Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Symbolic Voices (2) : A Complex Reality

Încărcat de

Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Symbolic Voices (2) : A Complex Reality

Încărcat de

Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

RESEARCH INTO PRACTICE

Symbolic voices (2): a complex reality

In 2009, Louise Greenstock gave us an interim report on her qualitative research into the use of graphic symbols in schools. The final findings presented here offer insights into clinical reasoning and ambiguity around professional roles that could also be helpful for other interventions and settings.

hould symbols be used with all children? Are children in the Foundation Stage too young for symbols? And should symbol terminology be more consistent? In Greenstock (2009), I wrote about the progress of my PhD research project into the use of graphic symbols in schools, and how my experience as a teaching assistant had influenced the focus and conduct of my research. Having completed in December 2009, I am now a fulltime researcher in Australia. As well as applying my knowledge on the other side of the world, I wanted to share my final findings with you and consider the implications for practitioners, policy makers and researchers. My research project had the central objective of exploring practitioners experiences of using graphic symbols in Foundation Stage school settings in a geographical region of the East Midlands. I focused on three groups thought to be most likely to use symbols in school settings: teachers, teaching assistants / nursery nurses and speech and language therapists (Abbott & Lucey, 2005). Given the context, I felt it was also important to explore their experiences of working with other practitioners in ways that might be considered inter-professional. The concept of inter-professional working is an important theme in government policy influencing health and education, where practitioners are increasingly expected to foster a culture of collaboration. I considered school settings to be a pertinent example of practitioners working together across different disciplinary and training backgrounds, and was curious about how inter-professional working develops in schools. The ever-increasing use of symbols gave me a very specific and topical context in which to explore the reality. Having received ethical approval from De Montfort University and one of the local NHS Research Ethics Committees, I recruited a sample of 53 participants (9 for the pilot READ THIS IF YOU WANT TO DEVELOP CLARITY AROUND INTERPROFESSIONAL WORKING DECISION MAKING INCLUSIVE COMMUNICATION

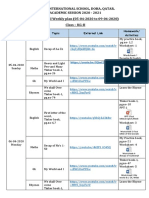

Major themes Theme 1: Practitioners beliefs about which children to use symbols with Theme 2: Practitioners thoughts about childrens understanding of symbols and representation Theme 3: Practitioners accounts of the ways in which symbols are used

First layer subthemes a. Specific children b. All children a. Developmental progression b. Modality a. Developmentally appropriate b. Production and introduction of symbols c. Consistency of symbol use d. Using symbols for specific purposes (see second layer subthemes)

Second layer subthemes

i. Visual timetables ii. Expressing choices and exchange systems iii. Learning to read / literacy skills iv. Rules and expectations of behaviour

Theme 4: Practitioners experiences of implementing symbols in schools

a. The setting b. Roles c. Collaborative working

Figure 1 Major themes and subthemes

study and 44 for the main study) with support from two Primary Care Trusts and four Local Education Authorities. After giving their informed consent, participants took part in a face-to-face interview with me. Interviews took place at schools and health centres. I transcribed the interviews and analysed the data using a form of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The analysis led me to develop a theoretical framework consisting of a series of themes and subthemes, as well as two original theoretical constructs. I presented my preliminary findings in Greenstock (2009). The analysis of data continued after the article was published, and the findings

presented here represent the final version in my PhD thesis. The findings consisted of a thematic framework and a theoretical model which describe the overarching observations of the data. The major themes and subthemes are in figure 1. When they considered using symbols in school settings, each interviewee followed a unique and subjective process of reasoning around questions of how, why, when and with whom. Their decision making processes incorporated each of the four major themes: which children to use symbols with, the childs needs and developmental capabilities, how symbols could be used and how the strategy

