Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Chinese

Încărcat de

Khuong Lam0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

272 vizualizări21 paginirtyytr

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

TXT, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentrtyytr

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca TXT, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

272 vizualizări21 paginiChinese

Încărcat de

Khuong Lamrtyytr

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca TXT, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 21

Chinese language

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the official language of the People's Republic of China, Taiwan, and Singapo

re, see Standard Chinese. For other languages spoken in China, see Languages of

China.

Unless otherwise specified, Chinese texts in this article are written in (Simpli

fied Chinese/Traditional Chinese; Pinyin) format. In cases where Simplified and

Traditional Chinese scripts are identical, the Chinese term is written once.

Chinese

??/?? or ??

Hnyu or Zhongwn

Hanyu trad simp.svg

Hnyu (Chinese) written in traditional (left) and simplified (right) characters

Native to China, Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Macau, Malaysia, the United

States, Canada, Indonesia, Vietnam, and other places with significant overseas

Chinese communities

Ethnicity Han Chinese

Native speakers

unknown (1.2 billion cited 19842000)[1]

Language family

Sino-Tibetan

Sinitic

Chinese

Standard forms

Putonghua (Standard Mandarin)

Dialects

Mandarin

Jin

Wu (incl. Shanghainese)

Huizhou

Gan

Xiang

Min (incl. Teochew, Amoy, Taiwanese)

Hakka

Yue (incl. Cantonese, Taishanese)

Ping

Writing system

Chinese characters, zhuyin fuhao, Latin, Arabic, Cyrillic, braille

Official status

Official language in

China

Hong Kong

Macau

Taiwan

Singapore

Burma Wa State, Burma

United Nations

Recognised minority language in

Canada

Malaysia

United States

Regulated by China National Commission on Language and Script Work[2]

Taiwan National Languages Committee

Singapore Promote Mandarin Council/Speak Mandarin Campaign[3]

Malaysia Chinese Language Standardisation Council

Language codes

ISO 639-1 zh

ISO 639-2 chi (B)

zho (T)

ISO 639-3 zho inclusive code

Individual codes:

cdo Min Dong

cjy Jinyu

cmn Mandarin

cpx Pu Xian

czh Huizhou

czo Min Zhong

gan Gan

hak Hakka

hsn Xiang

mnp Min Bei

nan Min Nan

wuu Wu

yue Yue

och Old Chinese

ltc Late Middle Chinese

lzh Classical Chinese

Linguasphere 79-AAA

Glottolog sini1245[4]

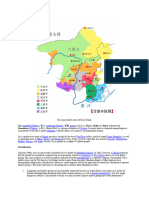

{{{mapalt}}}

Map of the Sinophone world.

Information:

Countries identified Chinese as a primary, administrative, or native language

Countries with more than 5,000,000 Chinese speakers

Countries with more than 1,000,000 Chinese speakers

Countries with more than 500,000 Chinese speakers

Countries with more than 100,000 Chinese speakers

Major Chinese-speaking settlements

This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, yo

u may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters.

Chinese languages (Spoken)

Simplified Chinese ??

Traditional Chinese ??

[show]Transcriptions

Chinese language (Written)

Chinese ??

Literal meaning Chinese text

[show]Transcriptions

This article contains Chinese text. Without proper rendering support, yo

u may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters.

Chinese (?? / ??; Hnyu or ??; Zhongwn) is a group of related language varieties, s

everal of which are not mutually intelligible, and is variously described as a l

anguage or language family.[a] Chinese forms one of the branches of the Sino-Tib

etan language family. Originally the indigenous speech of the Han majority in Ch

ina, it is now spoken by many Chinese ethnic groups. About one-fifth of the worl

d's population, or over one billion people, speaks some form of Chinese as their

first language.

Varieties of Chinese are usually perceived by native speakers as dialects of a s

ingle Chinese language, rather than separate languages, although this identifica

tion is considered inappropriate by some linguists and sinologists.[5] The inter

nal diversity of Chinese has been likened to that of the Romance languages, alth

ough all varieties of Chinese are tonal and analytic. There are between 7 and 13

main regional groups of Chinese (depending on classification scheme), of which

the most spoken, by far, is Mandarin (about 960 million), followed by Wu (80 mil

lion), Yue (60 million) and Min (50 million). Most of these groups are mutually

unintelligible, although some, like Xiang and the Southwest Mandarin dialects, m

ay share common terms and some degree of intelligibility.

Standard Chinese (Putonghua/Guoyu/Huayu) is a standardized form of spoken Chines

e based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin. It is the official language of the P

eople's Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC, also known as Ta

iwan), as well as one of four official languages of Singapore. It is one of the

six official languages of the United Nations. The written form of the standard l

anguage (??; Zhongwn), based on the logograms known as Chinese characters (?? / ?

?; hnzi), is shared by literate speakers of otherwise unintelligible dialects.

Of the other varieties of Chinese, Cantonese (the prestige variety of Yue) is in

fluential in Guangdong province and Cantonese-speaking overseas communities and

remains one of the official languages of Hong Kong (together with English) and o

f Macau (together with Portuguese). Min Nan, part of the Min group, is widely sp

oken in southern Fujian, in neighbouring Taiwan (where it is known as Taiwanese

or Hoklo) and in Southeast Asia (also known as Hokkien in the Philippines, Singa

pore, and Malaysia). There are also sizeable Hakka and Shanghainese diasporas, f

or example in Taiwan, where most Hakka communities are also conversant in Taiwan

ese and Standard Chinese.

Contents [hide]

1 History

2 Influences

3 Varieties of Chinese

3.1 Classification

3.2 Standard Chinese and diglossia

3.3 Nomenclature

4 Writing

4.1 Chinese characters

4.2 Homophones

5 Phonology

5.1 Tones

6 Phonetic transcriptions

6.1 Romanization

6.2 Other phonetic transcriptions

7 Grammar and morphology

8 Vocabulary

9 Loanwords

9.1 Modern borrowings and loanwords

10 Education

11 See also

12 Notes

13 References

14 Further reading

15 External links

History[edit]

Main article: History of the Chinese language

Most linguists classify all the varieties of Chinese language as part of the Sin

o-Tibetan language family and believe that there was an original Proto-Sino-Tibe

tan language from which the Sinitic and Tibeto-Burman languages descended. The r

elation between Chinese and other Sino-Tibetan languages is an area of active re

search, as is the attempt to reconstruct the proto-language. The main difficulty

in this effort is that, while there is enough documentation to allow one to rec

onstruct the ancient Chinese sounds, there is no written documentation that reco

rds the division between Proto-Sino-Tibetan and ancient Chinese. In addition, ma

ny of the older languages that would allow us to reconstruct Proto-Sino-Tibetan

are very poorly understood and many of the techniques developed for analysis of

the descent of the (fusional) Indo-European languages from Proto-Indo-European d

o not apply to Chinese, an analytic language, because of the paucity of inflecti

onal morphemes in modern varieties.[6]

Categorization of the development of Chinese is a subject of scholarly debate.

Old Chinese was the language common during the early and middle Zhou dynasty (10

46256 BCE), texts of which include inscriptions on bronze artifacts, the Classic

of Poetry and portions of the Book of Documents and I Ching. The rhymes of the C

lassic of Poetry and the phonetic elements found in the majority of Chinese char

acters provide hints to their Old Chinese pronunciations. Work on reconstructing

Old Chinese started with Qing dynasty philologists. The first complete reconstr

uction was devised by the Swedish linguist Bernhard Karlgren in the early 1900s;

most present systems rely heavily on Karlgren's insights and methods. Old Chine

se was not wholly uninflected. It possessed a rich sound system in which aspirat

ion and voicing differentiated the consonants, but probably was still without to

nes.

Some early Indo-European loan-words in Chinese have been proposed, notably ? m "h

oney", ? shi "lion," and perhaps also ? ma "horse", ? zhu "pig", ? quan "dog", a

nd ? "goose". Reconstructions of Old Chinese are not definitive, so this hypothe

sis is tentative.[b] The source also notes that southern dialects of Chinese hav

e more monosyllabic words than the Mandarin Chinese dialects.

Middle Chinese was the language used during Southern and Northern Dynasties and

the Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties (6th through 10th centuries CE). It can be div

ided into an early period, reflected by the Qieyun rime book (601 CE), and a lat

e period in the 10th century, reflected by rhyme tables such as the Yunjing cons

tructed by ancient Chinese philologists to summarize the Qieyun system. Linguist

s are more confident of having reconstructed how Middle Chinese sounded. The evi

dence for the pronunciation of Middle Chinese comes from several sources: modern

dialect variations, rhyming dictionaries and tables, foreign transliterations,

and Chinese phonetic translations of foreign words. The pronunciation of the bor

rowed Chinese words in Japanese, Vietnamese and Korean also provide valuable ins

ights.

