Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Paper Niño Analisis Modelos

Încărcat de

Camila Araneda Reyes0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

19 vizualizări7 paginiThe purpose of this investigation is to determine the changes in the maxillary and mandibular tooth size-arch length relationship. An attempt was made to determine whether TSALD in the permanent dentition can be predicted in the deciduous dentition.

Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentThe purpose of this investigation is to determine the changes in the maxillary and mandibular tooth size-arch length relationship. An attempt was made to determine whether TSALD in the permanent dentition can be predicted in the deciduous dentition.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

19 vizualizări7 paginiPaper Niño Analisis Modelos

Încărcat de

Camila Araneda ReyesThe purpose of this investigation is to determine the changes in the maxillary and mandibular tooth size-arch length relationship. An attempt was made to determine whether TSALD in the permanent dentition can be predicted in the deciduous dentition.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 7

Changes in tooth si ze-arch length relationships from

the deciduous to the permanent dentition: A

longitudinal study

Samir E. Bishara, BDS, D. Ortho., DDS, MS," Paymun Khadivi, DDS, ~ and

Jane R. Jakobsen, BA, MA

Iowa Ci~ Iowa, and Pittsfield, Mass.

The purpose of this investigation is to determine the changes in the maxillary and mandibular tooth

size-arch length relationship (TSALD) after the complete eruption of the deciduous dentition

(,X age = 4.0 years) to the time of eruption of the second molars (X age = 13.3 years). In addition,

an attempt was made to determine whether TSALD in the permanent dentition can be predicted

in the deciduous dentition. Records on 35 male and 27 female subjects were evaluated. Each

subject had a clinically acceptable occl usi on-t hat is, a normal molar and canine relationship, at the

time of eruption of the deciduous and permanent teeth. In addition, each subject had a complete

set of data at the two stages of dental development. These selection criteria limited the number of

subjects in this investigation to 62. The mesiodistal diameter of all deciduous teeth and their

permanent successors, as well as various dental arch width and length parameters, were measured

in the deciduous and permanent dentitions. A total of 68 parameters were measured or calculated.

Student t tests were used to determine whether significant differences were present between the

right and left sides for both male and female subjects. Correlation coefficients r were performed

between the deciduous and the corresponding permanent teeth and also for the arch length

parameters, as well as TSALD in the two dentitions. Significance was predetermined at the 0.05

level of confidence. Stepwise regression analysis (R 2) was used to determine which of the variables

in the deciduous dentition could be included in a regression model to determine associations

between maxillary and mandibular TSALD in the permanent dentition. The results of the correlation

coefficients (r) indicate that there are a number of significant correlations between the various

variables in the deciduous and the permanent dentitions, but most of these correlations were

relatively low (<0.7), with the exception of those for the incisors, in the female subjects. The

Multiple Regression Analysis did not significantly improve the predictive abilities. Discriminant

Analysis indicated that the predictive accuracy, i.e., the percentage of cases correctly classified by

the prediction equations were, in general, relatively low. In conclusion, the changes in the alignment

of the teeth were primarily the result of a decrease in the available arch length in both the maxillary

and mandibular arches. The correlations between the various deciduous and permanent

parameters are of such a magnitude that does not allow an accurate prediction of the TSALD in the

permanent dentition from the available dental measurements in the deciduous dentition. The clinical

implications of the findings were discussed. (AM J ORTHOD DENTOFAC ORTHOP 1995;108:607-13.)

One of the most perplexing phenomenon

in orthodontics is the crowding of anterior teeth

before, as well as after the completion of orthodon-

tic treatment.

Incisor crowding can be observed in both the

young and adult dentitions. Van der Linden 1 clas-

sifted crowding on the bases of its cause as primary,

aProfessor. Orthodontic Department, College of Dentistry, University of

Iowa.

bResearch Associate; Currently in private practice.

CAssistant Professor, Department of Preventive and Community College

of Dentistry, College of Dentistry, University of Iowa.

Copyright 1995 by the American Association of Orthodontists.

0889-5406/95/$5.00 + 0 S/1/56506

secondary, and tertiary. He defined primary crowd-

ing as an inherent discrepancy between tooth size

and the available arch length, mainly of genetic

origin. Secondary crowding is caused by environ-

mental factors influencing the dentition, such as

caries and extractions. Tertiary crowding or late

crowding occurs in the postadolescent period.

