Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Anaphylaxis Clinical Presentation

Încărcat de

ilhampaneja_x3Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Anaphylaxis Clinical Presentation

Încărcat de

ilhampaneja_x3Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

4/9/2014

Anaphylaxis Clinical Presentation

Today News Reference Education Log Out My Account I Pane Discussion

Anaphylaxis Clinical Presentation

Author: S Shahzad Mustafa, MD; Chief Editor: Michael A Kaliner, MD more... Updated: Mar 20, 2014

History

Anaphylaxis is an acute multiorgan system reaction. The most common organ systems involved include the cutaneous, respiratory, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal (GI) systems. In most studies, the frequency of signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis is grouped by organ system. Anaphylactic reactions almost always involve the skin or mucous membranes. Greater than 90% of patients have some combination of urticaria, erythema, pruritus, or angioedema. In the Memphis study, for example, 87% of patients had urticaria and/or angioedema.[30] Other retrospective studies have reported similar rates of mucocutaneous involvement. Children, however, may be different. An Australian study evaluated 57 children under age 16 years who presented to a pediatric emergency department (ED) over a three-year period. Cutaneous features were noted in 82.5%, whereas 95% had respiratory symptoms. The reasons why a lack of dermal findings would be more common in children than in adults are not well understood. The upper respiratory tract commonly is involved, with complaints of nasal congestion, sneezing, or coryza. Cough, hoarseness, or a sensation of tightness in the throat may presage significant airway obstruction. Eyes may itch and tearing may be noted. Conjunctival injection may occur. Dyspnea is present when patients have bronchospasm or upper airway edema. Hypoxia and hypotension may cause weakness, dizziness, or syncope. Chest pain may occur due to bronchospasm or myocardial ischemia A ds by Keep N ow A d O ptions (secondary to hypotension and hypoxia). GI symptoms of cramplike abdominal pain with nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea also occur but are less common, except in the case of food allergy. The Memphis study reported dyspnea in 59%, syncope or lightheadedness in 33%, and diarrhea or abdominal cramps in 29%.[30] Other studies have reported similar findings. Initially, patients often describe a sense of impending doom, accompanied by pruritus and flushing. This can evolve rapidly into the following symptoms, broken down by organ system: Cutaneous/ocular - Flushing, urticaria, angioedema, cutaneous and/or conjunctival pruritus, warmth, and swelling Respiratory - Nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, throat tightness, wheezing, shortness of breath, cough, hoarseness Cardiovascular - Dizziness, weakness, syncope, chest pain, palpitations Gastrointestinal - Dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, bloating, cramps Neurologic - Headache, dizziness, blurred vision, and seizure (very rare and often associated with hypotension) Other - Metallic taste, feeling of impending doom Symptoms usually begin within 5-30 minutes from the time the culprit antigen is injected but can occur within seconds. If the antigen is ingested, symptoms usually occur within minutes to 2 hours. In rare cases, symptoms

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/135065-clinical 1/9

4/9/2014

Anaphylaxis Clinical Presentation

can be delayed in onset for several hours. Parenteral administration of monoclonal antibodies and oral ingestion of mammalian meat (eg, beef, pork, lamb) have recently been reported to be potential causes for anaphylaxis characterized by delayed onset.[53, 54, 55, 56, 57] It must be remembered that anaphylaxis can begin with relatively minor cutaneous symptoms and rapidly progress to life-threatening respiratory or cardiovascular manifestations. In general, the more rapidly anaphylaxis develops after exposure to an offending stimulus, the more likely the reaction is to be severe. A thorough history remains the best test to determine a causative agent. For recurrent idiopathic episodes, a patient diary may be helpful to implicate specific foods or medications, including over-the-counter (OTC) products.

Physical Examination

The first priority in the physical examination should be to assess the patients airway, breathing, circulation, and adequacy of mentation (eg, alertness, orientation, coherence of thought). General appearance and vital signs vary according to the severity of the anaphylactic episode and the organ system(s) affected. Vital signs may be normal or significantly disordered with tachypnea, tachycardia, and/or hypotension. Patients commonly are restless due to severe pruritus from urticaria. Anxiety, tremor, and a sensation of cold may result from compensatory endogenous catecholamine release. Anxiety is common unless hypotension or hypoxia causes obtundation. Frank cardiovascular collapse or respiratory arrest may occur in severe cases.

Respiratory findings

Severe angioedema of the tongue and lips (as may occur with the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors) may obstruct airflow. Laryngeal edema may manifest as stridor or severe air hunger. Loss of voice, hoarseness, and/or dysphonia may occur. Bronchospasm, airway edema, and mucus hypersecretion may manifest as wheezing. In the surgical setting, increased pressure of ventilation can be the only manifestation of bronchospasm. Complete airway obstruction is the most common cause of death in anaphylaxis.

