Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Research of Public Sector

Încărcat de

Haris Ali Khan0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

56 vizualizări26 paginiresearch of public sector

Titlu original

research of public sector

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentresearch of public sector

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

56 vizualizări26 paginiResearch of Public Sector

Încărcat de

Haris Ali Khanresearch of public sector

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 26

Procurement reform in the

Philippines: the impact of elite

capture and informal bureaucracy

David Seth Jones

Faculty of Business, Economics and Policy Studies, University of Brunei,

Gadong, Brunei

Abstract

Purpose The purpose of the paper is to examine features and impact of recent reforms introduced

by the Philippines government to deal with the longstanding shortcomings in its procurement system.

Design/methodology/approach The research for the paper is based on reports by international

organizations, ofcial documents of the Philippines government, surveys by international and

domestic organizations, interviews with relevant ofcials and media reports.

Findings The ndings show that the reforms have focused on fostering competition, increasing

transparency, standardizing procedures, enhancing end-product quality and contractor reliability,

ensuring proper planning and budgeting, combatting corruption, and strengthening accountability.

These reforms were intended to create a procurement system more in line with international best

practices. However the paper shows that the impact has been less than promised. This is due to

limitations of certain provisions of the reforms and weaknesses in both implementation and in the

accountability of the procuring entities. A key factor in undermining the reforms is widespread

corruption, which continues to affect many aspects of the procurement system. The article identies

two important and related reasons for such failings: elite capture of the government and bureaucracy

by a powerful network of business leaders from well-established landed families, who have close links

with the political establishment; and second, a long-established culture of informal inuence in the

Philippine state bureaucracy (what may be termed the informal bureaucracy), which has been used to

maximum effect by the elite network of business leaders. As a result, this network has been able to

inuence the reforms to serve its own interests and ensure its continued dominance of the procurement

market.

Originality/value The value of the paper is to show how administrative reforms, no matter how

well formulated they are, may be readily undermined in the process of implementation by elite groups

able to inuence government bureaucracy through an informal culture.

Keywords Philippines, Government policy, Public procurement, Corruption, Public administration,

Reform, Elite capture, Informal bureaucracy, Implementation, Public sector reform

Paper type Research paper

Introduction

One year after the overthrow of President Marcos in 1986, a new constitution in the

Philippines was adopted. After nearly 15 years of autocratic rule, this laid the

foundation for a new democratic political order. Under the more open and

representative system of government, attention was focused on the low standards of

governance that had hitherto characterised policy making and public administration in

the Philippines. The features were waste, inefciency, and lack of transparency,

widespread corruption, low levels of capacity, and the absence of accountability. Public

procurement was as much affected as other sectors of public administration, resulting

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0951-3558.htm

Procurement

reform in the

Philippines

375

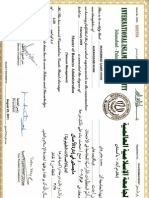

International Journal of Public Sector

Management

Vol. 26 No. 5, 2013

pp. 375-400

qEmerald Group Publishing Limited

0951-3558

DOI 10.1108/IJPSM-05-2013-0068

in poorly resourced public services and an under-developed infrastructure (World

Bank, 2008, p. 8).

A wide range of measures have been implemented to remedy these shortcomings.

Among them have been reforms to improve the system of public procurement, the

centrepiece of which have been the Government Procurement Reform Act of 2003

(GPRA) and its Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRRs) of 2005, revised in 2009.

The intention was to create a system of procurement in line with international

standards (World Bank, 2008, pp. 8-9). Priority was given to fostering competition,

increasing transparency, standardizing procedures, combatting corruption, and

strengthening accountability. Equally important objectives were enhancing

end-product quality and contractor reliability, and ensuring proper planning and

budgeting in the procurement process. While the reforms on paper have created a

procurement system more in line with international best practices, they have been

undone by limitations of certain of their provisions serious failings in their

implementation, and a lack of proper accountability. At the heart of weak

implementation and limited accountability has been continuing widespread

corruption in day-to-day procurement practices, and shortcomings of both watchdog

and enforcement bodies and also bid challenge mechanisms.

The article will rst elaborate an analytical framework, and then describe the

system of government and administration in the Philippines. After this, it will examine

the organisation, process and methods of public procurement in the Philippines as

stipulated in the procurement laws and regulations and in the procurement manuals.

The article will then consider the reforms to improve the system of procurement,

focusing on the GPRA and its IRRs, as well as other measures to combat procurement

corruption. This is followed by an examination of how the impact of the reforms has

been undermined by limitations of certain of their provisions, weaknesses in

implementation (including pervasive corruption), and failings in the system of

procurement accountability. In conclusion, the paper will explain the limited impact of

the reforms in terms of two key ideas highlighted in the analytical framework: a) the

control exercised over procurement policy and its implementation by a powerful

network of business leaders and inuential families closely connected to the political

establishment (what may be termed as elite capture); b) a long established culture of

informal inuence in the Philippine state bureaucracy which has been used to

maximum effect by elite groups.

The article will draw on a range of sources. These include the reports and data of

the Philippine government agencies, those of various international organisations,

ndings of survey organisations, relevant statutes and regulations, the procurement

manuals and the bidding documents of the Government Procurement Policy Board of

the Philippines and interviews with Philippine public procurement ofcials, as well as

academic studies of corruption in the Philippines.

Analytical framework

The analysis in the latter part of the article which focuses on the limited impact of the

procurement reforms in the Philippines is shaped by the concept of elite capture and

the related concept of informal inuence in the bureaucracy or the informal

bureaucracy.

IJPSM

26,5

376

The concept of elite capture has been long explored in the literature of sociology and

political science, two notable examples being the seminal studies of Bottomore (1993)

and Wright Mills (1956). It essentially refers to the way elite groups dominate political

life, shape policy agendas even in democratic societies, and inuence day to day

administration. Such groups may include members of powerful business networks,

prominent gures in the legal profession, top managers of state institutions, senior

ofcers in the military establishment, and in traditional societies, large landowning

families. Their inuence stems from being members of or having close links with the

political class of government ministers, elected politicians, party bosses, provincial and

local government leaders and senior bureaucrats (those links being often based on

personal, family and business connections).

Derived from the concept of elite capture is the notion of state capture which has

been expounded by the World Bank. This refers to the efforts of rms to shape the

laws, policies, and regulations of the state to their own advantage by providing illicit

private gains to public ofcials (Hellman et al., 2001). In other words, state capture is a

form of elite capture by businesses to inuence the formation of policy and the drafting

of laws and regulations (Hellman et al., 2000).

Elite capture can go further and entail day to day decisions in policy

implementation. An example is regulatory capture, in which businesses and

nancial institutions affect how regulations are applied to ensure their interests are

safeguarded (Adams et al., 2007). The inuence over policy implementation may be

exercised through direct interference or indirectly through powerful intermediaries in

the political establishment.

Also affected by elite capture are watchdog and enforcement bodies with responsibility

to ensure government agencies are accountable for their performance. Such bodies may

likewise be subject to interference by elite groups in their efforts to expose and deal with

shortcomings in government agencies As Klitgaard (1998) has pointed out, this weakens in

particular efforts to combat corruption, which is further compounded by the absence of a

determination of political leaders to support those efforts (pp. 500-5).

