Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Ascomycota

Încărcat de

sujithasDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Ascomycota

Încărcat de

sujithasDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Ascomycota

Ascomycota is a Division/Phylum of the kingdom Fungi that, together with the Basidiomycota, form the subkingdom Dikarya. Its members are commonly known as the sac fungi. They are the largest phylum of Fungi, with over 64,000 species.[2] The defining feature of this fungal group is the "ascus" (from Greek : (askos), meaning "sac" or "wineskin"), a microscopic sexual structure in which nonmotile spores, called ascospores, are formed. However, some species of the Ascomycota are asexual, meaning that they do not have a sexual cycle and thus do not form asci or ascospores. Previously placed in the Deuteromycota along with asexual species from other fungal taxa, asexual (or anamorphic) ascomycetes are now identified and classified based on morphological or physiological similarities to ascus-bearing taxa, and by phylogenetic analyses of DNA sequences.[3][4] The ascomycetes are a monophyletic group, i.e., all of its members trace back to one common ancestor. This group is of particular relevance to humans as sources for medicinally important compounds, such as antibiotics and for making bread, alcoholic beverages, and cheese, but also as pathogens of humans and plants. Familiar examples of sac fungi include morels, truffles, brewer's yeast and baker's yeast, dead man's fingers, and cup fungi. The fungal symbionts in the majority of lichens (loosely termed "ascolichens") such as Cladonia belong to the Ascomycota. There are many plant-pathogenic ascomycetes, including apple scab, rice blast, the ergot fungi, black knot, and the powdery mildews. Several species of ascomycetes are biological model organisms in laboratory research. Most famously Neurospora crassa, several species of yeasts, and Aspergillus species are used in many genetics and cell biology studies. Penicillium species on cheeses and those producing antibiotics for treating bacterial infectious diseases are examples 7.2 Heterokaryosis and parasexualityAscomycetes

versus Ascomycota

Before the recognition of the fungal kingdom, the sac fungi were considered to be a class, not a phylum . The original collective term for these taxa was "Ascomycetes", which was first coined in the 1800s for a rankless nonlichenized taxon that possessed asci. The names Ascomycota, Ascomycetes, and others with the same root are based upon the term "ascus". "Ascomycetes" was soon used to include lichenized taxa, and became the standard term, at the class level, for all ascus-bearing species, just as the term "Basidiomycetes" became used for their basidium-bearing counterparts. Elevation of the taxonomic rank of the Ascomycetes resulted in the names Ascomycetae, Ascomycotina, and finally Ascomycota. Together, the Ascomycota and the Basidiomycota form the subkingdom Dikarya. The more familiar term, Ascomycetes, is still loosely used, e.g. at fungal forays it is often said of a fungus, such as Peziza, "It is an ascomycete, not a basidiomycete" in reference to their sexual reproductive mode. The terms are further abbreviated to "ascos" and "basidos", which are not officially sanctioned technical names.

Modern classification of Ascomycota

There are three subphyla that are described and accepted:

The Pezizomycotina are the largest subphylum and contains all ascomycetes that produce ascocarps (fruiting bodies), except for one genus, Neolecta, in the Taphrinomycotina. It is roughly equivalent to the previous taxon, Euascomycetes. The Pezizomycotina includes most macroscopic "ascos" such as truffles, ergot, ascolichens, cup fungi (discomycetes), pyrenomycetes, lorchels, and caterpillar fungus.[1] It also contains microscopic fungi such as powdery mildews, dermatophytic fungi, and Laboulbeniales. The Saccharomycotina comprise most of the "true" yeasts, such as baker's yeast and Candida, which are single-celled (unicellular) fungi, which reproduce vegetatively by budding. Most of these species were previously classified in a taxon called Hemiascomycetes. The Taphrinomycotina include a disparate and basal group within the Ascomycota that was recognized following molecular (DNA) analyses. The taxon was originally named Archiascomycetes (or Archaeascomycetes). It includes both hyphal fungi (Neolecta, Taphrina, Archaeorhizomyces), fission yeasts (Schizosaccharomyces), and the mammalian lung parasite, Pneumocystis.

