Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

(Articulo en Ingles) (2011) Una Asociación en Forma de U Entre La Intensidad de Uso de Internet y La Salud Del Adolescente

Încărcat de

Alejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

(Articulo en Ingles) (2011) Una Asociación en Forma de U Entre La Intensidad de Uso de Internet y La Salud Del Adolescente

Încărcat de

Alejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

DOI: 10.1542/peds.

2010-1235

; originally published online January 17, 2011; 2011;127;e330 Pediatrics

Richard E. Blanger, Christina Akre, Andr Berchtold and Pierre-Andr Michaud

Health

A U-Shaped Association Between Intensity of Internet Use and Adolescent

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/127/2/e330.full.html

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2011 by the American Academy

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned,

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

by guest on March 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from by guest on March 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

A U-Shaped Association Between Intensity of Internet

Use and Adolescent Health

WHATS KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Internet use has rapidly

become a commonplace activity, especially among adolescents.

Poor mental health and several somatic health problems are

associated with heavy Internet use by adolescents.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: Results of this study provide evidence

of a U-shaped relationship between intensity of Internet use and

poorer mental health of adolescents. Heavy Internet users were

also conrmed to be at increased risk for somatic health

problems in this nationally representative sample of adolescents.

abstract

OBJECTIVE: To examine the relationship between different Internet-

use intensities and adolescent mental and somatic health.

METHODS: Data were drawn from the 2002 Swiss Multicenter Adoles-

cent Survey on Health, a nationally representative survey of adoles-

cents aged 16 to 20 years in post-mandatory school. From a self-

administered anonymous questionnaire, 3906 adolescent boys and

3305 girls were categorized into 4 groups according to their intensity

of Internet use: heavy Internet users (HIUs; 2 hours/day), regular

Internet users (RIUs; several days per week and 2 hours/day), occa-

sional users (1 hour/week), and non-Internet users (NIUs; no use in

the previous month). Health factors examined were perceived health,

depression, overweight, headaches and back pain, and insufcient

sleep.

RESULTS: In controlled multivariate analysis, using RIUs as a refer-

ence, HIUs of both genders were more likely to report higher depres-

sive scores, whereas only male users were found at increased risk of

overweight and female users at increased risk of insufcient sleep.

Male NIUs and female NIUs and occasional users also were found at

increased risk of higher depressive scores. Back-pain complaints were

found predominantly among male NIUs.

CONCLUSIONS: Our study provides evidence of a U-shaped relation-

ship between intensity of Internet use and poorer mental health of

adolescents. In addition, HIUs were conrmed at increased risk for

somatic health problems. Thus, health professionals should be on the

alert when caring for adolescents who report either heavy Internet use

or very little/none. Also, they should consider regular Internet use as a

normative behavior without major health consequence. Pediatrics

2011;127:e330e335

AUTHORS: Richard E. Blanger, MD, Christina Akre, MA,

Andr Berchtold, PhD, and Pierre-Andr Michaud, MD

Research Group on Adolescent Health, Institute of Social and

Preventive Medicine, University of Lausanne, Lausanne,

Switzerland

KEY WORDS

adolescent, Internet, mental health, obesity, survey

ABBREVIATIONS

HIUheavy Internet user

RIUregular Internet user

OIUoccasional Internet user

NIUnon-Internet user

SESsocioeconomic status

RRRrelative risk ratio

CIcondence interval

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2010-1235

doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1235

Accepted for publication Nov 2, 2010

Address correspondence to Pierre-Andr Michaud, MD,

Research Group on Adolescent Health, Institute of Social and

Preventive Medicine (IUMSP), 1066 Epalinges, Switzerland.

E-mail: pierre-andre.michaud@chuv.ch

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright 2011 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have

no nancial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

e330 BLANGER et al

by guest on March 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

From its beginnings as a new technol-

ogy in the 1990s, Internet use has rap-

idly become a commonplace activity,

especially among young people.

1

Ado-

lescents have adopted its use exten-

sively, integrating it into many aspects

of their daily life.

2,3

As in other coun-

tries,

35

the vast majority of 14- to 19-

year-olds in Switzerland have reported

using the Internet several times per

week.

6

The growing importance of the Inter-

net for adolescents has gradually led

health professionals to examine the

health implications associated with

this activity. Although recent, this liter-

ature has established a link between

both mental and somatic health prob-

lems and heavy Internet use by adoles-

cents. Anxiety disorders, depression,

and suicidal ideation are reported

among adolescent Internet addicts

and other problematic users,

79

as well

as, more generally, among heavy us-

ers.

10,11

Adolescents who spend a sig-

nicant amount of time online also are

known to experience frequently physi-

cal problems such as headaches and

musculoskeletal pain,

12,13

probably

linked with muscular contractures

and lack of muscle-mobilizing activi-

ties. Poorer sleep and reduced sleep-

ing time are problems more likely to be

reported by young heavy Internet us-

ers (HIUs)

12,14

who are often using In-

ternet late in the evening and night.

Above all, at a time when obesity prev-

alence is critical, some cross-sectional

and longitudinal studies have shown

increased BMI among adolescents who

spend long hours online daily

10,15,16

and,

thus, do not engage in physical activity.

All these studies have, however,

tended to focus only on heavy Internet

use, whereas fewhave on the potential

correlates of low or nonexistent Inter-

net use.