The development of the spoken Chinese languages from early historical times to t

he present has been complex. Most Chinese people, in Sichuan and in a broad arc

from the north-east (Manchuria) to the south-west (Yunnan), use various Mandarin

dialects as their home language. The prevalence of Mandarin throughout northern

China is largely due to north China's plains. By contrast, the mountains and ri

vers of middle and southern China promoted linguistic diversity.

Until the mid-20th century, most southern Chinese only spoke their native local

variety of Chinese. As Nanjing was the capital during the early Ming dynasty, Na

njing Mandarin became dominant at least until the later years of the Qing dynast

y. Since the 17th century, the Qing dynasty had set up orthoepy academies (????/

????; Zhngyin Shuyun) to make pronunciation conform to the standard of the capital

Beijing. For the general population, however, this had limited effect. The non-

Mandarin speakers in southern China also continued to use their various language

s for every aspect of life. The Beijing Mandarin court standard was used solely

by officials and civil servants and was thus fairly limited.

This situation did not change until the mid-20th century with the creation (in b

oth the PRC and the ROC, but not in Hong Kong) of a compulsory educational syste

m committed to teaching Mandarin. As a result, Mandarin is now spoken by virtual

ly all young and middle-aged citizens of mainland China and on Taiwan. Cantonese

, not Mandarin, was used in Hong Kong during the time of its British colonial pe

riod (owing to its large Cantonese native and migrant populace) and remains toda

y its official language of education, formal speech, and daily life, but Mandari

n has become increasingly influential since the 1997 handover.

The term sinophone, coined in 2005 in analogy to anglophone and francophone, ref

ers to those who speak at least one Chinese language natively, or prefer it as a

medium of communication. The term is derived from Sinae, the Latin word for anc

ient China.[c]

Influences[edit]

See also: Adoption of Chinese literary culture and Sino-Xenic vocabularies

The Tripitaka Koreana, a Korean collection of the Chinese Buddhist canon

The Chinese language has spread to neighbouring countries through a variety of m

eans. Northern Vietnam was incorporated into the Han empire in 111 BCE, beginnin

g a period of Chinese control that ran almost continuously for a millennium. The

Four Commanderies were established in northern Korea in the first century BCE,

but disintegrated in the following centuries.[7] Chinese Buddhism spread over Ea

st Asia between the 2nd and 5th centuries CE, and with it the study of scripture

s and literature in Literary Chinese.[8] Later Korea, Japan and Vietnam develope

d strong central governments modelled on Chinese institutions, with Literary Chi

nese as the language of administration and scholarship, a position it would reta

in until the late 19th century in Korea and (to a lesser extent) Japan, and the

early 20th century in Vietnam.[9] Scholars from different lands could communicat

e, albeit only in writing, using Literary Chinese.[10]

Although they used Chinese solely for written communication, each country had it

s own tradition of reading texts aloud, the so-called Sino-Xenic pronunciations.

Chinese words with these pronunciations were also borrowed extensively into the

Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese languages, and today comprise over half their v

ocabularies.[11] This massive influx led to changes in the phonological structur

e of the languages, contributing to the development of moraic structure in Japan

ese[12] and the disruption of vowel harmony in Korean.[13]

Borrowed Chinese morphemes have been used extensively in all these languages to

coin compound words for new concepts, in a similar way to the use of Latin and A

ncient Greek roots in European languages.[14] Many new compounds, or new meaning

s for old phrases, were created in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to nam

e Western concepts and artifacts. These coinages, written in shared Chinese char

acters, have then been borrowed freely between languages. They have even been ac

cepted into Chinese, a language usually resistant to loanwords, because their fo

reign origin was hidden by their written form. Often different compounds for the

same concept were in circulation for some time before a winner emerged, and som

etimes the final choice differed between countries.[15] The proportion of vocabu

lary of Chinese origin thus tends to be greater in technical, abstract or formal

language. For example, Sino-Japanese words account for about 35% of the words i

n entertainment magazines, over half the words in newspapers, and 60% of the wor

ds in science magazines.[16]

Vietnam, Korea and Japan each developed writing systems for their own languages,

initially based on Chinese characters, but later replaced with the Hangul alpha

bet for Korean and supplemented with kana syllabaries for Japanese, while Vietna

mese continued to be written with the complex Ch? nm script. However these were l

imited to popular literature until the late 19th century. Today Japanese is writ

ten with a composite script using both Chinese characters (Kanji) and kana, but

Korean is written exclusively with Hangul in North Korea, and supplementary Chin

ese characters (Hanja) are increasingly rarely used in the South. Vietnamese is

written with a Latin-based alphabet.

Examples of loan words in English include "tea", from Minnan t (?) and "kumquat",

from Cantonese gam1gwat1 (??).

Varieties of Chinese[edit]

Main article: Varieties of Chinese

Jerry Norman estimated that there are hundreds of mutually unintelligible variet

ies of Chinese.[17] These varieties form a dialect continuum, in which differenc

es in speech generally become more pronounced as distances increase, though the

rate of change varies immensely.[18] Generally, mountainous South China displays

more linguistic diversity than the North China Plain. In parts of South China,

a major city's dialect may only be marginally intelligible to close neighbours.

For instance, Wuzhou is about 120 miles upstream from Guangzhou, but its dialect

is more like that of Guangzhou than is that of Taishan, 60 miles southwest of G

uangzhou and separated from it by several rivers.[19] In parts of Fujian the spe

ech of neighbouring counties or even villages may be mutually unintelligible.[20

]

Classification[edit]

Local varieties of Chinese are conventionally classified into seven dialect grou

ps, largely on the basis of the different evolution of Middle Chinese voiced ini

tials:[21][22]

Mandarin, including Standard Chinese

Wu, including Shanghainese

Gan

Xiang

Min, including Hokkien, Taiwanese and Teochew

Hakka

Yue, including Cantonese and Taishanese

The classification of Li Rong, which is used in the Language Atlas of China (198

7), distinguishes three further groups:[23][24]

Jin, previously included in Mandarin.

Huizhou, previously included in Wu.

Pinghua, previously included in Yue.

The primary branches of Chinese in eastern China and Taiwan[23]

Numbers of first-language speakers (all countries):[25]

Circle frame.svg

Mandarin: 847.8 million (70.9%)

Jin: 45 million (3.8%)

Wu: 77.2 million (6.5%)

Huizhou: 4.6 million (0.4%)

Gan: 20.6 million (1.7%)

Xiang: 36 million (3.0%)

Min: 71.8 million (6.0%)

Hakka: 30.1 million (2.5%)

Yue and Pinghua: 62.2 million (5.2%)

Some varieties remain unclassified, including Danzhou dialect (spoken in Danzhou

, on Hainan Island), Xianghua (spoken in western Hunan) and Shaozhou Tuhua (spok

en in northern Guangdong).[26] The Dungan language, spoken in Central Asia, is a

Mandarin variety, but is politically not generally considered "Chinese" since i

t is written in Cyrillic and spoken by Dungan people outside China who are not c

onsidered ethnic Chinese.

Standard Chinese and diglossia[edit]

Main articles: Standard Chinese and List of countries where Chinese is an offici

al language

Putonghua / Guoyu, often called "Mandarin", is the official standard language us

ed by the People's Republic of China, the Republic of China (Taiwan), and Singap

ore (where it is called "Huayu" or simply Chinese). It is based on the Beijing d

ialect, which is the dialect of Mandarin as spoken in Beijing. The government in

tends for speakers of all Chinese speech varieties to use it as a common languag

e of communication. Therefore it is used in government agencies, in the media, a

nd as a language of instruction in schools.

In mainland China and Taiwan, diglossia has been a common feature: it is common

for a Chinese to be able to speak two or even three varieties of the Sinitic lan

guages (or "dialects") together with Standard Chinese. For example, in addition

to putonghua, a resident of Shanghai might speak Shanghainese; and, if he or she

grew up elsewhere, then he or she may also be likely to be fluent in the partic

ular dialect of that local area. A native of Guangzhou may speak both Cantonese

and putonghua, a resident of Taiwan, both Taiwanese and putonghua/guoyu. A perso

n living in Taiwan may commonly mix pronunciations, phrases, and words from Mand

arin and Taiwanese, and this mixture is considered normal in daily or informal s

peech.

