Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Claimant Memorandum, National Law University-Vis Vienna, 2014

Încărcat de

Aayush SrivastavaDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Claimant Memorandum, National Law University-Vis Vienna, 2014

Încărcat de

Aayush SrivastavaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

XXI Annual Willem C.

Vis International Commercial Arbitration Moot

In the matter of Arbitration under The Belgian Center for Arbitration and Mediation Rules, 2013 CEPANI No. 22780: Innovative Cancer Treatment Ltd. v. Hope Hospital

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

ON BEHALF OF: CLAIMANT Innovative Cancer Treatment Ltd. 46 Commerce Road Capital City, Mediterraneo Tel- (0) 4856201 Telefax- (0) 4856201 01 E-mail- info@ict.me AGAINST: RESPONDENT Hope Hospital 1-3, Hospital Road Oceanside, Equatoriana Tel- (0) 238 8700 Telefax- (0) 238 87 01 E-mail- office@hospital.eq

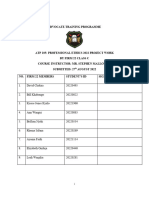

COUNSELS

AAYUSH SRIVASTAVA

AKSHAY SHREEDHAR

BALVINDER SANGWAN

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS..............................................................................................V BRIEF OVERVIEW OF KEY FACTS.................................................................................1 INTRODUCTORY REMARKS ABOUT ARGUMENTS ADVANCED...........................2 ARGUMENTS ON THE JURISDICTION OF THE TRIBUNAL...................................3 I. THERE EXISTS A VALID ARBITRATION AGREEMENT UNDER THE FSA............................................................................................................................3 A. THE ARBITRATION AGREEMENT IS VALID AS IT LEADS TO A BINDING AWARD DUE TO

SUBMISSION TO CEPANI RULES.............................................................................4

1. Submission to CEPANI rules waives any right to recourse against an arbitral award...4 2. CEPANI rules override the clause on appeals and review mechanism under Art. 23(4) of the FSA...............................................................................................................................5 3. In case of uncertainty in determining intention, the arbitration agreement should be salvaged by severing the appeals and review mechanism..................................................6 a. The tribunal must salvage the arbitration agreement in light of conflicting intentions.................6 b. Severing the appeals and review mechanism does not nullify RESPONDENTs intention to arbitrate................................................................................................................................6 B. IN ANY EVENT, RESPONDENT SHOULD NOT BE ALLOWED TO BENEFIT FROM ITS

OWN INACTION.......................................................................................................7

1. RESPONDENT may not seek the excuse of mistake of law and receive undeserved benefit......................................................................................................................................7 2. The application of the principle of contra proferentem, if at all, results in an interpretation against RESPONDENT............................................................................................................8 C. IN

THE ALTERNATIVE, EXTRA-ORDINARY RECOURSE UNDER

ART. 23(4)

OF THE

FSA DOES NOT LEAD TO A NON-BINDING AWARD UNDER ANY LAWS POTENTIALLY

APPLICABLE TO THE ARBITRATION AGREEMENT ...................................................9

1. Appeals and review mechanism in Art. 23(4) of the FSA is valid under EAL.....................................................................9

Page | i

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

a. Tribunal must apply EAL as the law governing the arbitration agreement as per the validation principle.............................................................................................................................10 b. Art. 23(4) of the FSA falls within the scope of Article 34A of EAL..........10 2. In the alternative, the appeals and review mechanism is valid under the Danubian and/or the Mediterranean Law..........................................................................................11 a. The appeals and review mechanism is consistent with residual discretion exercised by courts in cases of manifest error..........................................................................................................12 b. Alternatively, the principles of party autonomy should be favored over finality and heightened judicial review should be allowed............................................................................................13 c. In the alternative, invalidating Art. 23(4) of the FSA will result in application of arbitration agreement under Sec. 21 of the November 200 T&Cs..........................................................13 D. THE GRANT OF THE UNILATERAL OPTION TO THE SELLER DOES NOT INVALIDATE

THE ARBITRATION AGREEMENT............................................................................14

1. The unilateral option does not violate the principles of mutuality................................14 2. The option ceases to exist at its exercise by CLAIMANT..................................................15 II. CLAIMS UNDER THE SLA CAN BE ARBITRATED UNDER THE DISPUTE RESOLUTION CLAUSE OF THE FSA.................................................................15 A. ART. 23 OF THE SLA IS NOT CONTRARY TO ART. 23 OF THE FSA. ...........................15 B. THE III. THE

INTENTION TO ARBITRATE IS NOT NULLIFIED BY AN OPTION TO LITIGATE..............................16

ARBITRAL

TRIBUNAL TO HEAR

HAS BOTH

THE

COMPETENCE IN A

AND

JURISDICTION

CLAIMS

SINGLE

ARBITRATION....................................................................16 A. THE TRIBUNAL HAS THE JURISDICTION AND THE COMPETENCE TO DECIDE THE

CLAIMS IN A SINGLE ARBITRATION........................................................................17

1. The FSA and the SLA are part of a unified contractual scheme...............................17 2. The claims are economically connected and indivisible..................................................17 B. THE TRIBUNAL SHOULD DECIDE THE CLAIMS IN A SINGLE ARBITRATION..............18 1. Single set of proceedings prevents conflicting awards.......................................................18 2. An arbitrator of different expertise may not be needed.....................................................19 Page | ii

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

3. Single set of proceedings leads to greater efficiency..................................................20 ARGUMENTS ON DETERMINATION OF APPLICABLE LAW.................................20 IV. THE SLA LIES WITHIN THE SPHERE OF APPLICABILITY OF THE CISG.....................................................................................................................20 A. ELECTRONICALLY TRANSMITTED

SOFTWARE QUALIFIES AS GOODS WITHIN THE CISG.......................................................................................................................21

1. Software under the SLA qualifies as goods irrespective of intangibilty....................21 2. The tribunal must apply the CISG to electronically transmitted software.................................................................................................................................22 B. ART. 2 OF THE SLA CONSTITUTES A VALID SALE OF THE SOFTWARE...23 1. The software licence is a valid sale in the sense of the CISG........................................23 2. CLAIMANT is not under any obligation to transfer intellectual property under a sale.......................................................................................................................................24 C. ART. 3 OF THE CISG DOES NOT EXCLUDE THE SLA.............................................24 1. The fact that software has been customized remains inconsequential.......................25 2. RESPONDENTs contribution is not substantial...............................................................25 3. Value of the labour and other services provided under the SLA does not amount to a preponderant part...........................................................................................................26 V. THE JULY 2011 STANDARD TERMS HAVE BEEN 2011 VALIDLY INCORPORATED INTO THE SLA......................................................................27 A. CLAIMANT

MADE ITS INTENTION TO BE BOUND BY JULY STANDARD TERMS CLEAR, THEREBY, CONSTITUTING VALID OFFER...................................................28

1. The offer was definite and showed intention to be bound...........................................28 2. Standard terms were validly made available to RESPONDENT.....................................29 B. RESPONDENT

WAS CONSTRUCTIVELY AWARE OF THE CONTENT OF THE NEW STANDARD TERMS AND THEREFORE VALIDLY ACCEPTED THEM..........................29

1. RESPONDENT had a reasonable opportunity to be aware of the content of the T&Cs.30 2. Conduct of RESPONDENT created an impression that it understood the T&Cs.....................................................................................................................................31 C. DR. VIS

STATEMENTS ABOUT CHANGES MADE IN

T&CS

ARE IRRELEVANT FOR

THEIR VALID INCORPORATION..............................................................................32

Page | iii

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI VI.

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

SEC. 22 OF THE JULY 2011 T&CS LEADS TO THE APPLICATION OF THE CISG..33 A. A B.

