Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Examples of Business Feasibility Reports

Încărcat de

trkhan123Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Examples of Business Feasibility Reports

Încărcat de

trkhan123Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Examples of Business Feasibility Reports

A market feasibility study can assess the right location before your business launch.

Related Articles

Key Factors to Considering Business Feasibility

Examples of Business Management Reports

Feasibility Analysis for Pet Store

Examples of Business and Financial Reports

What Are Examples of Managerial Reports?

How to Write a Feasibility Report on Starting a Small Scale Fish Farm

A business feasibility study or report examines a situation whether economical, technological, operational,

marketing-related or other and identifies plans best suited to manage the situation. It may involve

approaches to cutting costs, assessing a new business location, or developing a new technological

system. The feasibility report assesses the supporting data and reasoning of each plan and provides a

recommendation of which plan to implement.

Economic Feasibility

An economic feasibility study reports on the cost factors of a proposed plan to an organization. If, for

example, an organization requires a feasibility study on its payment-processing techniques, the report

may assess the cost factors involving the functions of electronic funding, security measures and

approvals applicable to both e-commerce and regular transactions. With supporting data, the study would

make a recommendation of the benefits and areas of improvement for both types of transactions.

Operational Feasibility

An operational feasibility report focuses on the effectiveness of the function of the operations of an

organization. If a business has a global market, for example, an operational feasibility study could

examine the roles within each of its divisions both locally and in each global office. Based on the data of

the study, the report could recommend that the organization consolidate and centralize certain

departments for greater efficiency and cost-savings.

Market Feasibility

If you are setting up a new retail store the right location plays an important role in the success of your

business. A market feasibility study helps determine if your location is beneficial to your business. The

market-feasibility study inspects the surrounding community, identifies competition, lifestyle, shopping

patterns and other influences. Analysis of the data in the market-feasibility study provides the basis of

whether or not this location can drive the market for your business.

Technical Feasibility

Each business needs an information system to store data. Before a system is built, a technical feasibility

study can identify the potential challenges and problems that the system may encounter technically based

on the requirements and goals of the business. The study analyzes possible technical solutions to ensure

that the system is achievable in its effectiveness to the business. The study identifies a number of

technical options based on the business's resources and requirements and a final recommendation.

Competing with Mass Merchandisers

Mass merchandisers, particularly the discount general merchandisers such as K Mart and Wal-Mart,

are growing at a rapid rate and have captured market share from smaller competing firms. It is

possible for smaller firms to survive in such an environment, but substantial changes in operations are

usually required. This article gives background information on mass merchandisers, reports the results

of an Iowa study on the impacts of one chain, and offers suggestions to smaller firms on ways to

compete in this environment.

How the large chains operate

K Mart and Wal-Mart are fighting it out to become the number one retailer in the United States,

relegating Sears Roebuck to third place. Although both firms have been in existence roughly 30 years,

their strategies and operating methods have varied considerably.

Market size

K Mart expanded rapidly in its early years, locating in large to mid-sized towns and cities all across

the United States. The company located some stores in smaller towns, but like most national

merchandisers, its major market thrust was in the larger towns and cities. However, in recent years

(apparently in response to competition from Wal-Mart) the company has been opening stores in more

small towns.

Wal-Mart, on the other hand, initially focussed its stores in the smaller towns of the South and

Midwest. The company typically would enter a town with a comparatively large store and usually

would become the dominant retailer in town. Wal-Mart's expansion was relatively slow at first.

However, starting about 1980, the company began working its way toward the East and West coasts

in a very aggressive expansion program. Its sales grew from $1.2 billion in 1980 to $25.7 billion in

fiscal year 1990. In the late 1980s, Wal-Mart also expanded its location strategy to include stores in

larger metropolitan areas. This was usually accomplished by establishing stores in the suburban areas

surrounding the central city. The Wal-Mart Company seems to be using a tandem duo of its largest

size store (nominally 110,000 square feet) along with one of its Sam's Clubs (its membership

wholesale-type store) in this effort.

Distribution system

Both K Mart and Wal-Mart now have the most sophisticated distribution systems among all of the

retailers in the world. Wal-Mart led the way in adopting the latest scanner checkout technology (a key

part of the system), but K Mart has recently made major expenditures in this area and now has a

system similar to Wal-Mart's. Since more has been written about Wal-Mart's distribution system, it will

be described below. (See January 30, 1989, Fortune and December 14, 1989, Discount Store News,

for example.)

The heart of Wal-Mart's distribution system is its distribution center. A typical distribution center is

about one million square feet in size. It has the latest in state of the art inventory control and

materials handling equipment. A distribution center can accommodate about 150 retail stores and they

are located in a circular pattern around it. Most buying is done centrally from the company's

headquarters in Bentonville, Arkansas. Merchandise is delivered to the distribution centers and then

trucked directly to the retail stores daily. As customers make purchases, sales amounts and the

change in inventory are automatically sent to the computer by the electronic scanner checkout

system. This information is then sent daily via Wal-Mart's own satellite system to headquarters and to

the appropriate distribution center. This daily updating of inventory allows distribution centers to send

the precise amount of merchandise to the stores to maintain the optimum level of stock.

Similarly, the inventory information allows buyers to order ahead and keep the proper amounts of

goods flowing into the distribution centers. According to Discount Store News, about 78 percent of the

merchandise sold in Wal-Mart stores comes through the distribution centers. The remaining

merchandise is delivered directly from the factory or through vendors and distributors.

