Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Perceptions On Captive Malayan Porcupine (Hystrix Brachyura) Meat by Malaysian Urban Consumers

Încărcat de

kebajikan7972Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Perceptions On Captive Malayan Porcupine (Hystrix Brachyura) Meat by Malaysian Urban Consumers

Încărcat de

kebajikan7972Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Health and the Environment Journal, 2012, Vol. 3, No.

Perceptions on Captive Malayan Porcupine (Hystrix brachyura) Meat by Malaysian Urban Consumers.

Norsuhana AHa*, Shukor MN b, Aminah A c

Biology Section, School of Distance Education, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), 11800 Minden,Penang Malaysia b School of Environmental Science and Natural Resources, Faculty of Science and Technology, University Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), 43600 Bangi, Selangor Malaysia c School of Chemistry Science and Food Technology, Faculty of Science and Technology, University Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), 43600 Bangi, Selangor Malaysia d Department of Wildlife and National Parks (DWN,), km 10, Jalan Cheras 56100 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia Corresponding author email: norsuhana@usm.my Published 31 January 2012

a

______________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT: The objective of this study is to investigate the acceptance and purchasing behaviours of Malaysian consumers for captive bred Malayan porcupine (Hystrix brachyura) meat as an alternative meat product in the domestic market. Result showed that 53.5% of the respondents acknowledged that porcupine meat can be eaten and is according to Muslim law (Halal). However, only 20% of the respondents had tried the meat. More than half (55.8%) of the respondents indicated that porcupine meat is delicious while 11.6% stated differently. Respondents preferred to try porcupine meat if it possesses high nutritional values, is of reasonable price and is good for health (62.4%). From the evaluation, 53.8% of the respondents are willing to pay if the price is higher than beefs price. Suggested price is between RM20.00 to RM25.00 / kg. Our data also indicated meat preference for wild porcupine meat is slightly greater than captive with percentages of respectively 54.7% and 45.3%. The reason of the choice is quality. Marketing strategy was suggested to promote porcupine meat in restaurants with ready cooked food. Packaging method was also introduced with pre-cooked food in packed form. Keywords: Consumer acceptance; Malayan porcupine meat; Malaysian; market strategy

Introduction It is very difficult to evaluate Malaysian consumers perceptions in their food preferences especially food from game meat. This is because no reliable data had indicated the answers. Malaysian consumers get their source of meat from domestic animals such as chicken, beef and lamb. These animals are mostly farmed in order to meet the market and wholesalers demand. Meats from the domestic animals are known

to have high fat and cholesterol content. Thus, consumers prefer an alternative meat such as game meat in their diet to get the nutrients they require. Nowadays, consumers were changing their food preference because of the increasing awareness in their food issues and health concerns (Hoffman, 2005). Consumers in developing countries also took the same action by reducing their meat intake due to health concerns (Beckers et al., 1998; Becker et al., 2000; Richardson et al., 1993; Richardson et al., 1994). 67

Health and the Environment Journal, 2012, Vol. 3, No. 1

In Malaysia, a previous study indicated that the frequency of daily meat consumption by consumers is more than twice per week in urban area (Norsuhana, 2008). The main reason stated by consumers is because of the nutrient contents that can fulfill their daily diet. Meat diet can provide important nutrients that are needed by the human body. Red meat, especially, contains high biological values of protein and important micronutrients, which are essential for a good health (Willianson et al., 2005) can also cause exceeding intake of fat if taken regularly (Given et al., 2006). For example, saturated fatty acid (SFA) is positively correlated to disease such as coronary heart disease. Balance intake of Omega 3 and Omega 6 is also important in the diet. The ideal ratio of Omega 3 to Omega 6 shall be less than four, otherwise it may cause heart problem (Enser, 2001). Throughout the years, Malaysian consumers have been improving their standard of living and knowledge about healthy balanced diet. This is perhaps due to alleged relationship of fat intake and its contribution to the problems such as heart disease. Consumers expect that meat products in the market would have high nutritional values, fresh, lean and contain adequate juiciness, flavour and tenderness (Hofman and Wiklund, 2006). It should be the same as other game meat that has already been established in the market. According to Hofman (2001), the tenderness of game meat is similar to beef. Hoffman (2000) also reported that game meat contains lower fat level compared to beef, pork or mutton and has an average fat content of 2-3% only. Similar report was produced by Dahlan and Noor Farizan (2000) where venison meat is lower in fat level and has high level of Omega 3 and Omega 6. Based on the report, Malaysian consumers shall change their preferences with meats come from natural methods or organic sources. According to Hoffman and

Bigalke (1999), game meat is also known as organic product as it comes from natural production or original habitats. Thus, the demand of game meat for market and wholesalers has increased similar to other organic products. For the same reason, ostrich farming has also been growing because of its positive value in nutrients content which concerns the health. For commercialization of new products, consumers behaviour is the most important characteristic that should be considered first. Radder and Roux (2005) found two factors which influenced consumers preference to game meat namely the consumer-related forces and market-related forces. The former includes health consideration, sensory variables, social interactions, familiarity and habit, psychographics and demographics while the latter involves prices, distributions and promotions. Malayan porcupine (Hystrix brachyura) is also one of the new wildlife species proposed to be commercialized as a meat product due to its high reproductive performances, large body size and easy management (Zainal, 1998). Previous study also indicated that Malayan porcupine meat is a healthy meat due to its lower fat content (3.6 %) and has an ideal ratio of PUFA to SFA (0.7) (Norsuhana, 2007). As the biggest animal classified under Order Rodentia in South East Asia, this species is protected under Wildlife Act (1972) by Malaysian Law. Under this law the hunting of this species is done only after approval license is obtained from The Department of Wildlife and National Parks (DWN) of Malaysia and hunting is limited to five porcupines per year. This new wildlife species can provide an economic income for farmers if clear information and responds from consumers are obtained. However, until today, no reliable data have been reported on consumers perceptions and purchasing 68