The other concept shaping the discussion is the informal bureaucracy. Two aspects

of the informal bureaucracy are relevant to this study. One is the extent to which

ofcials in public agencies respond to ambiguities in rules and regulations by

developing their own criteria in making decisions and their own unwritten practices.

The other is the willingness of ofcials, especially in the bureaucracies of developing

countries, to make decisions and follow procedures deviating from policy statements,

laws and regulations, and to develop informal networks with elite groups. Such groups

may thereby exercise inuence over policy making and implementation (Woods and

Shlapentokh, 2009, pp. 538-45).

There is of course a connection between elite capture, the use of the informal

bureaucracy, and corruption. Michael Johnston has examined this connection,

identifying various types of elite control. One type of elite control he identies is the

oligarch and clan control, in which business elites and top ofcials, with powerful

personal and family connections, take advantage of a setting of rapidly expanding

political and economic opportunities and weak institutions to engage in corruption.

This type of elite control exploiting informal bureaucracy and weak institutions, is

reected, according to Johnston, in the Philippines ( Johnston, 2005, pp. 3, 44-6, 8, 120-4,

136-44; Johnston, 2010, pp. 7-13, 40-1).

Procurement

reform in the

Philippines

377

Elite capture through the informal bureaucracy is further guaranteed by the low

status of ofcials with management and operational responsibilities. Such ofcials nd

it difcult to resist the direct or indirect interference of members of powerful elite

groups, partly out of natural deference, especially in a traditionally ascriptive culture.

Equally important is the concern that resisting elite demands will harm their career

prospects, while acceptance will enhance them. This is coupled with the knowledge

that acceptance will also result in personal gain through bribery and kickbacks. In

consequence, ofcials have a commitment to and a stake in preserving the status quo.

This, Kelman has observed in his study of procurement reform, leads front-line

ofcials to erect a wall of resistance so as to ensure such reform does not lead to

genuine change. In his view, only when dissatisfaction with the status quo grows

among front-line ofcials do the prospects for genuine change in government agencies

increase (Kelman, 2005, pp. 5-9, 20-5, 39-54).

The problems encountered in the reforms of the procurement system in the

Philippines will be considered as reecting elite capture based on oligarchic and clan

control by powerful business groups and inuential landowning families, whose

inuence is facilitated by the prevalence of the informal bureaucracy.

System of government and administration in the Philippines

The 1987 Constitution established a democratic form of government in the Philippines

based on the presidential-congressional model in the US. It functions on the basis of

checks and balances between three co-equal and separate branches of government: the

executive, legislature and judiciary. At the head of the executive is the President, who is

also Head of State, supported by the vice-president, and a cabinet appointed by the

President comprising mainly political heads of the executive departments, known as

secretaries. The President and vice-president are each elected in separate elections, which

are themselves separate from elections to the legislature. Each incumbent serves a single

xed term of six years. The legislature comprises the bi-cameral Congress, consisting of

a 24 seat Senate (upper house) and a House of Representatives (lower house), with 240

seats. Senators serve six year terms while representatives three year terms.

There are four main types of institution in the state bureaucracy of the Philippines.

At the core are 17 executive departments directly under the control of the executive,

and various constitutional and specialist commissions (both commonly referred to as

national government agencies). In addition, currently 78 government-owned or

controlled corporations exist, many of which provide basic services and engage in

business-related activities. Some of them are stock corporations in which the

government through its holding companies owns all or the majority of the shares.

Others are non-stock corporations. All are governed by a board of directors, and

though raising their own revenue, most continue to rely on government subsidies. At

the local level, public services are delivered and certain types of infrastructure project

undertaken by local government units. These are organised into three tiers: provinces

(plus the autonomous region of Mindanao) at the highest level, which are divided into

cities and municipalities, each of which is sub-divided into barangays (local councils).

Under the civil service decree, all of these organisations are counted as part of the civil

service, including somewhat surprisingly government-owned or controlled

corporations and local government units (De Leon, 2002; Brillantes, 2009,

pp. 186-206; Government of the Philippines, 2010).

IJPSM

26,5

378

The size of the state bureaucracy is not excessive by international comparison. The

payroll at the end of 2010 totalled 2,948,000 ( just 9.2 per cent of the working

population) including those working in government-owned or controlled corporations,

local government units, the police force and teaching service. Of this number, 1,771,000

are engaged in public administration, defense and social security (Bureau of Labor

and Employment Statistics, 2011). Total government expenditure was a modest 18.4

per cent of GDP at the outturn of 2009, increasing from just over 17 per cent in the

previous four years (ADB, 2010, p. 262). Only three of the nine countries of Southeast

Asia have a lower aggregate of public expenditure relative to GDP. The decit of 5.3

per cent of GDP recorded in 2002 had been gradually brought down, reaching 0.9 per

cent in 2008, before increasing to 3.9 per cent at the outturn of 2009 (ADB, 2010, p. 259).

Despite the recent record of scal restraint and sound nance, subsidies to

government-owned or controlled corporations, and general waste and inefciency

continue to be a drain on the public purse.

The system of procurement

Organization of procurement

The system of public procurement in the Philippines is based on a conventional two

tier structure. At one level, operational responsibility for procurements is delegated to

the line agencies (national government agencies, government-owned or controlled

corporations and local government units), which in performing this role, are known as

procuring entities. In each procuring entity, practical management of the procurement

is undertaken and the recommendation of the contract award is made by the bids and

awards committee (BAC) (Government of the Philippines, 2009; Government

Procurement Policy Board, 2009a, pp. 12-13; Government Procurement Policy Board,

2009b, pp. 14-127). The BAC is supported by a technical working group, consisting of

suitably qualied personnel with technical, nancial and legal expertise in the area

relevant to procurement. Its role is to help the BAC in those aspects of procurement

which require such expertise, including drafting specications, evaluating bids and

drawing up contracts (Government of the Philippines, 2009; Government Procurement

Policy Board, 2009a, pp. 18-19).

Over and above the procuring entities is an umbrella body, the Government

Procurement Policy Board. It is responsible for the formulation of procurement policy,

and recommending amendments of the GPRA, as well as drafting and amending the

IRRs. Also part of its brief is to draft and amend the procurement manuals and

bidding documents. While not involved in day-to-day purchasing, the Board exercises

supervision over procuring entities to ensure they comply with the GPRA and its

IRRs, and other laws relating to procurement. Another part of its remit is to build up

expertise in procurement by organising and conducting training courses through its

technical support ofce, that cover the legal, nancial and technical aspects of the

procurement process (Congress of the Philippines, 2003; Government of the

Philippines, 2009).

The importance of the Government Procurement Policy Board is reected in the fact

that its membership largely consists of the secretaries of key executive departments. It

is chaired by the secretary of the Department of Budget and Management, with the

secretary of the National Economic and Development Authority designated as

vice-chairman. Other positions on the Board are occupied by secretaries from a range

Procurement

reform in the

Philippines

379

of departments, as well as a representative from the private sector appointed by the

President on the recommendation of the Board. Representatives from the Commission

on Audit, other public bodies and private companies may be invited to serve as

resource persons (Government of the Philippines, 2009).

Methods and processes of procurement

All the normal methods of procurement of goods, consultancy services and public

works (infrastructure projects) may be used by procuring entities in the Philippines.

