Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

2014 AIDSWatch HIV Criminalization Fact Sheet

Încărcat de

housingworksDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

2014 AIDSWatch HIV Criminalization Fact Sheet

Încărcat de

housingworksDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

HIV CRIMINALIZATION

A Challenge to Public Health and Ending AIDS

SUPPORT HR 1843, the Repeal HIV Discrimination Act of 2013, AND SUPPORT S 1790, the Repeal Existing Policies that Encourage and Allow Legal HIV Discrimination Act of 2013

What is HIV Criminalization?

HIV criminalization refers to the overly broad use of criminal law to penalize alleged, perceived or potential HIV exposure; alleged nondisclosure of a known HIV-positive status prior to sexual contact (including acts that do not risk HIV transmission); or nonintentional HIV transmission. Sentencing under HIV criminal law sometimes involves decades in prison or required sex offender registration, often in instances where no HIV transmission occurred or was even possible.

More than 1,000 people living with HIV have faced criminal charges in 39 states for allegedly exposing others or not disclosing their HIV-positive status.1 Thirty-three states (and two U.S. territories) have HIV-specific statutes,2 which apply only to people living with HIVan immutable characteristic. Prosecution is limited to those who know their HIV status, as those unaware of their HIV-status cannot be prosecuted for nondisclosure. HIV criminal laws often are based on long-outdated and inaccurate beliefs about HIV transmission risks rather than real science. Such laws further perpetuate misperceptions about HIV-risk and transmission and increase stigma against people living with HIV. By placing those who are aware of their HIV-positive status at increased risk of prosecution, HIV criminal laws contradict public health goals seeking to expand HIV testing and engagement in care and treatment.

APRIL 2829, 2014

HIV CRIMINAL LAWS OFTEN ARE BASED ON LONG-OUTDATED AND INACCURATE BELIEFS RATHER THAN REAL SCIENCE.

Consequences for People with HIV

HIV criminalization creates a disabling legal environment for people living with HIV,3 as well as an additional barrier to testing, treatment and disclosure of their HIV-positive status, putting them at heightened risk of vigilantism and violence.4 Even in instances when it has been demonstrated that HIV-positive individuals had an undetectable viral load (which has been shown to virtually eliminate the risk of transmission5) and used condoms, long sentences have not been unusual. Examples include sentences of 25 years in Iowa,6 30 years in Idaho7 and seven years in Michigan.8 Whats more, about 25% of recent criminalization cases were for biting, spitting or scratching.9 Despite the fact that those actions do not transmit HIV, the cases still resulted in disproportionately long sentencesfor example, a 35-year sentence in Texas10 and a 10-year sentence in New York.11 In addition, convicted individuals may be required to register as sex offenders.

HIV CRIMINALIZATION: A CHALLENGE TO PUBLIC HEALTH AND ENDING AIDS

Consequences for Public Health, Health Care Providers and Legal Services

HIV criminalization undermines public health efforts, challenges care for those living with HIV and puts undue burden on resource-constrained legal systems. Such laws: Punish responsible behaviorgetting testedand privilege ignorance regarding HIV status. Yet most new infections are transmitted by people who do not know they have HIV.12 Create mistrust of and lessen cooperation with traditional, effective public health initiatives, such as partner notification, and alienate people living with HIV from their health care providers.13

laws, policies, regulations, and judicial precedents and decisions regarding criminal and related civil commitment cases involving people living with HIV. Directs the AG to transmit to Congress and make publicly available the results of such review with related recommendations. Requires the AG and HHS Secretary to: 1) develop and publicly release guidance and best practice recommendations for states; and 2) establish an integrated monitoring and evaluation system to measure state progress. Directs the AG and HHS and DOD Secretaries to transmit to the President and Congress any proposals necessary to implement adjustments to federal laws, policies or regulations. Prohibits this Act from being construed to discourage the prosecution of individuals who intentionally transmit or attempt to transmit HIV to another individual. Does not have any fiscal ramifications.