Health and the Environment Journal, 2012, Vol. 3, No. 1

behaviours on porcupine meat in Malaysia. Therefore, the objectives of the research were to (i) study and evaluate the perceptions, and (ii) to identify the purchasing pattern of urban consumers in Klang Valley, Malaysia. The finding is important so that the Malayan porcupine (Hystrix brachyura) can be the alternative source of healthy game meat to meet the target of the markets in near future. Methods The survey was conducted using a selfadministered structure of questionnaires. The pattern of questions was developed under demographics and socioeconomics. As to evaluate the consumers perceptions and to identify their purchasing patterns, the study was conducted on 170 respondents living in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Klang Valley was selected because it is one of the biggest cities in Malaysia and has a population of consumers with different demographic and socioeconomic life. TABLE 1 summarizes the patterns of demographics and socioeconomics of the respondents which

was used as the main sample in the questionnaires. Since the study aimed to commercialize Malayan porcupine as new game meat, the questionnaires were divided in two sub topic which included the perception to alternative meat (another meat such as venison, rabbit, ostrich, and camel not include chicken, beef, lamb and pork) and perceptions to Malayan porcupine meat. These types of questions are in line with main references point as to ensure respondents give direct responses to the question's aims. Preliminary test was conducted on the questionnaires. 20 respondents were selected to answer all the questions. From the feedback obtained from the respondents, the questionnaires were modified again according to requirement prior to the survey. The data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, 2002), version 11.5 for Windows. Chai square test (2) was performed at 95% of confidence level (p<0.05).

69

Health and the Environment Journal, 2012, Vol. 3, No. 1

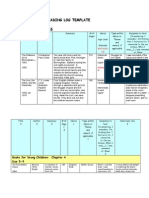

TABLE 1- Percentages distribution of sample characteristics (demographic and Socioeconomic)

Items Demographic Age 20-30 31-40 41-50 Genders Male Female Nations Malay Chinese Indian Educations Primary school Secondary school Certificate/Diploma Degree Master/PhD Socioeconomic Employments Government Private Self-employed Housewife Student Others Total monthly income/salary None <RM500 RM500-1000 RM1001-1500 RM1501-2000 RM2001-2500 >RM2501 No. respondents Percentages

77 44 49

45.3 25.9 28.8

72 98

42.4 57.6

117 41 12

68.8 24.1 7.1

4 51 31 54 30

2.4 30.0 18.2 31.8 17.6

102 42 8 2 9 7

60.0 24.7 4.7 1.2 5.3 4.1

6 35 39 25 24 41

3.5 0.0 20.6 22.9 14.7 14.1 24.1

70

Health and the Environment Journal, 2012, Vol. 3, No. 1

Results Perception on alternative meat (other meat excluded of chicken, beef, lamb and pork) The results show that 55.6% of respondents had tried the alternative meat (excluded of chicken, beef, lamb and pork) whereas 43.5% of respondents stated that they had not tried (p<0.05). TABLE 2 shows the percentages of alternative meat that had been tried by respondents with lead by venison (71.9%) and followed by rabbit (58.3%), ostrich (38.5%), other game meat (37.5%) and camel (26.0%). Barking deer and mouse deer were considered the least intake by

consumers with percentages of 24.0% and 18.8%, respectively. Respondents were asked to state how they perceive the availability of this meat from their residence area. Majority of respondents (61.5%) indicated that they acquired meat from restaurants (cooked), whereas 33.3% from hunters, 30.2% purchased them from fresh market and 18.8% purchased them directly from farm (p<0.05). Our data also indicate that the reason for them to turn to alternative meat was to the change in their appetite (83.3%) compared to high nutrients value (28.1%) and available from hunters (24.0%). Only 9.4% of respondents selected game meat product as complement for better health.

TABLE 2 Percentage for alternative meats that have been eaten by respondents. The percentage are statistically difference among type of meats (p<0.05) Type of meats Camel Rabbit Ostrich Venison Barking deer Mouse deer Others Perception on porcupine meat Our data indicate that 23.5% of the respondents believe that porcupine meat is Halal to be eaten by Muslims, while 53.5% believed that it is not (p<0.05). Only 22.9% were not sure. In order to evaluate the consumers knowledge about the porcupine meat, they have to state their perceptions on whether this meat can give benefits to our health or not. To this point, most respondents (76.5%) agreed that Malayan porcupine meat has potential for health benefit in contrast with another 23.5% who believed otherwise (p<0.05). Furthermore, when the respondents were asked whether they have consumed the porcupine meat before, 20% of the respondents did have the experience of consuming porcupine meat, with more than half of the respondents stated that this meat was delicious (55.8%), while only 11.6% stated otherwise. Assessment of the future market of porcupine meat indicated that more than half of respondents (62.4%) preferred to try porcupine meat if it possesses high nutritional values, comes with reasonable price and is good for health (p<0.05). 53.8% 71 Frequency of percentage (%) 26.0 58.3 38.5 71.9 18.8 24.0 37.5