Ribosomal RNA gene sequencing of soil suggests that there may be a fourth subphylum of Ascomycota (termed Soil Clone Group I or SCGI), that has not been described in cultures or based on fruiting bodies. SCGI organisms are only known from DNA sequences found in soils worldwide and are placed between the Taphriomycotina and the Saccharomycotina. [5][6]

Outdated taxon names

Several outdated taxon namesbased on morphological featuresare still occasionally used for species of the Ascomycota. These include the following sexual (teleomorphic) groups, defined by the structures of their sexual fruiting bodies: the Discomycetes, which included all species forming apothecia; the Pyrenomycetes, which included all sac fungi that formed perithecia or pseudothecia, or any structure resembling these morphological structures; and the Plectomycetes, which included those species that form cleistothecia. Hemiascomycetes included the yeasts and yeast- like fungi that have now been placed into the Saccharomycotina or Taphrinomycotina, while the Euascomycetes included the remaining species of the Ascomycota, which are now in the Pezizomycotina, and the Neolecta, which are in the Taphrinomycotina. Some ascomycetes do not reproduce sexually or are not known to produce asci and are therefore anamorphic species. Those anamorphs that produce conidia (mitospores) were previously described as Mitosporic Ascomycota. Some taxonomists placed this group into a separate artificial phylum, the Deuteromycota (or "Fungi Imperfecti"). Where recent molecular analyses have identified close relationships with ascus-bearing taxa, anamorphic species have been grouped into the Ascomycota, despite the absence of the defining ascus. Sexual and asexual isolates of the same species commonly carry different binomial species names, as, for example, Aspergillus nidulans and Emericella nidulans, for asexual and sexual isolates, respectively, of the same species. Species of the Deuteromycota were classified as Coelomycetes if they produced their conidia in minute flask- or saucer-shaped conidiomata, known technically as pycnidia and acervuli.[7] The Hyphomycetes were those species where the conidiophores (i.e., the hyphal structures that carry

conidia- forming cells at the end) are free or loosely organized. They are mostly isolated but sometimes also appear as bundles of cells aligned in parallel (described as synnematal) or as cushion-shaped masses (described as sporodochial ).[8]

Morphology

A member of the Cordyceps genus which is parasitic on arthropods. Note the elongated ascocarps. Species unknown, perhaps Cordyceps ignota. Most species grow as filamentous, microscopic structures called hyphae. Many interconnected hyphae form a mycelium, whichwhen visible to the naked eye (macroscopic) is commonly called mold (or, in botanical terminology, thallus). During sexual reproduction, many Ascomycota typically produce large numbers of asci. The asci is often contained in a multicellular, occasionally readily visible fruiting structure, the ascocarp (also called an ascoma). Ascocarps come in a very large variety of shapes: cup-shaped, club-shaped, potato-like, spongy, seed-like, oozing and pimple- like, coral- like, nit- like, golf-ball- shaped, perforated tennis balllike, cushion-shaped, plated and feathered in miniature (Laboulbeniales), microscopic classic Greek shield-shaped, stalked or sessile. They can appear solitary or clustered. Their texture can likewise be very variable, including fleshy, like charcoal (carbonaceous), leathery, rubbery, gelatinous, slimy, powdery, or cob-web- like. Ascocarps come in multiple colors such as red, orange, yellow, brown, black, or, more rarely, green or blue. Some ascomyceous fungi, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, grow as single-celled yeasts, whichduring sexual reproduction develop into an ascus, and do not form fruiting bodies.

The "candlesnuff fungus", Xylaria hypoxylon In lichenized species, the thallus of the fungus defines the shape of the symbiotic colony. Some dimorphic species, such as Candida albicans, can switch between growth as single cells and as filamentous, multicellular hyphae. Other species are pleomorphic, exhibiting asexual (anamorphic) as well as a sexual (teleomorphic) growth forms. Except for lichens, the non-reproductive (vegetative) mycelium of most ascomycetes is usually inconspicuous because it is commonly embedded in the substrate, such as soil, or grows on or inside a living host, and only the ascoma may be seen when fruiting. Pigmentation, such as melanin in hyphal walls, along with prolific growth on surfaces can result in visible mold colonies; examples include Cladosporium species, which form black spots on bathroom caulking and other moist areas. Many ascomycetes cause food spoilage, and, therefore, the pellicles or moldy layers that develop on jams, juices, and other foods are the mycelia of these species or occasionally Mucoromycotina and almost never Basidiomycota. Sooty molds that develop on plants, especially in the tropics are the thalli of many species. [clarification needed ]

The ascocarp of a morel contains numerous apothecia. Large masses of yeast cells, asci or ascus- like cells, or conidia can also form macroscopic structures. For example. Pneumocystis species can colonize lung cavities (visible in x-rays), causing a form of pneumonia.[9] Asci of Ascosphaera fill honey bee larvae and pupae causing mummification with a chalk- like appearance, hence the name "chalkbrood". [10] Yeasts for small colonies in vitro and in vivo, and excessive growth of Candida species in the mouth or vagina causes "thrush", a form of candidiasis. The cell walls of the ascomycetes almost always contain chitin and -glucans, and divisions within the hyphae, called "septa", are the internal boundaries of individual cells (or compartments). The cell wall and septa give stability and rigidity to the hyphae and may prevent loss of cytoplasm in case of local damage to cell wall and cell membrane. The septa commonly have a small opening in the center, which functions as a cytoplasmic connection between adjacent cells, also sometimes allowing cell- to-cell movement of nuclei within a hypha. Vegetative hyphae of most ascomycetes contain only one nucleus per cell ( uninucleate hyphae), but multinucleate cellsespecially in the apical regions of growing hyphaecan also be present.

