Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Lettering Music Title Pages

Încărcat de

Ingrid Calvo IvanovicDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Lettering Music Title Pages

Încărcat de

Ingrid Calvo IvanovicDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The lettering on lithographed music title pages of the nineteenth century Bart Blubaugh

Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Typeface Design, University of Reading, 2003

Fig. i. T. Bonheur, Cloudland (London: 1880s). Colour lithograph [publisher missing] 243 x 336 mm.

Abstract Three groups into which the lettering on lithographed music title pages can be separated are lettering that acts as an object within the picture, lettering that exists without any picture, and lettering that is ornamental without being representational. Drawn lettering on lithographed music title pages of the nineteenth century first imitates that seen on engraved music title pages. One artist who freel experimented primarily with lettering on music title pages is T.W. Lee. Rustic lettering used by Victorian illustrators is copied by lithographers, and leads to further variations of the Rustic letter. Ornamental typefaces influence and are influenced by the designs of lettering used on these title pages. The advent of colour lithography allows further experiment of how letters are presented . Lithography also influences letterpress printing, particularly the Artistic Printing movement. Artistic printing is marked by an increase in ornament combined with type, and especially an abundance of rules to separate elements.

INTRODUCTION Lithographed title pages for sheet music of the nineteenth century exhibit a variety of expressive lettering unparalleled by other graphic arts techniques. Investigating various influences on the artists and delineators who created this lettering may help bring to light this lettering developed There are three basic categories of lettering. One: lettering that is represented as if it were an object within the picture included on the title page. The lettering may be covered with snow and icicles within a winter scene, or falling from the sky as if pieces from a toppled building. Two: lettering that is alone on the title page. This lettering may simply be a drawn imitation of an ornamental typeface, or it may be more decorative. It may exhibit the traits of a three dimensional object existing in perspective and casting a shadow. Three: lettering that is purely decorative in nature, and not imitative of anything existing in nature, including ornamental typefaces. The earliest lithographed music title pages imitated the design pattern developed for engraving, using the copperplate script and calligraphic flourishes in tandem with a vignette. Eventually lithographic artists break out of this mould and the artist freely invents lettering associated only with the tools used for lithography. One artist who explored a variety of lettering styles was T.W. Lee. Illustrators whose worked was reproduced with wood engraving experimented with a kind of lettering grown from twigs and branches. This Rustic lettering would also influence ornamental typefaces. Rustic lettering was popular during the nineteenth century, and it was used frequently in lithographed music title pages. Branches or tree trunks could be bent, cut or grown to form lettering unique to one single title page, unlike the Rustic typefaces. Variations developed from this kind of lettering, becoming flat instead of having form and shadow, acting more like lightening than wood, as well as having carefully formed serifs. Ornamented typefaces either provide material for the lithographic artists to use, or they imitate the work of lithographers. Tuscan, perspective, rustics, and Latin-Runics, among other nineteenth century ornamented types, are all visible in these lithographed title pages. Lithography allowed word and picture to combine differently than previous graphic arts processes, and colour lithography offered even more opportunity for experiment to the lithographers.

Colour was used in new ways to create visual interest and relationships between the lettering and the picture. Letterpress printing styles also followed lithographys lead, particularly in Artistic Printing toward the last decades of the century. Victorian book designers who experimented with lettering they found in medieval manuscripts were influential to the lithographed lettering of music title pages. Artists such as H.N. Humphreys, who imitated Rustic lettering in his beautifully, illustrated gift books.

CHAPTER 1 Nomenclature There are two categories of nineteenth century English illustrated music title pages, as defined by one author. One category includes title pages that are ornamental or decorative in their design. These cover designs do not often provide descriptive illustration of the musics subject, but only a nice decoration that may be enticing to a potential buyer. In general, this type of title page is for serious music. The other category is pictorial, with imagery that is representational and illustrative of the subject of the music. These title pages use imagery that relates in some way to the music itself, such as a scene describing the song, or a musical instrument. The author who describes these two categories writes the true pictorial music title page always owes its design to the nature of the music: in decorative title pages, the connexion is of the slightest, if indeed it exists at all (King 1950, p 263). These two methods of defining title pages are adequate for looking at the entire design: picture with words and decoration with words. To categorize only the styles of lettering, the ways in which the words are drawn, can result in a number of possible definitions. Separating the display lettering of music title pages into groups may provide an easier way of following the possible influences on this type of lettering. In one group, the word is

1.1. L. Stern, The Catastrophe Galop (London: c. 1860). Colour lithograph [London: Augener & Co.] 255 x 331 mm.

1.2. W.T. Wrighton, The Wishing Cap (London: c. 1860). Colour lithograph [London: Robert Cocks & Co.] 250 x 349 mm.

integrated into the image so that the letters become objects subject to the environment of the cover illustration (fig. 1.1). These letters may be involved in the illustrations drama in some way, or they may be merely providing the verbal message while keeping a distance from the focal point of the illustration, yet still affected by the natural laws at work in the picture (fig. 1.2). Another group includes the title pages that have lettering only and no illustration. Sometimes the lettering is clearly imitating an existing single typeface or category of typeface design (fig. 1.3, 1.4). Compare the top line of lettering in figure 1.4a with the two line Tuscan typeface in figure 1.4b. Within this category are also title pages with lettering that becomes a kind of illustration. Some of these illustrated letters provide an interpretation of the meaning of the words displayed (fig. 1.5). Others simply provide lettering that steps out of the normal two dimensional plane writing is accustomed to and perform as an illustration, although not an illustration that provides any clues as to the content of the music inside (fig. 1.6). Another group contains lettering that is primarily decorative, whether a picture is included or not (fig. 1.7, 1.8). This lettering may be expressive of a mood or atmosphere, but it is separate from any illustration present or it is not acting as a picture if there is no other image.

1.4b. English two-line Tuscan, Alexander Wilson & Sons 1843 (Gray, 1976, fig. 98).

1.3.. J. Pridham, Yorkshire bells (London: c. 1875). Lithograph [London: Brewer & Co].