Support HR 1843, the Repeal HIV Discrimination Act of 2013, and S 1790, the Repeal Existing Policies that Encourage and Allow Legal HIV Discrimination Act of 2013

Reps. Barbara Lee (D-Calif.) and Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-Fla.) introduced HR 1843 on May 7, 2013. The bill has 37 co-sponsors and has been referred to the House Committees on Judiciary, Energy and Commerce, and Armed Services. Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.) introduced similar legislation in the form of S 1790 on December 10, 2013, which has been referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee. We strongly urge co-sponsorship of these two bills. Congress must send a message that federal and state laws, policies, and regulations regarding people living with HIV should: Not place unique or undue burdens on individuals solely as a result of their HIV status. Demonstrate a public health-oriented, evidence-based, medically accurate, and up-to-date understanding of HIV transmission, health implications and treatment, as well as the negative impact of punitive HIV-specific laws, policies, regulations, and judicial precedents and decisions on public health and on affected people, families and communities. In particular, this critical legislation: Directs the U.S. Attorney General (AG), as well as the Secretaries of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Department of Defense (DOD), to initiate a national review of federal (including military) and state

1 Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+) and HIV Justice Network. Advancing HIV justice: a

progress report of achievements and challenges in global advocacy against HIV criminalisation. 2013. www.hivjustice.net/advancing/

2 Lehman JS, et al. Prevalence and public health implications of state laws that criminalize potential HIV

exposure in the United States. AIDS Behav. March 15, 2014. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10461-014-0724-0

3 Global Commission on HIV and the Law. Risk, rights and health. July 2012.

http://hivlawcommission.org/resources/report/FinalReport-Risks,Rights&Health-EN.pdf

4 The Sero Project. National criminalization survey. July 2012. www.seroproject.com 5 Rodger A, et al. HIV transmission risk through condomless sex if HIV+ partner on suppressive ART:

PARTNER study. 21st Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, 2014. Abstract 153LB.

6 State vs. Rhoades (Iowa 2010). 7 State vs. Thomas (Idaho 2009). 8 State vs. Merithew (Michigan 2013). 9 The Center for HIV Law and Policy. Spit does not transmit. March 2013. 10 State vs. Campbell (Texas 2008). 11 State vs. Plunkett (New York 2006).

www.hivlawandpolicy.org/resources/spit-does-not-transmit-center-hiv-law-and-policy-national-organization-black-law

12 The Center for HIV Law and Policy. What HIV Criminalization Means to Women in the U.S. February

2011. www.hivlawandpolicy.org/resources/what-hiv-criminalization-means-women-us-center-hiv-law-andpolicy-2011

13 OByrne P, et al. Nondisclosure prosecutions and population health outcomes: examining HIV testing,

HIV diagnoses, and the attitudes of men who have sex with men following nondisclosure prosecution media releases in Ottawa, Canada. BMC Public Health. February 2013. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/94

APRIL 2829, 2014

THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS: amfAR + AIDS Project Los Angeles + Bristol-Myers Squibb + Campaign to End AIDS + CommunityEducationGroup.org + fhi360 + Human Rights Campaign Foundation + International Association of Providers of AIDS Care + Legacy Community Health Services + National Minority AIDS Council + Pozitively Healthy

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Housing Works "What's Your Voting Plan?!" Sheet 2018Document1 paginăHousing Works "What's Your Voting Plan?!" Sheet 2018housingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Housing Works Get Out The Vote, Election Day 2018 Fact SheetDocument1 paginăHousing Works Get Out The Vote, Election Day 2018 Fact SheethousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2018 NYC LGBT March Route MapDocument1 pagină2018 NYC LGBT March Route MaphousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- End AIDS NY 2020 Coalition, World AIDS Day 2018 Resources ListingDocument3 paginiEnd AIDS NY 2020 Coalition, World AIDS Day 2018 Resources ListinghousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- New York State Ending The AIDS Epidemic Blueprint Summary One-SheetDocument2 paginiNew York State Ending The AIDS Epidemic Blueprint Summary One-SheethousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hillary Clinton Agenda and Meeting Notes 5.12.16Document9 paginiHillary Clinton Agenda and Meeting Notes 5.12.16Housing WorksÎncă nu există evaluări