Cardiovascular findings

Tachycardia is present in one fourth of patients, usually as a compensatory response to reduced intravascular volume or to stress from compensatory catecholamine release. Bradycardia, in contrast, is more suggestive of a vasodepressor (vasovagal) reaction. Although tachycardia is the rule, bradycardia has also been observed in anaphylaxis (see Pathophysiology). Thus, bradycardia may not be as useful for distinguishing anaphylaxis from a vasodepressor reaction as was previously thought. Relative bradycardia (initial tachycardia followed by diminished heart rate despite worsening hypotension) has been reported previously in experimental settings of insect sting anaphylaxis, as well as in trauma patients.[7, 8, 58, 59,

60]

Hypotension (and resultant loss of consciousness) may be observed secondary to capillary leak, vasodilation, and hypoxic myocardial depression. Cardiovascular collapse and shock can occur immediately, without any other findings. This is an especially important consideration in the surgical setting. Because shock may develop without prominent skin manifestations or history of exposure, anaphylaxis is part of the differential diagnosis for patients who present with shock and no obvious cause.

Cognitive findings

If hypoperfusion or hypoxia occurs, it can cause altered mentation. The patient may exhibit a depressed level of consciousness or may be agitated and/or combative.

Cutaneous findings

The classic skin manifestation is urticaria (ie, hives). Urticaria can occur anywhere on the body, often localizing to the superficial dermal layers of the palms, soles, and inner thighs. Lesions are red and raised, and they sometimes have central blanching. Intense pruritus occurs with the lesions. Lesion borders are usually irregular and sizes vary markedly. Only a few small or large lesions may become confluent, forming giant urticaria. At times, the entire dermis is involved with diffuse erythema and edema.

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/135065-clinical 2/9

4/9/2014

Anaphylaxis Clinical Presentation

In a local reaction, lesions occur near the site of a cutaneous exposure (eg, insect bite). The involved area is erythematous, edematous, and pruritic. If only a local skin reaction (as opposed to generalized urticaria) is present, systemic manifestations (eg, respiratory distress) are less likely. Local reactions, even if severe, are not predictive of systemic anaphylaxis on reexposure. Angioedema (soft-tissue swelling) is also commonly observed. These lesions involve the deeper dermal layers of skin. It is usually nonpruritic and nonpitting. Common areas of involvement are the larynx, lips, eyelids, hands, feet, and genitalia. Generalized (whole-body) erythema (or flushing) without urticaria or angioedema is also occasionally observed. Cutaneous findings may be delayed or absent in rapidly progressive anaphylaxis.

Gastrointestinal findings

Vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal distension are frequently observed.

Complications

Complications from anaphylaxis are rare, and most patients completely recover. Myocardial ischemia may result from hypotension and hypoxia, particularly when underlying coronary artery disease exists. Ischemia or arrhythmias may result from treatment with pressors. Prolonged hypoxia also may cause brain injury. At times, a fall or other injury may occur when anaphylaxis leads to syncope. Respiratory failure from severe bronchospasm or laryngeal edema can cause hypoxia, which could lead to brain injury if prolonged.

Contributor Information and Disclosures

Author S Shahzad Mustafa, MD Physician in Allergy, Immunology, and Rheumatology, Rochester General Medical Group; Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry S Shahzad Mustafa, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology and Finger Lakes Allergy Society, Inc Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. Chief Editor Michael A Kaliner, MD Clinical Professor of Medicine, George Washington University School of Medicine; Chief, Section of Allergy and Immunology, Washington Hospital Center; Medical Director, Institute for Asthma and Allergy Michael A Kaliner, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology, American Association of Immunologists, American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, American Society for Clinical Investigation, American Thoracic Society, and Association of American Physicians Disclosure: Teva Honoraria Speaking and teaching; Meda Honoraria Speaking and teaching; genentech Honoraria Speaking and teaching; sunovian Consulting fee Consulting Additional Contributors Roy Alson, MD, PhD, FACEP, FAAEM Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine; Medical Director, Forsyth County EMS; Deputy Medical Advisor, North Carolina Office of EMS; Associate Medical Director, North Carolina Baptist AirCare Roy Alson, MD, PhD, FACEP, FAAEM is a member of the following medical societies: Air Medical Physician Association, American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, American Medical Association, National Association of EMS Physicians, North Carolina Medical Society, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, and World Association for Disaster and Emergency Medicine Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/135065-clinical 3/9