17

Most have also considered

gender only as a possible confounder

when analyzing Internet use and

health, assuming that adolescent boys

and girls interact similarly with the

Internet, which is a fact that remains

unveried.

The aim of this article, therefore, was

to examine the relationship that exists

between different intensities of Inter-

net use and both mental and somatic

health, using a nationally representa-

tive sample of adolescent boys and

girls. It was postulated that HIUs would

be at greater health risk in compari-

son to regular users, and that low In-

ternet users would be in good health.

METHODS

Data were drawn from the 2002 Swiss

Multicenter Adolescent Survey on

Health (SMASH02) database, a nation-

ally representative survey that in-

cludes 7548 adolescents in post

mandatory school aged 16 to 20 years.

In Switzerland, school attendance is

mandatory up to age 16. Afterward,

30% of adolescents enter high

school (these students are usually the

most academically gifted and com-

monly enter university after), whereas

60% begin vocational school (these

are apprentices who usually have 1 or

2 days of classes per week and spend

the rest of the week working in a com-

pany related to their eld of study). An-

other 10% do not engage in any ad-

ditional education or training. The

study was approved by the ethics com-

mittee of the University of Lausanne

School of Medicine. An anonymous

self-administered questionnaire cov-

ering a number of health issues and

behaviors was completed by adoles-

cents in their classrooms. A full de-

scription of the questionnaire and

sampling method has been published

elsewhere.

18

The analyses were based on a

weighted sample of 7211 subjects

(3305 girls and 3906 boys) who had an-

swered 3 categorical questions about

the intensity of their Internet use over

the previous 30 days. HIUs were de-

ned as those who reported being on-

line for 2 hours or more every day. Sim-

ilar cutoff points have been previously

used in other studies.

3,19,20

Because no

consensus exists in the literature re-

garding the denition of regular Inter-

net use, regular Internet users (RIUs)

were arbitrarily dened as those sub-

jects who use the Internet several days

per week but for 2 hours/day. Occa-

sional Internet users (OIUs) were de-

ned as those who use the Internet

once per week or less, and non

Internet users (NIUs) as those who had

not been online in the previous 30

days.

We selected the most salient health

variables related to Internet use, on

the basis of associations described in

the literature.

712,1416

Self-perceived

health (excellent, very good, good, me-

diocre, and poor) was further dichoto-

mized into good and poor (mediocre or

poor). Overweight status (85th per-

centile for BMI according to age and

gender

21

) was calculated by using self-

reported height and weight. Frequency

of headaches and back pain in the pre-

ceding year, using a 4-point scale, was

dichotomized into frequent (quite or

very frequent) and infrequent (never

or rarely), whereas sleep quantity was

self-reported as insufcient or suf-

cient (sufcient or too much). The

presence of depression was assessed

using the Depressive Tendencies

Scale

22

(Cronbachs 0.89), which

ranges from 1 (not depressed at all) to

4 (very depressed).

Because of their potential inuence on

the presence of health problems, sev-

eral personal characteristics of partic-

ipants (age, academic track [appren-

tice versus student], socioeconomic

status [SES], the presence of a chronic

condition, and the amount of physical

activity) were used as adjusting vari-

ables in the multivariate analyses. The

level of education of both parents was

combined and used as a proxy mea-

ARTICLES

PEDIATRICS Volume 127, Number 2, February 2011 e331

by guest on March 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

sure of SES with 2 categories dened:

low (both parents with a low level of

education, dened as mandatory

schooling or less) and high (at least 1

parent with higher education). A

chronic condition was dened as a dis-

ease or condition that lasted for 6

months and required continuous med-

ical care. A similar denition was used

to characterize disability (6 months of

limited body function). Physical activity

was assessed through weekly partici-

pation in an extramural sport (further

dichotomized as more than once per

week and once per week or less) be-

cause it has been shown previously to

affect positively both physical and

mental health.

23

All analyses were performed sepa-

rately according to gender. Bivariate

analyses were used to determine dif-

ferences existing between the 4

groups regarding personal character-

istics and health status. Analysis of

variance was used for continuous vari-

ables and a

2

test for categorical

ones. We performed multinomial re-

gressions, controlling for all personal

characteristics and comparing groups

on all health factors concurrently be-

cause they may inuence each other.

RIUs were chosen as the reference

group for comparison because it was

hypothesized that they would repre-

sent the current norm of Internet use

by adolescents. Results are shown as

relative risk ratios (RRRs) with 95%

condence intervals (CIs). The analy-

ses were performed with Stata 10.1

(Stata Corp, College Station, TX), which

allows for computing coefcient esti-

mates and variances that take into ac-

count the sampling weights, cluster-

ing, and stratication procedure.

RESULTS

Among male adolescents, 7.3% were

identied as HIUs, whereas the vast

majority were either RIUs (44.9%) or

OIUs (31.4%). One in 8 male adoles-

cents (16.4%) reported not having

used the Internet during the month

preceding the survey. At the bivariate

level, as seen in Table 1, the 4 groups

differed regarding age, academic

track, SES, and physical activity. Over-

all, HIUs were the youngest (mean age:

18 years). Compared with both RIUs

and HIUs, very few NIUs (3.6%) re-

ported being students. NIUs reported a

lower SES more frequently. In multi-

variate analysis (Table 2), male HIUs

were more likely than RIUs to be over-

weight (RRR: 1.78 [95% CI: 1.072.95])

and to report higher depressive

scores (RRR: 1.36 [95% CI: 1.011.81]).

