Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

English Morphology The Nominal Part

Încărcat de

Melania Anghelus0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

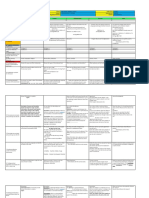

183 vizualizări78 paginiThis document provides an overview of English morphology as it relates to nouns. It discusses several topics:

1. The formation of nouns through affixation, compounding, and conversion from other parts of speech. Common suffixes for deriving nouns from verbs and adjectives are discussed.

2. The grammatical categories that nouns take, including number (singular/plural), case (nominative, accusative, dative, genitive), and gender. The formation of plural nouns and uses of different cases in English are outlined.

3. Exercises are provided to reinforce understanding of noun formation processes and grammatical categories.

Descriere originală:

Titlu original

lec_an1_sem2_cerban_2010

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentThis document provides an overview of English morphology as it relates to nouns. It discusses several topics:

1. The formation of nouns through affixation, compounding, and conversion from other parts of speech. Common suffixes for deriving nouns from verbs and adjectives are discussed.

2. The grammatical categories that nouns take, including number (singular/plural), case (nominative, accusative, dative, genitive), and gender. The formation of plural nouns and uses of different cases in English are outlined.

3. Exercises are provided to reinforce understanding of noun formation processes and grammatical categories.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

183 vizualizări78 paginiEnglish Morphology The Nominal Part

Încărcat de

Melania AnghelusThis document provides an overview of English morphology as it relates to nouns. It discusses several topics:

1. The formation of nouns through affixation, compounding, and conversion from other parts of speech. Common suffixes for deriving nouns from verbs and adjectives are discussed.

2. The grammatical categories that nouns take, including number (singular/plural), case (nominative, accusative, dative, genitive), and gender. The formation of plural nouns and uses of different cases in English are outlined.

3. Exercises are provided to reinforce understanding of noun formation processes and grammatical categories.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 78

ENGLISH MORPHOLOGY

THE NOMINAL PART

MDLINA CERBAN

2

3

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1 - The Noun 5

1.1. Formation of Nouns by affixation and compounding 5

1.1.1. Exercises 7

1.2. The Category of number. 8

1.2.1. Formation of plural nouns. 8

1.2.2. Countability. 10

1.2.3. Uncontable/ no-count . 11

1.2.3.1. Classification of uncountable/no-count nouns.. 11

1.2.3. Exercises.. 14

1.3. The Category of Case. 15

1.3.1. The Nominative case15

1.3.2. The Accusative case 15

1.3.3. The Dative case 16

1.3.4. The Genitive case 17

1.3.5. Exercises.. 22

1.4. The Category of Gender 22

1.4.1. Exercises 25

CHAPTER 2 The Article 27

2.1. The Definite Article27

2.1.1. The functions of the Definite Article27

2.2. The Indefinite Article 30

2.2.1. The functions of the Indefinite Article. 30

2.3. The Zero Article. 32

2.3.1. The functions of the Zero Article 32

2.4. The Omission of the article 35

3.5. Exercises 35

CHAPTER 3 THE ADJECTIVE38

3.1. The form of the adjectives. 38

3.2. The functions of the adjectives 40

3.3. The degrees of comparison 44

3.3.1. The form of the degrees of comparison44

3.4. Exercises 51

CHAPTER 4 THE NUMERAL. 53

4.1. Definition 53

4.2. The Classification of numerals... 53

4.3. Exercises 56

CHAPTER 5 THE PRONOUN.. 58

5.1. The definition of pronouns 58

5.2. The classification of pronouns58

5.2.1. Demonstrative adjectives and pronouns.. 58

5.2.2. Indefinite and negative adjectives and pronouns.. 60

5.2.3. Possessive adjectives and pronouns. 67

5.2.4. Interrogative adjectives and pronouns.. 68

5.2.5. Adverbial adjectives 69

4

5.2.6. Relative pronouns 70

5.2.7. Personal pronouns 72

5.2.8. Reflexive and emphatic pronouns73

5.2.9. Reciprocal pronouns. 74

FINAL EXERCISES.. 76

REFERENCES78

5

CHAPTER 1

THE NOUN

Uniti de nvare :

Formation of nouns by affixation and compounding

The grammatical category of number

The grammatical category of case

The grammatical category of gender

Obiectivele temei:

nelegerea modurilor de formare a substantivelor prin afixare i

compunere

cunoaterea conceptului de categorie gramatical a numrului.

Diferene ntre limba romn i englez

nelegerea categoriei de caz.

nelegerea categorie de gen

Timpul alocat temei : 4 ore

1.1. Formation of nouns by affixation and compounding

Nouns have characteristics that set them apart from other word

classes or parts of speech. According to the 3 criteria, the most important

characteristics of noun are:

1. morphologically , the noun is distinguished from other parts of speech

as regards its form and the grammatical categories (of number, case,

gender).

2. syntactically, nouns can function as subject, object, predicative,

apposition, attribute and adverbial modifier.

3. in point of meaning, the noun denotes objects (beings, things,

phenomena, etc).

A definition such as a noun denotes an object is correct but

incomplete since a noun is also characterized by specific morphological traits

as well as by syntactic functions hence the necessity to define this part of

speech from various points of view. In the present course we are going to deal

with the 2 basic morphological characteristics: their form and their

grammatical categories.

Form: From the point of view of form, nouns can be divided into:

1. simple nouns, these nouns formed made up of a one word which can

not be decomposed anymore, e.g. book, clock.

2. derivative nouns, nouns formed by means of derivational suffixes

(some of the most frequent noun-forming suffixes are :

- er (agential suffix): writer, driver, thriller

- ness: kindness, happiness unique nouns denoting abstract nouns

- hood: childhood, boyhood, denoting abstract qualities

- ing: reading verbal nouns denoting the action

- ion: expectation or state of the respective verbs

- ment: development

6

- let: booklet (diminutive suffix)

In the case of a number of verbs, mainly of French origin, we can find

both a noun derived by means of a suffix and a second noun which is the form

in ing used as noun, e.g. from to develop

a) the development of our economy

b) the developing of new technologies is the chief target

The noun in ing has more dynamic implications and suggests a continue

action. Compare:

a) dezvoltarea (static)

b) procesul de dezvoltare (dinamic)

3. Compound nouns

are made of two or more words representing either homogeneous or non-

homogeneous parts of speech. The semantic relation between the elements of

the compound noun is of two types:

a) endocentric, the meaning of the compound analysed can be deduced

from the meaning of its parts;

b) exocentric, the meaning of the compound cannot be deduced from the

meaning of its parts.

Compound nouns appear in three forms:

as two separate words

as two separate words linked by a hyphene

as one word

The three orthographies depend on the extent to which the two

components are felt to have lost their original meaning or not. That is why

dictionaries sometimes differ with regard to the orthography of compound

nouns are:

a) endocentric:

N + N: post-office, clock-room, classroom (note the three

orthographies). In each case the meaning of the compound is deductible from

the meaning of its parts.

To understand a compound noun, we determine the meaning of the last

term (the Head). The preceding term supplying some information about it,

classroom means room for classes. Mention should be made that compound

noun have the principal stress on the first word, e.g. drug store, post office.

V-ING +N: this pattern is also of the endocentric type. In this

compound the V-ing can be originally:

- a gerund: a sleeping car, working conditions

- a present participle: used as an adjective which can be expended into a

relative (attributive clause: the working class = the class who works.

N+N (derived from verb-er): this pattern is usually of the endocentric

type, e.g. watch-maker, pencil-sharpener

V+N: watch dog, a rattlesnake

ADJ+N: blackboard

b) exocentric:

N + N: ladybird (buburuza), blockhead (netot), butterfly (fluture)

ADJ+N: hotdog, blackleg

4. Nouns formed by means of conversion from other parts of speech.

7

a) from adjective: an adjective may function as a noun if it is preceded by the

definite article

e.g. the good- binele

The supernatural appears in many of Shakespeares plays.