The incidence of mandibular incisor crowding

was found by Barrow and White 2 to increase from

14% at age 6 to 51% at 14 years of age. Cryer 3

found the incidence to be 62% in 1000 school

children aged 14 years. This trend toward an in-

creased incidence of mandibular incisor crowding

with age in untreated persons has been reported by

607

608 Bishara, Khadivi, and Jakobsen American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacia( Orthopedics

December 1995

others. .1 Sinclair and Little 6 quantified the dis-

pl acement in t he mandi bul ar incisor contact points

and found it significantly increase from 9 to 29

years. Fost er et al. 7 report ed a peak at 14 years;

Sinclair, 5 Moorrees, ~ and Bi shara et al. 9 report ed a

cont i nued increase into young adulthood. Bi shara

et al. ~ observed an additional increase bet ween 25

and 45 years of age in bot h mal e and femal e

subjects. They observed t hat t oot h size-arch length

discrepancy from early adol escence (13 years of

age) to mi d-adul t hood (45 years of age) increased

significantly in bot h the maxillary and mandi bul ar

arches. The increases were calculated to be 1.9 mm

in mal e subjects and 2.0 mm in femal e subjects in

the maxillary arch, whereas the correspondi ng

changes were 2.7 and 3.5 mm in the mandi bul ar

arch.

Sinclair 5 observed t hat incisor crowding in nor-

mal unt reat ed per sons occurs at a rat e t hat is about

one third t hat of t reat ed persons. The changes in

the latter group were consistent despite widely

varying initial and final crowding indices. This

seems to indicate t hat t he changes are i ndependent

of the initial malocclusion or t he "success" of the

t r eat ment rendered.

Vari ous investigators at t empt ed to det ermi ne

the relationship bet ween crowding and ot her

dentofacial paramet ers. Moorrees et al. 1~ suggested

that a decrease of the incisor-canine ci rcumference

not ed from 13 to 18 years of age was associated

with a decrease in arch length rat her t han a nar-

rowing in arch width. Similar observations were

made by DeKock 12 who quantified the average

reduct i on to be 10%. Car men ~3 found no significant

rel at i onshi p bet ween incisor crowding, gender, and

Angl e classification. Changes in arch length and

i nt ercani ne and mol ar widths may partly cont ri but e

to a multifactorial relationship that is associated

with crowding. 9

Al t hough several investigators 4'~42 suggested

t hat t he amount and direction of facial growth may

be partially responsible for t he changes in the

mandi bul ar incisor position, ot hers 6'9 did not find

significant associations bet ween the skeletal rela-

tionships and dental changes.

Sanin and Savara 21 found a correl at i on bet ween

mandi bul ar incisor crowding and the size of the

first molars, as well as the angle formed by the long

axis of the mandi bul ar incisors and molars. They

devel oped a probability table t hat was used to

predi ct t he incisor crowding at age 14 years from

variables measured at age 8 years, with a 15%

est i mat e of error. On the ot her hand, Howe et al., z2

as well as Sinclair and Little, 6 found no clinically

significant associations bet ween various mandi bul ar

par amet er s and incisor crowding, and they con-

cluded that no predictive equat i on can accurately

forecast t he nat ure and extent of the changes in

lower incisor crowding.

The literature review indicates that clinicians

and researchers are i nt erest ed in predicting the po-

tential for a t oot h size-arch length discrepancy in

their growing patients. If accurat e predictions can be

made while the pat i ent is in t he deciduous dentition,

clinicians might want to explore the feasibility of

various approaches to i nt ercept these developing

malocclusions. On the ot her hand, if such discrepan-

cies cannot be accurately predi ct ed one will have to

question the advisability of such procedures.

The purpose of this study is to det ermi ne the

changes in the maxillary and mandi bul ar t oot h

size-arch length discrepancies (TSALD) at the time

of t he compl et e erupt i on of the deciduous denti-

tion (X age -- 4.0 years) to t he time of eruption of

t he second mol ars (X age = 13.3 years). In addi-

tion, an at t empt was made to det ermi ne whet her

TSALD in the early per manent dentition can be

predi ct ed from various par amet er s measured at t he

deciduous dentition stage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Records of 35 male and 27 female subjects who were

participants in the Iowa Longitudinal Growth Study were

evaluated. 23'24 Each subject had a normal occlusion at the

time of eruption of the deciduous teeth, no apparent

facial disharmony, none had congenitally missing teeth or

had undergone orthodontic therapy throughout the pe-

riod of study. Normal occlusion was defined as having a

flush terminal plane or a mesial step between the distal

surfaces of the opposing second deciduous molars, 0% to

50% overbite and 0 to 3 mm of ovejet.