Under the GPRA and its IRRs, the main method for higher value bids is the open

tender, in which all interested and eligible suppliers and contractors may participate.

At the outset, the specications detailing the features of the goods, services and works

to be acquired are drafted by the BAC of the procuring entity together with a

conrmation of the approved budget for the contract. The tender is then advertised,

and companies may respond by forwarding to the procuring entity an expression of

interest.

In the procurement of goods, companies who have expressed an interest are invited

to submit together both an application for eligibility to bid and their bid proposal. In

conjunction with this, one or more pre-bid conferences attended by would-be bidders,

may be conducted in order to clarify important details, as discussed in the following.

The bids submitted must consist of three envelopes to be handed in at the same time:

one containing the application for eligibility to bid, a second containing the technical

proposal of the bid and the third the nancial proposal (price offer). The eligibility

screening focuses on, among other things, the track record of the company, its nancial

standing, any commitment it may have to on-going contracts, and its fulllment of

nationality requirements. If any company fails to meet eligibility requirements, its bid

proposals cannot then be considered and its bid is rescinded. In the case of tenders for

infrastructure projects and consultancy services, companies who have expressed an

interest apply for eligibility to bid prior to the pre-bid conference and before they

submit their bid proposals. Those companies declared eligible are then required to

submit only two envelopes: one containing the technical and the other the nancial

proposal (Government of the Philippines, 2009; Government Procurement Policy

Board, 2009a, pp. 45-7).

After this, the evaluation of the bid proposals is undertaken by the BAC. The rst

step is to conduct a preliminary evaluation of the proposals to check if all necessary

documents and information have been submitted. A bidder will be disqualied if any

of the required documents is missing or does not contain the information required.

Once this is done, a detailed evaluation of both sets of proposals is carried out

(Government of the Philippines, 2009; Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009a,

pp. 45-7).

In tenders for goods and infrastructure projects, the technical proposals are rst

evaluated to determine if they meet the specications of the procurement. For those

that do (referred to as responsive bids), the corresponding nancial proposals are

considered. The bid offering the lowest price, known as the lowest calculated bid, is

provisionally selected. In tenders for consultancy services, after determining those bids

which meet the specications, the highest rated bid is identied within a ranking

based either on quality of the technical proposals only, or on both the quality of the

technical proposals and price or fee offered, as will be discussed in the following

IJPSM

26,5

380

(Government of the Philippines, 2009; Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009b,

pp. 57-8; Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009c, pp. 53-4; Government

Procurement Policy Board, 2009d, pp. 58-9).

On the completion of the evaluation, the chosen bidder is subject to a

post-qualication check to conrm the validity, authenticity and accuracy of all

documents and particulars submitted. If everything is in order, the bid is declared the

lowest calculated responsive bid, or the highest rated responsive bid (for a

consultancy contract). The bidder is then duly recommended to be awarded the

contract by the BAC (Government of the Philippines, 2009; Government Procurement

Policy Board, 2009b, pp. 57-8; Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009c, pp. 53-4;

Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009d, pp. 58-9),

In the case of technically complex procurements such as a large IT or infrastructure

project, the open tender may entail a two-stage bidding process. Specications are

initially broadly dened and a rst round of bidding is conducted. Those bids that best

meet the specications are short-listed. Following negotiations with the short-listed

bidders, the specications are revised and expanded. A second round of bidding is then

conducted based on the more detailed specications, in which the short-listed bidders

submit revised proposals. The two-stage bidding process allows bids which are

inadequate to be weeded out in the rst round and also enables the procuring entity to

redraft specications in light of the initial proposals and further information (usually

from negotiations) provided by short-listed bidders (Government of the Philippines,

2009; Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009a, p. 95).

Alternatives to open bidding may be adopted in certain situations dened in the

IRRs, and involve less or no competition. These include limited source tendering

(sometimes called selective tendering), in which only pre-selected suppliers are invited

to bid, and shopping, applicable to low value and routine purchases, in which three or

more pre-selected suppliers are invited to submit price quotations. The maximum

threshold for shopping is normally Philippine Peso (PhP) 500,000 (US$11,500), but can

be below this in smaller local government units. In addition, single source procurement

may be undertaken. The main one is negotiated procurement in which the procuring

entity, instead of adopting a tender, pre-selects one company who is awarded the

contract after negotiation. Single sourcing can also be applied to simple and low value

purchases, being referred to as direct contracting (Government of the Philippines, 2009;

Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009b, pp. 81-96; Government Procurement

Policy Board, 2009c, pp. 73-7; Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009d, pp. 81-7).

Reforms of public procurement

In response to the long standing failings in public procurement in the Philippines,

reforms have been implemented in recent years. These are contained within the GPRA,

the IRRs and procurement instruction manuals, as well as in measures to improve the

accountability of the state bureaucracy and to combat corruption. These reforms will

be discussed in the following.

Creating a more competitive system of procurement

Over the years, many of shortcomings in public procurement in the Philippines were

due to the lack of a genuinely open and competitive system of procurement. A central

aim of the GPRA and the IRRs is to establish this, so as to ensure value for money and

Procurement

reform in the

Philippines

381

fairness based on equal access. Both the GPRA and the IRRs stipulate open

competitive bidding as the standard method of public procurement, while the IRRs

state also that BACs shall evaluate all bids on an equal footing to ensure fair and

competitive bid comparison (Congress of the Philippines, 2003; Government of the

Philippines, 2009).

Further enhancing competition are the restrictions and prohibitions placed on the

various means that could be used by procuring entities to avoid competitive bidding.

Of particular importance are the restrictions imposed on less competitive methods of

procurement mentioned previously limited source tendering, shopping, direct

contracting, and negotiated procurement, as well as repeat orders, and adjacent or

contiguous projects (an additional project similar to and extending an on-going

project). The range of situations in which these are permissible is narrowly and clearly

dened, and entail circumstances in which it is obviously sensible and justied to

avoid competitive tendering. For example, the conditions in which negotiated

procurement is permitted, as stipulated in the IRRs, are two failed rounds of bidding,

emergency cases, projects requiring highly technical consultants, contiguous

contracts, purchases involving NGO and community participation, and small value

purchases. Competition is enhanced too by the strict prohibition on the splitting of

contracts under the GPRA and its IRRs. Splitting involves dividing the quantity of a

bulk item to be purchased into several smaller quantities. The value of the procurement

of each quantity is thus reduced to the extent that a less a competitive form of

procurement is permissible such as shopping or direct contracting (Government

Procurement Policy Board, 2009b, pp. 59, 65, 94).

Enhancing procurement planning and budgeting

Another reform under the GPRA was to establish a mandatory framework of

procurement planning and budgeting. Hitherto, government agencies often did not

draw up detailed yearly procurement plans, since there was no legal obligation to do

this. Those doing so, did not then always adhere to them. Without proper planning,

there was little way of determining whether the procurements were compatible with

the policy priorities of the procuring entity and how much of its capital and current

budgets to earmark for them. A consequence of the latter was that approved

procurements were not undertaken or projects were abandoned or delayed for lack of

sufcient funds (World Bank, 2003, pp. 22-8; Government of the Philippines, 2009;

Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009a, pp. 31-42).