If the converted adjective refers to people it is plural in meaning and

takes a plural verb (it represents a whole class of themes of multitude) the rich,

the selfish

e.g. The rich are often selfish.

The sick are well taken care of in our hospitals.

b) from verb in the form of

(i). the short infinitive of a simple verb: a try

e.g. Let me have a try at it.

(ii). the short infinitive of a complex verb. There are 2 different ways in which

the elements of complex verbs may be combined:

- the verb and particle may simple be joined (sometimes written as one word

as hyphenated - a hyphen can meet the nominalized verb and particle):

e.g. a breakdown, take off, make-up.

- the verb and the particle may be placed in reverse order to form a compound

noun:

e.g. break-out-outbreak; outcome

- the past participle:

e.g. the injured, the wounded (nouns of multitude)

-the ing form

e.g. being, reading, building

Sometimes the gerund takes the definite article and it becomes a noun

on such cases; it is often followed by the preposition of (the verbal noun) e.g.

the swimming

Give examples of noun formation: endocentric

versus exocentric.

1.1.1. Exercises:

1. Attach the appropriate noun-forming suffix: -dom, -hood, -ship, -ist, -ism, -

er, -ful, -ese to each of the following nouns: London, child, Portugal, mouth,

brother, friend, Japan, piano, art, hand, behaviour, teenage, star, impression,

village, boy, Darwin, owner, spoon, member, cello, king, philosophy.

2. Attach the appropriate noun-forming suffix: -age, -al, -ance/-ence, -ant, -

ation, -ee, -er, -ing, -ment to each of the following verbs: develop, use,

embody, write, accpt, receive, descend, paint, employ, upheave, marry,

produce, arrive, defend, house, describe, clean, form, abolish, train, refuse,

happen, enlighten, thrill, inhabit, starve, bathe, cover.

3. Supply a compound nouns in place of the phrase in italics:

1. We have bought a new lamp for reading. 2. You must repair the leg of the

chair. 3. Put this basket on the table in the kitchen, please. 4. The surface of

the road is wet. 5. I remember that the cover of the book was red. 6. Here is

the key of the car. 7. He has just repaired the keyboard of the computer. 8. Not

all of us agree to the policy of the party. 9. Have you locked the door of the

garage? 10. Margaret was very much interested in what the critic of the film

8

was saying. 11. When we got there the door of the cellar was open. 12. You

will have to replace the handle of the suitcase. 13. There were a lot of people

at the gate of the factory. 14. I will ring you up from the phone in the office.

4. Translate into English using compound nouns:

1. Pantofii ti de dans sunt foarte frumoi. 2. Acesta este un vagon de

nefumtori. 3. Gara e la o distan de 5 minute de aici. 4. Eram n faa liceului

cnd am vzut curcubeul. 5. Sindicatele au luat atitudine mpotriva fumatului.

6. Mi-am scos haina de ploaie cnd am intrat n ser. 7. Camerista a fcut o

depresie nervoas. 8. Redactorul-ef e plecat n cltorie de afaceri. 9.

Zborurile de noapte sunt foarte rare. 10. Am observat urme de pai pe prag.

1.2. The category of number

The English noun has 2 numbers: singular and plural.

The singular is that form of the noun which denotes either one object (a book)

or an indivisible whole (money). The plural is that form of the noun which

indicates more than one object (book). When we are talking of the category of

number in nouns, there are 2 aspects that should be taken into account:

1.2.1. Formation of the plural number

a) regular plural forms: Nouns generally form their plural in a regular

predictable way by adding s to the simple form, to the singular form, e.g.

books, days

In adding s some spelling rules should be observed:

- nouns ending in a sibilant sound in the singular (spelt with s, -ss, -x, -

ch, -sh, -zz) add es, in the plural (pronounced (iz):

e.g. class/es, churh/es, box/es, wish/es, watch/es

Exceptions: when -ch is pronounced (k) epoch/s, stomack/s, monarch/s

- nouns ending in y follwing a consonant form their plural by dropping

the y and adding es:

e.g. country-countries, duty-duties

- nouns ending in y following a vowel form their plural by adding s

e.g. play-plays, boy-boys

- twelve nouns ending in -f(e) add es with -f changing into v:

e.g. calf/ calves, life, knife, half, leaf, loaf, self, shelf, thief, wife, wolf, elf

Exception: roof/s, chief/s, handkerchief/s

- nouns ending in o, add es

e.g. potato/es, tomato/es, hero-/es

Exception: piano/s , soprano/s, radio/s, photo/s, zero/s

b) Irregular plural forms: there are nouns preserved from Old English which

form their plural as they did in Old English by means of internal vowel

changes or mutation, e.g. man/men, woman/women, tooth/teeth, goose/geese,

foot/feet, mouse/mice, mouse/lice or by adding en to the singular , e.g.

child/children, ox/oxen, brother/brethren (fellow members of a religious

society)

c) Foreign plurals: a few nouns of Latin or Greek origin retain their original

plural forms, they form the plural according to the languages, were borrowed

from:

- is > -es:

9

e.g. crisis/crises, basis/bases, analysis/analyses, thesis/these,

parenthesis/parentheses

- um >-a:

e.g. symposium/symposia, stratum/strata, medium/media, erratum/errata

- on > -a:

e.g. criterion/criteria, phenomenon/phenomena

- us >- i:

e.g. fungus/fungi, nucleus/nuclei, radius/radii, stimulus/stimuli

- a >- ae:

e.g. formula/formulae, alga/algae, larva/larvae, vertebra/vertebrae

- ex >- ices:

e.g. index/indices, appendix/appendices, matrix/matrices

There is tendency for some foreign nouns adopted in English to

develop regular plural forms, without losing the original forms. When both

forms are used the foreign one is more formal, which means that formulae

occurs in technical and scientific texts while formulas in everyday speech.

There is quite a large number of nouns (not necessarily of Latin origin)

which have double plural forms implying changes of meaning:

e.g. SINGULAR PLURAL

arm (bra) arms (brae; arme)

cloth (material) clothes (stofe, materiale); clothes (haine)

colour (culoare) colours (culori; drapel)

glass (sticl, pahar) glasses (pahare, ochelari)

d) Plural of compound nouns: compound nouns follow some definite rules

of plural formations, depending on the elements that make up of the

compound:

- in most compound nouns (N + N), the last element assumes the plural

form

e.g. horse-races, grown-ups, postmen

- in compounds composed of N + PREPOSITION + N, the first element

assumes the plural form

e.g. editor-in-chief/ editors-in-chief, sister-in-law/ sisters-in-law

- in compound nouns made up of N+ PARTICLE/PREPOSITION the

first element assumes the plural form

eg. looker/s-on, passer/s-by

- in compounds made up of VERB (without nominal ending) +

ADVERBIAL PARTICLE the last element assumes the plural form

e.g. take-offs, breaks-in

- if the word man or woman forms the first part of the compound, both

nouns assume the plural form

e.g. man-servant, men-servants, women-doctors

- in compounds consisting a N in their structure the last element assumes

the plural

e.g. merry-go-round/s, forget-me-nots

How is the plural of regular nouns formed?

State the rules of forming the plural of compound nouns.

Give 10 examples of foreign plurals.

10

1.2.2. Countability

The most common manifestation of the category of number is reflected

in the notion of countability with presupposes the possibility of counting

objects. From the point of view of countability, English nouns can be divided

into 2 classes:

1. countable nouns are those nouns that can be counted, those nouns

that can be distinguished as separate entities. Count nouns have the following

characteristics:

- they are variable from the point of view of number, they have both

numbers in the singular and in the plural, eg. student/s, man/men,

criterion/criteria

- since they can distinguished one entity from others, they can be

individualized by means of determiners who cause quantifiers and/or number;

thus they may be preceded by the following determiners:

- in the sg: both art. : a(one), the determinatives, each, every, this/that,

no, the numeral one;

- in the plural: the article: the, the determinatives, these/those, once, any,

no, many, a few, several, numbers from 2 onwards

- they agree in number both with the verb and with the determiners. Thus, a

singular noun requires a singular verb and a singular determiner, while a plural

noun requires a plural verb and a plural determiner.

