Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Abbas Kiarostami

Încărcat de

philip cardonDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Abbas Kiarostami

Încărcat de

philip cardonDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Abbas Kiarostami (Persian: ???? ?????????

;[1] born 22 June 1940) is an Iranian f ilm director, screenwriter, photographer and film producer.[2][3][4] An active f ilmmaker since 1970, Kiarostami has been involved in over forty films, including shorts and documentaries. Kiarostami attained critical acclaim for directing th e Koker Trilogy (1987 94), Close-Up (1990), Taste of Cherry (1997) (awarded Palme d'Or at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival), and The Wind Will Carry Us (1999). In hi s recent films, Certified Copy (2010) and Like Someone in Love (2012), he filmed for the first time outside Iran, in Italy and Japan, respectively. Kiarostami has worked extensively as a screenwriter, film editor, art director a nd producer and has designed credit titles and publicity material. He is also a poet, photographer, painter, illustrator, and graphic designer. He is part of a generation of filmmakers in the Iranian New Wave, a Persian cinema movement that started in the late 1960s and includes pioneering directors such as Forough Far rokhzad, Sohrab Shahid Saless, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Bahram Beizai, and Parviz Kimi avi. These filmmakers share many common techniques including the use of poetic d ialogue and allegorical storytelling dealing with political and philosophical is sues.[5] Kiarostami has a reputation for using child protagonists, for documentary-style narrative films,[6] for stories that take place in rural villages, and for conve rsations that unfold inside cars, using stationary mounted cameras. He is also k nown for his use of contemporary Iranian poetry in the dialogue, titles, and the mes of his films. Contents [hide] 1 Early life and background 2 Personal life 3 Film career 3.1 1970s 3.2 1980s 3.3 1990s 3.4 2000s 3.5 2010s 3.6 Film festival work 4 Cinematic style 4.1 Individualism 4.2 Fiction and non-fiction 4.3 Themes of life and death 4.4 Visual and audio techniques 4.5 Poetry and imagery 4.6 Spirituality 5 Poetry, art and photography 6 Reception and criticism 6.1 Honors and awards 7 Filmography 8 Books by Kiarostami 9 References 10 Bibliography 11 External links Early life and background[edit] Kiarostami majored in painting and graphic design at the University of Tehran Co llege of Fine Arts. Kiarostami was born in Tehran. His first artistic experience was painting, which he continued into his late teens, winning a painting competition at the age of 18 shortly before he left home to study at the University of Tehran School of Fi ne Arts.[7] He majored in painting and graphic design, and supported his studies by working as a traffic policeman.

As a painter, designer, and illustrator, Kiarostami worked in advertising in the 1960s, designing posters and creating commercials. Between 1962 and 1966, he sh ot around 150 advertisements for Iranian television. In the late 1960s, he began creating credit titles for films (including Gheysar by Masoud Kimiai) and illus trating children's books.[7][8] Personal life[edit] In 1969, Abbas married Parvin Amir-Gholi. They had two sons, Ahmad (born 1971) a nd Bahman (1978). They divorced in 1982. At the age of 15, Bahman Kiarostami wor ked as a director and cinematographer in making the documentary Journey to the L and of the Traveller (1993). Kiarostami was one of the few directors who remained in Iran after the 1979 revo lution, when many of his peers fled the country. He believes that it was one of the most important decisions of his career. His permanent base in Iran and his n ational identity have consolidated his ability as a filmmaker: "When you take a tree that is rooted in the ground, and transfer it from one pla ce to another, the tree will no longer bear fruit. And if it does, the fruit wil l not be as good as it was in its original place. This is a rule of nature. I th ink if I had left my country, I would be the same as the tree." Abbas Kiarostami[ 9] Kiarostami frequently wears dark spectacles or sunglasses. He needs them as he h as a sensitivity to light.[10] Film career[edit] Kiarostami in 1977 1970s[edit] In 1969, when the Iranian New Wave began with Dariush Mehrjui's film Gav, Kiaros tami helped set up a filmmaking department at the Institute for Intellectual Dev elopment of Children and Young Adults (Kanun) in Tehran. Its debut production an d Kiarostami's first film was the twelve-minute The Bread and Alley (1970), a ne o-realistic short film about a schoolboy's confrontation with an aggressive dog. Breaktime followed in 1972. The department became one of Iran's most noted film studios, producing not only Kiarostami's films, but acclaimed Persian films suc h as The Runner and Bashu, the Little Stranger.[7] In the 1970s, Kiarostami pursued an individualistic style of film making.[11] Wh en discussing his first film, he stated: "Bread and Alley was my first experience in cinema and I must say a very difficu lt one. I had to work with a very young child, a dog, and an unprofessional crew except for the cinematographer, who was nagging and complaining all the time. W ell, the cinematographer, in a sense, was right because I did not follow the con ventions of film making that he had become accustomed to."[12] Following The Experience (1973), Kiarostami released The Traveler (Mossafer) in 1974. The Traveler tells the story of Qassem Julayi, a troubled and troublesome boy from a small Iranian city. Intent on attending a football match in far-off T ehran, he scams his friends and neighbors to raise money, and journeys to the st adium in time for the game, only to meet with an ironic twist of fate. In addres sing the boy's determination to reach his goal, alongside his indifference to th e effects of his amoral actions, the film examined human behavior and the balanc e of right and wrong. It furthered Kiarostami's reputation for realism, diegetic simplicity, and stylistic complexity, as well as his fascination with physical and spiritual journeys.[13]