REFERENCE TO THE LAW OF

MEDITERRANEO

MUST BE CONSTRUED AS A

REFERENCE TO THE CISG......................................................................................33 THE CHOICE OF LAW CLAUSE CANNOT BE UNDERSTOOD AS AN EXCLUSION OF THE CISG......................................................................................................................33

REQUEST FOR RELIEF..35 INDEX OF SCHOLARLY WRITINGSVIII INDEX OF COURT CASES.....XXII INDEX OF ARBITRAL AWARDS..XXXI INDEX OF LEGAL ACTS AND RULES.XXXIII INDEX OF OTHER SOURCES..............XXXIV CERTIFICATE.........XXXVI

Page | iv

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

& / Ans. to RFA Arb. Art. /Arts. BGH And Section Paragraph/Paragraphs Answer to Request for Arbitration Arbitration Article/Articles Bundesgerichtshof (Federal Supreme Court of Germany) CD-ROM CE CEPANI Compact Disc Read Only Memory CLAIMANTs Exhibit Arbitration Rules of the Belgian Centre for Arbitration and Mediation, 2013 Cir. CISG Circuit United Nations Convention on Contracts For Sale of Goods, 1980 Cl. Ex. CLOUT Comm. DAL Claimants Exhibit Case Law on UNCITRAL Texts Commentary Danubia Law on International Commercial Arbitration Dr. e.g. ed. / eds. Et al Doctor Exampli Gratia; for example Editor/ Editors Et Alii/ Alia, and others Page | v

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI Etc. fn. FSA

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT Et Cetera/ and so on Footnote Framework and Sales Agreement (CLAIMANTs Exhibit No. 2)

HCC HG

Hungarian Chamber of Commerce Handelsgericht Switzerland) (Commercial Court,

IBA ICT/CLAIMANT LG No./ Nos. NY Convention

International Bar Association Innovative Cancer Treatment Ltd. Landgericht (District Court, Germany) Number/ Numbers The Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, New York, 10 June 1958

NZ OGH

New Zealand Oberster Austria) Gerichtshof (Supreme Court of

OLG

Oberlandesgericht (Higher Regional Court in Germany)

p. / pp. Proc. Ord. No. 1 Proc. Ord. No. 2 Prof. q./ qq. r/w Re. Ex.

Page/ Pages Procedural Order No 1 Procedural Order No 2 Professor Question/ Questions Read with RESPONDENTs Exhibit Page | vi

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI RFA RESPONDENT SLA

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT Request For Arbitration Hope Hospital Sales and Licensing Agreement (CLAIMANTs Exhibit No. 6)

T&Cs ToR U.C.C. UK

Standard Terms and Conditions For Sale Terms of Reference Uniform Commercial Code The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

UNCITRAL

United Nations Commission on International Trade Law

UNIDROIT

International Institute for the Unification of Private Law Principles of International Commercial Contracts

USA USD v./ vs. Vol. ZCC

The United States of America United States Dollar Versus Volume Zurich Chamber of Commerce

Page | vii

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

BRIEF OVERVIEW OF FACTS

1. Both the claims in this arbitration arise out of non-payment of dues under two contracts; the Framework and Sales Agreement (FSA) and the Sales and Licensing Agreement (SLA). This arbitral hearing is restricted to determining the validity of the arbitration agreement, the jurisdiction of the tribunal to hear the aforementioned claims in a single set of proceedings and the applicable law to merits of the dispute. 2. The FSA was entered into between Innovative Cancer Treatment Ltd. (CLAIMANT) and Hope Hospital (RESPONDENT) on 13th January, 2008. The FSA was entered for the supply of a Proton Therapy Facility in Hope Hospital (see figure below) which was to be used for the treatment of cancer using passive beam scattering technique. The price of the facility was USD 50 million, to be paid in six installments. RESPONDENT was eager to purchase the active scanning technology, but was not able to do so for several reasons. Three years later, in 2011, RESPONDENT renewed interest in purchasing the same.

3. The price of the active scanning technology was still an issue, but finally a price of USD 3.5 million was agreed upon. The SLA was concluded on 20th July, 2011 under the framework of the FSA. The FSA was annexed with the Standard Terms and Conditions (T&Cs) of CLAIMANT, which were subsequently amended for the SLA. On 15th August, 2012, RESPONDENT sent a letter to CLAIMANT notifying that it would not be paying the remaining USD 10 million under the FSA and the USD 1.5 million, under the SLA. CLAIMANT subsequently invoked Art. 23 to submit both the claims to arbitration under CEPANI Rules of Arbitration, 2013 (CEPANI Rules) to be conducted in Vindobona, Danubia.

Page | 1

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS ABOUT ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

4. Ex turpi causa non oritur actio (No man can benefit from his own wrong/inaction). RESPONDENT has sought to take advantage of its own undoing. This attitude is reflected in all the positions taken by it to strategically delay payment of dues. For instance, Art. 23(3) of the FSA reflects an unequivocal intention to arbitrate. However, RESPONDENT seeks to nullify it by invalidating a non-related term provided by its own self [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 10; Ans. to RFA, 5]. The tribunal consequently needs to determine the validity of this arbitration agreement [ISSUE I.]. 5. Art. 45 of the FSA states that the FSA governs all future contracts. RESPONDENT was offered an option to litigate under the SLA, to recognize its contribution [Cl. Ex. No. 3]. Now it seeks to use this to prevent application of the arbitration agreement to claims under the SLA. CLAIMANT will demonstrate that an additional option to litigate in the SLA does not replace the arbitration agreement applicable to the SLA [ISSUE II.]. 6. The technology supplied under the SLA is an extension of the existing facility [Re. Ex. No. 2]. Goods supplied under FSA were essential for the working of the goods supplied under the SLA [Ans. to RFA, 23]. RESPONDENT now asserts that both claims must be decided separately [Ans. to RFA, 12]. The tribunal must decide on its jurisdiction to hear disputes arising out of the SLA and the FSA in a single proceeding [ISSUE III.]. 7. The law governing the SLA is disputed. The active scanning technology involves supply of equipment and a specialised software, which RESPONDENT terms as intangible [Ans. to RFA, 19]. CLAIMANT will demonstrate that the SLA fulfils the basic requirements of applicability of the CISG [ISSUE IV.]. 8. The T&Cs of July, 2011 provide the choice of law as law of Mediterraneo for the SLA [Sec. 22, 2011 T&Cs, Cl. Ex. No. 9]. RESPONDENT failed to verify these new terms and now claims that they were not validly incorporated in the SLA. CLAIMANT will demonstrate that the July 2011 T&Cs are applicable to the SLA [ISSUE V.]. The effect of such incorporation results in the application of the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG) as the law governing merits [ISSUE VI.]. Arguments on the merits of the claim and quantum of damages have been deferred to a separate hearing [Proc. Ord. No. 1, 3(1); Proc. Ord. No. 2, 1].

Page | 2

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

ARGUMENTS ON THE JURISDICTION OF THE TRIBUNAL

9. The Tribunal has the power to decide on its jurisdiction pursuant to the principle of kompetenzkompetenz [Blackaby et al, p. 347]. Therefore, the tribunal may rule on the validity of the arbitration agreement, a question submitted to it in the Terms of Reference [ToR, 5]. 10. In order to show that the tribunal has jurisdiction over these claims, CLAIMANT will demonstrate that there exists a valid arbitration agreement covering disputes arising out of the FSA [I.] as well as the SLA [II.]. Further, the tribunal has the jurisdiction and competence to hear both the claims together in a single proceeding [III.]. I. THERE EXISTS A VALID ARBITRATION AGREEMENT UNDER THE FSA 11. The arbitration agreement is contained in Art. 23 of the FSA. RESPONDENT challenges the validity of the arbitration agreement by alleging that it leads to a non-binding award, and is therefore uncharacteristic of an arbitration [Ans. to RFA, 7]. However, RESPONDENT confuses the distinction between the requirement of finality and that of a binding award. 12. The words final and binding have not been defined anywhere, either in the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration, adopted with 2006 amendments (MAL) or New York Convention on Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Awards, 1958 (NY Convention). The MAL and NY Convention however, refer to a binding award, respectively, under Art. 36 and Art. V, which are pari materia to each other. The standard to refuse enforcement under both, reads as follows: Recognition and enforcement of the award may be refused...the award has not become binding on the parties. 13. The NY Convention dropped the finality requirement for an award to be binding which existed under the Geneva Convention. Under the Geneva Convention, confirmation of the award was required at the seat of arbitration before enforcement (the double exequator requirement) [Travaux Preparatoires, NY Convention; Van den Berg, p. 338; Karaha Bodas, 2003 (USA)]. Consequently, courts have held awards to be binding despite the possibility of future judicial action [infra, 56]. 14. When there is a provision for an extra-ordinary recourse against an award, such as appeals on merits, the same may lead to a non-binding award [Gaillard/Savage, 974; GMTC, 1979 (Sweden); SPP v Egypt, 1984 (ICSID); BGH, 14.04.1988 (Germany)]. However, courts and scholars now disagree with the approach of changing the nature of the award based on the type of recourse provided. They suggest deference to the principles of party autonomy, and the rendering of the award as binding even during the pendency of extra-ordinary recourse [Inter-Arab Inv., 1997

