Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Devadula - Sustainable Technology and Human Behavior

Încărcat de

ISSSTNetwork0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

46 vizualizări7 paginiProblems of unsustainability are those of requirements of various stakeholders (humans) not being met or insufficiently met. This article juxtaposes Maslow's hierarchy with models of design ability and levels of leverage for systemic intervention. The journey of the designer in every individual from 'communicating less of more' to what can be called, 'technological adulthood', is claimed as the required transition to sustainability.

Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentProblems of unsustainability are those of requirements of various stakeholders (humans) not being met or insufficiently met. This article juxtaposes Maslow's hierarchy with models of design ability and levels of leverage for systemic intervention. The journey of the designer in every individual from 'communicating less of more' to what can be called, 'technological adulthood', is claimed as the required transition to sustainability.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

46 vizualizări7 paginiDevadula - Sustainable Technology and Human Behavior

Încărcat de

ISSSTNetworkProblems of unsustainability are those of requirements of various stakeholders (humans) not being met or insufficiently met. This article juxtaposes Maslow's hierarchy with models of design ability and levels of leverage for systemic intervention. The journey of the designer in every individual from 'communicating less of more' to what can be called, 'technological adulthood', is claimed as the required transition to sustainability.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 7

Proceedings of the International Symposium on

Sustainable Systems and Technologies, v2 (2014)

Understanding Sustainable Technology and Human Behaviour:

Adolescence to Adulthood!

Suman Devadula, Indian Institute of Science, devadula@cpdm.iisc.ernet.in

Amaresh Chakrabarti, Indian Institute of Science, ac123@cpdm.iisc.ernet.in

Abstract. Understanding the interactions between technology and human behavior continues to

be dominated by the tool-impact view under which only impact assessments can only be done

post facto with a considerable degree of uncertainty. The presumption that these assessments

take technology as a fact independent of humans rather than as artifacts which humans design

and build is invalidated in the view of the requirement calling for approaches that consider

humans and technology as co-constituting each other in an ongoing process. Problems of

unsustainability are those of requirements of various stakeholders (humans) not being met or

insufficiently met. A profile of these requirements is generally based on those arising out of

human needs that are hierarchical according to Maslow. Design as a process of arriving at

specifications, which if implemented, meet requirements, and thereby, satisfy human needs, is

analogous to communication. This article juxtaposes Maslows hierarchy with models of design

ability and levels of leverage for systemic intervention so as to compare the requirements for

communication and hence to design technological interventions appropriate for meeting

requirements of sustainability eventually. The journey of the designer in every individual from

communicating less of more to communicating more of less, as the individual ages designing

for meeting needs up the hierarchy, is claimed as the required transition to sustainability, from

technological adolescence, to what can be called, technological adulthood.

Introduction. Though stated as grand challenges of sustainability science (Clark WC, 2003),

questions like, What should be the human use of earth? are praxeological and answering

these with rigor and repeatability of method is still in its infancy (Gilberto, 2004). It is arguable

whether such methods can at all answer normative questions involving judgment about the

contingent. However, phenomenological approaches can be suitable candidates to address

such questions. Motivated primarily by the consequences of using technology to earths

habitability, current opinion of how technology is related with human behavior can be largely

categorized under the tool-impact view (Postman, 1993) (Verbeek & Kockelkoren, 1998). This

approach considers technology as a given/fact already and hence falls short in answering

questions like, How did we end-up with the technologies we have now?, How could we not

have developed better ones then?, etc. Participating scientists of the fifth IPCC report are of the

opinion that we can no longer claim ignorance of the consequences of our actions (Dechert,

2014). This necessarily requires steering focus away from post facto impact assessments of

Proceedings of the International Symposium on Sustainable Systems and Technologies (ISSN 2329-9169) is

published annually by the Sustainable Conoscente Network. Melissa Bilec and J un-Ki Choi, co-editors.

ISSSTNetwork@gmail.com.

Copyright 2014 by Suman Devadula, Amaresh Chakrabarti Licensed under CC-BY 3.0.

Cite as: Understanding Sustainable Technology and Human Behaviour: Adolescence to Adulthood!

If applicable, page number will go here after aggregating all papers

Understanding Sustainable Technology and Human Behaviour: Adolescence to Adulthood!

