Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Beaney Fascination Antigone

Încărcat de

cgarriga2Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Beaney Fascination Antigone

Încărcat de

cgarriga2Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Opticon1826, Issue 7, Autumn 2009

BEAUTIFUL DEATH: THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY FASCINATION WITH ANTIGONE By Tara Beaney

Abstract This article investigates the reception of Sophocles Antigone in early nineteenth-century Germany, a period in which interest in ancient Greek tragedy flourished, with Antigone being particularly prominent. The essay considers two influential figures of the period who regarded the work highly: the philosopher G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831) and the poet Friedrich Hlderlin (17701843). In discussing their attitudes towards Antigone, the article raises the long-standing philosophical problem of how tragic representations of suffering and death, such as Antigones self-sacrifice, can arouse aesthetic pleasure and fascination. To address this problem, a sociohistorical approach is taken, exploring how the topos of female death may have appealed to the imagination of these important thinkers.

The story of Antigone has a peculiar persistence. Since Sophocles wrote the tragedy nearly two and a half thousand years ago, it has been repeatedly translated, adapted and interpreted, retaining its potential to captivate new audiences and readers. This phenomenon itself has attracted a wealth of critical studies, notably George Steiners Antigones (1984). Moreover, as any survey of critical interest in Antigone reveals, the story has been discussed in a wide range of discourses, from philosophy to politics to psychoanalysis and, more recently, feminism. In this article, my focus is on an intriguing confluence within the play, namely that of tragic death and femininity.1 I consider the reception of Antigone in Germany around the 1800s, when the tragedy was particularly popular, and I ask the question: to what extent was the fascination with this tragedy a fascination with Antigones death? Historys pre-eminent work of art As Steiner claims, the period from c.1790 to c.1905 saw Antigone widely proclaimed as a preeminent work of art (1984, 1). The philosopher G.W.F. Hegel stands out in having declared Antigone to be not only an excellent tragedy but one of the most sublime and most consummate works of art human effort has ever brought forth (Steiner 1984, 4). The poet Friedrich Hlderlin and the philosopher F.W.J. von Schelling, Hegels fellow students in Tbingen in the early 1890s, shared his admiration, participating in the propagation of an Antigone cult which persisted through the nineteenth century. In 1843, for example, the German playwright Friedrich Hebbel pronounced Antigone the masterpiece of all masterpieces; in 1846, the English essayist Thomas De Quincey wrote that the play towers into affecting grandeur like no other; and by 1869, the composer Richard Wagner had designated the play the incomparable par excellence (Steiner 1984, 4-5). However, there are some voices opposing this general picture of universal admiration painted by Steiner. A. W. Schlegel, for example, in his 1768-1803 lectures on dramatic art, voiced what he called the usual opinion, that Antigone (together with Ajax) is the poorest of Sophocles tragedies.

Readers interested in the literary study of representations of female death might see Elizabeth Bronfens Over Her Dead Body (1992). 1