Health and the Environment Journal, 2012, Vol. 3, No. 1

of respondents would still purchase the meat even if the price is higher than beef. The reason why the respondents were in favour of porcupine meat is probably due to its physical appearance (59.4%) and because they were not familiar to the taste of the meat (46.9%). Our data further revealed that majority respondents (87.7%) preferred to buy porcupine meat (p<0.05) if the price is between RM20.00 and RM25.00/kg, followed by RM26.00 to RM30.00/kg (9.4%), RM36.00 to RM40.00/kg (0.9%) and RM41.00 to RM45.00/kg (1.9%). Respondents have no specific preference on either captive or wild meat porcupine. 54.7% of the respondents preferred to buy wild meat, while the rest preferred captive porcupine meat. Respondents believed that the wild porcupine meat has high nutrient content (44.8%). Only 25.0% of the respondents chose captive porcupine meat due to its higher nutrient content than wild meat, with 27.1% believed that captive breed is free from disease and 4.2% for personal or other reasons. In market evaluation study, TABLE 3 indicates the total results where no significant difference was found (p>0.05) in respondents ages. Respondents ages between 20-30 years old were willing to buy Malayan

porcupine meat if the price is higher than beef (24.5%) and followed by respondents ages between 31-40 years old (15.1%) and respondents ages between 41-50 years old at the least (14.1%). For ethnicity comparison, Malay consumers showed the highest percentage (p<0.05). Malay, Chinese and Indian participants who were willing to pay for the porcupine meat if the price is higher than beef are 37.7%, 13.2% and 0.9%, respectively. Whereas degree and diploma holder (19.8% and 15.1%) and respondents who were working in the government sector (31.1%) showed the highest percentage (p<0.05) to purchase porcupine meat if the price is higher than beef. 34% respondents from the government sectors who were not willing to purchase porcupine meat if the price is higher than beef. This evaluation shows that only less than half of the consumers from the government sector and consumers ages between 31-50 years old would not choose porcupine meat if the price is higher the price of beef.

72

Health and the Environment Journal, 2012, Vol. 3, No. 1

TABLE 3-Number and percentage respondents who are preferred and not preferred to Buy porcupine meat if the price are higher than beefs price based on the background of respondents (n=106 respondents).

Criteria Ages 20-30 31-40 41-50 Gender Male Female Race Malay Chinese Indian Education Level Primary School Secondary School Certificate/Diploma Degree Master/PhD Job Government employees Private employees Self-employee Student Other Monthly income None RM500-1000 RM 1001-1500 RM 1501-2000 RM 2001-2500 >RM2501 Willing to buy No. respondent 26 16 15 29 28 40 14 3 2 10 16 21 8 % 24.5 15.1 14.1 27.5 26.4 37.7 13.2 2.8 1.9 9.4 15.1 19.8 7.5 Not willing to buy No. respondent 18 14 17 21 28 42 6 1 1 19 9 14 6 % 17.0 13.2 16.0 19.8 26.4 39.6 5.7 0.9 33.3 17.9 8.5 13.2 5.7

33 16 3 2 3 2 9 13 7 9 17

31.1 15.1 2.8 1.9 2.8 1.9 8.5 12.6 6.6 8.5 16.0

36 9 1 2 1 1 11 13 9 9 6

34.0 8.5 0.9 1.9 0.9 0.9 10.4 12.3 8.5 8.5 5.7

73

Health and the Environment Journal, 2012, Vol. 3, No. 1

TABLE 4- Reason stated by respondents for buying captive porcupine or wild porcupine.

Percentage Captive porcupine Wild porcupine (n=48 respondents) (n=58 respondents) 25.0 44.8 43.8 58.3 27.1 4.2 8.3

Reasons Nutrient content Meat quality Free from disease Personal reason/Others

Discussions More than half (55.6%) of the respondents took alternative meat in urban area of Peninsular Malaysia. Different result was reported in Africa with 69% respondents took alternative meat (Radder and Roux, 2005). Factors such as development and growth of wildlife farming in Africa have varied the consumer's choice (Hoffman and Wiklund, 2005). Respondents in Malaysia strongly preferred alternative meat such as rabbit and venison with several farms being established to breed rabbit and venison for their meat (Nor, 2003; Anon, 2006). Perak state has produced 8.7 ton of venison meat in 2002 and the amount has slightly increased annually to 11.8 ton in 2005(Anon, 2007). Data collected from Department of Veterinary Service, Malaysia also showed increase in the total number of venison and rabbit with 8077 venison and 7181 rabbits in 2003 to 8402 venison and 7598 rabbits in 2004. The popular meat regularly taken by the respondents are meat from animal species that has already been commercialized in the market that include deer, rabbit and ostrich. Increase in the demand for the meat of wildlife species shows the opportunity for porcupine meat as the alternative source of meat. Demand for other commercial wild stocks such as camel, barking deer and mouse deer were lower than 30%. The difficulty in getting these types of meat in