Proc. ISSST, Name of Authors. Doi information v2 (2014)

If applicable, page number will go here after aggregating all papers

S.Devadula et al.

technology to understanding how technology and human behavior co-constitute each other in

an ongoing process[]. This brings the process of humans coming about with technology and

bringing design into question. Hence, this article situates the phenomenon of design central to

such co-constitution and attempts to understand it phenomenologically hoping to disclose the

technology/human interaction at an ontological level. Such phenomenological understanding of

world-hood is also the context of sustainability, as its stated concerns are frequently earth-scale

mentions of warming climates, depleting resources, acidifying oceans, retreating forest-covers

etc. However, originally, sustainability is anthropocentric and this requires understanding it as a

human ability before attributing it as humanitys ability. The article assumes the ability to design

to be this human ability.

In the context of global problems on earth foreboding collapse and the offer of promise for the

future of humanity, it is said that the quest for extraterrestrial intelligence is next to no other and

a single message from space will show that it is possible to live through technological

adolescence (Sagan, 1978). More recently, in the context of the promise ICT offers to

governance and public administration, its misuse and consequent mistrust may also be

considered an aspect of humanitys technological adolescence (Huffington, 2011). Scientists

and technologists alike were remorseful at the uses to which technology could be put to

(Einstein, 1954). Contrarily there are others too believing that science and technological

innovation is directed to solve particular problems it should however be detached from the

possible misuses it could be put to (Valiunas, 2006). A humanity knowing and following

developmental pathways that avoid technological disaster is considered to have reached

technological maturity or adulthood. Technicity, or the process of designing and developing

technology, is arguably the central philosophical question forgotten over since the Greeks

(Stiegler, 1998). Sustainability as a human ability, refers to the possibility and belief in

conducting ourselves in ways that avoid technological disasters and, more importantly, to steer

towards a desirable future.

Research objective. The objective of this research article is to understand how humans and

technology co-constitute each other interactively in design. This can progressively inform the

management of technology-led transitions to sustainable development at various levels as is

design situated in meeting hierarchical needs.

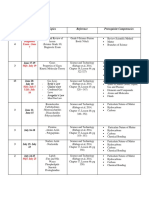

Method. The article is an interdisciplinary exploration of three models (pyramids in Figure1),

juxtaposing them temporally. Flanking the Maslows hierarchy of relative pre-potency of needs

(Maslow, 1943) are the progressive levels of design ability (Dorst, 2008) and the levels of

leverage for systemic intervention (Meadows, 1999) to the left and right respectively. Both the

If applicable, page number will go here after aggregating all papers

Understanding Sustainable Technology and Human Behaviour: Adolescence to Adulthood!

Figure 1: Communicative requirements for the design of systemic interventions for sustainability

(Note: The horizontal lines within any pyramid are used to indicate levels and do not mean the existence of clear

divisions between skill levels, needs or leverage points)

inveted pyramids increase in scope they effect upwards. Problems of unsustainability are those

of requirements of various stakeholders (humans) not being met or insufficiently met. A profile of

these requirements is generally based on those arising out of human needs that are hierarchical

according to Maslow. Designing is about improving situations and to know where to intervene in

a system to improve it, it is appropriate to know the state of satisfaction of various human needs.

The identification of these needs situates the necessary design abilities (left pyramid) required

to effect (systemic) change as necessary (right pyramid). Table1 is arranged correspondingly.

If applicable, page number will go here after aggregating all papers

S.Devadula et al.

Table1. Description of the various levels of models juxtaposed in Figure1

Discussion and Conclusion. The spine of the juxtaposition in Figure 1 Maslows model

reflects the rights basis of the concept of sustainability that humans should be enabled to lead a

full life i.e. are provided enough opportunity to realize their full potential. While the ability of

sustainability is the design ability to know how to affect change to meet ones own needs

progressively, opportunity is the access to learning required to acquire the design ability and the

access to means for implementation. Technology is the context in which individuals, who having

identified their needs and having been provided with opportunity, design and implement

solutions to satisfy needs. The question of technology being sustainable or not lies in the state

of distribution of people bereaved of opportunities as a result of which they are dependent on

If applicable, page number will go here after aggregating all papers

Understanding Sustainable Technology and Human Behaviour: Adolescence to Adulthood!

others who are more opportune. Hence ensuring that opportunity is accessible to all appropriate

to their situation of needs is the path towards making technology-led human development

sustainable. Inadequacies of such a system of situations can be further identified as systemic

problems requiring intervention at appropriate levels of leverage based on Figure1. Figure1 also

aids to situate the design skill required for controlling unsustainability.