Nomenclature[edit]

In common English usage, Chinese is considered a language and its varieties "dia

lects", a classification that agrees with Chinese speakers' self-perception. Mos

t linguists prefer instead to call Chinese a family of languages, because of the

lack of mutual intelligibility between its divisions. Measuring this mutual int

elligibility is not precise, but Chinese is often compared to the Romance langua

ges in this regard. Some linguists find the use of "Chinese languages" also prob

lematic, because it can imply a set of disruptive "religious, economic, politica

l, and other differences" between speakers that exist between for example betwee

n French Catholics and English Protestants in Canada, but not between speakers o

f Cantonese and Mandarin in China, owing to China's near-uninterrupted history o

f centralized government.[27]

Chinese itself has a term for its unified writing system, Zhongwn (??), while the

closest equivalent used to describe its spoken variants would be Hnyu (??/??, "s

poken language[s] of the Han Chinese")this term could be translated to either "la

nguage" or "languages" since Chinese lacks grammatical number. For centuries in

China, owing to the widespread use of a written standard in Classical Chinese, t

here was no uniform speech-and-writing continuum, as indicated by the employment

of two separate morphemes yu ?/? and wn ?. The characters used in written Chines

e are logographs that denote morphemes as a whole rather than their phonemes, al

though most logographs are compounds of similar-sounding characters and semantic

disambiguation (the "radical"). Modern-day Chinese speakers of all kinds commun

icate using the modern standard written language, the written form of Standard C

hinese.

In Chinese, the major spoken varieties of Chinese are called fangyn (??, literall

y "regional speech"), and mutually intelligible variants within these are called

ddian fangyn (????/???? "local speech"). Both terms are customarily translated in

to English as "dialect".[27] Ethnic Chinese often consider these spoken variatio

ns as one single language for reasons of nationality and as they inherit one com

mon cultural and linguistic heritage in Classical Chinese. Han native speakers o

f Wu, Min, Hakka, and Cantonese, for instance, may consider their own linguistic

varieties as separate spoken languages, but the Han Chinese as onealbeit interna

lly very diverseethnicity. To Chinese nationalists, the idea of Chinese as a lang

uage family may suggest that the Chinese identity is much more fragmented and di

sunified than it actually is and as such is often looked upon as culturally and

politically provocative. Additionally, in Taiwan it is closely associated with T

aiwanese independence, some of whose supporters promote the local Taiwanese Minn

an-based spoken language.

Writing[edit]

Main articles: Written Chinese, Mainland Chinese Braille and Taiwanese Braille

The relationship between the Chinese spoken and written language is rather compl

ex. Its spoken varieties evolved at different rates, while written Chinese itsel

f has changed much less. Classical Chinese literature began in the Spring and Au

tumn period, although written records have been discovered as far back as the 14

th to 11th centuries BCE Shang dynasty oracle bones using the oracle bone script

s.

The Chinese orthography centers on Chinese characters, hanzi, which are written

within imaginary rectangular blocks, traditionally arranged in vertical columns,

read from top to bottom down a column, and right to left across columns. Chines

e characters are morphemes independent of phonetic change. Thus the character ?

("one") is uttered yi/yao in Standard Chinese, jat1 in Cantonese and chi?t/it in

Hokkien (form of Min). Vocabularies from different major Chinese variants have

diverged, and colloquial non-standard written Chinese often makes use of unique

"dialectal characters", such as ? and ? for Cantonese and Hakka, which are consi

dered archaic or unused in standard written Chinese.

Written colloquial Cantonese has become quite popular in online chat rooms and i

nstant messaging amongst Hong-Kongers and Cantonese-speakers elsewhere. Use of i

t is considered highly informal, and does not extend to many formal occasions.

In Hunan, women in certain areas write their local language in N Shu, a syllabary

derived from Chinese characters. The Dungan language, considered by many a dial

ect of Mandarin, is nowadays written in Cyrillic, and was previously written in

the Arabic script. The Dungan people are primarily Muslim and live mainly in Kaz

akhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia; some of the related Hui people also speak the l

anguage and live mainly in China.

Chinese characters[edit]

Main article: Chinese character

"Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion" by Wang Xizhi, written in

semi-cursive style

Each Chinese character represents a monosyllabic Chinese word or morpheme. In 10

0 CE, the famed Han dynasty scholar Xu Shen classified characters into six categ

ories, namely pictographs, simple ideographs, compound ideographs, phonetic loan

s, phonetic compounds and derivative characters. Of these, only 4% were categori

zed as pictographs, including many of the simplest characters, such as rn ? (huma

n), r ? (sun), shan ? (mountain; hill), shui ? (water). Between 80% and 90% were

classified as phonetic compounds such as chong ? (pour), combining a phonetic co

mponent zhong ? (middle) with a semantic radical ? (water). Almost all character

s created since have been of this type. The 18th-century Kangxi Dictionary recog

nized 214 radicals.

Modern characters are styled after the regular script. Various other written sty

les are also used in Chinese calligraphy, including seal script, cursive script

and clerical script. Calligraphy artists can write in traditional and simplified

characters, but they tend to use traditional characters for traditional art.

There are currently two systems for Chinese characters. The traditional system,

still used in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macau and Chinese speaking communities (except

Singapore and Malaysia) outside mainland China, takes its form from standardized

character forms dating back to the late Han dynasty. The Simplified Chinese cha

racter system, developed by the People's Republic of China in 1954 to promote ma

ss literacy, simplifies most complex traditional glyphs to fewer strokes, many t

o common cursive shorthand variants.

Singapore, which has a large Chinese community, is the firstand at present the on

lyforeign nation to officially adopt simplified characters, although it has also

become the de facto standard for younger ethnic Chinese in Malaysia. The Interne

t provides the platform to practice reading the alternative system, be it tradit

ional or simplified.

A well-educated Chinese reader today recognizes approximately 4,0006,000 characte

rs; approximately 3,000 characters are required to read a Mainland newspaper. Th

e PRC government defines literacy amongst workers as a knowledge of 2,000 charac

ters, though this would be only functional literacy. A large unabridged dictiona

ry, like the Kangxi Dictionary, contains over 40,000 characters, including obscu

re, variant, rare, and archaic characters; fewer than a quarter of these charact

ers are now commonly used.

Homophones[edit]

Standard Chinese has fewer than 1,700 distinct syllables but 4,000 common writte

n characters, so there are many homophones. For example, the following character

s (not necessarily words) are all pronounced ji: ?/? chicken, ?/? machine, ? bas

ic, ?/? to hit, ?/? hunger, and ?/? accumulate. In speech, the meaning of a syll

able is determined by context (for example, in English, "some" as the opposite o

f "none" as opposed to "sum" in arithmetic) or by the word it is found in ("some

" or "sum" vs. "summer"). Speakers may clarify which written character they mean

by giving a word or phrase it is found in: ?????,?????,???? Mngzi jio Jiaying, Ji

alng Jiang de jia, Yinggu de ying "My name is Jiaying, 'Jia' as in 'Jialing River'

and 'ying' as in 'England'."

Southern Chinese varieties like Cantonese and Hakka preserved more of the rimes

of Middle Chinese and also have more tones. Several of the examples of Mandarin

ji above have distinct pronunciations in Cantonese (romanized using jyutping): g

ai1, gei1, gei1, gik1, gei1, and zik1 respectively. For this reason, southern va

rieties tend to need to employ fewer multi-syllabic words.

Phonology[edit]

See also: Standard Chinese phonology, Historical Chinese phonology and Varieties

of Chinese

The phonological structure of each syllable consists of a nucleus consisting of

a vowel (which can be a monophthong, diphthong, or even a triphthong in certain

varieties), preceded by an onset (a single consonant, or consonant+glide; zero o

nset is also possible), and followed (optionally) by a coda consonant; a syllabl

e also carries a tone. There are some instances where a vowel is not used as a n

ucleus. An example of this is in Cantonese, where the nasal sonorant consonants

/m/ and /?/ can stand alone as their own syllable.

Across all the spoken varieties, most syllables tend to be open syllables, meani

ng they have no coda (assuming that a final glide is not analyzed as a coda), bu

t syllables that do have codas are restricted to /m/, /n/, /?/, /p/, /??/, /t/,

/k/, or /?/. Some varieties allow most of these codas, whereas others, such as S

tandard Chinese, are limited to only /n/, /?/ and /??/.

The number of sounds in the different spoken dialects varies, but in general the

re has been a tendency to a reduction in sounds from Middle Chinese. The Mandari

n dialects in particular have experienced a dramatic decrease in sounds and so h

ave far more multisyllabic words than most other spoken varieties. The total num

ber of syllables in some varieties is therefore only about a thousand, including

tonal variation, which is only about an eighth as many as English.[d]

Tones[edit]

All varieties of spoken Chinese use tones. A few dialects of north China may hav

e as few as three tones, while some dialects in south China have up to 6 or 10 t

ones, depending on how one counts. One exception from this is Shanghainese which

has reduced the set of tones to a two-toned pitch accent system much like moder

n Japanese.