The efficiencies generated by this type of distribution system are enormous and play a large role in

the success of these large companies. Discount Store News reported that Wal-Mart's distribution costs

amounted to only 1.3 percent of its sales, compared to 3.5 percent for a major competing discount

chain and 5.0 percent for a major general merchandise chain. In other words, for every $100 worth of

merchandise sold, the cost of getting it from the factory to the retail store was $1.30. It is not hard to

see why smaller retailers have such a hard time competing pricewise when their merchandise must

sometimes go through multiple layers of wholesalers and distributors.

Pricing

Mart and Wal-Mart have two fundamentally different methods of pricing. K Mart has always

employed the weekly sale system, where one or two print ads per week are distributed through local

newspapers and advertisers. These sales flyers feature seasonal items and other popular items at very

attractive prices. This is the system used by most other mass merchandisers. The strategy is to get

customers into the store on the basis of attractive prices on advertised merchandise. It is then

believed that most customers will assume that all other merchandise has a low price, and will make

purchases without comparison shopping.

The weekly sale system has encountered problems over the years. For example, many customers

have had the experience of buying non-sale merchandise only to find it at a lower price at a competing

store. One of the biggest problems with the weekly sale system is that often there are quick outages

of popular items. The usual solution to this problem is to offer a "rain check," which in the unhappy

experience of many shoppers, sometimes seems to disappear down a big black hole. Another problem

is difficulty in identifying the real sale item. Many have been frustrated when discovering at the

checkout counter that they had picked up the non-sale item.

Wal-Mart's system of pricing is the "everyday low price" system. Stores do not depend on the

weekly sale incentive, but instead have cultivated the idea that everything is low priced at Wal-Mart

every day. The company did not invent the concept, but they have implemented it masterfully.

Although Wal-Mart does have occasional sales, usually seasonally, the sales do not play a large role in

their pricing strategy. Consequently, the company apparently spends less on print advertising than its

competitors. Television advertising plays a large role in Wal-Mart's marketing strategy and virtually

every ad features everyday low prices. Through advertising and word of mouth, the company has

developed a strong reputation for low prices. Many people strongly believe that everything is, in fact,

lower priced every day. People who carefully comparison shop have found that everything is not at the

lowest price at Wal-Mart everyday. However, perception is more important than reality, and most

people perceive that nearly everything has a lower price at Wal-Mart.

Merchandise mix

K Mart, Wal-Mart and other discount general merchandise stores try to promote the concept that

the average shopper can find most of his or her everyday needs under one roof at the lowest price

possible. Much of the merchandise in these types of stores is, in fact, aimed at lower income

consumers. In many states, approximately one half of the households have disposable incomes of less

than $20,000 per year, according to Sales and Marketing Management's 1990 Survey of Buying

Power. People in this income category seldom have much discretionary income and most gravitate to

stores where they perceive they are receiving the best value for the dollar. Although this segment of

the population appears to be the primary target market of the major discounters, surveys have shown

that many middle income shoppers also make purchases in these stores (see December 14, 1989,

Discount Store News).

Wal-Mart claims to have 36 departments in most of its stores. This is a wide variety of merchandise

and by necessity would include primarily fast-moving, popular items. It appears that many shoppers

have been acclimated to shopping first at the discount mass merchandisers, purchasing what they can

there, and then concluding their shopping trips at specialty stores where they purchase the remaining

items on their shopping lists.

Service

Most of the discount general merchandise stores offer minimal service as a means of reducing

expenses and maintaining lower prices. The most noticeable lack of service is in the area of expert

technical advice. Most of the people working in the departments of these stores are primarily

concerned with stocking shelves and few have enough product knowledge to offer expert advice.

There may be some exceptions in such areas as sporting goods, jewelry, pharmacy, etc., where

employees are routinely behind a counter selling, rather than stocking.

Other services normally lacking in these types of stores are gift wrapping, in-store credit, delivery,

special order, special classes, etc. However, many customers seem willing to forego these types of

services in return for lower prices.

The Iowa study

It is important that smaller retailers know the probable impact of a discount mass merchandiser on

businesses in their community. Armed with this knowledge, they are in a much better position to

make strategic decisions concerning their business. The Iowa study was conducted in order to

document what happened after a Wal-Mart opened in towns of 5,000 to 30,000. The latest study

shows results through fiscal year 1989.

Some people ask, "Why Wal-Mart? Why not K Mart or Target?" The answer is that Wal-Mart was the

only chain aggressively expanding in the state during a time period when sales tax records were

available for analysis. The results of the study do not prove causation, but strong correlations should

be taken seriously.

Data sources

Iowa Retail Sales and Use Tax Reports were used to document the sales levels of host towns and

other towns before and after Wal-Mart store openings. The reports list the sales levels for all towns

with at least 10 business firms. For towns over 2,500 population, the reports also list sales by a two

digit Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code, providing there are at least five such businesses in

a category. For example, sales are listed for categories such as building materials, general

merchandise, food, apparel, etc. Town population figures are central to this study and were taken

from the latest estimates of the United States Census Bureau.

Pull factor analysis

The raw data in these retail sales time series are based on current dollar sales. Current dollar

figures are not a very satisfactory way of analyzing the trends for towns in a state. They do not

account for price inflation, population changes or changes in a state's economy. The current dollar

sales were converted to pull factors in this study to provide a more equitable basis for comparison.

The pull factor is defined below.

PF = PST / PSS

Where: PF = Pull Factor

PST = Per capita Sales for Town

PSS = Per capita Sales for the State

For example, if a town had per capita sales of $9,000 per year and the statewide per capita sales

were $6,000 per year, the pull factor would be $9,000 divided by $6,000 = 1.5. The interpretation

would indicate that the town was selling to the equivalent of 150 percent of the town population, in

full-time customer equivalents. In other words, the pull factor is a proxy measure for the size of the

retail trade area of the town. When data are available, pull factors can be computed for the different

merchandise categories within a town and for the total sales of the town.