At the other extreme, NIUs were more

prone to report frequent back pain

(RRR: 1.87 [95% CI: 1.262.79]) and

higher depressive scores (RRR: 1.31

[95% CI: 1.021.67]).

In comparison with male adolescents,

fewer female adolescents were HIUs

(2.2%). The proportion of RIUs (41.5%)

and OIUs (39.8%) among female ado-

lescents was quite similar. One in 8 fe-

male adolescents reported no use of

the Internet in the month preceding

the survey. At the bivariate level, as

seen in Table 3, all groups showed dif-

ferences in age, academic track, and

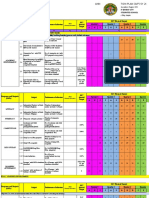

TABLE 1 Characteristics and Health Status of Adolescent Boys According to the Intensity of Their

Internet Use

NIUs

(N 642),

n (%)

OIUs

(N 1225),

n (%)

RIUs

(N 1752),

n (%)

HIUs

(N 286),

n (%)

P

Characteristics

Mean age (SE), y 18.23 (0.08) 17.98 (0.04) 17.86 (0.07) 17.85 (0.09) .005

Students academic track 23 (3.6) 210 (17.1) 525 (30.0) 81 (28.3) .001

Low SES 97 (16.1) 116 (10.0) 148 (8.7) 21 (7.3) .001

Chronic health conditions 68 (10.9) 110 (9.3) 190 (11.0) 24 (8.5) .670

Sport played more than once

per week

319 (51.2) 739 (61.1) 1085 (62.6) 160 (56.7) .010

Health status

Perceived poor health 56 (8.8) 72 (5.9) 72 (4.1) 27 (9.6) .016

Overweight 110 (17.8) 170 (14.4) 200 (11.8) 51 (18.0) .040

Back pain often 231 (36.5) 270 (22.2) 377 (21.6) 66 (23.0) .001

Headaches often 138 (21.6) 197 (16.2) 245 (14.0) 42 (14.9) .011

Sleep quantity insufcient 239 (38.4) 452 (37.3) 654 (37.8) 118 (42.0) .791

Mean depressive scale (SE) 1.72 (0.04) 1.56 (0.02) 1.51 (0.02) 1.70 (0.06) .001

TABLE 2 Multivariate Analysis of Health Problems According to Intensity of Internet Use, According

to Gender

NIUs, RRR

(95% CI)

OIUs, RRR

(95% CI)

HIUs, RRR

(95% CI)

Boys

Perceived poor health 1.21 (0.562.60) 1.28 (0.792.07) 2.11 (0.934.76)

Overweight 1.38 (0.912.07) 1.25 (0.931.70) 1.78 (1.072.95)

Back pain very often 1.87 (1.262.79) 0.92 (0.661.28) 0.98 (0.631.53)

Headaches very often 1.26 (0.821.96) 1.22 (0.911.65) 0.92 (0.581.47)

Sleep quantity insufcient 0.79 (0.551.13) 1.03 (0.801.33) 1.16 (0.811.68)

Depressive scale 1.31 (1.021.67) 1.03 (0.861.24) 1.36 (1.011.81)

Girls

Perceived poor health 0.94 (0.541.63) 0.86 (0.581.28) 0.85 (0.352.05)

Overweight 1.19 (0.344.14) 1.00 (0.541.83) 1.03 (0.392.67)

Back pain very often 1.06 (0.691.63) 0.96 (0.681.35) 0.88 (0.461.67)

Headaches very often 0.85 (0.611.20) 1.14 (0.901.46) 1.51 (0.822.77)

Sleep quantity insufcient 0.74 (0.531.04) 0.96 (0.751.23) 1.91 (1.073.42)

Depressive scale 1.46 (1.141.87) 1.24 (1.061.44) 1.86 (1.302.66)

Gender-specic multinomial regressions were controlled for age, academic track, SES, chronic condition, and physical

activity; RIUs served as a reference.

e332 BLANGER et al

by guest on March 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

presence of a chronic condition. On

multivariate analysis (Table 2), female

HIUs were more likely than RIUs to re-

port insufcient sleep (RRR: 1.91) and

higher depressive scores (RRR: 1.86).

In addition, OIUs and NIUs also re-

ported higher depressive scores (RRR:

1.24 [95% CI: 1.061.44] and RRR: 1.46

[95% CI: 1.141.87], respectively).

DISCUSSION

Our study provides evidence of a

U-shaped relationship between inten-

sity of Internet use and poorer mental

health of adolescents, as depicted

by self-reported depression scores

within a large nationally representa-

tive sample of subjects aged 16 to 20

years. In addition, the results conrm

HIUs to be at increased risk for so-

matic health problems, being associ-

ated with insufcient sleep among

female adolescents and excessive

weight among male adolescents. The

data regarding depression lend addi-

tional support to previous studies that

have focused on the mental health of

adolescents who are HIUs.

711

Less ex-

pected is the nding that adolescents

who reported lower Internet use (oc-

casional or no use at all) seem at

greater risk of depressive symptoms.