A very common example used to illustrate the use of tones in Chinese are the fou

r tones of Standard Chinese (along with the neutral tone) applied to the syllabl

e ma. The tones are exemplified by the following five Chinese words:

The four main tones of Standard Mandarin pronounced with the syllable 'ma':

MENU0:00

Example of Standard Mandarin tones

Hanzi Pinyin Pitch contour Meaning

?/? ma high level "mother"

? m high rising "hemp"

?/? ma low falling-rising "horse"

?/? m high falling "scold"

?/? ma neutral question particle

Standard Cantonese, by contrast, has nine different tones:[28]

Example of Standard Cantonese tones

Hanzi Jyutping Pitch contour Meaning

?/ ? si1 ?? - High level 'poem

? si2 ?? - High rising history

? si3 ?? - Mid level to assassinate

?/? si4 ?? - Mid-low falling time

? si5 ?? - Mid-low rising market

? si6 ?? - Mid-low level yes

? si7 ?? - High stopped color

? si8 ?? - Mid stopped thorn

? si9 ?? - Mid-low stopped to eat

Phonetic transcriptions[edit]

The Chinese had no uniform phonetic transcription system until the mid-20th cent

ury, although enunciation patterns were recorded in early rime books and diction

aries. Early Indian translators, working in Sanskrit and Pali, were the first to

attempt to describe the sounds and enunciation patterns of Chinese in a foreign

language. After the 15th century, the efforts of Jesuits and Western court miss

ionaries resulted in some rudimentary Latin transcription systems, based on the

Nanjing Mandarin dialect.

Romanization[edit]

"National language" (??; Guyu) written in Traditional and Simplified Chinese char

acters, followed by various romanizations.

See also: Chinese language romanisation in Singapore and Romanization of Mandari

n Chinese

Romanization is the process of transcribing a language into the Latin script. Th

ere are many systems of romanization for the Chinese languages due to the lack o

f a native phonetic transcription until modern times. Chinese is first known to

have been written in Latin characters by Western Christian missionaries in the 1

6th century.

Today the most common romanization standard for Standard Chinese is Hanyu Pinyin

, often known simply as pinyin, introduced in 1956 by the People's Republic of C

hina, and later adopted by Singapore and Taiwan. Pinyin is almost universally em

ployed now for teaching standard spoken Chinese in schools and universities acro

ss America, Australia and Europe. Chinese parents also use Pinyin to teach their

children the sounds and tones of new words. In school books that teach Chinese,

the Pinyin romanization is often shown below a picture of the thing the word re

presents, with the Chinese character alongside.

The second-most common romanization system, the WadeGiles, was invented by Thomas

Wade in 1859 and modified by Herbert Giles in 1892. As this system approximates

the phonology of Mandarin Chinese into English consonants and vowels, i.e. it i

s an Anglicization, it may be particularly helpful for beginner Chinese speakers

of an English-speaking background. WadeGiles was found in academic use in the Un

ited States, particularly before the 1980s, and until recently[when?] was widely

used in Taiwan.

When used within European texts, the tone transcriptions in both pinyin and WadeG

iles are often left out for simplicity; WadeGiles' extensive use of apostrophes i

s also usually omitted. Thus, most Western readers will be much more familiar wi

th Beijing than they will be with Beijing (pinyin), and with Taipei than T'ai-pei

(WadeGiles). This simplification presents syllables as homophones which really ar

e none, and therefore exaggerates the number of homophones almost by a factor of

four.

Here are a few examples of Hanyu Pinyin and WadeGiles, for comparison:

Mandarin Romanization Comparison

Characters WadeGiles Hanyu Pinyin Notes

??/?? Chung-kuo Zhonggu "China"

?? Pei-ching Beijing Capital of the People's Republic of China

??/?? T'ai-pei Tibei Capital of the Republic of China (Taiwan)

???/??? Mao Tse-tung Mo Zdong Former Communist Chinese leader

???/??? Chiang Chieh4-shih Jiang Jish Former Nationalist Chinese leade

r (better known to English speakers as Chiang Kai-shek, with Cantonese pronuncia

tion)

?? K'ung Tsu Kong Zi "Confucius"

Other systems of romanization for Chinese include Gwoyeu Romatzyh, the French EF

EO, the Yale (invented during WWII for U.S. troops), as well as separate systems

for Cantonese, Minnan, Hakka, and other Chinese languages or dialects.

Other phonetic transcriptions[edit]

Chinese languages have been phonetically transcribed into many other writing sys

tems over the centuries. The 'Phags-pa script, for example, has been very helpfu

l in reconstructing the pronunciations of pre-modern forms of Chinese.

Zhuyin (also called bopomofo), a semi-syllabary is still widely used in Taiwan's

elementary schools to aid standard pronunciation. Although bopomofo characters

are reminiscent of katakana script, there is no source to substantiate the claim

that Katakana was the basis for the zhuyin system. A comparison table of zhuyin

to pinyin exists in the zhuyin article. Syllables based on pinyin and zhuyin ca

n also be compared by looking at the following articles:

Pinyin table

Zhuyin table

There are also at least two systems of cyrillization for Chinese. The most wides

pread is the Palladius system.

Grammar and morphology[edit]

Main article: Chinese grammar

See also: Chinese classifiers

Chinese is often described as a "monosyllabic" language. However, this is only p

artially correct. It is largely accurate when describing Classical Chinese and M

iddle Chinese; in Classical Chinese, for example, perhaps 90% of words correspon

d to a single syllable and a single character. In the modern varieties, it is st

ill usually the case that a morpheme (unit of meaning) is a single syllable; con

trast English, with plenty of multi-syllable morphemes, both bound and free, suc

h as "seven", "elephant", "para-" and "-able". Some of the conservative southern

varieties of modern Chinese still have largely monosyllabic words, especially a

mong the more basic vocabulary.

In modern Mandarin, however, most nouns, adjectives and verbs are largely disyll

abic. A significant cause of this is phonological attrition. Sound change over t

ime has steadily reduced the number of possible syllables. In modern Mandarin, t

here are now only about 1,200 possible syllables, including tonal distinctions,

compared with about 5,000 in Vietnamese (still largely monosyllabic) and over 8,

000 in English.[d]

This phonological collapse has led to a corresponding increase in the number of

homophones. As an example, the small Langenscheidt Pocket Chinese Dictionary[29]

lists six common words pronounced sh (tone 2): ? "ten"; ? "real, actual"; ? "kno

w (a person), recognize"; ? "stone"; ? "time"; ? "food". These were all pronounc

ed differently in Early Middle Chinese; in William H. Baxter's transcription the

y were dzyip, zyit, syik, dzyek, dzyi and zyik respectively. In modern spoken Ma

ndarin, however, tremendous ambiguity would result if all of these words could b

e used as-is, and so most of them have been replaced (in speech, if not in writi

ng) with a longer, less-ambiguous compound. Only the first one, ? "ten", normall

y appears as such when spoken; the rest are normally replaced with, respectively

, ?? shj (lit. "actual-connection"); ?? rnshi (lit. "recognize-know"); ?? shtou (lit

. "stone-head"); ?? shjian (lit. "time-interval"); ?? shw (lit. "food-thing"). In e

ach case, the homophone was disambiguated by adding another morpheme, typically

either a synonym or a generic word of some sort (for example, "head", "thing"),

whose purpose is simply to indicate which of the possible meanings of the other,

homophonic syllable should be selected.

However, when one of the above words forms part of a compound, the disambiguatin

g syllable is generally dropped and the resulting word is still disyllabic. For

example, ? sh alone, not ?? shtou, appears in compounds meaning "stone-", for exam

ple, ?? shgao "plaster" (lit. "stone cream"), ?? shhui "lime" (lit. "stone dust"),

?? shku "grotto" (lit. "stone cave"), ?? shying "quartz" (lit. "stone flower"), ?

? shyu "petroleum" (lit. "stone oil").

Most modern varieties of Chinese have the tendency to form new words through dis

yllabic, trisyllabic and tetra-character compounds. In some cases, monosyllabic

words have become disyllabic without compounding, as in ?? kulong from ? kong; t

his is especially common in Jin.

Chinese morphology is strictly bound to a set number of syllables with a fairly

rigid construction which are the morphemes, the smallest blocks of the language.