Those nouns that meet the 3 conditions mentioned above are countable

nouns.

a) individual (common) nouns, eg. student/s

Such nouns have the 3 characteristics mentioned above, eg. This book is

interesting. Those books are interesting. The vast majority of nouns in English

follow this pattern.

b) collective nouns are those nouns that semantically collect a number of

similar objects (usually of persons) into one group. Such nouns are: army,

assembly, audience, board, class, committee, family, flack, government,

group, jury, party, staff, team. These nouns are variable in form, meaning that

they have both numbers singular and plural. In this respect they behave like

individual nouns proper. A singular noun may take agree with a singular or a

plural verb, a family several families.

- a singular noun takes a singular verb when it refers to the group as a

whole as a unit. The noun behaves like an individual noun

e.g. The average family which now consists of 4 members at most, is a

great deal smaller than it used to be.

The committee is preparing its support.

Our team is in the second division.

Note that in this case the nouns are preferred to by inanimate singular pronoun

it, which.

- a singular noun may take a plural verb when the speaker or writer is

thinking more of the individual members/persons that make up the group (than

of the group itself).

- when such a noun in the singular refers to the separate members of a

collectivity, it behaves like a collective noun, as if it were plural, the

consequence being that.

11

Although singular in form the noun agrees with a plural verb and it

also referred to by the animate plural, pronouns they, who.

e.g. My family are being and supportive; they are always ready to help me.

I dont know any other family who would do so much (the members of

my family).

The team are playing very well, arent they?

The government are discussing the new development scheme

(reference is made to the individuals that make up the act).

c) Some nouns with the same form for the singular and the plural have no

special form for the category of number: considering that the basic form is that

of the singular, we can say that they receive (unmarked nouns) a zero ending

in the plural. In spite of the fact that they are no variable in form, they are

considered to be countable nouns because they meet the others 2 conditions,

verbs and determiners with such nouns are either singular or plural according

to the meaning expressed by the nouns.

- some nouns ending in s : means , series, species (also headquarters,

works (factory)

e.g. A new means of transport is the hovercraft.

The fastest means of transport are not always the most comfortable.

This is a rare species.

- some nouns denoting animals (sheep , deer, also aircraft)

e.g. There is a stray sheep on the road. There are some stray sheep on the

road.

- some names of nationality : Chinese, Japanese, Swiss.

What are countable nouns? Give examples.

1.2.3. Uncountable /no-count nouns

They are invariable in form, having only one form either singular or

plural. They agree with the verb and determiners only in the singular or only

in the plural.

1.2.3.1. Classification of uncountable/no-count/ invariable nouns.

The nouns generally treated as uncountable nouns in English can be divided

into the following groups:

a) singular uncountable nouns

They have the following characteristics:

- they are invariable in form having one form : singular (they have no plural)

- since they dont express the opposition between singular and plural they

cannot be determined by means of quantifiers or numerals. They cannot be

used with the indefinite article a or with the determiners each, many, few,

these, those. The only determiners that can be used with uncountable nouns

are: the, this / that, some/anywhere, much, a little.

- they agree with the verb and the determiners only in the singular. In point of

meaning the nouns can be divided into:

12

(i). mass/material nouns: they denote concrete things looked upon as a

whole, as indivisible entities which can not be counted as: bread, butter, chalk,

coffee, fish, gold, oil, salt, snow, steel, water, etc.

e.g. Water is pleasant to drink when cold,

Steel is much more resistant than copper.

He loves to drink wine.

Fruit is good to eat. Lets have some fruit for desert.

Some other uncountable nouns denote a whole composed of various units:

equipment, furniture, jewellery, luggage, baggage, money, machinery.

e.g. Where is your luggage?

The money is in the wallet.

Note: moneys: fonduri monetare, incasari.

(ii). abstract nouns: the class of abstract nouns is more extensive in English

than in Romanian,

e.g. advice, applause, business, cruelly, evidence, homework, income,

information, injustice, knowledge, progress, strength, trouble, thunder (most of

them are countable in Romanian).

e.g. His advice is always good.

He felt his strength was failing.

Your information is not reliable.

His progress in English is highly satisfactory.

Her knowledge of history is poor.

Note: Knowledge may take the indefinite article when is used in a particular

sense.

e.g. He has a good knowledge of mathematics.

Businesses intreprindere, localuri sedii de intreprindere

Uncountable nouns (both mass and abstract ones) can be individualized ,

quantified by means of:

1. partitive expressions like: a piece of, an item of, a bit of, an act of

e.g. a piece of chalk, a piece/word of advice, an act of cruelty/ injustice, a

piece /stroke of luck

2. by referring to a piece / part of a certain shape or to a container

e.g. a loaf of bread, a sheer of paper, a flash of lightning, a bar of soap

Some uncountable nouns in s: news, as well as nouns denoting sciences

in ics, (physics, linguistics, mathematics, athletics); some diseases (measles,

mumps, rickets); some games (billiards, darts, dominoes)

e.g. Near is the news /BBC announcement.

Draughts is an easier game than chess.

Some uncountable nouns can become countable ones, and therefore, can

be used in the plural or can be preceded by the indefinite article a (one) whom

they refer to varieties of things or when they denote a particular kind of things.

e.g. The steels of this plant are of very good quality.

Many different wines are made in France.

Various fruits were on display at the greengrocers.

The fishes of the Black Sea are good.

glass:

13

- uncountable (the material). e.g. Windows are made of glass.

- countable (the container). e.g. Give me a glass of water.

Paper:

- uncountable (the material). e.g. The box was wrapped in paper.

- countable (test). e.g. He has written a good paper.

Iron:

- uncountable (the material). e.g. This tool is made of iron.

- countable (tool, implement used for smoothing clothes). e.g. He has got a

new iron.

Youth:

- uncountable (the state of being young ). e.g. The enthusiasm of youth.

- countable (a young person). e.g. Half a dozen of youths were waiting outside.

b) Plural Invariable Nouns (Pluralia tantum)

They are invariable in form, having only one form, that of plural, they

only occur in the plural and are never used at the singular.

- they agree with the verb and determiners (the, these/those) only in the plural

- in point of meaning, the nouns included in his group refer to...

a. summation plural: article of dress or instruments/tools who are composed of

similar parts

e.g. clothes, jeans, pants, tights, trousers, shorts, binoculars, glasses,

scales, scissors, tangs.

These trousers are too long for you.

Where are the scissors?

The nouns can be individualized/ quantified by means of the partitive

expression a pair of.

Other nouns that only occur in the plural: firewall, goods, dregs, proceedings,

wages, annals, outskirts, surroundings. In many cases there are forms without

s, sometimes with a difference of meaning, there are some nouns with have

difference meanings when used in the singular and in the plural as invariables

Nouns in - s have two meanings in the plural

e.g. content-contents; compass-compasses; custom-customs; brain-brains;

colour-colours; damage-damages; effect-effects; ground/s

c) Nouns of multitude (unmarked plural, zero plural)

There are some nouns who with the verb in the plural although they are

not marked formally for the plural , they have a form in the singular

e.g. cattle, people, police, youth, clergy

The cattle are grazing in the field.

There are a lot of people in the street.

The youth of today do not know what they want.

Note: do not confuse the noun of multitude people (=human beings) with the

countable noun a people (=nation) who is regular.

There is also a noun of multitude youth (=young people) with countable

noun youth (=young person)

d) substantivized adjective and participle

(i) adjective and past participle used with the definite article

14

There arent very many substantivized adjective of this kind in

English, the construction is not productive. Most other adjective can not be

used in this way.

e.g. we cannot say: the foreign (=the foreign people), but we can say the

happy ( = the happy people), the old, the rich, the poor, the sick, the

wounded.

The rich get richer while the poor get poorer.

(ii). also adjective of nationality ending in sh, -ch,: the British, the English,

the Scotch, The Dutch, the Spanish, the French.

e.g. The Scots have the reputation of being thrifty.