Each subject had complete dental casts at two stages

of dental development, namely, at the time of complete

eruption of the deciduous dentition and at the time of

eruption of the permanent second molars. These selec-

tion criteria limited the number of subjects in this inves-

tigation to 62, 35 males and 27 females.

Parameters measured

A. Arch length: The mesiodistal length of the fol-

lowing arch segments were measured in the max-

illary and mandibular arches for the right and left

sides; ~'2S (1) Anterior segments, between the me-

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Bishara, Khadivi, and Jakobsen 609

Volume 108, No. 6

sial contact points of the central incisors and the

points between the lateral incisors and canines,

(2) posterior segments, between the contact

points of the lateral incisors and canines and the

distal of the second deciduous molars or the

mesial of the first permanent molars. The total

arch lengths was also calculated.

B. Tooth size measurements: The mesiodistal widths

of the maxillary and mandibular deciduous and

succedaneous teeth were measured. These mea-

surements were obtained from casts in which the

dentitions were complete and in good condition.

Crown diameters were taken as the distance be-

tween the anatomic contact points. 26'27

C. Tooth size-arch length discrepancy (TSALD):

Two types of TSALD were calculated, total

TSALD mesial to the second deciduous molars or

permanent first molars, and anterior TSALD be-

tween the two canines. The TSALD was calcu-

lated for both the maxillary and mandibular

arches by subtracting the sum of the mesiodistal

diameter of the appropriate teeth from the avail-

able arch length.

Approximately 68 different variables were either

measured or calculated from the various measurements.

All measurements were performed by two investiga-

tors working independently. Each investigator performed

each measurement twice on different occasions. Intrain-

vestigator and interinvestigator discrepancies were pre-

determined at 0.25 ram.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, including the mean, standard

deviation, minimum and maximum values, were calcu-

lated for the various measurements.

Student t tests were used to determine whether

significant differences were present between the right

and left sides for both the male and female subjects.

Correlation coefficients "r" were performed between the

deciduous and corresponding permanent teeth and also

for the arch length and width parameters, as well as

tooth size-arch length relationships in the two dentitions.

Significance was predetermined at the 0.05 level of con-

fidence.

Stepwise regression analysis (R 2) was used to deter-

mine which of the variables could be included in a

regression model, i.e., to determine associations between

maxillary and mandibular TSALD arches in the perma-

nent dentition. This procedure is useful in isolating a

subset of predictor variables that best explain the varia-

tion of the dependent variableY

Discriminant analysis was used to supplement the

findings from the regression analysis since it provides a

mean of assessing the predictive accur acy- t hat is, the

percentage of cases correctly classified by the prediction

equation. 29

RESULTS

Right - left side comparisons: The results of t he

St udent t tests i ndi cat ed t hat t he mesi odi st al di am-

et ers of t he ant i meres, as well as ant eri or and

post eri or arch lengths, wer e not significantly differ-

ent bet ween t he right and left sides. Thi s was t rue

for bot h t he maxillary and mandi bul ar arches.

Male -female comparisons: St udent t tests indi-

cat ed t hat mal e subjects wer e l arger t han f emal e

subjects in a number of dent al arch par amet er s, as

well as in t he mesi odi st al crown di amet ers. As a

result, t he findings for mal e and femal e subjects are

pr esent ed separat el y.

Correlations (r) between the mesiodistal diameter

of the deciduous and succedaneous teeth (Table I):

Wi t h t he except i on of t he maxillary second molars,

all deci duous t eet h were significantly cor r el at ed t o

t hei r per manent successors. All t he correl at i ons

wer e l ower t han 0.7 with t he except i on of t he

f emal e correl at i ons bet ween t he maxillary cent ral

incisors (r = 0.81 and 0.78) and t he mandi bul ar

cent ral (r = 0.78 and 0.76) and lateral (r = 0.76

and 0.70) incisors.

Correlations (r) between the deciduous and per-

manent arch length segments (Table II): All arch

segment s wer e significantly cor r el at ed in t he de-

ci duous and per manent dent i t i ons except for t he

mandi bul ar ri ght and left ant eri or segment s. All

t he significant correl at i ons were bel ow 0.7 except

for t he maxillary post eri or segment s (r = 0.73 and

0.79) in mal e subjects.

Correlations between total tooth size-arch length

discrepancies (TSALD) in the deciduous and perma-

nent dentitions (Table III). All correl at i ons were

significant but bel ow 0.7.