While many of these single-syllable morphemes (?, z) can stand alone as individu

al words, they more often than not form multi-syllabic compounds, known as c (?/?

), which more closely resembles the traditional Western notion of a word. A Chin

ese c (word) can consist of more than one character-morpheme, usually two, but ther

e can be three or more.

For example:

yn ?/? "cloud"

hnbaobao, hnbao ???/???, ??/?? "hamburger"

wo ? "I, me"

rn ? "people"

dqi ?? "earth"

shandin ??/?? "lightning"

mng ?/? "dream"

All varieties of modern Chinese are analytic languages, in that they depend on s

yntax (word order and sentence structure) rather than morphologyi.e., changes in

form of a wordto indicate the word's function in a sentence. In other words, Chin

ese has very few grammatical inflectionsit possesses no tenses, no voices, no num

bers (singular, plural; though there are plural markers, for example for persona

l pronouns), and only a few articles (i.e., equivalents to "the, a, an" in Engli

sh). There is, however, a gender difference in the written language (? as "he" a

nd ? as "she"), but it should be noted that this is a relatively new introductio

n to the Chinese language in the twentieth century, and both characters are pron

ounced in exactly the same way.

They make heavy use of grammatical particles to indicate aspect and mood. In Man

darin Chinese, this involves the use of particles like le ? (perfective), hi ?/?

(still), yijing ??/?? (already), and so on.

Chinese features a subjectverbobject word order, and like many other languages in

East Asia, makes frequent use of the topiccomment construction to form sentences.

Chinese also has an extensive system of classifiers and measure words, another

trait shared with neighbouring languages like Japanese and Korean. Other notable

grammatical features common to all the spoken varieties of Chinese include the

use of serial verb construction, pronoun dropping and the related subject droppi

ng.

Although the grammars of the spoken varieties share many traits, they do possess

differences.

Vocabulary[edit]

The entire Chinese character corpus since antiquity comprises well over 20,000 c

haracters, of which only roughly 10,000 are now commonly in use. However Chinese

characters should not be confused with Chinese words; since most Chinese words

are made up of two or more different characters, there are many times more Chine

se words than there are characters.

Estimates of the total number of Chinese words and phrases vary greatly. The Han

yu Da Zidian, a compendium of Chinese characters, includes 54,678 head entries f

or characters, including bone oracle versions. The Zhonghua Zihai (1994) contain

s 85,568 head entries for character definitions, and is the largest reference wo

rk based purely on character and its literary variants. The CC-CEDICT project (2

010) contains 97,404 contemporary entries including idioms, technology terms and

names of political figures, businesses and products. The 2009 version of the We

bster's Digital Chinese Dictionary (WDCD),[30] based on CC-CEDICT, contains over

84,000 entries.

The most comprehensive pure linguistic Chinese-language dictionary, the 12-volum

ed Hanyu Da Cidian, records more than 23,000 head Chinese characters and gives o

ver 370,000 definitions. The 1999 revised Cihai, a multi-volume encyclopedic dic

tionary reference work, gives 122,836 vocabulary entry definitions under 19,485

Chinese characters, including proper names, phrases and common zoological, geogr

aphical, sociological, scientific and technical terms.

The latest 2012 6th edition of Xiandai Hanyu Cidian, an authoritative one-volume

dictionary on modern standard Chinese language as used in mainland China, has 6

9,000 entries and defines 13,000 head characters.

Loanwords[edit]

See also: Translation of neologisms into Chinese and Transcription into Chinese

characters

Like any other language, Chinese has absorbed a sizable number of loanwords from

other cultures. Most Chinese words are formed out of native Chinese morphemes,

including words describing imported objects and ideas. However, direct phonetic

borrowing of foreign words has gone on since ancient times.

Ancient words borrowed from along the Silk Road since Old Chinese include ?? "gr

ape", ?? "pomegranate" and ??/?? "lion". Some words were borrowed from Buddhist

scriptures, including ? "Buddha" and ??/?? "bodhisattva." Other words came from

nomadic peoples to the north, such as ?? "hutong". Words borrowed from the peopl

es along the Silk Road, such as ?? "grape" (pto in Mandarin) generally have Persia

n etymologies. Buddhist terminology is generally derived from Sanskrit or Pali,

the liturgical languages of North India. Words borrowed from the nomadic tribes

of the Gobi, Mongolian or northeast regions generally have Altaic etymologies, s

uch as ?? "ppa", the Chinese lute, or ? "cheese" or "yoghurt", but from exactly w

hich source is not always clear.[31]

Modern borrowings and loanwords[edit]

Modern neologisms are primarily translated into Chinese in one of three ways: fr

ee translation (calque, or by meaning), phonetic translation (by sound), or a co

mbination of the two. Today, it is much more common to use existing Chinese morp

hemes to coin new words in order to represent imported concepts, such as technic

al expressions and international scientific vocabulary. Any Latin or Greek etymo

logies are dropped and converted into the corresponding Chinese characters (for

example, anti- typically becomes "?", literally opposite), making them more comp

rehensible for Chinese but introducing more difficulties in understanding foreig

n texts. For example, the word telephone was loaned phonetically as ???/??? (Sha

nghainese: tlfon [t?l?fo?], Mandarin: dlufeng) during the 1920s and widely used in

Shanghai, but later ??/?? dinhu (lit. "electric speech"), built out of native Chin

ese morphemes, became prevalent (?? is in fact from Japanese, where it is pronou

nced denwa; see below for more). Other examples include ??/?? dinsh (lit. "electri

c vision") for television, ??/?? dinnao (lit. "electric brain") for computer; ??/

?? shouji (lit. "hand machine") for mobile phone, ??/?? lny (lit. "blue tooth") fo

r Bluetooth, and ??/?? wangzh (lit. "internet logbook") for blog in Hong Kong and

Macau Cantonese. Occasionally half-transliteration, half-translation compromise

s (phono-semantic matching) are accepted, such as ???/??? hnbaobao (lit. "hamburg

bun") for "hamburger". Sometimes translations are designed so that they sound l

ike the original while incorporating Chinese morphemes, such as ???/??? tuolaji

"tractor" (lit. "dragging-pulling machine"), or ???/??? malo for the video game ch

aracter Mario. This is often done for commercial purposes, for example ??/?? ben

tng (lit. "dashing-leaping") for Pentium and ???/??? Sibaiwi (lit. "better-than hun

dred tastes") for Subway restaurants.

Foreign words, mainly proper nouns, continue to enter the Chinese language by tr

anscription according to their pronunciations. This is done by employing Chinese

characters with similar pronunciations. For example, "Israel" becomes ??? yisli,

"Paris" becomes ?? bal. A rather small number of direct transliterations have sur

vived as common words, including ??/?? shafa "sofa", ??/?? mad "motor", ?? youm "h

umor", ??/?? luj "logic", ??/?? shmo "smart, fashionable", and ???? xiesidili "hyste

rics". The bulk of these words were originally coined in the Shanghai dialect du

ring the early 20th century and were later loaned into Mandarin, hence their pro

nunciations in Mandarin may be quite off from the English. For example, ??/?? "s

ofa" and ??/?? "motor" in Shanghainese sound more like their English counterpart

s.

Western foreign words representing Western concepts have influenced Chinese sinc

e the 20th century through transcription. From French came ?? bali "ballet", ?? x

iangbin, "champagne", and from Italian ?? kafei "caff". English influence is part

icularly pronounced. From early 20th century Shanghainese, many English words ar

e borrowed, such as ???/??? gaoerfu "golf" and the above-mentioned ??/?? shafa "

sofa". Later United States soft influences gave rise to ??? dsik "disco", ??/?? ke

l "cola", and ?? mni "mini [skirt]". Contemporary colloquial Cantonese has distinc

t loanwords from English, such as ?? "cartoon", ?? "gay people", ?? "taxi", and

?? "bus". With the rising popularity of the Internet, there is a current vogue i

n China for coining English transliterations, for example, ??/?? fensi "fans", ?

? heik "hacker" (lit. "black guest"), ??? bluog "blog" (lit. "interconnected tribes

") in Taiwanese Mandarin.

Another result of the English influence on Chinese is the appearance in Modern C

hinese texts of so-called ??? zmuc (lit. "lettered words") spelled with letters fr

om foreign alphabets. This has appeared in magazines, newspapers, on web sites,

and on TV: ?G?? "3rd generation cell phones" (? san "three" + G "generation" + ?