Such ndings underline the impor-

tance of distinguishing regular from

both low and heavy Internet use when

analyzing the presence of potential

health problems.

Similar nonlinear associations be-

tween mental health and at-risk behav-

iors have been reported among ado-

lescents. Vanheusden et al

24

found a

U-shaped association between alcohol

consumption and internalizing prob-

lems, as well as a J-shaped association

between alcohol use and aggressive

behavior. They concluded that both

nondrinkers and excessive drinkers

differed from low-level drinkers in risk

factors for poor mental health. Simi-

larly, ODonnell et al

25

found a U-shaped

association between alcohol consump-

tion and depressive symptoms in a

sample of young people from several

Western countries and a variety of cul-

tural backgrounds. Some years ago,

our research group also found a U-

shaped association between cannabis

use and social skills and physical activ-

ity.

26

Although such association with

substance use has recently been chal-

lenged,

27

as far as Internet use is con-

cerned, one can hypothesize that

young people who do not use the Inter-

net are in fact somehow outside the

cultural environment of their peers.

Thus, nonuse of the Internet is proba-

bly not linked to lack of access to a

computer (we controlled for the socio-

economic status of our subjects) but

more to those who do not engage in

social online activities with their

peers, because adolescents mostly

use the Internet as a way to stay con-

nected with their friends.

28

In other

words, although it is impossible with

transversal data to assess the direc-

tion of the relationship we found, we

can hypothesize that adolescents who

use the Internet at lower levels avoid

using it not because of their lack of

access, but from their isolation with

additional depressive symptoms. This

hypothesis is supported by a recent

prospective study reporting that de-

pression was present before Internet

addiction among a subset of adoles-

cents in Taiwan.

8

Regarding somatic health, female HIUs

reported insufcient sleep in a higher

proportion. Some authors mention

that adolescent sleep may have de-

creased in the last decades partly be-

cause of the use of new technologies

29

and that sleep problems among them

are linked to delayed bedtime hours

and disturbed sleep modes.

30

Social

live interactions are among the favor-

ite online activities of female adoles-

cents, regardless of their health condi-

tion,

31,32

which may explain why we

found an association among girls only.

Most evidence fromthe literature links

heavy Internet use to obesity.

15,16

Our

multivariate analysis leads to similar

ndings, but only among male adoles-

cents. Overweight and obesity prob-

lems are lower among female adoles-

cents than among male adolescents

living in Switzerland

33

which may have

prevented us from nding a link be-

tween weight problems and Internet

use among female adolescents. In

turn, male NIUs were found to be at

increased risk of frequent back pain.

Because the vast majority of male NIUs

in our sample were in apprentice-

ships, 1 possible explanation for this

TABLE 3 Characteristics and Health Status of Adolescent Girls According to the Intensity of Their

Internet Use

NIUs

(N 549),

n (%)

OIUs

(N 1314),

n (%)

RIUs

(N 1370),

n (%)

HIUs

(N 73),

n (%)

P

Characteristics

Mean age (SE), y 18.06 (0.08) 17.82 (0.04) 17.82 (0.05) 17.52 (0.14) .007

Students academic track 79 (14.5) 468 (35.6) 654 (47.7) 25 (34.4) .001

Low SES 80 (15.3) 142 (11.2) 105 (8.1) 8 (12.1) .080

Chronic health conditions 28 (5.3) 132 (10.3) 122 (9.1) 15 (20.9) .001

Sport played more than once

per week

196 (36.6) 470 (36.1) 595 (43.9) 34 (46.9) .062

Health status

Perceived poor health 33 (6.1) 84 (6.4) 71 (5.2) 7 (9.0) .041

Overweight 54 (10.6) 111 (8.8) 102 (7.6) 8 (10.8) .716

Back pain often 167 (36.4) 467 (35.7) 454 (33.2) 27 (37.5) .723

Headaches often 192 (35.2) 515 (39.5) 493 (36.2) 37 (50.8) .212

Sleep quantity insufcient 165 (30.7) 482 (37.3) 471 (34.8) 43 (58.6) .597

Mean depressive scale (SE) 1.88 (0.06) 1.87 (0.02) 1.75 (0.03) 2.16 (0.10) .001

ARTICLES

PEDIATRICS Volume 127, Number 2, February 2011 e333

by guest on March 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

nding may be that they have more

physical workloads than their peers

who are still in high school. We could

have expected such back pain to be

present among HIUs, but Hakala et al

13

have reported that adolescents need

to use the Internet at least 42 hours/

week to be at risk of back pain, an

amount of Internet use which probably

concerns only a minority of our group.

The major strength of our study is that

it is based on a nationally representa-

tive sample of adolescents. However,

some limitations must be addressed.

Adolescents not attending post

mandatory school were not included in

our study, which can limit the general-

ization of the results. Also, the nature

and total amount of time dedicated to

specic online activities were not as-

sessed, which partly limits the inter-

pretation of our results. The gathering

of our data dates to 2002: since then,

because of the evolution of multimedia

technologies, access to Internet has

been made easier (eg, cell phones or

electronic diaries), and the total time

spent online may have increased; how-

ever, an increase in the amount of total

time spent online should not have al-

tered the nature of the associations

that we found.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study, fromwhich a U-shaped rela-

tionship between intensity of Internet

use and depressive symptoms is de-

scribed, builds to some extent on a re-

cent study in which moderate use of

the Internet is shown to be associated

with a more positive academic orienta-

tion than are nonuse or high levels of

use.