Comparison techniques

In this study, pull factors were computed for total sales for all towns in the state since the

establishment of the first Wal-Mart stores in 1983. Pull factors were also computed for eight

merchandise categories for towns over 5,000 population. It would have been desirable to compute pull

factors by merchandise categories for towns between 2,500 and 5,000 population, but many of them

have less than five stores in a category and consequently no sales are reported because of statutory

confidentiality rules.

For each Wal-Mart town, pull factors were established for the year preceding the opening of the

Wal-Mart store and for each year since. These were compared to the average pull factors for non-Wal-

Mart towns of a similar size (between 5,000 and 30,000 population) and to pull factors for larger

towns (over 30,000 population) for the same time periods. Comparisons were also made to the total

sales pull factors for towns below 5,000 population in the same time period.The net result is a broad

look at the change in trade area sizes for stores in different merchandise categories in the host towns

and in other competing towns. It cannot be stated conclusively that Wal-Mart stores caused all the

changes in trade area size, since other variables are always interacting to cause changes. However,

when significant changes are seen to be consistently correlated with the opening of Wal-Mart stores,

one can draw solid conclusions in spite of the lack of more sophisticated statistical techniques.

Findings

The study found both pluses and minuses for the merchants in the host town. The major plus for

most businesses was that in virtually all cases, total sales in the town increased at a rate greater than

average for the state. Apparently, Wal-Mart stores attracted customers into town from a greater

radius than had occurred before their entry into town. Two simple rules of thumb explain the winners

and losers among host town merchants.

Table 1: Sales Change in Wal-Mart Towns versus Same Size Towns (% cumulative)

Business Type

Wal-Mart Towns

After Years

Same Size Towns*

After Years

1 3 5 1 3 5

Building Materials -6.3 -6.5 -5.1 -4.7 -7.1 -10.4

General Merchandise 29.1 39.5 58.8 -0.6 -4.2 -1.9

Food -4.7 -4.1 -12.1 1.6 5.5 7.8

Apparel -2.7 -6.2 -5.1 -3.5 -5.8 -11.5

Home Furnishing 2.9 5.2 4.2 -5.1 -12.2 -18.9

Eating & Drinking 0.8 -0.8 2.4 -0.7 -1.5 -0.8

Specialty -5.7 -12.1 -19.7 0.1 -5.4 -9.9

Services -5.6 -7.9 -6.8 -3.5 -9.5 -14.2

TOTAL SALES 2.3 3.1 8.1 -0.7 -3.5 -4.9

* Did not have a Wal-Mart store.

Rule 1: Merchants selling goods or services that Wal-Mart does not sell become natural

beneficiaries. In other words, since they are not competing directly, many of them benefit from the

spill over of the extra customers being pulled into town by Wal-Mart.

Rule 2: Merchants selling the same goods as Wal-Mart are in jeopardy. In other words, they are

subject to losing some trade to Wal-Mart unless they change their way of doing business.

A basic premise lies at the heart of this study. The premise is that in areas of relatively static

population (such as in states like Iowa) the size of the retail "pie" is relatively fixed in size for a given

geographical area. Consequently, when a well-known national chain like Wal-Mart opens a large store

in a relatively small town, it invariably will capture a substantial slice of the retail pie. The end result is

that other merchants in the area will have to make do with smaller slices of the retail pie, or get out of

business. In areas of the country where the population is growing rapidly, there is room for more retail

establishments and the effect will be diluted considerably.

Table 1 compares the cumulative real percentage change in retail sales for businesses in Iowa Wal-

Mart towns to those of businesses in the same size non-Wal-Mart towns. It should be noted that this

data is reported by type of store and not by exact lines of merchandise.

Host towns (Wal-Mart towns)

As shown in Table 1, there are winners and losers among merchants in a host town after a Wal-

Mart store locates there. Data were available for 17 towns that had a Wal-Mart store for at least one

year, 14 towns that had one for at least three years, and five towns that had one for at least five

years. Caution should be used in interpreting the five-year figures since the sample is so small.

Winners

The general merchandise category shows the greatest gains in sales after a Wal-Mart store opens in

a town. However, it will be shown later that most of this gain is by the Wal-Mart store and, in fact, the

competing general merchandise stores usually sustain a loss of sales.

The home furnishings category shows a real net gain of 5.2 percent after three years. This category

consists of furniture stores, major appliance stores, floor covering stores, drapery stores, etc. Neither

Wal-Mart nor most of the other discount general merchandise stores handle much of this merchandise,

therefore these merchants are the natural beneficiaries referred to in rule of thumb 1.

Eating and drinking establishments fluctuate between slight gains and slight losses after a Wal-Mart

store opens. My study last year showed larger gains in these types of firms. It was concluded that

because more customers were coming into town, some were staying long enough to consume meals.

Other non-competing businesses spanning a wide gamut could also benefit from the additional

traffic brought to town by a Wal-Mart store.

Losers

As shown in table 1, the specialty category of stores shows the greatest reduction in sales with an

average real decrease of over 12 percent after three years. Specialty stores encompass a great

number of stores such as drug stores, sporting goods, card and gift shops, fabric stores, jewelry

stores and others. Many of these stores would be competing head to head with a major department

within one of the major discount stores. Building materials stores lost an average of 6.5 percent of

their sales after three years. The building materials category consists primarily of lumber yards,

hardware stores, and paint and glass stores. Most of the evidence points to hardware stores suffering

the brunt of these losses, since they are selling many of the same items that the discount stores

carry.

Apparel stores suffered sales reductions of 6.2 percent after three years. The apparel category

consists of various clothing stores and shoe stores. It is usually assumed that most of these sales

reductions occur among the stores selling low end merchandise.