1.4a. E. Waldteufel, Pluie dor valse (London: c. 1800s). Colour lithograph [London: Hopwood & Crew] 256 x 341 mm.

1.5. A.P. Wyman, Silvery waves (c. 1800s). Lithograph [Reading: W. Hickie] 265 x 362 mm.

1.6. Calcott, All the rage (London: 1860s). Colour lithograph [London: Cramer & Co.] 255 x 348 mm.

1.7. P. Bucalosi, The Gondoliers (London: after 1857). Lithograph [London: Chappell & Co.] 240 x 330 mm.

1.8. O. Roeder, Fairy tales waltz (London: c. 1800s). Colour lithograph [London: Enoch & Sons] 254 x 337 mm.

Among all these groups are letterforms imitative of typefaces. Others go beyond mere type forms to become something not available in metal or wood. The earliest lithographed music title pages imitated the layout form developed for engraving, which was typically English or copperplate script with a word or two in caps, the whole thing held together with calligraphic flourishes (Twyman 1996). The tools for engraving were a graver that the artist would use to dig away the surface of the plate, made of copper or other metal. For the lithographic process, the tools held by the lettering specialist are now a wax crayon or a steel pen or fine brush loaded with ink. The surface is a smooth, polished stone. Images become more important to the layout, possibly because of the competition of increasingly popular music. Lettering also becomes more fanciful. Mechanical type-making methods are introduced late in the third decade and ornamental typefaces become more prolific. This provides lettering artists with a greater variety of letterforms to draw upon for inspiration and imitation (Pearsall). These title pages show lettering that is integrated into the picture in a new way. Engraved music title pages demonstrate considerable skill in combining calligraphic letterforms and

1.11. M. Lindsay, When sparrows build, (London: c. 1895). Lithograph [London: Robert Cocks & Co.] 245 x 330 mm.

1.9. Jullien, lEcho du Mont Blanc (London: c. 1850s). Colour lithograph [London: Jullien & Co.] 239 x 328 mm.

1.10. A. Keller, Mistletoe galop (London: after 1849 ). Colour lithograph [London: Brewer & Co.] 264 x 363 mm.

1.12. C. Coote Jr., Go Bang Galop (London: c. 1880). Colour lithograph [London: Ashdown & Parry] 240 x 324 mm.

1.13. Cotton polka (London: c. 1880). Colour lithograph [London: T. Broome] 235 x 310 mm.

10

flourishing with images, but they also follow an established pattern of lettering and layout (Twyman 1996). Lithographed music title pages go beyond that pattern into a new realm. The lettering may still be separated from the image by some distance, but it now acts as an object suspended in the space of the image. Snow piling on top and icicles hanging from the bottoms of the letters become a common element for winter scenes (figs. 1.9, 1.10). In the second half of the century, images conquer the entire title page. The picture is the most important element, and it is now covering the entire page bleeding off on all the edges. Towards the end of the century, lettering becomes dominant again, and ornament replaces representational images. Most of the lettering artists are not know to us. There is little material available to trace their footsteps. The production staffs of the music printing industry, which may have included lettering specialists, are commonly called delineators in early twentieth century literature on music title pages. In Imesons book for collectors, he writes, Many of the music-title delineators were the mere journeymen of art, though their work may lack neither merit nor interest. Little is known concerning them. Mostly Bohemian in their habits they were hardly the men likely to leave much in the way of written records. They lived freely and had their day then

1.14. Twelve lines Perspective, Bower & Bacon 1837 (Gray 1976, fig. 79).

1.15. C. Coote Jr., The Eclipse Galop (London: 1865). Colour lithograph [London: Hopwood & Crew] 250 x 347 mm.

1.16. Rosalind, Try Again (London: c. 1867). Colour lithograph [London: Hopwood & Crew] 247 x 338 mm.

11

passed into oblivion (Imeson, 1912). One artist about whom some information is available is Thomas Wales Lee (1833-1910). Lee worked with another artist, highly regarded by collectors of music-title pages, Alfred Concanen. Lees covers rely heavily on creating visual interest through fanciful treatment of the words on the page. Able to take advantage of chromolithography, Lee used colour to create letters that imitated perspective ornamented typefaces, or he created lettering that would bend and bow unlike anything available in metal or wood type. Lees lettering is the kind of letterform that becomes an object, but not an object that necessarily conveys a semantic meaning related to the words those letters form. Figures 1.15 and 1.16 show covers by Lee from about 1865. Some lettering clearly imitates the perspective letters available in metal since a few decades previous (fig. 1.14), while other letters mimic a flexible material that has been tacked to the surface of the title page. By the frequency of different music title pages that use this similar style, it is possible that this peculiar treatment of the letters was particularly popular among the music publishers whom Lee worked for, and that Lee was known for it.

1.18. C. Coote Jr., Roulette Galop (London: 1860s). Color lithograph [London: Hopwood & Crew] 264 x 367 mm.

1.19. W.H. Callcot, Rock of ages (London: c. 1870). Lithograph [publisher missing] 215 x 282 mm.

12

Lee worked with several music title-page artists, whose work is highly collectable, including T. Packer and A. Concanen. He was sought after for his fancy letter style of decorative lettering on title pages, and was given the name fancy-title Lee by his colleagues (Imeson 1912).

13

CHAPTER 2 Contemporary Letter Design The Landscape Alphabet, published between 1830-31, is an alphabet book in which each illustrated letter is built from elements in a landscape, such as trees, foliage, and architectural ruins. It was lithographed by the early English lithographer Charles Hullmandel. The idea is linked to the Picturesque art movement. This was the English taste for vignettes of landscape scenes depicting popular subjects such as gothic ruins. The Landscape Alphabet is exactly this, with 26 vignettes of gothic ruins or vegetation contorted into the shape of each letter in the alphabet. It may have been influenced by an aquatint from the title page of an 1812 book, The Tour of Doctor Syntax, in Search of the Picturesque. A Poem. This poem poked fun at the ideas of the Picturesque itself, and the title page depicted a few letters formed from elements within a landscape (Twyman 1987).