Opticon1826, Issue 7, Autumn 2009

In this respect, he took issue with the way Antigone stretches out so long after the so-called catastrophe, the young womans death (1982, 200). For Hegel, and Hlderlin, however, as I will argue, the fact that Antigone dies so early on is no obstacle to the supremacy of the play. Moreover, the mere fact that the range of Sophocles plays was commonly known and critically discussed by those such as A.W. Schlegel is testimony to a dominant strain in the zeitgeist of early nineteenth-century Germany; namely the spirit of Hellenism. Hegel and Hlderlin were key figures in this movement, which propagated an interest in the arts and culture of classical Greece and Rome, and favoured literature in the style of German classicism, such as was adopted by two leading German writers, Goethe and Schiller, from the late 1780s to the early 1800s. And if Antigone was, to an extent, at the forefront of the Hellenic movement, then it will be worth investigating what caused this particular play to be brought forward into the public sphere, and to be widely performed, discussed and criticised.2 Closure and meaning through death To understand why Antigone was of particular interest to writers like Hegel and Hlderlin, I will turn to the major themes of the tragedy, the core of which is Antigones death. Her death pervades the play, as it is anticipated from the beginning, carried out in the middle, and followed by repercussions that establish the monumental significance of this young womans demise. Antigone raises the possibility of dying in the opening dialogue; by exhorting her sister to help bury their brother Polyneices, she opposes Creons rule and puts her own life at stake. Since she believes in proclaiming her deed aloud (ll.76)3 it cannot be long before Creon discovers that she has scattered earth over her brother, and sends her to be buried alive in a tomb. This is still only the middle of the play; the suicides of Creons son and wife, the consequences of the death sentence, have yet to be played out. Thus, Antigones death is thus not simply a tragic resolution to a plot relentlessly driving towards death (as with, say, Oedipus Tyrannus); rather, it is a vital element in the dramatic action, one which contributes to the overall cohesion and wider significance of the plot. Death is often given the role of providing a sense of closure in written narratives and theatrical performances, for it is an act of greater finality and completeness than any other. The role that death assumes in Antigone has become canonical in Western tradition; here, death poses the potential for imparting a concluding meaning to a completed life. Before Antigone is sent to her death she is given a long sung dialogue (kommos) of emotional intensity in the fourth episode, in which she reflects upon the teleology of her life cut short before marriage and the fulfilment of her womanhood. This moment, as well as imparting pathos, allows her life to become transmissible (Brooks 1992, 28). As Walter Benjamin put it, Death is the sanction of everything which the storyteller can tell (1977, 450, my translation); in other words, it is only through the finality of death that the overall shape and value of an individual life story can be determined. The idea of death as the supreme climax of life was especially popular amongst many German Romantics (such as Kleist and Novalis) in the late eighteenth century (Inwood 1992, 71). It is

2 The date that Steiner gives as the end of Antigones popularity signals Freuds choice to view Sophocles Oedipus as the central myth of Western culture. The recent rejection of this in psychoanalytic and feminist works (such as Lacan 1986 and Irigaray 1974) has encouraged a revival of critical engagement with Antigone, stimulating new debates on gender and kinship (such as Butler 2000) and articles devoted to the Antigone theme (for example as the focus of the Sept. 2008 Mosaic journal). 3 The references to Antigone refer to line numbers in the Cambridge translation by David Franklin.

Opticon1826, Issue 7, Autumn 2009

thus significant that Friedrich Schlegel, another key writer of the period, praised Sophocles play as being vollkommen- perfect or complete (Steiner 1984, 3). This elevated idea of completeness, which is made possible through death, also allows for a celebration of life, as indicated by Hegels attitude towards the actual death of his infant daughter; rather than feel any bitterness, Hegel remembers the joy of her birth (Houlgate 1998, 6). Unlike some previous philosophers (such as Parmenides and Spinoza), Hegel came to think of death as something imminent within any organism and which should be embraced as part of life (Houlgate, 16). The extensive influence of this idea might be traced through Nietzsche and into the twentieth century, with Rilkes poetic articulation of carrying death within us like the kernel of a fruit (1996 II, 459). Creon realises the significance of Antigones final lament, ordering her to be swiftly led away before she can fully impart her life with tragic meaning in the face of death. Her last words are ones of imploration: See what I suffer and at whose hands/ Because I respected reverence (ll.907-8). In asking the audience to realise her situation, Antigone brings us closer to the inevitability of our own deaths; such sensations of fear and pity are integral to tragedy, according to Aristotle (350BC, ch.9). By identifying with Antigone, we feel fear over what fate can bring, and pity for the victims of such a fate. It is important that the tragic events provide us with this insight, that the display of suffering does not appear completely senseless, for that would be at odds with the ideal of finding closure. To be moved by Antigones death is to be convinced that death imparts some higher meaning or serves some purpose. To understand the powerful response to the play, therefore, not only requires a consideration of tragic death, but also involves making sense of Antigones choice to sacrifice her life rather than leave her brother unburied. Sacrifice Antigone has long been associated with noble, heroic death, a death that is accepted rather than resisted. Antigone asserts that she has chosen to die (ll.519); she embraces her death, rather than merely submit to it passively. When she is sent to starve slowly in a tomb, she hangs herself instead, performing a final gesture of autonomy. For Hegel, this type of act came to signify a fundamental way of thinking about self-consciousness. In his Phenomenology of Spirit (1807), he writes that the most basic way for a subject to achieve recognition of their subjecthood is to show that they are prepared to sacrifice their existence as an object: it is only through staking ones life that freedom is won (1807, 113-4). Hegels thinking here is dialectic; he considers two subjects engaged in a life-and-death struggle to realise their subjecthood. Just as each stakes their own life, so too do they seek the others death, since the other is something which opposes their own status as subject. Hegels discussion on the central conflict of the play (in the Phenomenology of Spirit) follows the same lines, stressing the fundamental opposition between Creon and Antigone. This is suggested by their exchange, in the second episode, in which Antigone proclaims: There is nothing in your words that pleases me I pray it never will and what I say is just as displeasing to you. And yet how could I have won greater glory than by laying my own brother in his grave (ll.458-461). Antigone seeks recognition for her choice, but not from Creon, whose outlook is as rigid as hers here. In highlighting this conflict, Hegel was able to articulate what he saw (according to popular interpretations of his work) as the historical conflict challenging Greek ethical life at the time, namely that of the tension between individual and state. In his works, this conflict forms the basis of ethics, which he calls Sittlichkeit - custom or ethical substance. He divides this into divine and human laws which, in his interpretation of Antigone, are represented by Antigone and