Multiple Regression Analysis: The previ ousl y

ment i oned findings i ndi cat ed t hat in general , t her e

wer e significant correl at i ons (r) in t oot h size, arch

length, and TSALD bet ween t he deci duous and

per manent dent i t i ons. The maj ori t y of t hese corre-

lations wer e bel ow 0.7. As a result, mul t i pl e regres-

sion analysis (R 2) was used to det er mi ne whet her

t he addi t i on of ot her vari abl es can i mprove t he

ability t o predi ct t he TSALD in t he per manent

dent i t i on. The results of t he Mul t i pl e Regr essi on

Anal ysi s (Tabl e IV) i ndi cat ed t hat t he scores for R 2

r anged bet ween a low of 0.1737 for Tot al Mandi bu-

lar TSALD in femal e subjects t o a high of 0.7474

for Tot al Maxillary TSALD in mal e subjects. The

Di scri mi nant Anal ysi s (Tabl e IV) was used to de-

t er mi ne how accurat el y t hese predi ct i on equat i ons

610 Bishara, Khadi vi , and Jakobsen American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics

December 1995

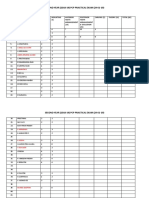

Table I. Correlation coefficients (r) bet ween the mesiodistal tooth size of the deciduous and succedaneous

permanent t eet h

Maxillary

D1 D2

T4 T5

Mal es 0.33 0. 41' *

Femal es 0.11 0.60**

D3

T6

D4 D5

T7 T8

D6

T9

D7

TIO

D8

Tl l

D9 DIO

T12 T12

0.11 0.44** 0.45** 0.65** 0.49** 0.45** 0.53* 0.22

0.57** 0.45** 0.78** 0.81"* 0.54** 0.73** 0.75** 0.41"

*p _< 0.05; **p -< 0.01.

D1-DIO, maxillary deci duous t eet h from right to left.

T4-T12, maxillary per manent succesdaneous t eet h from right to left.

Dl l -D20, mandi bul ar deci duous t eet h from left to right.

T20-T29, mandi bul ar per manent succedaneous t eet h from left to right.

Tabl e II. Correlation coefficients (r) bet ween the

deciduous and per manent arch

length segments

R Post R Ant L Ant L Post

Maxillary

Mal es 0.73** 0.63** 0.66** 0.79**

Femal es 0.49** 0.60** 0.39* 0.52**

Mandi bul ar

Mal es 0.56** 0.22 0.21 0.54**

Femal es 0.62** 0.47** 0.53** 0.59**

L = Left; R = right; Ant = anterior; Post = posterior; *p _<

0.05; **p -< 0.01.

can correctly classify the expect ed TSALD in the

permanent dentition for each person. The results

of the Discriminant Analysis for correctly classify-

ing individual subjects ranged bet ween a low of

40.8% to a high of 77.8%.

DI SCUSSI ON

One of the ultimate goals of attempting to

quantify the changes in t oot h size-arch length dis-

crepancy bet ween the deciduous and per manent

dentitions is prediction. The results of the correla-

tion coefficients (r), indicate that t here are a num-

ber of significant correlations bet ween the various

variables in the deciduous and permanent denti-

tions, but these correlations were relatively low

( <0. 7) with the exception of the incisors in fe-

males. The Multiple Regression Analysis (R 2) did

not significantly improve the predictive abilities. In

addition, the Discriminant Analysis indicated that

the percent age of cases correctly classified by the

prediction equations were, in general, relatively

low.

Horowi t z and Hixon 3 have stated that correla-

Table I I I . Correlations coefficients (r) bet ween

total t oot h size and arch length

discrepancies in the deciduous and

permanent dentitions

Males Females

Maxillary 0.47"* 0.69"*

Mandi bul ar 0.46"* 0.48"*

**p _< 0.01.

tion coefficients of less t han r = 0.7 or r = 0.8 have

little predictive value when applied to a person. A

correlation coefficient of r = 0.7 means that less

than half of the total variation can be eliminated in

prediction. When the guidelines of Horowitz and

Hixon 3 were applied to the present data, few of

the correlations were sufficiently high to be useful

for prediction. Furt hermore, the results did not

follow a detectable pat t ern bet ween male and fe-

male subjects, bet ween the maxillary and mandibu-

lar arches, as well as bet ween the total and anterior

TSALD.