2.1. J. Ruskin, The King of the golden river (Sunnyside: 1888). Lithograph [Sunnyside: George Allen].

14

Artists using objects from nature to create letterforms for title pages and illustration continued into the development of the Rustic typeface. The Rustic typeface is based on a simple formula: bend, prune and chop trees, branches and twigs into the shape of each letter in the alphabet. Richard Doyles title page for Ruskins The King of the golden river is an example of engraved lettering which influenced the Rustic style of typeface (fig. 2.1). Engravers working in wood pioneered the rustic letterform, and then typeface manufacturers cut it into wood and metal type (Gray, 1976). Victorian illustrators Doyle and Henry Noel Humphreys both created rustic letterforms. Rustic lettering, and variations derived from it, appears frequently in music title pages (fig. 2.22.9). It was certainly popular, and must have offered lithographic artists an acceptable formula for creating lettering that would gather attention. It also continued to be used late into the nineteenth century (fig. 2.3). Rustic lettering has influenced a number of variations, from the most representational and detailed lettering (fig. 2.4), to the more quickly rendered lettering of Jules Chert (fig. 2.5). Cherts lettering captures the essence of rustic forms, and blends into the image, allowing the illustration to take the most prominent place. Other rustic derivatives hint at sticks with twig-like growths

2.2. C. Marriott, The urchin schottische (London: c. 1860). Lithograph [London: Addison, Hollier & Lucas] 336 x 255 mm.

2.3. T. Bonheur, High jinks quadrilles (London: 1890s). Colour lithograph [publisher cropped] 331 x 230 mm.

15

2.4. M. Hobson, The sunflower schottische (London: c. 1800s). Colour lithograph [London: Hopwood & Crew] 363 x 268 mm.

2.5. J.P. Clark, The witches own galop (London: 1880s). Colour lithograph [London: Cramer & Co.] 349 x 255 mm.

2.6. C. DAlbert, Rip Van Winkle lancers (London: 1880s). Colour lithograph [publisher missing] 236 x 331 mm.

2.7. C.H.R. Marriott, Leap for life (London: c. 1871). Colour lithograph [London: Cramer Wood & Co, Lamborn Cock & Co.] 221 x 358 mm.

16

protruding from the letterforms, all of it flattened instead of using form and shadow (fig. 2.6, 2.7). Rustic typefaces begin to appear in the specimen books in the 1840s (Gray, 1976; Twyman, 1987). Typefaces can only offer a limited number of letter shapes, and repeating letters in word or line must then look alike. Shadows and shadow outlines are added, as well as vertical serifs (fig. 2.2). Lithographic artists are able to transform their lettering into multiple shapes, each one unique in

2.4b. Two-line pica rustic no. 1. Figgins c. 1846 (Gray 1976, fig. 88).

2.4a. Three lines long primer rustic, twoline small pica rustic. Figgins, 1845 (Gray 1976, figs. 86, 87).

2.8. W. Macfarlane, Echoes from the pantomime, Babes in the wood quadrille (1877). Colour lithograph [publisher missing] 240 x 335 mm.

2.9a. J.F. Mitchell Gilhooleys supper-party (London: c. 1880s). Lithograph [London: Francis Bros. & Day] 238 x 338 mm.

2.9b J.F. Mitchell Gilhooleys supper-party (London: c. 1880s). Lithograph [London: Francis Bros. & Day] 238 x 338 mm.

17

its appearance, as well as create an envelope to shape an entire line or word appropriate to the frame devised for the title-page. Similar expressive lettering found in Doyles illustrations for The King of the Golden River is that used for the calling card of one of the books characters (fig. 2.2). The Victorian illustrator George Cruickshank (Phiz), who also illustrated a few music title pages, uses a similarly expressive letter on the cover of Better late than never! (fig. 2.3). Cruickshanks lettering, with its overlapping of outlined strokes, bears similarities with the kind of sign-writing described by Callingham in his 1871 book Sign writing and glass embossing. Callingham provides an exercise for the sign-writer apprentice. An example of the word LAND is shown with drawn letterforms that overlap in places. The student is to use this lettering as an example and to create an entire alphabet that will match the example given (Callingham 1871).

2.10. J. Ruskin, The King of the golden river (Sunnyside: 1888). Lithograph [Sunnyside: George Allen].

2.11. C. Glover, Better late than never! (London: c. 1860). Colour lithograph [London: Addison, Hollier & Lucas] 214 x 328 mm.

18

Ornamented typefaces often either mimicked or influenced the lettering in lithographed music title pages. A number of authors suggest that nineteenth century type designers looked toward the lettering of lithography and sign writing for their designs (Callingham 1871, Gray 1976). Ray Nash (Gray, 1976) provides a quote from the Electrotype Journal of July, 1874 indicating the influence lithographic lettering had on type design in the USA: Many and strenuous efforts have been made in late years by artistic printers to reproduce in certain contingencies the graceful effects of lithography. These efforts have been largely seconded on the part of type founders and others by the introduction of beautiful arrays of script and ornamental type, graceful brass and metal flourishes, brass curves, and other devices (Gray 1976, p 122). One form of ornamented typeface from the Victorian era is the Tuscan. Serifs that split the stroke at the terminals mark the Tuscan letter. In addition, a bulge, pointed or not, is sometimes added to the center of the letter. The typeface examples in figure 2.12 are

2.12. Three-line pica Lord Mayor and Pretty Face, Woods Typographical Advertiser, 1862 (Gray 1976, figs. 139, 137).

2.13. W. Keller, The Czars marche (London: 1880s). Colour lithograph [London: Brewer & Co.] 225 x 344 mm.

2.14. A.S.E. Rae, The America (London: 1851). Lithograph [London: C. Lonsdale] 229 x 312 mm.

19

both from 1862 (see also figure 1.4b), but the Tuscan style appears throughout the nineteenth century (Gray 1976). The Czars March (fig. 2.13) shows a clear Tuscan letterform, the vertical strokes becoming two separate lines splitting once in the center of the letters to form a diamond shaped opening, and again at the terminals. The America (fig. 2.14) title page

2.15. Five lines and four lines Latin condensed, Stephenson Blake c. 1875 (Gray 1976, fig. 163).

2.16a. J. Coward, Romah waltz (London: 1870s). Colour lithograph [London: Charles Seaton] 241 x 338 mm.