the market may be the reason of low demand. The results showed that more than half of the respondents (61.5%) got their meat from restaurants suggesting that the marketing strategy for Malayan porcupine meat should be developed in restaurants with ready cooked food. Zotte (2002) reported that due to the factor of having limited time, consumer's demand towards meat nowadays has changed to cooked meat. Gale et al. (2000) studied the marketing of veal in Canada and suggested that the restaurant was a good medium to market and promote the meat. Hoffman et al., (2003) also proposed restaurant as a medium to promote game meat to tourists. In our questionnaires, no questions have directly asked respondents to suggest any marketing strategy for Malayan porcupine meat. However, from the result, only 29% of the respondents who purchased alternative meat from fresh market claimed that marketing through fresh market probably less effective than marketing through restaurant. 76.5% of the respondents stated that they knew porcupine meat is a healthy meat. This statement is scientifically unreliable because to date, no study has been conducted nor reports about the nutrients composition in porcupine meat. However, information in other game meat may affect the statement, because more than half of the respondents (67.6%) are among professional levels. 74

Health and the Environment Journal, 2012, Vol. 3, No. 1

Respondents assumed that wildlife meat contains higher nutritive value than domestic livestock. This mindset might also give advantages to porcupine meat as it is a wildlife animal. Lack of preference on porcupine meat might be associated with the difference in culture and social life. Study in United State showed that social structure influenced meat intake for Asian and Coloured people. Meat intake by Asian and Coloured people is higher than Western people; even though Asians food may not totally based on meat compared to western food (Gossard and York, 2003). Therefore, it is possible that in the future, factors such as a change in the way of lifestyle (culture) and social life can help consumers to accept porcupine meat. Price is a pressuring factor especially in marketing. It is the core factor described in food preference by users (Radder and Roux, 1995). In developed country, price becomes the core factor and key indicator for user's assessment. Therefore, manufacturers must compete in the aspect of price, quality and diversity of the meat products (Harrington, 1994). The percentage of respondents willing to purchase porcupine meat even if the price is higher than beef is higher compared to respondents in an African study with only 22% of the respondents agreed to purchase wild animal meat if the price is higher than prices of other meat (Hoffman et al., 2005). Respondents aged between 20-30 years old preferred buying porcupine meat if the price is higher than beef (24.5%). From the results, younger respondents were willing to spend more money to get better health. Harrington (1994) reported that youth and young group were more sensitive towards meat intake. Different reaction were shown by respondents in Australia where

respondents ages between 50-60 years old had the same opinion as youth ages between 20-30 years on health issues (Russell and Cox, 2004). Youth reduces red meat intake and consumes more white meat as the latter gives bad effect to the health (Santos and Booth, 1996). The consumption per capita of red meat declined in worldwide (Grunert, 2006) probably caused by consumer's negative perception on red meat and associated it with cardiovascular and other diseases. Respondents aged between 31-40 and 41-50 years old also preferred buying porcupine meat if the price is higher than beef (15.1%). The price between RM20.00 and RM25.00/kg was proposed by majority respondents who were willing to buy porcupine meat. Similar results were found by Gale et al. (2000) for consumers who interested and are willing to purchase veal meat. Wilkie et al. (2005) reported that if the prices of wild meat, fish, chicken and domestic animal were slightly higher, it would decrease the demand from consumers. Therefore, porcupine meat marketed at lower prices to ensure its purchasing ability by consumers from multiple economic backgrounds. It should also be noted the costs might be neglected by the consumers if the meat is of high nutritional value. Research by Dransfield (1998) revealed that consumers were willing to pay more if the meat contains high nutritional value. Quality is an important factor to influence the decisions in purchasing either captive or wild porcupine meat. If the quality of the captive porcupine meat is similar or better than wild porcupine meat, respondents may not hesitate to choose captive porcupine meat. Different scenario was shown by African consumers, where quality was not emphasized by users when they buy wild 75