Page | 3

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

(Belgium); Spanish TS, 20.07.2004 (Spain); Zhejiang Province, 1992 (Hong Kong); Ukrvneshprom, 1996 (USA)]. 15. Art. 23(4) of the FSA contains an appeals and review mechanism which allows recourse against an award, if it is obviously wrong in law or fact. This is an instance of extra-ordinary recourse, i.e. not provided under Art. 34 of the MAL. At the same time, parties have submitted to CEPANI rules which do not allow extra-ordinary recourse against an award [Art. 32, CEPANI Rules]. 16. There are two possible inferences of the law possible- either extra-ordinary recourse leads to a non-binding award or extra-ordinary recourse does not lead to a non-binding award under principles of party autonomy. CLAIMANT will demonstrate that under each interpretation of the law, the arbitration agreement is valid. Firstly, submission to CEPANI rules leads to exclusion of extra-ordinary review, and such submission to CEPANI rules overrides the appeals and review mechanism in Art. 23(4) of the FSA [A.]. In any event, RESPONDENT should not be allowed to benefit from its own inaction [B.]. In the alternative, extra-ordinary recourse does not lead to a non-binding award under the arbitration law of any country involved [C.]. Finally, the unilateral option clause is not one-sided and does not affect the validity of the arbitration agreement [D.]. A. THE ARBITRATION AGREEMENT IS VALID AS IT LEADS TO A BINDING AWARD DUE

TO SUBMISSION TO CEPANI RULES

17. The parties agreed to submit their disputes to arbitration under CEPANI Rules, which results in a final and binding award. Submission to CEPANI Rules automatically results in exclusion of extra-ordinary recourse, such as one contained in Art. 23(4) of the FSA [1.]. It may seem therefore, that there exist two contrary provisions in the FSA: Arts. 23(4) and 23(3). However, submission to CEPANI Rules overrides the clauses on appeals and review mechanism under Art. 23(4), as reflected from the intention of the parties [2.]. In case of uncertainty in determining intention, the arbitration agreement should be salvaged, by severing the appeals and review mechanism [3.].

1. Submission to CEPANI rules waives any right to recourse against an arbitral award

18. Art. 32(2) of the CEPANI Rules bars any recourse against an arbitral award, so far as such waiver can be validly made under the applicable law. Art. 32(2) however, states that this waiver is valid unless an express waiver is required under the applicable law. The applicable law in the present case, the MAL is silent on the validity of waiver of recourse against an award on the grounds in its Art. 34 [Born, p. 2867]. Page | 4

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

19. While certain Model Law countries like Canada allow waiver of recourse under Art. 34, others like New Zealand do not [Noble China, 1998 (Canada); Methanex Motonui, 2004 (NZ)]. In either case, waiver of recourse over and above Art. 34 of the MAL can be validly made. Art. 23(4) of the FSA is not covered in the grounds provided under Art. 34. So, even if the legal position does not allow waiver of grounds under Art. 34, the parties have definitely agreed to waive any recourse over and above that. 20. Such implied waiver has been considered to be valid when institutional rules provide for such exclusion, such as Art. 26(9) of LCIA Rules, Art. 28(9) of SIAC Rules and Art. 34(6) of ICC Rules. While Art. 34(2) of UNICTRAL Rules also provides for any award to be final and binding, the ICC and CEPANI rules go further and require waiver of any recourse. 21. Recently, Singapore High Court held a reference to the ICC Rules in the arbitration clause, sufficient to exclude the right of the parties [Daimler South East Asia, 2012 (Singapore)]. Similarly, Lord Steyn in the House of Lords stated, The parties are free to exclude this right of appeal by agreement. They did so by ICC Rules, Art. 28.6 in the case before the House [Lesotho Highlands, 2005 (UK)].

2. CEPANI Rules override the clause on appeals and review mechanism under Art. 23(4) of the FSA

22. Art. 23(4) of the FSA begins with the words The arbitral award shall be final and binding upon the parties. This confirms that parties intended that effect should be given to Art. 32 of the CEPANI Rules. Gary B. Born suggests that in order to determine if an award is binding, deference should be made to the parties agreement [Born, p. 2825]. Art. 23(3) also uses the terms such disputeshall be finally settled under the CEPANI rules... All of the above reflects the intention of the parties for the award to be binding. 23. The intention of the parties to give preference to CEPANI Rules over the appeals and review mechanism is evident from the italicization of the Rules, in Art. 23(3) of the FSA which adds emphasis to it. The clause reads, such disputes shall become subject to arbitration, to be finally settled under CEPANI Rules of Arbitration before CEPANI- The Belgian Centre for Arbitration and Mediation at Rue des Sols/Stuiverstraat Nr. 8, 1000 Brussels.... This is not merely a way of writing the full name of the institution, but an intentional adding of emphasis [Gallaway Cook, 2013 (NZ); Kenneth Adams, p. 197]. Adding of emphasis is further evidenced from lack of italicization when the CEPANI Rules were referred to in both the T&Cs [Sec. 21, Annex 4, FSA; Cl. Ex. No. 9].

Page | 5

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

24. Even if exclusion of recourse was an implied term, RESPONDENT cannot make a claim that it did not apply its mind to such implicit reference. When such a similar position was taken by a party, in a case where submission to ICC rules led to exclusion of right to appeal, the Singapore High Court held, that parties are bound by the terms of their contract, regardless of whether they had addressed their minds specifically to each and every term [Daimler South East Asia, 2012 (Singapore)]. RESPONDENT cannot benefit from its own inaction.

3. In case of uncertainty in determining intention, the arbitration agreement should be salvaged by severing the appeals and review mechanism

25. At best, the tribunal can hold that the intention is uncertain and in such a situation it must salvage the arbitration agreement by severing the appeals and review mechanism [a.]. The only other alternative is to sever the submission to CEPANI rules, which is more central to intention to arbitrate, than the appeals and review mechanism [b.]. a. The tribunal must salvage the arbitration agreement in light of conflicting intentions

26. An arbitration agreement with an appeals and review mechanism, can in some cases amount to a pathological clause [Gaillard/Savage, p. 263]. Parties often enter into such clauses due to ignorance of law [Born, p. 675]. In most cases, the arbitrators or the courts salvage the arbitration clause by restoring the true intention of the parties, which was distorted by the parties being unaware of the mechanics of arbitration [Lew/Mistelis/Krll, pp. 156-7; Gaillard/Savage, p. 264]. A similar situation has taken place in the present case as the dispute resolution clause was included by lawyers who were not aware of the intricacies of arbitration [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 10]. 27. An interpretation by the tribunal that the intention to arbitrate is contingent on the existence of the appeals and review mechanism, renders the arbitration agreement ineffective. CLAIMANT urges the tribunal to adopt the alternative interpretation and salvage the arbitration agreement, in line with the principle of in favorem validitatis [Poudret/Besson, 300; Mantilla-Serrano, p. 371]. b. Severing the appeals and review mechanism does not nullify RESPONDENTs intention to arbitrate 28. RESPONDENT argues that it would not have agreed to arbitration in the absence of the appeals and review mechanism [Ans. to RFA, 8]. However, Art. 23(4) of the FSA which contains the appeals and review mechanism, begins with the wording that the award shall be final and binding. RESPONDENT relies on what is commonly known as the but for test, which has been rejected by courts [Gallaway Cook, 2013 (NZ); Swiss FT, 22.03.2007 (Switzerland)]. Courts have Page | 6

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

also held that the presence or lack of an appeals and review mechanism is not central to the intention to arbitrate [Kyocera, 2002 (USA); Auto Stiegler, 2003 (USA); Carney, 1985 (UK)]. 29. Intention with regard to the importance of a provision has to be determined a priori, especially in the absence of a clause on severability or precedence [Born, p. 1208]. RESPONDENT has asserted that it is imperative to its intention to arbitrate to have an appeals and review mechanism [Ans. to RFA, 8]. However, the Circular No. 265 is not binding on RESPONDENT as it is not a government entity, and moreover they are mere guidelines [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 9]. RESPONDENT had deviated from the Circular in the past and agreed to arbitration without an appeals and review mechanism [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 9]. 30. In that case, there was considerable public discussion about the deviation and RESPONDENT wanted to avoid it in the present case [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 9]. However, none of the above was conveyed to CLAIMANT at the time of signing the FSA [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 9]. Therefore, the appeals and review mechanism was included as a matter of convenience and had it been central to the intention to arbitrate, all the RESPONDENTs reasons would have been disclosed a priori. B. IN ANY EVENT, RESPONDENT SHOULD NOT BE ALLOWED TO BENEFIT FROM ITS

OWN INACTION

31. Art. 1.8 of the UNIDROIT Principles states that, A party cannot act inconsistently with an understanding it has caused the other party to have, and upon which that other party acted in reliance to its detriment. The concept of estoppel states that a party is precluded from acting contrary to its former conduct if the other party relied on that conduct [Blackaby et al, 4.76; Art. 4, MAL]. 32. RESPONDENT claims that the appeals and review mechanism is invalid despite it being the party which demanded that particular provision. RESPONDENT cannot seek the benefit of mistake of law to avoid the arbitration agreement, as it didnt exercise reasonable care and caution [Born (2013), p. 111]. CLAIMANT contends that RESPONDENT may not claim common mistake of law and seek an undeserved benefit [1]. Further, the application of the principle of contra proferentum results in an interpretation against RESPONDENT [2].