2.17. A.E. Godfrey, The Piccaninnies (London: c. 1895). Colour lithograph [London: Robert Cocks & Co.] 228 x 322 mm.

2.16b. J. Coward, Romah waltz (London: 1870s). Colour lithograph [London: Charles Seaton] 241 x 338 mm.

20

shows Tuscan inspired lozenge in the center, but with a sans-serif terminal. This example is from 1851. Another variety of ornamented typeface seen in music title pages is the Latin-Runic (fig. 2.7). This style is marked by a triangular or swelling serif ending that has a flat cut across the stroke terminal, or a concave indent (Ovink 1972). Romah (fig. 1.16a, 1.16b) is one possible example of the LatinRunic family influencing a lithographed letterform. This title page dates from the 1870s, and the typeface example (fig. 2.15) is from the Stephenson, Black type specimen of 1875 (Gray 1976). Towards the end of the century, there are typefaces and lettering styles that show a calligraphic influence. The typeface Rhodesian appears in 1895 (fig. 2.18) and Graphic in 1896 (fig. 2.19). The music title page for The Piccaninnies (fig. 2.17) is dated the same year as Rhodesian. Rhodesian, Graphic and the lettering for The Piccaninnies all share the swelling of the stroke near the terminal, where the stroke ends with a smooth cut or a rough edge as if a thick brush loaded with paint had formed the letter. The strokes of the letters themselves follow a curving path many times in places where a straight line is expected.

2.18. Graphic, Stephenson, Blake 1896 (Gray 1976, no. 431).

2.19. Two-line double pica Rhodesian, Figgins 1895 (Gray 1976, fig. 217).

21

CHAPTER 3 Printing techniques & contemporary art movements Intaglio printing techniques, such as engraving on copperplates, were used mostly for reproducing imagery. Relief printing, such as letterpress with wood and metal type, was used primarily for words. Lithography eventually provided a reproduction process wherein writing and drawing could be combined more easily than either of the two other printing techniques, and with the popularity of sheet music in the nineteenth century, this combining of writing and image became more important (Twyman, 2001). Beginning in the 1840s, chromolithography allowed writing to be integrated into the printing process in ways not evident in other printing techniques. Figure 3.1 shows the title Skating Polka stopped out, possibly with gum arabic, on the stone that carried black ink. A brown tint was allowed to print in the same area where the black was stopped out. This allowed an interesting way to achieve lettering in a color that is lighter in value than the area surrounding it. It creates enough contrast to allow the title to be read, and it allows the picture to be the first thing a viewers eyes are drawn to. Figure 3.2 shows a similar technique, except all the colours

3.1. G. Alary, Skating polka (London: 1800s). Colour lithograph [publisher missing] 199 x 298 mm.

3.2. L.A. Jullien, The cricket polka (London: 1840s). Colour lithograph [London: ullien] 206 x 299 mm.

22

have been stopped out to allow the lettering to be entirely white. In accordance with the humorous nature of the image the lettering is bolder by way of the stark contrast. In another title page by T. W. Lee, color has been used to give the lettering the same pattern found on the figure (fig. 3.3). The lettering is filled with the same red and black tartan Rob Roy is wearing in the illustration. In figures 3.4 and 3.5 one colour has been used to overprint another, to take advantage of either transparent ink or space within the letterforms through which the color underneath is visible. The decade of the 1840s was an important one for display lettering. More new ornamented typefaces appear during this decade than had occurred yet within the nineteenth century (Gray 1976).

3.3. J.H. Tully, New Rob Roy quadrille (London: 18??). Colour lithopgraph [London: Hutchings & Romer] 355 x 255 mm.

23

3.4. J. Arnold, Timbres poste polka (London: c. 1875). Colour lithograph [Schott Frres] 337 x 242 mm.

3.5. Kalozdy, The Times galop (London: c. 1853). Colour lithograph [London: H. Distin] 339 x 250 mm.

3.6. A. Macey, Mischief schottische (London: 1800s). Lithograph [London: W.H. Boone] 355 x 265 mm.

3.7. W. Williams, Vivacit lancers (London: 1880s). Colour lithograph [London: R. Maynard] 339 x 240 mm.

24

The Gothic revival has left behind the contrivances of the picturesque, and become not a style but a language; like scholastic philosophy, a world in which the mind could freely move (Gray 1976, p 49). It allowed Gray writes It is a significant point that by 1840 letters had so far become a medium to the Victorians that they were able to catch this spirit of the time of passion and fantasy without resorting to Gothic models; the first new black letter type after 1815 was not till November 1847 (Gray 1976, p 50). This is the decade perspective (fig. 1.16) and rustic (see Chapter 2) letters appear, as well as Tuscan (fig. 1.4b, 2.12). During this time also the Grecian types appear. These are characterized by cutting off the corners of the letters. The Rounded is a sans serif with the corners missing, but smoothed into a semicircle rather than a straight cut (Gray 1976).