Sustainability is the ability to meet our needs without compromising the ability of the future

generations to meet their own (Brundtland, 1987). Though mentioned as a collective ability it is

primarily an individual ability to act in a way that does not consume opportunities that afford

others, co-existing and to come, to act similarly. Action, as response to requirements, can be

voluntary or involuntary. When voluntary it can be attributed to the beings volition and when

involuntary it can be attributed to the self-organizing processes adapting to changing

environments. In the context of evolution of artifacts and context this can be compared with the

propositions of Petroski (Petroski, The Evolution of Useful Things) (Petroski, The Evolution of

Artifacts) and Schlossberg (Schlossberg, 1977) respectively. Such adaptation effects

populations through to the individuals constitution. Volition is a recently evolved ability in

comparison with evolved features. Volition, for this reason, can be an offshoot of the extremely

high interconnectedness of our constitution that the course of self-organization has resulted in

and continuing. In this sense volition might be privy of humans. Self-organization is considered

to be the character of all life, and thermodynamically, of all open systems. Entropy is the

exhaust of the evolution engine and consequently all involuntary activity of life increases the

disorderliness of the universe that provides for our larger cosmic being. The universe, taken as

an isolated system comprising open systems, is progressing towards increasing its

disorderliness, both through voluntary or involuntary action that is possible of its constituents. In

such a scenario of both avoidable and unavoidable activity increasing the rate at which

opportunities will be consumed, the prescription for sustainability as a human ability is to avoid

as much voluntary activity as possible so that more opportunity is afforded for the co-existing

and to come. As this should be the agenda of all humans and in a situation where such a

prescription may not be fathomable to all, our constructive discontent should be directed to

ensuring successful communication of this prescription to all. Beyond whatever that is

necessary for self-maintenance and self-replication, this alone should determine the direction for

all voluntary action. This is purposive action and hence meaningful. In a situation where

everyone understands this and behaves accordingly, contented acceptance replaces

constructive discontent. When the nature, variability and spontaneity of the processes of earth

shift the balance of opportunities, it is our responsibility to adjust between such constructive

discontent and contented acceptance to restore balance. With this basis of the argument, it is

appropriate to refer to our interventions as tackling unsustainability, in a Sisyphean sense,

which involves more time and effort rather than a vainglorious phrase of achieving

sustainability which is only momentary. Hence, sustainability as a human ability requires us to

be able to mutually inform ourselves successfully of purposive action; the particular purpose

being the affordance of purposive action in others. The more such a purpose is afforded in

people, the more such people afford similar affordances in others (Withagen, de Poel, Arajo, &

Pepping), thereby sustaining habitable and enlivening conditions, longer.

As the hierarchical Maslows needs are progressively satisfied the requirement for material to

meet needs decreases (though seeming to increase at the self-esteem needs temporarily). This

progression culminates in the individual using his own embodiment to self-actualize, be aware

of his/her worldview and transcend worldviews. In this condition the object of necessity and the

means are gradually drawn inwards from an otherwise outward emphasis on means to be acted

upon by the designing individual as a separate entity. This condition is synonymous with co-

constitution though it happens at all levels of designing to meet Maslows needs. On comparing

If applicable, page number will go here after aggregating all papers

S.Devadula et al.

the progressive levels of design expertise and Maslows hierarchy it is observable that the focus

on material objects of the nave through to the focus on extending domains of the visionary

indicates at an increasing trend of less and less material requirement. Eventually, on knowing

that the self is the means as well as the object of necessity the individual transcends this whole

process by design requiring minimal design and hence minimal material means any further. It

may be observed that the constructs dealt by the designer designing at this level are indeed

conceptual largely dealing with which individuals will be in a position to effect systemic change

with the maximum leverage. This is the condition wherein communicating more of less is

required progressing gradually from communicating less of more.

References.

Brundtland, H. (1987). Our Common Future. Oxford University Press.

Clark WC. (2003). Grand Challenges of Sustainability Science, William Clark, . International

Conference on Science and Technology for Sustainability 2003: Energy and

Sustainability Science (pp. 16-19). Tokyo: Science Council of J apan.