In 1975, Kiarostami directed two short films So Can I and Two Solutions for One Problem. In early 1976, he released Colors, followed by the fifty-four minute fi lm A Wedding Suit, a story about three teenagers coming into conflict over a sui t for a wedding.[14][15] Kiarostami's first feature film was the 112-minute Report (1977). It revolved ar ound the life of a tax collector accused of accepting bribes; suicide was among its themes. In 1979, he produced and directed First Case, Second Case. 1980s[edit] In the early 1980s, Kiarostami directed several short films including Toothache (1980), Orderly or Disorderly (1981), and The Chorus (1982). In 1983, he directe d Fellow Citizen. It was not until his release of Where Is the Friend's Home? th at he began to gain recognition outside Iran. The film tells a simple account of a conscientious eight-year-old schoolboy's qu est to return his friend's notebook in a neighboring village lest his friend be expelled from school. The traditional beliefs of Iranian rural people are portra yed. The film has been noted for its poetic use of the Iranian rural landscape a nd its realism, both important elements of Kiarostami's work. Kiarostami made th e film from a child's point of view.[16][17] Where Is the Friend's Home?, And Life Goes On (1992) (also known as Life and Not hing More), and Through the Olive Trees (1994) are described by critics as the K oker trilogy, because all three films feature the village of Koker in northern I ran. The films also relate to the 1990 Manjil-Rudbar earthquake, in which 40,000 people lost their lives. Kiarostami uses the themes of life, death, change, and continuity to connect the films. The trilogy was successful in France in the 19 90s and other Western European countries such as the Netherlands, Sweden, German y and Finland.[18] But, Kiarostami does not consider the three films to comprise a trilogy. He has suggested that the last two titles plus Taste of Cherry (1997 ) comprise a trilogy, given their common theme of the preciousness of life.[19] In 1987, Kiarostami was involved in the screenwriting of The Key, which he edite d but did not direct. In 1989, he released Homework. 1990s[edit] Kiarostami-1940.jpg Kiarostami's first film of the decade was Close-Up (1990), which narrates the st ory of the real-life trial of a man who impersonated film-maker Mohsen Makhmalba f, conning a family into believing they would star in his new film. The family s uspects theft as the motive for this charade, but the impersonator, Hossein Sabz ian, argues that his motives were more complex. The part-documentary, part-stage d film examines Sabzian's moral justification for usurping Makhmalbaf's identity , questioning his ability to sense his cultural and artistic flair.[20][21] Rank ed #42 in British Film Institute's The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time, CloseUp received praise from directors such as Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, We rner Herzog, Jean-Luc Godard, and Nanni Moretti[22] and was released across Euro pe.[23] In 1992, Kiarostami directed Life, and Nothing More..., regarded by critics as t he second film of the Koker trilogy. The film follows a father and his young son as they drive from Tehran to Koker in search of two young boys who they fear mi ght have perished in the 1990 earthquake. As the father and son travel through t he devastated landscape, they meet earthquake survivors forced to carry on with their lives amid disaster.[24][25][26] That year Kiarostami won a Prix Roberto R ossellini, the first professional film award of his career, for his direction of the film. The last film of the so-called Koker trilogy was Through the Olive Tr ees (1994), which expands a peripheral scene from Life and Nothing More into the