3.8. P. Bucalosi, The Mikado lancers (London: 1880s). [London: Chappell & Co.] 338 x 238 mm.

25

Towards the close of the nineteenth century, advances in the graphic arts gave rise to artistic printing. The jobbing platen and the point system together provided printers the opportunity to combine complicated patterns of ornament with type. Artistic printing also helped them to compete with lithography (Ridler 1948). Ruskin also encouraged the use of ornament: It seems to me also that a lovely field of design is open in the treatment of decorative type not in the mere big initial in which one cannot find the letter but in the delicate and variably fantastic ornamentation of capitals and filling of blank spaces or musicallydivided periods and breadths of margin (Ridler, 1948). In figures 1.7 and 3.5 there are examples of lettering that becomes very ornamental. Figure 3.6 continues this in chromolithography. The strokes or serif-like terminals in Vivacit curl, twist and grow outward. The lettering itself is not confined to a box as metal type might be. It floats along a moving line, like something resting on the surface of water. In the Leicester Free style is an artistic printing formula that utilizes rules, whether straight, bent or curved, and words positioned so that they have little relationship to one another. The use of the rules seems a logical attempt to simulate the kind of ornament seen in music title pages like figure 3.5. In the second half of the century, there is also an interest in things Asian. Lettering like that for The Mikado (fig. 3.6) and Constantinople (fig. 3.7) is obvious in its attempt to simulate script other than the Latin alphabet. Ornament becomes not just decorative, but language. Not a real language that can be understood by anyone, but an imitation of the kinds of marks used to form these non-Latin scripts.

26

CHAPTER 4 Influence of Victorian book design In Ruari McLeans work on books created during the Nineteenth century in England he makes the following statement: The enthusiasm for the art of illumination generated by Owen Jones, Noel Humphries, and their assistants and imitators created a small body of informed but largely antiquarian taste. It did not have much influence on the art of lettering as practiced up and down the country: no artist of originality made lettering his special field or made any important contribution to formal lettering or type design in Britain until William Morris, aided by Emery Walker, founded the Kelmscott Press in 1891 (McLean 1963, p 62). McLean may not have thought the lettering found on music sheet covers of enough import to consider how they the work of Noel Humphreys and Owen Jones could have been influenced their lettering. The Rustic letters of the Nineteenth century, though, are certainly linked with a popular interest in medieval illumination, and therefore with the Victorian books that dealt with the subject. Rustic lettering, whether freely drawn or made into type, appears throughout the whole of the century. A style that continues for such a long period of time should not be brushed aside without some investigation. In fact, McLean mentions one connection between popular music sheets and the more expensive books of antiquarian taste. John Brandard (1812-63), a lithographic artist who designed many music sheet covers, worked for the publisher Joseph Cundall on at least one occasion. Brandard provided the decorative borders for A Booke of Christmas Carols, published in 1845 (McLean 1963). Although the lettering was type, it shows that some artists working for music publishers were also involved with book publishing, and possibly exposure to the illuminated works of Owen Jones and Noel Humphreys. The illuminated books mentioned by McLean are gift books, commonly of verses from the Bible, with decoration either copied from or at least inspired by that found in medieval manuscripts. There were also the books whose designers wished to reproduce this medieval decoration and did so with varying degrees of fidelity, but with scholarly intentions (McLean 1963, p 61). Of the latter category there are books by Henry Shaw, Henry Noel Humphreys and Owen Jones. McLean provides the most concise description of each artists work. Henry Shawwas essentially a scholar and antiquarian; in all his works he was trying to portray accurately the arts of the past.

27

Owen Jones was a designer, concerned with utilizing the arts of the past in a scholarly way for the embellishment of the present. Noel Humphreyswas a popularizer, with an astonishing gift for absorbing the art of the illuminated manuscriptsand recreating out of them modern pages which were not direct copies yet were full of vitality and richness (McLean 1963, p 62). It is about the fourth decade of the Nineteenth century that chromolithographed books of medieval illumination begin to appear in England, and it is about this time that alphabets formed from vegetation, trees or sticks of wood, such as the rustic typefaces, begin to appear. In Noel Humphreys The Poets Pleasaunce (1847) there are initial capitals which carry the natural scenery of flowers, sticks and insects found in the borders into the text. The initial caps are made of the same sticks and leaves found in the border, and even connect or grow out of those in the border. There are numerous

4.2. J. Pridham, Yorkshire bells (London: c. 1875). Lithograph [London: Brewer & Co].

4.1. C.H.R. Mariot, Champagne Charlie galop (London: c. 1870). Colour lithograph [London: Siebe & Burnett]. 324 x 236 mm.

28

examples of this kind of lettering found in the illuminated gift books such as in The Miracles of Our Lord (1848), also by Humphreys, Floriated Ornament (1849) by A.W. Pugin, and the Victoria Psalter (1861) by Owen Jones. It is evident that the lettering of these Victorian artists influenced that used in the music title pages of their century. There are the most obvious rustic forms shown in chapter 2, but there are also the forms seen in figure 4.1. The lettering here is flat with bulbous growths that really do seem like knobs on an old gnarled tree. Figure 4.2 shows a detail from Yorkshire Bells (fig. 1.3). One word, not very prominent, yet it follows the same formula as the title lettering for Champagne Charlie, only now in monoline.

29

CONCLUSION After leaving the traditions formed by engravers working in copper and other metals for intaglio printing, lithographers have formed their own tradition of lettering that. Taking what was advantageous from engravers, lithographers have used their reproduction process to enrich the history of lettering. Victorian illustrators who experimented with lettering provided lithographers with a way to begin experimentation. The Rustic letters offered them an opportunity to see how the lithographic process could combine picture and word into one unit. Throughout the nineteenth century, ornamented typefaces have influenced, and been influenced by, the freely drawn lettering found in these music title pages. Lithography has helped to increase the variety of letterforms available to the graphic arts by encouraging experimentation. The lettering found on nineteenth music title pages, whether woven seamlessly into a picture, intertwined with ornament, or used as means of creative experiment itself offers a springboard for further experiment.

30

Fig. ii. H.J. Tinney, Fizz galop (London: 1870s). Colour lithograph [London: Hopwood & Cres] 252 x 349 mm.