Food stores (grocery stores) also show an average 4.1 percent reduction in sales after three years

of Wal-Mart operation. This is a surprise to many people. An analysis of purchases in Iowa food stores

shows that between one quarter and one third of the purchases in grocery stores are non-food items,

such as health and beauty aids, cleaning supplies, paper products and pet supplies. It appears that

many consumers merely transfer the purchase of these types of items from the grocery store to a

nearby discount store.

The services category shows a sales reduction in both Wal-Mart towns and similar size towns

without Wal-Mart stores. This category is weighted heavily by hotels/motels, theaters, etc. When

compared to the cities, it appears that these types of businesses are declining in most smaller towns.

Total sales for towns with Wal-Mart stores were up a cumulative 3.1 percent more than the state

average after three years.

Same size towns

Over 30 towns with a population in the 5,000 and 30,000 range, where there was no Wal-Mart

store, were analyzed for the same years and in the same manner as were the Wal-Mart towns. The

results are shown below.

Winners

The same size towns (5,000 to 30,000 population) in the state without Wal-Mart stores showed

gains of 5.5 percent in food store sales after three years. This was the only category to show gains.

Over one third of the grocery stores in the state have gone out of business in the last 12 years. These

failures have occurred mainly in towns that had fewer than 1,000 people. When a small town loses its

grocery store, residents then have to travel to a nearby larger town to shop. The towns in the 5,000

to 30,000 population class have been the primary beneficiaries of this additional grocery trade.

Losers

Home furnishings stores suffered the largest losses of trade. There has been an ongoing trend of

more and more home furnishings trade going to bigger cities.

Specialty stores in the non Wal-Mart towns suffered some loss of sales (5.4 percent after three

years), but not nearly as much as the Wal-Mart towns.

Other types of stores in the non Wal-Mart towns suffered roughly the same percentage losses of

sales as did the Wal-Mart towns. Total sales, however, were nearly a mirror image and were down 3.5

percent after three years of Wal-Mart competition.

Netting out sales

To get a better idea of the internal impact of a Wal-Mart store on a host town, it is useful to "net

out" the sales. Basically, this means making an estimate of the Wal-Mart store's sales. It was

estimated that for the average town in Iowa, Wal-Mart sales were $13 million last year. Figure 1

shows the netting out process based on this estimate and actual sales changes for all other

businesses.

Based on Figure 1, the following conclusions can be made:

If the Wal-Mart store had sales of $13 million and the total sales of the town only increased by

$4 million, then there had been a total reduction of sales in the town of $9 million for existing

merchants.

If the Wal-Mart store had sales of $13 million and the general merchandise category (of which

it is a part) increased by only $7 Million, then existing general merchandise dealers suffered

sales reductions of $6 million.

If general merchandise stores accounted for $6 million of the total $9 million reduction, then

the net reduction in sales for other existing merchants must have been $3 million.

Small towns

Four smaller towns within a 20 mile radius of each Wal-Mart town were compared to all other

similar size towns further away from Wal-Mart towns. Figure 2 on page 39 shows the results over four

years. It is fairly obvious that nearby small towns lose trade more rapidly than other towns. After four

years, the towns within a 20-mile radius of a Wal-Mart store had cumulative net sales reductions of

23.5 percent while the same size towns much further away had sales reductions of only 10.8 percent.

Larger cities

At the time of this study, there were no Wal-Mart stores in cities above 50,000 population in Iowa,

although they are currently entering. There were only two areas where the cities appeared to be

affected by Wal-Mart stores in the surrounding areas. General merchandise sales were down nearly 7

percent and grocery store sales were down nearly 3 percent after three years of Wal-Mart stores. The

apparent major reason for these reductions is that local residents have to make fewer trips to the

cities to shop.

Strategies for co-existing in a discount mass merchandiser

environment

Many small retailers will need to develop new business strategies after a Wal-Mart store or other

discount mass merchandiser opens in their area. The following suggestions are based on extensive

observations in Iowa and study of situations in other states.

Attitudes and actions

In general it is best to take a positive attitude toward the opening of a new mass merchandise store

in your area. The following thoughts are offered in this regard. In a free enterprise economy, all firms

are free to compete. However, local officials should be careful not to offer unduly generous incentives

to large firms that could place smaller firms at a disadvantage.

Recognize that a discount mass merchandise store will probably enlarge your town's retail trade

area size. Try to figure out ways to capitalize on the increased volume of traffic to town.

It is possible to co-exist in this type of environment.

You may need to change your methods of operation as described below.

Merchandise tips

The following suggestions are offered with regard to merchandise mix.

Try not to handle the exact same merchandise. For example, at least three of the largest mass

merchandisers sell a particular brand of men's jeans for around $10. I have seen cases where

smaller merchants sell the same brand jeans for $14. Customers automatically detect that the

smaller merchant is 40 percent higher priced and often assume that everything else in the

store is 40 percent higher. A better strategy would be to sell another brand that is not directly

comparable.

Sell singles instead of pre-packaged groups. Mass merchandisers often sell pre-packaged

merchandise that contain multiple items. Customers often need only one item. Independent

merchants can often meet these needs by unbundling packages and selling items as singles.

For example, a crafts store may gain new customers and make more profit by selling singles

of various supplies such as templates, paint brushes, etc. Try to handle complementary

merchandise. In many departments (such as hardware, electrical, plumbing, lawn and garden)

the mass merchandisers handle only fast-moving merchandise. Astute competing merchants

should expand their lines to be more complete than their giant competitors. Customers will

soon learn to go directly to the more complete store if their needs are out of the ordinary. For

example, a customer building a back yard storage shed requiring 15 pounds of nails and 100

bolts will be sadly disappointed if he or she shops at a discount general merchandiser and

finds only small pre-packaged assortments. Their needs will be much better met by a

hardware store that has a wide assortment of these items in bulk quantities.