What are uncountable nouns? Give examples.

1.2.3. Exercises:

1. Form the plural of the following nouns: fellow-citizen, passer-by, man-

eater, woman doctor, man-of-war, take-off, footstep, cameraman, sister-in-

law, potato, echo, leaf, roof, ski, sky.

2. Supply the plural of the following nouns of Greek and Latin origin: bacillus,

addendum, series, datum, crisis, schema, stimulus, criterion, phenomenon.

3. Choose the appropriate form of the verb. Note the difference in meaning

with the nouns that take both a singular and plural predicate:

1. His phonetics is/are much better. 2. My trousers is/are flared. 3. The scissors

is/are lost for ever. 4. Statistics show a great interest in ecology. 5. Youth

today is/are turning from church nowadays. 6. What is/are your politics? 7.

The acoustics of the National Theatre is/are excellent. 8. What is/are cattle

good for? 9. Fresh-water fish include/ includes salmon, trout and eel. 10. The

police as/ have made no arrest yet. 11. It is generally accepted that bad news

dont/ doesnt make us happy. 12. The class was/were warned not to talk

during the test. 13. Mumps is/are very painful ailment. 14. A number of cars

was/ were involved in the accident. 15. The council was/ were unable to agree.

16. One of the girls has/have lost her umbrella. 17. Fish and chips is/are a very

popular meal in England. 18. Either the boys or the girl help/helps the woman.

19. Advice is/are given on all the technical aspects. 20. The Italian clergy was/

were opposed to divorce.

4. Translate into English:

1. Casa lor nu este mare, dar mprejurrile sunt ncnttoare. 2. Casa lor este

lng o intersecie aglomerat. 3. tirile sunt cu adevrat interesante. 4.

Secretara ne+a dat procesul+verbal al edinei de ieri. 5. Brbatul pretindea

despgubiri. 6. Soldaii au salutat drapelul regimentului. 7. Dup un zbor de

trei ore am ajuns la destinaie. 8. Biliardul este un joc interesant. 9. Era un

spectacol minunat s admiri rsritul soarelui de pe stnci. 10. Simeam o

durere acut n piept. 11. Avem nevoie de un compass ca s desenm cercul.

12. Asemenea fenomene sunt greu de explicat. 13. Am cumprat o pung de

cartoi de trei kilograme. 14. Ipotezele sale s-au dovedit corecte. 15. Toate

criteriile de evaluare pot fi ndeplinite cu uurin. 16. Sfaturile lui nu sunt

utile. 17. Am o mulime de teme de fcut pn mine. 18. Progresele realizate

15

de echip au fost observate de toat lumea. 19. Tocmai am trecut cu bagajele

prin vam. 20. Ochelarii bunicii au fost spari de nepotu su din neatenie.

1.3. The category of Case

Case is the grammatical category that indicates the relationship

between certain parts of speech (in particular between nouns). The

grammatical category of case can be marked, in synthetic languages by

inflections and in analytical languages by word order or prepositions.

Old English was characterized by a great number of inflections with

the consequence that there were four cases with distinct endings. In the course

of its historical development, the English noun has lost its former case system.

Thus, case which morphologically is a very complex grammatical category in

many European languages such as German, Russian, Romanian and many

other languages, is not very significant for the English noun. The

morphological structure of the noun is uniform irrespective of its relations and

functions. As a result of the general tendency towards analytical instead of

synthetic forms, case inflections disappeared. The English noun has, however,

the -s ending in the Genitive.

The loss of distinct case forms has been compensated by a stricter

word order in the sentence and the use of a large number of prepositions. The

question that arises is whether the disappearance of case inflections is general

among grammarians.

Those who pursue a formal approach restrict of number of English

cases to two:

- the common case (Nominative, Dative, Accusative) - unmarked

- the possessive case (Genitive) marked in s

Those who pursue a functional approach (besides form, the category of

case implicitly entails context and syntax) consider that there are 3 cases in

English:

- the Nominative used for subjects

- the Genitive used to indicate possession (This case in frequently termed

possessive although the purpose of its meaning is wider than possession (in

the normal sense of the world).

- the Objective Dative and Accusative used for objects of a verb or

preposition.

1.3.1. The Nominative case is the case of nouns that display the

function of a Subject, predicative or apposition in the sentence.

1.3.2. The Accusative Case is used with nouns that express the

function of Direct Object or of adverbial modifier. The old distinctive

inflections for the Accusative case have disappeared, their function being

taken over by strict word order:

e.g. The hunter killed the lion.

The lion killed the hunter.

A noun in the Accusative case is used after:

a) transitive verb to denote the objective that undergoes the change. If there is

only one object in the sentence, it gets the position immediately after the verb.

e.g. I read a book last night.

16

After some ditransitive verbs which may have 2 objects:

- the verbs to ask, to envy, to forgive may be followed by 2 objects in the

Accusative

e.g. The teacher asks the people several questions.

I envy John his garden.

- V+ objective animate + objective inanimate: the verbs to give, to hand, to

offer, to pay, to read, to show, to tell, to throw, to write, to wish are usually

followed by an indirect objective in the Dative and a direct object in the

Accusative.

e.g. I gave John my book.

b) some intransitive verbs changing them into transitive ones.

e.g. some intransitive verbs having the same root as the noun in the

Accusative (a Cognitive Object): to smile a bright smile, to live a bad

life, to fight a terrible fight.

c) prepositions: most prepositions in English are followed by (pro)nouns in the

Accusative.

1.3.3. The Dative Case is used with nouns that display the function of

Indirect Object. In present day English, the dative is marked either by

prepositions (to, sometimes for) or by strict word-order among the nouns of

the sentence. A noun in the Dative case is used after the following parts of

speech.

a) verbs:

- transitive

- intransitive

- some intransitive verbs followed by an indirect object of person: to happen,

to occur, to propose, to submit, to surrender, to yield,

e.g. It happened to my brother.

An idea occurred to John.

- some transitive verbs followed by 2 objects (If the indirect object is placed

before the direct objective, the prepositions to is omitted).

e.g. I paid the money to the cashier. I paid the cashier the money.

I am writing a letter to my friend. I am writing my friend a letter.

There is a number of verb obligatory followed by the preposition. In

these cases with the preposition to the indirect object is placed before the

direct object: to address, to announce, to propose, to relate, to repeat.

e.g. I introduced him to my mother. I introduced to my mother all my

friends.

- V + DO + (FOR). A direct object and an indirect object preceded by the

preposition FOR: to buy, to allow, to do, to leave, to make, to order, to

reserve, to save, to speak (The preposition FOR is omitted if the indirect

object is placed before the direct object)

e.g. She brought a present for her mother. / She brought her mother a

present.

She made a new dress for her daughter. / She made his daughter a

new dress.

17

b) some nouns: attitude, cruelty, kindness, help, promise, duty

e.g. Her attitude to animals surprised us. He kept his promise to his friend.

c) some adjectives of the same semantic field: cruel, kind, good, polite,

helpful, grateful, rude

e.g. Dont be cruel to animals.

I am grateful to the friends who help me.

She advised me to be kind to her.

d) Also adjectives involving a comparison: corresponding, equal, equivalent,

similar, superior, inferior, prepositional.

e.g. The result was not equal to his efforts.

Man is superior to animals.

1.3.4. The Genitive Case

The noun in the Genitive case expresses the idea of possession and

discharges the syntactic function of an attribute. There are 2 forms of

Genitive:

I. The Synthetic Genitive

Form: in English, the genitive is marked by the ending -s preceded by an

apostrophe. In present-day English there are 2 ways of marking the synthetic

genitive in writing:

- the apostrophe + the ending s are added to the singular form of nouns:

e.g. the girls name

and to unmarked plural noun or irregular in the plural:

e.g. the mens clothing, the childrens toys.

- the apostrophe is added to the plural form of regular nouns (the boys

teacher); to proper names ending in s (Dickens novels).