Dechert, S. (2014, March 31). UN authors: 'We can no longer plead ignorance' on climate

change. Retrieved April 10, 2014, from http://digitaljournal.com/news/environment/un-

authors-we-can-no-longer-plead-ignorance-on-climate-change/article/379030

Dorst, K. (2008). Design Research: a revolution waiting to happen. Design Studies, 29, 4-11.

Einstein, A. (1954). Ideas and Opinions. New York: Crown.

Gilberto, C. G. (2004). Sustainable Development: Epistemological Challenges to Science and

Technology. ECLAC, Santiago, Chile.

Huffington, A. (2011, J une 16). The Internet Grows up: Goodbye messy adolescence. Retrieved

April 30, 2014, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/arianna-huffington/the-internet-

grows-up-goo_b_878157.html

Maslow, A. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-396.

Retrieved from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm

Meadows, D. H. (1999). Leverage Points: Places to intervene in a System. Sustainability

Institute.

Petroski, H. (n.d.). The Evolution of Artifacts. American Scientist, pp. 416-420.

Petroski, H. (n.d.). The Evolution of Useful Things. New York: Random House.

Postman, N. (1993). Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology. New York: Alfred A

Knopf.

Sagan, C. (1978). The Quest for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. In C. Sagan, Cosmic Search (Vol.

1 No.2). Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved April 30, 2014, from

www.bigear.org/volno2/sagan.htm

Schlossberg, E. (1977). For my father. In J . Brockman, About Bateson. NY: Dutton.

Stiegler, B. (1998). Technics and Time, 1:The Fault of Epimetheus,. Stanford: Stanford

University Press.

Valiunas, A. (2006). The Agony of Atomic Genius. The New Atlantis: A Journal of Technology &

Society, 14, 85-104. Retrieved from http://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/the-

agony-of-atomic-genius

Verbeek, P.-P., & Kockelkoren, P. (1998). The Things That Matter. Design Issues, 14(3), 28-42.

Wiener, N. (1989). The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society. London: Free

Association Books.

Withagen, R., de Poel, H. J ., Arajo, D., & Pepping, G.-J . (n.d.). Affordances can invite

behaviour: Reconsidering the relationships between affordances and agency. New Ideas

in Psychology 30 (2012) 250258.

If applicable, page number will go here after aggregating all papers

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- GE 6103 - Living in The IT Era Finals Docx by LeonardDocument5 paginiGE 6103 - Living in The IT Era Finals Docx by LeonardChoe Yoek Soek100% (1)

- Adler - Social-Interest Adler PDFDocument178 paginiAdler - Social-Interest Adler PDFBóbita Babaklub100% (1)

- The Actor Network Theory (ANT)Document15 paginiThe Actor Network Theory (ANT)Ambar Sari Dewi100% (2)

- Chapter 26 Phylogeny and The Tree of LifeDocument41 paginiChapter 26 Phylogeny and The Tree of LifeSheerin Sulthana100% (1)

- Lesson 9 Human-Computer Interaction (Essentials of Nursing Informatics by Saba & McCormick)Document17 paginiLesson 9 Human-Computer Interaction (Essentials of Nursing Informatics by Saba & McCormick)michelle marquez0% (1)

- Didi Huberman Georges The Surviving Image Aby Warburg and Tylorian AnthropologyDocument11 paginiDidi Huberman Georges The Surviving Image Aby Warburg and Tylorian Anthropologymariquefigueroa80100% (1)

- Collins - Physical and Chemical Degradation of BatteriesDocument6 paginiCollins - Physical and Chemical Degradation of BatteriesISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cambridge University Press The British Society For The History of ScienceDocument30 paginiCambridge University Press The British Society For The History of ScienceAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Under The Plum Tree by Chung Fu. Marjorie GilesDocument204 paginiUnder The Plum Tree by Chung Fu. Marjorie GilesocarangoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Genetic Diversity - Checklist PDFDocument3 paginiGenetic Diversity - Checklist PDFZain KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- GE 7 Module 5Document11 paginiGE 7 Module 5Karl Merencillo MarahayÎncă nu există evaluări

- State of Science Evolving Perspectives On Human ErrorDocument25 paginiState of Science Evolving Perspectives On Human Errorencuesta.doctorado2023Încă nu există evaluări