17

The potential positive effects of a

moderate use of the Internet have pre-

viously been stressed in a position ar-

ticle of the Canadian Paediatric Soci-

ety.

34

It should be kept in mind,

however, that the effect of Internet use

on health is linked to not only the

amount of time spent, but also the

nature of these activities and the ob-

jectives followed by the young users.

35

As many parents currently expect ad-

vice fromhealth professionals on what

can be considered as a safe use of the

Internet, this article provides some ev-

idence that using the Internet several

days per week to 2 hours/day has

become a normative behavior during

adolescence. Health care providers

should thus be alerted both when car-

ing for adolescents who do not use the

Internet or use it rarely, as well as for

those who are online several hours

(2 hours) daily. For many years,

physicians and nurses who care for

adolescents have used the so-called

HEADSSS (home, education, activities,

drugs, sexuality, suicide, safety) acro-

nym to review the lifestyles of adoles-

cents.

36

This article stresses the im-

portance of adding routine questions

on Internet use to the list of items

to review when caring for young

people.

37,38

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The 2002 Swiss Multicenter Adolescent

Survey on Health was conducted with

the nancial support of Swiss Federal

Ofce of Public Health contracts

00.001721 to 2.24.02.-81 and the partic-

ipating cantons. Part of Dr Blangers

contribution was possible through

scholarships fromthe McLaughlin pro-

gram (Faculty of Medicine, Universit

Laval, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada),

the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de

Qubec and its foundation (Quebec

City), and the Royal College of Physi-

cians and Surgeons of Canada (Ot-

tawa, Ontario, Canada).

The survey was run within a multi-

center multidisciplinary group from

the Institute of Social and Preventive

Medicine in Lausanne (Vronique Ad-

dor, Chantal Diserens, Andr Jeannin,

Guy van Melle, Pierre-Andr Michaud,

Franoise Narring, Joan-Carles Suris),

the Institute for Psychology, Psychol-

ogy of Development and Developmen-

tal Disorders, University of Bern

(Franoise Alsaker, Andrea Btikofer,

Annemarie Tschumper), and the Sezi-

one Sanitaria, Dipartimento Della

Sanita` e Della Socialita` , Canton Ticino

(Laura Inderwildi Bonivento).

REFERENCES

1. Borzekowski DL. Adolescents use of the

Internet: a controversial, coming-of-age re-

source. Adolesc Med Clin. 2006;17(1):

205216

2. Paul B, Bryant JA. Adolescents and the inter-

net. Adolesc Med Clin. 2005;16(2):413426

3. Tsitsika A, Critselis E, Kormas G, et al. Inter-

net use and misuse: a multivariate regres-

sion analysis of the predictive factors of in-

ternet use among Greek adolescents. Eur J

Pediatr. 2009;168(6):655665

4. Bayraktar F, Gun Z. Incidence and corre-

lates of Internet usage among adolescents

in North Cyprus. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007;

10(2):191197

5. Sun P, Unger JB, Palmer PH, et al. Internet

accessibility and usage among urban ad-

olescents in southern California: implica-

tions for Web-based health research. Cy-

berpsychol Behav. 2005;8(5):441453

6. Indicateurs de la Socit de lInformation en

Suisse. Ofce Fdral de la Statistique OFS.

Available at: www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/fr/

index/themen/16/22/publ.Document.112725.

pdf. Accessed April 27, 2010

7. Kim K, Ryu E, Chon MY, et al. Internet addic-

tion in Korean adolescents and its relation

to depression and suicidal ideation: a ques-

tionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;

43(2):185192

8. Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen CS, Yeh YC, Yen CF. Pre-

dictive values of psychiatric symptoms for

internet addiction in adolescents: a 2-year

prospective study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc

Med. 2009;163(10):937943

9. Shapira NA, Goldsmith TD, Keck PE Jr, Kho-

sla UM, McElroy SL. Psychiatric features of

individuals with problematic internet use. J

Affect Disord. 2000;57(13):267272

10. Kim JH, Lau CH, Cheuk KK, Kan P, Hui HL,

Grifths SM. Brief report: predictors of

heavy Internet use and associations with

health-promoting and health risk behaviors

among Hong Kong university students. J

Adolesc. 2010;33(1):215220

e334 BLANGER et al

by guest on March 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

11. Ybarra ML, Alexander C, Mitchell KJ. Depres-

sive symptomatology, youth Internet use,

and online interactions: a national survey

[published correction appears in J Adolesc

Health. 2006;38(1):92]. J Adolesc Health.

2005;36(1):918

12. Chou C. Internet heavy use and addiction

among Taiwanese college students: an on-

line interview study. Cyberpsychol Behav.

2001;4(5):573585

13. Hakala PT, Rimpela AH, Saarni LA, Salminen

JJ. Frequent computer-related activities in-

crease the risk of neck-shoulder and low

back pain in adolescents. Eur J Public

Health. 2006;16(5):536541

14. Van den Bulck J. Television viewing, com-

puter game playing, and Internet use and

self-reported time to bed and time of bed in

secondary-school children. Sleep. 2004;

27(1):101104

15. Berkey CS, Rockett HR, Colditz GA. Weight

gain in older adolescent females: the inter-

net, sleep, coffee, and alcohol. J Pediatr.