central drama.[27] Critics such as Adrian Martin have called the style of filmm aking in the Koker trilogy as "diagrammatical", linking the zig-zagging patterns in the landscape and the geometry of forces of life and the world.[28][29] A fl ashback of the zigzag path in Life and Nothing More... (1992) in turn triggers t he spectator's memory of the previous film, Where Is the Friend's Home? from 198 7, shot before the earthquake. This symbolically links to the post-earthquake re construction in Through the Olive Trees in 1994. In 1995, Miramax Films released Through the Olive Trees in the US theaters. Kiarostami next wrote the screenplays for The Journey and The White Balloon (199 5), for his former assistant Jafar Panahi.[7] Between 1995 and 1996, he was invo lved in the production of Lumire and Company, a collaboration with 40 other film directors. Kiarostami won the Palme d'Or (Golden Palm) award at the Cannes Film Festival fo r Taste of Cherry.[30] It is the drama of a man, Mr. Badii, determined to commit suicide. The film involved themes such as morality, the legitimacy of the act o f suicide, and the meaning of compassion.[31] Kiarostami directed The Wind Will Carry Us in 1999, which won the Grand Jury Pri ze (Silver Lion) at the Venice International Film Festival. The film contrasted rural and urban views on the dignity of labor, addressing themes of gender equal ity and the benefits of progress, by means of a stranger's sojourn in a remote K urdish village.[18] An unusual feature of the movie is that many of the characte rs are heard but not seen; at least thirteen to fourteen speaking characters in the film are never seen.[32] 2000s[edit] In 2000, at the San Francisco Film Festival award ceremony, Kiarostami was award ed the Akira Kurosawa Prize for lifetime achievement in directing, but surprised everyone by giving it away to veteran Iranian actor Behrooz Vossoughi for his c ontribution to Iranian cinema.[33][34] In 2001, Kiarostami and his assistant, Seifollah Samadian, traveled to Kampala, Uganda at the request of the United Nations International Fund for Agricultural Development, to film a documentary about programs assisting Ugandan orphans. He stayed for ten days and made ABC Africa. The trip was originally intended as a r esearch in preparation for the filming, but Kiarostami ended up editing the enti re film from the video footage shot there.[35] The high number of orphans in Uga nda has resulted from the deaths of parents in the AIDS epidemic. Time Out editor and National Film Theatre chief programmer, Geoff Andrew, said i n referring to the film: "Like his previous four features, this film is not abou t death but life-and-death: how they're linked, and what attitude we might adopt with regard to their symbiotic inevitability."[36] The following year, Kiarostami directed Ten, revealing an unusual method of film making and abandoning many scriptwriting conventions.[32] Kiarostami focused on the socio-political landscape of Iran. The images are seen through the eyes of o ne woman as she drives through the streets of Tehran over a period of several da ys. Her journey is composed of ten conversations with various passengers, which include her sister, a hitchhiking prostitute, and a jilted bride and her demandi ng young son. This style of filmmaking was praised by a number of critics. A. O. Scott in The New York Times wrote that Kiarostami, "in addition to being p erhaps the most internationally admired Iranian filmmaker of the past decade, is also among the world masters of automotive cinema...He understands the automobi le as a place of reflection, observation and, above all, talk."[37] In 2003, Kiarostami directed Five, a poetic feature with no dialogue or characte