- Tech Affordance Mate AgencDocument23 paginiTech Affordance Mate AgencI love ADÎncă nu există evaluări

- Computational-Thinking Pres 2014Document14 paginiComputational-Thinking Pres 2014Wong Weng SiongÎncă nu există evaluări

- When Means Become Ends: Technology Producing Values: Bjørn HofmannDocument12 paginiWhen Means Become Ends: Technology Producing Values: Bjørn HofmannAyat FikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design For A Common World: On Ethical Agency and Cognitive Justice Maja Van Der VeldenDocument11 paginiDesign For A Common World: On Ethical Agency and Cognitive Justice Maja Van Der VeldenOmega ZeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethical ImplicationsDocument4 paginiEthical Implicationspeeteem0052396Încă nu există evaluări

- Maslow PiramidDocument22 paginiMaslow PiramidPopete Mihail ValentinÎncă nu există evaluări

- PannabeckerDocument11 paginiPannabeckersilvia moschnerÎncă nu există evaluări

- ER2014 Keynote CR 3Document14 paginiER2014 Keynote CR 3quevengadiosyloveaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 12Document4 paginiChapter 12Subham JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technostress Measuring A New Threat To Well Being in Later LifeDocument9 paginiTechnostress Measuring A New Threat To Well Being in Later LifeAnnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dron Participatory Orchestration AISpreprintDocument41 paginiDron Participatory Orchestration AISpreprintAkhmada Khasby Ash ShidiqyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Phraseology Inspired by Douglas Adam's Book "Life, The Universe, and Everything"Document5 pagini1 Phraseology Inspired by Douglas Adam's Book "Life, The Universe, and Everything"HanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6827 26361 3 PBDocument31 pagini6827 26361 3 PBAuliya PutriÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9: When Technology and Humanity CrossDocument17 pagini9: When Technology and Humanity CrossUnknown TototÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Statement About Technology AdvancementDocument7 paginiThesis Statement About Technology Advancementafcmfuind100% (2)

- SssssDocument19 paginiSssssRyan's Digital Printing ServicesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Application of Case Studies to Engineering Management and Systems Engineering EducationDocument18 paginiApplication of Case Studies to Engineering Management and Systems Engineering EducationNeoly Fee CuberoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Translocal Empowerment in Transformative Social Innovation NetworksDocument24 paginiTranslocal Empowerment in Transformative Social Innovation NetworksAbdullah M. Al BlooshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tugas Kelompok Perenc PendDocument32 paginiTugas Kelompok Perenc PendEko WidodoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human Error: Human Error Refers To Something Having Been Done That Was "Not Intended by The Actor Not Desired by ADocument4 paginiHuman Error: Human Error Refers To Something Having Been Done That Was "Not Intended by The Actor Not Desired by Afroggoand decrewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit-I: Science & Technology StudyDocument39 paginiUnit-I: Science & Technology StudyNitin GroverÎncă nu există evaluări

- Japan Symposium 08Document40 paginiJapan Symposium 08Rene BreisÎncă nu există evaluări

- HCI Impact on Users in Higher EducationDocument12 paginiHCI Impact on Users in Higher EducationDennoh VegazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Int. J. Human-Computer Studies: Michael Liegl, Alexander Boden, Monika Büscher, Rachel Oliphant, Xaroula KerasidouDocument16 paginiInt. J. Human-Computer Studies: Michael Liegl, Alexander Boden, Monika Büscher, Rachel Oliphant, Xaroula KerasidouSYREÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nepal and The "Urban Resilience Utopia"Document15 paginiNepal and The "Urban Resilience Utopia"Dipak BudhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carsten-Technology and The Control SocietyDocument9 paginiCarsten-Technology and The Control SocietyBetzy torres zegarraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ge-6 Science, Technology, and Society 1 Semester, A.Y. 2023-2024 Code: A3 Deadline of Submission: November 28, 2023 - 12:00 NNDocument3 paginiGe-6 Science, Technology, and Society 1 Semester, A.Y. 2023-2024 Code: A3 Deadline of Submission: November 28, 2023 - 12:00 NNMark Anthony Cordova BarrogaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zara Cagolcol Assessment-4Document1 paginăZara Cagolcol Assessment-4zaracgxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technological Forecasting & Social Change 160 (2020) 120174Document15 paginiTechnological Forecasting & Social Change 160 (2020) 120174Danna GomezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Serendipity As!an!emerging Design Principle Of!the!infosphere: Challenges And!opportunities Reviglio 2019Document16 paginiSerendipity As!an!emerging Design Principle Of!the!infosphere: Challenges And!opportunities Reviglio 2019Miguel MoralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Materials and Sustainable Development - A White PaperDocument45 paginiMaterials and Sustainable Development - A White PaperluisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final PaperDocument9 paginiFinal PapercsufyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tech ControlDocument9 paginiTech ControlALEXANDER MORALESÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hopster - What Are Socially Disruptive TechnologiesDocument8 paginiHopster - What Are Socially Disruptive TechnologiesAnonymous DABLgkÎncă nu există evaluări