As the rst stage in the planning process, according to the GPRA and its IRRs,

end-user units of a procuring entity draft a list of requested procurements for the

following nancial year, including a statement of the need for each procurement. They

provide details in each case of the type and extent of the goods, services and public

works to be procured, the procurement method to be adopted, time schedules of the

procurement and contract implementation, and the estimated contract value. The list,

known as the project procurement management plan, is then submitted to the budget

ofce of the procuring entity for its evaluation. If approved, it is vetted by the head of

the procuring entity, following which, subject to any amendment, it is consolidated

with the plans of the other end user units to form the annual procurement plan of the

procuring entity. Once the budget for the procuring entity has been nalized, as part of

the national budget, and approved by the Congress, the end-user units will be asked to

IJPSM

26,5

382

adjust their project procurement management plans in light of the funding allocated to

their programs and activities. The annual procurement plan of the procuring entity is

then accordingly amended and submitted to the BAC for its nal evaluation and

approval (Government of the Philippines, 2009; Government Procurement Policy

Board, 2009a, pp. 31-42).

Creating greater transparency and standardization in procurement

Down the years, public procurement in the Philippines has been characterised by a lack

of transparency. While the laws and regulations governing procurement prior to the

GPRA emphasised transparency, they were often ignored or sidestepped. Although

procurements were generally advertised and bid awards published, the procurement

process itself was characterised by behind the scenes deals to ensure that a contract

was awarded to a particular company, even in open tenders. Alternatively re-bidding

was permitted without any explicit justication, so as to allow a favoured company to

re-submit a price or proposals to ensure that it secured the contract (World Bank, 2003,

p. 22). Making matters worse was the fragmentation of the procurement system. The

World Bank noted in its assessment report of 2003 that there existed a proliferation of

outdated and fragmented laws and [a] multiplicity of uncoordinated executive

issuances. It further commented that at times they are inconsistent with one another

and constitute a source of confusion (World Bank, 2003, pp. 10-11).

The GPRA has sought to address both these issues, and included transparency and

standardisation among it guiding principles. A number of measures were stipulated to

enhance transparency. One was to allow outside observers from the Commission on

Audit and civil society to attend meetings of BACs, and be given access to all relevant

documents. This is provided for in section 13 which states:

To enhance the transparency of the process, the BAC (bids and awards committee) shall, in all

stages of the procurement process, invite, in addition to the representative of the Commission

on Audit, at least two observers to sit in its proceedings, one from a duly recognized private

group in a sector or discipline relevant to the procurement at hand, and the other from a

non-government organization: provided, however, that they do not have any direct or indirect

interest in the contract to be bid out (Congress of the Philippines, 2003).

The private group mentioned previously may include for goods, a relevant chamber of

commerce, for infrastructure projects one of the recognized associations in the

construction and engineering sector, and for consulting services a professional

association such as the Philippine Institute of Certied Public Accountants and the

Confederation of Filipino Consulting Organizations (Government of the Philippines,

2009). A key civil society organization that has been involved as an observer is

Procurement Watch Inc, whose task is to expose corruption and waste in procurement

(Kristina and Pimentel, 2005, pp. 42-4).

After the award of the contract, the observers individually or jointly are required to

submit a report to both the head of the procuring entity and to the Public Procurement

Policy Board. These contain their feedback on the meetings attended and the

documents examined, pointing out any irregularities that may have been committed. It

is reasoned that with outside observers the procurement process can be independently

assessed to determine if due procedures have been followed, the method of

procurement adopted is in accordance with the conditions laid down in the GPRA and

its IRRs, and the awards made are in favour of the lowest calculated responsive bid

Procurement

reform in the

Philippines

383

for goods and infrastructure projects or highest-rated responsive bid for consulting

services (Kristina and Pimentel, 2005, p. 43; Congress of the Philippines, 2003;

Government of the Philippines, 2009).

Also in the interests of transparency, the GPRA mandated the disclosure of the

approved budget for the contract in the tender notice, with the stipulation that any bids

above that would be discarded. This is intended as well to forestall collusion resulting

in awards at abnormally high prices. The ceiling is now specied in all tender notices,

though the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank have expressed misgivings

on the grounds that normal price competition may be distorted by such disclosure

(World Bank, 2008, pp. 10, 28, 34-5).

Another aspect of the procurement process introduced by the GPRA which has

promoted transparency are pre-bid conferences. Under this arrangement, the BAC of

the procuring entity meets the prospective bidders, before bids are submitted. The

purpose of the meeting is to explain eligibility requirements, clarify specications,

answer queries and where necessary to arrange on-site visits for infrastructure

projects. Pre-bid conferences are useful in the case of technically complex

procurements and reduces confusion and uncertainty on the part of bidders when

they submit their bid proposals. For contracts with an approved budget of PhP1

million (US$22,900) or more, at least one pre-bid conference is mandatory. Under that

amount, any pre-bid conference is at the discretion of the procuring entity (ADB and

OECD, 2006a, pp. 4, 8; Government of the Philippines, 2009).

The most signicant step to enhance transparency was the creation of a

comprehensive E procurement system, known as PhilGEPS, set up in 2007. The

expressed aim is that it becomes the primary source of information for procurement,

and creates a more efcient, convenient, transparent, and open procurement process

(Philippine Public Procurement Service, 2010). PhilGEPS publishes procurement laws,

regulations and bidding procedures, and announces procurement opportunities, known

as bid notice abstracts, with a facility for downloading bid documents. Bid notice

abstracts contain information on the type of goods, services and infrastructure project

to be procured, the approved budget ceiling for the contract, any pre-bid conference,

and the method of procurement to be adopted (shopping, open bidding etc.). The on-line

portal too discloses the name of the company awarded a contract, the reason for the

award, and the contract sum. A further provision is an E catalogue for purchasing low

value items (Philippine Public Procurement Service, 2010). However, there is no facility

yet for submitting on-line quotations and bids, although this, together with electronic

payment of suppliers and contractors, are part of the plan to expand the role of the E

procurement system over the next two years (World Bank, 2008, pp. 9-10, 16, 18-19, 40).

Also facilitating greater transparency in the Philippines has been the

standardisation of procurement procedures, through the use of procurement

manuals to be used by all agencies, model contracts, and uniform bid documents.

The bid documents sent to the would-be bidder must comprise or state the approved

budget for the contract, invitations to apply for eligibility and to bid, eligibility criteria,

detailed technical or functional specications, bid evaluation criteria, information of

post-qualication, conditions of contract, instructions for submitting a bid, and date,

time and place of both the pre-bid conference, and the submission and opening of bids.

Included too are standard bid submission forms to be completed or signed by the

bidder and returned to the procuring entity, including forms stating price offered,

IJPSM

26,5

384

detailing the technical proposal, and indicating delivery time or completion schedule

(Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009e, pp. 1-35). This contrasts with the

previously fragmented and opaque procedures, instructions, and document formats

which varied from one procuring entity to another (ADB and OECD, 2006b, pp. 4, 6-7;

World Bank, 2008, pp. 6, 10, 16, 51-55). Standardisation has been achieved in part by

aligning the procurement rules, procedures, manuals, and bidding documents with

those of the World Bank and ADB (World Bank, 2008, pp. 51-5).

Promoting quality and reliability

In response to long standing concerns about the quality of the end product and

reliability of suppliers and contractors, measures to improve both were incorporated

into the GPRA and its IRRs. Reliability refers to the likelihood of suppliers and

contractors nishing a project or completing it on schedule.