Health and the Environment Journal, 2012, Vol. 3, No. 1

animal meat compared to domestic meat (Hoffman et al., 2004). Meat quality in market comprises intrinsic indicator (label, place of purchase, price and country of origin), extrinsic indicator (color, marbling, and leanness) and food quality (sense, tenderness, color, smell, leanness, juicy and free from grees) (Becker et al., 1998). Nowadays, quality of meat is more complex and influenced by many factors such as management system, breed, genetic, nutrition, handling steps before slaughtering, slaughtering process and storage system (Andersen et al., 2005). The quality of wild animal meat can be indicated by its colour. Wild meat usually is dark in colour and appears unattractive. Two factors known to affect the quality of the meat are stress during the slaughtering process and the nature of the wild animal which is more active than the domestic animal (Hoffman et al., 2005). Conclusion Only one fifth of respondents have tried porcupine meat. However, more than half (62.4%) strongly agreed to try the meat if it is of high nutritional values, sold at reasonable price and is good for health. We conclude that efforts in commercializing porcupine meat should include promotions to expose widely the advantages and disadvantages of Malayan porcupine meat in the scope of nutrition values and the positive effects for health if it is consumed. Also, it is vital to establish marketing strategy, provide ready cooked meat in restaurants and pre-cooked food in packages, setting a reasonable price and improve the quality of the meat in term of attractiveness shall also be emphasised. Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank everyone who has fully supported and collaborated in the research study. References 1. Andersen, H. J., Oksbjerg, N., Young, J. F. and Therkildsen, M. (2005). Feeding and meat quality a future approach. Meat Science 70,543-554. 2. Anonymous. (2006). Halatuju dan teras utama pembangunan sektor pertanian. Sub-sektorternakan. http://www.sabah. gov.my/hwan/download/ Halatuju Ternak.pdf. 3. Anonymous. (2007). Semenanjung Malaysia: Bilangan Aneka Ternakan 2003 dan 2004. http://agrolink.moa.my /jph/dvs/statistics/statidx.html. 4. Becker, T., Benner, E. and Glitsch, K. (1998). Summary report on consumer behaviour towards meat in Germany, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Sweden and The United Kingdom.http://www.unihohenheim.de/~apo420b/euresearch/euwelcome.htm. 5. Becker, T., Benner, E. and Glitsch, K. (2000). Consumer perception of fresh meat quality in Germany. British Food Journal 102(3):246-266. 6. Dahlan and Noor Farizan. (2000). Integrated production system for deer farming in Malaysia. Quality of venison. Research Bulletin Faculty of Agriculture UPM 7(1):23-28. 7. Dransfield, E., Zamora, F. and Bayle, M.C. (1998). Consumer selection of steaks as influenced by information and

76

Health and the Environment Journal, 2012, Vol. 3, No. 1

price index. Food Quality Preference, 9(5):321-326.

and

8. Enser, M. (2001).The role of fat in human nutrition. In B. Rossell, Oil and fat, Vol. 2. Animal carcass fat, (pp. 197215). UK: Wallingford. 9. Gale E. W., Bruno L., Shanon L. S. and Chedlia T. (2000). Explaining Stated Importance of Production Process, Color and Price in Quebec Veal Meat Purchases. The 2000 proceedings of the 46th annual conference. Consumer interests annual46. http://www. consumerinterests.org/i4a/pages/index.cf m?pageid=3420 10. Given, D.I, Kliem, K.E. and Gibbs. R.A. (2006). The role of meat as a source of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the human diet. Meat Science 74:209-218. 11. Gossard, M. Hill and York, R. (2003). Social structural influences on meat consumption. Human Ecology Review 10(1):1-9. 12. Grunert, K.G. (2006). Future trends and consumer lifestyles with regard to meat consumption. Meat Science, 74:149-160. 13. Harrington, G. (1994). Consumer demands: Major problems facing industry in a consumer-driven society. Meat Science 36:5-18. 14. Hoffman, L.C. and Bigalke, R.C. (1999). Utilising wild ungulates from southern Africa for meat production: Potential research requirements for the new millennium. Proceedings of the 37th Congress of the Wildlife Management Association of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa.

15. Hoffman, L.C.(2000). The yield and chemical composition of impala (Aepyceros melampus), a South African antelope species. J. Sci. Fd. & Agric 80(6):752756. 16. Hoffman, L.C. (2001). The effect of different culling methodologies on the physical meat quality attributes of various game species. In: H. Ebedes, B. Reilly, W. van Hoven and B. Penzhorn (Eds), Sustainable utilisation Conservation in practice, pp. 7886. Pretoria: Wildlife Decision Support Services. 17. Hoffman, L.C., Crafford, K., Muller, M. and Schutte, D.W. (2003). Perceptions and consumption of game meat by a group of tourists visiting South Africa. South African Journal of Wildlife Research 33:125-130. 18. Hoffman, L. C., Muller, M., Schutte, De W. and Crafford, K. (2004). The retail of South African game meat: Current trade and marketing trends. South African Journal of Wildlife Research 34(2): 123134. 19. Hoffman, L.C., Kritzinger, B. and Ferreira, A.V. (2005). The effects of region and gender on the fatty acid, amino acid, mineral, myoglobin and collagen contents of impala (Aepyceros melampus) meat. Meat Science 69:551558. 20. Hoffman, L.C. and Wiklund, E. (2006). Game and venison-meat for the modern consumer. Meat Science 74:197-208. 21. Norsuhana A.H., Shukor Md.Nor. and Aminah A. (2008). Pengambilan daging oleh pengguna Lembah Klang, Malaysia. Jurnal Pengguna 11:29-41. 77

Health and the Environment Journal, 2012, Vol. 3, No. 1

22. Norsuhana, A.H., Shukor Md. Nor., Sazili, A.Q., Aminah A. and Zainal Zahari Z. (2007). The effects of commercial pellets on feed intake, digestibility and nutrient composition in meat of Malayan porcupine (Hystrix brachyura). Prooceeding 9th Symposium of the Malaysian Society of Applied Biology (pp 88-91). 23. Nor, Z. N. (2003). Perak terus rintis ternakan rusa. Utusan Malaysia15 Mei 2003. http://www.jphpk.gov.my/ Malay/Mei03%2015a.htm.(Retrieved on 3May,2011). 24. Radder, L. and Roux, R. le. (2005). Factors food choice in relation to venison: A South African example. Meat Science 71:583-589. 25. Richardson, N.J., MacFie, H.J.H. and R. Shepherd. (1994). Consumer attitudes to meat eating. Meat Science 36:57-65. 26. Russell, C.G. and Cox, D.N. (2004). Understanding middle-aged consumers perceptions of meat using repertory grid methodology. Food Quality and Preferences 15:317-329. 27. Santos, M.L.S. and Booth, D.A. (1996). Influences on meat avoidance among British students. Appetite 27: 197-205.