- El Factor Humano y Modelos TradicionalesDocument8 paginiEl Factor Humano y Modelos TradicionalesGokumana XDÎncă nu există evaluări

- MILLERAND & BOWKER - Metadata Standards. Trajectories and Enactment in The Life of An OntologyDocument17 paginiMILLERAND & BOWKER - Metadata Standards. Trajectories and Enactment in The Life of An OntologyCecilia SindonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Questioning Technological Impact on Pursuit of Meaningful LifeDocument11 paginiQuestioning Technological Impact on Pursuit of Meaningful Lifeimg_lombokÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technocratic Paradigm Reflective Answers ASORIANODocument2 paginiTechnocratic Paradigm Reflective Answers ASORIANOALEJANDRO SORIANOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swarts Info AgentsDocument30 paginiSwarts Info AgentsgpinqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ai 123Document26 paginiAi 123June AndrewÎncă nu există evaluări

- SG 8Document5 paginiSG 8Kissiw SisiwÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sts Module 1 6 Lecture Notes 3 7Document79 paginiSts Module 1 6 Lecture Notes 3 7Mckleen Jeff Onil ArocoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A3-Sts (Activity-Done)Document3 paginiA3-Sts (Activity-Done)Justin DecanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- IT and DevelopmentDocument5 paginiIT and DevelopmentjamesmulliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annotated BibliographyDocument5 paginiAnnotated Bibliographyapi-395413353Încă nu există evaluări

- Technological Forecasting & Social Change-1Document9 paginiTechnological Forecasting & Social Change-1Sirisha NÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Outline of Human Socioenvironmental CoevolutionDocument23 paginiAn Outline of Human Socioenvironmental CoevolutionJairo RacinesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Response Paper 6.1Document7 paginiResponse Paper 6.1Ntombizethu LubisiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Future Ethics: Risk, Care and Non-Reciprocal ResponsibilityDocument20 paginiFuture Ethics: Risk, Care and Non-Reciprocal ResponsibilityChris GrovesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coping Mechanisms of Academic Librarians in Davao CityDocument13 paginiCoping Mechanisms of Academic Librarians in Davao CityKim Valerie CalumnoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topic 6: Knowledge and Technology: Cultural ArtefactsDocument4 paginiTopic 6: Knowledge and Technology: Cultural ArtefactsElizaveta TemmoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Design Theory For Distributed Interactive Systems Alistair Sutcliffe Dept of Computation, UmistDocument4 paginiA Design Theory For Distributed Interactive Systems Alistair Sutcliffe Dept of Computation, UmistAshish SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- A3-Sts BarrogaDocument4 paginiA3-Sts BarrogaMark Anthony Cordova BarrogaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iwa Final Draft RealDocument10 paginiIwa Final Draft Realapi-670586475Încă nu există evaluări

- Zhang - LCA of Solid State Perovskite Solar CellsDocument12 paginiZhang - LCA of Solid State Perovskite Solar CellsISSSTNetwork100% (1)