rization. It consists of five long shots of nature which are single-take sequenc es, shot with a hand-held DV camera, along the shores of the Caspian Sea. Althou gh the film lacks a clear storyline, Geoff Andrew argues that the film is "more than just pretty pictures". He adds, "Assembled in order, they comprise a kind o f abstract or emotional narrative arc, which moves evocatively from separation a nd solitude to community, from motion to rest, near-silence to sound and song, l ight to darkness and back to light again, ending on a note of rebirth and regene ration."[38] He notes the degree of artifice concealed behind the apparent simpl icity of the imagery. Kiarostami produced 10 on Ten (2004), a journal documentary that shares ten less ons on movie-making while he drives through the locations of his past films. The movie is shot on digital video with a stationary camera mounted inside the car, in a manner reminiscent of Taste of Cherry and Ten. In 2005 and 2006, he direct ed The Roads of Kiarostami, a 32-minute documentary that reflects on the power o f landscape, combining austere black-and-white photographs with poetic observati ons,[39] engaging music with political subject matter. Also in 2005, Kiarostami contributed the central section to Tickets, a portmanteau film set on a train tr aveling through Italy. The other segments were directed by Ken Loach and Ermanno Olmi. In 2008, Kiarostami directed the feature Shirin, which features close-ups of man y notable Iranian actresses and the French actress Juliette Binoche as they watc h a film based on a partly mythological Persian romance tale of Khosrow and Shir in, with themes of female self-sacrifice.[40][41] The film has been described as "a compelling exploration of the relationship between image, sound and female s pectatorship."[39] 2010s[edit] Certified Copy (2010), again starring Juliette Binoche, was made in Tuscany and was Kiarostami's first film to be shot and produced outside Iran.[39] The story of an encounter between a British man and a French woman, it was entered in comp etition for the Palme d'Or in the 2010 Cannes Film Festival. Peter Bradshaw of T he Guardian describes the film as an "intriguing oddity", and said, "'Certified Copy' is the deconstructed portrait of a marriage, acted with well-intentioned f ervour by Juliette Binoche, but persistently baffling, contrived, and often simp a highbrow misfire of the most peculiar sort."[42] He concluded that ly bizarre the film is "unmistakably an example of Kiarostami's compositional technique, th ough not a successful example."[42] Roger Ebert, however, praised the film, noti ng that "Kiarostami is rather brilliant in the way he creates offscreen spaces." [43] Binoche won the Best Actress Award at Cannes for her performance in the fil m. Kiarostami's next, Like Someone in Love, set and shot in Japan, received mixe d reviews and even some pans upon its premiere at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival. Film festival work[edit] Kiarostami (left) at the Estoril Film Festival in 2010 Kiarostami has been a jury member at numerous film festivals, most notably the C annes Film Festival in 1993, 2002 and 2005. He was also the president of the Camr a d'Or Jury in Cannes Film Festival 2005. He has been announced as the president of the Cinfondation and short film sections of the 2014 Cannes Film Festival.[44 ] Other representatives include the Venice Film Festival in 1985, the Locarno Inte rnational Film Festival in 1990, the San Sebastian International Film Festival i n 1996, the So Paulo International Film Festival in 2004, the Capalbio Cinema Fes tival in 2007 (in which he was president of the jury), and the Kstendorf Film and Music Festival in 2011.[45][46][47] He also makes regular appearances at many o ther film festivals across Europe, including the Estoril Film Festival in Portug

al. Cinematic style[edit] Main article: Cinematic style of Abbas Kiarostami Individualism[edit] Though Kiarostami has been compared to Satyajit Ray, Vittorio de Sica, ric Rohmer , and Jacques Tati, his films exhibit a singular style, often employing techniqu es of his own invention.[7] During the filming of The Bread and Alley in 1970, Kiarostami had major differen ces with his experienced cinematographer about how to film the boy and the attac king dog. While the cinematographer wanted separate shots of the boy approaching , a close-up of his hand as he enters the house and closes the door, followed by a shot of the dog, Kiarostami believed that if the three scenes could be captur ed as a whole it would have a more profound impact in creating tension over the situation. That one shot took around forty days to complete, until Kiarostami wa s fully content with the scene. Kiarostami later commented that the breaking of scenes would have disrupted the rhythm and content of the film's structure, pref erring to let the scene flow as one.[12] Unlike other directors, Kiarostami has showed no interest in staging extravagant combat scenes or complicated chase scenes in large-scale productions, instead a ttempting to mold the medium of film to his own specifications.[48] Kiarostami a ppeared to have settled on his style with the Koker trilogy, which included a my riad of references to his own film material, connecting common themes and subjec t matter between each of the films. Stephen Bransford has contended that Kiarost ami's films do not contain references to the work of other directors, but are fa shioned in such a manner that they are self-referenced. Bransford believes his f ilms are often fashioned into an ongoing dialectic with one film reflecting on a nd partially demystifying an earlier film.[27] He has continued experimenting with new modes of filming, using different direct orial methods and techniques. A case in point is Ten, which was filmed in a movi ng automobile in which Kiarostami was not present. He gave suggestions to the ac tors about what to do, and a camera placed on the dashboard filmed them while th ey drove around Tehran.[12][49] The camera was allowed to roll, capturing the fa ces of the people involved during their daily routine, using a series of extreme -close shots. Ten was an experiment that used digital cameras to virtually elimi nate the director. This new direction towards a digital micro-cinema, is defined as a micro-budget filmmaking practice, allied with a digital production basis.[ 50] Kiarostami's cinema offers a different definition of film. According to film pro fessors such as Jamsheed Akrami of William Paterson University, Kiarostami has c onsistently tried to redefine film by forcing the increased involvement of the a udience. In recent years, he has also progressively trimmed the timespan within his films. Akrami thinks that this reduces the filmmaking from a collective ende avor to a purer, more basic form of artistic expression.[48] Fiction and non-fiction[edit] Kiarostami's films contain a notable degree of ambiguity, an unusual mixture of simplicity and complexity, and often a mix of fictional and documentary elements . Kiarostami has stated, "We can never get close to the truth except through lyi ng."[7][51] The boundary between fiction and non-fiction is significantly reduced in Kiarost ami's cinema.[52] The French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, writing about Kiarostam i, and in particular Life and Nothing More..., has argued that his films are nei ther quite fiction nor quite documentary. Life and Nothing More..., he argues, i s neither representation nor reportage, but rather "evidence":