2008;153(5):635639, 639.e1

16. Kautiainen S, Koivusilta L, Lintonen T, Vir-

tanen SM, Rimpela A. Use of information and

communication technology and prevalence

of overweight and obesity among adoles-

cents. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005;29(8):925933

17. Willoughby T. A short-term longitudinal

study of Internet and computer game use by

adolescent boys and girls: prevalence, fre-

quency of use, and psychosocial predictors.

Dev Psychol. 2008;44(1):195204

18. Jeannin A, Narring F, Tschumper A, et al.

Self-reported health needs and use of pri-

mary health care services by adolescents

enrolled in post-mandatory schools or vo-

cational training programmes in Switzer-

land. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135(12):1118

19. Louacheni C, Plancke L, Israel M. Teenagers

screen-watching habits in their leisure

time: use and misuse of the internet, play

stations and television. Psychotropes. 2007;

13:34

20. Meerkerk GJ, Van den Eijnden RJJM, Ver-

mulst AA, Garretsen HFL. The Compulsive In-

ternet Use Scale (CIUS): some psychometric

properties. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009;

12(1):16

21. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Es-

tablishing a standard denition for child

overweight and obesity worldwide: interna-

ti onal survey. BMJ. 2000; 320(7244):

12401243

22. Holsen I, Kraft P, Vitterso J. Stability in de-

pressed mood in adolescence: results from

a 6-year longitudinal panel study. J Youth

Adolesc. 2000;29:6178

23. Paluska SA, Schwenk TL. Physical activity

and mental health: current concepts.

Sports Med. 2000;29(3):16780

24. Vanheusden K, van Lenthe FJ, Mulder CL, et

al. Patterns of association between alcohol

consumption and internalizing and exter-

nalizing problems in young adults. J Stud

Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(1):4957

25. ODonnell K, Wardle J, Dantzer C, Steptoe A.

Alcohol consumption and symptoms of de-

pression in young adults from 20 countries.

J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67(6):83740

26. Suris JC, Akre C, Berchtold A, Jeannin A,

Michaud PA. Some go without a cigarette:

characteristics of cannabis users who have

never smoked tobacco. Arch Pediatr Ado-

lesc Med. 2007;161(11):10421047

27. Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Collins RL, Klein DJ.

Are drug experimenters better adjusted

than abstainers and users? A longitudinal

study of adolescent marijuana use. J Ado-

lesc Health. 2006;39(4):488494

28. Gross EF. Adolescent Internet use: what we

expect, what teens report. J Appl Dev Psy-

chol. 2004;25:633649

29. Calamaro CJ, Mason TB, Ratcliffe SJ. Adoles-

cents living the 24/7 lifestyle: effects of caf-

feine and technology on sleep duration and

daytime functioning. Pediatrics. 2009;

123(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/

cgi/content/full/123/6/e1005

30. Zimmerman FJ. Childrens Media Use and

Sleep Problems: Issues and Unanswered

Questions. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family

Foundation; 2008. Available at: www.kff.org/

entmedia/upload/7674.pdf. Accessed April

27, 2010

31. Lathouwers K, de MJ, Didden R. Access to

and use of Internet by adolescents who

have a physical disability: a comparative

study. Res Dev Disabil. 2009;30(4):702711

32. Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ, Wolak J, Finkelhor D.

Examining characteristics and associated

distress related to Internet harassment:

ndings from the Second Youth Internet

Safety Survey. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4). Avail-

able at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/

full/118/4/e1169

33. Mohler-Kuo M, Wydler H, Zellweger U,

Gutzwiller F. Differences in health status

and health behaviour among young Swiss

adults between 1993 and 2003. Swiss Med

Wkly. 2006;136(2930):464472

34. Impact of media use on children and youth.

Paediatr Child Health. 2003;8(5):301317

35. Tisseron S, Missonnier S, Stora M. LEnfant

au Risque du Virtuel. Paris, France: Dunod;

2006

36. Goldenring J, Rosen D. Getting into adoles-

cents HEADSS: an essential update. Con-

temp Pediatr. 2004;21(1):6490

37. Norris ML. HEADSS up: adolescents and the

Internet. Paediatr Child Health. 2007;12(3):

211216

38. Strasburger VC, Jordan AB, Donnerstein E.

Health effects of media on children and ad-

olescents. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):756767

ARTICLES

PEDIATRICS Volume 127, Number 2, February 2011 e335

by guest on March 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2010-1235

; originally published online January 17, 2011; 2011;127;e330 Pediatrics

Richard E. Blanger, Christina Akre, Andr Berchtold and Pierre-Andr Michaud

Health

A U-Shaped Association Between Intensity of Internet Use and Adolescent

Services

Updated Information &

tml

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/127/2/e330.full.h

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

tml#ref-list-1

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/127/2/e330.full.h

at:

This article cites 33 articles, 3 of which can be accessed free

Citations

tml#related-urls

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/127/2/e330.full.h

This article has been cited by 2 HighWire-hosted articles:

Subspecialty Collections

dia_sub

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/social_me

Social Media

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/media_sub

Media

_health:medicine_sub

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/adolescent

Adolescent Health/Medicine

the following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in

Permissions & Licensing

ml

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xht

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

Reprints

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2011 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All

and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned, published,

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

by guest on March 17, 2014 pediatrics.aappublications.org Downloaded from

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- 15 Body Types & WeightDocument29 pagini15 Body Types & Weightapi-286702267Încă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- (Libribook - Com) Integrative Preventive Medicine 1st EditionDocument582 pagini(Libribook - Com) Integrative Preventive Medicine 1st EditionDaoud Issa100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Full Plate Diet BookDocument164 paginiFull Plate Diet BookScarlettNyx100% (4)

- 35 Ielts Band 9 Sample EssaysDocument34 pagini35 Ielts Band 9 Sample EssaysQuỳnh Mai50% (2)

- How To Calculate Your Leangains MacrosDocument5 paginiHow To Calculate Your Leangains MacrosSofia WilliamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Get Ielts Band 9 in Writing Task 1 Data Charts and GraphsDocument11 paginiGet Ielts Band 9 in Writing Task 1 Data Charts and GraphsnayonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disadvantages of TelevisionDocument7 paginiDisadvantages of TelevisionSuvendran MorganasundramÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Artículo Ingles) (2013) La Relación Entre El Uso de Internet, El Estrés Acumulativo y Intimidad Matrimonial Entre Parejas Casadas Coreanos en Los Estados UnidosDocument132 pagini(Artículo Ingles) (2013) La Relación Entre El Uso de Internet, El Estrés Acumulativo y Intimidad Matrimonial Entre Parejas Casadas Coreanos en Los Estados UnidosAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo en Ingles) Valkenburg, P. M. y Peter, J. (2009) - Consecuencias Sociales de La Internet para Los AdolescentesDocument6 pagini(Articulo en Ingles) Valkenburg, P. M. y Peter, J. (2009) - Consecuencias Sociales de La Internet para Los AdolescentesAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo Ingles) (2013) La Relación Entre Las Redes Sociales de Internet, La Ansiedad Social, La Autoestima, El Narcisismo, y La Igualdad de Sexos Entre Los Estudiantes UniversitariosDocument83 pagini(Articulo Ingles) (2013) La Relación Entre Las Redes Sociales de Internet, La Ansiedad Social, La Autoestima, El Narcisismo, y La Igualdad de Sexos Entre Los Estudiantes UniversitariosAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo Ingles) (2013) El Uso de Internet y La Relación Entre Los Trastornos de Ansiedad, La Automedicación, El Neuroticismo, y La Búsqueda de Sensaciones (DSM-5)Document131 pagini(Articulo Ingles) (2013) El Uso de Internet y La Relación Entre Los Trastornos de Ansiedad, La Automedicación, El Neuroticismo, y La Búsqueda de Sensaciones (DSM-5)Alejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo en Ingles) (2013) Validación Del Cuestionario de Las Experiencias de Internet y Las Redes Sociales en Adolescente EspañolesDocument10 pagini(Articulo en Ingles) (2013) Validación Del Cuestionario de Las Experiencias de Internet y Las Redes Sociales en Adolescente EspañolesAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Behavior Related To Use of The Internet, Mobile Telephones, Compulsive Shopping and Gambling Among University StudentsDocument11 paginiAnalysis of Behavior Related To Use of The Internet, Mobile Telephones, Compulsive Shopping and Gambling Among University StudentsJose Bryan GonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo Ingles) (2012) Desarrollo de Una Escla para La Adiccion A FacebookDocument17 pagini(Articulo Ingles) (2012) Desarrollo de Una Escla para La Adiccion A FacebookAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo Ingles) (2012) La Relación Entre La Autorregulación, El Uso de Internet, y El Rendimiento Académico en Un Curso de Alfabetización InformáticaDocument130 pagini(Articulo Ingles) (2012) La Relación Entre La Autorregulación, El Uso de Internet, y El Rendimiento Académico en Un Curso de Alfabetización InformáticaAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo Ingles) (2009) - La Prevalencia de La Adicción A La Computadora y La Internet Entre AdolescentesDocument13 pagini(Articulo Ingles) (2009) - La Prevalencia de La Adicción A La Computadora y La Internet Entre AdolescentesAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo en Ingles) Wanajak, K. (2011) - El Uso de Internet y Su Impacto en Los Estudiantes de Escuelas Secundarias en ChiangDocument163 pagini(Articulo en Ingles) Wanajak, K. (2011) - El Uso de Internet y Su Impacto en Los Estudiantes de Escuelas Secundarias en ChiangAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo Ingles) (2002) La Relación Entre El Uso de La Internet y El Desarrollo Social en La AdolescenciaDocument78 pagini(Articulo Ingles) (2002) La Relación Entre El Uso de La Internet y El Desarrollo Social en La AdolescenciaAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Three-Factor Model of Internet Addiction: The Development of The Problematic Internet Use QuestionnaireDocument12 paginiThe Three-Factor Model of Internet Addiction: The Development of The Problematic Internet Use QuestionnaireAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo en Ingles) (2014) Efecto Del Uso Patológico de Internet en La Salud Mental Del AdolescenteDocument6 pagini(Articulo en Ingles) (2014) Efecto Del Uso Patológico de Internet en La Salud Mental Del AdolescenteAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo en Ingles) (2013) Validación Del Cuestionario de Las Experiencias de Internet y Las Redes Sociales en Adolescente EspañolesDocument10 pagini(Articulo en Ingles) (2013) Validación Del Cuestionario de Las Experiencias de Internet y Las Redes Sociales en Adolescente EspañolesAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo en Ingles) (2009) - El Riesgo Factores de Adicción A Internet. Una Encuesta Realizada A Estudiantes de Primer Año de La UniversidadDocument6 pagini(Articulo en Ingles) (2009) - El Riesgo Factores de Adicción A Internet. Una Encuesta Realizada A Estudiantes de Primer Año de La UniversidadAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo en Ingles) (2011) El Uso de Internet Problemática en Los Estudiantes Universitarios de Los Estados Unidos. Un Estudio PilotoDocument6 pagini(Articulo en Ingles) (2011) El Uso de Internet Problemática en Los Estudiantes Universitarios de Los Estados Unidos. Un Estudio PilotoAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo en Español) (2014) El Modelo de Los Cinco Grandes Factores de Pesonalidad y El Uso Problematico de Internet en Jovenes ColombianosDocument8 pagini(Articulo en Español) (2014) El Modelo de Los Cinco Grandes Factores de Pesonalidad y El Uso Problematico de Internet en Jovenes ColombianosAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo en Ingles) (2009) - El Riesgo Factores de Adicción A Internet. Una Encuesta Realizada A Estudiantes de Primer Año de La UniversidadDocument6 pagini(Articulo en Ingles) (2009) - El Riesgo Factores de Adicción A Internet. Una Encuesta Realizada A Estudiantes de Primer Año de La UniversidadAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo Ingles) (2013) El Uso de Internet y La Relación Entre Los Trastornos de Ansiedad, La Automedicación, El Neuroticismo, y La Búsqueda de Sensaciones (DSM-5)Document131 pagini(Articulo Ingles) (2013) El Uso de Internet y La Relación Entre Los Trastornos de Ansiedad, La Automedicación, El Neuroticismo, y La Búsqueda de Sensaciones (DSM-5)Alejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Articulo en Ingles) (2008) Efectos Positivos Del Uso de InternetDocument6 pagini(Articulo en Ingles) (2008) Efectos Positivos Del Uso de InternetAlejandro Felix Vazquez MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Đáp án cơ bản Test 3Document9 paginiĐáp án cơ bản Test 3Le TrinhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing Care Plan: Assessment Diagnosis Planning Interventions Rationale EvaluationDocument11 paginiNursing Care Plan: Assessment Diagnosis Planning Interventions Rationale EvaluationDa NicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health EpoDocument4 paginiHealth Epoapi-239325503Încă nu există evaluări

