Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Chirurgie

Încărcat de

Anca GuraliucDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Chirurgie

Încărcat de

Anca GuraliucDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Vijeev Vasudevan et al

250

JAYPEE

CASE REPORT

Well-differentiated Squamous Cell Carcinoma of

Maxillary Sinus

Vijeev Vasudevan, S Kailasam, MB Radhika, Manjunath Venkatappa, Devaraju Devaiah, TG Shrihari, M Sudhakara

ABSTRACT

Paranasal sinus malignancies are exceedingly rare. Chronic

respiratory tract infections, nasal congestive symptoms and

rhinosinusitis are much more prevalent in recent days and

manifest many symptoms that overlap with those of sinus

malignancy. Symptoms may be nonspecific and indolent for

months or even years, leading to delay in diagnosis and

consequent advanced diseased stage at presentation. The

majority of maxillary sinus tumors in the literature have presented

with advanced stage, resulting in generally poor survival

outcomes. Hence, it is imperative that maxillofacial stomatologist

should be aware of sinus pathologies, to diagnose early and it

should alert them to include in differential diagnosis.

Keywords: Squamous cell carcinoma, Maxillary sinus, X-ray

tomography, Diagnosis.

How t o ci t e t hi s ar t i cl e: Vasudevan V, Kailasam S,

Radhika MB, Venkatappa M, Devaiah D, Shrihari TG,

Sudhakara M. Well-differentiated Squamous Cell Carcinoma

of Maxillary Sinus. J Indian Aca Oral Med Radiol 2012;24(3):

250-254.

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None declared

INTRODUCTION

Maxillary sinus cancer is relatively rare neoplasm with an

incidence representing a small percentage (0.2%) of human

malignant tumors and only 1.5% of all head and neck

malignant neoplasms.

1

Because of the relative rarity of

carcinoma of the maxillary sinus, institutional experience

is usually limited. The incidence seems to vary in different

parts of the world, with Asian countries reporting high

numbers of cases.

2

Maxillary sinus cancer is very difficult

to treat and traditionally have been associated with a poor

prognosis. One reason for these poor outcomes is the close

anatomic proximity of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses

to vital structures, such as the skull base, brain, orbit and

carotid artery. This complex location makes complete

surgical resection a challenging and sometimes impossible

task. In addition, these tumors tend to be asymptomatic at

early stages, appearing more frequently at late stages once

extensive local invasion has occurred.

CASE REPORT

A healthy 50-year-old man was referred to our oral medicine

department with the chief complaint of pain and swelling

of the left maxillary quadrant with nasal discharge. The

10.5005/jp-journals-10011-1307

patient had just completed a 5 days course of antibiotics

and analgesics for a presumed infection of odontogenic

origin with minimal improvement in his symptoms. His

medical history revealed a 3 pack/day, cigarette/beedies

smoking habit since childhood. He also had a habit of using

nasal snuff. Patient is on treatment for cough and chest pain

since 5 years. Patient gave a history of tooth removal for

mobility 5 days back in same quadrant and ulcer in relation

to same post-treatment.

Clinical examination showed a moderately firm soft

tissue swelling in the area of the left maxillary region; its

maximum dimension measured 2 cm (Fig. 1A). The lesion

was mildly painful to palpation. Lymph node blocks on the

neck did not have any positive sign.

On further questioning, the patient reported slight

paresthesia involving the distribution of the left posterior

superior alveolar nerves. Ulceroproliferative growth

measuring around 4 4 cm in maximum diameter was noted

in relation to 25, 26, 28 region, some purulent drainage was

obtained from the unhealed extraction socket in relation to

26, 27 (Fig. 1B). Generalized attrition, cervical abrasion

and mobility were noted.

A preliminary panoramic radiograph revealed missing

26, 27 and 16 and few decayed teeth and generalized

moderate to severe periodontal bone loss. A poorly defined

opacification was noted in the area of the left maxillary

sinus. The floor, roof and posterior and medial walls of the

left maxillary sinus appeared to be destroyed (Fig. 2).

Waters view showed that the opacification of the left

maxillary sinus has expanded to involve the entire left

maxillary sinus. Intraoral extension of this mass was also

evident. The inferior, posterior, lateral and medial walls of

the left maxillary sinus and the left orbital floor appear to

be destroyed completely (Fig. 3).

The patient was referred to the radiology department of

a local hospital, where plain computed tomography (CT)

was performed. The scan revealed significant destruction

of the anterior, posterior, medial and lateral walls of the

maxillary sinus as well as of the left orbital floor. Features

were of carcinoma of left maxillary antrum with invasion

in to the left orbit, ethmoid air cells, hard palate, nasal cavity

and infratemporal fossa (Figs 4A and B).

In view of paresthesia and growth in the area of

complaint, a biopsy of the involved areas was deemed

Journal of Indian Academy of Oral Medicine and Radiology, July-September 2012;24(3):250-254

251

Well-differentiated Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Maxillary Sinus

JIAOMR

Fig. 1A: Extraoral photograph taken clinically. Substantial

expansion is apparent over the area of the left maxillary sinus

Fig. 1B: A sizable intraoral mass is evident in the area of the left

maxillary buccal sulcus. Extending palatally involving alveolar ridge

Fig. 2: Panoramic radiograph reveals a poorly defined opacification

located in the area of the left maxillary sinus. The inferior, posterior

and medial walls of the left maxillary sinus and the left orbital floor

all appear to be destroyed

necessary to rule out the possibility of an underlying

malignant process. Surgical exploration of the area revealed

an irregular 1 1 cm bony defect filled with granulation-

like tissue on the posterior-lateral wall of the left maxillary

sinus. This soft tissue was submitted for histopathological

examination.