? shouji "mobile phones"), IT? "IT industry", HSK (hnyu shuipng kaosh, ??????), GB

(gubiao, ??), CIF? (Cost, Insurance, Freight + ? ji "price"), e?? "electronic home

" (?? jiating "home"), W?? "wireless generation" (?? shdi "generation"), ??call, T

V?, ????? "post-PC era" (? hu "after/post-" + PC "personal computer" + ?? shdi "epo

ch"), and so on.

Since the 20th century, another source of words has been Japanese using existing

kanji (Chinese characters used in Japanese). Japanese re-molded European concep

ts and inventions into wasei-kango (????, lit. "Japanese-made Chinese"), and man

y of these words have been re-loaned into modern Chinese. Other terms were coine

d by the Japanese by giving new senses to existing Chinese terms or by referring

to expressions used in classical Chinese literature. For example, jingj (??/??,

keizai), which in the original Chinese meant "the workings of the state", was na

rrowed to "economy" in Japanese; this narrowed definition was then re-imported i

nto Chinese. As a result, these terms are virtually indistinguishable from nativ

e Chinese words: indeed, there is some dispute over some of these terms as to wh

ether the Japanese or Chinese coined them first. As a result of this loaning, Ch

inese, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese share a corpus of linguistic terms descr

ibing modern terminology, paralleling the similar corpus of terms built from Gre

co-Latin and shared among European languages.

Education[edit]

See also: Chinese as a foreign language

With the growing importance and influence of China's economy globally, Mandarin

instruction is gaining popularity in schools in the USA, and has become an incre

asingly popular subject of study amongst the young in the Western world, as in t

he UK.[32]

In 1991 there were 2,000 foreign learners taking China's official Chinese Profic

iency Test (comparable to the English Cambridge Certificate), while in 2005, the

number of candidates had risen sharply to 117,660.[33] By 2010, 750,000 people

had taken the Chinese Proficiency Test.

See also[edit]

Portal icon China portal

Portal icon Language portal

Chinese exclamative particles

Chinese honorifics

Chinese numerals

Chinese punctuation

Classical Chinese grammar

Four-character idiom

Han unification

Languages of China

North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics

Notes[edit]

Jump up ^ Several authors note that Chinese varieties are as diverse as a family

of languages:

David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ

ersity Press, 1987), p. 312. "The mutual unintelligibility of the varieties is t

he main ground for referring to them as separate languages."

Charles N. Li, Sandra A. Thompson. Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Gram

mar (1989), p. 2. "The Chinese language family is genetically classified as an i

ndependent branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family."

Norman (1988), p. 1. "[...] the modern Chinese dialects are really more like a f

amily of languages [...]"

DeFrancis (1984), p. 56. "To call Chinese a single language composed of dialects

with varying degrees of difference is to mislead by minimizing disparities that

according to Chao are as great as those between English and Dutch. To call Chin

ese a family of languages is to suggest extralinguistic differences that in fact

do not exist and to overlook the unique linguistic situation that exists in Chi

na."

Jump up ^ Encyclopdia Britannica s.v. "Chinese languages": "Old Chinese vocabular

y already contained many words not generally occurring in the other Sino-Tibetan

languages. The words for 'honey' and 'lion', and probably also 'horse', 'dog',

and 'goose', are connected with Indo-European and were acquired through trade an

d early contacts. (The nearest known Indo-European languages were Tocharian and

Sogdian, a middle Iranian language.) A number of words have Austroasiatic cognat

es and point to early contacts with the ancestral language of MuongVietnamese and

MonKhmer"; Jan Ulenbrook, Einige bereinstimmungen zwischen dem Chinesischen und d

em Indogermanischen (1967) proposes 57 items; see also Tsung-tung Chang, 1988 In

do-European Vocabulary in Old Chinese.

Jump up ^ McDonald, E. (25 March 2011). The '???' or the 'Sinophone'? Towards a

political economy of Chinese language teaching. China Heritage Quarterly, Austra

lian National University: "The term 'sinophone' seems to have been coined separa

tely and simultaneously on both sides of the Pacific: by Geremie Barm in his 2005

essay 'On New Sinology';[4] and by Shu-Mei Shih in her 'Sinophone Articulations

Across the Pacific',[5] and developed at greater length in a book by the same a

uthor."

^ Jump up to: a b DeFrancis (1984) p.42 counts Chinese as having 1,277 tonal syl

lables, and about 398 to 418 if tones are disregarded; he cites Jespersen, Otto

(1928) Monosyllabism in English; London, p.15 for a count of over 8000 syllables

for English.

References[edit]

Jump up ^ Chinese language reference at Ethnologue (16th ed., 2009)

Jump up ^ china-language.gov.cn (Chinese)

Jump up ^ "Speak Mandarin Campaign". Retrieved 2011-08-09.

Jump up ^ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarstrm, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Ma

rtin, eds. (2013). "Chinese". Glottolog 2.2. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for E

volutionary Anthropology.

Jump up ^ Mair (1991).

Jump up ^ Analysis of the concept "wave" in Proto-Sino-Tibetan.

Jump up ^ Sohn & Lee (2003), p. 23.

Jump up ^ Miller (1967), pp. 2930.

Jump up ^ Kornicki (2011), pp. 7577.

Jump up ^ Kornicki (2011), p. 67.

Jump up ^ Miyake (2004), pp. 9899.

Jump up ^ Shibatani (1990), pp. 120121.

Jump up ^ Sohn (2001), p. 89.

Jump up ^ Shibatani (1990), p. 146.

Jump up ^ Wilkinson (2000), p. 43.

Jump up ^ Shibatani (1990), p. 143.

Jump up ^ Norman (2003), p. 72.

Jump up ^ Norman (1988), pp. 189190.

Jump up ^ Ramsey (1987), p. 23.

Jump up ^ Norman (1988), p. 188.

Jump up ^ Norman (1988), p. 181.

Jump up ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 5355.

^ Jump up to: a b Wurm et al. (1987).

Jump up ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 5556.

Jump up ^ Lewis, Simons & Fennig (2013).

Jump up ^ Kurpaska (2010), pp. 7273.

^ Jump up to: a b DeFrancis (1984), pp. 5557.

Jump up ^ ARE THERE SIX OR NINE TONES IN CANTONESE? - Patrick Chun Kau Chu and M

arcus Taft, School of Psychology, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Austral

ia 2011

Jump up ^ Terrell, Peter, ed. (2005). Langenscheidt Pocket Chinese Dictionary. B

erlin and Munich: Langenscheidt KG. ISBN 1-58573-057-2.

Jump up ^ Dr. Timothy Uy and Jim Hsia, Editors, Webster's Digital Chinese Dictio

nary Advanced Reference Edition, July 2009

Jump up ^ Kane (2006), p. 161.

Jump up ^ "How hard is it to learn Chinese?". BBC News. January 17, 2006. Retrie

ved April 28, 2010.

Jump up ^ (Chinese) "????????:2005?????????12?",Gov.cn Xinhua News Agency, Janua

ry 16, 2006.

Literature

DeFrancis, John (1984), The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy, University of Ha

waii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-1068-9.

Kane, Daniel (2006), The Chinese Language: Its History and Current Usage, Tuttle

Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8048-3853-5.

Kornicki, P.F. (2011), "A transnational approach to East Asian book history", in

Chakravorty, Swapan; Gupta, Abhijit, New Word Order: Transnational Themes in Bo

ok History, Worldview Publications, pp. 6579, ISBN 978-81-920651-1-3.

Kurpaska, Maria (2010), Chinese Language(s): A Look Through the Prism of "The Gr

eat Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects", Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-021

914-2.

Lewis, M. Paul; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2013), Ethnologue: La

nguages of the World (Seventeenth ed.), Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

Miller, Roy Andrew (1967), The Japanese Language, University of Chicago Press, I

SBN 978-0-226-52717-8.

Mair, Victor H. (1991), "What Is a Chinese "Dialect/Topolect"? Reflections on So

me Key Sino-English Linguistic terms", Sino-Platonic Papers 29: 131.

Miyake, Marc Hideo (2004), Old Japanese: A Phonetic Reconstruction, RoutledgeCur

zon, ISBN 978-0-415-30575-4.

Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0

-521-29653-3.

(2003), "The Chinese dialects: phonology", in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J.

(eds.), The Sino-Tibetan languages, Routledge, pp. 7283, ISBN 978-0-7007-1129-1.

Ramsey, S. Robert (1987), The Languages of China, Princeton University Press, IS

BN 978-0-691-01468-5.

Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990), The Languages of Japan, Cambridge University Press,

ISBN 978-0-521-36918-3.

Sohn, Ho-Min (2001), The Korean Language, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0

-521-36943-5.

Sohn, Ho-Min; Lee, Peter H. (2003), "Language, forms, prosody, and themes", in L

ee, Peter H., A History of Korean Literature, Cambridge University Press, pp. 155

1, ISBN 978-0-521-82858-1.