31

BIBLIOGRAPHY Callingham, J. The painters and grainers handbook. a complete illustrated guide to painting, graining, distempering, sign-writing, gilding and glass embossing, with instructions for using the patent graining rollers, also specimens of alphabets. With numerous useful recipes for painters and decorators. 1871 Gray, N. Nineteenth century ornamented type & title pages Faber & Faber, London 1976 Gray, N. Lettering as drawing Oxford University Press, London 1971 Humphreys, C. & W. C. Smith Music publishing in the British Isles from the beginning until the middle of the ninteenth century Basil Blackwell, Oxford 1970 Imeson, W. E. Illustrated music-titles and their delineators. A handbook for collectors Printed for the author, London 1912 King, A. H. Some victorian illustrated music titles Penrose Annual Vol 46 pp43-5 1952 King, A. H. English pictorial music title-pages 18201885. Their style, evolution and importance The Library fifth series Vol iv no 4 pp 262-72 1950 McLean, R. Victorian book design & colour printing Faber & Faber, London 1963 Neighbor & Tyson English music publishers plate numbers in the first half of the nineteenth century Faber & Faber, London 1965 Pearsall, R. Victorian sheet music covers David & Charles Limited, Newton Abbot 1972 Poole, H. E. A day at a music publishers: a description of the establishment or DAlmaine & Co. Journal of the Printing Historical Society no 14 pp 59-81 1979/80 Porzio, D., ed., Lithography 200 years of art history & technique. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1982 Ridler, V. Artistic printing: a search for principles Alphabet and image: 6 pp 4-17 January 1948

32

Spellman, D. & S. Victorian music covers Evelyn, Adams & Mackay, London 1969 Spellman collection of Victorian music covers 14 August 2003 <http: //vads.ahds.ac.uk> Twyman, M. Early lithographed books Farrand Press & Private Libraries Association, 1990. Early lithographed music Farrand Press, London 1996 Lithography 1800-1850 Oxford University Press, 1970. Printing 1770-1970 : an illustrated history of its development and uses in England The British Library, London 1998 Introduction The landscape alphabet Hurtwood Press, Silversted 1987 The Panizzi Lectures 2000. Breaking the mould: The first hundred years of lithography The British Library, London 2001 Weber, W. History of lithography. Thames & Hudson, 1966. Winter, M. H. Art score for music The Brooklyn Institute of Arts & Sciences, New York 1939

SOURCES FOR MUSIC TITLE PAGES University of Reading Library, Spellman collection of Victorian music covers digital archive, figures i, ii, 1.1, 1.2, 1.9, 1.12, 1.13, 1.15, 1.16, 1.18, 1.19, 2.2, 2.3, 2.6, 2.7, 2.8, 2.9ab, 2.11, 2.13, 2.14, 2.16ab, 2.17, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, 3.5, 3.7, 3.8, 4.1 Twyman, M., Private collection, figures 1.4a, 1.5, 1.6, 1.7, 1.8, 1.10, 1.11, 2.4, 2.5, 3.6 Blubaugh, B., Private collection, figures 1.3, 4.2

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Music As Propaganda in The German ReformationDocument10 paginiMusic As Propaganda in The German ReformationJulianna BousoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Goehr On Scruton AestheticsDocument13 paginiGoehr On Scruton AestheticsTom Dommisse100% (1)

- NeoRomanticism (Grove Online)Document3 paginiNeoRomanticism (Grove Online)EricÎncă nu există evaluări

- Visual Music & Poetry Art HistoryDocument19 paginiVisual Music & Poetry Art Historyapi-202535283Încă nu există evaluări

- Art in Print - Printed Bodies and The Materiality of Early Modern PrintsDocument5 paginiArt in Print - Printed Bodies and The Materiality of Early Modern PrintsAndrea TavaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Music and BoredomDocument7 paginiMusic and BoredomThomas PattesonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Minimalist Art vs. Modernist Sensibility - A Close Reading of Michael Fried's "Art and Objecthood" - Art & EducationDocument5 paginiMinimalist Art vs. Modernist Sensibility - A Close Reading of Michael Fried's "Art and Objecthood" - Art & EducationNoortje de LeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Futurist Manifestos Contents PDFDocument4 paginiFuturist Manifestos Contents PDFVal RavagliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Concrete Poetry in France After ApollinaireDocument12 paginiConcrete Poetry in France After Apollinaireapi-357156106Încă nu există evaluări

- Kenneth Goldsmith's Controversial Conceptual Poetry - The New YorkerDocument174 paginiKenneth Goldsmith's Controversial Conceptual Poetry - The New YorkerLeonello BazzurroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edgar VareseDocument4 paginiEdgar VareseJulio TorresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Auto Destructive Art Text RoutledgeDocument19 paginiAuto Destructive Art Text RoutledgePa To N'CoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lewis, George E. - Purposive Patterning - Jeff Donaldson, Muhal Richard Abrams, and The Multidominance of ConsciousnessDocument9 paginiLewis, George E. - Purposive Patterning - Jeff Donaldson, Muhal Richard Abrams, and The Multidominance of Consciousnessa100% (1)

- McCaffery and Nichol - Sound Poetry.a CatalogueDocument59 paginiMcCaffery and Nichol - Sound Poetry.a CatalogueChristoph CoxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jubert Cullars - Bauhaus Context Typography and Graphic Design in France PDFDocument16 paginiJubert Cullars - Bauhaus Context Typography and Graphic Design in France PDFhofelstÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mahler Conducted and Recorded From The Concert Hall To DVDDocument19 paginiMahler Conducted and Recorded From The Concert Hall To DVDJacksonÎncă nu există evaluări

- UniversDocument16 paginiUniversIngridChangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Typography: Typography Is The Art and Technique of Arranging Type To Make Written LanguageDocument12 paginiTypography: Typography Is The Art and Technique of Arranging Type To Make Written LanguageMaiara e maraiaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Composer in Interview: Giya KancheliDocument8 paginiComposer in Interview: Giya Kanchelitash0% (1)

- Baku Symphony of Sirens Sound Experiments in The Russian Avant-Garde PDFDocument77 paginiBaku Symphony of Sirens Sound Experiments in The Russian Avant-Garde PDFDámaris Vera100% (1)

- Art QuestionsDocument4 paginiArt QuestionsÉvaStósznéNagyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Pop Criticultural InfindibulatorDocument247 paginiThe Pop Criticultural InfindibulatorCarl JavierÎncă nu există evaluări