In previous studies, 213 increases in the TSALD

bet ween early adolescence and early adulthood

have been consistently observed. These changes

were primarily the result of a decrease in the

available arch length bot h anteriorly and posteri-

orly. 2-13 The changes in maxillary and mandibular

TSALD in the per manent dentition were not found

to have a strong association with ot her dental arch

variables in the deciduous dentition. 6'9

The present findings and that of others 31-33 have

poi nt ed to the difficulty of predicting the eventual

TSALD in the per manent dentition from dental

arch measurement s in the deciduous dentition. On

the ot her hand, predicting TSALD in the mixed

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Bi shara, Khadi vi , and Jakobs en 611

Volume 108, No. 6

Mandibular

Dl l

T20

D12

T21

D13 D14

T22 T23

D15

T24

D16

T25

0.51"* 0.36* 0.43** 0.50** 0.56** 0.51"*

0.53** 0.58** 0.46** 0.76** 0.78** 0.76**

D17 D18

T26 T27

0.45** 0.38*

0.70** 0.49**

D19 D20

T28 T29

0.46** 0.52**

0.44* 0.42*

Table IV. Results of the stepwise regression analysis indicating the various significnat variables that

contribute to R 2 with TSALD of various arch segments as the independent variable

Variable Portal R 2 Variable Portal R 2

Mal es R 2 = 0.7474

Di fference bet ween t he size of t he maxillary

deci duous and per manent t eet h

Maxillary total arch l engt h

Sum of maxillary deci duous t eet h

Change in mandi bul ar mol ar wi dt h

Di scri mi nant analysis

Mal es R 2 = 0.5532

Mandi bul ar deci duous t eet h

Sum of mandi bul ar deci duous per manent t eet h

Tot al mandi bul ar arch l engt h

Change in mandi bul ar mol ar width

Di scri mi uant analysis =

Mal es R 2 = 0.3238

Maxillary deci duous arch l engt h

Sum of maxillary deci duous t oot h size

Di fference in size of maxillary deci duous and

per manent t eet h

Di scri mi nant analysis =

Mal es R 2 = 0.5608

Mandi bul ar deci duous t oot h size

Di fference bet ween mandi bul ar deci duous and

per manent t oot h size

Mandi bul ar deci duous arch l engt h

Mandi bul ar i nt ermol ar width

Di scri mi nant analysis =

Total maxillary TSALD

Femal es R z = 0.1245

0.1325 Mandi bul ar i nt ercani ne width

0.1627

0.4030

0.0493

68.5%

Total mandi bu&r TSALD

0.1020

Femal es R e = 0.1737

Vari at i ons bet ween t he di fferences in maxillary

and mandi bul ar t oot h size from t he deci duous

to t he per manent dentitions

0.1229

0.2286

0.0996

69.0%

Anterior maxillary TSALD

Femal es R 2 = 0.7267

0.1200 Change in mandi bul ar i nt ercani ne width

0.0803 Change in maxillary i nt ercani ne wi dt h

0.1235 Maxillary deci duous t oot h size

0.1245

50.8%

0.1737

40.8%

0.2456

0.1470

0.0972

Mandi bul ar deci duous arch l engt h 0.1362

Di fference bet ween maxillary and mandi bul ar 0.0604

t oot h size

Maxillary deci duous arch l engt h 0.0403

59.1% 77.8%

Anterior mandibular TSALD

Femal es R 2 = 0.4003

0.2485 Change in mandi bul ar mol ar width 0.1266

0.1143 Change in maxillary cani ne width 0.2738

0.0946

0.1034

77.3% 51.9%

dentition can be performed with much greater

accuracy. 34 This is because the dental arch dimen-

sions, particularly in the mandible, are established

by the time the mandibular incisors have erupted.

Added to that is the fact that a number of accurate

prediction equations have been developed that can

accurately estimate the mesiodistal diameters of

the unerupted premolars and canines. 35-36

612 Bishara, Khadivi, and Jakobsen American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics

December 1995

Ther ef or e clinicians who are i nt erest ed in earl y

t r eat ment shoul d base t hei r di agnost i c decisions on

t oot h si ze-arch l engt h analyses per f or med in t he

mi xed dent i t i on and not in t he deci duous dent i t i on.

Accur at e est i mat es of space di screpanci es will in

t urn allow t he clinician t o deci de whet her t he

pat i ent woul d benefi t f r om a gui dance of erupt i on

pr ocedur e or serial ext ract i ons i ncl udi ng t he re-

moval of first premol ars.