28. SPSS. (2002) User guide SPSS Inc. Headquarters, 233 S. Wacker Drive, 11th floor Chicago, Illinois 60606 http://www.spss.com/press/template_vie w.cfm?PR_ID=547. 29. Wildlife Ordinance Malaysia. (1972). Akta Perlindungan Hidupan Liar. Akta 76,12 Ogos 2006. http://www. wildlife. gov.my/webpagev3_english/akta/Akta_7 6.pdf. 30. Wilkie, D.S., Starkey, M., Abernethy, K., Nstame Eva, E., Telfer, P. and Godoy, R. (2005). Role of prices and wealth in consumer demand for bushmeat in Gabon, Central Africa. Conservation Biology 19:268-274. 31. Williamson, C.S., Foster, R.K., Stanner, R.K. and Buttriss, J.L. (2005). Red meat in the diet. Nutrition Bulletin 30:323355. 32. Zainal, Z. Z. (1998). The breeding and Production of the Malayan Porcupine (Hystrix brachyura):A potential for commercial breeding venture. The Journal of Wildlife and Parks 16:145-148. 33. Zotte, A.D. (2002) . Perception of rabbit meat quality and major factors influencing the rabbit carcass and meat quality. Livestock Production Sience 75: 11-32.

78

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Factors Influencing Consumers' Preferences Towards Meat and Meat ProductsDocument8 paginiFactors Influencing Consumers' Preferences Towards Meat and Meat ProductshafizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abstract: Although The Halal Concept Has Not Been A Major ElementDocument6 paginiAbstract: Although The Halal Concept Has Not Been A Major ElementAdnin ZayanieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consumer Behaviour Related To Rabbit Meat As Functional FoodDocument13 paginiConsumer Behaviour Related To Rabbit Meat As Functional FoodUmar GondalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Non-Muslims' Awareness of Halal Principles and Related Food Products in MalaysiaDocument8 paginiNon-Muslims' Awareness of Halal Principles and Related Food Products in MalaysiaxuyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wong and Aini 2017Document12 paginiWong and Aini 2017Marcos RodriguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 PDFDocument8 pagini2 PDFPurshotam GovindÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review of Related Literature Native PigDocument27 paginiReview of Related Literature Native Pigsegsyyapril0729Încă nu există evaluări

- Consumers' Purchasing Behavior Towards Fresh Meat in Davao City, PhilippinesDocument15 paginiConsumers' Purchasing Behavior Towards Fresh Meat in Davao City, Philippinesgreta tanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kem LarawanDocument31 paginiKem Larawangrace100% (1)

- An Analysis of Meat Demand in Akungba-Akoko, Nigeria: July 2013Document10 paginiAn Analysis of Meat Demand in Akungba-Akoko, Nigeria: July 2013Olapade BabatundeÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Structural Equation Model of The Factors Influencing British Consumers' Behaviour Towards Animal WelfareDocument13 paginiA Structural Equation Model of The Factors Influencing British Consumers' Behaviour Towards Animal Welfaresanthoshkumark20026997Încă nu există evaluări

- Producers' and Consumers' Preferences and Perceptions For Pig Breeding Traits and Quality of Pork Meat in BatangasDocument17 paginiProducers' and Consumers' Preferences and Perceptions For Pig Breeding Traits and Quality of Pork Meat in Batangasedwin alcantaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shan - Consumer Evaluations of Processed Meat Products Reformulated To Be HealthierDocument8 paginiShan - Consumer Evaluations of Processed Meat Products Reformulated To Be HealthierMarcos RodriguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consumer S Preference Towards Organic Food ProductsDocument5 paginiConsumer S Preference Towards Organic Food ProductsRamasamy Velmurugan100% (2)

- Chapter 1 GELODocument20 paginiChapter 1 GELOShirley Delos ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of White Meat Consumption Patterns Among Staff of University of IbadanDocument13 paginiAnalysis of White Meat Consumption Patterns Among Staff of University of IbadanUmar GondalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Food Safety Knowledge, Attitude and Hygiene Practices Among The Street Food Vendors in Northern Kuching City, SarawakDocument9 paginiFood Safety Knowledge, Attitude and Hygiene Practices Among The Street Food Vendors in Northern Kuching City, SarawakFidya Ardiny50% (2)

- Organic Food Market Trend and Consumers' Profile in Phnom Penh City, CambodiaDocument8 paginiOrganic Food Market Trend and Consumers' Profile in Phnom Penh City, CambodiaAnonymous bWd6ZgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research On Pre-Slaughter Stress and Meat Quality - A Review of CHDocument7 paginiResearch On Pre-Slaughter Stress and Meat Quality - A Review of CHFikadu GadisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3857 15606 1 PB PDFDocument14 pagini3857 15606 1 PB PDFTriston LiongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moringa OleiferaDocument3 paginiMoringa Oleiferawakaioni24Încă nu există evaluări