The Group genitive (Possessive): Compounds as well as noun phrases

denoting one idea are generally treated as one word and the genitival suffixes

are attached to the last elements of the group who may not be known rather

than to the head.

e.g. the queen Englands throne.

The group genitive is not normally acceptable following a clause.

e.g. A mums son I know has just been arrested.

In a group of words made up of a noun apposition the genitive mark is added

to the apposition.

e.g. Have you seen my brother Jimmys car?

Two nouns coordinated by and representing the possessors of the same object

take s after the last word.

e.g. Tom and Marys parents. (Tom and Mary are the possessors of the

same object, are brothers).

If they represent the possessors of different object, each noun receives the

suffix.

e.g. Toms and Marys parents.

18

Jasons and Shakespeares plays.

The position of the noun in the Genitive case

a) The noun in the genitive the determiner usually precedes the determined,

the noun in the nominative.

e.g. This is Marys bag.

b) The genitive with ellipsis

The noun in the genitive can appear by itself, the noun modified by the s

genitive may be omitted. This is possible when:

- the determined noun has been mentioned previously and the speaker wants to

avoid the repetition (if the context makes its identity clear).

e.g. This is Toms book. Marys is on the table.

- the determined noun denotes residence, establishment institutions, buildings,

represented by such nouns as shop, office, house, place, cathedral, store.

e.g. She went to the chemists shop.

I went into a stationers shop to buy a postcard. I was at the Browns

yesterday. St Pauls cathedral is one of the sights.

c) N+N Genitive

The noun in the syntactic genitive can follow the determiner noun in a Double

Genitival Construction. The double genitival is a construction which consists

of the two types of genitive: the prepositional Genitive (framed with

preposition of) combined with the syntactic Genitive. The double genitive is

used with the following values:

(i). a partitive meaning

e.g. A cousin of his wifes (one of his wifes cousins).

He is a friend of Johns (one of Johns friends).

The determined nouns must have indefinite reference (indefinite

article), it must be seen as one of an unspecified member of items attributed to

the post-modifier.

(ii). The double genitive differs in meaning from the prepositional genitive.

- a description of genitive (a description made by some body else about

genitive):

e.g. A description of Galsworthys (one of genitives description, a

description made by genitive)

- a description or emotional implication it expresses various shades of

subjective attitude the speakers contempt, arrogance, dislike (The noun is

determined by the demonstrative).

e.g. That child of Anns is a nuisance. That remark of Johns was

misplaced.

The uses of the synthetic genitive

The synthetic genitive is generally used in the following categories of nouns.

a) animate nouns, mainly with nouns denoting living beings:

- nouns denoting persons and proper names:

e.g. the boys book

- collective nouns (who indicate in effect a body of people):

19

e.g. The governments decision; the companys officials

- indefinite pronouns referring to persons (somebody, nobody, everybody,

another, either):

e.g. nobodys fault, everyones wish

-large animals:

eg. the lions mouth.

b) Some clauses of inanimate nouns:

- geographical names (names of continents, countries, cities, looked upon in a

political or economic sense.

e.g. Europes future; Londons museums

- nouns denoting institutions:

e.g. the schools program.

-natural phenomena:

e.g. the suns rays, the earths atmosphere

- nouns denoting units of time (temporal nouns):

e.g. New Years Eve, a days journey

- nouns denoting distance, measure, value:

e.g. a miles distance, a pounds worth of sugar.

- personifications:

e.g. Loves Labours Lost; lifes joys.

- set phrases:

e.g. in my minds eyes, at ones fingers end, the ones hearts content

The meanings of the genitive

1. possessive: this value, most frequently associated with the syntactical

genitive

e.g. my fathers car = my father has a car.

The boys book = the boy has a book.

2. subjective (the determiner is a subject while the determined noun is the

object):

e.g. the girls story = the girl told a story.

3. objective (the determiner is an object):

e.g. the prisoners release = release the prisoner.

4. classifying. The previous examples the genitive (the first name) has a

particular meaning

e.g. my fathers ca r- my father is a particular individual some genitive

expression have a class meaning.

It is equivalent to relative adjective. The use of the indefinite article

changes the noun in the genitive into a relative adjective.

20

e.g. childrens magazine a magazine for children

a womans college a college for women.

II Analytical Genitive (The prepositional genitive)

In the middle English, the analytic means of expressing the genitive

(the preposition OF +Noun) placed after the determined noun, came to

complete with the syntactical form, and today the Accusative has replaced the

syntactical genitive in some of its uses.

The analytic genitive is used with the following types of nouns:

- inanimate nouns: the title of the book, the roof of the house, the bend

of the river, the member of the faculty.

- some geographical names:

- in appositions: the city of London, the golf of Mexico.

- when the geographical names are looked upon from a partly

geographical point of view: The boundaries of Switzerland are...

- animate nouns may take the Analytical Genitive instead of Synthetic

Genitive

- for the sake of emphasis (when we went to emphasize the animate

noun the proper names, much as in titles), the focus of information

falls on the last word: Shakespeares plays = The complete works of W

Shakespeare; The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

- When the determiner (the noun in the genitive) is a part of a complete

noun phrases, and it is determined in its turn.

-

e.g. The name of the man over there, at the table, who came yesterday.

The Synthetic Genitive may follow one another in a sentence if both

possessors are animate: a syntactic genitive may give another Synthetic

Genitive

e.g. Marys brothers friend.

My cousins wifes first husband.

But the use of the Synthetic Genitive with both nouns is rarely found in

speech. It is preferred to express to former genitive by a prepositional

constructions, the latter by the Synthetic Genitive. In some cases there is a

functional similarity between a Synthetic Genitive and an Analytical Genitive

(the S.G. and the A.G. are in free variation). Thus, both structures are possible

in: The gravity of the Earth / The Earths gravity. The S.G. is used in

newspapers headlines, perhaps for reasons of space economy:

eg. Fire at U.C.L.A. Institutes roaf damaged. While the subsequent news

item begins The roaf of a science institute on the compres was damaged last

night.

III The Implicit genitive

Many of the meaning characteristic of the genitive can sometimes

rendered by word order alone. The I.G. is rendered by the mere juxte-position

of 2 nouns without any formal mark. (without the suffix s or the preposition

of) which might be expressing the relation between them. In this simple

construction who is nothing that a compound noun, the first noun assumes a

determining role, it assumes the value of an attribute, thus preceding the

determined noun.

The I.G. can replace both syntactic genitive and analytic genitive.

21

In contemporary English, the I.G. appears chiefly in:

- titles names of organization : UNO (The United Nations organization)

- newspaper headlines: This kind of structure is extremely common, because it

saves place:

e.g. Death drug research centre spy drama expressions like these can be

understood by reading when bookwords. The headline is about a drama

concerning a spy in a centre for research into a drug that causes death.

I. The I.G. may be often replace a Analytical G. (a postdeterminer) by

meaning of a predeterminer: N1+(OF+N2) = (N2). N1.

e.g. a member of the faculty a faculty member, the Genitive a

postdeterminer is replaced by a predeterminer such as: the bank of the river,

the strings of the violin are transformed into I.G: the river bank, violin strings.

As a rule, I.G. issues mostly to describe common, well known kinds of

things; compounds are widely used, while for concepts which are not so well

known we use prepositional genitive.

Compare: mountains top, a tree top, but the top of a loudspeaker.

Sometimes, the different structures express different meanings.

Compare:

A cup of coffee - A coffee cup

A box for matches - A match box

We use the prepositional structure to express possession, to talk about

a container with its contents.

e.g. A cup of coffee = a cup containing coffee

A coffee cup = a cup for coffee

A box of matches = a box with matches in it

A match box = (perhaps empty)

II. The Implicit Genitive is used instead of the syntactic genitive in

expressions of time and distance.

In expression of time or distance beginning with a numeral, the S.G. can be

used as an adjective.

e.g. a five hours talk a five-hours talk; a ten minutes break a ten-

minute break.

a three miles distance a three-mile distance

As a rule the IG is more general than the syntactic genitive (who has a

more limited reference). Thus, the syntactic genitive is used when the

determiner is a particular individual while the IG is used when the determiner

usually refers to a whole class:

e.g. That cars engine is making a funny noise. (The SG is used to refer

to).