The pr esent and previ ous findings 5'1'13 indi-

cat ed t hat t he changes in t he dent ofaci al st ruct ures

are compl ex and t hat t he processes t hat i nt erpl ay t o

i nfl uence t he rel at i onshi p among t he teeth, t he

dent al arches, and t he face, al t hough identifiable,

are not yet compl et el y under st ood or predi ct abl e.

Ther ef or e bot h clinicians and par ent s need t o

accept t he fact t hat for t he present time, it is

difficult duri ng t he deci duous dent i t i on stage to

predi ct t he magni t ude of t he fut ure TSALD. Earl y

mechani cal i nt ervent i on in t he deci duous dent i t i on

of a phe nome non t hat cannot be accurat el y diag-

nosed or predi ct ed in a part i cul ar per son is t here-

fore not r ecommended. This deci si on has t o be

post poned until t he mi xed dent i t i on aft er t he erup-

t i on of t he per manent incisors.

It has also been suggest ed t hat post r et ent i on

changes in t oot h si ze-arch l engt h rel at i onshi p are,

at least in part , rel at ed t o t he "nor mal " devel op-

ment al changes and shoul d be expect ed in most

persons whet her or not t hey have under gone ort h-

odont i c t r eat ment . The pat i ent , and t he par ent s of

persons seeki ng or t hodont i c t r eat ment , shoul d be

made aware of this phenomenon.

Accor di ng t o Hor owi t z and Hixon37:

The significant point is that orthodontic therapy may

temporarily alter the course of these physiologic changes

and possibilities, for a time, even reverse them; however,

following mechanics-therapy and the period of retention-

restraint the developmental maturation process resumes.

It needs t o be r emember ed t hat t he changes in

arch di mensi ons as well as t oot h posi t i on and

i ncl i nat i on are, in part , compensat or y mechani sms

t hat serve t o mai nt ai n t he bal ance among t he

vari ous funct i onal and st ruct ural demands pl aced

on t he face and dent i t i on. Many of t hese changes

are difficult t o predi ct in t he deci duous dent i t i on

stage.

CONCLUSI ONS

Al t hough it is of t en suggest ed t hat post t reat -

ment and post r et ent i on mandi bul ar incisor crowd-

ing are rel at ed t o i nadequat e or t hodont i c diagnosis

and t r eat ment pl anni ng, this investigation i ndi cat es

t hat addi t i onal fact ors are involved and shoul d be

consi der ed in explaining this phenomenon. These

fact ors are pr esent in most per sons whet her or not

t hey have a mal occl usi on or have under gone ort h-

odont i c t reat ment .

The changes in t he al i gnment of t he t eet h are

pri mari l y t he result of a decr ease in t he available

arch l engt h in bot h t he maxillary and mandi bul ar

arches. The Regr essi on Anal ysi s i ndi cat es t hat t hese

changes are rel at ed in part , t o t oot h size as well as t o

arch l engt h and arch wi dt h changes. The correl a-

tions bet ween t he vari ous deci duous and per manent

TSALD are of such a magni t ude t hat does not allow

an accurat e predi ct i on of di screpanci es in t he per-

manent dent i t i on f r om t he available dent al mea-

surement s in t he deci duous dent i t i on.

REFERENCES

1. Van der Linden FPGM. Theoretical and practical aspects of

crowding in the human dentition. J Am Dent Assoc 1974;

89:139-53.

2. Barrow GV, White JR. Developmental changes of the max-

illary and mandibular dental arches. Angle Orthod 1952;22:

41-6.

3. Cryer S. Lower arch changes during the early teens. Trans

Eur Orthod Soc 1965;41:87.

4. Lundstr6m A. Changes in crowding and spacing of the teeth

with age. Dent Pract 1968;19:218-24.

5. Sinclair PM. A longitudinal evaluation of the dental and

skeletal changes in untreated normals from the mixed den-

tition into adulthood [Master's thesis]. Seattle: University of

Washington, 1981.

6. Sinclair PM, Little RM. Maturation of untreated normal

occlusions. AM J ORTHOD 1983;83:114-23.

7. Foster TD, Hamilton MC, Lavelle CLB. A study of dental

arch crowding in four age groups. Dent Pract 1970;21:9-12.

8. Moorrees CFA. The dentition of the growing child. Cam-

bridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1959.

9. Bishara SE, Jakobsen JR, Treder JE, Stasi MJ. Changes in

the maxillary and mandibular tooth size-arch length rela-

tionship from early adolescence to early adulthood. AM J

ORTHOD DENTOFAC ORTHOP 1989;95:46-59.