1. RESPONDENT may not seek the excuse of mistake of law and receive undeserved benefit

33. RESPONDENT is likely to claim that it was unaware of the existing law, and therefore it was a common mistake of law. However, as per UNIDROIT Principles, to avoid obligations under mistake of law, the same must not be an error of judgment [Official Comments to Art. 3.2.2, UNIDROIT Comm]. RESPONDENT asserts more than five years after the signing of the FSA, that it realised that the appeals and review mechanism is void [Ans. To RFA, 6]. Now Page | 7

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

RESPONDENT seeks to take advantage of its error of judgment regarding the appeals and review mechanism and avoid its application under a voluntary agreement. 34. In determining whether an invalid provision may be severed, the tribunal must look to the overall interests of justice and must not allow a party to gain an undeserved benefit [Mayer, p. 261; Peter Hay et al, p. 4; Auto Stiegler, 2003 (USA); Gallaway Cook, 2013 (NZ)]. In the Kyocera case, the court dealt with a similar question and held, one of the parties would gain an undeserved benefit if we were to find the whole of the parties arbitration agreement invalid [due to an invalid expanded review clause] when the arbitration itself suffered from no infirmity [Kyocera, 2002 (USA)]. 35. RESPONDENT gains an undeserved benefit of delaying recovery of amount due to CLAIMANT, by invalidating the arbitration agreement. This is a delay tactic which acutely affects the interests of CLAIMANT when it has performed its part of the contract. Further, there is no harm to the RESPONDENT if the clause is severed as it is not certain whether the award will be against it.

2. The application of the principle of contra proferentem, if at all, results in an interpretation against RESPONDENT

36. RESPONDENT is likely to contend that because CLAIMANT drafted the dispute resolution clause, the application of the contra proferentem rule allows the sentence to be interpreted favourably towards RESPONDENT. In fact, RESPONDENT incorrectly made a factual assertion that the appeals and review mechanism discussed on 4th November, 2007 was later amended by CLAIMANT [Ans. to RFA, 6]. The Proc. Ord. No. 2 in 10 clarifies this, by stating that, the clause [as agreed by the parties] was included verbatim into the draft prepared by the CLAIMANT. 37. The principle of contra proferentem should not be applied to this situation. Even though the dispute resolution clause was drafted by CLAIMANTs lawyers, it was reviewed by the lawyers of RESPONDENT [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 10]. It was therefore, jointly drafted and hence, does not allow for the application of the contra proferentem rule [Bonell, p. 242; Lewison, p. 209]. The principle of contra proferentem is only applicable if the drafting party was entirely responsible for the clause in question [Haraszti, p. 191; Berglin, p. 69; ICC Case 4727/1987; Techniques l'Ingenieur, 1980 (France)]. 38. If the tribunal finds the contra proferentem in principle applicable, it would in fact benefit CLAIMANT. The principle of contra proferentem is directed towards the initiator of the disputed terms rather than the drafter [Gelot, p. 270]. The English version of the rule, as adopted in UNIDROIT principles uses the word supplier [Art. 4.6, UNIDROIT]. However, this is inconsistent with other linguistic interpretations. The French (proposer), Spanish (dictar), Page | 8

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

Italian (stabilire) and German (verwenden) versions are interpreted as the party who proposes the particular terms instead of the drafter as the initiator benefiting from the clause [Gelot, p. 264-273; McMeel, p. 190]. 39. RESPONDENT had cited the circular of Auditor General to insert the appeals and review mechanism [Re. Ex. No. 2]. However, CLAIMANT was never made aware of the exact wording of the Circular of Auditor General or background due to which RESPONDENT insisted on the appeals and review mechanism [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 9]. Given RESPONDENTS inaction in this respect, the clause should be read in favor of CLAIMANT, i.e. the appeals and review mechanism should be interpreted as not being integral to the intention to arbitrate. C. IN

THE ALTERNATIVE, EXTRA-ORDINARY RECOURSE UNDER

ART. 23(4)

OF THE

FSA DOES NOT LEAD TO A NON-BINDING AWARD UNDER ANY LAWS POTENTIALLY

APPLICABLE TO THE ARBITRATION

AGREEMENT

40. The laws that are potentially applicable to the present arbitration agreement are the International Commercial Arbitration laws of Mediterraneo, Danubia or Equatoriana. All these three countries have adopted the MAL [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 13]. 41. While the arbitration laws of Mediterraneo and Danubia are verbatim adoptions of the MAL, in Equatoriana the MAL has been adopted with two closely related amendments [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 13]. Firstly, the scope of application of the law is not limited to international cases in the sense of Art. 1(3) of the MAL. Secondly, a provision codifying the framework for an appeal on merits has been included as Art. 34A [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 13]. CLAIMANT asserts, that notwithstanding the applicable law, appeals and review mechanism in Art. 23(4) of the FSA is valid under Equatoriana Law on International Commercial Arbitration (EAL) [1.]. In the alternative, it is valid under the DAL and/or the Mediterraneo Arbitration Law [2.].

1. Appeals and review mechanism in Art. 23(4) of the FSA is valid under EAL

42. In an international arbitration, parties have the freedom to choose the law applicable to their arbitration agreement [Born, p. 427; Art. V(1)(a), NY Convention]. This freedom is manifested either in an express choice of law, or in an implication drawn from the intention of the parties [Born, p. 410]. In the instant case, since the parties have not made an express designation of the choice of law, it becomes necessary to first determine which law will govern the validity of the arbitration agreement [Blackaby et al, p.165]. 43. Absent an explicit choice of law, a variety of national laws can potentially govern the validity of an arbitration agreement. These include the law which the parties have selected to govern the underlying agreement; the law of the arbitral seat; and the law of the country where an Page | 9

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

arbitral award would need to be enforced [Born (1996), p. 1011]. In the present case, the tribunal must apply EAL as the law governing the arbitration agreement as per the validation principle [a.] since, Art. 23(4) of the FSA falls within the scope of Article 34A of the EAL [b]. a. Tribunal must apply EAL as the law governing the arbitration agreement as per the validation principle 44. While determining the law governing the arbitration agreement, the most relevant criteria is the intention of the parties [Sulamrica, 2012 (UK)]. The primary reason behind the parties agreement to arbitrate is to obtain an efficient and neutral means of resolving their disputes [Curtin, p. 352]. As a natural corollary to this, parties cannot be presumed to intentionally select or to desire a law governing their arbitration agreement that might have the effect of invalidating one of the most important provisions of the contract [Born, p. 455]. Therefore, if there is more than one potential choice of law, the parties must be presumed to have intended to apply the law which would definitely uphold the validity of and enforce their agreement [Hook, p. 182; ICC Award 7154/1994]. 45. The validation principle has been recognised across jurisdictions [Art. 178, Swiss Law on Private International Law; Art. 9(6), Spanish Arbitration Act; Hook, p. 182, Born, p. 496; Westbrook Intl, 1995 (USA); Mergeb, 1994 (France); Sulamrica, 2012 (UK); ICC Award 7154/1994; ICC Award 6474/2000]. This principle reflects an in favorem validitatis approach, which demands the application of the law that ensures the protection of the validity and integrity of the parties agreement to arbitrate, as opposed to the law which might render the arbitration agreement invalid [ZCC, 25.11.1994; Pearson, p. 122]. 46. Further, the Hilmarton/Chromalloy jurisprudence, relying on the pro-arbitration bias under the NY Convention, allows parties to seek enforcement of awards where the losing party has assets, notwithstanding setting aside of award at the seat of arbitration [Gaillard/Edelstein, p. 37; Schwartz, p. 125; Hilmarton, 1997 (France); Chromalloy, 1996 (USA)]. Even if the award is set aside by courts of Danubia, Equatorianas courts will nevertheless have jurisdiction regarding the enforcement of the award. Therefore, it makes sense to apply EAL at this stage itself. b. Art. 23(4) of the FSA falls within the scope of Art. 34A of EAL 47. The appeals and review mechanism is valid under the EAL, because it falls within the scope of the autonomy envisaged under Art. 34A of EAL. However, even by providing for a right of appeal in cases of obvious errors of both law or fact, [Art. 23(4), FSA] the parties are in no way contracting beyond the aforementioned scope. This is because the only matters with respect to which an appeal is statutorily prohibited under Art. 34A(4) of EAL are matters of Page | 10

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

evidence and matters of secondary or inferential facts [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 13]. On the other hand, obvious errors of fact pertain to primary facts, which are not a result of reasoning, and appeals with respect to the same are not prohibited under Art. 34A(4) of EAL [Thayer, p. 194]. 48. The NZ Arbitration Act contains a provision similar to Art. 34A [Clause 5, Second Schedule, NZ Arbitration Act], and courts have severed the phrase or fact in a contract which allows for errors or law or fact as opposed to obvious errors of law or fact [Gallaway Cook, 2013 [NZ]. Therefore, the use of the word obvious distinguishes Art. 23(4) of the FSA from the exclusionary list provided under Art. 34A(4) of EAL.