With respect to quality, the main priority has been to upgrade the standard of

consultancy services for infrastructure projects. To ensure a high caliber of technical or

design proposals, either of two methods of evaluation are used in consultancy tenders.

One is called the quality-based evaluation procedure. The consultants submit a

technical or design proposal and fee offer in separate envelopes. The technical or

design proposal of each submission is numerically rated and after a ranking is done,

the highest rated bid is identied. The fee offer of that bid is then considered, and the

rm in question is then asked to negotiate a nal fee which cannot exceed either the

approved budget for the contract or the fee offered (Government Procurement Policy

Board, 2009a, pp. 58-60). The second method of evaluation is the quality-cost

evaluation procedure. Again the consultants submit two separate envelopes for the

technical or design proposal, and the fee offer. Separate numerical ratings are given for

the technical or design proposal and the fee proposal. The fee proposal rating is

calculated based on the lowest bid scoring method, so that the maximum rating is

given to the lowest bid (100 points) with the scores of the other bids being inversely

proportional to it. The overall rating of each bid is then calculated with a weightage of

60 to 85 per cent accorded to the rating of the technical or design proposal and a

weightage of 15 to 40 per cent given to the rating of the fee proposal (Government

Procurement Policy Board, 2009d, pp. 58-61; Government of the Philippines, 2009).

The evaluation of the technical or design proposal must take into account the plan

of approach and methodology with the emphasis on the clarity, feasibility,

innovativeness and comprehensiveness together with the quality of interpretation of

project problems, risks, and suggested solutions (Government of the Philippines,

2009). Also included in the evaluation is the caliber of personnel assigned to the project

with respect to their experience, qualications, education and training, as well as the

overall experience of the rm and its quality of performance in similar previous

projects (Government of the Philippines, 2009).

To determine if a company is reliable and equal to the task of undertaking and

completing a project, certain requirements have been incorporated into the eligibility

screening. To be eligible, the company must prove it has the nancial means to

undertake the project. For this purpose, it must have completed in a recent period

(specied in the bidding documents) a similar contract worth at least half of the

approved budget for the contract under tender, or two or more similar contracts which

together are equal to this amount (of which one contract must be 50 per cent of this

Procurement

reform in the

Philippines

385

amount). In addition, the company must have a cash facility in or a credit line

certicate from an approved bank equal to 10 per cent of the approved budget for the

contract, or a net nancial contracting capacity (NFCC) at least equal to the approved

budget. The NFCC is a multiple of its current net worth discounted by the value of the

incomplete portion of its on-going projects. The multiple ranges from 10 for contracts

of less than one year to 20 for contracts extending over two years or more. To further

ensure reliability, the company must declare contracts either on-going or in the

immediate future to which it is committed. This is intended to address the concern that

suppliers and contractors often are unable to complete a project or may nish it behind

schedule as a result of such commitments (Government of the Philippines, 2009;

Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009c, pp. 31-4).

To further attain high standards in public infrastructure projects, contractors are

evaluated under the Constructors Performance Evaluation System (CPES). Ratings are

given for standards of workmanship, the quality of materials used, the progress made

if an on-going project, and the timeliness of completion. Also rated are regard for

environmental health and safety and the use of resources in site management. Two

overall ratings out of 1.0 are given, each being an aggregate of the individual weighted

ratings: one is given during the project and the other at the end. A score below .75 is

poor, and between .75 and .82 unsatisfactory. A score between .82 and .89 is

satisfactory and from .89 to .96 very satisfactory, with any score above that rated as

outstanding. The individual and aggregate ratings are taken into account in eligibility

screening and in bid evaluation in a subsequent project. As well, they facilitate quality

control during the project, and help to determine whether the certicate of completion

should be issued at the end (Construction Industry Authority of the Philippines and

Philippine Domestic Construction Board, 2009, pp. 1-5; Government Procurement

Policy Board, 2009c, pp. 82-3).

Furthermore, when goods, services and public works are sub-standard, the supplier,

consultant or contractor can be disqualied from public bidding for one year, and if

repeated in a subsequent contract, for two years. In the case of consultants, this applies

to producing defective designs and prescribing materials which are inappropriate

and sub-standard. Contractors may be blacklisted for abandonment of project, tardy

progress in its execution, and failure to meet other contractual terms relating to the

quality of materials and workmanship (Government of the Philippines, 2009;

Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009a, pp. 63-72; Government Procurement

Policy Board, 2009c, pp. 58-59).

Combatting corruption in procurement

Corruption has been widespread in public procurement. All the major types of

corruption have been pervasive including bribery, kickbacks, embezzlement, fraud,

cronyism, nepotism, and collusion. Since 1987 a number of reforms have been

instituted to combat procurement-related and other forms of corruption (Quah, 2003a,

pp. 91-4; Quah, 2003b, pp. 251-2). The foundation for these reforms was actually laid as

far back as 1960 through the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. Several key reforms

have been passed in recent years to build on this legislation. One were provisions

within the Constitution of 1987, spelling out the ethical responsibilities of public

ofcials. These were followed by an Act Establishing a Code of Conduct and Ethical

Standards for Public Ofcials and Employees, passed in 1989, which laid down in a

IJPSM

26,5

386

more detailed form the legally binding standards of personal integrity of civil servants

(Congress of the Philippines, 1989). In addition, in 1991, the Act Dening and

Penalizing the Crime of Plunder was passed, intended to deter mass embezzlement.

Referred to as ill-gotten wealth of at least 75 million pesos (US$1.72 million), such

embezzlement shall be punished by life imprisonment with perpetual disqualication

from holding any public ofce (Congress of the Philippines, 1991).

The proscriptions of corrupt practices were spelt out as well in the GPRA, its IRRs

and the procurement manuals. Among the forms of corruption highlighted are unduly

inuencing or exerting undue pressure on any member of the BAC (bids and awards

committee) or any ofcer or employee of the procuring entity to take a particular

bidder and offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting of anything of value to inuence

key decisions in the procurement process (Congress of the Philippines, 2003;

Government of the Philippines, 2009; Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009a,

p. 63; Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009e, p. 14). This is designed to combat

bribery, kickbacks and inuence pedalling, involving members of BACs, other public

ofcials (including elected politicians), and private individuals. To combat nepotism,

no head of a procuring entity can reject bids as a result of manifest preference to any

bidder who is closely related to him. A family member or a close relative is legally

dened in the Philippines as consanguinity or afnity up to the third civil degree.

Equally important are specic provisions prohibiting collusion and bid rigging by

companies, feigning of competition through multiple bids by one company and

fraudulent practices (submitting false information to gain eligibility to bid or to win a

bid) (Government of the Philippines, 2009; Government Procurement Policy Board,

2009a, pp. 63-7).

The GPRA, its IRRs and the procurement manuals specify the penalties (both

judicial and administrative) that can be levied for the main types of corruption

offenses. As a measure of the seriousness with which such offenses were viewed by the

framers of these reforms, those who have been convicted, whether public ofcials or

private individuals, are liable to prison terms ranging from six to 15 years. If a

company or partnership has committed the offense, then any directors, ofcers, or

employees directly involved are convicted. Furthermore, the partnership or company

may incur civil liabilities, requiring it to pay liquidated damages for any resultant loss

incurred by the procuring entity, and to pay compensation to its competitors in the

tender (Congress of the Philippines, 2003; Government of the Philippines, 2009).