3

Opticon1826, Issue 7, Autumn 2009

Creon respectively. Antigone thus upholds the law of the gods in her insistence on carrying out the funeral rites; she is further allied with the sphere of kinship, womankind and nature, whilst Creons stance derives from concerns with governing the state. The sense of antithesis between these two central characters in the play is brought out by the one-line exchanges (stichomythia) between Antigone and Creon. This is something which Hlderlin draws attention to in his discussion of the tragedy (in the notes to his poetic translation, Antigon): he calls these exchanges true murder by language, a linguistic articulation of irresolvable difference, which can culminate only in physical murder (1804, 788). Once the conflict has been set in place in this manner, it is possible, like Hegel, to see Antigone as a heroine of autonomy, striving to maintain her values and subjectivity in the face of opposing forces, and even sacrificing herself to realise her autonomy. However, Antigones act of sacrifice invites many further interpretations. For Hlderlin, who, like Hegel, supported the French Revolution, the play is clearly political, expressing vaterlndische Umkehr (disturbances in the fatherland) (1804, 789).4 Hlderlin uses words like Aufstand (uprising) in his translation (768), thereby writing the subtext of contemporary politics into the Greek play. For others, Antigones self-assertive sacrifice might have been allied with movements towards female emancipation, though Steiner (1984) claims that this notion was still only part of the idiom of the ideal at the time. For others, Antigones sacrifice may have recalled that of Christ: De Quincey, for example, saw Antigone in this way, referring to her as a daughter of God, before God was known (1845, 364). Whilst Antigones sacrifice can be regarded positively, as an emblem of some higher principle, it is also problematic, particularly with regards to the sisterly motivation for her act. Mathew Arnold (in 1853) famously said that a drama about sacrificing oneself in order to complete the burial of the brother is no longer one in which it is possible that we should feel a deep interest (Walsh 2008, 1). In the earlier, German context, Goethe, whilst praising Antigone as the most sisterly of souls (Steiner 1984, 12), was critical of a certain passage (ll.871-880) which became notorious in subsequent scholarship (Goldhill 2006, 158). This is the passage in which Antigone explains that she would be prepared to die for a brother, since with her parents dead, he becomes irreplaceable; yet she would not die for a husband or child, who could be replaced. There is still contention over whether these lines were part of Sophocles original text (or lines added by actors before Aristotles lifetime), yet they are significant in raising questions surrounding the values of kinship (Goldhill 2006, 158). This dispute underlies many of the conflicts in the interpretations of Antigone. Hlderlin, however, was happy to stress the sister-brother tie, translating the contentious passage as: Wenn aber Mutter/ Und Vater schlft, im Ort der Toten beides/ Stehts nicht als wchs ein anderer Bruder wieder But if mother/ and father sleep, both in the place of death / another brother could not grow again (768). Hlderlin introduces the imagery of nature here: the striking expression of the brother growing emphasises Antigones implication in the natural sphere, continuing on from the wasteland imagery which Hlderlins used for Antigones comparison of herself to Niobe (765). After such lexical associations, Antigones following assertion these are the laws by which I honoured you serves to implicate her in the sphere of natural law, as in Hegels interpretation. For Hlderlin, Antigones implication in the natural sphere is associated