4/9/2014

Anaphylaxis Clinical Presentation

Stephen C Dreskin, MD, PhD Professor of Medicine, Departments of Internal Medicine, Director of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Practice, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center Stephen C Dreskin, MD, PhD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology, American Association for the Advancement of Science, American Association of Immunologists, American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, Clinical Immunology Society, and Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Disclosure: Genentech Consulting fee Consulting; American Health Insurance Plans Consulting fee Consulting; Johns Hopkins School of Public Health Consulting fee Consulting; Array BioPharma Consulting fee Consulting Stephen F Kemp, MD, FACP Professor of Medicine, Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Director of Allergy and Immunology Fellowship Program, Departments of Medicine and Pediatrics, Associate Director of Division of Clinical Immunology and Allergy, Department of Medicine, University of Mississippi Medical Center; Staff Physician and Consultant in Allergy and Immunology, Medical Service, G V (Sonny) Montgomery Veterans Affairs Medical Center Stephen F Kemp, MD, FACP is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology, American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, American College of Physicians, Association of Subspecialty Professors, Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, Mississippi State Medical Association, and Southern Society for Clinical Investigation Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. Richard S Krause, MD Senior Clinical Faculty/Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Buffalo State University of New York School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences Richard S Krause, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. G William Palmer, MD Consulting Staff, Shoreline Allergy and Asthma Associates G William Palmer, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. Matthew M Rice, MD, JD, FACEP Senior Vice President, Chief Medical Officer, Northwest Emergency Physicians of TeamHealth; Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine Matthew M Rice, MD, JD, FACEP is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency Physicians, American Medical Association, National Association of EMS Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, and Washington State Medical Association Disclosure: Team Health Salary Employment Erik D Schraga, MD Staff Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, Mills-Peninsula Emergency Medical Associates Disclosure: Nothing to disclose. Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference Disclosure: Medscape Salary Employment

References

1. Kemp SF, Lockey RF. Anaphylaxis: a review of causes and mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Sep 2002;110(3):341-8. [Medline].

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/135065-clinical 4/9

4/9/2014

Anaphylaxis Clinical Presentation

2. Simons FE. Anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Feb 2008;121(2 Suppl):S402-7; quiz S420. [Medline]. 3. Braganza SC, Acworth JP, Mckinnon DR, Peake JE, Brown AF. Paediatric emergency department anaphylaxis: different patterns from adults. Arch Dis Child. Feb 2006;91(2):159-63. [Medline]. [Full Text]. 4. Alrasbi M, Sheikh A. Comparison of international guidelines for the emergency medical management of anaphylaxis. Allergy. Aug 2007;62(8):838-41. [Medline]. 5. Johansson SG, Bieber T, Dahl R, Friedmann PS, Lanier BQ, Lockey RF, et al. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol. May 2004;113(5):832-6. [Medline]. 6. Finkelman FD. Anaphylaxis: lessons from mouse models. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Sep 2007;120(3):50615; quiz 516-7. [Medline]. 7. Schadt JC, Ludbrook J. Hemodynamic and neurohumoral responses to acute hypovolemia in conscious mammals. Am J Physiol. Feb 1991;260(2 Pt 2):H305-18. [Medline]. 8. Demetriades D, Chan LS, Bhasin P, Berne TV, Ramicone E, Huicochea F, et al. Relative bradycardia in patients with traumatic hypotension. J Trauma. Sep 1998;45(3):534-9. [Medline]. 9. Wang J, Sampson HA. Food anaphylaxis. Clin Exp Allergy. May 2007;37(5):651-60. [Medline]. 10. Osborne NJ, Koplin JJ, Martin PE, et al. Prevalence of challenge-proven IgE-mediated food allergy using population-based sampling and predetermined challenge criteria in infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Mar 2011;127(3):668-76.e1-2. [Medline]. 11. Hourihane JO'B, Kilburn SA, Nordlee JA, Hefle SL, Taylor SL, Warner JO. An evaluation of the sensitivity of subjects with peanut allergy to very low doses of peanut protein: a randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled food challenge study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Nov 1997;100(5):596-600. [Medline]. 12. Decker WW, Campbell RL, Manivannan V, et al. The etiology and incidence of anaphylaxis in Rochester, Minnesota: a report from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Dec 2008;122(6):1161-5. [Medline]. [Full Text]. 13. Greenhawt MJ, Li JT, Bernstein DI, et al. Administering influenza vaccine to egg allergic recipients: a focused practice parameter update. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. Jan 2011;106(1):11-6. [Medline]. 14. [Guideline] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wk ly Rep. Aug 26 2011;60(33):1128-32. [Medline]. 15. Ann S, Reisman RE. Risk of administering cephalosporin antibiotics to patients with histories of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. Feb 1995;74(2):167-70. [Medline]. 16. Daulat S, Solensky R, Earl HS, Casey W, Gruchalla RS. Safety of cephalosporin administration to patients with histories of penicillin allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Jun 2004;113(6):1220-2. [Medline]. 17. Lin RY. A perspective on penicillin allergy. Arch Intern Med. May 1992;152(5):930-7. [Medline]. 18. Pichichero ME. A review of evidence supporting the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation for prescribing cephalosporin antibiotics for penicillin-allergic patients. Pediatrics . Apr 2005;115(4):1048-57. [Medline]. 19. Mertes PM, Malinovsky JM, Jouffroy L, et al. Reducing the risk of anaphylaxis during anesthesia: 2011 updated guidelines for clinical practice. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2011;21(6):442-53. [Medline]. 20. Golden DB. Insect sting anaphylaxis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. May 2007;27(2):261-72, vii. [Medline]. [Full Text]. 21. Amin HS, Liss GM, Bernstein DI. Evaluation of near-fatal reactions to allergen immunotherapy injections. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Jan 2006;117(1):169-75. [Medline]. 22. Bernstein DI, Wanner M, Borish L, Liss GM. Twelve-year survey of fatal reactions to allergen injections and skin testing: 1990-2001. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Jun 2004;113(6):1129-36. [Medline].