10. Bishara SE, Treder JE, Jakobsen JR. Facial and dental

changes in adulthood. AM J ORTHOD DENTOFAC ORTHOP

1994 tin press].

11. Moorrees CFA, Lebret LML, Kent RL. Changes in the

natural dentition after second molar emergence (13-18

years). IADR abstracts 1979:276.

12. DeKock WH. Dental arch depth and width studied longi-

tudinally from 12 years of age to adulthood. AM J ORTHOD

1972;62:56-66.

13. Carmen RB. A study of mandibular anterior crowding in

untreated cases and its predictability [Master's thesis].

Cleveland, Ohio: Case Western Reserve University, 1978.

14. Bj6rk A. Skieller V. Facial development and tooth eruption.

An implant study at the age of puberty. AM J ORTHOD

1972;62:339-83.

15. Hunter WS. The dynamics of mandibular arch perimeter

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Bishara, Khadivi, and Jakobsen 613

Volume 108, No. 6

changes from mixed to permanent dentitions. In: Mc-

Namara JA Jr, ed. The biology of occlusal development.

Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1977.

16. Hunt er WS, Smith BRW. Development of mandibular spac-

ing-crowding from 9-16 years of age. J Can Dent Assoc

1972;38:178-85.

17. Isaacson R, Zapfel R, Worms F, Erdman A. Effects of

rotational jaw growth on the occlusion and profile. AM J

ORTHOD 1977;72:276-86.

18. Lavergne J, Gasson N. The influence of jaw rotation on the

morphogenesis of malocclusion. AM J ORTHOD 1978;73:

658-66.

19. Leighton BD, Hunter WS. Relationship between lower arch

spacing/crowding and facial height and depth. AM J

ORTEIOD 1982:658-66.

20. Lundst rfm A. A study of the correlation between mandibu-

lar growth direction and changes in incisor inclination,

overjet, overbite and crowding. Trans Eur Orthod Soc

1975:131-40.

21. Sanin C, Savara BC. Factors that affect the alignment of the

mandibular incisors. A longitudinal study. AM J ORTHOD

1973;64:248-57.

22. Howe RP, McNamara JA Jr, O'Connoi- KA. An examination

of dental crowding and its relationship to tooth size and

arch dimension. AM J ORTHOD 1983;83:363-73.

23. Meredith HB. A longitudinal study of growth in face depth

during childhood. Am J Phys Anthropol 1959;17:125-35.

24. Meredith HV, Hopp WN. A longitudinal study of dental

arch width of the deciduous second molctrs in children 4-8

years of age. J Dent Res 1956;35:879-89,

25. Sillman JH. Dimensional changes of the dental arches:

longitudinal study from birth to 25 years. AM J ORTHOD

1964;50:824-41.

26. Fuller JL, Denehy GE. Concise dental anatomy and mor-

phology; a self-paced text. Chicago: Year Book Medical

Publishers, 1979.

27. Hunter WS, Priest WR. Errors and discrepancy in measure-

ment of tooth size. J Dent Res 1960;39:405-14.

28. SAS user' s guide. Raleigh, North Carolina: 1979:391.

29. SPSS user' s guide. Chicago: 1983:623.

30. Horowitz SL, Hixon EH. The nature of orthodontic diagno-

sis. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1966.

31. Clinch LM. A longitudinal study of the mesio-distal crown

diameters of the deciduous teeth and their permanent

successors. Trans Eur Orthod Soc 1963:202-15.

32. Leighton CB. The early signs of malocclusion. Trans Eur

Orthod Soc 1969:353-68.

33. Solow B. The association between the spacing of the incisors

in the temporary and permanent dentitions in the same

individuals. Trans Eur Orthod Soc 1958:287-300.

34. Bishara SE, Staley RN. Mixed-dentition mandibular arch

length analysis: a step-by-step approach using the revised

Hixon-Oldfather prediction method. AM J ORTHOD 1984;

86:130-5.

35. Staley RN, Kerber PE. A revision of the Hixon and Old-

fathr mixed dentition prediction method. AM J ORTHOD

1980;78:296-302.

36. Staley RN, O' Garman TW, Hoog JE Shelly TH, Prediction

of the widths of unerupted canines and premolars. J Am

Dent Assoc 1984;108:185-90.

37. Horowitz S, Hixon E. Physiologic recovery following orth-

odontic treatment. AM J ORTHOD 1969;55:1-4.