All translations of Hlderlin are my own.

Opticon1826, Issue 7, Autumn 2009

with her unreflective, intuitive nature; she responds to Creons criticism of her act of honouring the brother who had attacked the state with what Hlderlin translates as Wer wei, da kann doch drunt ein andrer Brauch sein who knows, maybe theres another custom down there. For Hlderlin, as he writes in his own notes, Antigone is endearing and dreamily nave (784). It is her sisterly nature which he brings out with phrases such as the famous opening: Gemeinsamschwesterliches! an almost untranslatable adjectival monstrosity along the lines of oh common-sisterliness! (737). Verging on the border of the incomprehensible (and Hlderlin was to descend into madness after writing this work), the phrase does justice to the closeness of the bond between Antigone and her sister Ismene. The literalism of the following line in Hlderlin Oh Ismenes Haupt (oh body of Ismene) brings out the physical level of the Greek appellation (Ismns kara). Thus, in Hlderlins account, Antigones sacrifice is a tribute to her compassion and femininity. Death, marriage and crossing-over Sent to her death, Antigone finds a parallel in that other event which was of central, defining significance in a womans life at the time: marriage. She describes dying as a marriage to Achelon (one of the rivers in Hades), and, in this sense, views death as a transition in the same way as marriage would be, though one is a journey towards death as opposed to life. In this way, death becomes an act most properly belonging to the sphere of women. The self-sacrificial or suicidal nature of Antigones death is particularly associated with femininity; like Antigone, Creons wife also kills herself after hearing of her sons death. Steiner (1984) confirms this view, with the claim that antique sensibility attached an aura of the feminine to suicide (242). Although Creons son, Haemon (who was betrothed to Antigone) also stabs himself at the end of the play, he does so only after failing to strike his father, or, in other words, after a failure of masculine power. Haemon is also denigrated for his feminine associations earlier in the play, when Creon calls him lower than a woman (ll.693) and slave of a woman (ll.707). It is through suicide, therefore, that women, unable to kill their enemy, are able to seek male glory (which is what Antigone professes to seek in ll.460). Her act of self-sacrifice also links her to the fate of her brothers, who killed each other; autoktonounte is the word used for both Antigones death and the kin-murder of the brothers (Goldhill 2006, 152). This idea that death is an act epitomised by femininity finds resonances in the nineteenth-century context. De Quincey, who approved of Antigones spirit of martyrdom, writes: Yet sister woman[] you can do one thing as well as the best of us men[] you can die grandly, and as goddesses would die, were goddesses mortal (in Bronfen 1992, ii). Here death has become associated with sentimentalised feminine submissiveness. Hlderlins translation follows a similar spirit, suggested by Antigones final lines: Welch eine/ Gebhr ich leide von gebhrigen Mnnern/ Die ich gefangen in Gottesfurcht bin what a/ charge I suffer from men to whom charges are due/ I being trapped in reverence for the gods (769). Words such as charge, suffer, trapped belong to the lexis of victimhood, quite unlike the words used in Franklins English translation, which express rousing defiance: See what I suffer, and at whose hands/ Because I respected reverence (ll.907-8). The transition from life to death, as from virgin girlhood to marriage, is marked by material thresholds; for Antigone, the tomb is her bridal chamber (ll.861). Hlderlin stresses this with his imagery of the earth, linking Antigone to the divine powers, such as Zeus, whom Hlderlin calls father of the earth (758) (Hlderlin describes this as his way of making the myths more demonstrable, 786). The emphasis on the physical tomb and on the idea of interment and living