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/135065-clinical 5/9

4/9/2014

Anaphylaxis Clinical Presentation

23. Lockey RF, Benedict LM, Turkeltaub PC, Bukantz SC. Fatalities from immunotherapy (IT) and skin testing (ST). J Allergy Clin Immunol. Apr 1987;79(4):660-77. [Medline]. 24. Greenberger PA. Idiopathic anaphylaxis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. May 2007;27(2):273-93, vii-viii. [Medline]. 25. Meggs WJ, Pescovitz OH, Metcalfe D, Loriaux DL, Cutler G Jr, Kaliner M. Progesterone sensitivity as a cause of recurrent anaphylaxis. N Engl J Med. Nov 8 1984;311(19):1236-8. [Medline]. 26. Slater JE, Raphael G, Cutler GB Jr, Loriaux DL, Meggs WJ, Kaliner M. Recurrent anaphylaxis in menstruating women: treatment with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist--a preliminary report. Obstet Gynecol. Oct 1987;70(4):542-6. [Medline]. 27. Lieberman P. Anaphylaxis. In: Adkinson NF Jr, Bochner BS, Busse, WW, Holgate ST, Lemanske RF Jr, Simons FER, eds. Middleton's Allergy: Principles and Practice. 7th. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2009:1027-49. 28. Stark BJ, Sullivan TJ. Biphasic and protracted anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Jul 1986;78(1 Pt 1):76-83. [Medline]. 29. Sampson HA, Mendelson L, Rosen JP. Fatal and near-fatal anaphylactic reactions to food in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. Aug 6 1992;327(6):380-4. [Medline]. 30. Webb LM, Lieberman P. Anaphylaxis: a review of 601 cases. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. Jul 2006;97(1):39-43. [Medline]. 31. Boggs W. Anaphylaxis worse with antihypertensive medication. Medscape Medical News. March 21, 2013. Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/781274. Accessed April 2, 2013. 32. Lee S, Hess EP, Nestler DM, Bellamkonda Athmaram VR, Bellolio MF, Decker WW, et al. Antihypertensive medication use is associated with increased organ system involvement and hospitalization in emergency department patients with anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Apr 2013;131(4):1103-8. [Medline]. 33. Lieberman P. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. Aug 2008;8(4):316-20. [Medline]. 34. Neugut AI, Ghatak AT, Miller RL. Anaphylaxis in the United States: an investigation into its epidemiology. Arch Intern Med. Jan 8 2001;161(1):15-21. [Medline]. 35. Bresser H, Sandner CH, Rakoski J. Anaphylactic emergencies in Munich in 1992 (abstract). J Allergy Clin Immunol. Jan 1995;95:368. 36. Mertes PM, Laxenaire MC, Alla F. Anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions occurring during anesthesia in France in 1999-2000. Anesthesiology. Sep 2003;99(3):536-45. [Medline]. 37. Simons FE, Sampson HA. Anaphylaxis epidemic: fact or fiction?. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Dec 2008;122(6):1166-8. [Medline]. 38. Simons FE, Peterson S, Black CD. Epinephrine dispensing patterns for an out-of-hospital population: a novel approach to studying the epidemiology of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Oct 2002;110(4):647-51. [Medline]. 39. Moneret-Vautrin DA, Morisset M, Flabbee J, Beaudouin E, Kanny G. Epidemiology of life-threatening and lethal anaphylaxis: a review. Allergy. Apr 2005;60(4):443-51. [Medline]. 40. Bock SA, Muoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Fatalities due to anaphylactic reactions to foods. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Jan 2001;107(1):191-3. [Medline]. 41. Greenberger PA, Rotskoff BD, Lifschultz B. Fatal anaphylaxis: postmortem findings and associated comorbid diseases. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. Mar 2007;98(3):252-7. [Medline]. 42. Shehadi WH. Adverse reactions to intravascularly administered contrast media. A comprehensive study based on a prospective survey. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. May 1975;124(1):145-52. [Medline].