Look for voids in the mass merchandiser's inventory. For example, most discount general

merchandisers do not handle the higher-priced name brand athletic shoes desired by so many

people today. A smart competing sporting goods dealer would handle a full line of better

athletic shoes. Consider upscale merchandise. Not all customers desire or demand lower-

priced merchandise. For example, there are cases of smaller children's wear stores which

prosper in the shadow of a discount general merchandiser by catering to the tastes and

preferences of middle-to-upper income clientele and to the "grandparent trade" where money

is often not as much of a factor.

Find a niche that you can fill. Smaller merchants can often succeed by merely finding the

various voids in the mass merchandisers' inventory and filling them as described above.

Marketing tips

There is always room for improving marketing practices. The following tips are offered to merchants

regardless of their competition.

Extended opening hours are a necessity! Lifestyles have changed dramatically in the last

generation. Now it is quite common for a household to have multiple wage earners working

outside the household. Most of these people simply cannot get to local stores that stay open

only from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Downtown merchants and other independent merchants

cannot seriously compete in this environment unless they cooperate and offer similar

convenient opening hours.

Look for ways to improve your returns policies. Most mass merchandisers have very liberal

returns policies. Unfortunately, many smaller independent merchants cannot offer comparable

policies because of their lack of leverage with major suppliers. In the long run, they need to

work through trade associations and buying groups to achieve comparable leverage with

suppliers. In the short run, they need to use common sense. For example, if a customer

purchases a piece of lawn equipment in May and brings it back shortly because of a

malfunction that required factory repair, the dealer would be well advised to give the customer

a new replacement immediately (or at least offer a loaner) until the repaired item is returned.

I know of a case where the customer was left empty-handed until the repaired item finally

came back in August. Needless to say, he was not happy.

Sharpen your pricing skills. (Eg; lower prices on items that people purchase frequently.) It is

my contention that many consumers do not know the "going price" of much of what they buy.

They tend to know the price of the things they purchase frequently, or the things they have

seen advertised recently. Discount mass merchandisers recognize this and tend to focus their

lowest prices on these items. The average consumer then assumes that prices on all other

items must also be less. Conversely, many local merchants have gotten a "bad rap" on price

image when they have not been careful in pricing some of the "hot items." Independent

merchants need to determine which items customers tend to know the price of and make

special efforts to keep these prices competitive.

Focus your advertising. Stress your competitive advantage. Every business must have one or

more competitive advantages in the eyes of the customer in order to succeed. For example,

Sears established a huge competitive advantage when it adopted "Satisfaction Guaranteed"

many years ago. With Wal-Mart, "Everyday Low Prices" is a strong competitive advantage.

Large firms incorporate these competitive advantages into nearly every advertisement.

Unfortunately, many smaller merchants do not get their full money's worth from their ads

because they often fall to promote their competitive advantages. For example, a drug store

with 24-hour prescription service and free delivery ought to incorporate those facts into every

ad. Likewise, an apparel store that features special orders and in-store credit should stress

those features in its ads.

Service tips

Superior service can become an important competitive advantage for many smaller businesses.

Large chain stores usually don't have the flexibility to offer many of these services.

Emphasize expert technical advice. It Is difficult to find workers in discount mass merchandise

stores who know the merchandise. There are many examples of smaller merchants who build

a loyal clientele because they are able to help customers analyze their problems and help

them find the right tools, supplies and equipment.

Offer deliveries where appropriate. A certain segment of our population has a need for the

delivery of prescription drugs or heavy equipment. Typically, mass merchandisers cannot

respond to these needs. Some smaller merchants can carve out a certain market share by

offering delivery service.

Offer on-site repair of certain items. Nearly everyone has a need to have some item repaired

or serviced occasionally. Larger discount stores usually cannot readily provide this service.

Independent merchants can draw a substantial volume of trade to their stores by providing

repairs and service of merchandise.

Develop special order capability. It is not possible for merchants to carry every conceivable

item in inventory. However, they can make arrangements with certain suppliers or cooperating

partner stores to priority ship needed items. Fax machines and express delivery services are

making this feasible today. So instead of letting a customer walk out the door when an item is

not inventory, it is better to say, "I'm sorry I do not have it in stock, but I can get it for you in

two days."

Offer other services as appropriate. Independent merchants can develop many loyal

customers by offering "how to do it" classes, gift wrapping, rentals of items that will boost

sales of collateral merchandise, etc.

Customer relations tips

In past years, small businesses had the reputation of excellent customer relations. However,

nowadays many consumers perceive that they are treated no better in small firms than in larger ones.

Research has shown that poor customer relations is the primary reason that customers quit doing

business with a store. The following suggestions are offered for all businesses.

Make sure customers are "greeted. " According to surveys in Iowa, customers are very

offended by the failure to be greeted or acknowledged when entering a store. This is

particularly true when the customer is in a buying mood. All store personnel should be trained

to greet customers.

Offer customers a smile instead of a frown. All customers prefer to do business where they are

treated in a friendly manner.

Make employees "associates." Firms like Wal-Mart and J. C. Penney call their employees

associates and treat them as part of the team. Independent merchants can emulate this.

Regular store meetings could be held where everyone can participate in planning and problem

solving.

Solicit complaints. Many times customers have a bad experience in a store, but they are

reluctant to complain to store personnel. Instead, they complain to other people. Good

merchants would rather hear of the complaint first so they can find a remedy. They can

provide an environment where customers feel comfortable in complaining by soliciting

complaints through ads, through signs at the checkout counters, and by signs on shopping

bags.