5

Opticon1826, Issue 7, Autumn 2009

burial was one which, Steiner claims, enthralled the early nineteenth-century imagination (1984, 18), with its feel for the Gothic and the unsettling. The periods fascination with graveyards, morgues, memento mori, preserved corpses and death effigies has been discussed extensively (for example: Warner 2006, Bronfen 1992). This might be related to what Foucault (1973) describes as an epistemic shift in attitudes to death during the eighteenth century, when a greater consciousness of self brought forth a fear of the loss of autonomy posed by death. Like love, death posed the transgressive potential for the abandonment of the self, which was both feared and desired. By 1750, as Bronfen (1992) argues, death had become firmly situated in the realm of the other, with excessive ritual marking the transition to heaven, hence refusing finality (86-7). Finality was also denied when attention was shifted to the surviving family, as in Antigone. Thus, contrary to the view suggested by A.W. Schlegel, that Antigone is poorer for its stretching out after the catastrophe of death, it may instead be this prolonged ritual of departing that endears the play to some individuals. The extended laments and the exploration of the consequences that Antigones death has for the surviving family marks death as a ritual of transition. Attention also shifts to the spectator during the course of the play, through the interventions and odes of the chorus. In Antigone, these choral interventions have the function of marking death as a spectacle, helping us to make sense of it through the rituals of crossing-over. Making sense of suffering To understand how the representation of a womans death could have held such sway over the imagination of early nineteenth-century readers or theatre-goers, it is worth considering how representations of suffering and death can arouse pleasure at all. As I argued above, Antigones death is far from being a meaningless act, but is accompanied by attempts to make sense of the act of death, both before and after the act, through the dialogues, conflicts, ethical choices and the entire aesthetic apparatus of the tragedy. In this way, Antigone can be read as an attempt to understand death and realise its position in our lives; such an insight into death may be profoundly pleasurable. Hegel, among with other Hellenists, was particularly impressed with the ancient Greeks ability to cope with the fear of death (Inwood 1992, 71). A further perspective on how Antigones death can be aesthetically powerful can be gained from Nietzsches exuberant work, The Birth of Tragedy (1872), which might be seen as a culmination of the Hellenic spirit of Hegel and Hlderlins day. For Nietzsche, the great value of Greek culture lies in their ability to see and accept the the terror and horror of existence, yet to still managing to exist with a triumphant sense of being (1872, 3; my translation). In exploring the question of how we can make sense of the suffering of death, Nietzsche claims that it is primarily through art that suffering is meaningful: only an aesthetic phenomenon is existence and the world eternally justified (5; my translation). In Antigone, death is justified through being an aesthetic phenomenon, and only as such is it beautiful and meaningful. The Greek ability to find beauty in the greatest horrors of the world is something which, Nietzsche argues, our rational age desperately needs to return to. This is the view articulated poetically by Rilke, when he called beauty the beginning of terror, which we can yet bear, while it gently spurs to destroy us (1996, 201; my translation). It may seem that this attempt to find beauty in even the most wretched conditions of humanity is monstrous, as Michael Tanner suggests (1993, xxiii). In other words, by taking pleasure in representations of events such as a womans sentence to death, it seems that we might be glorifying and seeking the pursuit of such terrible events. But as Daniel Came argues, Nietzsche

