the insights that drop away when we move to formal models.

Galbraith's work as an economist was a scattered but comprehensive attempt to think through the consequences of the replacement of an America of small farms and workshops by one of large factories and superstores. Just how influential could advertising be in shaping demand? In a world of passive shareholders, autonomous managers and engineers, and firm decisions that emerged out of internal bureaucratic contests, just what were the objectives that big firms acted as if they were pursuing? How did competition work when its principle dimension was not price but instead quality and perhaps advertising? How did the limits of thoughts permitted in polite discourse--the "conventional wisdom"--allow the system to hold itself together while constraining its flexibility? And if economists' standard vision of competition was in fact as weak as Galbraith believed it to be, why was the mid-twentieth-century American economy so efficient compared to every single other nation? The conventional wisdom among American economists and in American economics today tends to endorse claims that the most efficient economy is one in which the gales of perfect competition scour the land clean. In Galbraith's view, these arguments were nonsense. Even when undertaken not by one but many firms, modern industrial and post-industrial production is a very large-scale process; large-scale requires planning; and planning requires a certain stability, which means that the gales of large swings in market prices and in quantities demanded have to be contained or at least managed. As Marty Weitzman formalized a generation ago, relatively centralized planning have the advantage when the costs of failing to coordinate quantities in the right proportions are high, and decentralized markets have the advantage when the costs of failing to respond to shocks to users' value are high. So, then, what would a Galbraith-school or a Galbrath-influenced-school or a Galbraithian economics for the twenty-first century look like? What would be the research program that could produce useful insights about the economy in a distinctively Galbraithian vein? A first thread would pick up Galbraith's argument that we are an affluent society, an argument that he made in The Affluent Society. Adam Smith's

Britain was poor. Most people most of the time had relatively simple demands: enough food not to be hungry, enough clothing not to be cold, enough shelter not to be wet. Today we--at least those of us here--have more complicated and subtle market demands: enough comforts not to be uncomfortable, enough entertainment not to be bored, and enough status markers not to feel small. This change is one of the most glorious things about our economy and technology. As George Stigler liked to say, it is the very essence of economic progress to turn conveniences into necessities, luxuries into conveniences, and to invent new and previously unheard-of luxuries. But while the nature of the things demanded in relatively poor societies is relatively obvious, the nature of things demanded in affluent societies is not. The psychological-sociological-economic process by which we decide what our wants are is something that is desperately important in understanding our economy. It is something that businesses that spend a fortune on non-informative advertising are desperately eager to influence and guide. It is something we do not understand very well. Galbraith did not have a theory of the shaping of tastes and the formation of demand. He has insights--the insight that demand for public national parks was likely to be too low and demand for SUVs too high because a great deal of money was spent drawing symbolic links between driving an SUV and being happy, while there was no countervailing costly drawingof-symbolic-links between having national parks and being happy. Galbraith's observations called forth a vociferous critique. I have always liked Milton Friedman's version. He viewed Galbraith as the modern-day equivalent of an early nineteenth century anti-market radical Tory: "Many reformers -- Galbraith is not alone in this -- have as their basic objection to a free market that it frustrates them in achieving their reforms, because it enables people to have what they want, not what the reformers want. Hence every reformer has a strong tendency to be averse to a free market." A second thread would pick up on Galbraith's sociology of organizations: the ideas that form a cloud around Galbraith's word "technostructure." If Ronald Coase were here, he would agree that the existence of so many

