Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

Încărcat de

Ambreen AtaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

Încărcat de

Ambreen AtaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Research

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

GENDER DIFFERENCE: WORK AND FAMILY CONFLICTS AND FAMILY-WORK CONFLICTS

Sadia Aziz Ansari Department of Business Psychology College of Business Management, Karachi Abstract The present study was conducted to explore the prevailing differences between work-to-family interference, and family-towork interference among men and women employees. The population was a random sample of 210 men and women employed in Karachi aged 2550 years. Work-family conflict, and familywork conflict was measured by (Niemeyer, Boles, & Mcmurrian 1996) 10-item scale, which was scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Data collection also included questions about their current functioning with regard to family support, control over work responsibilities and work hours flexibility along with demographic questions about, age, gender, education, marital status, number of dependents and nature of employment. Data was analyzed through descriptive statistics to assess prevalence of work-tofamily interference and family-to-work interference. Overall results indicate no significant gender difference with regard to work-family interference and family-to-work interference. This is theoretically an unexpected result, however, it might be due to the sample size which was too small to identify such differences. Further study is necessary to accurately identify the predictors of work-family interference and family-to-work interference in collectivistic societies. Key-words: Work-family conflict, family-work conflict, gender JEL Classification: A13, J16, Z13, R20, M15

*An earlier version of this refereed pa per wa s presented a t the first Bu siness Psychology Semina r held by the Department of Business Psychology IoBM in November, 2010

315

PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

Research

Eclectic Literature Review: In the recent past most of the research in the domain of work and family has been originated within diverse disciplines like sociology, psychology, occupational health, business management, and gender and family studies. Work and family symbolize two of the most critical roles of an adult life. Its obvious that work can interfere with family and family can interfere with work, factors like globalization, equal employment opportunities, working hours, and changes in the demographic makeup of employees have posed significant challenges for both organizations and employees. In particular, with the increase in dual-career households, employees are ever more performing both work and family roles all together and dealing with job-related demands that place limits on the performance of family role and vice versa. Hence; researchers are primarily interested in identifying causes of work-family interference. The work-family interface is defined as a unified relationship between work and family. Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, and Rosenthal, (1964); first examined this inter-role conflict that people experienced between their work roles and other life roles. Later Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) defined work-family conflict (WFC)as, a form of inter-role conflict in which role pressures from the work and family domain are mutually incompatible in some respect competing work activity or when family stress (FWC) has a negative effect on performance in the work role. There are three aspects of the work-family interface that are related to conflict: (1) bidirectional nature (Carlson & Kacmar, 2000), (2) time, and (3) psychological carryover (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985; Piotrkowski, 1979; Voydanoff, 1988). Work -family conflict is explained as reciprocal interference of work and family roles leading to significant personnel and organizational problems. Studies focusing on role stress have suggested that employees are frequently confronted with role stress, heavy workloads, long PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011 316

Research

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

work hours, irregular work schedules, job insecurity and are at risk of conflict in the work-family interface (Karatepe & Baddar, 2006; Karatepe & Sokmen, 2006; Namasivayam & Mount, 2004). A group of authors including: Carlson and Kacmar (2000); Eagle, Icenogle, and Maes (1998); Eagle, Miles, and Icenogle (1997); Frone, Yardley, and Markel (1997); Greenhaus and Powell, (2003); Gutek, Searle, Klepa, (1991); Matsui, Ohsawa, and Onglotco (1995); Netemeyer, Boles, and McMurrian (1996); Williams and Alliger, (1994) agreed that conflict in the work-family interface has a bidirectional nature. Such as Frone, Russell and Cooper, (1992) have shown that work-family conflict and familywork conflict as the two forms of inter-role conflict. Where workfamily conflict refers to a form of inter-role conflict in which the general demands of time devoted to, and strain created by the job interfere with performing family related responsibilities; and family-work conflict refers to a form of inter-role conflict in which the general demands of time devoted to, and strain created by the family interfere with performing work-related responsibilities (Netemeyer, Boles, & McMurrian, 1996). Similarly, Greenhaus and Powell (2003) showed that work-family conflict occurs when participation in work activity interferes with participation in a competing family activity or when work stress has a negative effect on behavior within the family domain. For example, conflict may occur when an employee is accepting a promotion that requires more hours which in turn decreases the number of hours at home with the family. On the other hand, family-work conflict is experienced when participation in a family activity interferes with participation in a competing work activity or when family stress has a negative effect on performance in the work role. Industrial and organizational psychologists and other researchers have attempted to better understand work-family 317 PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