In addition, administrative penalties are levied on offending individuals and

entities. Those who are public ofcials will be permanently or temporarily disqualied

from holding ofce in a public agency. Businesses who have engaged in unsolicited

bribery, collusion, and fraud, as well as committing other forms of default, can be

disqualied for one year from public bidding, and then two years if the offense is

repeated. When the corrupt or defaulting practice occurs during project

implementation, the contract can be immediately terminated (Congress of the

Philippines, 2003; Government of the Philippines, 2009; Government Procurement

Policy Board, 2009a, pp. 63-7).

Whats more, if the president, chairman, and any shareholder owning 20 per cent or

more of the equity of a disqualied corporation (and also their family members), hold

any of these positions in another company, that corporation will be likewise

disqualied from public bidding for the same period. One of the intentions is to prevent

Procurement

reform in the

Philippines

387

a rm debarred for corruption or other defaulting practices being re-registered under a

different name and articles of association and so able to still tender for public contracts

(Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009a, p. 70).

In addition to the direct prohibition of corrupt dealings, attention has been given to

preventing conicts of interest in the procurement process, which could result in

ofcials favouring businesses to which they or their families are connected. Under the

Constitution of the Philippines, public ofcials (both elected and non-elected) are

required on taking ofce to declare their assets, liabilities and net worth. Under the

Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards referred to previously, they are obliged to

relinquish any position, shareholding, or partnership stake in a business where a

conict of interest arises, and shall not, directly or indirectly, have nancial or

material interest in any transaction which requires the approval of their ofce

(Congress of the Philippines, 1989; Quimson, 2006, pp. 19, 29). This is reinforced under

the GPRA by the stipulation that no bidder can be related to the head of the procuring

entity, any member of the BAC, its secretariat, and the technical working group, the

head of the project management ofce, or any of the project consultants. The bidder

includes the sole proprietor of a business, or any partner, director, ofcer, or

shareholder with 20 per cent more of the ownership of a partnership or company

(Congress of the Philippines, 2003; Government of the Philippines, 2009; Government

Procurement Policy Board, 2009e, p. 15).

Creating and strengthening watchdog and enforcement institutions

A key aspect of the reform of public procurement in the Philippines has been to make

procuring entities more accountable by creating or strengthening watchdog and

judicial bodies, which monitor procurement practices and enforce the relevant laws and

regulations. There has now arisen a signicant group of institutions whose remit is to

exercise oversight over the procurement process, to unearth evidence where anomalies

have occurred, and, where appropriate, to facilitate, initiate or undertake enforcement

action. The key watchdog institutions, which have been created or whose powers have

been increased, are the Commission on Audit, the Ofce of the Ombudsman, the

Government Procurement Policy Board, Sandiganbayan (anti-graft court) with the

remit to try high level cases of corruption, and the Procurement Transparency Board.

However, the Presidential Anti-Graft Commission was abolished in November 2010,

with its functions (mainly to investigate corruption of presidential appointees)

transferred to the Ofce of the Deputy Secretary for Legal Affairs under the Ofce of

the President.

Worth noting is the revamped Ofce of the Ombudsman (OO), established under the

Ombudsman Act of 1989, which has become the lead investigative and enforcement

agency in combatting corruption and has the power not only to investigate corrupt

dealings but also to prosecute those who are charged, even supplanting the role of the

public prosecutor (Quimson, 2006, pp. 26-7; Ofce of the Ombudsman, 2009). The work

of the Ombudsman has been helped by the Procurement Transparency Board, set up in

2007. Composed of a mix of senior public ofcials and civil society representatives, its

mandate is to oversee the management of a tender. When deviations from the

provisions of the GPRA and its IRRs occur, it may recommend to the Ombudsman the

ling of penal, civil and administrative charges (Ofce of the President, 2008).

IJPSM

26,5

388

Limitations in certain provisions of the reforms

Although the GPRA and its IRRs are comprehensive, certain provisions still create

obstacles to the achievement of a procurement system in line with international best

practices. The main ones are those which impose restrictions on access to the

procurement market for overseas rms, despite the commitment to competition

mentioned previously. As stated in a resolution of the Government Procurement Policy

Board in, 2005, the GPRA adopts as a general principle preference for Filipino

nationals in the award of government contracts in line with the policy to promote

Filipino labor, domestic materials, and locally produced goods (Government

Procurement Policy Board, 2005).

As reafrmed in the 2009 revised IRRs (section 23) and procurement manuals, a

business may be eligible to bid for the supply of goods and to provide consultancy

services, if 60 per cent of the ownership is in the hands of Philippine nationals, with a

further requirement that the actual delivery of consultancy service be undertaken by a

Philippine national(s). In tenders for infrastructure projects, it is mandated that, in

most cases, 75 per cent of the ownership of the company must belong to Philippine

nationals (Government of the Philippines, 2009; Government Procurement Policy

Board, 2009b, pp. 43-5; Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009c, pp. 31-3;

Government Procurement Policy Board, 2009d, pp. 34-5; Government Procurement

Policy Board, 2009e, p. 16).

Under the IRRs, foreign companies are allowed to participate in a restricted number

of situations. Their eligibility to bid may be granted when provided for under any

Treaty or International or Executive Agreement (including donor sponsored projects),

and when the goods sought to be procured are not available from local suppliers [. . .]

or when there is a need to prevent situations that defeat competition or restrain trade.

The hiring of foreign contractors in infrastructure projects is only permitted in the rst

situation mentioned previously. Under section 43 of the revised IRRs, even when

foreign suppliers and contractors are allowed to tender, a preferential margin is applied

in favour of domestic businesses. In this case, the lowest of the domestic bidders will be

awarded the contract so long as its price is no more than 15 per cent above the lowest

price offered by the foreign bidders, and provided it is willing to match that price offer

(Government of the Philippines, 2009).

It should be noted that the restrictions on foreign participation in tenders were

included in the revisions to the original version of the Government Procurement

Reform Bill introduced during its passage in the House of Representatives (Campos

and Syquia, 2006, p. 25). It is difcult to know what pressures and considerations were

brought to bear on this matter, but it could be surmised that inuence may have been

exerted by those business groups in the Philippines who had hitherto dominated the

procurement market and thus sought to protect their own interests.

As mentioned previously, the GPRA lays down restrictive and well dened

conditions under which procuring entities may avoid competitive tendering. However,

under two of the provisions of the GPRA, limited tendering is allowed for the

procurement of highly specialized types of goods and consulting services which are

known to be obtainable only from a limited number of sources and for the purchase of

major plant components where it is deemed advantageous to limit the bidding to known

eligible bidders in order to maintain an optimum and uniform level of quality and

performance of the plant as a whole (Congress of the Philippines, 2003). Such terms as

Procurement

reform in the

Philippines

389

specialized, limited number, advantageous, optimum, and as a whole are all a

matter of interpretation, so giving procuring entities discretion in deciding whether to

adopt limited tendering. Such ambiguity may allow powerful elite groups to unduly

inuence BACs on how they exercise such discretion in relation to limited tenders.