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE AUTUMN 2011

23

RESEARCH INTO PRACTICE

could be implemented. I developed a model of reasoning to reflect this (figure 2). The practitioner may consider any or all four of the components identified in any order, with any starting point. The model can be applied to individual practitioners accounts of thinking about how to use symbols. For example, figure 3 shows how a speech and language therapist considered a client who has physical difficulties and expressive communication needs and decided to introduce a choice board to facilitate the child in expressing choices at singing time on the carpet. Figures 4 and 5 also come from the original dataset, and show how the model can be applied to an individual teacher and a teaching assistant. The interview data reflected practitioners beliefs and ideas about each of the four major themes. There were areas of consistency and agreement, as well as discrepancies and tensions in their accounts. Theme 1: Practitioners beliefs about which children to use symbols with This theme directly addresses the question about whether symbols should be used with all children or specific children. In general, the practitioners were divided in their opinions. This reflected a tension in the data, and both sides of this debate were represented by practitioners in each of the three professional groups. Many expressed the belief that symbols should only be used with children with a specific need for them, and these needs were often related to their difficulties in certain areas of learning and communication. In contrast, a number argued that they could potentially benefit the full range of children but the reasons given varied among the professional groups. Educational practitioners tended to suggest this approach because they felt symbols could support all children in the setting. In contrast, speech and language therapists often suggested using symbols with all children as a way of ensuring communication opportunities and partners are made available to individual children using symbols to participate. The disparity between professional groups reflected some overarching differences in professional roles and disciplinary background. Theme 2: Practitioners thoughts about childrens understanding of symbols and representation Practitioners accounts of using symbols were frequently related to their perceptions of childrens understanding of representation and their ability to understand the referential nature of symbols. This aspect of cognitive understanding was seen as a developmental process. Many practitioners referred to childrens development in understanding representation, and gave accounts of assessing their development in this area and differentiating their use of symbols accordingly. Many practitioners suggested that childrens symbolic development occurred in stages, which could be related

Figure 2 When to use symbols Who which children Figure 3 Singing time on carpet Schoolbased speech and language therapist Why childrens needs Choice boards express choice through pointing Expressive communication needs Child with physical difficulties

Practitioner

How to use symbols

to the appropriate use of symbols and other representational items. Childrens understanding of symbols was often related to the modality of various forms of representation. Practitioners referred to objects of reference, photographs and symbols as possible modes used to represent ideas and information to children. Many times in the data practitioners referred to the use of multi-modal or multi-channel approaches. Using more than one mode (for example, text and symbols), and/or more than one channel (for example, auditory and visual), was believed to increase the accessibility of the message to a range of children. These findings did not appear to suggest that practitioners felt children were too young for the use of symbols, but did indicate that age and developmental stage were a consideration when using various modes of representation. Theme 3: Practitioners accounts of the ways in which symbols are used The practitioners interviewed appeared to have some firm ideas about how symbols should be used, incorporating developmental differentiation, how to produce and introduce symbols, the consistency of symbol use, and specific purposes to use symbols for. Relating to their beliefs about childrens developmental understanding of symbols, many gave accounts of the ways in which they would differentiate activities so they were developmentally appropriate. These practitioners frequently referred to the need to assess childrens level of symbolic development before making decisions about which mode of representation to use. Most were in agreement that objects of reference would be most suitable for use with children at an earlier stage of development. Photographs were considered the next stage in this hierarchy, and symbols and text to be more advanced. The hierarchy of understanding these modes of representation was referred to by practitioners in each of the three professional groups, and there was agreement across the data about the need to differentiate for different developmental abilities. Many practitioners expressed clear views about the need to produce and introduce symbols in certain ways to children in this age group. The production of symbols was usually

supported by software, and practitioners were in agreement that they should be introduced to children in small numbers so as not to overwhelm. There was some level of agreement about the need to use symbols consistently. Practitioners appeared to believe that symbols used throughout the school environment should be visually similar to support children at times of transition by providing something familiar in other environments. This finding was believed to be related to the level of anxiety experienced by children in the Foundation Stage age group. In contrast, some practitioners argued that individualised strategies were more important when symbols were being used to enable individual children to communicate and participate. Practitioners gave accounts of using symbols for a number of specific purposes. The most frequent were visual timetables, choices and exchange systems, developing literacy skills and representing rules and expectations of behaviour. The most dominant way of using symbols across all three professional groups was as part of symbol-supported visual timetables. Visual timetables were used to represent sections of time, and activities within the session and symbols were displayed in a vertical or horizontal line. Practitioners gave accounts of going through the visual timetable each day with the children and removing symbols to show time passing. This was seen as a tool to support children who experience anxiety about separating from caregivers or have difficulties in attention and staying on-task. Symbol-supported choice boards, the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS), literacy and representing rules were all mentioned as additional ways of using symbols. Using symbols to support literacy in particular for word recognition - was unique to the educational practitioners. However, using symbols to represent rules and expectations was referred to by practitioners across all three professional groups. Theme 4: Practitioners experiences of implementing symbols in schools This theme was the most relevant to practitioners experiences of working interprofessionally in schools. Most of those