Train employees often. In the eyes of the customer, the employee is the business. Training

employees can have one of the highest payoffs of any investment in the business. Training is

available through Small Business Development Centers, university extension services,

community colleges, parent companies, franchisors, and others. Also, there is a wide array of

video tapes available today where training can be conducted in the store.

Summary and conclusions

When a discount mass merchandise store opens in a small-to medium-size town with little

population growth, there will be both positive and negative effects. The total retail trade area size will

expand. There will be some beneficial "spill over" sales that accrue to some firms (primarily

restaurants, home furnishings stores, building materials firms, and other noncompeting firms).

However, other existing merchants may suffer losses of sales unless they make adjustment to

compete in the new environment. In Iowa, competing general merchandise firms have suffered the

greatest losses, while specialty stores, service firms, and apparel stores also suffered substantial

decreases in sales.

Towns of a similar size without a large mass merchandiser have suffered sales losses in home

furnishings, service firms, building materials, and apparel, that are partially attributable to the

discount stores nearby towns.

The largest towns and cities continue to gain sales in all categories except general merchandise and

groceries. Since these are trend reversals, it appears that discount mass merchandise stores are

holding customers in the local area to shop for general merchandise to a greater extent than before,

thereby causing fewer shopping trips to the city.

The smallest towns suffer at the hands of all the larger towns and cities. The best strategy for

merchants in these towns is to get back to the basics of running a good business and focus on making

service a strong competitive advantage.

The major conclusion reached from this study and analysis is that it is possible to coexist in the face

of competition from discount mass merchandisers. There are many documented cases of merchants

surviving and in some cases thriving when operating against such formidable competition. However,

most of these merchants did not continue business as usual. They made many of the changes

suggested above, including major changes in merchandise mix.

- Kenneth E Stone, Ph.D. Source: The Journal of the Association of Small Business Development Centers This article is

reprinted from the Small Business Forum, the journal of the Association of Small Business Development Centers.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Marketing Assignment BSBMK609 PDFDocument14 paginiMarketing Assignment BSBMK609 PDFArslan ImdadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of The Product and Destination Image of BrightonDocument12 paginiAnalysis of The Product and Destination Image of BrightonDani QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Raising Sheep Farm ManagementDocument5 paginiRaising Sheep Farm ManagementMoises CalastravoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hotel Cost Centres & BudgetsDocument5 paginiHotel Cost Centres & BudgetsPahn PanrutaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- College of Business, Hospitality and Tourism Studies: Name: IDDocument5 paginiCollege of Business, Hospitality and Tourism Studies: Name: IDMr. Sailosi KaitabuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solved Forecasting The Success of New Product Introductions Is Notoriously DifficultDocument1 paginăSolved Forecasting The Success of New Product Introductions Is Notoriously DifficultM Bilal SaleemÎncă nu există evaluări

- BUSINESS PLAN - Ramalivhana Poultry FarmDocument32 paginiBUSINESS PLAN - Ramalivhana Poultry FarmNeo Ramalivhana100% (1)

- BIBINGKINITANDocument6 paginiBIBINGKINITANRhayne BalmacedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Can T We Pay Our Shareholders A Dividend Shouts YourDocument2 paginiWhy Can T We Pay Our Shareholders A Dividend Shouts YourMiroslav GegoskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Book of Revelation, Review, Part 3Document6 paginiThe Book of Revelation, Review, Part 3Grace Church ModestoÎncă nu există evaluări

- B205A - FTHE Spring 2020-2021Document5 paginiB205A - FTHE Spring 2020-2021Kareem Nabil0% (1)

- International Marketing OpportunitiesDocument12 paginiInternational Marketing OpportunitiesGagandeep BansalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manage budgets and financial plans assessmentDocument11 paginiManage budgets and financial plans assessmentcseiji20% (5)

- Business Plan Proposal for Mars Cafe & Restaurant in BueaDocument12 paginiBusiness Plan Proposal for Mars Cafe & Restaurant in BueaSophia EbobÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swot Matrix - AMANDocument1 paginăSwot Matrix - AMANmedai lehÎncă nu există evaluări

- BSBMGT605B - Assessment Task 2Document7 paginiBSBMGT605B - Assessment Task 2Ghie MoralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Marriot HotelDocument69 paginiHistory of Marriot HotelFarrukh KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liberty Restaurant Group Business Plan ExtractsDocument5 paginiLiberty Restaurant Group Business Plan ExtractsnehaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BSBMGT617-Appendix 1 - WorkChairs Case StudyDocument39 paginiBSBMGT617-Appendix 1 - WorkChairs Case StudyNarmeen SohailÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accounting Devoir Part BDocument2 paginiAccounting Devoir Part BAbdul HadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Managing Financial Resources and DecisionsDocument28 paginiManaging Financial Resources and DecisionsamyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essay: Privatization of MedicineDocument8 paginiEssay: Privatization of MedicineMuhammad Dzaky Alfajr DirantonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Charity-Care: Research Plan: BSBCOM 603 - Plan and Establish Compliance Management Systems Task 1Document14 paginiCharity-Care: Research Plan: BSBCOM 603 - Plan and Establish Compliance Management Systems Task 1Ashna WaseemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dark Roast JavaDocument59 paginiDark Roast Javajpauno201250% (2)

- Week 2 Workshop SolutionsDocument6 paginiWeek 2 Workshop SolutionsJenDNg50% (2)