A further limitation of the GPRA and the IRRs is the provision creating but limiting

the independence of a bid challenge mechanism. This will be considered in the

following in the discussion on accountability in the procurement system.

Failings in the implementation of the reforms and the prevalence of

corruption

The impact of the procurement reforms has been further undermined by failings in

their implementation by procuring entities and by weaknesses in watchdog and

enforcement bodies. As pointed out by the World Bank in its 2008 report. much

progress has been made in procurement reform in terms of rules and regulations but

implementation and enforcement are still weak, and the objectives of the reform have

not been fully achieved (World Bank, 2008, p. 45).

Closely associated with weak implementation is widespread corruption (which may

be perceived as both the cause and result of weak implementation). Despite the range of

measures introduced to combat corruption, it is still prevalent in day-to-day

procurement. Surveys conducted by three international organisations and one

domestic organisation continue to indicate widespread corruption in government

administration, including public procurement. These organisations are the World

Bank, Transparency International, World Economic Forum, and the Philippines

survey organisation, Social Weather Stations.

The World Banks measure of Control of Corruption for 2010 gave Philippines a

point score 20.82 within the range of 22.5 to 2.5, compared to a score of 20.31 in

1996, and a global percentile rank of only 22.5 compared to 44.7 in 1996 (the lower the

rank the greater the extent of corruption) (World Bank, 2011a). These scores are

corroborated by references to continuing corruption in public procurement in the

World Banks recent procurement assessment reports of the Philippines (World Bank,

2005, p. 15; World Bank, 2008, pp. 24, 40-1). The ndings by the World Bank are

supported by those of Transparency International (TI). In its Corruption Perceptions

Index in 2011, the Philippines was ranked at 129 out of 183 countries (the higher the

rank the greater the corruption), and given a score of only 2.6 out of 10. In 1999, its rank

was 54 out of 99, with a score of 3.6 out of 10. Both surveys point to a discernible

increase in corruption over the last ten years or so (Transparency International, 2011a).

These ndings are consistent with the survey of conditions affecting business

competitiveness in 139 countries conducted by the World Economic Forum and

published in The Global Competitiveness Report, 2011-2012. The survey sample in the

Philippines comprised 93 businesses, ve of which employed over 5,000 people. Four

questions in the survey focused on corruption and unethical conduct. One of the

questions was: In your country, how common is the diversion of public funds to

companies, individuals, or groups due to corruption? (1 very common; 7 never).

The average score for the Philippines was 2.3 giving it a rank of 127 out of 142 (the

higher the rank the greater the degree of corruption). In response to a second question,

How would you rate the level of public trust in the ethical standards of politicians in

your country? (1 very low; 7 very high), the rating for the Philippines was 1.8

IJPSM

26,5

390

giving it a rank of 128. In response to a third question, In your country, how common is

it for rms to make undocumented extra payments or bribes connected with imports and

exports; public utilities; annual tax payments; awarding of public contracts and licenses;

obtaining favourable judicial decisions? (1 very common; 7 never occurs), the

average rating was 3.0 giving the country a ranking of 119. The fourth question, To

what extent do government ofcials in your country show favouritism to well-connected

rms and individuals when deciding on policies and contracts? (1 always show

favouritism; 7 never show favouritism), elicited a score of 2.4 giving a ranking of 118.

The responses to this question are perhaps further evidence of the ability of business

leaders connected to powerful families to affect decisions of BACs through informal

channels in the bureaucracy. The ratings and rankings are the worst overall among the

Asian countries surveyed (World Economic Forum, 2011, pp. 392-394, 396).

Equally important are the ndings of the polls conducted by Enterprise Survey

conducted under the auspices of the World Bank. In 2009 it surveyed 1,326 rms in the

Philippines, and among those who had been involved in quotations and tenders in the

previous 12 months, 58 per cent reported they were expected to give gifts to secure a

government contract, although only 22 per cent identied corruption a major

constraint (World Bank, 2011b). A similar nding was made by the Philippine polling

organisation Social Weather Stations (SWS). In its most recent survey of corruption

conducted in 2008, 402 private sector managers were interviewed with 267 from small

and medium enterprises and 135 from large enterprises. On a four point scale

measuring the extent of corruption from a lot to none, 62 per cent of the sample

indicated that there was a lot. Nearly 50 per cent of respondents stated that almost

all/most companies in their line of business paid bribes to secure a public contract

while 41 per cent declared to having personal knowledge of public sector corruption

in their line of business in the past three months. The median amount paid as a bribe

was 15 per cent of the contract value (Social Weather Stations, 2009).

The rst two sources (Control of Corruption measure and Corruption Perception

Index) measure perceptions of corruption in general. These are a valuable but not

always precise measures of actual corruption as pointed out by a number of writers

(Olken, 2006; Johnston, 2008; Donchev and Ujhelyi, 2009). One of the limitations are

variations in the understanding of corruption from one country to another. Two other

sources, Enterprise Survey and SWS Survey, go beyond measuring general

perceptions and more directly assess knowledge and experience of specic forms of

corruption among businesses. In addition, the questions in the survey conducted by

World Economic Forum cover different aspects of corruption. All the sources are

consistent in pointing to widespread corruption.

Apart fromthe survey data, further evidence of corruption is provided by the Ofce of

the Ombudsman. According to its 2009 report, 12,736 complaints, nearly all relating to

corruption, were received, which was slightly higher than the annual average for

2005-2008 (12,427). Over 500 ofcials were subject to administrative sanctions

(dismissed, suspended, or reprimanded) with the largest number suspended (34 per cent).

In addition, in 2009, 189 criminal corruption cases involving high ranking ofcials were

led before the Sandiganbayan, with a conviction rate of only 33.6 per cent (a lower rate

than in the previous two years). A further 1,394 corruption cases involving lower level

ofcials, were led before the regular courts but conviction rate was very low at only one

tenth of the cases led (Ofce of the Ombudsman, 2009, p. 32, 46-7, 52).

Procurement

reform in the

Philippines

391

In addition, examples of corruption, including corruption in procurement, are

frequently cited by the local and trade press. For example, it was reported that the

purchase of military helicopters worth more than US$90 million was suspended in

September 2010 due to the drafting of specications to favour a particular group of

suppliers. Members of the BAC of the Defense Department were allegedly involved

with the likelihood that they would receive substantial bribes. In 2008, the purchase of

helicopters worth US$29 million, according to press reports, was also scrapped for

similar reasons, resulting in the debarment from public tenders of the Asian Aerospace

Company, the local supplier and partner of the US-based manufacturer of the

helicopters (Francis, 2010; Agence France Presse, 2010; Net Resources International,

2010).

There is little doubt that the degree of bribery, kickbacks, cronyism, and nepotism

that still exists in the Philippines continues to create major obstacles to implementing

procurement reforms. BACs, technical working groups and senior ofcials in

procuring entities often do not adhere to their professional and ethical responsibilities,

as laid down in the reforms. Procurement specications, eligibility assessments,

contractor performance measurements, and most importantly bid evaluations and

contract awards are routinely tailored to serve the interests of rms within an elite

network of businesses connected to well-established landowning families, with the

payment of bribes and kickbacks by such rms as a further incentive. Likewise, single

sourcing or negotiated procurement may be adopted as the method of procurement to

ensure a contract is awarded to a rm within the elite network, even when the

conditions under which it is permitted to all intents and purposes do not exist. In face

of this, rms outside this network nd it difcult to compete for government contracts.