very large firms spanning so many industries indicates that there are truly powerful advantages over a large scale to coordination through authority and command and bureaucracy rather than through market exchange. But he would be at sea with respect to what businesses that have substantial freedom not to obey market forces actually do. What do they do? Galbraith pointed out incentives for organizational growth, incentives to take steps to maintain market stability, incentives toward technological rationality. We today would add an incentive to pay the CEO an absolute fortune as the winner of some complicated tournament--and we can observe that the current patterns in topmanagement compensation are a powerful argument that the pressures to maximize shareholder value are not all that great. But we have advanced little beyond Galbraith's insights of the 1960s in our understanding of how market forces constrain and fail to constrain large business organizations, and why they do what they do with what relative freedom of action that they have. The third thread would pick up on the relationship between technological development and large business enterprise. I think it was Paul Samuelson who I first heard say, "It takes a heap of Harberger triangles to make up for one Bell Labs." One of the things that AT&T bought with its effective monopoly over telephones before 1985 was a quiet, orderly, organized life. Another thing that it bought was a lot of fundamental and applied research. What does the balance sheet say about this? The questions asked by Galbraith's economics are now, I think, lowhanging fruit. I look forward to seeing lots of interesting and productive work on them over the next two decades.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Lombard Street: A Description of the Money MarketDe la EverandLombard Street: A Description of the Money MarketEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (3)

- The Rising Gulf: The New Ambitions of the Gulf MonarchiesDe la EverandThe Rising Gulf: The New Ambitions of the Gulf MonarchiesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Politics of Inflation: A Comparative AnalysisDe la EverandThe Politics of Inflation: A Comparative AnalysisRichard MedleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Normative Economics: An Introduction to Microeconomic Theory and Radical CritiquesDe la EverandNormative Economics: An Introduction to Microeconomic Theory and Radical CritiquesÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Did Economists Get It So WrongDocument10 paginiHow Did Economists Get It So WrongCarlo TrobiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Great Leap Forward: Heterodox Economic Policy for the 21st CenturyDe la EverandA Great Leap Forward: Heterodox Economic Policy for the 21st CenturyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The New Masters of Capital: American Bond Rating Agencies and the Politics of CreditworthinessDe la EverandThe New Masters of Capital: American Bond Rating Agencies and the Politics of CreditworthinessEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (3)

- The European Economy since 1945: Coordinated Capitalism and BeyondDe la EverandThe European Economy since 1945: Coordinated Capitalism and BeyondEvaluare: 1.5 din 5 stele1.5/5 (2)

- The Architecture of Markets: An Economic Sociology of Twenty-First-Century Capitalist SocietiesDe la EverandThe Architecture of Markets: An Economic Sociology of Twenty-First-Century Capitalist SocietiesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Austerity: When is it a mistake and when is it necessary?De la EverandAusterity: When is it a mistake and when is it necessary?Încă nu există evaluări

- England's Cross of Gold: Keynes, Churchill, and the Governance of Economic BeliefsDe la EverandEngland's Cross of Gold: Keynes, Churchill, and the Governance of Economic BeliefsÎncă nu există evaluări

- (FreeCourseWeb - Com) ForeignAffairs01.022020 PDFDocument208 pagini(FreeCourseWeb - Com) ForeignAffairs01.022020 PDFTiosavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foreign Direct Investment in Brazil: Post-Crisis Economic Development in Emerging MarketsDe la EverandForeign Direct Investment in Brazil: Post-Crisis Economic Development in Emerging MarketsEvaluare: 1 din 5 stele1/5 (1)

- (Robert Lekachman (Eds.) ) Keynes' General Theory PDFDocument355 pagini(Robert Lekachman (Eds.) ) Keynes' General Theory PDFAlvaro Andrés Perdomo100% (1)

- Economics: Private and Public ChoiceDe la EverandEconomics: Private and Public ChoiceEvaluare: 2.5 din 5 stele2.5/5 (12)

- Marc Lavoie History and Methods of Post Keynesian Economics 184458Document34 paginiMarc Lavoie History and Methods of Post Keynesian Economics 184458José Ignacio Fuentes PeñaililloÎncă nu există evaluări

- In the Long Run We Are All Dead: Keynesianism, Political Economy, and RevolutionDe la EverandIn the Long Run We Are All Dead: Keynesianism, Political Economy, and RevolutionEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (4)