24

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE AUTUMN 2011

RESEARCH INTO PRACTICE

Figure 4 Accessible throughout the session All children Figure 5 Accessible when choosing activities Teaching assistant Child with English as an additional language

Teacher

Visual timetable

Separation anxiety

Symbolised activities in book

Struggles to comprehend instructions

interviewed gave accounts of their experiences of the actual implementation of symbols in schools. The implementation process appeared to be influenced by contextual factors relating to ways of working in the school setting. Some practitioners highlighted that speech and language therapists were visitors in the school and this appeared to affect the amount of influence they felt they had. A number of speech and language therapists expressed frustration with the way symbols were implemented in schools, mainly related to symbols not being used enough. The practitioners accounts of their use of symbols in schools appeared to suggest that in some settings there were specific roles associated with each professional group. Speech and language therapists were frequently seen as experts and expected to deliver training and support in the ongoing implementation of symbols. Early years practitioners were frequently seen as responsible for carrying out the strategy or programme suggested by the speech and language therapist and maintaining resources. The role of the teacher was the most ambiguous in the data and it was not clear if teachers had any consistent role in this area of practice. These findings reflected a number of tensions in the data relating to discrepancies in interpretations of the roles of various practitioners. In some cases there appeared to be resistance and conflict between practitioners and their colleagues. The most dominant factors influencing collaborative working were time and availability, communication and perceptions of professional roles. Many practitioners commented on the lack of time available to discuss the use of symbols with colleagues and many highlighted the difficulty of releasing educational practitioners from duties to talk face-to-face. Communication and interpersonal skills were frequently mentioned as a factor in the success of collaborative working, and speech and language therapists in particular referred to the need for diplomacy. My findings led to the development of a suggested series of practical strategies for improving childrens experiences of using symbols, many of which applied to all of the professional groups:

When using symbols, consider which children the intervention is targeted at. Consider whether it is just a specific child, or group, or more designed to support all children. Always consider the developmental ability of the child in terms of their understanding of representation. Speech and language therapists are skilled in identifying this. Differentiate the use of symbols or other modes of representation to the childs level of understanding (for example, objects of reference, photos or symbols). Introduce symbols in small quantities and explain or teach their meaning. Discuss as a team whether to use one symbol set consistently or differentiate use depending on the child or the purpose. Consider the objectives and professional role of all colleagues involved in the implementation of symbol use. Define roles where necessary and make use of any opportunity to communicate and share ideas and reasoning.

of representation and this gave some interviews a rather abstract dimension. This is of great interest in considering the cognitive processes in everyday practice, an aspect which could be explored further in the future. Regardless of attitudes towards the use of symbols and beliefs about their appropriate usage, the implementation of symbol use in schools is a complex reality. Practitioners in each of the three professional groups considered a range of factors - and their reasons for using symbols with one child may be very different to using them with another. Practitioners in all three professional groups called for more training and more time to discuss and plan the symbol strategies collaboratively. The practitioners who expressed the most satisfaction with their experiences of using symbols referred to respectful, supportive and mutually advantageous experiences of working with other professionals. This suggests that there is value in the move towards increasing inter-professional practice. It also confirms that examples of good practice can be recorded and shared as a result of conducting research which places the practitioners voice SLTP at its heart. Dr Louise Greenstock, formerly at De Montfort University, is now a Research Fellow at the Australian Health Workforce Institute, University of Melbourne, email lgreens@unimelb.edu.au. References Abbott, C. & Lucey, H. (2005) Symbol communication in special schools in England: the current position and some key issues, British Journal of Special Education 32(4), pp.196-201. Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology, Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), pp.77-101. Greenstock, L. (2009) Symbolic voices, Speech & Language Therapy in Practice Summer, pp.12-14.