2. In the alternative, the appeals and review mechanism is valid under the Danubian and/or the Mediterranean Law

49. The issue regarding validity of a clause expanding the scope of review has never been addressed in either Danubia or Mediterraneo [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 14]. Further, several MAL jurisdictions have diverging views on validity of such appeals and review mechanisms [Varady, pp. 253-276]. 50. Jurisdictions like UK, Belgium, China, Australia, Singapore, have considered it valid [S. 69, UK Arbitration Act; Art. 1703, Belgian Judicial Code; Born, p. 2639]. A contrary position has been taken in France, USA, Canada and Switzerland [Diseno, 1994 (France); Hall Street, 2008 (USA); Food Services of America, 1997 (Canada); Swiss FT, 08.04.2005 (Switzerland)] Even the IBA Guidelines for Drafting International Arbitration Clauses which are widely used while drafting arbitration agreements suggest a case by case approach. It states If the parties nonetheless wish to expand the scope of judicial review, specialized advice should be sought and the law at the place of arbitration should be reviewed carefully [IBA Guidelines, p. 29]. 51. In such a scenario, the tribunal must adopt a view which seeks to give effect to the arbitration agreement than the one which renders it ineffective. The appeals and review mechanism is consistent with residual discretion exercised by courts in cases of manifest error. This distinguishes the present case from most judicial authorities which disallow expansion of judicial review [a.]. Further, in the alternative, the principles of party autonomy should be favored over finality and heightened judicial review should be allowed [b.]. In the alternative, invalidating Art. 23(4) of the FSA will result in application of arbitration agreement under Sec. 21of the November 2000 T&Cs [c.]

Page | 11

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

a. The appeals and review mechanism is consistent with residual discretion exercised by courts in cases of manifest error 52. Art. 23(4) of the FSA which contains the appeals and review mechanism allows for appeals when the award is obviously wrong in law or fact. The use of the words obviously wrong distinguishes it from de novo review or fresh review by courts into the merits of the award. 53. The judicially created manifest disregard doctrine in USA provides for a similar standard of review [Born, pp. 2639-45; Hans Smit (Manifest Disregard); Stolt-Nielsen, 2010 (USA)]. It is also similar to the obviously wrong standard found in Sec. 69 of the Arbitration Act, 1996 of UK [Tweeddale/Tweeddale, 808; The NEMA, 1982 (UK); Lesotho Highlands, 2005 (UK);]. Furthermore, in Australia obviously wrong errors fall within the manifest error standard of review [Westport Insurance, 2010 (Australia); Natoli, 1994 (Australia)]. 54. An award marred by egregious/manifest errors or those which are wrong on the face of it are often set aside under Art. 34(5) of MAL and Art. V(2)(b) of NY Convention [Schmitthoff, p. 230; Hans Smit (Manifest Disregard)]. Arbitral tribunals tend to make manifest errors when interpreting or applying the statutory or judicial authority. Such scenarios, therefore justify the setting aside of the award on the basis of public policy [Born, p. 2564; Baxter, 2003 (USA)]. 55. Further, several jurisdictions have classified awards as binding even if there exists the possibility of future judicial action at the seat of the arbitration [Fertilizer Corp., 1981 (USA); Inter-Arab Inv., 1997 (Belgium); Swiss FT, 26.08.1982 (Switzerland)]. This has been done to remove the double exequator requirement, so that the pendency of recourse at seat does not render the award non-binding [Inter Maritime Mgt., 1995 (Switzerland); Socit Nationale D'oprations, 2001 (Hong Kong); OLG Bavaria, 22.11.2002 (Germany); Compare Dworkin-Cosell, 1989 (USA)]. 56. Even jurisdictions which do not allow for appeals on merits, permit them on grounds similar to the obviously wrong standard albeit under different terminologies [Born, pp. 2638-47]. For example, German, French and Swiss courts have allowed for similar reviews under notions such as: of bonos moros [OLG Berlin, 27.05.2002 (Germany)], good faith [Norbert Beyrard, 1993 (France)], and public policy [Swiss FT, 10.11.2005 (Switzerland)]. 57. The tribunal must take a pragmatic view and note that any award which is obviously wrong in law or fact is likely to affront the very basis of the public policy of the state where the award is being reviewed or enforced. Courts in such situations will review the merits of the award on the limited grounds mentioned in any case, thus taking away any reason to not uphold the validity of the appeals and review mechanism.

Page | 12

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI b.

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

Alternatively, the principles of party autonomy should be favored over finality and heightened judicial review should be allowed

58. Arbitration is a creature of contract. The contractual origin of arbitration proceedings empowers parties to tailor the proceedings according to their wishes [Zekos, p. 4]. 59. The purpose behind a clause providing for an arbitral appeal is to eliminate the risk of an unprincipled or fundamentally erroneous decision [Hochman, p. 104; Fuchsberg, p. 2; Lord Dyson, p. 290]. Scholars argue that by providing for the statutory grounds for vacatur, legislatures could not have intended to block the parties freedom to agree upon other forms of judicial review [Born, p. 2669; van Ginkel, p. 188]. 60. Furthermore, the need for such a clause becomes more pronounced when the dispute arises out of an international transaction [Born, p. 2669; Sasser, p. 357]. This is because international cases presented to international arbitration tribunals are increasingly complex, both technically and financially, increasing the likelihood of error [Lew, p. 543]. In the case of a dispute where the stakes are so high, it is extremely risky to leave the parties with no effective means of review [Knull & Rubins, p. 542; AT&T Mobility, 2011 (USA)]. 61. As a result of it, some large-stake disputes are being litigated rather than arbitrated [Hayford/Peeples, p. 405]. In a survey of corporate lawyers from Americas corporations (606 participants), 54.3% of those who chose not to opt for arbitration stated that their choice was made predominantly because arbitration awards are difficult to appeal [Lipsky/Seeber]. Therefore, the policy considerations in favour of allowing parties to include such an appeal clause outweigh the considerations against the possibility of arbitral appeal, especially given the stakes involved in the present dispute [van Ginkel, p. 193]. c. In the alternative, invalidating Art. 23(4) of the FSA will result in application of arbitration agreement under Sec. 21of the November 2000 T&Cs 62. The FSA is governed by the November 2000 Standard T&Cs, by virtue of its Art. 46. Sec. 21 of T&Cs submits all disputes to arbitration, without any right of appeal [Sec. 21, Annex A, FSA]. RESPONDENT states that it did not agree to the dispute resolution mechanism during negotiations, and the parties agreed to replace it by Art. 23 of the FSA [Ans. to RFA, 10]. However, this replacement stands nullified if, as RESPONDENT suggests, Art. 23 is held to be invalid. RESPONDENT had manifested its intention to replace Sec. 21 by agreeing on a contrary provision, which no longer exists, thereby, revoking said intention [Art. 2.1.21, UNIDROIT]. 63. This brings Sec. 21 of the November 2000 T&Cs back to life. This clause does not suffer from any infirmities, as the ones alleged by RESPONDENT in case of Art. 23 of the FSA [Ans. to RFA, Page | 13

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

5-9]. The tribunal may then derive its jurisdiction from the arbitration agreement under Sec. 21 of the T&Cs, which provides Capital City, Mediterraneo as the place of arbitration. However, a tribunal may be present in a venue different from the seat of the arbitration [See generally: Scherer; Mann; Nakamura; Jarvin]. Therefore, the tribunal can remain seated in Vindobona, Danubia, and apply the law of the seat which is the law of Mediterraneo. D. THE GRANT OF THE UNILATERAL OPTION TO THE SELLER DOES NOT INVALIDATE

THE ARBITRATION AGREEMENT

64. Art. 23(6) of the FSA grants a right to CLAIMANT (Seller) to invoke litigation in case of nonpayment of dues by RESPONDENT. Consequently, in the limited case (like the present one) when RESPONDENT refuses to pay its due, CLAIMANT can chose between invoking arbitration and litigation. RESPONDENT alleges that this unilateral option to litigate granted to the seller is one-sided and therefore, renders the entire arbitration agreement invalid. Courts which rule against the validity of a unilateral option do so for two reasons- lack of mutuality [Money Place, 2002 (USA)] and lack of certainty of intention to arbitrate [Nesbitt/Quinlan]. To determine validity of such options, CLAIMANT will prove that the unilateral option does not violate the principles of mutuality [1.]. Further, the option ceases to exist at its exercise, and is therefore severable [2.].