A car engine usually lasts for about 80,000 miles.

A Sundays paper (a paper that comes out on Sunday)

Please, put the dogs food under the table (the determiner dogs is a

particular individual: the dogs food is the food that a particular dog is

going to eat)

Dogfood costs merely as much as a steak, the structure in which the

noun is used as adjective: dog refers to a whole class: dog food is food

for dogs in general.

22

How many forms of Genitive are there in English?

Can you give examples of Implicit Genitive?

Name the differences between the Synthetic and the Analytical

Genitive

1.3.5. Exercises:

1. Join the two nouns in order to form a genitive. Sometimes you have

to use an apostrophe with or without s, sometimes you have to use the

analytical genitive:

1. the coat/ Jimmy. 2. the newspaper/ yesterday. 3. the wife/ the man crossinf

the street. 4. the neighbours/ my parents. 5. the roof/ house. 6. the mane/ my

friend. 7. the name/ that river. 8. the dress/ the girl we met yesterday. 9. the

policy/ government. 10. the marks/ the boy and the girl.

2. Write the following sentences inserting the possessive form of the

noun given in the brackets at the end of each:

1. The .. concert was most amusing (babies). 2. They did not see the ...

signal (policeman). 3. She stayed five days on her farm. (friends) 4. Our

welfare should always come first. (country) 5. The clinic has large stocks of

foods. (babies). 6. The leg was broken in that accident. (tourist). 7. The

meeting was held in the staff room. (teachers) 8. The face was met with

tears. (baby).

3. Translate into English:

1. Casa prietenei lui Nick este foarte frumoas. 2. Ideile colegului fratelui meu

sunt interesante. 3. Cteva dintre jucriile copilului verioarei mele au fost

recent cumprate. 4. Caietele colegului lui Dan sunt foarte ordonate. 5.

Acestea sunt rezultatele testului de ieri. 6. Din avion am avut o vedere de

ansamblu a ntregului ora. 7. Dup o pauz de zece ore ne-am continuat

cltoria. 8. Membrii comitetului se vor ntlni peste trei zile. 9. Sunt sigur c

dup o vacan de dou sptmni de vei simi mai bine. 10. Maina

directorului liceului este parcat n faa colii.

4. Translate into English using the two forms of the Dative wherever

possible:

1. I-am trimis fiului meu nite bani. 2. Tu i-ai dat fetiei dou jucrii. 3.

Spunei-i secretarei numele dumneavoastr. 4. Doctorului i-a prescris un alt

medicament pacientului. 5. n fiecare diminea i spune la revedere bunicii

sale. 6. Le-a explicat bieilor regulile noului joc. 7. Prinii i cumpr un

ghiozdan nou surorii mele n fiecare an. 8. I-a scris o scrisoare mamei sale. 9.

Vrei s l prezini pe Tom prinilor ti_ 10. I-am oferit tnrului absolvent o

slujb foarte bun.

1.4. The category of Gender

Jespersen defines gender in the following wayby the term gender we

mean any grammatical division (presenting some analogy to the distinction

between masculine, feminine and neutral whether that division is) either based

on the natural division into the 2 sexes (M and F) or that between animate and

inanimate.

23

Some grammarians make the difference between grammatical gender

and natural gender. In most European languages gender, to a large extent, is

grammatical.

The irrelevance (the arbitrary character) of any kind of meaning to

gender can be illustrated by comparing the genders of some inanimate nouns

in several languages. Let us compare the gender of the nouns SUN and

MOON in some the Romance languages and German. In the Romance

languages sun is Masculine and moon is Feminin (R- soare, Fr- soleil, It-sole,

Sp-it sol; R- luna, Fr- la luna, It- le luna); but in German, sun is feminine and

moon is masculine (die Sonnes, der Mond).

In English, gender is to a large extend natural in that the connection

between the biological category sex and the grammatical category gender is

very close; in so far as sex distinction determine English gender. Thus, nouns

denoting beings (persons, sometime animals) are either masculine or feminine

(depending on whether they denote male or female beings) while inanimate

nouns are neuter.

In most European languages gender is a grammatical category, being

marked formally on the one hand the masculine and feminine nouns have

distinctive endings, on the other hand, articles and adjectives agree with the

noun in gender. Unlike in such languages in English the gender is rarely

marked for formally.

The grammatical category of gender is marked in 3 ways in English:

1) Lexically; 2) morphologically; 3) using gender markers.

1) Lexically, the masculine and the feminine can be indicated by means

of different words:

- For personal nouns: man/woman; boy/girl; brother/sister, etc

- For animate nouns (higher animate when sex difference is felt to be

relevant): stallion/mare; cook/hen.

2) Morphologically: by means of specific derivational suffix which is added to

the masculine in order to form the feminine.

-ess: prince-princess; host-hostess; actor-actress; duke-duchess

-ine: hero-heroine

-ette: usher-usherette

-ix: administrator-administratrix

These derivational suffixes are not productive, however they are not

regular, we can not form teacheress, doctoress on the pattern host /hostess.

The usual derivational suffix applied to animate nouns in ess

e.g. Lion/lioness; tiger/tigress

3) A number of nouns denoting a persons stares, function, profession has a

single form used both for masculine and feminine (the Common Gender or the

Dual gender):

e.g. artist, cook, cousin, doctor, enemy, foreigner, friend, guest, librarian,

neighbour, pupil, speaker, student, teacher, writer, worker.

Take out of the contrast, such nouns can be ambiguous (we do not

know whether they are M and F). The gender of such nouns can be identified

by means of words that mark gender. (gender markers).

a) the gender of such nouns is usually identified in a context by means

of pronouns with refer to nouns and who have different gender forms in the 3-

rd person singular (personal and reflexive pronouns, possessive adjective).

24

e.g. The teacher asked the pupil a few more questions, the sentence is

ambiguous to the gender of the 2 nouns, but it can be distinguished if

we add

. as she wanted to give him a better mark

When such nouns are used generically (neither gender is relevant), a

Masculine reference pronoun may be used (another solution would be to use

he or she),

e.g. He any student calls, tell him.

With nouns denoting large animals the choice of the pronoun can be a

matter of sex (he replaces male animals, she-female animal). When used

generically, such nouns denoting large animals are usually considered

masculine being replaced by the pronoun he.

The pronoun it usually replaced small animals and optionally all animals even

when sex is known.

A bull-can be he, it

A cat- can be he, she, it.

e.g. The horse was restive at first, but the soon be come manageable.

Gender in animals is chiefly observed by people with a special concern

(e.g. Fat animals are called she or he when they are thought of as having

personality intelligence by their owners, but not always by other people).

b) Besides pronouns, disambiguation with respect to gender is also possible by

using some words marking gender (gender markers such as boy/girl,

man/woman, male/female.

e.g. boy friend/girl friend, salesman/saleswoman,

policeman/policewoman.

This is not very productive because there are many words in which the

distinction do not work.

Others, chairman, for instance, do not change: in Great Britain a

woman who presides over a committee is still called a chairman Madam

Chairman although there is a tendency to replace words like this by forms

like chairperson.

With large animals, he/she, cock/hen can be used as gender workers.

e.g. he-goat; she-goat; cock-sparrow/hen-sparrow.

2. The stylistic use of the grammatical category of gender

Normally masculine nouns denoting inanimate things, are usually replaced by

it.

a) Some nouns denoting inanimate things, which are neuter in everyday

speech, are sometimes personified in literature.

The masculine gender is usually ascribed to nouns denoting strength,

violence, harshness; e.g. wind, ocean, sun, while the feminine gender is

ascribed to nouns denoting delicacy, tenderness or less violent forces: nature,

liberty, moon.

Let us compare 2 sentences, one from literature when the moon is

personified and the other in a neutral style.

e.g. The moon has risen. How pale and ghostly the roofs looked in her

silvery light!