Research

conflict construct by examining the bidirectionality of work family conflict, different types of conflict, several reactance models of work-family conflict, and different causal models explaining how conflict affects individuals. However, gender differences in work and family conflict have been a consistently important theme in work-family research (Lewis & Cooper, 1999). Pleck (1977) considered gender as an important factor in work-family conflict in his theory of the work-family role system. He has conceptualized work-family interface that includes gender as an important factor. Further he explained that the work-family role system is composed of the male work role, the female work role, the female family role, and the male family role. Each of these roles may be fully actualized, or may be only partly actualized or latent, as is often the case with the female work role and the male family role. According to Lambert (1990) gender differences must be studied in depth. Extensive review of the literature has suggested two hypotheses concerning gender differences in domain source conflict: domain flexibility and domain salience. The domain flexibility hypothesis predicts that the work domain is a greater source of conflict than the family domain for both women and men. The domain salience hypothesis predicts that the family domain is a greater source of conflict for women than the work domain and the work domain is a greater source of conflict for men than the family domain. Izraeli, (1993); Evans & Bartolome (1984) assumed that the work domain is less flexible, thus work affects family life more than vice versa and there is no gender differences. Contrary to this, Cooke and Rousseau (1984) proposed that conflict is greater from the domain that is more salient to the persons identity. Therefore, women experience more conflict from the family domain and men from the work domain. Hall (1972) noted that women may experience more role conflict as a result of simultaneity of their multiple roles. Beside gender, some family domain pressures like the effect of presence of young children (Lewis & Cooper, 1988); (Kopelman & Greenhaus,1981), PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011 318

Research

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

spouse time in paid work (Coverman & Sheley, 1986); (Voydanoff, 1988) and work domain pressures like number of hours worked per week (Voydanoff, 1988); (Burke,Weirs & Duwors,1980) are associated with work family conflict. Moreover, studies have shown that employed women generally face more demands (from paid work, child care, and housework) than employed men (Robinson & Godbey, 1997). The degree of this difference for women is made up by housework: when men and women differ on number of hours dedicated to housework, flexibility of the activity, and the challenging and or creativity of the task. Hochschild (1989) also reported that employed mothers work an extra month per year of 24 hour days when compared with employed fathers with their number of hours dedicated to housework. Similarly, research has shown that men do not adjust the time that they spend on home and family activities according to their wives employment decisions (Shelton & John, 1996). Consequently, even if women increase the number of hours they work, men are not likely to spend more hours on housework. Its not just time that leaves women with the feeling of imbalance. Housework is gendered that is, there are tasks that women are expected to perform and others that are generally mens expected responsibility. Women cook, clean, and care for children, while men usually take care of home repairs and lawn maintenance, (Robinson & Godbey, 1997). In this regard male activities are more flexible while female responsibilities are often necessary to do every day. Therefore men do their tasks as leisure-like and discretionary activities (Larson, Richards, & Perry- Jenkins, 1994); (Shaw, 1988). Greenhaus and Beutell, (1985), and many scholars have hypothesized that women experience more work-family conflict than men because of their typically greater home responsibilities and their allocation of more importance to family roles. However, more recent researchers have discovered that men and women do not differ on their level

319

PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

Research

of work-family conflict (Blanchard-Fields, Chen, & Hebert, 1997; Duxbury & Higgins, 1991; Rice & Frone , 1992; Wallace, 1997) On the basis of the above discussion the present study aims to explore gender and domain differences in work family conflict among women and men employees employed in Karachi. Specifically, this study attempts to scrutinize which of the two domains that is work-family conflict or family-work conflict, causes more conflict for men and women and examine gender differences on the basis of Niemeyer, scales measures of work-family conflict in Pakistani population. Hypothesis: 1. Null Hypothesis: There is no relationship between gender and the degree of work-family and family work conflict. Alternative hypothesis: There is a relationship (difference) between gender and the degree of workfamily conflict & family-work conflict. Null Hypothesis: There is no relationship between gender and the nature of work-family and family work conflict. Alternative hypothesis: There is a relationship between gender and nature of family-work conflict and work-family conflict.

2.

Methodology: The present study was conducted to observe gender differences pertaining to workfamily interference among employees both men and women from diverse professions which include: teachers, mangers, doctors, bankers and others. To assess work-family conflict (WFC) and family-work conflict, (FWC) Niemeyer, Boles, & Mcmurrians (1996), scale was used. It includes two subscales: WFC and FWC and each subscale consists of five items with 7-point likert rating scale ranging from strongly PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011 320