Reprint requests to:

Dr. Samir E. Bishara

Department of Orthodontics

College of Dentistry

University of Iowa

Iowa City, IA 52342

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Orthodontic Treatment Planning: Problem List To Specific PlanDocument49 paginiOrthodontic Treatment Planning: Problem List To Specific PlanYusra AqeelÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1000 MCQDocument157 pagini1000 MCQSaeed KayedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ortho I Study QuestionsDocument7 paginiOrtho I Study QuestionsbenjamingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Age EstimationDocument8 paginiAge EstimationNoÎncă nu există evaluări

- MBT 2Document11 paginiMBT 2NaveenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Band and Loop Space MaintainerDocument4 paginiBand and Loop Space MaintainerdrkameshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Klasifikasi AramanyDocument7 paginiKlasifikasi AramanyThio ZhuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Of Dental Sciences: Case ReportDocument4 paginiOf Dental Sciences: Case ReportGede AnjasmaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class III High Angle Malocclusion Treated With Orthodontic Camouflage (MEAW Therapy)Document24 paginiClass III High Angle Malocclusion Treated With Orthodontic Camouflage (MEAW Therapy)Beatriz ChilenoÎncă nu există evaluări

- First Internal PCP PracticalDocument4 paginiFirst Internal PCP PracticalSatya AsatyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Differences Between Primary Teeth (Milk Teeth) and Permanent TeethDocument4 paginiDifferences Between Primary Teeth (Milk Teeth) and Permanent TeethRizkia Retno DwiningrumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Upper Midline CorrectionDocument5 paginiUpper Midline CorrectionmutansÎncă nu există evaluări

- Occlusion 7Document10 paginiOcclusion 7krondanÎncă nu există evaluări

- DMF 40 199 PDFDocument14 paginiDMF 40 199 PDFsiraj_khan_13Încă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of C-Shaped Canals by Panoramic Radiography and Cone-Beam Computed Tomography - Root-Type Specificity by Longitudinal DistributionDocument5 paginiAnalysis of C-Shaped Canals by Panoramic Radiography and Cone-Beam Computed Tomography - Root-Type Specificity by Longitudinal DistributionAnthony LiÎncă nu există evaluări

- TaurodontDocument14 paginiTaurodontHameed WaseemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lever Arm. Angle Orthodontics. 2008Document9 paginiLever Arm. Angle Orthodontics. 2008Mir EspadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CementumDocument18 paginiCementumBahia A RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rugoscopy 1Document7 paginiRugoscopy 1shrutiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test - 8 Retension, Dystopia, PericoronitisDocument5 paginiTest - 8 Retension, Dystopia, PericoronitisIsak ShatikaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Differential Diagnosis of Skeletal Class IIIDocument8 paginiDifferential Diagnosis of Skeletal Class IIIsolodont1Încă nu există evaluări

- Ortho Pedo Traumatic InjuriesDocument4 paginiOrtho Pedo Traumatic InjurieschloieramosÎncă nu există evaluări

- 001 - 09 Q - A - DR Michael Melkers - Occlusion in Everyday PracticeDocument14 pagini001 - 09 Q - A - DR Michael Melkers - Occlusion in Everyday PracticeMinh ThongÎncă nu există evaluări

- J Cos Lot QuadratoDocument10 paginiJ Cos Lot QuadratoMARLON ADOLFO CESPEDES ALCCAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ijcrims 1Document9 paginiIjcrims 1smritiÎncă nu există evaluări

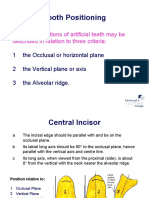

- Tooth Positioning: The Basic Positions of Artificial Teeth May Be Described in Relation To Three CriteriaDocument19 paginiTooth Positioning: The Basic Positions of Artificial Teeth May Be Described in Relation To Three CriteriaCherine SnookÎncă nu există evaluări

- 03 01 ARTICOL Classification System For The Completely Dentate PatientDocument10 pagini03 01 ARTICOL Classification System For The Completely Dentate PatientRalu BugzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rests: Rest SeatsDocument43 paginiRests: Rest Seatsreem eltyebÎncă nu există evaluări

- Incisor Crown Shape and CrowdingDocument6 paginiIncisor Crown Shape and CrowdingAndrésAcostaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diagnostic Aids in Orthodontics Full 1Document54 paginiDiagnostic Aids in Orthodontics Full 1Parijat Chakraborty PJÎncă nu există evaluări