- Regulating Capital: Setting Standards for the International Financial SystemDe la EverandRegulating Capital: Setting Standards for the International Financial SystemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Across the Great Divide: New Perspectives on the Financial CrisisDe la EverandAcross the Great Divide: New Perspectives on the Financial CrisisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Keynes and CapitalismDocument28 paginiKeynes and CapitalismKris TianÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hesitant Hand: Taming Self-Interest in the History of Economic IdeasDe la EverandThe Hesitant Hand: Taming Self-Interest in the History of Economic IdeasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Financial Fine Print: Uncovering a Company's True ValueDe la EverandFinancial Fine Print: Uncovering a Company's True ValueEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (3)

- The Visionary Realism of German Economics: From the Thirty Years' War to the Cold WarDe la EverandThe Visionary Realism of German Economics: From the Thirty Years' War to the Cold WarÎncă nu există evaluări

- (New Thinking in Political Economy Series) Richard M. Salsman - The Political Economy of Public Debt - Three Centuries of Theory and Evidence-Edward Elgar Pub (2017) PDFDocument331 pagini(New Thinking in Political Economy Series) Richard M. Salsman - The Political Economy of Public Debt - Three Centuries of Theory and Evidence-Edward Elgar Pub (2017) PDFioannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quantitative Easing: The Great Central Bank ExperimentDe la EverandQuantitative Easing: The Great Central Bank ExperimentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mad money: with an introduction by Benjamin J. CohenDe la EverandMad money: with an introduction by Benjamin J. CohenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essentials of Economic Theory: As Applied to Modern Problems of Industry and Public PolicyDe la EverandEssentials of Economic Theory: As Applied to Modern Problems of Industry and Public PolicyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emerging Market Economies and Financial Globalization: Argentina, Brazil, China, India and South KoreaDe la EverandEmerging Market Economies and Financial Globalization: Argentina, Brazil, China, India and South KoreaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swans, Swine, and Swindlers: Coping with the Growing Threat of Mega-Crises and Mega-MessesDe la EverandSwans, Swine, and Swindlers: Coping with the Growing Threat of Mega-Crises and Mega-MessesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Political Economy of Industrial Strategy in the UK: From Productivity Problems to Development DilemmasDe la EverandThe Political Economy of Industrial Strategy in the UK: From Productivity Problems to Development DilemmasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World by Adam Tooze | Conversation StartersDe la EverandCrashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World by Adam Tooze | Conversation StartersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Macromodeling Debt and Twin Deficits: Presenting the Instruments to Reduce ThemDe la EverandMacromodeling Debt and Twin Deficits: Presenting the Instruments to Reduce ThemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Taming Japan's Deflation: The Debate over Unconventional Monetary PolicyDe la EverandTaming Japan's Deflation: The Debate over Unconventional Monetary PolicyÎncă nu există evaluări

- European Investment Bank Activity Report 2020: Crisis SolutionDe la EverandEuropean Investment Bank Activity Report 2020: Crisis SolutionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fateful Decisions: Choices That Will Shape China's FutureDe la EverandFateful Decisions: Choices That Will Shape China's FutureÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grant's Interest Rate Observer X-Mas IssueDocument27 paginiGrant's Interest Rate Observer X-Mas IssueCanadianValueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Backhouse & Tribe 2018 The History of EconomicsDocument33 paginiBackhouse & Tribe 2018 The History of EconomicsxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Between Left and Right: The 2009 Bundestag Elections and the Transformation of the German Party SystemDe la EverandBetween Left and Right: The 2009 Bundestag Elections and the Transformation of the German Party SystemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reducing Inflation: Motivation and StrategyDe la EverandReducing Inflation: Motivation and StrategyChristina D. RomerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kelton, Deficit Myth, Introduction For PublicityDocument14 paginiKelton, Deficit Myth, Introduction For PublicityOnPointRadio100% (1)