Research

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

disagree to strongly agree where 1= strongly disagree, 2= disagree, 3= slightly disagree, 4= neutral, 5= slightly agree, 6= agree and 7= strongly agree. Niemeyer, Boles, & Mcmurrian (1996), described high internal consistency of five items subscales for both WFC and FWC that is Cronbach alpha range from .82 to .90. The scale measures the respondents degree of agreement with statements. The scale scores range from 5 to 35, a high score indicates a high level of perceived conflict between WFC and FWC, while a low score reflects a low level of perceived conflict between WFC and FWC. Along with the work-family conflict scale, demographic questions about age, gender, education, marital status, number of dependents and nature of employment were asked. The demographic section also included eight moderating variables including: respondents perceived family, friends and partners support for WFC & FWC, perceived control over work responsibilities, perceived flexibility in work hours, and perceived bosss support for both WFC and FWC measured through self-structured questions. Those eight questions are as follows: 1) on a scale from 1 (no control) to 7 (complete control), how much control do you have over your work responsibilities? on a scale from 1 (no flexibility) to 7 (complete flexibility), how would you describe your work hours? on a scale from 1 (no support) to 7 (complete support), how would you describe the level of support you feel you have from your partner for conflict that arises as a result of work interfering with family responsibility? on a scale from 1 (no support) to 7 (complete support), how would you describe the level of support you feel you have your partner for conflict that arises as a result of family responsibilities interfering with work? PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011

2)

3)

4)

321

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

Research

5)

on a scale from 1 (no support) to 7 (complete support), how would you describe the level of support you feel you have from your family members and friends for conflict that arises as a result of family responsibilities interfering with work? on a scale from 1 (no support) to 7 (complete support), how would you describe the level of support you feel you have from your family members and friends for conflict that arises as a result of family responsibilities interfering with work? on a scale from 1 (no support) to 7 (complete support), how would you describe the level of support you feel you have from your boss/supervisor for conflict that arises as a result of work interfering with family responsibilities? on a scale from 1 (no support) to 7 (complete support), how would you describe the level of support you feel you have from your boss/supervisor for conflict that arises as a result of family responsibilities interfering with work?

6)

7)

8)

T he targeted population was both men and women, regular full time employees, working in Karachi. The sample was a random selection consisting of 105 men and 105 women (N=210), age ranged 2550 years. The study was con duct ed t hr ough on e t o on e cont a ct . Pa rt i cipa nt s completed the work-family conflict, family-work conflict and demographic questionnaire. All the data was collected by going into the field during September, 2010.

PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011

322

Research

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

Results & Discussion: Table 1: Descriptive statistics for demographic variables (age, gender, marital status, educational level, no of children and nature of employment)

Demographic Characteristic N= Gender Age ( M=26.4yrs )

Frequency 210 Male= 105 Female= 105 20-25= 73 26-30=56 31-35=20 36-40=26 41-45=11 46-50= 24 Married= 120 Single= 90 Masters=78 Graduate =58 Intermediate=34 Matric =23 Others=17 0= 66 1=11 2=27 3= 11 4= 5 Full time= 164 Part-time= 44 No answer=2

Marital status Education level

No of children

Nature of employment

50% 50% 34% 26% 9.5% 12.5% 5.% 11.3% 57% 42% 37% 27% 16% 10% 8% 55% 9% 22% 9% 4% 78% 20% 0.9%

Data was analyzed through descriptive statistics to analyze the demographic characteristics of sample and moderating variables. 26.4 years appeared as an average age of respondents. Demographic findings show that most of the participants i.e. (57%) are married and (55 %) of married respondent have no children. On the other hand, the remaining married respondents have respectively two (22%) , three (4%) 323 PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

Research

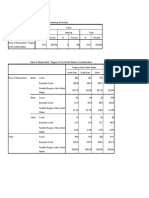

and one (9%) as number of children, this reflects that just 4% of the total married population possessed somewhat large family size with four children. The rest of total respondents i.e. (47%) are single. Among all respondents (37%) have completed their masters, (27%) graduate, (16%) intermediate and (10%) matric as their last educational qualification (see table 1.1). Table 2: Descriptive statistics for Eight moderating factors for FWC & WFC Variables Male Female m m Control over work responsibilities 5.5 3 5.27 Working hours Flexibility 4.59 4.4 Perceived partners Support for WFC 5.05 5.27 Perceived partners Support for FWC 4.8 5.2 Perceived Friends & Familys Support 5.0 5.2 for WFC Perceived Friends & Familys Support 4.8 5.1 for FWC 4.4 4.5 Perceived Boss Support for WFC Perceived Boss Support for FWC 4.2 4.5 Table1.2 presents the mean values for all moderating variables which work as buffer to WFC & FWC including work hour flexibility, control over work responsibilities, family, partner, friends and bosss support for the work-family and family-work conflicts. Social support and relations with co-workers and managers is an important part of an individuals social environment and lack of it can be a contributing factor to their stress. Our findings clearly support this argument as most of the respondents experienced moderate level of WFC (mean=21) & FWC (mean=17.8). Where 19 is the 50th percentile for FWC score and 22 is the 50th percentile for WFC score distributions. This indicates that about half of the total respondents scores on WFC & FWC scale are either less or equal to 19 and 22 (see Table1.3). Furthermore, standard deviation for FWC (std. deviation = 6.3) and (std. deviation = 5.7) for WFC which indicates that majority of respondents scores dont fall into the mean scores for both FWC and WFC scores. Moreover, this is also supported when both male and female respondents of the study received complete PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011 324