Wilkinson, Endymion (2000), Chinese history: a manual (2nd ed.), Harvard Univ As

ia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4.

Wurm, Stephen Adolphe; Li, Rong; Baumann, Theo; Lee, Mei W. (1987), Language Atl

as of China, Longman, ISBN 978-962-359-085-3.

Further reading[edit]

Hannas, William C. (1997), Asia's Orthographic Dilemma, University of Hawaii Pre

ss, ISBN 978-0-8248-1892-0.

Qiu, Xigui (2000), Chinese Writing, trans. Gilbert Louis Mattos and Jerry Norman

, Society for the Study of Early China and Institute of East Asian Studies, Univ

ersity of California, Berkeley, ISBN 978-1-55729-071-7.

Ramsey, S. Robert (1987), The Languages of China, Princeton University Press, IS

BN 978-0-691-01468-5.

Schuessler, Axel (2007), ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese, Honolulu: U

niversity of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2975-9.

R. L. G. "Language borrowing Why so little Chinese in English?" The Economist. J

une 6, 2013.

External links[edit]

Chinese edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Classical Chinese texts Chinese Text Project

USA Foreign Service Institute Chinese basic course

Mandarin Chinese children's story in simplified Chinese showing the stroke order

for every character. on YouTube

[show] v t e

Chinese language(s)

[show] v t e

Chinese language loan vocabularies

[show] v t e

Languages of Asia

Categories: Languages with ISO 639-2 codeLanguages with ISO 639-1 codeChinese la

nguageIsolating languagesSinologyLanguage versus dialect

Navigation menu

Create accountLog inArticleTalkReadEditView history

Main page

Contents

Featured content

Current events

Random article

Donate to Wikipedia

Wikimedia Shop

Interaction

Help

About Wikipedia

Community portal

Recent changes

Contact page

Tools

Print/export

Languages

Ach

????????

Afrikaans

Alemannisch

????

???????

Aragons

?????

Avae'?

Az?rbaycanca

?????

Bn-lm-g

?????????

??????????

?????????? (???????????)?

Bikol Central

?????????

Boarisch

???????

Bosanski

Brezhoneg

??????

Catal

???????

Cebuano

Cetina

Cymraeg

Dansk

Deutsch

??????????

Dolnoserbski

Eesti

????????

Espaol

Esperanto

Estremeu

Euskara

?????

Fiji Hindi

Froyskt

Franais

Frysk

Gaeilge

Gaelg

Gidhlig

Galego

??

???????

????????????

???/Hak-k-ng

??????

???

Hawai`i

???????

??????

Hornjoserbsce

Hrvatski

Ido

Ilokano

Bahasa Indonesia

IsiZulu

slenska

Italiano

?????

Basa Jawa

Kalaallisut

?????

???????

???????

Kernowek

Kiswahili

????

Kongo

????????

?????

???

Latina

Latvieu

Lietuviu

Ligure

Limburgs

Lojban

Magyar

??????????

Malagasy

??????

?????

????

Bahasa Melayu

Mirands

??????

??????????

Nahuatl

Dorerin Naoero

Nederlands

??????

???

???????

Norsk bokml

Norsk nynorsk

Novial

Occitan

O?zbekcha

??????

??????

?????????

Picard

Plattdtsch

Polski

Portugus

Qirimtatarca

Reo Ma`ohi

Romna

Runa Simi

??????????

???????

???? ????

Smegiella

?????????

Scots

Seeltersk

Sesotho

Shqip

Sicilianu

Simple English

Slovencina

Slovencina

?????????? / ??????????

Slunski

?????

?????? / srpski

Srpskohrvatski / ??????????????

Suomi

Svenska

Tagalog

?????

???????/tatara

??????

???

??????

Trke

Trkmene

Twi

??????????

????

???????? / Uyghurche

Vahcuengh

Ti?ng Vi?t

Vro

Walon

??

Winaray

??

??????

Yorb

??

emaiteka

??

Edit links

This page was last modified on 10 May 2014 at 13:14.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; add

itional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and P

rivacy Policy. Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, I

nc., a non-profit organization.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Integrated Chinese Vol 4 TextbookDocument444 paginiIntegrated Chinese Vol 4 Textbookcuriousbox90% (10)

- Sue-Mei Wu - Chinese Link - Simplified Character Version. Level 1, Part 1 (2010, Pearson - Prentice Hall)Document313 paginiSue-Mei Wu - Chinese Link - Simplified Character Version. Level 1, Part 1 (2010, Pearson - Prentice Hall)Life Hack90% (10)

- ASSIGNMENT - Phonology of CantoneseDocument6 paginiASSIGNMENT - Phonology of CantoneseGerald Ordinado PanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- CompendiumDocument3 paginiCompendiumKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learn Mandarin Chinese For Beginners A Step Step-By - Step Guide To Master The Chinese Language Quickly and Easily While Having... (Leo W Chang (Chang, Leo W) )Document91 paginiLearn Mandarin Chinese For Beginners A Step Step-By - Step Guide To Master The Chinese Language Quickly and Easily While Having... (Leo W Chang (Chang, Leo W) )FloriiDudley0% (2)

- Foreign Language MandarinDocument12 paginiForeign Language MandarinFar MieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foreign Language MandarinDocument12 paginiForeign Language MandarinFar Mie100% (1)

- Mandarin Chinese: The Most Widely Spoken Language in ChinaDocument2 paginiMandarin Chinese: The Most Widely Spoken Language in ChinaMichelle RiñonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chinese Language (Extract From Wikipedia)Document1 paginăChinese Language (Extract From Wikipedia)sr123123123Încă nu există evaluări

- CineDocument9 paginiCineElenaDiSavoiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ChineseDocument24 paginiChineseGabriel Godoy Adel100% (1)

- Varieties of ChineseDocument31 paginiVarieties of ChineseM HAFIDZ RAMADHAN RAMADHANÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Revered General of China Year 1621Document1 paginăThe Revered General of China Year 1621jaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- ChineseDocument1 paginăChineseniÎncă nu există evaluări

- ChineseDocument1 paginăChineseDenisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chinese language: á 麻), "horse" (mă 马) orDocument2 paginiChinese language: á 麻), "horse" (mă 马) oranonymous girlÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exploring the Varieties of Chinese LanguagesDocument2 paginiExploring the Varieties of Chinese LanguagesArlene Magalang NatividadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mandarin ChineseDocument10 paginiMandarin ChineseM HAFIDZ RAMADHAN RAMADHANÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To ChineseDocument8 paginiIntroduction To Chinesemooody.hi6Încă nu există evaluări

- Mandarin ChineseDocument12 paginiMandarin ChineseAndrei ZvoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Chinese LanguagesDocument42 paginiIntroduction To Chinese LanguagesSim Tze Wei100% (1)

- DazopoDocument2 paginiDazopogilbertdanso88Încă nu există evaluări

- A Reworking of Chinese Language ClassificationDocument211 paginiA Reworking of Chinese Language ClassificationRobert A. LindsayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Taiwanese Hokkien: The Language of TaiwanDocument26 paginiTaiwanese Hokkien: The Language of TaiwankgaviolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chinese LanguageDocument24 paginiChinese LanguageSashimiTourloublancÎncă nu există evaluări

- JinDocument1 paginăJinMichelle RiñonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chinese Aslingua FrancaiDocument29 paginiChinese Aslingua FrancaiClaudia BogdanescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- EL113 CHINESE LIT. GuideDocument11 paginiEL113 CHINESE LIT. GuideMariel AttosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jin ChineseDocument2 paginiJin ChineseM HAFIDZ RAMADHAN RAMADHANÎncă nu există evaluări

- ChineseDocument19 paginiChineseNhuQuynhDo100% (1)

- SinDocument64 paginiSinyumingruiÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Introduction To Chinese Language 10 2011Document18 paginiAn Introduction To Chinese Language 10 2011reemas_94Încă nu există evaluări

- Chinese Assignmen-1Document3 paginiChinese Assignmen-1Barhee MunirÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Far Southern Sinitic Languages As Part of Mainland Southeast AsiaDocument62 paginiThe Far Southern Sinitic Languages As Part of Mainland Southeast Asiaandres0126Încă nu există evaluări