- Rostow's stages vs structural change models vs dependence theoryDocument1 paginăRostow's stages vs structural change models vs dependence theoryMaureen LeonidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Taxation of Income from Capital: A Comparative Study of the United States, the United Kingdom, Sweden and West GermanyDe la EverandThe Taxation of Income from Capital: A Comparative Study of the United States, the United Kingdom, Sweden and West GermanyEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Information Assimilation Among Indian Stocks Impact of Turnover and Firm SizeDocument24 paginiInformation Assimilation Among Indian Stocks Impact of Turnover and Firm SizeAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lyons R K (2001) The Microstructure Approach To Exchange Rates, London MIT Press (Sup)Document63 paginiLyons R K (2001) The Microstructure Approach To Exchange Rates, London MIT Press (Sup)Michael William TreherneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ambedkar - Universal As The Sun - NavayanaDocument3 paginiAmbedkar - Universal As The Sun - NavayanaAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rent ReceiptDocument1 paginăRent ReceiptSuhrab Khan JamaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Institutes of Management Bill, 2015Document30 paginiInstitutes of Management Bill, 2015Latest Laws TeamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lipper CategoriesDocument7 paginiLipper CategoriesAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behavioural Accounting and FinanceDocument22 paginiBehavioural Accounting and FinanceAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civilization Book ReviewDocument10 paginiCivilization Book ReviewAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sandy Lai HKU PaperDocument49 paginiSandy Lai HKU PaperAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is Your Fund Manager Active EnoughDocument3 paginiIs Your Fund Manager Active EnoughAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ferson Schadt MethodologyDocument38 paginiFerson Schadt MethodologyAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Policy Term Paper Anish FinalDocument26 paginiPolicy Term Paper Anish FinalAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Problematic of Social Representation - Who Must Write On Ambedkar, Dalit History and Politics - InclusiveDocument6 paginiThe Problematic of Social Representation - Who Must Write On Ambedkar, Dalit History and Politics - InclusiveAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Corporate Finance - CEO Age & Acquisition PropensityDocument8 paginiCorporate Finance - CEO Age & Acquisition PropensityAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Corporate Finance ComprehensiveDocument10 paginiCorporate Finance ComprehensiveAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Psychology Term PaperDocument8 paginiSocial Psychology Term PaperAnish S.Menon100% (1)

- Microinsurance Term Paper RevisedDocument25 paginiMicroinsurance Term Paper RevisedAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary Statistics FinalDocument63 paginiSummary Statistics FinalAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Corporate Finance ComprehensiveDocument10 paginiCorporate Finance ComprehensiveAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- ICSI Bangalore Chapter Student Conference Milaap 2012Document114 paginiICSI Bangalore Chapter Student Conference Milaap 2012Anish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Was He?: Anish S. Menon MS Scholar Department of Management Studies IIT Madras The EndDocument7 paginiWas He?: Anish S. Menon MS Scholar Department of Management Studies IIT Madras The EndAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Financial EconometricsDocument7 paginiFinancial EconometricsAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Milaap 2014 - e SouvenirDocument106 paginiMilaap 2014 - e SouvenirAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Milaap 2013 E-SouvenirDocument106 paginiMilaap 2013 E-SouvenirAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accounting Theory and Empirical Research - Research ProposalDocument1 paginăAccounting Theory and Empirical Research - Research ProposalAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vedasaarsiva StotramDocument4 paginiVedasaarsiva Stotrammishra012Încă nu există evaluări

- Milaap 2014 - e SouvenirDocument106 paginiMilaap 2014 - e SouvenirAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Banking Term Paper PDFDocument34 paginiBanking Term Paper PDFAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Egg BiriyaniDocument9 paginiEgg BiriyaniAnish S.MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bad DayDocument3 paginiBad DayLink YouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Year Project (Product Recommendation)Document33 paginiFinal Year Project (Product Recommendation)Anurag ChakrabortyÎncă nu există evaluări