1. The unilateral option does not violate the principles of mutuality

65. The principle of mutuality requires the existence of reciprocal rights [Hans Smit (2009)]. It is possible to locate the reciprocal rights granted to both parties under the arbitration agreement and underlying contract [Buckeye, 2006 (USA)]. The notion that the arbitration agreement is separate from the underlying contract was created to preserve its validity despite challenges to the underlying contract. Consequently, this approach has been rejected and one consideration in one part of the contract can support many considerations in the contract [Perillo, 4.15]. 66. In the case at hand, the unilateral option was secured by the seller by giving the buyer a substantial benefit. The FSA required a payment of USD 50 million, however, CLAIMANT on RESPONDENTs request allowed for the payment to be made in six instalments spread over six years [RFA r/w FSA]. In return, an option to litigate was voluntarily agreed upon [Cl. Ex. No. 3]. Such voluntarily granted options to litigate or arbitrate between parties are enforceable by giving due respect to party autonomy [Hans Smit (1997); Kaufman/Babbitt, p. 108; Court of Appeal, Angers, 25.09.1972 (France); Court Supreme di Cassazione, 22.10.1970 (Italy); Law Debenture, 2005 (UK); Willis Flooring, 1983 (USA)].

Page | 14

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

2. The option ceases to exist at its exercise by CLAIMANT

67. The option to litigate available with the CLAIMANT is not open-ended and would cease to be available if it took a step in the action or led the other party to believe on reasonable grounds that the option would not be exercised [NB Three Shipping (UK)]. Existence of an option to litigate is merely a choice. After any of the parties choses to arbitrate, such an option ceases to exist [OLG Stuttgart, 10.09.2009 (Germany); William Co, 1993 (Hong Kong); Messiniaki Bergen, 1993 (UK); Lobb Partnership, 2000 (UK)]. Only if none of the parties opt for arbitration, can a dispute be litigated in courts. 68. This introduces the element of certainty and does not risk long-winded proceedings which are later dismissed because of the exercise of an option. Even, if the tribunal were to hold the option in Art. 23(6) of the FSA to be invalid, it has the power to sever it from the agreement, given that its not integral to the intention to arbitrate. In this case, the CLAIMANT elected to follow arbitration proceedings, effectively rendering the option to litigate null and void. II. CLAIMS UNDER THE SLA CAN BE ARBITRATED UNDER THE DISPUTE RESOLUTION CLAUSE OF THE FSA 69. Both parties agreed to validly arbitrate disputes under the FSA, by virtue of Art. 23(3). Further, the parties also agreed that the provisions of the FSA, including the dispute resolution clause, shall govern all future contracts between the parties. However, there is an exception to this rule which states that provisions of the FSA shall not govern the SLA if it contains a specific provision to the contrary [Art. 45, FSA]. RESPONDENT claims that the Art. 23 of the SLA falls within the above exception, while CLAIMANT believes that its a mere modification. CLAIMANT will establish that Art. 23 of the SLA is not contrary to Art. 23 of the FSA [A.]. Further, an option to litigate for both parties does not nullify the intention to arbitrate [B.]. A. ART. 23 OF THE SLA IS NOT CONTRARY TO ART. 23 OF THE FSA 70. The word contrary is usually understood to mean opposite [Oxford Dictionary; Merriam-Webster]. To assess whether or not there exists a contradiction, the arbitral tribunal must establish the parties true intention [Gaillard/Savage, p. 270; Societe Glencore, 2000 (France)]. For a contradiction to arise, the provision contained in the SLA must be conflicting with the provision of the FSA and not merely different. CLAIMANT had offered to grant both the parties an additional option to also litigate any disputes without any intention to alter the intention to arbitrate [RFA, 21]. 71. Further, it is possible for both an option to arbitrate or litigate to co-exist in a contractual relationship. Such clauses are known as hybrid clauses. Courts have tried to reconcile such Page | 15

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

hybrid clauses and held that an arbitration agreement and an option to litigation are not inconsistent with each other [Law Debenture, 2005 (UK); Lee Chong, 2012 (Hong Kong); Internet East, 2001 (USA); Provincial Court, Madrid, 18.10.2013 (Spain)]. Moreover, the tribunal should try to provide meaning to both the clauses, and an inconsistency, if any, should be resolved by processes of construction [Yien Yieh, 1989 (Hong Kong); Lewison, 9.13; McMeel, 4.11-4.13]. 72. In Axa Re, High Court of England and Wales reconciled such clauses by holding that that the contract demonstrates that the parties do not treat arbitration and court as mutually exclusive. Instead, such clauses envisage arbitration as a step which may, or will, take place before any action in court [Axa Re, 2006 (UK)]. The designated court merely retains the supervisory jurisdiction [Paul Smith, 1991 (UK); Arta Properties, 1998 (Hong Kong); ICC Award 8179/2001] B. THE INTENTION TO ARBITRATE IS NOT NULLIFIED BY AN OPTION TO LITIGATE 73. The principles of effective interpretation are used to salvage the arbitration agreement, when jurisdiction can be referred to both courts and arbitration [ICC Award 6866/1992; ICC Award 5488/1993]. The intention to arbitrate is not nullified by having an option to litigate because of greater volitional intensity associated with arbitration agreements. 74. The theory of greater volitional intensity assumes that if the parties did not intend to submit their dispute to arbitration, they would have simply refrained from including an arbitration clause [Lee Chong, 2012 (Hong Kong); Cape Lambert, 2012 (Australia); Distribution Chardonnet, 1991 (France)]. However, by including an arbitration clause, parties clearly demonstrate the necessity of submitting the dispute to the referred arbitral tribunal [Born (2010), p. 4; Techniques l'Ingenieur, 1980 (France); E. Chang, p. 806; Montauk Oil, 1996 (USA); Tri-MG Intra, 2009 (Singapore)]. 75. Higher status is given to arbitration clauses as compared to jurisdictional clauses across judicial systems [Cohen, p. 471; ICC Award 6866/1992; Ryobi North American, 1996 (USA); BGH, 12.01.2006 (Germany); WSG Nimbus, 2002 (Singapore)]. Such an interpretation is based on the fact that the scope of the arbitration clause as an expression of the will of the parties is far wider than that of a jurisdiction clause [Gaillard/Savage, 490; E. Chang, p. 805; Brigif, 1997 (France)]. III. THE ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL HAS THE COMPETENCE AND JURISDICTION TO HEAR BOTH CLAIMS IN A SINGLE ARBITRATION 76. RESPONDENT seeks to thwart efforts for a speedy disposal of these claims by demanding different proceedings for each claim arising out of the FSA and the SLA. However, the tribunal has the jurisdiction to hear the matters together under the CEPANI rules [A.]. Further, the tribunal should hear the claims in a single proceeding in the interest of efficiency [B.]. Page | 16

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

A. THE TRIBUNAL HAS THE JURISDICTION AND THE COMPETENCE TO DECIDE THE

CLAIMS IN A SINGLE ARBITRATION

77. Art. 12 of CEPANI Rules confers jurisdiction on the tribunal to decide claims arising out of multiple contracts. As per Art. 10 (1) of CEPANI Rules, the tribunal can hear claims together if parties have submitted to CEPANI Rules and if the parties agreed to have their claims decided in a single arbitration. RESPONDENT argues that the claims under both the contracts are legally and factually separate. The requirement, for both claims to be heard together is that both the contracts under which disputes have arisen should be a part of a unified contractual scheme [1] and the claims be economically connected and indivisible [2.].