- Dundar - Robust Optimization Evaluation of Relience On Locally Produced FoodsDocument9 paginiDundar - Robust Optimization Evaluation of Relience On Locally Produced FoodsISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abbasi - End of Life Considerations For Glucose BiosensorsDocument7 paginiAbbasi - End of Life Considerations For Glucose BiosensorsISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Farjadian - A Resilient Shared Control Architecture For Flight ControlDocument8 paginiFarjadian - A Resilient Shared Control Architecture For Flight ControlISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Collier - Value Chain For Next Generation Aviation BiofuelsDocument18 paginiCollier - Value Chain For Next Generation Aviation BiofuelsISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Berardy - Vulnerability in Food, Energy and Water Nexus in ArizonaDocument15 paginiBerardy - Vulnerability in Food, Energy and Water Nexus in ArizonaISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cao - Modeling of Adoption of High-Efficiency LightingDocument8 paginiCao - Modeling of Adoption of High-Efficiency LightingISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guschwan - Gamiformics: A Systems-Based Framework For Moral Learning Through GamesDocument6 paginiGuschwan - Gamiformics: A Systems-Based Framework For Moral Learning Through GamesISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hanes - Evaluating Oppotunities To Improve Material and Energy ImpactsDocument12 paginiHanes - Evaluating Oppotunities To Improve Material and Energy ImpactsISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kachumbron - Diary Reading of Grass Root Level InstitutionsDocument9 paginiKachumbron - Diary Reading of Grass Root Level InstitutionsISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kuczenski - Privacy Preserving Aggregation in LCADocument9 paginiKuczenski - Privacy Preserving Aggregation in LCAISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nelson - Literacy and Leadership Management Skills of Sustainable Product DesignersDocument11 paginiNelson - Literacy and Leadership Management Skills of Sustainable Product DesignersISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shi - Benefits of Individually Optimized Electric Vehicle Battery RangeDocument8 paginiShi - Benefits of Individually Optimized Electric Vehicle Battery RangeISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parker - Striving For Standards in SustainabilityDocument10 paginiParker - Striving For Standards in SustainabilityISSSTNetwork100% (1)

- Tu - Unknown PollutionDocument9 paginiTu - Unknown PollutionISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dev - Is There A Net Energy Saving by The Use of Task Offloading in Mobile Devices?Document10 paginiDev - Is There A Net Energy Saving by The Use of Task Offloading in Mobile Devices?ISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sweet - Learning Gardens: Sustainability Laboratories Growing High Performance BrainsDocument8 paginiSweet - Learning Gardens: Sustainability Laboratories Growing High Performance BrainsISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wang - Challenges in Validation of Sustainable Products and Services in The Green MarketplaceDocument8 paginiWang - Challenges in Validation of Sustainable Products and Services in The Green MarketplaceISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Campion - Integrating Environmental and Cost Assessments For Data Driven Decision-Making: A Roof Retrofit Case StudyDocument11 paginiCampion - Integrating Environmental and Cost Assessments For Data Driven Decision-Making: A Roof Retrofit Case StudyISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reyes-Sanchez - Beyond Just Light Bulbs: The Mitigation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in The Housing Sector in Mexico CityDocument14 paginiReyes-Sanchez - Beyond Just Light Bulbs: The Mitigation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in The Housing Sector in Mexico CityISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Al-Ghamdi - Comparative Study of Different Assessment Tools For Whole-Building LCA in Relation To Green Building Rating SystemsDocument8 paginiAl-Ghamdi - Comparative Study of Different Assessment Tools For Whole-Building LCA in Relation To Green Building Rating SystemsISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Krishnaswamy - Assessment of Information Adequacy of Testing Products For SustainabilityDocument7 paginiKrishnaswamy - Assessment of Information Adequacy of Testing Products For SustainabilityISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Momin - Role of Artificial Roughness in Solar Air HeatersDocument5 paginiMomin - Role of Artificial Roughness in Solar Air HeatersISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lee - Addressing Supply - and Demand-Side Heterogeneity and Uncertainty Factors in Transportation Life-Cycle Assessment: The Case of Refuse Truck ElectrificationDocument9 paginiLee - Addressing Supply - and Demand-Side Heterogeneity and Uncertainty Factors in Transportation Life-Cycle Assessment: The Case of Refuse Truck ElectrificationISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cirucci - Retrospective GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis: A Case Study of California Waste Transfer Station Siting DecisionsDocument15 paginiCirucci - Retrospective GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis: A Case Study of California Waste Transfer Station Siting DecisionsISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ruini - A Workplace Canteen Education Program To Promote Healthy Eating and Environmental Protection. Barilla's "Sì - Mediterraneo" ProjectDocument4 paginiRuini - A Workplace Canteen Education Program To Promote Healthy Eating and Environmental Protection. Barilla's "Sì - Mediterraneo" ProjectISSSTNetwork100% (1)