[I]t all looks like reporting, but everything underscores (indique l'vidence) tha t it is the fiction of a documentary (in fact, Kiarostami shot the film several months after the earthquake), and that it is rather a document about "fiction": not in the sense of imagining the unreal, but in the very specific and precise s ense of the technique, of the art of constructing images. For the image by means of which, each time, each opens a world and precedes himself in it (s'y prcde) is not pregiven (donne toute faite) (as are those of dreams, phantasms or bad films ): it is to be invented, cut and edited. Thus it is evidence, insofar as, if one day I happen to look at my street on which I walk up and down ten times a day, I construct for an instant a new evidence of my street.[53] For Jean-Luc Nancy, this notion of cinema as "evidence", rather than as document ary or imagination, is tied to the way Kiarostami deals with life-and-death (cf. the remark by Geoff Andrew on ABC Africa, cited above, to the effect that Kiaro stami's films are not about death but about life-and-death): Existence resists the indifference of life-and-death, it lives beyond mechanical "life," it is always its own mourning, and its own joy. It becomes figure, imag e. It does not become alienated in images, but it is presented there: the images are the evidence of its existence, the objectivity of its assertion. This thoug ht which, for me, is the very thought of this film [Life and Nothing More...] is a d ifficult thought, perhaps the most difficult. It's a slow thought, always under way, fraying a path so that the path itself becomes thought. It is that which fr ays images so that images become this thought, so that they become the evidence of this thought and not in order to "represent" it.[54] In other words, wanting to accomplish more than just represent life and death as opposing forces, but rather to illustrate the way in which each element of natu re is inextricably linked, Kiarostami has devised a cinema that does more than j ust present the viewer with the documentable "facts," but neither is it simply a matter of artifice. Because "existence" means more than simply life, it is proj ective, containing an irreducibly fictive element, but in this "being more than" life, it is therefore contaminated by mortality. Nancy is giving a clue, in oth er words, toward the interpretation of Kiarostami's statement that lying is the only way to truth.[55][56] Themes of life and death[edit] The concepts of change and continuity, in addition to the themes of life and dea th, play a major role in Kiarostami's works. In the Koker trilogy, these themes play a central role. As illustrated in the aftermath of the 1990 Tehran earthqua ke disaster, they also represent the power of human resilience to overcome and d efy des

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Revised Abbas KiarostamiDocument24 paginiRevised Abbas KiarostamiFaith AmosÎncă nu există evaluări

- A2 Film Portfolio TasksDocument26 paginiA2 Film Portfolio TasksBrian Adrian PapiermanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iranian New Wave Cinema StudyDocument5 paginiIranian New Wave Cinema StudyMuhammadNazimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kiarostami's Unfinished Cinema and Its Postmodern ReflectionsDocument15 paginiKiarostami's Unfinished Cinema and Its Postmodern ReflectionsJennifer Zurita PatronÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Open Image: Poetic Realism and The New Iranian CinemaDocument20 paginiThe Open Image: Poetic Realism and The New Iranian CinemajosepalaciosdelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sculpting in Time With Andrei Tarkovsky PDFDocument4 paginiSculpting in Time With Andrei Tarkovsky PDF65paulosalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kiarostami Contains Separate Essays by Rosenbaum and Saeed-Vafa FollowedDocument20 paginiKiarostami Contains Separate Essays by Rosenbaum and Saeed-Vafa FollowedAjitashaya SinhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sun Yat-sen's Political and Social IdealsDocument24 paginiSun Yat-sen's Political and Social IdealselomavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discussing The Bible With New AgersDocument4 paginiDiscussing The Bible With New AgersServant Of TruthÎncă nu există evaluări

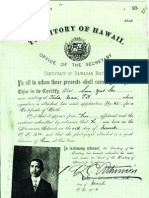

- Sun Yat-Sen: Certification of Live Birth in HawaiiDocument3 paginiSun Yat-Sen: Certification of Live Birth in HawaiiSunYatSenBiography100% (2)