- DOHMH Notes On Gov Exec Budget, 2.8.17Document2 paginiDOHMH Notes On Gov Exec Budget, 2.8.17housingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Housing Works April 2017 Town Hall Call-to-ActionDocument2 paginiHousing Works April 2017 Town Hall Call-to-ActionhousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- May 2016 AIDS Advocates Consensus Policy Paper W EndorsersDocument17 paginiMay 2016 AIDS Advocates Consensus Policy Paper W EndorsershousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Housing Works Get Out The Vote Election Day 2017Document1 paginăHousing Works Get Out The Vote Election Day 2017housingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civil Society and Communities Declaration To End HIV: Human Rights Must Come FirstDocument7 paginiCivil Society and Communities Declaration To End HIV: Human Rights Must Come FirsthousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- NYC LGBT Solidarity Rally Flyer For 2 4 17 ExternalDocument1 paginăNYC LGBT Solidarity Rally Flyer For 2 4 17 ExternalhousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- AIDS - Free USA 2025 Indiv Sign-On Petition For 2016 Prez Candidates (Download Copy)Document2 paginiAIDS - Free USA 2025 Indiv Sign-On Petition For 2016 Prez Candidates (Download Copy)housingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- #ICantBreathe/ Dec. 2014-Jan. 2015 Calls-to-Action Flyer, Housing Works Advocacy ActionsDocument2 pagini#ICantBreathe/ Dec. 2014-Jan. 2015 Calls-to-Action Flyer, Housing Works Advocacy ActionshousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nigerian LGBTers Invite To 1/12/15 Veil of Silence Doc ScreeningDocument1 paginăNigerian LGBTers Invite To 1/12/15 Veil of Silence Doc ScreeninghousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- NY State Trans Healthcare Regulation Dec. 2014Document4 paginiNY State Trans Healthcare Regulation Dec. 2014housingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Braking AIDS Ride 2014. 9/12-9/14, Cheering Stations GuideDocument1 paginăBraking AIDS Ride 2014. 9/12-9/14, Cheering Stations GuidehousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- NYC World AIDS Day 2015 Coalition Event SaveTheDate Flyer EnglishDocument1 paginăNYC World AIDS Day 2015 Coalition Event SaveTheDate Flyer EnglishhousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Housing Works Trans Day of Rememberance 2014 Event FlyerDocument1 paginăHousing Works Trans Day of Rememberance 2014 Event FlyerhousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Housing Works World AIDS Day 2014 CoalitionEvent FlyerSaveTheDate, EnglishDocument1 paginăHousing Works World AIDS Day 2014 CoalitionEvent FlyerSaveTheDate, EnglishhousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- NYC World AIDS Day Coalition Program, 12-1-14, Harlem's World Famous ApolloDocument4 paginiNYC World AIDS Day Coalition Program, 12-1-14, Harlem's World Famous ApollohousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Task Force End of AIDS NYS, Opening Remarks, 10.14.14, CKingDocument3 paginiTask Force End of AIDS NYS, Opening Remarks, 10.14.14, CKinghousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2014 IBJ JusticeMakers Award Applications LetterDocument2 pagini2014 IBJ JusticeMakers Award Applications LetterhousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Housing Works World AIDS Day 2014 CoalitionEvent FlyerSaveTheDate, SpanishDocument1 paginăHousing Works World AIDS Day 2014 CoalitionEvent FlyerSaveTheDate, SpanishhousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Media Advisory 10.27 AIDS Community Press Conf RE Cuomo Ebola Quarantine FINALDocument1 paginăMedia Advisory 10.27 AIDS Community Press Conf RE Cuomo Ebola Quarantine FINALhousingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Undetectables Project September 2014 2Document11 paginiUndetectables Project September 2014 2housingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quarantine - Leadership Letter FINAL 10 26 14Document6 paginiQuarantine - Leadership Letter FINAL 10 26 14housingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Harrison - Brooklyn ONAP Presentation 8.8.14Document15 paginiHarrison - Brooklyn ONAP Presentation 8.8.14housingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- O'Connell and Feldman - Manhattan ONAP Presentation 8.7.14Document9 paginiO'Connell and Feldman - Manhattan ONAP Presentation 8.7.14housingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Harrison - Brooklyn ONAP Presentation 8.8.14Document15 paginiHarrison - Brooklyn ONAP Presentation 8.8.14housingworksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Track - 1 - 28 - Essential Vocabulary For The TOEFL TestDocument39 paginiTrack - 1 - 28 - Essential Vocabulary For The TOEFL TestBountongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Calendar of Days & Awareness DaysDocument2 paginiCalendar of Days & Awareness DaysAshfaque HossainÎncă nu există evaluări