Think deeply

Practitioners think deeply about the ways in which they use symbols and base their reasoning on the needs of the children they work with. Using symbols does seem to frequently involve working with one or more other practitioners who may or may not have contrasting disciplinary and training backgrounds. While practitioners may be expected to work inter-professionally, it must be recognised that every practitioner is a unique individual with their own reasoning and decision making processes. There may be trends in professional reasoning across and within professional groups, but there may also be personal differences which are hard to make explicit in day to day practice. There were discrepancies and inconsistencies in the terminology used to describe and discuss symbols, but there was no indication that this caused any major problems in daily practice. This issue was part of a more philosophical conversation with some participants about the meaning

REFLECTIONS DO I TAKE AN EVIDENCE BASED APPROACH TO COLLABORATIVE WORKING? DO I UNDERSTAND MY OWN REASONING PROCESSES AND SEEK TO UNDERSTAND THOSE OF OTHERS? DO I GIVE SUFFICIENT PRIORITY TO DEVELOPING SKILLS AROUND NETWORKING AND DIPLOMACY?

What ideas has this article given you? Let us know! See Speech & Language Therapy in Practices Critical Friends information at www.speechmag.com/About/Friends.

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE AUTUMN 2011

25

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Winning Ways (Winter 2007)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Winter 2007)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Here's One I Made Earlier (Spring 2008)Document1 paginăHere's One I Made Earlier (Spring 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Mount Wilga High Level Language Test (Revised) (2006)Document78 paginiMount Wilga High Level Language Test (Revised) (2006)Speech & Language Therapy in Practice75% (8)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Turning On The SpotlightDocument6 paginiTurning On The SpotlightSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Winning Ways (Spring 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Spring 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- In Brief and Critical Friends (Summer 09)Document1 paginăIn Brief and Critical Friends (Summer 09)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Winning Ways (Autumn 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Autumn 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- In Brief (Winter 10) Stammering and Communication Therapy InternationalDocument2 paginiIn Brief (Winter 10) Stammering and Communication Therapy InternationalSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Winning Ways (Summer 2008)Document1 paginăWinning Ways (Summer 2008)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Here's One Sum 09 Storyteller, Friendship, That's HowDocument1 paginăHere's One Sum 09 Storyteller, Friendship, That's HowSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- In Brief (Autumn 09) NQTs and Assessment ClinicsDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Autumn 09) NQTs and Assessment ClinicsSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Here's One Spring 10 Dating ThemeDocument1 paginăHere's One Spring 10 Dating ThemeSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Ylvisaker HandoutDocument20 paginiYlvisaker HandoutSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Here's One Summer 10Document1 paginăHere's One Summer 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- In Brief (Summer 10) TeenagersDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Summer 10) TeenagersSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Winter 10Document1 paginăHere's One Winter 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- In Brief and Here's One Autumn 10Document2 paginiIn Brief and Here's One Autumn 10Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Spring 11) Dementia and PhonologyDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Spring 11) Dementia and PhonologySpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applying Choices and PossibilitiesDocument3 paginiApplying Choices and PossibilitiesSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Spring 11Document1 paginăHere's One Spring 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- My Top Resources (Winter 11) Clinical PlacementsDocument1 paginăMy Top Resources (Winter 11) Clinical PlacementsSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief... : Supporting Communication With Signed SpeechDocument1 paginăIn Brief... : Supporting Communication With Signed SpeechSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Practical FocusDocument2 paginiA Practical FocusSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief (Summer 11) AphasiaDocument1 paginăIn Brief (Summer 11) AphasiaSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Here's One I Made Earlier Summer 11Document1 paginăHere's One I Made Earlier Summer 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Pathways: Lynsey PatersonDocument3 paginiNew Pathways: Lynsey PatersonSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding RhysDocument3 paginiUnderstanding RhysSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Here's One Winter 11Document1 paginăHere's One Winter 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Brief Winter 11Document2 paginiIn Brief Winter 11Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Here's One I Made EarlierDocument1 paginăHere's One I Made EarlierSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liver Disease Management & TransplantDocument4 paginiLiver Disease Management & TransplantMusike TeckneÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of ExaminerDocument2 paginiList of ExaminerndembiekehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Claims of Fact, Policy and ValueDocument7 paginiClaims of Fact, Policy and ValueGreggy LatrasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Application Form SaumuDocument4 paginiApplication Form SaumuSaumu AbdiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction Two Kinds of ProportionDocument54 paginiIntroduction Two Kinds of ProportionMohit SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Croft Thesis Prospectus GuideDocument3 paginiCroft Thesis Prospectus GuideMiguel CentellasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Loyola International School, Doha, Qatar. Academic Session 2020 - 2021 Home-School Weekly Plan (05-04-2020 To 09-04-2020) Class - KG-IIDocument3 paginiLoyola International School, Doha, Qatar. Academic Session 2020 - 2021 Home-School Weekly Plan (05-04-2020 To 09-04-2020) Class - KG-IIAvik KunduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Checklist of Documents 2019 Cambridge AccreditationDocument4 paginiChecklist of Documents 2019 Cambridge AccreditationLiz PlattÎncă nu există evaluări