1. The FSA and the SLA are part of a unified contractual scheme

80. A unified contractual scheme refers to a situation where different contracts arise out of one relationship [Craig/Park/Paulsson, p. 94; SPP v Egypt, 1984 (ICSID)]. Under such circumstances, it is logical to have disputes adjudicated together [Leboulanger, p. 52; Schfer/Verbist/Imhoos, p. 34; Hanotiau (2006), 281]. Art. 10 (3) of CEPANI Rules states that if arbitration agreements concern matters that are not related to one another, it gives rise to a presumption against parties having consented to a single set of proceedings. However, if the matters are related to each other, the presumption stands rebutted. 81. The FSA and the SLA signed by parties in the present case are part of a single relationship. RESPONDENTs representative himself stated, It was [the parties] joint intention and understanding that the original purchase...was just a first step. Ultimately the entire facility was to be used for treatment of all kinds of cancer [Re. Ex. No. 2]. The parties had agreed to consider the Active scanning technology while signing the FSA, and had intensively discussed the possibility of adding a third room [RFA, 4, 9, 12]. The only reason why both contracts could not be entered together was budgetary restraints [Cl. Ex. No. 1; Cl. Ex. No. 4; RFA, 10]. 82. Recitals of the SLA itself specify that the general relationship between the parties is governed by the FSA which also provides the framework for the SLA. Presence of such a framework agreement and reference to each other is an indication of the unity of the operation and of the parties intent to have all disputes arbitrated together [Leboulanger, pp. 52-53; Mcllwrath/Savage, p. 72; Sayag, p. 81; ICC Award 1491/1992]. 2. The claims are economically connected and indivisible 83. Whenever there is an economic and operational unit hidden behind multiple contracts, that actually amounts to one fundamental single relationship [Leboulanger, pp. 46-47; Klckner, 1985 (ICSID); Holiday Inns, 1974 (ICSID); Francois-Xavier Train, p. 42]. In the instant case, the Proton Page | 17

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

Therapy Facility consists of four rooms, with a common proton accelerator [FSA]. The whole facility was designed and constructed in such a way as to allow for future expansion [Cl. Ex. No. 3]. Consequently, SLA led to the inclusion of a specialized cancer treatment technology in the third room [Cl. Ex. No. 4; Re. Ex. No. 2]. This reflects a single economic and operational unit divided only by monetary considerations, and consequently installed in two phases. 84. Moreover, when two claims are indivisible, i.e. they are all integrated parts of a single transaction, the disputes arising out of the related agreements should be treated as a whole [Leboulanger, p. 47; Kahn, pp. 15-17]. Also, various other contracts were entered into between the parties towards building of the Proton Therapy Facility [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 6]. The indivisibility is evident from RESPONDENTs own submission, as it states that termination of the FSA also leads to termination of the SLA, as one is useless without the other [Ans. to RFA, 23]. 85. RESPONDENT also contends that both claims should not be heard together as they are governed by different laws [Ans. to RFA, 12]. However, as per Art. 10 (2) of CEPANI Rules differences concerning the applicable rules of law are not material while determining the compatibility of both claims to be heard together. Moreover, agreements have been found to be compatible when different law was applicable to the merits of the dispute [Whitesell/SilvaRomero, p. 145]. B. THE TRIBUNAL SHOULD DECIDE THE CLAIMS IN A SINGLE ARBITRATION 86. CLAIMANT submits that multiple proceedings will defeat the motive behind a partys choice to arbitrate. A single set of proceedings also prevents conflicting awards [1.]. Moreover, RESPONDENT has contended that it agreed to arbitration because of the possibility of selecting different arbitrators on the basis of expertise required for a case [Ans. to RFA, 14]. CLAIMANT will prove that an arbitrator of different expertise may not be needed [2.]. There will be a substantial overlap of evidence between two disputes. A single set of proceedings is, therefore, a practicable solution which will improve efficiency of the arbitral process [3.]

1. Single set of proceedings prevents conflicting awards

87. Two proceedings arising out of a same set of facts may not provide the tribunal with a holistic view of the dispute. There will be influences exerted by the other claim which might not be perceptible, leading to the tribunal missing crucial facts [Pair/Frankenstein, p. 1062; Leboulanger]. On the contrary, a single set of proceedings reduces the risk of any factual errors and provides the tribunal with a wider perspective from which to draw its conclusions [Chiu, p. 43].

Page | 18

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

88. Therefore, assuming, the claims are heard in different proceedings, it is possible (although unlikely) that the award under the FSA is in favour of RESPONDENT and avoidance is held valid. Avoidance implies status quo and CLAIMANT will have to repay the amount received under the FSA, but will have the right to recover the goods provided there under [Art. 3.2.15(1), UNIDROIT]. It is definitely possible that under the SLA, the award could be in favour of CLAIMANT. CLAIMANT will then receive payment under the SLA. However, it would have removed the common proton accelerator under its right to restitution. Therefore, both the facilities would be rendered useless [Art. 59 r/w Art. 25 r/w Art. 81, CISG]. A single proceeding will avoid such absurd scenarios and allow arbitrators to harmonize the different laws applicable as well as prevent conflicting awards.

2. An arbitrator of different expertise may not be needed

89. RESPONDENT contends that the adjudication of two separate disputes i.e. in commercial viability of proton treatment facility under the FSA and software engineering under the SLA, requires arbitrators of different expertise [Ans. to RFA, 13]. RESPONDENT assumes that submission to arbitration provides it with a choice of different arbitrator(s) based on the different nature of a claim; commercial expertise and software expertise. 90. However, if separate proceedings are held, Prof. Bianca Tintin who is not a technical expert, will nevertheless have to determine the efficacy of the technical aspects of the proton therapy facility. She will need to determine if there was in fact misrepresentation of the cost/benefit analysis or did the facility not operate to the optimum level [Ans. to RFA, 22]. The latter requires technical expertise which is likely to be met by relying on expert witness etc. Moreover, claims of different nature can arise out of the FSA itself, wherein RESPONDENT will not have the luxury of arguing for separate tribunals based on the expertise needed. Therefore, the requirement of different expertise in itself does not result in bifurcation of the claims. 91. When claims of technical nature arise in a dispute, tribunals have adopted a practice of taking expert evidence on those matters [Waincymer, p. 931]. Art. 23 (2) of CEPANI Rules itself provides for appointing of experts to assist the tribunal. Similarly, IBA Rules on the Taking of Evidence in International Arbitration also allow for experts to report to the tribunal on specific issues designated by the arbitral tribunal [Art. 6, IBA Rules]. On one hand, expert evidence is a practical alternative which does not result in delay and other complications. On the other hand, it achieves the purpose for which the RESPONDENT, sought to appoint a different arbitrator.

Page | 19

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

3. Single set of proceedings leads to greater efficiency

92. As commercial entities, parties would always select an efficient resolution of disputes from the outset [Waincymer, p. 497]. A single set of proceedings is a commercially sensible option as it saves time, reduces overall legal fees and other costs that might arise out of another set of arbitral proceedings [Blackaby et al, p. 174; Born, p. 1111]. Consequently, it facilitates good administration of justice as a witness or expert does not have to give multiple testimonies, while the tribunal can pass more effective interlocutory orders [Veeder, p. 319; Chiu, p. 55]. 93. There are common operation elements between the FSA and the SLA, such as the proton accelerator, interface with the hospital software etc. Therefore, while determining the conformity of the goods supplied under each contract, there is likely to be an evidentiary overlap while deciding each claim. The tribunal will save time by deciding on these common factors in a single proceeding. Moreover, information exchange between different proceedings in the instant case will violate confidentiality requirements [Pryles/Waincymer, p. 64].

ARGUMENTS ON DETERMINATION OF APPLICABLE LAW

94. The only task before the tribunal in the current phase of the proceedings, is to determine the law applicable to the SLA [Proc. Ord. No. 1, 1]. The applicable law will, in turn, determine the liability of parties in subsequent proceedings. 95. Since arbitral tribunals are not organs of state, their starting point in determining applicable law is the relevant provision within arbitration laws and rules applicable to proceedings [Schwenzer/Hachem in Schlechtriem/Schwenzer (2010), p. 23]. As such, tribunals must give effect to intention of parties for determining the law governing the merits of the dispute [Art. 28, DAL]. 96. The intention of the parties is reflected by the choice of law clause contained in Sec. 22 of the July 2011 T&Cs which provides for the application of the law of Mediterraneo. The effect of this choice of law clause is that the CISG is applicable [VI.]. The T&Cs that embody the choice of law clause have been validly incorporated into the SLA [V.]. Further, the SLA satisfies the general requirements of applicability under the CISG [IV.]. 97. The question of valid incorporation of the standard terms must be determined under the assumption that the CISG is in principle applicable to the contract [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 2]. Therefore, CLAIMANT will first address the issue of whether the SLA lies within the sphere of applicability of the CISG. IV. THE SLA LIES WITHIN THE SPHERE OF APPLICABILITY OF THE CISG Art. 1 of the CISG. RESPONDENT has made a two-fold argument to assert that the SLA lies Page | 20 98. CLAIMANT notes that RESPONDENT has not disputed the internationality requirement under