Research

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

support from their husbands, family members and friends i.e. (5.2%). All respondent irrespective of the gender reported that they receive higher level of support and encouragement from their families, friends and partners when work and family domains become troublesome. On the contrary, most of the participants received moderate level of their bosss support i.e. (4.5%) to manage with WFC & FWC. The amount of support received by men and women from their bosses is found relatively the same i.e. (4.2%). In general there is a relation between responsibility and control when it comes to work. If individuals have lots of responsibilities at their jobs and little or no control over it to have it interfere more with work as well as family obligations than control at work responsibilities. Respondents of this study reported that they have enough control i.e. (5.5%) over their work responsibilities and can also work with flexible working hours. Furthermore, for women flexibility at work i.e. (4.4%) reduces the amount of family work conflicts when they are able to determine the hours they work in which moderates the WF & FW interference. Table 3: Descriptive Statistics for Work-Family Conflict & Family-Work Conflict

Percentiles 25 50 75 All respondents Mean score Std. Deviation Std. Error Variance Male Female

325

FWC 13 19 23 17.83 6.36 0.43 40.45 17.5 18.1

WFC 17 22 25 21 5.75 0.39 33 20.5 21.4

PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

Research

Table 4: Chi-Square Tests (SPSS 17.0)

Asymp . S ig. (2sided) .42 3 .15 8

Value Pearson C hi-S quare Likelihood Ratio N of Vali d C ases 26.7 35

a

df 26 26

33.125 21 0

a. 3 2 cells (59.3%) hav e expected count less than 5. The mi nim um expected count is .50.

Chi-square was analyzed through (SSPS 17.0) to test the hypothesis. It was hypothesized that there is no relationship between gender and the degree of work-family and family work conflict which is rejected at alpha (p=0.05 level> X2=26.7). The probability of the chi-square test statistic p=38.8, at the alpha level of significance of 0.05 was greater for FWC & WFC (chi-square=26.7), therefore, the null hypothesis was accepted (see Table 4). It was also hypothesized that there is a relationship between gender and the type of workfamily and family work conflict as women experience more family-work conflict and men experience more work-family conflict this hypothesis was also rejected at alpha (p=0.05 level> 38.8). The probability of the chi-square test statistic p=38.8, at the alpha level of significance of 0.05 was greater for FWC & WFC (chi-square=23), therefore, rejected the research hypothesis. The research hypothesis that differences in degree of perceived work-family and family- work conflicts are related to differences in gender is not supported by this analysis (see Table 5).

PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011

326

Research

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

Table: 5 Chi-Square Tests (SPSS 17.0)

Chi-Square Tests Value df Asymp. Sig. (2-sided)

Pearson Chi-Square 23.048 a 24 .517 Likelihood Ratio 26.120 24 .347 N of Valid Cases 210 a. 29 cells (58.0%) have expected count less than 5. The minimum expected count is .50.

These findings are more in the line with previous studies that there were no differences between the gender in experience of work-family conflicts. Even which present findings dont support that family is the greater source of conflict for women and work for men. Furthermore, source of family-work conflicts are associated with moderating variables like the number of small children, number of children and time spent at work. Since majority of respondents are married with no children might be the indicative of rejection. When it is even contrary to our societal gender role expectations and responsibilities; women carry out most of the family responsibilities from child care to the household. In this way these findings can support little when most of the respondents are young with small family size hence the family doesnt generate enough pressures when it clashes with their work responsibilities. This is also an indicative of evolving family- friendly organizations in Pakistani society. Social support i.e. family, friends, partner and bosss support is generally considered a moderator between stress and conflicts; individuals who receive high support experience low strain than others. This is also comparable to the respondents in the present study.

327

PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

Research

When both male and female respondents equally perceived that they have enough control over their current work responsibilities and working hour flexibility and appeared as dominating moderating factors for WFC and FWC in the present study. It also indicates that working environment in industries like academia, health and banks is becoming conducive to work in our local context. H owever, with a small and convenient sampling generalization of the results hold limitations of the study. Moreover, unequal distribution of sample from different and specific occupation also resulting limits to the generalization. On the basis of above discussion we conclude that sources of WFC & FWC can be better examined if employees are with comparable occupational and of employment status. Such as Karaseks theory, suggested that lower level managers reported higher levels of conflict than others. Therefore, there is still a need to study work family conflict construct in detail and identify what those different organizational and moderating variables like support, controllability and work hour flexibility, work load, and work environment to determine gender differences for WFC and FWC. Future research may also focus on exploring the factor analysis and convergent-validity of two different constructs such as Carlson scale for its local implication so that it can be brought into human resource management functions.

PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011

328

Research

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

References: Burke, R. J., Weir, T., & DuWors, R. E.(1980) Work Demands on Administrators and Spouse Well-being. Human Relations, 33, 253-278. Carlson, D. & Kacmar, M. (2000) Work-Family Conflict in the Organization: Do Life Role Values Make a Difference? Journal of Management, 26(5), 1031-054. Carlson, D. (1999) Personality and Role Variables as Predictors of Three Types of Work Family Conflict, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 55, 236-253. Cooke, R. A., & Rousseau, D. M. (1984), Stress and Strain from Family Roles and Work-role Expectations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 252-260. Elizabeth, D.L., & Alan, H.C., (1991), Gender Differences in WorkFamily Conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(1): 60-74. Eagle, B.W., Icenogle, M. L. & Maes, J. D. (1998) The Importance of Employee Demographic Profiles for Understanding Experiences in Work-family Interrole Conflicts. The Journal of Social Psychology, 138: 690-709. Eagle, B.W., Miles, E. W., & Icenogle, M. L. (1997) Interrole Conflicts and the Permeability of Work and Family Domains: Are there gender differences? The Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50: 168-184. Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, L., (1992) Prevalence of Work Family Conflict: are Work and Family Boundaries Permeable. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 723-729.

329

PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

Research

Frone, M. R. & Yardley, J. K. (1996). Workplace Family-supportive Programmes: Predictors of Employed parents Importance Rating. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 351-366. Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985),Sources of Conflict Between Work and Family Roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76-88. Greenhaus, J. & Powell, G. (2003), When Work and Family Collide: Deciding between Competing Role Demands. Organizational Behavior and the Human Decision Processes, 90(2): 291-303. Gutek, B. A. Searle, S. & Klepa, L. (1991), Rational versus Gender role Explanations for Work-Family Conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 560-568. Hall, D. T. (1972) A Model of Coping Hall with Role Conflict: The Role Behavior of College Educated Women. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17, 471-489. Hochschild, A. (1989) The second shift. New York: Avon Books. Kahn, R., Wolfe, D., Quinn, R., Snoek, J. & Rosenthal, R. (1964) Organizational Stress, Wiley, New York. Kopelman, R. E., Greenhaus, J. H., & Connolly, T. F. (1983) A Model of Work, Family, and Interrole Conflict: A Construct Validation Study. Organizational, Behavior, and Human Performance, 32, 198-215. Lambert, S. J. (1990), Process Linking Work and Family: A Critical Review and Research Agenda, Human Relations, 43(3), 239-257.

Larson, R. W., Richards, M. H., & Perry-jenkins, M. (1994) Divergent worlds: TheDaily Emotional Experienceof Mothers and Fathers in The Domestic and Public Spheres.

PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011 330

Research

Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work Conflicts

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67: 1034-1046. Matsui, T., Ohsawa, T., & Onglotco, M. (1995) Work-family Conflict and the Stressbuffering Effects of Husband Support and Coping Behavior among Japanese Married Working Women. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 47: 178-192. Netemeyer, R.G.,Boles, J. S. & McMurrian, R. (1996).Development and Validation Of Workfamily Conflicts and Work-Family Conflict Scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 400 410. Pleck, H., (1977), The Work-Family Role System. Social Problems, 417-427. Rice, R. W., Frone, M. R., & McFarlin, D. B. (1992) Work-Nonwork Conflict and the Perceived Quality of Life. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 155-168. Robinson, J. P., & Godbey, G. (1997) Time for life. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. Shelton, B. A., & John, D. (1996) The Division of Household Labor. Annual Review of Sociology, 22: 299-322. Voydanoff, P. (1988) Work Role Characteristics, Family Structure Demands and Work Family Conflict. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50, 749-761. Williams, K. J., & Alliger, G. M. (1994) Role Stressors, Mood Spillover, and Perceptions of Work-family Conflict in Employed Parents. Academy of Management Journal, 37: 837-868.

331

PAKISTAN BUSINESS REVIEW JULY 2011

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Chi Square Assignment MOHA 570Document3 paginiChi Square Assignment MOHA 570Tony GiancasproÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stereotyping Research Paper Assignment SheetDocument2 paginiStereotyping Research Paper Assignment Sheetapi-253297734Încă nu există evaluări

- UNWTO Tourism 2020Document28 paginiUNWTO Tourism 2020Sofija Petronijevic100% (1)

- A Study On Awareness of Personal Financial Planning Among Households in Visakhapatnam CityDocument11 paginiA Study On Awareness of Personal Financial Planning Among Households in Visakhapatnam CityarcherselevatorsÎncă nu există evaluări

- WFC and FWCDocument21 paginiWFC and FWCSaleem AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consequences Associated With Work-To-Family ConflictDocument31 paginiConsequences Associated With Work-To-Family ConflictMercedes Baño Hifóng100% (1)