- Originality and Jones' The Grammar of Ornament of 1856 PDFDocument11 paginiOriginality and Jones' The Grammar of Ornament of 1856 PDFOliver Tolle100% (1)

- Design and WritingDocument3 paginiDesign and Writingmeghanwitzke7136Încă nu există evaluări

- Colonial MusicDocument39 paginiColonial MusicRobert J. SteelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ecstatic Alphabet MOMADocument44 paginiEcstatic Alphabet MOMArobertong81Încă nu există evaluări

- GROVE - Instrumentation and Orchestration PDFDocument14 paginiGROVE - Instrumentation and Orchestration PDFJoséArantes100% (2)

- Bring Da Noise A Brief Survey of Sound ArtDocument3 paginiBring Da Noise A Brief Survey of Sound ArtancutaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zaslaw - When Is An Orchestra Not An OrchestraDocument14 paginiZaslaw - When Is An Orchestra Not An OrchestraRodrigo Balaguer100% (1)

- Alexey Bro DovitchDocument21 paginiAlexey Bro DovitchJulie DeliopoulouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guide To Henry Cowell PapersDocument93 paginiGuide To Henry Cowell PapersOtalora2100% (1)

- 20th ComposersDocument12 pagini20th ComposersRamel OñateÎncă nu există evaluări

- B.Mus., Trinity College of Music, London, 2002 M.Mus., Distinction, Trinity College of Music, London, 2003Document79 paginiB.Mus., Trinity College of Music, London, 2002 M.Mus., Distinction, Trinity College of Music, London, 2003P ZÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wagner Letters To RockelDocument188 paginiWagner Letters To RockelAttila Attila Attila100% (2)

- Bob Dylan in Minnesota: Troubadour Tales from Duluth, Hibbing and DinkytownDe la EverandBob Dylan in Minnesota: Troubadour Tales from Duluth, Hibbing and DinkytownÎncă nu există evaluări

- Can Text Itself Become Music. Music-Text Relationships InNono's Composition of The Earlys 1960 - de BenedictisDocument25 paginiCan Text Itself Become Music. Music-Text Relationships InNono's Composition of The Earlys 1960 - de BenedictisMaría Marchiano100% (1)

- Press Release For Chromaphilia - The Story of Colour in Art by Stella PaulDocument2 paginiPress Release For Chromaphilia - The Story of Colour in Art by Stella PaulRocio Zamora100% (1)

- Music - Drastic or Gnostic?Document33 paginiMusic - Drastic or Gnostic?jrhee88Încă nu există evaluări

- Banding Together: How Communities Create Genres in Popular MusicDe la EverandBanding Together: How Communities Create Genres in Popular MusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chromaticism and Diatonicism in Beethoven's Waldstein SonataDocument9 paginiChromaticism and Diatonicism in Beethoven's Waldstein SonataLara PoeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Laird - Handbook of Literary RhetoricDocument3 paginiLaird - Handbook of Literary Rhetorica1765Încă nu există evaluări

- Michael KleinDocument43 paginiMichael KleinLaura CalabiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Caetano Veloso & David Byrne: Digital Booklet - Live at Carnegie HallDocument6 paginiCaetano Veloso & David Byrne: Digital Booklet - Live at Carnegie Hallmarcelo_souza_41Încă nu există evaluări

- Pre RaphaelitesDocument19 paginiPre RaphaelitesVishnu Ronaldus Narayan100% (3)

- Concrete Poetry and Conceptual ArtDocument21 paginiConcrete Poetry and Conceptual Artjohndsmith22Încă nu există evaluări

- Anselm KieferDocument9 paginiAnselm KieferdnzblkÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Abstract About The Art of Music - K. L. Walton (1988)Document15 paginiWhat Is Abstract About The Art of Music - K. L. Walton (1988)vladvaideanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artist Interview: Ryoji Ikeda, Creator of Superposition - UMS LobbyDocument4 paginiArtist Interview: Ryoji Ikeda, Creator of Superposition - UMS LobbyBerk ÖzdemirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Type Design BibliographyDocument3 paginiType Design BibliographyMarcelo SapoznikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ecstatic Alphabets MoMA Hoptman PDFDocument44 paginiEcstatic Alphabets MoMA Hoptman PDFSMMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Musical Symbolism in The Operas of Debussy and Bartok (Antokoletz)Document361 paginiMusical Symbolism in The Operas of Debussy and Bartok (Antokoletz)Nachinsky von Frieden100% (2)

- Picabia, Francis - Between Music and The Machine (Rothman)Document15 paginiPicabia, Francis - Between Music and The Machine (Rothman)Κωνσταντινος ΖησηςÎncă nu există evaluări

- A151 First Semester Session 2015/2016: Vsmf2031 Orchestra Iii Group BDocument36 paginiA151 First Semester Session 2015/2016: Vsmf2031 Orchestra Iii Group BJennyne Peipei100% (1)

- Thebes of The Seven GatesDocument33 paginiThebes of The Seven Gatesccampo44Încă nu există evaluări

- Visual Music DewittDocument9 paginiVisual Music DewittrioporcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Igor Stravinsky: Most Original and Influential Composer of The 20Th CenturyDocument14 paginiIgor Stravinsky: Most Original and Influential Composer of The 20Th CenturyFrancine TutaanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Color EducationDocument2 paginiColor EducationIngrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Color Wonderful The Revolutionary Color 1 Associates Wardrobe A PDFDocument252 paginiColor Wonderful The Revolutionary Color 1 Associates Wardrobe A PDFIngrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Color, The Faber Birren Book Collection PDFDocument33 paginiOn Color, The Faber Birren Book Collection PDFIngrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Representing Colors As Three Numbers: Maureen C. StoneDocument8 paginiRepresenting Colors As Three Numbers: Maureen C. StoneIngrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Call For Contributed Scientific Papers S PDFDocument2 paginiCall For Contributed Scientific Papers S PDFIngrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- CASE STUDY - Linear Light Fittings 2Document12 paginiCASE STUDY - Linear Light Fittings 2Ingrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- (1967) Finley - Turner Experiment With Colour TheoryDocument12 pagini(1967) Finley - Turner Experiment With Colour TheoryIngrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cube User GuideDocument17 paginiCube User GuideIngrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Application of The Munsell Color System To The Graphic ArtsDocument5 paginiThe Application of The Munsell Color System To The Graphic ArtsIngrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cube User GuideDocument17 paginiCube User GuideIngrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Linda M. Shires On Color Theory 1835 George Fields Emchromatographyem PDFDocument10 paginiLinda M. Shires On Color Theory 1835 George Fields Emchromatographyem PDFIngrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research On Color in Architecture and Environmental Design: Brief History, Current Developments, and Possible FutureDocument14 paginiResearch On Color in Architecture and Environmental Design: Brief History, Current Developments, and Possible FutureIngrid Calvo Ivanovic100% (1)