- t1 CPCCPD2011 - Handle - and - Store - Painting - and - Decorating - Materials - Assessment - Booklet PDFDocument55 paginit1 CPCCPD2011 - Handle - and - Store - Painting - and - Decorating - Materials - Assessment - Booklet PDFAisha AnwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Part B - CritiqueDocument3 paginiPart B - CritiqueSrijeeta De100% (1)

- Revised Briefing Report Briefing Report Naturecare Products Marketing Briefing ReportDocument2 paginiRevised Briefing Report Briefing Report Naturecare Products Marketing Briefing ReportnattyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Format of Feasibility StudyDocument10 paginiFormat of Feasibility StudyHanna RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supply Chain DriversDocument26 paginiSupply Chain DriversHaris AlviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Palakipac's Powdered Jute Ltd. Projected Statement of Comprehensive Income 2017-2021Document5 paginiPalakipac's Powdered Jute Ltd. Projected Statement of Comprehensive Income 2017-2021Lailani KatoÎncă nu există evaluări

- BSBLDR803 Partnership Task 1 Akash KaileyDocument18 paginiBSBLDR803 Partnership Task 1 Akash Kaileysuper neoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment HI6026.1 T1 2016Document2 paginiAssignment HI6026.1 T1 2016Abs PangaderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bsbops601 - Week 4Document13 paginiBsbops601 - Week 4Natti NonglekÎncă nu există evaluări

- BFM205 Week 1Document33 paginiBFM205 Week 1Nishant ShahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment I - Marketing StrategiesDocument22 paginiAssessment I - Marketing StrategiesDani LuttenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principle of Marketing - Project On Deewan Sweets, Shikarpur, SindhDocument13 paginiPrinciple of Marketing - Project On Deewan Sweets, Shikarpur, SindhKhair MuhammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- BSBRSK501 - A2 - AnushaDocument9 paginiBSBRSK501 - A2 - AnushaanushaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11 Chapter III Marketing AspectDocument37 pagini11 Chapter III Marketing AspectAzkaliverÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pre-Assessment of Feasibility StudyDocument3 paginiPre-Assessment of Feasibility StudyCresca Cuello CastroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coffeeville: Marketing ProposalDocument10 paginiCoffeeville: Marketing ProposalPattaniya KosayothinÎncă nu există evaluări

- KIAN Internship Final ReportDocument16 paginiKIAN Internship Final ReportNaLfieÎncă nu există evaluări

- How SCI innovation can reduce Coffee Rome's carbon footprintDocument6 paginiHow SCI innovation can reduce Coffee Rome's carbon footprintJoanne Navarro Almeria100% (1)

- Profile PDFDocument16 paginiProfile PDFAndriGunawanSaputraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case StudyDocument5 paginiCase StudygurlalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hote Business Plan AssignmentDocument49 paginiHote Business Plan AssignmentPeter OgollaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Data Management Proposal for SchoolDocument3 paginiData Management Proposal for SchoolJyoti Devi0% (1)

- BSBRES801 - Student Assessment Task 1, Task 2 PDFDocument11 paginiBSBRES801 - Student Assessment Task 1, Task 2 PDFMohsin Akram20% (5)

- BSBFIM601 Powerpoint PresentationDocument94 paginiBSBFIM601 Powerpoint PresentationJazzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Research Writing GuideDocument6 paginiBusiness Research Writing GuideCharmaine ShaninaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Break-Even Point (BEP) Is The Point at Which Cost orDocument18 paginiBreak-Even Point (BEP) Is The Point at Which Cost orManav HnÎncă nu există evaluări

- MN3042QA Assignment Brief 3 With Grading SchemeDocument5 paginiMN3042QA Assignment Brief 3 With Grading SchemeleharÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2b Format of Marketing PlanDocument3 pagini2b Format of Marketing PlanManthan KulkarniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Provide Leadership Across The Organisation BSBMGT605: Mohammad Fayzul Hassan Chowdhury Student Id: Ts823Document16 paginiProvide Leadership Across The Organisation BSBMGT605: Mohammad Fayzul Hassan Chowdhury Student Id: Ts823fhc munnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hints 7.06.17 Assessment - BSBMKG507 Interpret Market Trends and Developments-1-2Document12 paginiHints 7.06.17 Assessment - BSBMKG507 Interpret Market Trends and Developments-1-2Arifur rahman0% (1)

- 1 SceneDocument7 pagini1 SceneprecillaugartehalagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Krispy Kreme Doughnuts 10am To 1130am 1Document51 paginiKrispy Kreme Doughnuts 10am To 1130am 1beeeeee100% (1)

- Coffee ShopDocument14 paginiCoffee ShopAgustinÎncă nu există evaluări

- BSBMKG506Document5 paginiBSBMKG506wipawadee kruasang100% (1)

- Value Chain Management Capability A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionDe la EverandValue Chain Management Capability A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- U of Regina 2022-23 graduate tuition and mandatory feesDocument1 paginăU of Regina 2022-23 graduate tuition and mandatory feestrkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- Windsor University Canada Fees Tuition Fee Estimator - Finance DepartmentDocument1 paginăWindsor University Canada Fees Tuition Fee Estimator - Finance Departmenttrkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- English: Aligarh Institute of Technology, KarachiDocument1 paginăEnglish: Aligarh Institute of Technology, Karachitrkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- 75 Greatest Motivational Stories Ever Told! PDFDocument110 pagini75 Greatest Motivational Stories Ever Told! PDFEsther Parvu88% (24)

- EZCAD 2.7.6 Software Manual PDFDocument141 paginiEZCAD 2.7.6 Software Manual PDFtrkhan1230% (1)