- Acupuncture and Weight Loss Combination PointsDocument7 paginiAcupuncture and Weight Loss Combination PointsFernândo SílvváÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutritional CounsellingDocument7 paginiNutritional CounsellingshilpasheetalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Policy Brief Food Advertising To ChildrenDocument4 paginiPolicy Brief Food Advertising To Childrenapi-267120287Încă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To The Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement StrategyDocument36 paginiIntroduction To The Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement StrategyAngelica Dalit Mendoza100% (1)

- Sreeya DAS - Satirical EssayDocument4 paginiSreeya DAS - Satirical EssaySreeyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Healthy Sleep: Your Guide ToDocument4 paginiHealthy Sleep: Your Guide ToJosé Luis HerreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- PE 11 TG v3 Final EdittedDocument87 paginiPE 11 TG v3 Final EdittedMark HingcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11 Effects of Sleep Deprivation On Your BodyDocument1 pagină11 Effects of Sleep Deprivation On Your Bodydayna mooreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practical ResearchDocument8 paginiPractical ResearchRomar CambaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wilson 2018Document6 paginiWilson 2018rulas workÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cassin 2013Document15 paginiCassin 2013Roberto Cabrera TorresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Police Shift Work Linked to Health RisksDocument64 paginiPolice Shift Work Linked to Health RisksvilladoloresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management of Obesity: Improvement of Health-Care Training and Systems For Prevention and CareDocument13 paginiManagement of Obesity: Improvement of Health-Care Training and Systems For Prevention and CareCarola CuervoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aip-Mtpa-Smea 2017-2018Document27 paginiAip-Mtpa-Smea 2017-2018ISABEL GASESÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lab-Ncm 105-Learn Mat Topic 1 WC WL Ob 2022-2023 1st SemDocument6 paginiLab-Ncm 105-Learn Mat Topic 1 WC WL Ob 2022-2023 1st SemDobby AsahiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Omron Scale HBF 400Document24 paginiOmron Scale HBF 400Lucy Fernanda MillanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 3 Yoga and LifestyleDocument14 paginiChapter 3 Yoga and LifestyleSakshamÎncă nu există evaluări

- DJ Hanley SR PaperDocument10 paginiDJ Hanley SR Paperapi-671021491Încă nu există evaluări

- Visitacion Act 1 Tdee Stats ReportDocument3 paginiVisitacion Act 1 Tdee Stats ReportHannah VisitacionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dual Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry Body Composition Reference Values From NhanesDocument9 paginiDual Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry Body Composition Reference Values From NhanesJhonnyAndresBonillaHenaoÎncă nu există evaluări