- (1855) William Page - The Art of The Use of Color in Imitation in Painting No. 1Document2 pagini(1855) William Page - The Art of The Use of Color in Imitation in Painting No. 1Ingrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Goethe Color TrianglesDocument1 paginăGoethe Color TrianglesIngrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Balancing Typeface Legibility and EconomyDocument14 paginiBalancing Typeface Legibility and EconomyIngrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Caligraphic TendenciesDocument62 paginiCaligraphic TendenciesIngrid Calvo Ivanovic100% (1)

- Dolly: Jij Bent Niet Mijn Baas, Maar Mijn Duivel Die Mijn Korte Leven Tot Een Hel Maakt!Document8 paginiDolly: Jij Bent Niet Mijn Baas, Maar Mijn Duivel Die Mijn Korte Leven Tot Een Hel Maakt!Ingrid Calvo IvanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project Camelot David Wilcock (The Road To Ascension) 2007 Transcript - Part 1Document19 paginiProject Camelot David Wilcock (The Road To Ascension) 2007 Transcript - Part 1phasevmeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 4 Fashion CentersDocument48 paginiChapter 4 Fashion CentersJaswant Singh100% (1)

- Lite Central VisayasDocument4 paginiLite Central VisayasBianca Gaitan100% (4)

- Springer Lecture Notes in Computer ScienceDocument2 paginiSpringer Lecture Notes in Computer ScienceIulica IzmanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uta Heinecke CV English 2pages - KopieDocument2 paginiUta Heinecke CV English 2pages - KopierusticityÎncă nu există evaluări

- SR20DET Engine Swap GuideDocument10 paginiSR20DET Engine Swap GuideJeff KentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unhomework - Unit 1Document1 paginăUnhomework - Unit 1api-266874664Încă nu există evaluări

- Perfume Attars and Their HistoryDocument6 paginiPerfume Attars and Their Historykiez3b79ju100% (1)

- Albinoni Adagio G-Minor Quartet SAMPLEDocument2 paginiAlbinoni Adagio G-Minor Quartet SAMPLEKylt Lestorn100% (1)

- Vocabulary O Level - TEST 46-60Document15 paginiVocabulary O Level - TEST 46-60Giok ZaimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maurice Lacroix 2010Document48 paginiMaurice Lacroix 2010Chaisee KoolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lista EurodanceDocument8 paginiLista EurodanceNelson van RoinujÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book Review - Doctrine of God by John FrameDocument3 paginiBook Review - Doctrine of God by John FrameJ. Daniel Spratlin100% (1)

- Ivy League VestDocument4 paginiIvy League VestNoémia100% (2)

- Dayna Kriger - Graphic Design PortfolioDocument31 paginiDayna Kriger - Graphic Design PortfolioDayna TeitelbaumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Red Queen by Victoria Aveyard ExtractDocument53 paginiRed Queen by Victoria Aveyard ExtractOrion Publishing Group85% (20)

- The One Ring - Loremasters Screen PDFDocument5 paginiThe One Ring - Loremasters Screen PDFtcnbagginsÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Majorship 1Document40 paginiEnglish Majorship 1Arjie DiamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gestion Practica Tareas Taller Lección Proyecto Total Examen No. Nombre/Apellido Gestión FormativaDocument1 paginăGestion Practica Tareas Taller Lección Proyecto Total Examen No. Nombre/Apellido Gestión FormativaAlexander MartinezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clarinet SongsDocument5 paginiClarinet SongsJose Claudio da Silva100% (1)

- P Et B FinalDocument207 paginiP Et B FinalzallpallÎncă nu există evaluări

- Food Revolution Day LyricsDocument1 paginăFood Revolution Day LyricsMaría Laura PonzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pen Shading Techniques Cheat Sheet - Shirish DeshpandeDocument14 paginiPen Shading Techniques Cheat Sheet - Shirish DeshpandeYitzak ShamirÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7 Section (Ceiling) : Architectural Design Position: Architect PRC No.: 0018676 PTR No.: 8941423 TIN No.: 907-359-364Document1 pagină7 Section (Ceiling) : Architectural Design Position: Architect PRC No.: 0018676 PTR No.: 8941423 TIN No.: 907-359-364John Bryan AguileraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anastasia Vassiliou. Argos From The Ninth To Fifteenth Centuries PDFDocument28 paginiAnastasia Vassiliou. Argos From The Ninth To Fifteenth Centuries PDFMauraAlbinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jeopardy Powerpoint TemplateDocument31 paginiJeopardy Powerpoint TemplatetpsbelleÎncă nu există evaluări

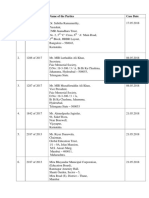

- S.No. Case No. Name of The Parties Case Date: RD TH NDDocument4 paginiS.No. Case No. Name of The Parties Case Date: RD TH NDAasim Ahmed ShaikhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Buehler Summet, Sample Prep and AnalysisDocument136 paginiBuehler Summet, Sample Prep and AnalysisSebastian RiañoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Work of ArchDocument5 paginiWork of ArchMadhu SekarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Charles Bukowski - WikipediaDocument82 paginiCharles Bukowski - WikipediaJulietteÎncă nu există evaluări