- IGCSE Science (Double Award) TSM Issue 2Document52 paginiIGCSE Science (Double Award) TSM Issue 2frogfloydÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ass AsDocument1 paginăAss AsMukesh BishtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personal Teaching PhilosophyDocument4 paginiPersonal Teaching Philosophyapi-445489365Încă nu există evaluări

- UTS Character StrengthsDocument3 paginiUTS Character StrengthsangelaaaxÎncă nu există evaluări

- EF3e Elem Filetest 12a Answer SheetDocument1 paginăEF3e Elem Filetest 12a Answer SheetLígia LimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dli v17Document69 paginiDli v17Gavril Mikhailovich PryedveshtinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan: Characteristics of LifeDocument4 paginiLesson Plan: Characteristics of Lifeapi-342089282Încă nu există evaluări

- Transactional and Transformational LeadershipDocument4 paginiTransactional and Transformational LeadershipAnonymous ZLSyoWhQ7100% (1)

- SolutionsDocument19 paginiSolutionsSk KusÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Psychology of Human Strengths Fundamental Questions and Future Directions For A Positive PsychologyDocument325 paginiA Psychology of Human Strengths Fundamental Questions and Future Directions For A Positive PsychologyAndreea Pîntia100% (14)

- PBL Rhetorical AnalysisDocument6 paginiPBL Rhetorical Analysisapi-283773804Încă nu există evaluări

- Esm2e Chapter 14 171939Document47 paginiEsm2e Chapter 14 171939Jean HoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Outside Speaker EvaluationDocument2 paginiOutside Speaker EvaluationAlaa QaissiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Updated SaroDocument559 paginiUpdated SaroBiZayangAmaZonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Micro Teaching and Its NeedDocument15 paginiMicro Teaching and Its NeedEvelyn100% (2)

- Department of Education: Class ProgramDocument2 paginiDepartment of Education: Class ProgramGalelie Calla DacaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Republic of The Gambia: Ministry of Basic and Secondary Education (Mobse)Document43 paginiRepublic of The Gambia: Ministry of Basic and Secondary Education (Mobse)Mj pinedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DBA BrochureDocument12 paginiDBA BrochureTacef Revival-ArmyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Individual Performance Commitment and Review Form: Basic Education Service Teaching Learning Process (30%)Document3 paginiIndividual Performance Commitment and Review Form: Basic Education Service Teaching Learning Process (30%)Donita-jane Bangilan CanceranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planting Our Own SeedsDocument6 paginiPlanting Our Own Seedsapi-612470147Încă nu există evaluări

- Educational Scenario of Kupwara by Naseem NazirDocument8 paginiEducational Scenario of Kupwara by Naseem NazirLonenaseem NazirÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is The Common CoreDocument10 paginiWhat Is The Common Coreobx4everÎncă nu există evaluări