25

The moon has no particular importance, except to the earth which it

attends as satellite.

Sometimes, the distinctions depend on the authors imagination and

intention. In other words, English writers are quite free to refer nouns and

lifeless things to any gender when personified. An example in point is The

Nightingale and the Rose where Oscar Wilde makes the Nightingale of the

feminine gender and the Rose tree of the masculine gender.

e.g. the rose-three shook his head and said: My roses are yellow.

b) In everyday speech, there are a number of derivations from the normative

pattern.

- nouns such : ship, boat, car often used as feminine (are often referred to as

her, she) the speaker conveying the fact he regards them with affection, that he

considers as close or intimate to him.

e.g. The ship struck an iceberg which tore a large hole in her side.

- names of countries when looked upon from the political or economic point of

view.

As geographical units, names of countries are treated as nominate:

e.g. Looking at the map we see France. It is one of the largest countries in

Europe.

As political /economic units, names of countries are often feminine.

e.g. France has been able to increase her deports by 10% cent.

- the nouns: baby, infant, child can be neuter and referred to by it:

e.g. She began nursing her child again.

Another is not likely to refer to her baby as it, but it would be quite

possible for somebody who is not emotionally connected with the child to

replace such nouns by it.

How is gender marked in English? Give

examples.

1.4.1. Exercises:

1. Form feminine nouns from the following masculine nouns using the

following suffixes: -ess, -ix, -a, -ine.

Actor, host, shepherd, administrator, sultan, lion, prior, negro, hero, prince,

tiger, heir, waiter.

2. Give the corresponding masculine nouns of the following nouns:

queen, woman, daughter, nun, lady, sister, goose, bee, duck, grand-daughter.

3. Give the masculine of: bride, girl-friend, maidservant, female

candidate, policewoman, lady footballer, woman diplomat, lady speaker,

spinster, lady, nurse, female student.

26

4. Translate into English:

1. tiai c premiul a fost din nou cucerit de romni? 2. Este cea mai modern

poet a noastr. 3. Sora mea a jucat rolul prinesei. 4. Ambasadoarea a inut un

discurs. 5. Este o fat btrn foarte excentric. 6. Nu cred c vduva de la

parter este acas. 7. Leoaica pe care ai vzut-o la circ a fost adus din Africa.

8. A venit lptreasa azi? 9. Este plcut cnd eti servit de servitoare aa de

politicoase. 10. Toate miresele sunt frumoase. 11. Prietena fratelui meu are

numai 18 ani. 12. Bunica e mndr de copiii i nepoii ei. 13. Este foarte dificil

s ai de-a face cu astfel de paciente. 14. Toi membrii juriului, att juraii, ct

i juratele, au fost de acord asupra verdictului. 15. Contele i contesele au rang

mai mic dect ducele i ducesa.

REFERENCES

Banta, A. 1978. English and Contrastive Studies, Bucureti, Tipografia

Universitii

Broughton, G. 1990. The Penguin English Grammar A-Z for Advanced

Students, London, Penguin ELT

Crystal, David, 1997. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English language,

CUP

Curme, G., 1966. English Grammar, New York, Barnes and Noble

Gleanu Frnoag, G., Comiel, E., 1992. Gramatica limbii engleze, Ed.

Omegapress, Bucureti

Leech, G. and Svartik, I. 1994. A Communicative Grammar of English,

London, Longman House

Levichi, Leon, 1971. Gramatica limbii engleze, Bucureti, Ed. Didactic i

Pedagogic

Levichi, Leon, 1970. Limba englez contemporan - Morfologia, Bucureti,

Ed. Didactic i Pedagogic

Murphy, R., 1992. English in use, ELOD

Nedelcu, C., 2004, English Grammar, Craiova, Editura Universitaria

Palmer F., 1971. Grammar, Penguin Books

Prlog H., 1995. The English Noun Phrase, Timioara, Hestia Publishing

House

Quirk, R.S. Greenbaum, G. Leech, J. Svartik 1976. A Grammar of

Contemporary English, London, Longman

Thomson, A.J. and Martinet, A.V. 1960, 1997. A Practical English Grammar,

OUP

***, 1996, Oxford English Reference Dictionary, OUP

***, 1999. MacMillan, English Dictionary for Advanced Learners

27

CHAPTER 2

THE ARTICLE

Uniti de nvare :

The Definite article

The Indefinite article

The Zero Article

Obiectivele temei:

nelegerea modurilor de folosire a articlolul hotrt n limba englez.

Diferene fa de limba romn

nelegerea modurilor de folosire a articlolul nehotrt n limba

englez. Diferene fa de limba romn

nelegerea construciilor gramaticale n care articolul nu este folosit

Timpul alocat temei : 2 ore

This class includes article and other parts of speech that can replace the

article before a noun, namely the demonstrative, possessive, indefinite,

interogative and negative adjective (a/the/this/my/each/what the most

important place within the class of determiners. It is used only as a determiner,

unlike the other parts of speech which can be used both as determiners

(determiner noun and as pronouns (stand for nouns).

As the commonest determiner of the noun, the article is used for

marking a definite, indefinite or generic reference to a noun (some articles also

discharge functions borrowed from other types of determiners to which they

are etymologically or grammatically related. The definite article may

discharge the same function as the demonstrative adjective, the indefinite

article those of the numeral ONE, the zero article may discharge the function

of indefinite adjectives such as some. From the point of view of function, there

are three articles in English: the definite, the indefinite and the zero articles.

2.1. The Definite Article

The definite article developed from the demonstrative this/that. The

definite article has the fuction of a demonstrative in those cases in which it is

interchangeable with a demonstrative determiner, with no change of meaning.

Eg. It is just what I want at this time.

Dont do anything of the /this/that kind.

Under the/these circumstances it would be foolish to leave.

The definite article also discharges the function of a demonstrative:

e.g. John the Great, Richard the Lion-Hearted

28

The definite article is invariable in spelling, but pronounced the in

front of words begeinning with a consonant or semivowel and thi before

words beginning with a vowel sound. thi is pronounced when it is stressed.

eg. Jones is the thi specialist in Kindmy trouble.

The definite article can be used with singular and plural nouns.

2.1.1. The functions of the definite article

1. Individual, definite/specific/unique reference (it is a deicitic

reference; deictic=pointing to)

The function of the definite article is to show that the noun to which it is

attached is definite, is known, is particularized in a certain context:

- The preceding context (anaphoric reference)

- The following context (cataphoric reference)

-

a) The anaphoric reference (anaphora= the use of a word) as a substitute

for a previous word or group of words. The noun to which the definite article

is attached by the speaker as being known to the interlocutor, which

(generally speaking) presupposes a previous occurrence of the respective

noun.

(i). The antecedent may be found in the same linguistic context ( in the

same sentence or in a previous sentence).

e.g. I brought a book yesterday. The book seems interesting.

The noun to which the definite article is attached is known because it

has been introduced previously.

(ii). The antecedent may be found in the non-linguistic context.

The definite article is used with nouns whose reference is understood,

therefore is definite in the situational context (of communication).

e.g. a situational context may be: a room. If somebody says: Close the

window.

although the noun window hasnt been mentioned previously, it is

known by the speaker and by the interlocutor, therefore it is definite /unique in

the situational context in which the alternance takes place.

e.g. In a town: the townhall, the police station are definite, unique within

the town that the speaker and intelocutor are in.

On a broader plane, in the world, in the universe, we talk of the sun,

the moon, the earth as unique elements known as a whole.

b) The cataphoric reference: when the definite determination follows the

noun being expressed by a relative clause or a prepositional phrase (again

here the definite article is used on the basis of the linguistic context).

e.g. The book that I brought yesterday seems quite interesting.

The book on the table seems quite interesting.

The post determiners (Relative Clauses, Prepositional Phrases) require definite

articles.