- Work Family ConflictDocument7 paginiWork Family ConflictslidywayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Work Family Conflict and Work Related Withdrawal BehaviorsDocument18 paginiWork Family Conflict and Work Related Withdrawal BehaviorsClayzingoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Social Loafing Job Insecurity PDFDocument9 paginiJurnal Social Loafing Job Insecurity PDFnurita radhikaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Work Family ConflictDocument19 paginiWork Family ConflictMaulik Rao100% (1)

- 4M2 Group 7 PepsiDocument7 pagini4M2 Group 7 PepsiLian ChuaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self Visionary For Maga Final Na Talaga ToDocument13 paginiSelf Visionary For Maga Final Na Talaga ToDiane Leslie EnojadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Red Hot StoveDocument11 paginiThe Red Hot StoveTina TjÎncă nu există evaluări

- Equipment ### Accounts Payable ### P120,000 / 30 + P4,000 A MonthDocument10 paginiEquipment ### Accounts Payable ### P120,000 / 30 + P4,000 A MonthShaina AragonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Job SecurityDocument17 paginiJob SecurityAndrei Şerban ZanfirescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Conflict AnalysisDocument15 paginiUnderstanding Conflict AnalysisAssegid BerhanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principles of Tourism 1Document7 paginiPrinciples of Tourism 1GinnieJoy100% (1)

- Expand market and reduce costs through brand diversificationDocument2 paginiExpand market and reduce costs through brand diversificationJKÎncă nu există evaluări

- L4 Travel MotivationDocument35 paginiL4 Travel MotivationMatthew Rei De LeonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Covid 19 Pandemic Implications On HRM AnDocument14 paginiCovid 19 Pandemic Implications On HRM AngygyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smit Student Handbook AppsDocument42 paginiSmit Student Handbook AppsASLAMIA UKOMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis TitleDocument5 paginiThesis TitleAilyn TamaresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tourism Concepts ExplainedDocument22 paginiTourism Concepts ExplainedChandima BogahawattaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Housekeeping and Bed Making CompetitionDocument1 paginăHousekeeping and Bed Making CompetitionMary Abigail Collado AntolinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pepsi Marketing From PakistanDocument73 paginiPepsi Marketing From PakistanBill M.0% (1)

- Extra WorkDocument3 paginiExtra WorkSarfaraj OviÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Analysis Of: By: Bimple Fyee Leonor Bsa Iii Presented To: Dr. Antonio Agustin ProfessorDocument14 paginiAn Analysis Of: By: Bimple Fyee Leonor Bsa Iii Presented To: Dr. Antonio Agustin ProfessorBimple Fyee LeonorÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Impact of Employee Engagement On Task PerformanceDocument7 paginiThe Impact of Employee Engagement On Task PerformanceHazrat BilalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Study On Shakespearean SonnetsDocument4 paginiCritical Study On Shakespearean SonnetsAbhisek MukherjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- TilapiaDocument34 paginiTilapiaCherry Ann Pascua RoxasÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Sonnet 116 ShakspearsDocument5 pagini1 Sonnet 116 ShakspearsKhalid HidaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- The relationship between family interference and job performanceDocument54 paginiThe relationship between family interference and job performanceRuel AGABILINÎncă nu există evaluări

- El FCKN FilibusterismoDocument6 paginiEl FCKN Filibusterismojustine jeraoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Work-Family Conflict Theories ExplainedDocument2 paginiWork-Family Conflict Theories ExplainedFaseeh IqbalÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Accreditation Standards For Tour GuidesDocument34 paginiNational Accreditation Standards For Tour Guidesdufirt turcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abstract MS 2Document38 paginiAbstract MS 2Rocky YapÎncă nu există evaluări

- Green Ha Us Collins Shaw 2003, The Relation Between Work-Family Balance and Quality of LifeDocument22 paginiGreen Ha Us Collins Shaw 2003, The Relation Between Work-Family Balance and Quality of LifeAndreea Mădălina100% (1)

- Domingo, Julianna Am R. Humss 12-CDocument1 paginăDomingo, Julianna Am R. Humss 12-CJULIANNA AM DOMINGOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tourist Motivation Segments Nha TrangDocument42 paginiTourist Motivation Segments Nha TrangNguyen Phuong Thao100% (1)

- Wedding Program KCDocument2 paginiWedding Program KCRenato Orias Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- Template For ThesisDocument23 paginiTemplate For ThesisJoshua RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Traditions Fading as New Ideas Take OverDocument2 paginiTraditions Fading as New Ideas Take Overstevhuyn100% (1)