- PG StatementDocument6 paginiPG StatementDede RosadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aids EssayDocument6 paginiAids EssayReeni GrayÎncă nu există evaluări

- IntegumentaryDocument8 paginiIntegumentaryRamon Carlo AlmiranezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uts Chapter 2 Lesson 1Document29 paginiUts Chapter 2 Lesson 1John Jerome GironellaÎncă nu există evaluări

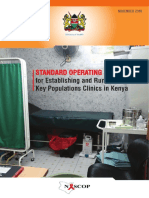

- STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES For Establishing and Running Key Populations Clinics in KenyaDocument40 paginiSTANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES For Establishing and Running Key Populations Clinics in KenyaElvisÎncă nu există evaluări

- One Step Anti-HIV (1&2) TestDocument4 paginiOne Step Anti-HIV (1&2) TestGail Ibanez100% (1)

- Final Proposal Based On CommentsDocument51 paginiFinal Proposal Based On CommentsWudu Sewmehon100% (1)

- Vaccines For HumansDocument176 paginiVaccines For HumansLisette Gamboa100% (1)

- Biology ProjectDocument52 paginiBiology ProjectBhagat Bhandari67% (3)

- Treatmentandpreventionof Acutehepatitisbvirus: Simone E. Dekker,, Ellen W. Green,, Joseph AhnDocument14 paginiTreatmentandpreventionof Acutehepatitisbvirus: Simone E. Dekker,, Ellen W. Green,, Joseph AhnSAMIA BOUNAOUESAJRÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paediatric ART Initiation and Follow UpDocument33 paginiPaediatric ART Initiation and Follow UpChetan AdsulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uas 2012Document6 paginiUas 2012ArdiSila DorkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Namibia Flipchart Algorithm Child Sep2010Document11 paginiNamibia Flipchart Algorithm Child Sep2010Gabriela Morante RuizÎncă nu există evaluări

- TanzaniaDocument10 paginiTanzaniahst939Încă nu există evaluări

- The LGBT Movements Health Issues - Higher Rates of HIV/AIDS and Other STDs Among LGBT MembersDocument127 paginiThe LGBT Movements Health Issues - Higher Rates of HIV/AIDS and Other STDs Among LGBT MembersAntonio BernardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Radical Philosophy 156 PDFDocument68 paginiRadical Philosophy 156 PDFkarlheinz1Încă nu există evaluări

- HIV-associated Lung DiseaseDocument18 paginiHIV-associated Lung Diseasedorlisa peñaÎncă nu există evaluări

- HIVR4P2018 - Abstract USB BookDocument450 paginiHIVR4P2018 - Abstract USB BookЛука ЈовановићÎncă nu există evaluări

- Life Skills A Facilitator Guide For Teenagers PDFDocument79 paginiLife Skills A Facilitator Guide For Teenagers PDFMonia AzevedoÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHILDLINE India FoundationDocument15 paginiCHILDLINE India FoundationBalajiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beyond Doing No HarmDocument12 paginiBeyond Doing No HarmIsidro ChucÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historical OVERVIEW On Blood BankingDocument4 paginiHistorical OVERVIEW On Blood BankingSogan, MaureenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 01Document23 paginiChapter 01SmileCaturas100% (1)

- CHN ExamDocument30 paginiCHN ExamKhei Laqui SN100% (3)

- CV Paul TeacherDocument3 paginiCV Paul Teachereloinkurunziza332Încă nu există evaluări

- Important Reports 2012-13Document14 paginiImportant Reports 2012-13Pavan VasanthamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Region Vii-Central Visayas Schools Division of Bohol: Music 10 Second Quarter Quarter: 2 Day 1 Activity No: 2Document8 paginiRegion Vii-Central Visayas Schools Division of Bohol: Music 10 Second Quarter Quarter: 2 Day 1 Activity No: 2Jess Anthony EfondoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cyflow Counter: The Complete Solution For Hiv/Aids MonitoringDocument12 paginiCyflow Counter: The Complete Solution For Hiv/Aids MonitoringDinesh SreedharanÎncă nu există evaluări