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/135065-clinical 6/9

4/9/2014

Anaphylaxis Clinical Presentation

43. Katayama H, Yamaguchi K, Kozuka T, Takashima T, Seez P, Matsuura K. Adverse reactions to ionic and nonionic contrast media. A report from the Japanese Committee on the Safety of Contrast Media. Radiology. Jun 1990;175(3):621-8. [Medline]. 44. Greenberger PA, Patterson R. The prevention of immediate generalized reactions to radiocontrast media in high-risk patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Apr 1991;87(4):867-72. [Medline]. 45. Pumphrey RS. Fatal posture in anaphylactic shock. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Aug 2003;112(2):451-2. [Medline]. 46. Demuth KA, Fitzpatrick AM. Epinephrine autoinjector availability among children with food allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc . Jul 2011;32(4):295-300. [Medline]. 47. [Guideline] Golden DB, Moffitt J, Nicklas RA, Freeman T, Graft DF, Reisman RE, et al. Stinging insect hypersensitivity: a practice parameter update 2011. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Apr 2011;127(4):852-4.e1-23. [Medline]. 48. Lieberman P, Nicklas RA, Oppenheimer J, et al. The diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis practice parameter: 2010 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Sep 2010;126(3):477-80.e1-42. [Medline]. 49. [Guideline] Simons FE, Ardusso LR, Bil MB, El-Gamal YM, Ledford DK, Ring J, et al. World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guidelines: summary. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Mar 2011;127(3):587-93.e1-22. [Medline]. 50. Haymore BR, Carr WW, Frank WT. Anaphylaxis and epinephrine prescribing patterns in a military hospital: underutilization of the intramuscular route. Allergy Asthma Proc . Sep-Oct 2005;26(5):361-5. [Medline]. 51. Rosen JP. Empowering patients with a history of anaphylaxis to use an epinephrine autoinjector without fear. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. Sep 2006;97(3):418. [Medline]. 52. Soller L, Fragapane J, Ben-Shoshan M, et al. Possession of epinephrine auto-injectors by Canadians with food allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Aug 2011;128(2):426-8. [Medline]. 53. Cox L, Platts-Mills TA, Finegold I, Schwartz LB, Simons FE, Wallace DV. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Joint Task Force Report on omalizumab-associated anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Dec 2007;120(6):1373-7. [Medline]. 54. Limb SL, Starke PR, Lee CE, Chowdhury BA. Delayed onset and protracted progression of anaphylaxis after omalizumab administration in patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Dec 2007;120(6):137881. [Medline]. 55. Cheifetz A, Smedley M, Martin S, et al. The incidence and management of infusion reactions to infliximab: a large center experience. Am J Gastroenterol. Jun 2003;98(6):1315-24. [Medline]. 56. Stallmach A, Giese T, Schmidt C, Meuer SC, Zeuzem SS. Severe anaphylactic reaction to infliximab: successful treatment with adalimumab - report of a case. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. Jun 2004;16(6):627-30. [Medline]. 57. Commins SP, Platts-Mills TA. Anaphylaxis syndromes related to a new mammalian cross-reactive carbohydrate determinant. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Oct 2009;124(4):652-7. [Medline]. [Full Text]. 58. Smith PL, Kagey-Sobotka A, Bleecker ER, et al. Physiologic manifestations of human anaphylaxis. J Clin Invest. Nov 1980;66(5):1072-80. [Medline]. [Full Text]. 59. van der Linden PW, Struyvenberg A, Kraaijenhagen RJ, Hack CE, van der Zwan JK. Anaphylactic shock after insect-sting challenge in 138 persons with a previous insect-sting reaction. Ann Intern Med. Feb 1 1993;118(3):161-8. [Medline]. 60. Brown SG, Blackman KE, Stenlake V, Heddle RJ. Insect sting anaphylaxis; prospective evaluation of treatment with intravenous adrenaline and volume resuscitation. Emerg Med J . Mar 2004;21(2):149-54. [Medline]. [Full Text]. 61. Akin C. Anaphylaxis and mast cell disease: what is the risk?. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. Jan 2010;10(1):34-8. [Medline].