- LimpopoDocument19 paginiLimpopoisaacbwalya433Încă nu există evaluări

- Analisis Perilaku Konsumen Pada Pembelian Daging BabiDocument15 paginiAnalisis Perilaku Konsumen Pada Pembelian Daging BabiMaikhel Abraham100% (1)

- IJV25886621Document7 paginiIJV25886621jurnal agrosainsÎncă nu există evaluări

- When The First of The 5Fs For The Welfare of Dogs Goes Wrong.Document14 paginiWhen The First of The 5Fs For The Welfare of Dogs Goes Wrong.Glaucia BrandãoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project Rationale: 1.1 Statement of The ProblemDocument7 paginiProject Rationale: 1.1 Statement of The ProblemArianne BatallonesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Halal Meat: A Niche Product in The Food MarketDocument7 paginiHalal Meat: A Niche Product in The Food MarketMuhminHassanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foods: Role of Sensory Evaluation in Consumer Acceptance of Plant-Based Meat Analogs and Meat Extenders: A Scoping ReviewDocument15 paginiFoods: Role of Sensory Evaluation in Consumer Acceptance of Plant-Based Meat Analogs and Meat Extenders: A Scoping ReviewTất Tính ĐạtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motivations ManuscriptDocument44 paginiMotivations ManuscriptNHUNG NGÔ THỊ HOÀIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Olmedilla Alonso2013Document12 paginiOlmedilla Alonso2013mekdes abebeÎncă nu există evaluări

- A S F C S: Nimal Ourced Oods and Hild TuntingDocument18 paginiA S F C S: Nimal Ourced Oods and Hild Tuntingchandra dewiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Knowledge On Halal Food Amongst Food Industry Entrepreneurs in MalaysiaDocument7 paginiKnowledge On Halal Food Amongst Food Industry Entrepreneurs in MalaysiaDwiNegoroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review KotorDocument3 paginiReview KotorKelompok 1Încă nu există evaluări

- Foods 09 00546Document10 paginiFoods 09 00546armaan aliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaDocument10 paginiAssessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaAlexander DeckerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Draghici Et AlDocument9 paginiDraghici Et AlCristina NicolaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Farmers Markets QualityDocument44 paginiFarmers Markets QualityvasaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- 391 1885 1 PB PDFDocument21 pagini391 1885 1 PB PDFMikoÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHAPTER 1 by Grade 12Document11 paginiCHAPTER 1 by Grade 12Kurt Marvin4Încă nu există evaluări

- Meat Industry Development in Nigeria Implications of The Consumers Perspective PDFDocument17 paginiMeat Industry Development in Nigeria Implications of The Consumers Perspective PDFOlapade BabatundeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liljenstolpe 2010Document18 paginiLiljenstolpe 2010Tuyen TietÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ion, 2007. Reasons Why People Turn To Vegetarian DietDocument6 paginiIon, 2007. Reasons Why People Turn To Vegetarian DietDaniela RoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Food Security Related ThesisDocument4 paginiFood Security Related Thesismichelethomasreno100% (2)

- Foods Expers Mental Perspectives 7th Edition Mcwilliams Test BankDocument11 paginiFoods Expers Mental Perspectives 7th Edition Mcwilliams Test BankHeatherGoodwinyaine100% (16)

- Ecological Economics: Ingrid Moons, Camilla Barbarossa, Patrick de PelsmackerDocument11 paginiEcological Economics: Ingrid Moons, Camilla Barbarossa, Patrick de PelsmackerSathish SmartÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critique Report 1Document7 paginiCritique Report 1VENTURA, ANNIE M.Încă nu există evaluări

- 2011 Animal Products SurveyDocument26 pagini2011 Animal Products SurveyRadu Victor TapuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Special Topics in Animal ScienceDocument10 paginiSpecial Topics in Animal ScienceIvan Jhon AnamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Constraints Perceived by Farmers in Adopting Scientific Dairy Farming Practices in Madhuni District of BiharDocument4 paginiConstraints Perceived by Farmers in Adopting Scientific Dairy Farming Practices in Madhuni District of BiharAjay Yadav100% (1)

- Consumer S Preference Towards Organic Food Products: Rupesh Mervin M and Dr. R. VelmuruganDocument5 paginiConsumer S Preference Towards Organic Food Products: Rupesh Mervin M and Dr. R. VelmuruganGousia SiddickÎncă nu există evaluări

- ShivaDocument36 paginiShivashivaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Survey of Pet Feeding Practices of Dog Owners VIDocument11 paginiA Survey of Pet Feeding Practices of Dog Owners VINatala WillzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Lab-Grown Meat in The FMCG Sector.Document10 paginiImpact of Lab-Grown Meat in The FMCG Sector.lakshya khandelwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Healthier Meat and Meat Products: Their Role As Functional FoodsDocument10 paginiHealthier Meat and Meat Products: Their Role As Functional Foodsamelia arum ramadhaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Halal PDFDocument8 paginiHalal PDFMuhammad Hazman HusinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Animals 12 00678Document27 paginiAnimals 12 00678Amanullah ZubairÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Consumers' Perception of Lamb Meat Using Free Word AssociationDocument7 paginiUnderstanding Consumers' Perception of Lamb Meat Using Free Word AssociationHuy CaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economics of Farm Animal Welfare, The: Theory, Evidence and PolicyDe la EverandEconomics of Farm Animal Welfare, The: Theory, Evidence and PolicyBouda Vosough AhmadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- PeralatanDocument1 paginăPeralatankebajikan7972Încă nu există evaluări