- Qieyun Yunjing: Middle Chinese Northern and Southern Dynasties Sui Tang Song Rime Book Rhyme TablesDocument1 paginăQieyun Yunjing: Middle Chinese Northern and Southern Dynasties Sui Tang Song Rime Book Rhyme TablesrosarosieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hist 220 - East Asian CivilizationsDocument52 paginiHist 220 - East Asian CivilizationsAbdulrahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Study of Chinese LanguageDocument4 paginiStudy of Chinese LanguageEzekiel FrondozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mandarin Chinese: - Dər-In Simplified GuānhuàDocument22 paginiMandarin Chinese: - Dər-In Simplified Guānhuàmamoca8588Încă nu există evaluări

- Periplus Pocket Mandarin Chinese Dictionary: Chinese-English English-Chinese (Fully Romanized)De la EverandPeriplus Pocket Mandarin Chinese Dictionary: Chinese-English English-Chinese (Fully Romanized)Încă nu există evaluări

- Asian LanguagesDocument2 paginiAsian LanguagesI114100% (1)

- Cantonese-English Dictionary: Marco BosioDocument15 paginiCantonese-English Dictionary: Marco BosioJospel GadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wu ChineseDocument24 paginiWu ChinesePlataforma ESGÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cantonese Grammar SynopsisDocument53 paginiCantonese Grammar SynopsisAndrewMTOÎncă nu există evaluări

- 0.classical ChineseDocument45 pagini0.classical ChineseAtanu DattaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sino-Tibetan Languages 漢藏語系: Tedo MenabdeDocument10 paginiSino-Tibetan Languages 漢藏語系: Tedo MenabdetedoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eastern Han Chinese languageDocument10 paginiEastern Han Chinese languageolympiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mandarin LanguageDocument6 paginiThe Mandarin LanguageRicalyn FloresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hangul HistoryDocument6 paginiHangul HistoryCarla Flor Losiñada100% (1)

- Pinyin - WikipediaDocument21 paginiPinyin - WikipediaDanielÎncă nu există evaluări

- MidchinnnnDocument8 paginiMidchinnnnInvisible CionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pinyin: 1 History of Romanization of Chi-Nese Characters Before 1949Document16 paginiPinyin: 1 History of Romanization of Chi-Nese Characters Before 1949Carlos EdreiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chinese LanguageDocument4 paginiChinese LanguagerosarosieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language Planning in ChinaDocument5 paginiLanguage Planning in Chinasailesh nimmagaddaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PlolpkjhDocument6 paginiPlolpkjhrafidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparing The Tone System in Chinese and Other Asian Languages - EditedDocument12 paginiComparing The Tone System in Chinese and Other Asian Languages - Editedsam otienoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book_1_3Document18 paginiBook_1_3reinardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chinese CharactersDocument30 paginiChinese CharactersjzainounÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mini Mandarin Chinese Dictionary: Chinese-English English-ChineseDe la EverandMini Mandarin Chinese Dictionary: Chinese-English English-ChineseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mandarin (: More Native SpeakersDocument1 paginăMandarin (: More Native SpeakersNicholas PeckÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contact and Change in The History of The Chinese LanguageDocument17 paginiContact and Change in The History of The Chinese LanguageHunĉi CanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brief History and Culture of ChinaDocument9 paginiBrief History and Culture of ChinaExodus GreyratÎncă nu există evaluări

- Studen Notebook Intro Fl1Document9 paginiStuden Notebook Intro Fl1Ethel Joy Tolentino GamboaÎncă nu există evaluări

- D. Holm - A Layer of Old Chinese Readings in Traditional Zhuang ManuscriptsDocument45 paginiD. Holm - A Layer of Old Chinese Readings in Traditional Zhuang ManuscriptsQuang Nguyen100% (1)

- Survival Korean: How to Communicate without Fuss or Fear Instantly! (A Korean Language Phrasebook)De la EverandSurvival Korean: How to Communicate without Fuss or Fear Instantly! (A Korean Language Phrasebook)Evaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Further ReadingDocument11 paginiFurther ReadingKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Loading Data With AJAX: Ajax - HTMLDocument3 paginiLoading Data With AJAX: Ajax - HTMLKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- SewingDocument7 paginiSewingKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- HedonistDocument8 paginiHedonistKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7 MySQLLDocument24 pagini7 MySQLLKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- IconoclastDocument18 paginiIconoclastKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- GleanDocument4 paginiGleanKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yellow 1 Get Your Tools ReadyDocument17 paginiYellow 1 Get Your Tools ReadyKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- GullDocument10 paginiGullKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Context Clues Lesson Plan GuideDocument4 paginiContext Clues Lesson Plan GuideKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- SewingDocument7 paginiSewingKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- OgerDocument4 paginiOgerKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- IconoclastDocument18 paginiIconoclastKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- NotoriousDocument6 paginiNotoriousKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 1Document0 paginiLesson 1Uday DuttÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lathe MachDocument10 paginiLathe MachKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- ChimneyDocument9 paginiChimneyKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lathe MachineDocument12 paginiLathe MachineKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- GiovanniDocument14 paginiGiovanniKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Text DocumentDocument3 paginiNew Text DocumentKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- AaaDocument8 paginiAaaKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- MonasteryDocument10 paginiMonasteryKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- MoonDocument10 paginiMoonKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- RomanDocument6 paginiRomanKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electr IDocument16 paginiElectr IKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- LeveretDocument3 paginiLeveretKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- VietDocument9 paginiVietKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- JapaneseDocument25 paginiJapaneseKhuong LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- LM380A Instruction Manual in Eng PDFDocument64 paginiLM380A Instruction Manual in Eng PDFJuli RokhmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chinese Hanzi WorksheetDocument94 paginiChinese Hanzi WorksheetSharon Nicole100% (1)

- Why Chinese Is So Damn Hard - Moser (1991)Document12 paginiWhy Chinese Is So Damn Hard - Moser (1991)chevro1etÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Chinese Radicals - HSK AcademyDocument11 paginiThe Chinese Radicals - HSK AcademyMassimo TormenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lonely Planet China PhrasebookDocument387 paginiLonely Planet China PhrasebookMiguel Andrew Bushmere0% (1)

- Chinese Characters - Basic PDFDocument92 paginiChinese Characters - Basic PDFttsaqa868194% (17)

- Learn Mandarin Chinese at Home with Ultimate CD CourseDocument21 paginiLearn Mandarin Chinese at Home with Ultimate CD CoursejmlorenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Level 3 Lesson 2 SimplifiedDocument9 paginiLevel 3 Lesson 2 SimplifiedNyein HtutÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pinyin+character Stroke OrderDocument4 paginiPinyin+character Stroke OrderAlexandra SmlÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson NotesDocument103 paginiLesson NotesDonny Jinjae Kim-adamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Spread of Chinese As A Global LanguageDocument13 paginiThe Spread of Chinese As A Global LanguageOanh LamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dizigui Web SimpDocument40 paginiDizigui Web SimpBhuwan K.C.Încă nu există evaluări

- Singapore Mahjong - Rules.enDocument25 paginiSingapore Mahjong - Rules.enSua jia ren AddisonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epson Service Manual TM-U220 Impact Printer Service Manual RevBDocument104 paginiEpson Service Manual TM-U220 Impact Printer Service Manual RevBeburksÎncă nu există evaluări

- 02 Introduction Page1 10Document10 pagini02 Introduction Page1 10Pascal DupontÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Write in Chinese Olly Richards and Kyle BalmerDocument24 paginiHow To Write in Chinese Olly Richards and Kyle Balmerawaismqsd100% (1)

- Guide To Reading Chinese Characters (Symbols) On Charms: Chinese Charm Inscriptions (Partial List)Document1 paginăGuide To Reading Chinese Characters (Symbols) On Charms: Chinese Charm Inscriptions (Partial List)WertholdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guide To Chinese CharactersDocument78 paginiGuide To Chinese Charactersgrigorije100% (1)

- Beginners Chinese PrintableDocument22 paginiBeginners Chinese PrintableJéssica Caetano100% (1)

- 1st LessonDocument19 pagini1st LessonSaqib SaeedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Can You Read Classical Chinese - Do You Know All 50,000 Characters - QuoraDocument30 paginiCan You Read Classical Chinese - Do You Know All 50,000 Characters - QuoraAtanu DattaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Politics of Design - Ruben PaterDocument99 paginiThe Politics of Design - Ruben PaterGabrielismÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chinese Hanzi Worksheet1.1 PDFDocument93 paginiChinese Hanzi Worksheet1.1 PDFKC100% (2)

- 03 幼童華語讀本3 (英文版) PDFDocument48 pagini03 幼童華語讀本3 (英文版) PDFDonna Chiang TouatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mandarin Lesson 2 - Chinese CharactersDocument16 paginiMandarin Lesson 2 - Chinese CharactersViaÎncă nu există evaluări