6

Opticon1826, Issue 7, Autumn 2009

is not advocating suffering as a goal, but positing it as an inevitable part of life towards which we must adopt some kind of stance, the best being the attempt to see it as beautiful (2006, 56). Not everyone could do this: Goethe claimed that he could not develop a deeply tragic situation without a lively pathological interest; whilst he admired the ancient ability to make terror an aesthetic game, for him the truth of nature seemed too much bound up with the creation of art (in Nietzsche 1872, 22). For some, admiring Antigone as a mere aesthetic phenomenon or philosophical theory is not possible, because of the complex personal and ethical issues it provokes. In valuing the representation of suffering that is Antigone, however, nineteenth-century thinkers have been able to negotiate their own complex attitudes towards horror and death, and have done so through seeing Antigones death as beautiful work of art. Conclusion Antigones endurance over the centuries is testimony to the aesthetic potential contained in its representation of female death. The story has generated a huge variety of interpretations and adaptations as it has taken on new cultural resonances across time, and has tapped into the perpetual, but constantly reinterpreted, concerns about the nature of death, existence and humanity. In investigating the reception of Antigone in early twentieth-century Germany, I have suggested some of the ways in which understandings of Antigone become bound up with broader conceptual and cultural issues: for Hegel, Antigone became part of a dialectic understanding about the self and other; Antigones death articulates our strive towards autonomy and self-realisation. For Hlderlin, it was the pathos of early death, connected with sisterhood and femininity, which made Antigone particularly potent. For both writers, the cultural positioning of women and death in the early-nineteenth century played a role in their attitudes towards the play, suggesting a complex interrelation between fascination with and anxiety about death. Just as death is ritually marked as part of an other realm, so too does Antigone allow us to make sense of death by placing it within an aesthetic framework. At the core of this tragedy is the transformation of a terrible event into a powerful aesthetic phenomenon, and the fascination this arouses signals the attempt to find meaning in finality.

Tara Beaney, 2009 MA Comparative Literature

References Aristotle, Poetics, The Complete Works of Aristotle Vol. II (350BC). Ed. J. Barnes. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984. Benjamin, Walter. Gesammelte Schriften Bd. 2. Aufstze, Essays, Vortrge. Ed. Rolf Tiedemann and Hermann Schweppenhuser. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1977. Bronfen, Elizabeth. Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity and the Aesthetic. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992. Brooks, Peter. Reading for the Plot: Design and Intention in Narrative. Cambridge Mass., London: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Opticon1826, Issue 7, Autumn 2009

Came, Daniel, The Aesthetic Justification of Existence, A Companion to Nietzsche. Ed. Keith Ansell Pearson. Oxford: Blackwell, 2006. De Quincey, Thomas, The Antigone of Sophocles, as represented on the Edinburgh stage (1845), The Collected Writings of Thomas De Quincey Vol. 10. Ed. David Masson. New York: A. & C. Black, 1897. Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception (1973). Trans. A.M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Vintage, 1994. Goldhill, Simon, Antigone and the Politics of Sisterhood, Laughing with Medusa: Classical Myth and Feminist Thought. Ed. Zajko and Leonard. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006, 141162. Hegel, G. W. F. Phenomenology of Spirit (1807). Trans. and ed. A.V. Miller. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977. Hlderlin, Friedrich, Antigon and Anmerkungen zur Antigon (1804), Hlderlin Werke und Briefe Band 2. Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag 1969; 737- 783 and 783-790. Inwood, Michael. A Hegel Dictionary. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992. Irigaray, Luce. Speculum of the Other Woman (1974). Trans. Gillian C. Gill. Ithaca, NY: Cornell, 1985. Lacan, Jacques. Le sminaire, livre vii: Lethique de la psychanalyse. Paris: Seuil, 1986. Nietzsche, Friedrich. Die Geburt der Tragdie (1872). Frankfurt am Main: Insel Taschenbuch, 1987. Rilke, Rainer Maria. Rilke Werke. Kommentierte Ausgabe in vier Bden. Eds. Manfred Engel, Ulrich Flleborn, Horst Nawelski, August Stahl. Leipzig: Insel Verlag, 1996. Schlegel, August Wilhelm, Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature (1768-1803), German Romantic Criticism. Ed. A. Leslie Willson. New York: Continuum, 1982; 175-218. Sophocles, Antigone. Trans. David Franklin, commentary John Harrison. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. Steiner, George. Antigones (1984). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986. Tanner, Michael, Introduction, Nietzsches The Birth of Tragedy. Trans. R.J. Hollingdale, ed. Tanner. London: Penguin, 1993; vii-xxx. Walsh, Keri, Antigone Now in Mosaic: a journal for the interdisciplinary study of literature Sept. 2008 41/3, 1-13. Warner, Marina. Phantasmagoria: Spirit visions, Metaphors and Media into the Twenty-first Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Rainfall Curves - TrinidadDocument26 paginiRainfall Curves - TrinidadStructEngResearcherÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Humanitarian ArchitectureDocument265 paginiHumanitarian ArchitectureRula Rtf100% (2)