Metabolism

In common with other fungal phyla, the Ascomycota are heterotrophic organisms that require organic compounds as energy sources. These are obtained by feeding on a variety of organic substrates including dead matter, foodstuffs, or as symbionts in or on other living organisms. To obtain these nutrients from their surroundings, ascomycetous fungi secrete powerful digestive enzymes that break down organic substances into smaller molecules, which are then taken up into the cell. Many species live on dead plant material such as leaves, twigs, or logs. Several species colonize plants, animals, or other fungi as parasites or mutualistic symbionts and derive all their metabolic energy in form of nutrients from the tissues of their hosts. Owing to their long evolutionary history, the Ascomycota have evolved the capacity to break down almost every organic substance. Unlike most organisms, they are able to use their own enzymes to digest plant biopolymers such as cellulose or lignin. Collagen, an abundant structural protein in animals, and keratina protein that forms hair and nails, can also serve as food sources. Unusual examples include Aureobasidium pullulans, which feeds on wall paint, and the kerosene fungus Amorphotheca resinae, which feeds on aircraft fuel (causing occasional problems for the airline industry), and may sometimes block fuel pipes. [11] Other species can resist high osmotic stress and grow, for example, on salted fish, and a few ascomycetes are aquatic. The Ascomycota is characterized by a high degree of specialization; for instance, certain species of Laboulbeniales attack only one particular leg of one particular insect species. Many Ascomycota engage in symbiotic relationships such as in lichens symbiotic associations with green algae or cyanobacteria in which the fungal symbiont directly obtains products of photosynthesis. In common with many basidiomycetes and Glomeromycota, some ascomycetes

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- 25 (Number) : in MathematicsDocument3 pagini25 (Number) : in MathematicssujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- 23Document3 pagini23sujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- ThursdayDocument2 paginiThursdaysujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- Medical Terminology AbbreviationsDocument4 paginiMedical Terminology AbbreviationsKat Mapatac100% (2)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- 13Document3 pagini13sujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- SundayDocument3 paginiSundaysujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- 11 (Number) : in MathematicsDocument3 pagini11 (Number) : in MathematicssujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Everything about the number 22Document3 paginiEverything about the number 22sujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- 20 (Number) : in MathematicsDocument3 pagini20 (Number) : in MathematicssujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- In Common Usage and Derived Terms: DecimateDocument3 paginiIn Common Usage and Derived Terms: DecimatesujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPT Code Guidelines For Nuclear Medicine and PETDocument2 paginiCPT Code Guidelines For Nuclear Medicine and PETsujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- WednesdayDocument3 paginiWednesdaysujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- December: December (Disambiguation) Dec January February March April May June July August September October NovemberDocument3 paginiDecember: December (Disambiguation) Dec January February March April May June July August September October NovembersujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Onday: Hide Improve It Talk Page Verification Cleanup Quality StandardsDocument2 paginiOnday: Hide Improve It Talk Page Verification Cleanup Quality StandardssujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- SeptemberDocument5 paginiSeptembersujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- October: October Events and HolidaysDocument3 paginiOctober: October Events and HolidayssujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- AugustDocument3 paginiAugustsujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- NovemberDocument2 paginiNovembersujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- JulyDocument2 paginiJulysujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- June Month Facts and EventsDocument3 paginiJune Month Facts and EventssujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- FebruaryDocument4 paginiFebruarysujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- May - The Month of Spring in the Northern HemisphereDocument4 paginiMay - The Month of Spring in the Northern HemispheresujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- PectinDocument4 paginiPectinsujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- AprilDocument3 paginiAprilsujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- JanuaryDocument3 paginiJanuarysujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cellular RespirationDocument3 paginiCellular RespirationsujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- March 1Document4 paginiMarch 1sujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- SeptemberDocument5 paginiSeptembersujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Cell WallDocument4 paginiCell WallsujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cell MembraneDocument3 paginiCell MembranesujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Reactive Chemicals - Guardian Environmental TechnologiesDocument69 paginiList of Reactive Chemicals - Guardian Environmental TechnologiesGuardian Environmental TechnologiesÎncă nu există evaluări