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/135065-clinical 7/9

4/9/2014

Anaphylaxis Clinical Presentation

62. Bonadonna P, Perbellini O, Passalacqua G, et al. Clonal mast cell disorders in patients with systemic reactions to Hymenoptera stings and increased serum tryptase levels. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Mar 2009;123(3):680-6. [Medline]. 63. Rueff F, Przybilla B, Bilo MB, et al. Predictors of severe systemic anaphylactic reactions in patients with Hymenoptera venom allergy: importance of baseline serum tryptase-a study of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology Interest Group on Insect Venom Hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Nov 2009;124(5):1047-54. [Medline]. 64. Lin RY, Schwartz LB, Curry A, Pesola GR, Knight RJ, Lee HS, et al. Histamine and tryptase levels in patients with acute allergic reactions: An emergency department-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Jul 2000;106(1 Pt 1):65-71. [Medline]. 65. Simons FE. Anaphylaxis pathogenesis and treatment. Allergy. Jul 2011;66 Suppl 95:31-4. [Medline]. 66. Vadas P, Gold M, Perelman B, et al. Platelet-activating factor, PAF acetylhydrolase, and severe anaphylaxis. N Engl J Med. Jan 3 2008;358(1):28-35. [Medline]. 67. [Guideline] Boyce JA, Assa'ad A, Burks AW, Jones SM, Sampson HA, Wood RA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Dec 2010;126(6 Suppl):S1-58. [Medline]. 68. Lieberman P. Use of epinephrine in the treatment of anaphylaxis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. Aug 2003;3(4):313-8. [Medline]. 69. Sampson HA, Muoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report--second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. Ann Emerg Med. Apr 2006;47(4):373-80. [Medline]. 70. Kemp SF, Lockey RF, Simons FE. Epinephrine: the drug of choice for anaphylaxis. A statement of the World Allergy Organization. Allergy. Aug 2008;63(8):1061-70. [Medline]. 71. Sheikh A, Shehata YA, Brown SG, Simons FE. Adrenaline for the treatment of anaphylaxis: cochrane systematic review. Allergy. Feb 2009;64(2):204-12. [Medline]. 72. Sheikh A, Ten Broek V, Brown SG, Simons FE. H1-antihistamines for the treatment of anaphylaxis: Cochrane systematic review. Allergy. Aug 2007;62(8):830-7. [Medline]. 73. Choo KJ, Simons E, Sheikh A. Glucocorticoids for the treatment of anaphylaxis: Cochrane systematic review. Allergy. Oct 2010;65(10):1205-11. [Medline]. 74. Thomas M, Crawford I. Best evidence topic report. Glucagon infusion in refractory anaphylactic shock in patients on beta-blockers. Emerg Med J . Apr 2005;22(4):272-3. [Medline]. [Full Text]. 75. Borish L, Tamir R, Rosenwasser LJ. Intravenous desensitization to beta-lactam antibiotics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Sep 1987;80(3 Pt 1):314-9. [Medline]. 76. Kemp SF. The post-anaphylaxis dilemma: how long is long enough to observe a patient after resolution of symptoms?. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. Mar 2008;8(1):45-8. [Medline]. 77. Simons FE. Anaphylaxis: evidence-based long-term risk reduction in the community. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. May 2007;27(2):231-48, vi-vii. [Medline]. 78. Nurmatov U, Worth A, Sheikh A. Anaphylaxis management plans for the acute and long-term management of anaphylaxis: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Aug 2008;122(2):353-61, 361.e1-3. [Medline]. 79. Choo K, Sheikh A. Action plans for the long-term management of anaphylaxis: systematic review of effectiveness. Clin Exp Allergy. Jul 2007;37(7):1090-4. [Medline]. 80. Johnson K. Antibiotics common cause of perioperative anaphylaxis. Medscape Medical News [serial online]. November 22, 2013;Accessed December 3, 2013. Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/814903.

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/135065-clinical 8/9

4/9/2014

Anaphylaxis Clinical Presentation

Medscape Reference 2011 WebMD, LLC

A ds by Keep N ow

A d O ptions

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/135065-clinical

9/9

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Nclex Review Uworld (6515)Document137 paginiNclex Review Uworld (6515)whereswaldo007yahooc88% (8)

- UW Qbank Step-3 MWDocument513 paginiUW Qbank Step-3 MWSukhdeep Singh86% (7)

- Case Study On Bronchial AsthmaDocument29 paginiCase Study On Bronchial Asthmamanny valenciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medicine in Brief: Name the Disease in Haiku, Tanka and ArtDe la EverandMedicine in Brief: Name the Disease in Haiku, Tanka and ArtEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- 05 x05 Standard Costing & Variance AnalysisDocument27 pagini05 x05 Standard Costing & Variance AnalysisMary April MasbangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 7 ExamDocument3 paginiGrade 7 ExamMikko GomezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoku AnafilaktikDocument16 paginiShoku AnafilaktikindeenikeÎncă nu există evaluări

- By Mayo Clinic StaffDocument5 paginiBy Mayo Clinic StaffTry Febriani SiregarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anaphylaxis: Differential Diagnoses & Workup Treatment & Medication Follow-UpDocument8 paginiAnaphylaxis: Differential Diagnoses & Workup Treatment & Medication Follow-UpIndadiah LestariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shock AnaphylaticDocument15 paginiShock AnaphylaticAvif PutraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essential Update: New Practice Parameters For ED Management of AnaphylaxisDocument18 paginiEssential Update: New Practice Parameters For ED Management of AnaphylaxisyanzwinerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Approach To Adult Patients With Acute DyspneaDocument21 paginiApproach To Adult Patients With Acute DyspneaCándida DíazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 4 1. Nallathambi, Aiswarya 2. Nagarajan, Venkateshwari 3. Narayanaswamy, Nithya 4. Nallagatla, Susmitha 5. Narra, Vindhya RaniDocument100 paginiGroup 4 1. Nallathambi, Aiswarya 2. Nagarajan, Venkateshwari 3. Narayanaswamy, Nithya 4. Nallagatla, Susmitha 5. Narra, Vindhya RaniAishwarya BharathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anaphylaxis Diagnosis and ManagementDocument10 paginiAnaphylaxis Diagnosis and Managementd dÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Care (Emergency Medicine) : HemothoraxDocument7 paginiCritical Care (Emergency Medicine) : HemothoraxOrlando PiñeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- I Can't Breathe': Assessment and Emergency Management of Acute DyspnoeaDocument6 paginiI Can't Breathe': Assessment and Emergency Management of Acute DyspnoeaDisa CoelhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- DyspneaDocument8 paginiDyspneaNabilla SyafrianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anaphylaxis - Cancer Therapy AdvisorDocument11 paginiAnaphylaxis - Cancer Therapy AdvisorMohammed GazoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Charles Maytum, Rochester, MinnDocument6 paginiCharles Maytum, Rochester, Minngopal08Încă nu există evaluări