- Avalanche Safety Guidebook PDFDocument35 paginiAvalanche Safety Guidebook PDFTivadar HorváthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Huang-The Tragic and The Chinese Subject 2003Document14 paginiHuang-The Tragic and The Chinese Subject 2003cgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Agnons Story References 2015-04-23Document75 paginiAgnons Story References 2015-04-23cgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pagini6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pagini6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Section 15.1-2Document14 paginiSection 15.1-2Brent IshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Greek MeterDocument15 paginiIntroduction To Greek Meterlahor_samÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Editiones Principes in GreekDocument63 paginiList of Editiones Principes in Greekcgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- AssemblyInstructions2 2750Document28 paginiAssemblyInstructions2 2750David OjedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review-Maslen, Remorse, Penal Theory and SentencingDocument7 paginiReview-Maslen, Remorse, Penal Theory and Sentencingcgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Humphreys-The Magic MountainDocument17 paginiHumphreys-The Magic Mountaincgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- A Study in FormDocument17 paginiA Study in Formcgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Ancient Drama ApproachesDocument15 paginiAncient Drama Approachescgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Antologia Textos LinksDocument1 paginăAntologia Textos Linkscgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Neuroscience of Force EscalationDocument1 paginăNeuroscience of Force Escalationcgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Recent Studies on the Structure and Institutions of the Ancient Greek PolisTITLE Figueira Summary of Copenhagen Polis Centre and Other Recent Work on Greek City-StatesDocument16 paginiRecent Studies on the Structure and Institutions of the Ancient Greek PolisTITLE Figueira Summary of Copenhagen Polis Centre and Other Recent Work on Greek City-Statescgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Ince The Very Earliest of TimesDocument10 paginiInce The Very Earliest of Timescgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- 07B3 HubbardDocument1 pagină07B3 Hubbardcgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Abrams at Cornell Online 20jan10Document95 paginiAbrams at Cornell Online 20jan10cgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Quervain-Neural Altruistic PunishmentDocument6 paginiQuervain-Neural Altruistic Punishmentcgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Beaney Fascination AntigoneDocument8 paginiBeaney Fascination Antigonecgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Nimis Fussnoten PDFDocument44 paginiNimis Fussnoten PDFcgarriga1Încă nu există evaluări

- Selectedpoems: Joan Salvat-PapasseitDocument81 paginiSelectedpoems: Joan Salvat-PapasseitOnur BöleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Harman Guilt Free MoralityDocument14 paginiHarman Guilt Free Moralitycgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Nichols FoucaultDocument265 paginiNichols Foucaultcgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Neuroscience of Force EscalationDocument1 paginăNeuroscience of Force Escalationcgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Platonic Emotiveness versus Presocratic-Aristotelian Perception in the Poetry of Luis CernudaDocument12 paginiPlatonic Emotiveness versus Presocratic-Aristotelian Perception in the Poetry of Luis Cernudacgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- A L T D X M M C O: Aus: Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 112 (1996) 279-283Document7 paginiA L T D X M M C O: Aus: Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 112 (1996) 279-283cgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Heirman-Space in Archaic Greek LyricDocument229 paginiHeirman-Space in Archaic Greek Lyriccgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Rhetorical QuestionsDocument94 paginiRhetorical Questionscgarriga2Încă nu există evaluări