- C4 ISRchapterDocument16 paginiC4 ISRchapterSerkan KalaycıÎncă nu există evaluări

- PeopleSoft Security TablesDocument8 paginiPeopleSoft Security TablesChhavibhasinÎncă nu există evaluări

- PowerPointHub Student Planner B2hqY8Document25 paginiPowerPointHub Student Planner B2hqY8jersey10kÎncă nu există evaluări

- Open Far CasesDocument8 paginiOpen Far CasesGDoony8553Încă nu există evaluări

- Mrs. Universe PH - Empowering Women, Inspiring ChildrenDocument2 paginiMrs. Universe PH - Empowering Women, Inspiring ChildrenKate PestanasÎncă nu există evaluări

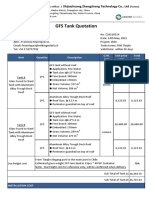

- GFS Tank Quotation C20210514Document4 paginiGFS Tank Quotation C20210514Francisco ManriquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper SizeDocument22 paginiPaper SizeAlfred Jimmy UchaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evil Days of Luckless JohnDocument5 paginiEvil Days of Luckless JohnadikressÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment Gen PsyDocument3 paginiAssignment Gen PsyHelenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Galaxy Owners Manual Dx98vhpDocument10 paginiGalaxy Owners Manual Dx98vhpbellscbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian Standard: Pla Ing and Design of Drainage IN Irrigation Projects - GuidelinesDocument7 paginiIndian Standard: Pla Ing and Design of Drainage IN Irrigation Projects - GuidelinesGolak PattanaikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civil Service Exam Clerical Operations QuestionsDocument5 paginiCivil Service Exam Clerical Operations QuestionsJeniGatelaGatillo100% (3)

- Alternate Tuning Guide: Bill SetharesDocument96 paginiAlternate Tuning Guide: Bill SetharesPedro de CarvalhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- France Winckler Final Rev 1Document14 paginiFrance Winckler Final Rev 1Luciano Junior100% (1)

- !!!Логос - конференц10.12.21 копіяDocument141 pagini!!!Логос - конференц10.12.21 копіяНаталія БондарÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journals OREF Vs ORIF D3rd RadiusDocument9 paginiJournals OREF Vs ORIF D3rd RadiusironÎncă nu există evaluări

- Draft SemestralWorK Aircraft2Document7 paginiDraft SemestralWorK Aircraft2Filip SkultetyÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Microfinance in NigeriaDocument9 paginiHistory of Microfinance in Nigeriahardmanperson100% (1)

- Price List PPM TerbaruDocument7 paginiPrice List PPM TerbaruAvip HidayatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Google Earth Learning Activity Cuban Missile CrisisDocument2 paginiGoogle Earth Learning Activity Cuban Missile CrisisseankassÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluative Research DesignDocument17 paginiEvaluative Research DesignMary Grace BroquezaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors of Active Citizenship EducationDocument2 paginiFactors of Active Citizenship EducationmauïÎncă nu există evaluări

- Template WFP-Expenditure Form 2024Document22 paginiTemplate WFP-Expenditure Form 2024Joey Simba Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 4 DeterminantsDocument3 paginiChapter 4 Determinantssraj68Încă nu există evaluări

- Oxygen Cost and Energy Expenditure of RunningDocument7 paginiOxygen Cost and Energy Expenditure of Runningnb22714Încă nu există evaluări

- Gabinete STS Activity1Document2 paginiGabinete STS Activity1Anthony GabineteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chromate Free CoatingsDocument16 paginiChromate Free CoatingsbaanaadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Done - NSTP 2 SyllabusDocument9 paginiDone - NSTP 2 SyllabusJoseph MazoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peran Dan Tugas Receptionist Pada Pt. Serim Indonesia: Disadur Oleh: Dra. Nani Nuraini Sarah MsiDocument19 paginiPeran Dan Tugas Receptionist Pada Pt. Serim Indonesia: Disadur Oleh: Dra. Nani Nuraini Sarah MsiCynthia HtbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityDe la EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2)

- The Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and BehaviorDe la EverandThe Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and BehaviorEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (137)

- Crypt: Life, Death and Disease in the Middle Ages and BeyondDe la EverandCrypt: Life, Death and Disease in the Middle Ages and BeyondEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (3)

- All That Remains: A Renowned Forensic Scientist on Death, Mortality, and Solving CrimesDe la EverandAll That Remains: A Renowned Forensic Scientist on Death, Mortality, and Solving CrimesEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (396)

- Masterminds: Genius, DNA, and the Quest to Rewrite LifeDe la EverandMasterminds: Genius, DNA, and the Quest to Rewrite LifeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseDe la EverandDark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (69)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe la EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2)