- Asthma and CopdDocument44 paginiAsthma and CopdBeer Dilacshe100% (1)

- Diagnostic Evaluation of Dyspnea: PathophysiologyDocument6 paginiDiagnostic Evaluation of Dyspnea: PathophysiologySaya GantengÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anaphylaxis - 1Document12 paginiAnaphylaxis - 1Ronald WiradirnataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing Care Plan For Anaphylactic Shockwith A Primary NursingDocument11 paginiNursing Care Plan For Anaphylactic Shockwith A Primary NursingKenn Harl CieloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pachtinger2013 PDFDocument16 paginiPachtinger2013 PDFdpcamposhÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is AnaphylaxisDocument13 paginiWhat Is AnaphylaxisJohn SolivenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 20 Nursing Management Postoperative CareDocument7 paginiChapter 20 Nursing Management Postoperative Caredcrisostomo8010Încă nu există evaluări

- Anaphylaxis: Diagnosis and Management: Mja Practice Essentials - AllergyDocument7 paginiAnaphylaxis: Diagnosis and Management: Mja Practice Essentials - AllergyFran ramos ortegaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asthma Thesis TopicsDocument5 paginiAsthma Thesis Topicsgjfcp5jb100% (1)

- Anaphylaxis: Diagnosis and Management: The Medical Journal of Australia October 2006Document8 paginiAnaphylaxis: Diagnosis and Management: The Medical Journal of Australia October 2006DidiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wolf-Hirschhorn SyndromeDocument7 paginiWolf-Hirschhorn SyndromeJulio AltamiranoÎncă nu există evaluări

- NEONATAL APNOEA SMNRDocument18 paginiNEONATAL APNOEA SMNRAswathy RC100% (1)

- Diagnostic Evaluation of DyspneaDocument7 paginiDiagnostic Evaluation of DyspneaMuchlissatus Lisa MedicalbookÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S0749070421000889 MainDocument17 pagini1 s2.0 S0749070421000889 MainEliseu AmaralÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Anaphylaxis Anaphylaxis Is A Life-Threatening TypeDocument9 pagini1 Anaphylaxis Anaphylaxis Is A Life-Threatening TypeCraigÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deteriorating PatientDocument39 paginiDeteriorating PatientDoc EddyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anaphylaxis: This Web Page Was Produced As An Assignment For An Undergraduate Course at Davidson CollegeDocument9 paginiAnaphylaxis: This Web Page Was Produced As An Assignment For An Undergraduate Course at Davidson CollegeBundhun SoobasschanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diseases and TreatmentsDocument72 paginiDiseases and TreatmentsJared Tristan LewisÎncă nu există evaluări

- RTM 3Document8 paginiRTM 3Christine Danica BiteraÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Treat: Septic ShockDocument6 paginiHow To Treat: Septic ShockmeeandsoeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Examen Fisico General IiDocument8 paginiExamen Fisico General IiLAURA DANIELA VERA BELTRANÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recognise Critical IllnessDocument4 paginiRecognise Critical IllnessRicky DepeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presenter - Dr. Ashray - VDocument33 paginiPresenter - Dr. Ashray - VKhushbu JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pediatric AnaphylaxisDocument19 paginiPediatric AnaphylaxisancillaagraynÎncă nu există evaluări

- Feline Asthma: A Pathophysiologic Basis of TherapyDocument5 paginiFeline Asthma: A Pathophysiologic Basis of TherapyEnnur NufianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Definition & Pathogenesis (Ngân) : Asthma - Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment 2015Document4 paginiDefinition & Pathogenesis (Ngân) : Asthma - Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment 2015everydayisagift9999Încă nu există evaluări

- ShockDocument34 paginiShockAnthon Kyle TropezadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anaphylactic Reaction: An Overview: Emergency MedicineDocument4 paginiAnaphylactic Reaction: An Overview: Emergency MedicinedoctorniravÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pleurisy WordDocument17 paginiPleurisy WordThoby MlelwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DispneuDocument9 paginiDispneuAfria Beny SafitriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stupor and Coma in AdultsDocument14 paginiStupor and Coma in AdultsElena Chitoiu100% (1)

- Respiratory System - 2019Document20 paginiRespiratory System - 2019Glen Lazarus100% (1)

- Geriatric Assessment (EDocFind - Com)Document32 paginiGeriatric Assessment (EDocFind - Com)Kristine Lou Khin WinÎncă nu există evaluări