Elected politicians in Congress play an important role in inuencing lucrative

contract awards in favour of companies in which they have an ownership stake or for

which they act as intermediaries. In the latter role, they are often paid bribes or

kickbacks, with the money received used for their own personal benet, or to illicitly

fund their election campaigns. The informal leverage that politicians can exercise,

often through behind the scenes deals, further ensures that the preponderance of

government contracts go to the elite network of businesses connected to powerful

families ( Johnston, 2005, pp. 137, 140-4; Quimson, 2006, pp. 12-14).

Another corrupt practice which blunts the impact of the procurement reforms is

widespread collusion among would-be bidders to rig the tender and secure the

acceptance of a high bid price, despite it being prohibited under the reforms. According

to the Philippines country procurement assessment report of 2008 by the World Bank

(2008), there is a perception that collusion or rigging of bids is common, particularly

for big ticket contracts (p. 33). As an example, the World Bank found that in two

contracts it was sponsoring in the Philippines, all the bids were suspiciously clustered

together at a high price level. Such a pattern was repeated in three separate rounds of

bidding, resulting in the rejection of the bid offers in each case. The World Bank

concluded that the analysis of the bid data presented unmistakable evidence of

collusion (World Bank, 2008, pp. 33-4). The 2008 report, mentioned previously, also

pointed to the difculties of taking action against collusion rings in the Philippines. It

cited the example of the Panaon local government unit, which in the last few years

discovered a repeated pattern of high and often identical bid offers in its tenders, but

the companies concerned have continued to bid for contracts. Despite its best efforts

IJPSM

26,5

392

the local government unit has been unable to obtain enough hard evidence for a

prosecution to be undertaken (World Bank, 2008, p. 34). Such collusion serves to

frustrate the objective of the GPRA to create an open and competitive procurement

system that ensures better value for money. However, its continued prevalence is not

surprising given the extent to which the businesses sector in Philippines continues to

be controlled by a small network of businesses linked to powerful families.

Also undermining the implementation of the reforms has been limited progress in

achieving a fully transparent system of procurement. Certainly the adoption of E

procurement through PhilGEPS, disclosure of bid outcomes, and other measures to

enhance transparency have been noticeable developments. But PhilGEPS has not been

fully availed of by procuring entities. Although most national government agencies

and local government units have now registered with PhilGEPS, a substantial minority

of government-owned or controlled corporations have not. Nor do even registered

agencies always post bid notices and contract awards on its web-site (Philippine Public

Procurement Service, 2010; Padre-Isip, 2010). The World Banks 2008 report found

from pilot surveys that the requirement to publish contract awards as well has still to

be fully complied with. Moreover, the same report noted that bid notices sometimes

provide insufcient information and instructions to prospective suppliers about the

items being procured, or insufcient online access to the bid documents (World Bank,

2008, p. 28; ADB, 2009, p. 2). An equal concern has been the failure of civil society

organisations to attend as observers BAC meetings on a regular basis, which further

undermines another key reform to enhance transparency, as will be discussed in the

following. The failure to fully observe the obligations of transparency laid down in the

reforms has enabled the continuation of the practice of behind the scenes deals to

facilitate bribery and crony transactions outside of the public spotlight.

All in all the corrupt practices mentioned previously coupled with limited

transparency have prevented the achievement of the central objective of the reforms to

create a procurement system that matches international standards based on open

competition and equal access, impartial evaluations, transparent procedures, and high

end product quality.

The question of accountability: weaknesses of the monitoring,

enforcement and bid challenge mechanisms

The implementation failings referred to previously can in part be attributed to the

limited accountability of procuring entities. This to a signicant extent is due to the

lack of effective monitoring and enforcement by watchdog institutions responsible for

overseeing the procurement process (Quah, 2003a, pp. 99-100; Quah, 2003b, pp. 244-5).

This failure has occurred in spite of the reforms to create and strengthen such

institutions, referred to previously. The World Bank procurement report of 2008, and a

Transparency International report of 2006 expressed serious misgivings about the

performance of the Commission on Audit, the Ombudsman and the Sandiganbayan

(anti-graft court). They revealed that the Commission on Audit failed to nally

determine that anomalies had occurred in the majority of procurement-related cases it

investigated (Quimson, 2006, pp. 23-4; World Bank, 2008, pp. 41-2). Of the cases that

were forwarded to the Ofce of the Ombudsman for further investigation and

prosecution, according to the World Bank report, a large number had not been acted

on, and those that had been take a very long time to bring to court. The report

Procurement

reform in the

Philippines

393

concluded that the low enforcement capacity of the Ombudsmans special prosecution

ofce and that of the courts is a major concern (World Bank, 2008, pp. 41-2). This is

supported by the low conviction rates in cases led before the Sandiganbayan, as

mentioned previously. Believed to have protected corrupt ofcials under former

President Gloria Arroyo, and to avoid impeachment proceedings by the Senate, the

Ombudsman Merceditas Gutierrez stepped down in April 2011 (Yap, 2011; Burgos,

2011). A similar lack of effectiveness has characterised the other key anti-corruption

body, the Presidential Anti-Graft Commission (PAGC) until it was abolished. Of

alleged corruption cases, 1,500 were investigated by it from 2001 to mid-2007, but in

only 10 per cent of them was punitive action taken (dismissal, suspension and

reprimand) (Quimson, 2006, pp. 29-30; Presidential Anti-Graft Commission, 2007a,

pp. 4-5; Presidential Anti-Graft Commission, 2007b, pp. 5-6).

It should be noted that the work of the watchdog and enforcement bodies is

handicapped by the absence of regular and accurate reports from procuring entities on

the procedures followed in each procurement, and the outcomes achieved. Procuring

entities either ignore requirements to compile and submit such reports, often due to a

failure to institute formal arrangements to systematically gather information on their

procurement programs and to compile and keep detailed records of each procurement.

In consequence the scrutiny of procuring entities is weakened (World Bank, 2008,

pp. 37-8; Ofce of the Ombudsman, 2009, p. 34).

In addition, the existence of a range of bodies with watchdog and enforcement

functions with respect to procurement may be counter-productive. The problem is that

they have overlapping functions, with the lines of demarcation between them not

precisely drawn. The upshot may be that when a matter arises requiring monitoring,

investigation and prosecution, no agency accepts responsibility, or the opposite, two or

more do so, resulting in conicting decisions and outcomes, or even worse the

obstruction of one agency by another as a result of institutional rivalry. Further

problems are additional bureaucratic procedures and the limited pool of personnel with

the skills of monitoring, investigation and prosecution, which are spread thinly among

several agencies, so reducing the effectiveness of each agency. The desire to streamline

government agencies with overlapping functions was cited as a reason for the abolition

of PAGC, referred to previously (Sisante, 2010).

Also undermining the monitoring of procurement practices and the proper

enforcement of procurement laws and regulations is corruption in the watchdog and

enforcement bodies themselves. How widespread this may be is difcult to tell but the

World Bank drew attention in recent reports to how corruption in the enforcement and

judicial process allowed politicians, bureaucrats and business leaders who had

allegedly engaged in corrupt practices relating to procurement, to escape prosecution