- CDI-AOS-CX 10.4 Switching Portfolio Launch - Lab V4.01Document152 paginiCDI-AOS-CX 10.4 Switching Portfolio Launch - Lab V4.01Gilles DellaccioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Laryngeal Diseases: Laryngitis, Vocal Cord Nodules / Polyps, Carcinoma LarynxDocument52 paginiLaryngeal Diseases: Laryngitis, Vocal Cord Nodules / Polyps, Carcinoma LarynxjialeongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Equilibruim of Forces and How Three Forces Meet at A PointDocument32 paginiEquilibruim of Forces and How Three Forces Meet at A PointSherif Yehia Al MaraghyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advantages of Using Mobile ApplicationsDocument30 paginiAdvantages of Using Mobile ApplicationsGian Carlo LajarcaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Use Visual Control So No Problems Are Hidden.: TPS Principle - 7Document8 paginiUse Visual Control So No Problems Are Hidden.: TPS Principle - 7Oscar PinillosÎncă nu există evaluări

- PowerPointHub Student Planner B2hqY8Document25 paginiPowerPointHub Student Planner B2hqY8jersey10kÎncă nu există evaluări

- Form 4 Additional Mathematics Revision PatDocument7 paginiForm 4 Additional Mathematics Revision PatJiajia LauÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statistical Quality Control, 7th Edition by Douglas C. Montgomery. 1Document76 paginiStatistical Quality Control, 7th Edition by Douglas C. Montgomery. 1omerfaruk200141Încă nu există evaluări

- Returnable Goods Register: STR/4/005 Issue 1 Page1Of1Document1 paginăReturnable Goods Register: STR/4/005 Issue 1 Page1Of1Zohaib QasimÎncă nu există evaluări

- United-nations-Organization-uno Solved MCQs (Set-4)Document8 paginiUnited-nations-Organization-uno Solved MCQs (Set-4)SãñÂt SûRÿá MishraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consumers ' Usage and Adoption of E-Pharmacy in India: Mallika SrivastavaDocument16 paginiConsumers ' Usage and Adoption of E-Pharmacy in India: Mallika SrivastavaSundaravel ElangovanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Committee History 50yearsDocument156 paginiCommittee History 50yearsd_maassÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bala Graha AfflictionDocument2 paginiBala Graha AfflictionNeeraj VermaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dolni VestoniceDocument34 paginiDolni VestoniceOlha PodufalovaÎncă nu există evaluări

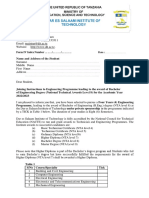

- Joining Instruction 4 Years 22 23Document11 paginiJoining Instruction 4 Years 22 23Salmini ShamteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journals OREF Vs ORIF D3rd RadiusDocument9 paginiJournals OREF Vs ORIF D3rd RadiusironÎncă nu există evaluări

- Flexible Regression and Smoothing - Using GAMLSS in RDocument572 paginiFlexible Regression and Smoothing - Using GAMLSS in RDavid50% (2)

- Big Joe Pds30-40Document198 paginiBig Joe Pds30-40mauro garciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment - Final TestDocument3 paginiAssignment - Final TestbahilashÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study IndieDocument6 paginiCase Study IndieDaniel YohannesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alignment of Railway Track Nptel PDFDocument18 paginiAlignment of Railway Track Nptel PDFAshutosh MauryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revit 2010 ESPAÑOLDocument380 paginiRevit 2010 ESPAÑOLEmilio Castañon50% (2)

- Shouldice Hospital Ltd.Document5 paginiShouldice Hospital Ltd.Martín Gómez CortésÎncă nu există evaluări

- Price List PPM TerbaruDocument7 paginiPrice List PPM TerbaruAvip HidayatÎncă nu există evaluări

- CFO TagsDocument95 paginiCFO Tagssatyagodfather0% (1)

- Dep 32.32.00.11-Custody Transfer Measurement Systems For LiquidDocument69 paginiDep 32.32.00.11-Custody Transfer Measurement Systems For LiquidDAYOÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Dominant Regime Method - Hinloopen and Nijkamp PDFDocument20 paginiThe Dominant Regime Method - Hinloopen and Nijkamp PDFLuiz Felipe GuaycuruÎncă nu există evaluări