- Questions For Feminist Film StudiesDocument17 paginiQuestions For Feminist Film StudiesNagarajan Vadivel100% (1)

- Eisenstein's Letters To Capra, Ford, Wyler and WellesDocument10 paginiEisenstein's Letters To Capra, Ford, Wyler and WellesJohannes de SilentioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Birth of A NationDocument11 paginiBirth of A NationNavya GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alfonso Cuarón - Senses of CinemaDocument13 paginiAlfonso Cuarón - Senses of Cinemaglakisa100% (1)

- Kim Ki DukDocument6 paginiKim Ki DukRajamohanÎncă nu există evaluări

- World CoursereaderDocument222 paginiWorld CoursereaderKireet PantÎncă nu există evaluări

- Study On Film Noir and German ExpressionismDocument8 paginiStudy On Film Noir and German Expressionismapi-308121334Încă nu există evaluări

- Third Cinema, Trauma and Cinematic IdentityDocument4 paginiThird Cinema, Trauma and Cinematic IdentityPurnaa AanrupÎncă nu există evaluări

- Z.a.B. ZEMAN, Prague Spring - A Report On Czechoslovakia 1968. (1969)Document165 paginiZ.a.B. ZEMAN, Prague Spring - A Report On Czechoslovakia 1968. (1969)ΝΕΟΠΤΟΛΕΜΟΣ ΚΕΡΑΥΝΟΣ 2Încă nu există evaluări

- Screen - Volume 24 Issue 6Document117 paginiScreen - Volume 24 Issue 6Krishn Kr100% (1)

- The French New Wave - Chris Darke (4th Ed)Document28 paginiThe French New Wave - Chris Darke (4th Ed)Kushal BanerjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ladri Di BicicletteDocument6 paginiLadri Di BiciclettePaul PedziwiatrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asian Invasion (Of Multiculturalism) in HollywoodDocument11 paginiAsian Invasion (Of Multiculturalism) in HollywoodMinh-Ha T. PhamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Young Mister LincolnDocument27 paginiYoung Mister LincolnPablo Martínez SamperÎncă nu există evaluări

- Magical Realism in BirdmanDocument18 paginiMagical Realism in BirdmanAjiteSh D SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- La Politique Des Auteurs (Part One)Document15 paginiLa Politique Des Auteurs (Part One)rueda-leonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Free CinemaDocument2 paginiFree CinemaDia AncaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Health in Tamil CinemaDocument6 paginiMental Health in Tamil CinemaNandha KishoreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers Examined as a Commentary on Cultural ViolenceDocument22 paginiOliver Stone's Natural Born Killers Examined as a Commentary on Cultural ViolenceFet BacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Japan Film HistoryDocument10 paginiJapan Film HistoryMrPiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Expressionism in Fellini's WorksDocument2 paginiExpressionism in Fellini's WorksStephanieLDeanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Film Appreciation: Understanding Italian NeorealismDocument7 paginiFilm Appreciation: Understanding Italian NeorealismDebkamal GangulyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Italian NeorealismDocument7 paginiItalian NeorealismAther AhmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Force of Chance - An Interview With Krzysztof Kieślowski - Interviews - Roger Ebert - Reader ViewDocument7 paginiThe Force of Chance - An Interview With Krzysztof Kieślowski - Interviews - Roger Ebert - Reader ViewvarunÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Hollywood 1970sDocument7 paginiNew Hollywood 1970sJohnÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Repr. of Madness in The Shining and Memento (Corr)Document62 paginiThe Repr. of Madness in The Shining and Memento (Corr)Briggy BlankaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biopolitics and The Spectacle in Classic Hollywood CinemaDocument19 paginiBiopolitics and The Spectacle in Classic Hollywood CinemaAnastasiia SoloveiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diagr Secuencias EisensteinnDocument10 paginiDiagr Secuencias EisensteinnA Bao A QuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Film-Literature Encounters MA FilmLit Core ModuleDocument9 paginiFilm-Literature Encounters MA FilmLit Core ModuleAndrew KendallÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Films of Ingmar Bergman - Jesse KalinDocument1 paginăThe Films of Ingmar Bergman - Jesse KalinMario PMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Japanese CinemaDocument2 paginiJapanese Cinemajohnq93Încă nu există evaluări