- Mayo's Human Relations Theory and the Hawthorne EffectDocument12 paginiMayo's Human Relations Theory and the Hawthorne EffectBuddha 2.OÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human Resources Practice and Organizational PerformanceDocument9 paginiHuman Resources Practice and Organizational PerformanceAre FixÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tourism As Income and Employment Generator: Observations On Baguio Flower FestivalDocument16 paginiTourism As Income and Employment Generator: Observations On Baguio Flower FestivalGemma ParanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motivation of Students To Study Tourism Hospitality ProgramsDocument11 paginiMotivation of Students To Study Tourism Hospitality ProgramsCherie OrpiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sexual HarrasmentDocument13 paginiSexual HarrasmentZabrinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pepsi MaxDocument17 paginiPepsi MaxWaqar Ali100% (1)

- JALINGODocument40 paginiJALINGODambo HussainiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Behind Closed DoorsDocument13 paginiBehind Closed DoorsRon Jacob AlmaizÎncă nu există evaluări

- NTDP Executive Summary PDFDocument13 paginiNTDP Executive Summary PDFBlincentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brand Equity in A Tourism Destination A PDFDocument18 paginiBrand Equity in A Tourism Destination A PDFMohammad Al-arrabi AldhidiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swot Analysis PepsiDocument14 paginiSwot Analysis Pepsivmd35sbsbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Financial Info MarketplaceDocument17 paginiFinancial Info MarketplaceAdi SusiloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter1 FinalDocument7 paginiChapter1 FinalRosemarie InojalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project Management - SolutionsDocument21 paginiProject Management - SolutionsBÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHY4U Unit 1, Assignment 1 Annotated Maps of InfluenceDocument3 paginiCHY4U Unit 1, Assignment 1 Annotated Maps of InfluenceAlyssaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marketing Strategies for Promoting Golden Triangle as a Top Tourism DestinationDocument15 paginiMarketing Strategies for Promoting Golden Triangle as a Top Tourism DestinationMd JahangirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Relationships of Work - Family Conflict With Business and Marriage Outcomes in Taiwanese Copreneurial WomenDocument13 paginiRelationships of Work - Family Conflict With Business and Marriage Outcomes in Taiwanese Copreneurial WomenKamboj BhartiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Work-Family Conflict On Organizational CommitmentDocument18 paginiImpact of Work-Family Conflict On Organizational CommitmentSaleem Ahmed100% (1)

- The Impact of Demoggraphic Factors On Family Interference With Work and Work Interference With Family and Life SatisfactionDocument8 paginiThe Impact of Demoggraphic Factors On Family Interference With Work and Work Interference With Family and Life SatisfactioninventionjournalsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Work Life Balance PDFDocument54 paginiWork Life Balance PDFMohammad TarequzzamanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Country of Origin Effect On Global BrandsDocument15 paginiCountry of Origin Effect On Global BrandsKomal MachaiahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Questionnaire Work Family ConflictDocument1 paginăQuestionnaire Work Family ConflictAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bba Vi ResultDocument3 paginiBba Vi ResultAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manager's Guide 4th Ed 09vDocument540 paginiManager's Guide 4th Ed 09vAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper EditDocument4 paginiPaper EditAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Competitive Pressure From The Sellers of Substitute ProductsgggDocument20 paginiCompetitive Pressure From The Sellers of Substitute ProductsgggAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ConsulDocument3 paginiConsulAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acct 620 Chapter 11Document33 paginiAcct 620 Chapter 11bobobuoboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Africa BW Exams Assistant JDFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFVDocument5 paginiAfrica BW Exams Assistant JDFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFVAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- FNJFNJFJNDocument4 paginiFNJFNJFJNAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MicrobiologyDocument1 paginăMicrobiologydangerurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acct 620 Chapter 11Document33 paginiAcct 620 Chapter 11bobobuoboÎncă nu există evaluări

- BA 469 Lecture Ch2Document35 paginiBA 469 Lecture Ch2Ambreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Work Fbjbhbamily BalanceDocument27 paginiWork Fbjbhbamily BalanceAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- HAUTE Chocolate Final1Document22 paginiHAUTE Chocolate Final1Ambreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2Document25 pagini2Ambreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Employee Training: Workplace DiversityDocument3 paginiEmployee Training: Workplace DiversityAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BA 469 Lecture Ch2Document35 paginiBA 469 Lecture Ch2Ambreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Articles BookDocument1 paginăArticles BookAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Relationship Betwenn Work-FamilybhDocument13 paginiRelationship Betwenn Work-FamilybhAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 BJHBHBHBDocument16 pagini4 BJHBHBHBAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Relevance Versus Convenience in Business Research: The Case of Country-of-Origin Research in MarketingDocument33 paginiRelevance Versus Convenience in Business Research: The Case of Country-of-Origin Research in MarketingAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planning A Business LetterDocument22 paginiPlanning A Business LetterAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ka Miner JJJDocument56 paginiKa Miner JJJAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Employee Relations Management Vision and ActionsDocument20 paginiEmployee Relations Management Vision and ActionsAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Articles BookDocument1 paginăArticles BookAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- E-Commerce Business ModelsDocument20 paginiE-Commerce Business ModelsAmbreen AtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swot Analysis Chocolate)Document13 paginiSwot Analysis Chocolate)preetifan100% (5)