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

outside the sphere of the CISG, questioning the applicability ratione materiae. It contends that the CISG is not concerned with sale of intangibles and therefore a software transaction lies outside its scope. Further, RESPONDENT also objects to licensing of software being a sale under the CISG [Ans. to RFA, 19]. 99. CLAIMANT will prove that the software under the SLA, despite being electronically transmitted, qualifies as goods within the CISG [A.]. CLAIMANT will also show that Art. 2 of the SLA, which provides for a license to use the software, is a valid sale of the software [B.]. CLAIMANT admits that the SLA is a mixed contract which provides for services along with a sale of goods. RESPONDENT has made certain contributions, under Art. 10 of the SLA. As such, RESPONDENT may also argue that it is excluded from the CISG by virtue of its Art. 3. However, CLAIMANT will show why the tribunal must hold to the contrary [C.]. A. ELECTRONICALLY TRANSMITTED CISG. 100. CLAIMANT contends that the tribunal must hold software to be goods irrespective of its apparent intangibility and peculiar mode of delivery. The software delivered under the SLA fulfils all requirements for goods under the CISG. In its characterization as goods, the intangibility of software must not be a hurdle [1.]. The main part of the software was downloaded by CLAIMANTs engineers from their servers [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 23]. RESPONDENT may argue that because it is electronically transmitted, it would fall outside the CISGs scope. However, CLAIMANT will show that the CISG governs the sale of electronically transmitted software [2.].

SOFTWARE QUALIFIES AS GOODS WITHIN THE

1. Software under the SLA qualifies as goods irrespective of intangibility.

101. The CISG does not define goods, but it is possible to arrive at certain parameters for goods from within the CISG itself [Diedrich (2002), p. 57]. According to Arts. 30 and 53 of the CISG, anything which can be commercially sold, and in which property can be transferred, can be the subject matter of a sale of goods. No reason can be derived from the CISG to limit its sphere of application to tangible things [Diedrich (2002), p. 64; Primak, p. 222]. Art. 2 of the CISG specifically excludes certain transactions, and it does not use intangibility as a criterion. Further, the list is exhaustive, not inclusive. 102. RESPONDENT seems to believe that the CISG must not apply to intangibles. RESPONDENTs misguided belief is not entirely baseless. Both civil and common law systems require physical possession for goods [Benjamin, pp. 61-62; Sergeyev/Tolstoy, p. 13]. Assuming that possession is not possible for intangibles, these legal traditions assert that intangibles must always be outside the scope of goods. However, academic opinion suggests that legal notions Page | 21

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

of tangibility need to be updated in order to conform to the complexities of digital age, to accommodate new products like software [Green/Saidov, p. 165; Kroll/Mistelis/Viscasillas, p. 60]. 103. It is inappropriate to assume that software is intangible and not capable of being possessed. Software is not merely an idea or a right, it is an arrangement of matter that is ultimately placed on some tangible medium [Koenig, p. 2605; Green/Saidov, p. 166; South Central Bell, 1994 (USA)]. Software takes the form of, what is called bits. These bits are stored on pits in the surface (CD-ROM), series of magnetic switches (flash drives), or series of electric pulses (electronic downloads) [SC Green; Davidson, pp. 341-342]. In the case at hand, it exists as preinstalled in the components, and the remaining part as downloaded from CLAIMANTs server [Proc. Ord. No. 2, 23]. Since, RESPONDENT possesses the equipment on which the software is downloaded, it would naturally possess the software as well. RESPONDENT can therefore control it and exclude others from it. RESPONDENT can move it to a different system, and can even transfer it. 104. Further, it is important to consider what the transaction is about. Under the SLA, RESPONDENT is not interested in the intangible knowledge or information. RESPONDENTs interest is to obtain recorded knowledge stored in some sort of physical form that the equipment could use. It is therefore obvious that the software is not just information to be comprehended [Shontz, p. 168]. If it were, it would have no use. Rather, the software is given physical existence to make certain desired physical things happen [South Central Bell, 1994 (USA)]. In this case, the desired physical thing is the modelling and steering of the proton beam [RFA, 11; Proc. Ord. No. 2, 22]. Software under the SLA is thus movable, transferrable, and capable of being possessed. The tribunal should find no basis to treat it differently [Graphiplus case, 1995 (Germany)].

2. The tribunal must apply the CISG to electronically transmitted software

105. It is accepted across jurisdictions that software delivered in a tangible medium, such as a disk or a tape, is a sale of goods [Schlechtriem (2005), p. 786; Tata Consultancy Services, 2005 (India); Advent Systems, 1991 (USA); Dynamic page printer case, 1996 (Germany)]. CLAIMANT submits that the aforementioned view is partially correct, but only to the extent that it holds software to be goods. In fact, there is no basis in relying on mode of delivery to characterise software. 106. The purpose behind buying a software remains unchanged irrespective of the mode of delivery. Indeed, academicians have criticised this unfortunate situation where law changes with respect to a software transaction with change in mode of delivery [Green/Saidov, p. 166; Cox in sec. V]. RESPONDENTs interest is merely in calibrating the proton beam. The record Page | 22

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

reflects no evidence of RESPONDENT having shown interest in medium of delivery of software. Consequently, the software can be transferred in any form, pursuant to the needs and conveniences under the contract [Diedrich (2002), p. 64]. 107. Even if CLAIMANT delivered the software in a tangible medium, it would ultimately be stored in the memory of RESPONDENTs system delivered by CLAIMANT. The medium would therefore be separated from the software [Cox in sec. I]. Further, the medium is almost always of little value as compared to its content and hence, of no relevance [Horovitz, p. 133]. A scholar drew an analogy of this unjustified classification on the basis of delivery, as differentiating between beer sold in a bottle and from the tap [Diedrich (2002), p. 64]. 108. RESPONDENT might have the tribunal believe that the exclusion of electricity under Art. 2 of the CISG would imply that the software downloaded electronically is also excluded. However, as electricity is merely a medium for the software, it has to be disregarded. Such transfer can also be done via fibre-optics, cellular transmissions and other latest technologies. These could soon render electrical transmissions obsolete, and thereby avoid this apparent restriction under the CISG [Larson, p. 471]. 109. Moreover, Art. 7(1) of the CISG requires that the application of CISG must be made with due regard to promoting uniformity in its interpretation. When the buyers intent remains the same in every case, the tribunal must not contravene Art. 7 to exclude software from goods on the basis of mode of delivery [Schlechtriem (2005), p. 790; Diedrich (1996), p. 324]. B. ART. 2 OF THE SLA CONSTITUTES A VALID SALE OF THE SOFTWARE 110. The software has been transferred subject to Art. 11 of the SLA, wherein the buyer will not have any intellectual property rights over the technology. Further, the buyer is authorised to the permanent use of the software till the entire life of the Proton Facility, for a one-time fee, and no royalties [Art. 2, SLA]. RESPONDENT may question that such limited transfer of ownership does not constitute sales. This, however, would be based on a wrongful belief that licences are not sales under the CISG [Lookofsky (2003), at fn. 76; Primak, p. 221]. CLAIMANT will prove that the license is covered under the CISG, by showing that it is in fact a sale under the CISG [1.]. CLAIMANT will also show that it was under no obligation to transfer intellectual property in the software, to constitute a sale [2.].

1. The software licence is a valid sale in the sense of the CISG

111. The CISG obligates the seller to deliver the goods, hand over any documents relating to them and transfer the property in the goods under its Art. 30. Art. 53 of the CISG requires the buyer to pay the price for the goods and take delivery of them. Therefore, any transaction may be classified as a sale if the mutual obligations of the parties consist of the delivery of goods , Page | 23

NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, DELHI

MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT

including the transfer of property in them, and on the other hand, the payment of the price for them [Honnold, p. 63; Ferrari (1995), p. 52]. 112. A licence entitles the licensee to have possessory and proprietary interest in that copy of the software which he has received. The right to exploit the uniqueness of the software still remains with its creator [Lookofsky (2003), p. 277]. This however, does not take away any rights from the buyer/licensee, who owns his copy of the software [Green/Saidov, p. 177]. The software can be used for the entire life of the facility [Art. 2, SLA]. Thus, CLAIMANT has no realistic expectation of the softwares return. Further, CLAIMANT has received a one-time payment for it. This makes the licence an economic equivalent of sale [Horovitz, p.156; Primak, p. 221].

2. CLAIMANT is not under any obligation to transfer intellectual property under a sale