- Hollywood Dialogue and John Cassavetes' RealismDocument16 paginiHollywood Dialogue and John Cassavetes' Realismjim kistenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Judith Mayne Claire Denis Contemporary Film Directors PDFDocument189 paginiJudith Mayne Claire Denis Contemporary Film Directors PDFSerpilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Akira KurosawaDocument24 paginiAkira KurosawaNHÎncă nu există evaluări

- CT11Document60 paginiCT11bzvzbzvz6185Încă nu există evaluări

- Jean Epstein 'S Cinema of ImmanenceDocument27 paginiJean Epstein 'S Cinema of ImmanenceResat Fuat ÇamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chungking Express PDFDocument8 paginiChungking Express PDFআলটাফ হুছেইনÎncă nu există evaluări

- ST. JAMES ENCYCLOPEDIA: Carl ReinerDocument2 paginiST. JAMES ENCYCLOPEDIA: Carl ReinerAndrew MilnerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Film Critic Philosopher Volume 2 BAZINDocument367 paginiFilm Critic Philosopher Volume 2 BAZINRobert CardulloÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1977 Cine Tracts 1 PDFDocument69 pagini1977 Cine Tracts 1 PDFg_kravaritisÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Auteur TheoryDocument8 paginiThe Auteur Theoryapi-258949253Încă nu există evaluări

- Snow ConversationDocument70 paginiSnow ConversationJordan SchonigÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neale PDFDocument13 paginiNeale PDFpedro fernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- L.A. Noir Gary J. Hausladen and Paul F. StarrsDocument28 paginiL.A. Noir Gary J. Hausladen and Paul F. StarrsIzzy MannixÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essay On Hollywood and PropagandaDocument4 paginiEssay On Hollywood and PropagandaArnold Waswa-IgaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Propnos - Final Draft Compressed1 PDFDocument76 paginiPropnos - Final Draft Compressed1 PDFstordoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bischoff - West African CinemaDocument12 paginiBischoff - West African CinemawjrcbrownÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tributes to American volcanologist Harry GlickenDocument4 paginiTributes to American volcanologist Harry Glickenphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Koppu TaifunDocument3 paginiKoppu Taifunphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- DarlonaddasDocument5 paginiDarlonaddasphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- BirdyDocument10 paginiBirdyphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- DkopffaDocument6 paginiDkopffaphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- SedrwetgweherherherhrehDocument13 paginiSedrwetgweherherherhrehphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- DwopaDocument6 paginiDwopaphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Australian Drama on Surfer's Moral DilemmaDocument2 paginiAustralian Drama on Surfer's Moral Dilemmaphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- DkopaDocument16 paginiDkopaphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- DoalobakaDocument3 paginiDoalobakaphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Winds TonDocument4 paginiWinds Tonphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- DarlonasDocument2 paginiDarlonasphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wildfrid of NorthumbiraDocument11 paginiWildfrid of Northumbiraphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Varnish Book (2012)Document166 paginiThe Varnish Book (2012)crocodylianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mass Effect PsichologtyDocument3 paginiMass Effect Psichologtyphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amagiri IncoerenteDocument5 paginiAmagiri Incoerentephilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hacker Corporate TerrorismDocument3 paginiHacker Corporate Terrorismphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beorthful of Mercia KingDocument4 paginiBeorthful of Mercia Kingphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nnnu WarsDocument3 paginiNnnu Warsphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- KOSOOVCODocument4 paginiKOSOOVCOphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modern Slavery Doc Exposes Human TraffickingDocument6 paginiModern Slavery Doc Exposes Human Traffickingphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- BMW EngineeringDocument1 paginăBMW Engineeringphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philanthropy defined as private initiatives for public good focusing on quality of lifeDocument2 paginiPhilanthropy defined as private initiatives for public good focusing on quality of lifephilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Security and Diplomacy in CHINADocument6 paginiSecurity and Diplomacy in CHINAphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- UruguaaayDocument1 paginăUruguaaayphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- BiographyDocument3 paginiBiographyphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kayser RecordDocument2 paginiKayser Recordphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abdul QuaderDocument5 paginiAbdul Quaderphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- ScientificDocument2 paginiScientificphilip cardonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper 1. The Way of The WorldDocument14 paginiPaper 1. The Way of The WorldSohel Bangi100% (1)

- 11001-1208C Rev B Radar II Velocity SensorDocument10 pagini11001-1208C Rev B Radar II Velocity SensorWily WayerÎncă nu există evaluări