2. Non-significant reference with proper names

Proper names need no articles as they are definite enough in

themselves, the individualization of the nouns is denoted by themselves. In

other words, having unique or individual reference by themselves, proper

29

names are not expected to be used with the definite article, so the presence of

the definite article is logically superfluous.

This use of the definite article can be explained historically: Proper

names were used as adjectives determining a noun:

eg. The Atlantic Ocean

Even when the determined noun (the head) was later omitted, but the

proper name is still preceded by the definite article, the Atlantic.

The other words, the definite article is used with those geographical

names which are still felt as adjectives to which the head may be added.

The definite article is used with the following classes of proper names:

I. geographical names: names of oceans, seas, rivers, mountains ranges,

names of countries, (which certain a common noun such as republic, state);

names of canals, deserts, gulfs, etc.

e.g. The Atlantic (ocean) , The Mediterranean sea, The Danube River, The

USA, The Sahara Desert.

II. names of institutions: hotels, restaurants, threatres, cinema, museum,

libraries.

e.g. The Ritz Hotel, The Atheneum , The British Museum.

III. names of newspapers

e.g. The Times

IV. names of ships

e.g The Titanic

V. Proper names are used with the definite article where they are post-

modified by an attribute or a clause.

e.g. The England of Queen Elizabeth, but Elizabethan England.

I didnt like The Ophelia in the modern version of the play.

The Paris I used to know was more beautiful now than ever.

The plural of Proper name preceded by the definite article denotes a

whole family.

e.g. The Wilsons are going abroad

3. Generic reference

when the noun is used in its general sense, as a representative of a class, as a

whole. The definite article discharges this use before the singular member of

countable nouns.

e.g. The horse is an useful animal.

Lions are animals of prey.

4. Syntactically, the definite article occurs:

- before comparatives and superlatives (adjectives and adverbs)

e.g. The richest (people) are not always the happiest.

- before ordinal numerals

e.g. the fifth lesson.

The more they argued, the angrier they become.

30

- set phrases: in the main, on the one/other hand, to take the trouble, on the

whole, to tell/speech, to be out of question, to be on the safe side, for the time

being in the long run, by the way.

What are the functions of the Definite

Article?

2.2. The Indefinite Article

Developed from the word one, it has 2 forms:

- a used before words beginninig with consonnants or semivowels

- an used before words beginning with vowel sounds: a man, a university, an

egg, an hour.

2.2.1. The functions of the indefinite article

It is used with singular countable nouns.

1. The Indefinite (anticipatory) epiphonic reference.

The typical use of indefinite article is this epiphonic use: a(n)

introduces a new element in the communication when the speaker considers

that noun preceded by the indefinite article is not known to the interlocutor.

e.g. I brought a book yesterday.

I saw a lion at the zoo.

Corresponding to indefinite a used with singular countable nouns in

the indefinite determiner, some used with plural nouns.

e.g. I brought (some) books yesterday. I saw some lions at the zoo.

In such indefinite use it is possible to skip some but not a. The nouns

that are introduced in the speech by the anticipatory a are later referred to by

anaphoric the.

2. The Numeric functions

a) The indefinite article as a weak form of the numeral one is used with

a clear numerical value before countable nouns in the singular indicating

measure or a numerical series.

e.g. Wait a minute!

She was silent for a (one) moment.

A and one are often interchangeable.

b) When used distributively, the indefinite article approaches the

meaning of each/every in expressions of price, speed, radio.

e.g. It costs a penny a pound.

He works 8 hours a day.

His rent is 100 a mouth.

In numeral English, a could be replaced by the prepositions per.

e.g. The brewers use barely approximately 100,000 tens per year.

3. The Generic/classifying function

31

The indefinite article can be used with countable nouns in the singular

to represent a class, of things as a whole (a representative member of a class).

This function is usually formal in definitions

e.g. A lion is a beast of prey.

or in proverbs

e.g. A friend is a friend indeed.

When the indefinite article is used generically it may be considered a

weaker any.

The indefinite use and the generic/classifying use of a(n) may be

distinguished from each other by their different plurals.

Indefinite: I saw a lion - singular

I saw some lions - plural

Generic: A lion is a wild animal.

Lions are wild animals.

Some is used with the plural corresponding to the indefinite a, but with

the plural of generic a.

4. In certain syntactic constructions

a) the indefinite article occurs with nouns in predicative positions (the

predicate) denoting a profession, job, nationality)

e.g. John was/become a teacher.

He is an Englishman.

No article is used when the noun designates a unique representative of a

profession.

e.g. He was elected president of the trade union.

b) in oppositions

e.g. W. Irving, an American prose writer, was born in 1793.

c) after the conjunction as (meaning in the capacity of) .

e.g. He worked there for several years as a designer.

He was often ill as a child.

No article is used if the noun designates a unique profession, rank.

e.g. As chairman, I insist that nobody speak out of terms.

d) after such, quite, rather, what, too, so, how.

e.g. Mary is such a pretty girl! Such a pity!

We had quite a party!

He is rather a fool.

What a pretty girl Mary is!

How perfect a view!

She is too kind a girl to refuse!

We could not do it in so short time.

How /so + adj + a +noun, usually used in the literary style are replaced in

colloquial speech by what and such.

e.g. How astonishing a night What an astonishing night!

So short a time - such a short time.

32

e) The determiner phrase many a followed by a singular noun phrase with

singular agreement has plural meaning (it is rather literary in use): Many

a+Nsg.+Vsg:

e.g. Many a traveller has admired the Danube Delta.

But, the determiner phrase a good/great many is followed by a plural N.P.: A

good great many +Npl+Vpl:

e.g. A good(great) many children were going to the demonstration.

f) The indefinite article can be used with a plural construction expressing a

measure and regarded as a single whole, as it can be seen from the form of the

verb (in the singular).

e.g. We spent a pleasant three days in the country.

The show was performed for another 3 weeks.

5. In set phrases

We have to bear in mind the big difference to Romanian language. In

Romanian most of these set phrases have a article: to be in a hurry, take a

seat, at a distance, to be a pity, to be in a rage, all of a sudden, have a mind to,

take a funny to.

What are the functions of the Indefinite

Article?

2.3. The Zero Article

It occurs with all the categories of nouns, singular and plural, countable

and uncountable nouns.

2.3.1. The functions of zero article are:

1. The generic function/ reference

It is the typical function of the zero article. The zero article is characteristically

a generic determiner in which function it used before:

a) uncountable nouns concrete or abstract nouns

The use of the zero article with such nouns viewed in general is in

opposition with the use of the zero article when referring to a concrete/definite

noun grammatically: when the noun is determined, when it is followed by a

post-modifier, a relative clause, a prepositional phrase.

e.g. Water is necessary to life. (concrete noun)

We have to notice that the use of the zero article before a mass noun:

water is viewed in general, as unlimited material.

The water in the jug is not fresh.

We have to notice that the definite article is required because the post-

modifying phrase in this jug makes the fact that the water refers to a definite

quantity.

e.g. Friendship is a noble feeling. (abstract noun)

The friendship between the two writers lasted long.

33

We have to notice that the definite article is required because the post-

modifing phrase between two writers makes the friendship to have an unique

reference. Other abstract nouns free of articles: nature, society.

e.g. We have duties to society as well as to ourselves.

b) countable nouns:

(i). countable nouns in the plural: plural nouns preceded by the zero article

denote an indefinite number:

e.g. Books are useful to a scholar.

Children like to play.

The some opposition can be established here between the use of the

zero article with the use of the definite article: when a post modifier

construction limits the meaning of the noun to a specify member, the noun is

preceded by the definite article.

e.g. The books for this course are available to any library.

(ii). countable nouns in the singular (man/woman)

e.g. Nature has been changed by man.

Man is an intelligent being.

When the generic use of the articles proves to be syntactically relevant,

the general nouns, the concrete nouns are accompanied by the definite article

while abstract nouns have the zero article.

There is a large category of nouns which are used either with the

definite article or with the zero article depending on whether their meaning

is considered as concrete or abstract (A typical example is school: to go to

school means attend school, while to go to the school means go to the place

where school building is located).