- Travel Now Ramadan Umrah Packages 2017 1438hDocument12 paginiTravel Now Ramadan Umrah Packages 2017 1438htrkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- TYKMA Laser Marking Manual REV214Document30 paginiTYKMA Laser Marking Manual REV214dorin1758100% (1)

- Creamy Macaroni 'N' Cheese Recipe: IngredientsDocument1 paginăCreamy Macaroni 'N' Cheese Recipe: Ingredientstrkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- Indices and LogarithmDocument11 paginiIndices and Logarithmtrkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- KaizenDocument6 paginiKaizennikhilrane91_7522800Încă nu există evaluări

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pagini6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

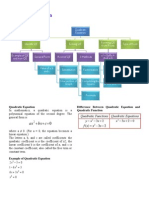

- Quadratic Equation: Ax BXCDocument9 paginiQuadratic Equation: Ax BXCMalaysiaBoleh98% (56)

- TOEFL Speaking - Question 1&2 TopicsDocument8 paginiTOEFL Speaking - Question 1&2 TopicsSiddharthaSidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Full Namaz With Urdu TranslationDocument1 paginăFull Namaz With Urdu Translationtrkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- Final Iped Ecommercereport Corrected Jan2010Document43 paginiFinal Iped Ecommercereport Corrected Jan2010trkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- Feasibility Study of Initiation of Electronic Commerce in Mazandaran Export Agencies by Using of AHP-FUZZY TechniqueDocument9 paginiFeasibility Study of Initiation of Electronic Commerce in Mazandaran Export Agencies by Using of AHP-FUZZY Techniquetrkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- 01 MAY'13 Price List11Document2 pagini01 MAY'13 Price List11trkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- List of Diploma of Associate EngineerDocument9 paginiList of Diploma of Associate EngineerArish Khan0% (1)

- Role of Supply Chain ManagersDocument30 paginiRole of Supply Chain Managerstrkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- Et 6Document4 paginiEt 6trkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- 01 MAY'13 Price List11Document2 pagini01 MAY'13 Price List11trkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- Role of Supply Chain ManagersDocument30 paginiRole of Supply Chain Managerstrkhan123Încă nu există evaluări

- CSC 1Document24 paginiCSC 1Nithesh NitheshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Department portal feasibility analysisDocument2 paginiDepartment portal feasibility analysisShaller TayeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Product Design and Manufacturing - R.C. Gupta, A.K. Chitale (PHI, 2011) PDFDocument539 paginiProduct Design and Manufacturing - R.C. Gupta, A.K. Chitale (PHI, 2011) PDFRogie M BernabeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mpe 506 NotesDocument14 paginiMpe 506 NotesFancyfantastic KinuthiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parallel Test Technology: The New Paradigm For Parametric TestingDocument66 paginiParallel Test Technology: The New Paradigm For Parametric Testinglusoegyi 1919Încă nu există evaluări

- Operational/Financial Analysis SummaryDocument13 paginiOperational/Financial Analysis SummaryKenneth Delos SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethiopian TVET Business Opportunity GuideDocument123 paginiEthiopian TVET Business Opportunity GuideAbel ZegeyeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cyber Law and Security: UNIT-3Document48 paginiCyber Law and Security: UNIT-3Vishal GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beauty Project Report Format 11-1-2 2Document47 paginiBeauty Project Report Format 11-1-2 2Anupa KhaniyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine Government Procurement SystemDocument7 paginiPhilippine Government Procurement Systemdaniel naoeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Astm Value Engineering Value Analysis E1699.4166Document8 paginiAstm Value Engineering Value Analysis E1699.4166lucioprovenzaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smart Travelling CompanionDocument54 paginiSmart Travelling CompanionAmaonwu OnyebuchiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guidance Note: Capital Works Management FrameworkDocument74 paginiGuidance Note: Capital Works Management FrameworkAsh Dark Knight7Încă nu există evaluări

- Entrp MCQs 1-3Document39 paginiEntrp MCQs 1-3Afzal Rocksx75% (8)

- OutlineDocument6 paginiOutlineIce LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pedro PP & BLDG Laws PreboardDocument61 paginiPedro PP & BLDG Laws PreboardSeiv VocheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Procurement Planning and MonitoringDocument53 paginiProcurement Planning and MonitoringIngrid Caobleclolal85% (13)

- PBO01 Principles of Business Operations 1/ Berico 1Document9 paginiPBO01 Principles of Business Operations 1/ Berico 1MarjÎncă nu există evaluări

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Roads Quality ManualDocument46 paginiFederal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Roads Quality Manualsam100% (8)

- Cevirgen 2021 - Investment Feasibility Study For Factory Planning ProjectsDocument11 paginiCevirgen 2021 - Investment Feasibility Study For Factory Planning ProjectsdemonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project Feasibility Report: BBA 5th SemesterDocument15 paginiProject Feasibility Report: BBA 5th SemesterChandan RaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report 6Document38 paginiReport 6Kulveer singhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rochester Area Vanpool Feasibility StudyDocument52 paginiRochester Area Vanpool Feasibility StudyRochester Democrat and ChronicleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Irrigation Engineering - PCJDocument276 paginiIrrigation Engineering - PCJSamundra LuciferÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project Report On Real EstateDocument74 paginiProject Report On Real EstatePriyanshu Koranga46% (13)

- ProposalDocument14 paginiProposalMiki AberaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Feasibility StudyDocument6 paginiFeasibility StudyFeven FevitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fleet Strategy ProposalDocument15 paginiFleet Strategy ProposalBheki MhlongoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Innovation Management GlobalDocument2 paginiInnovation Management Globalvaksoo vaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advanced Software Engg Notes Unit1-5Document155 paginiAdvanced Software Engg Notes Unit1-5Bibsy Adlin Kumari R75% (4)