- Products, Services, and Brands Building Customer ValueDocument41 paginiProducts, Services, and Brands Building Customer ValueAnup Kumar PrasaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- STA 220 Syllabus Spring 2018-1Document3 paginiSTA 220 Syllabus Spring 2018-1Anass BÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment 2 B.ed Code 8604Document15 paginiAssignment 2 B.ed Code 8604Atif Rehman100% (5)

- ProblemDocument1 paginăProblemLeonora Erika RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- LECTURE NOTES ON PARAMETRIC & NON-PARAMETRIC TESTSDocument19 paginiLECTURE NOTES ON PARAMETRIC & NON-PARAMETRIC TESTSDiwakar RajputÎncă nu există evaluări

- BAB 8 KTI Faisal IswandiDocument20 paginiBAB 8 KTI Faisal IswandiSari Ramadana SyukurÎncă nu există evaluări

- R8 PDFDocument14 paginiR8 PDF20040279 Nguyễn Thị Hoàng DiệpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Influence of Mother Tongue in The Teaching and Learning of English Language in Selected Secondary Schools in Ondo State, NigeriaDocument10 paginiInfluence of Mother Tongue in The Teaching and Learning of English Language in Selected Secondary Schools in Ondo State, NigeriakasmarproÎncă nu există evaluări

- (DM) Categorical Data Analysis (Agresti, 2002) Companion (S-PLUS and R)Document265 pagini(DM) Categorical Data Analysis (Agresti, 2002) Companion (S-PLUS and R)Luciene TorquatoÎncă nu există evaluări

- PHD - Advanced Educational StatisticsDocument8 paginiPHD - Advanced Educational StatisticsDenis CadotdotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Đại Học Quốc Gia Đại Học Bách Khoa Tp Hồ Chí Minh: Subject: probability and statisticsDocument8 paginiĐại Học Quốc Gia Đại Học Bách Khoa Tp Hồ Chí Minh: Subject: probability and statisticsTHUẬN LÊ MINHÎncă nu există evaluări

- WORD Costumes Satisfaction Towards Honda Due Scooters.Document78 paginiWORD Costumes Satisfaction Towards Honda Due Scooters.Kajal YadavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chi SquareDocument8 paginiChi SquareshalynÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chi-Square Test ExplainedDocument10 paginiChi-Square Test ExplainedCarla Pianz FampulmeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Probabilistic Models For Construction ProjectsDocument262 paginiProbabilistic Models For Construction ProjectsVijaya BhaskarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chi square test results for relationship between race and regionDocument4 paginiChi square test results for relationship between race and regionfaisalshafiq1Încă nu există evaluări

- ChiSquareTest LectureNotesDocument12 paginiChiSquareTest LectureNotesJam Knows RightÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9 0Document9 pagini9 0Wiwik RachmarwiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chi-Square Test Solutions for Problems on Age Group Deaths, Uniform Distribution, Eye & Hair Colors, and Machine BreakdownsDocument3 paginiChi-Square Test Solutions for Problems on Age Group Deaths, Uniform Distribution, Eye & Hair Colors, and Machine BreakdownsGoogle GamesÎncă nu există evaluări

- MT Chapter 18Document4 paginiMT Chapter 18Wilson LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Veterinary Journal: Jessica M.R. Cornelissen, Hans HopsterDocument7 paginiThe Veterinary Journal: Jessica M.R. Cornelissen, Hans HopsterVangelis PapachristosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Customer Perception On Frozen Food in Chennai: Malavikaa G, Sreeya.BDocument4 paginiCustomer Perception On Frozen Food in Chennai: Malavikaa G, Sreeya.BSiddharth Singh TomarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Genetics Lab Exercise 5 - Statistical Concepts and Tools-1Document5 paginiGenetics Lab Exercise 5 - Statistical Concepts and Tools-1Rianne MayugaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research MethodologyDocument31 paginiResearch Methodologyshahzad ahmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- How to analyze categorical data with statistical testsDocument39 paginiHow to analyze categorical data with statistical testsTi SIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit Chi-Square Test For Nominal Data: 20.0 ObjectivesDocument7 paginiUnit Chi-Square Test For Nominal Data: 20.0 ObjectivesNarayanan BhaskaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 7 - Statistical InferenceDocument62 paginiChapter 7 - Statistical InferenceRachel BrenerÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2263 Review Winter 2019 - UpdatedDocument9 pagini2263 Review Winter 2019 - UpdatedKhoi HuynhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statistics FoundationDocument26 paginiStatistics FoundationraymontesÎncă nu există evaluări