- Master and MargaritaDocument17 paginiMaster and MargaritapanuslikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Control of Water: Reporter: Debbie A. Nacilla, Ce5-1Document14 paginiControl of Water: Reporter: Debbie A. Nacilla, Ce5-1Jef de LeonÎncă nu există evaluări

- DramaDocument2 paginiDramaBalz ManzanÎncă nu există evaluări

- NAPNAPAN YOUTH INVESTMENT PLANDocument6 paginiNAPNAPAN YOUTH INVESTMENT PLANJohn Joseph TigeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disaster Preparedness Training For Community OrganizationsDocument75 paginiDisaster Preparedness Training For Community OrganizationsRyan-Jay AbolenciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- University of Phoenix Critical THINKING MGT/350Document4 paginiUniversity of Phoenix Critical THINKING MGT/350jakitatataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Floods On Rice Production in BangladeshDocument5 paginiEffects of Floods On Rice Production in BangladeshPremier PublishersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Incident/Accident Report FormDocument4 paginiIncident/Accident Report Formlordwentworth100% (1)

- Bhopal Gas Tragedy Case StudyDocument10 paginiBhopal Gas Tragedy Case StudyAbhijith MadabhushiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan No. 4Document5 paginiLesson Plan No. 4Pineda RenzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mayon Volcano Historical Eruptions Year/Duration Eruption Character Affected Areas/RemarksDocument4 paginiMayon Volcano Historical Eruptions Year/Duration Eruption Character Affected Areas/RemarksRona Delima SoldeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Narrative ReportDocument14 paginiNarrative ReportQuen Nie100% (4)

- Landslide 2Document16 paginiLandslide 2Prince JoeÎncă nu există evaluări

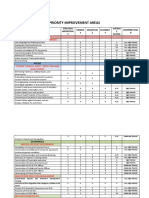

- Priority Improvement AreasDocument2 paginiPriority Improvement AreasJASMIN FAMAÎncă nu există evaluări

- HM (Hotel Management) Magazine Apr 2011 V.15.2Document68 paginiHM (Hotel Management) Magazine Apr 2011 V.15.2rodeimeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kinds of Sentences ExplainedDocument55 paginiKinds of Sentences ExplainedVahdatÎncă nu există evaluări

- DPSouth 24-Parganas81787Document262 paginiDPSouth 24-Parganas81787Kasturi Mandal100% (1)

- Impact of Geographical Phenomena on Caribbean Society and CultureDocument14 paginiImpact of Geographical Phenomena on Caribbean Society and CultureShania W.Încă nu există evaluări

- 5.lahars VenusDocument24 pagini5.lahars VenusFhia Angelika IntongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barangay Resolution Organizing The BDRRMCDocument7 paginiBarangay Resolution Organizing The BDRRMCAnna Lisa Daguinod100% (1)

- Sigmet PDFDocument4 paginiSigmet PDFlim huivoonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eo BDRRMCDocument6 paginiEo BDRRMCAgustin MharieÎncă nu există evaluări

- ACAS II Bulletin 12 - Focus On Pilot TrainingDocument4 paginiACAS II Bulletin 12 - Focus On Pilot TrainingguineasorinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anatomy of An OverrunDocument29 paginiAnatomy of An OverrunUfuk AydinÎncă nu există evaluări

- It Disaster Recovery Planning For Dummies Cheat SH - Navid 323195.HTMLDocument3 paginiIt Disaster Recovery Planning For Dummies Cheat SH - Navid 323195.HTMLChristine VelascoÎncă nu există evaluări

- LECTURE TRANSPORTATION Transcribed by BellosilloDocument7 paginiLECTURE TRANSPORTATION Transcribed by BellosilloCharlie PeinÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Thom Hartmann and The Last Hours of Ancient SunlightDocument8 paginiOn Thom Hartmann and The Last Hours of Ancient SunlightDanut ViciuÎncă nu există evaluări