- AtherosclerosisDocument7 paginiAtherosclerosisAna MarieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute Respiratory InfectionDocument28 paginiAcute Respiratory InfectionMazharÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cardiorespiratory Diseases of The Dog and Cat (VetBooks - Ir)Document371 paginiCardiorespiratory Diseases of The Dog and Cat (VetBooks - Ir)villindaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluationandtreatmentof Chroniccough: Genji Terasaki,, Douglas S. PaauwDocument13 paginiEvaluationandtreatmentof Chroniccough: Genji Terasaki,, Douglas S. PaauwRSU DUTA MULYAÎncă nu există evaluări

- CommaDocument18 paginiCommaMunna KendreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute Severe AsthmaDocument5 paginiAcute Severe AsthmaRizsa Aulia DanestyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Definition and Physiology: Upper Airway Cough Syndrome (Postnasal Drip Cough)Document2 paginiDefinition and Physiology: Upper Airway Cough Syndrome (Postnasal Drip Cough)غسن سمن المدنÎncă nu există evaluări

- Status AsmatikusDocument8 paginiStatus AsmatikusFebrianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topics For Oral Exam Thypoid FeverDrownTEFDocument2 paginiTopics For Oral Exam Thypoid FeverDrownTEFPCRMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Respiratory/Integumentary Student Learning OutcomesDocument7 paginiRespiratory/Integumentary Student Learning OutcomesKelsey WallaceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thermally Curable Polystyrene Via Click ChemistryDocument4 paginiThermally Curable Polystyrene Via Click ChemistryDanesh AzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation TemplateDocument3 paginiEvaluation Templateapi-308795752Încă nu există evaluări

- 1.technical Specifications (Piling)Document15 pagini1.technical Specifications (Piling)Kunal Panchal100% (2)

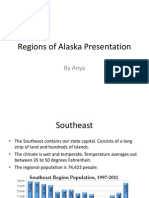

- Regions of Alaska PresentationDocument15 paginiRegions of Alaska Presentationapi-260890532Încă nu există evaluări

- Work ProblemsDocument19 paginiWork ProblemsOfelia DavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technical Specification For 33KV VCB BoardDocument7 paginiTechnical Specification For 33KV VCB BoardDipankar ChatterjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaDocument25 paginiDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaSumanth RoxtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science7 - q1 - Mod3 - Distinguishing Mixtures From Substances - v5Document25 paginiScience7 - q1 - Mod3 - Distinguishing Mixtures From Substances - v5Bella BalendresÎncă nu există evaluări

- OZO Player SDK User Guide 1.2.1Document16 paginiOZO Player SDK User Guide 1.2.1aryan9411Încă nu există evaluări

- Pt3 English Module 2018Document63 paginiPt3 English Module 2018Annie Abdul Rahman50% (4)

- CEE Annual Report 2018Document100 paginiCEE Annual Report 2018BusinessTech100% (1)

- Iec TR 61010-3-020-1999Document76 paginiIec TR 61010-3-020-1999Vasko MandilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deal Report Feb 14 - Apr 14Document26 paginiDeal Report Feb 14 - Apr 14BonviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Excon2019 ShowPreview02122019 PDFDocument492 paginiExcon2019 ShowPreview02122019 PDFSanjay KherÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5c3f1a8b262ec7a Ek PDFDocument5 pagini5c3f1a8b262ec7a Ek PDFIsmet HizyoluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson PlanDocument2 paginiLesson Plannicole rigonÎncă nu există evaluări

- LetrasDocument9 paginiLetrasMaricielo Angeline Vilca QuispeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 5 Designing and Developing Social AdvocacyDocument27 paginiLesson 5 Designing and Developing Social Advocacydaniel loberizÎncă nu există evaluări

- AlpaGasus: How To Train LLMs With Less Data and More AccuracyDocument6 paginiAlpaGasus: How To Train LLMs With Less Data and More AccuracyMy SocialÎncă nu există evaluări

- Obesity - The Health Time Bomb: ©LTPHN 2008Document36 paginiObesity - The Health Time Bomb: ©LTPHN 2008EVA PUTRANTO100% (2)

- Pavement Design1Document57 paginiPavement Design1Mobin AhmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jesus Prayer-JoinerDocument13 paginiJesus Prayer-Joinersleepknot_maggotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tplink Eap110 Qig EngDocument20 paginiTplink Eap110 Qig EngMaciejÎncă nu există evaluări

- BMOM5203 Full Version Study GuideDocument57 paginiBMOM5203 Full Version Study GuideZaid ChelseaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manual s10 PDFDocument402 paginiManual s10 PDFLibros18Încă nu există evaluări

- .Urp 203 Note 2022 - 1642405559000Document6 pagini.Urp 203 Note 2022 - 1642405559000Farouk SalehÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11-03 TB Value Chains and BPs - WolfDocument3 pagini11-03 TB Value Chains and BPs - WolfPrakash PandeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Howard R700X - SPL - INTDocument44 paginiHoward R700X - SPL - INTJozsefÎncă nu există evaluări