- Berardy - Life Cycle Assessment of Soy Protein IsolateDocument14 paginiBerardy - Life Cycle Assessment of Soy Protein IsolateISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Graphic Tools and LCA To Promote Sustainable Food Consumption: The Double Food and Environmental Pyramid of The Barilla Center For Food and NutritionDocument6 paginiGraphic Tools and LCA To Promote Sustainable Food Consumption: The Double Food and Environmental Pyramid of The Barilla Center For Food and NutritionISSSTNetworkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science (Reading For Meaning) - 1Document68 paginiScience (Reading For Meaning) - 1PeterÎncă nu există evaluări

- DNAfractalantenna 1Document8 paginiDNAfractalantenna 1Guilherme UnityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Letters Between EnemiesDocument188 paginiLetters Between EnemiesVishesh DewanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Keeling Et Al. 2005. TRENDS in Ecol. Evol. 20, 670-676. The Tree of EukaryotesDocument7 paginiKeeling Et Al. 2005. TRENDS in Ecol. Evol. 20, 670-676. The Tree of EukaryotesviniruralÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 7 Genetic AlgorithmsDocument18 paginiLecture 7 Genetic AlgorithmsjegosssÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crimso2 Theories of Crime CausationDocument52 paginiCrimso2 Theories of Crime CausationHaru YukiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evolution and Ecology of Plant VirusesDocument13 paginiEvolution and Ecology of Plant VirusesBarakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principles-of-Bioethics Midterm NotesDocument23 paginiPrinciples-of-Bioethics Midterm NotesAya AbeciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Critical Reading of An Evolutionary Architecture' by John FrazerDocument12 paginiA Critical Reading of An Evolutionary Architecture' by John FrazerbedsonfreÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Land Ethic - Aldo LeopoldDocument21 paginiThe Land Ethic - Aldo LeopoldJuris MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Future of Blind NavigationDocument20 paginiFuture of Blind NavigationchaitanyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contemporary Topics in Biology: Catherine Genevieve Barretto-Lagunzad Faculty, Institute of BiologyDocument15 paginiContemporary Topics in Biology: Catherine Genevieve Barretto-Lagunzad Faculty, Institute of BiologyLea Grace Villazor GuilotÎncă nu există evaluări

- NegOr Q3 GenBio2 SLKWeek4 v2Document18 paginiNegOr Q3 GenBio2 SLKWeek4 v2jenicahazelmagahisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper 1-Machine Learning For Bioclimatic ModellingDocument8 paginiPaper 1-Machine Learning For Bioclimatic ModellingEditor IJACSAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Schaller / Evolutionary Bases of First Impressions 1Document15 paginiSchaller / Evolutionary Bases of First Impressions 1Sriraj DurailimgamÎncă nu există evaluări

- IAI: Machine Learning: © John A. Bullinaria, 2005Document20 paginiIAI: Machine Learning: © John A. Bullinaria, 2005GODFREYÎncă nu există evaluări

- Engineering ProductivityDocument15 paginiEngineering ProductivityGeetha_jagadish30Încă nu există evaluări

- Upsc Mains Questions Anthropology Paper 1 TopicwiseDocument27 paginiUpsc Mains Questions Anthropology Paper 1 TopicwiseadarshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Origin and Evolution of The Genetic CodeDocument7 paginiOrigin and Evolution of The Genetic CodeNarasimha MurthyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revision (Micro Schedules) : Date Day Physics Chemistry Botany ZoologyDocument2 paginiRevision (Micro Schedules) : Date Day Physics Chemistry Botany ZoologyArif Ahmed KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topic Wise Pyqs 1981-2019Document117 paginiTopic Wise Pyqs 1981-2019Neeraj MundaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abstract Sex ParisiDocument236 paginiAbstract Sex ParisiCruellaDevilleÎncă nu există evaluări

- No. of Sessions Dates Topics Reference Prerequisite Competencies First TrimesterDocument6 paginiNo. of Sessions Dates Topics Reference Prerequisite Competencies First Trimesterpamela2pabalanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Earth and Life Science Suppleme Nt-Ary Material S: Second QuarterDocument49 paginiEarth and Life Science Suppleme Nt-Ary Material S: Second QuarterKimberly LagmanÎncă nu există evaluări