- ĐỀ SỐ 27Document6 paginiĐỀ SỐ 27Khải TrầnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Photograph Lyrics Ed SheeranDocument4 paginiPhotograph Lyrics Ed SheeranALF_1234Încă nu există evaluări

- Invasion of Privacy by Use of Plaintiffs Name or Likeness in AdvertisingDocument89 paginiInvasion of Privacy by Use of Plaintiffs Name or Likeness in AdvertisingAustin100% (1)

- Service Manual: Component Hi-Fi Stereo SystemDocument96 paginiService Manual: Component Hi-Fi Stereo SystemGeronimo Geronimo AÎncă nu există evaluări

- GNURadio Tutorials ReportDocument2 paginiGNURadio Tutorials Reportvignesh126Încă nu există evaluări

- ShawDocument12 paginiShawMihaela DrimbareanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Golu Hadawatha Novel PDFDocument3 paginiGolu Hadawatha Novel PDFDiane0% (1)

- Kalaingar Magalir Urimai Thittam (ITK - EV) Details 12.07.23Document36 paginiKalaingar Magalir Urimai Thittam (ITK - EV) Details 12.07.23Jeyakumar ArumugamÎncă nu există evaluări

- RL Circuits - Electrical Engineering Questions and Answers Discussion Page For q.521Document2 paginiRL Circuits - Electrical Engineering Questions and Answers Discussion Page For q.521AmirSaeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multi Pulse Width Modulation Techniques (MPWM) : Experiment AimDocument4 paginiMulti Pulse Width Modulation Techniques (MPWM) : Experiment AimAjay Ullal0% (1)

- PTR MOSES CARLOS B. AGAWA - RESUME / CV - Updated December 2010Document12 paginiPTR MOSES CARLOS B. AGAWA - RESUME / CV - Updated December 2010Ptr MosesÎncă nu există evaluări

- OEMV® Family: Installation and Operation User ManualDocument182 paginiOEMV® Family: Installation and Operation User ManualBejan OvidiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- DRF1301 1000V 15A 30MHz MOSFET Push-Pull Hybrid DriverDocument4 paginiDRF1301 1000V 15A 30MHz MOSFET Push-Pull Hybrid DriverAddy JayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electrical Design Criteria - Rev.2Document13 paginiElectrical Design Criteria - Rev.2civilISMAEELÎncă nu există evaluări

- Verb Tenses ExercisesDocument10 paginiVerb Tenses ExercisesIsabela PugaÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Radio StationsDocument13 paginiList of Radio StationsNishi Kant ThakurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Improvisation and Sketch Comedy PDFDocument19 paginiImprovisation and Sketch Comedy PDFLiam LagwedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Field Test ModesDocument2 paginiField Test ModesDiego ZagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Search IndexDocument23 paginiSearch IndexMaria SpitzerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oliveros Sonic Meditation 0002 Pauline Oliveros PDFDocument6 paginiOliveros Sonic Meditation 0002 Pauline Oliveros PDFfrancisco osorio adameÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arab Iqa'atDocument5 paginiArab Iqa'atrenewedÎncă nu există evaluări

- RTE National Symphony Orchestra 2018-2019 SeasonDocument80 paginiRTE National Symphony Orchestra 2018-2019 SeasonThe Journal of MusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- VHF Vehicle Roof-Top Antennas: Installation ManualDocument16 paginiVHF Vehicle Roof-Top Antennas: Installation ManualLuis MantillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kenwood Dpx304 Dpx308u Dpx404u Dpx-mp3120 Dpx-U5120 Dpx-U5120sDocument58 paginiKenwood Dpx304 Dpx308u Dpx404u Dpx-mp3120 Dpx-U5120 Dpx-U5120sLeonel MartinezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1ME1000slides03bMicrowaveFiltersv2 70Document91 pagini1ME1000slides03bMicrowaveFiltersv2 70हिमाँशु पालÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPAR Reviewer Guide for GAMABA AwardeesDocument3 paginiCPAR Reviewer Guide for GAMABA AwardeesZennia PorcilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gallay 14 Horn Duets PDFDocument13 paginiGallay 14 Horn Duets PDFFrancisco Herrera100% (2)

- AW-NB037H-SPEC - Pegatron Lucid V1.3 - BT3.0+HS Control Pin Separated - PIN5 - Pin20Document8 paginiAW-NB037H-SPEC - Pegatron Lucid V1.3 - BT3.0+HS Control Pin Separated - PIN5 - Pin20eldi_yeÎncă nu există evaluări