- AlkaloidsDocument71 paginiAlkaloidskebajikan7972Încă nu există evaluări

- Trends in Analytical Chemistry: Agapios Agapiou, Anton Amann, Pawel Mochalski, Milt Statheropoulos, C.L.P. ThomasDocument18 paginiTrends in Analytical Chemistry: Agapios Agapiou, Anton Amann, Pawel Mochalski, Milt Statheropoulos, C.L.P. Thomaskebajikan7972Încă nu există evaluări

- Daily AwradDocument1 paginăDaily Awradkebajikan7972Încă nu există evaluări

- Artificial Intelligence With SCILABDocument4 paginiArtificial Intelligence With SCILABkebajikan7972Încă nu există evaluări

- Amino Acid Analysis Using ZORBAX Eclipse AAA ColumnsDocument10 paginiAmino Acid Analysis Using ZORBAX Eclipse AAA ColumnsMuhammad KhairulnizamÎncă nu există evaluări

- 75 Duas From The QuranDocument23 pagini75 Duas From The Quranislamicduaa92% (211)

- Insert Paper English Cambridge Checkpoint 2018Document4 paginiInsert Paper English Cambridge Checkpoint 2018brampok86% (7)

- Brain Imaging Technologies and Their Applications in NeuroscienceDocument45 paginiBrain Imaging Technologies and Their Applications in NeuroscienceNeea AvrielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Suzy and Leah Reading GuideDocument15 paginiSuzy and Leah Reading Guideapi-260353457100% (1)

- Jaundice in Cultured Hybrid Catfish Clarias BetracDocument6 paginiJaundice in Cultured Hybrid Catfish Clarias BetracLeeinda100% (1)

- Ustrasana - Camel Pose - Yoga International PDFDocument8 paginiUstrasana - Camel Pose - Yoga International PDFToreØrnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 7 TG SCIENCE 2nd QuarterDocument60 paginiGrade 7 TG SCIENCE 2nd QuarterAilyn Soria Ecot100% (2)

- How To Analyze People Uncover Sherlock Ho - Patrick LightmanDocument69 paginiHow To Analyze People Uncover Sherlock Ho - Patrick LightmanRuney DuloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Describing How Muscles Work Activity SheetDocument3 paginiDescribing How Muscles Work Activity SheetTasnim MbarkiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Equus PDFDocument8 paginiEquus PDFcfeauxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alphabet ColoringDocument27 paginiAlphabet ColoringMay100% (1)

- Foto Polos Abdomen - PPTX William Bunga DatuDocument39 paginiFoto Polos Abdomen - PPTX William Bunga DatuWilliam Bunga DatuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prohibited & Restricted Item For IndonesiaDocument13 paginiProhibited & Restricted Item For IndonesiaAhmad AmirudinÎncă nu există evaluări

- PATH - Acute Kidney InjuryDocument12 paginiPATH - Acute Kidney InjuryAyyaz HussainÎncă nu există evaluări

- English GrammarDocument29 paginiEnglish GrammarJohn CarloÎncă nu există evaluări

- FAR - Biological AssetsDocument1 paginăFAR - Biological AssetsJun JunÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human Beings Are Complex OrganismDocument2 paginiHuman Beings Are Complex OrganismerneeyashÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annotated Reading LogDocument13 paginiAnnotated Reading LoggaureliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Forgotten Realms Archetypes Savagery & Shadow (11293249) PDFDocument55 paginiForgotten Realms Archetypes Savagery & Shadow (11293249) PDFMark Avrit100% (12)

- The Effects of Deforestation On Wildlife Along The Transamazon HighwayDocument8 paginiThe Effects of Deforestation On Wildlife Along The Transamazon HighwayCleber Dos SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Level H - Animals AnimalsDocument16 paginiLevel H - Animals AnimalsPhạm Thị Hồng ThuÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Power of NetworkingDocument12 paginiThe Power of Networkingapi-400197296Încă nu există evaluări

- Westside Deli MenuDocument6 paginiWestside Deli MenuCharlestonCityPaperÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Werewolf in The Crested KimonoDocument17 paginiThe Werewolf in The Crested KimonoEstrimerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Codex Siberys-1-6Document6 paginiCodex Siberys-1-6gabiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Use and Non-Use of Articles: From The Purdue University Online Writing Lab, Http://owl - English.purdue - EduDocument2 paginiThe Use and Non-Use of Articles: From The Purdue University Online Writing Lab, Http://owl - English.purdue - EduprasanthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ket Exam 1 ReadingDocument10 paginiKet Exam 1 ReadingFranciscaBalasSuarezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tugas Leo WahyuDocument3 paginiTugas Leo WahyuChowa RemiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Akin To PityDocument356 paginiAkin To PityPaul StewartÎncă nu există evaluări

- We'Re Going On A Bear HuntDocument5 paginiWe'Re Going On A Bear HuntMaria BÎncă nu există evaluări

- Equine Reproductive Physiology, Breeding, and Stud ManagementDocument383 paginiEquine Reproductive Physiology, Breeding, and Stud Managementfrancisco_aguiar_22100% (2)