Microscopic examination of the biopsy specimen

revealed pseudostratified epithelial cells with signs of

dysplasia. Invading the deeper connective tissue in the form

of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, showing

numerous keratin pearls (Figs 5A and B).

A diagnosis of well-differentiated squamous cell

carcinoma was reached. The patient was referred to the head

and neck surgery department for further treatment and

explained about the surgery, chemotherapy and

brachytherapy. Patient declined of treatment due to poor

socioeconomic background. Patient was advised on for

palliative therapy. Later, the patient succumbed within an

8 months time.

DISCUSSION

Maxillary sinus carcinoma presents a diagnostic and

therapeutic challenge to the oral diagnostician, surgeon and

as well as the radiation oncologist. The early symptoms are

generally vague and consistent with benign disorders. When

the tumors are small sized, they are misdiagnosed as chronic

sinusitis, nasal polyp, lacrimal duct obstruction or even

cranial arteritis.

3

In general, clinical examination of patients presenting

with pain and swelling of the jaws will reveal lesions of

dental etiology, most commonly related to pulpal or

periodontal pathology. However, when such situation exists,

it is mandate that dental practitioner must consider the

possibility of a nonodontogenic etiology. It is often better

to determine first, by clinical and radiographic examination,

whether the enlargement originates primarily in bone or in

the extraosseous soft tissue. An infection of odontogenic

origin is the most common cause of a soft tissue swelling of

the maxillary buccal vestibule. Second, the possibility of a

malignant neoplasm of the maxillary antrum, although

uncommon, should be considered.

In the present patients case, extensive dental decay and

periodontal disease (mobility of 26, 27), it would have

initially felt that this swelling was most likely the result of

an acute dental abscess secondary to pulpal involvement.

The previous dentist has extracted the teeth. The associated

soft tissue swelling was the result of tumor expansion

through a defect in the posterolateral wall of the left

maxillary sinus. In 40 to 60% of cases, there are facial

asymmetry, oral cavity swelling and tumor extension to the

nasal cavity. These lesions extend medially toward the nasal

cavity; superiorly they may invade the orbit and ethmoid

sinus; anterolaterally, they may reach soft tissues and cheek,

and inferiorly, the maxillary sinus floor, dental alveolus and

Vijeev Vasudevan et al

252

JAYPEE

Fig. 4A: Axial view CT with soft tissues window. Heterogeneous,

expansive lesion, with infiltrative aspect, centered on the left

maxillary sinus

Fig. 4B: Coronal view CT with osseous window. Expansive

lesion of left maxillary sinus with medial and anterolateral walls

erosion

Fig. 5A: Low power photomicrograph (10) showing antral

wall lining. The epithelial cells are pseudo stratified with signs of

dysplasia

Fig. 5B: Low power photomicrograph (10) showing dysplastic

epithelium invading the deeper connective tissue in the form of

well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma showing numerous

keratin pearls

Fig. 3: Waters view shows the opacification of the left maxillary

sinus has expanded to involve the entire left maxillary sinus. Intraoral

extension of this mass is also evident. The inferior, posterior, lateral

and medial walls of the left maxillary

palate. Posteriorly, they may reach the pterygopalatine fossa

and pterygoid muscles. Through the pterygoid fossa, they

may superiorly extend toward the orbital fissure and the

cavernous sinus.

4

Symptoms that are commonly noted with involvement

of the sinonasal complex include maxillary swelling,

epistaxsis, nasal obstruction or discharge, diplopia and

proptosis. When these classic signs are not present, the

possibility of a malignant tumor may be overlooked.

5,6

In the given case, patient had maxillary swelling, nasal

discharge and paresthesia of the involved nerve. Signs that

should alert the clinician to the possibility of a malignant

tumor include paresthesia, radiographic evidence of

irregular bone resorption and localized irregular widening

of the periodontal ligament. Among these, paresthesia is an

ominous sign. Although paresthesia can be related to nerve

Journal of Indian Academy of Oral Medicine and Radiology, July-September 2012;24(3):250-254

253

Well-differentiated Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Maxillary Sinus

JIAOMR

damage secondary to previous surgical procedures,

metabolic disorders or infection, it is mandatory that the

possibility of a malignant neoplasm be ruled out in all

patients presenting with paresthesia.

7,8

In the present case, the clinical examination of lymph

nodes was not palpable for any positive sign toward

malignancy. This low incidence may be associated with the

poor lymphatic draining of the maxillary sinus or with the

clinical inaccessibility for the affected lymph nodes

diagnosis. Lymph node blocks on the neck as an initial

presentation are not frequent, appearing in 3 to 20% of cases.

The topographic distribution of lymph node metastasis in

the neck usually is dependent on the tumor site, contiguity

and high number of capillaries.

9-11

However, invasion of

the parts with rich lymphatic network, such as the oral cavity

and nasopharynx, increases the risk of lymph node

metastases.

In majority of patients, this cancer is diagnosed in

advanced stages, making it difficult to determine the origin

of the neoplasm. Although the majority of maxillary sinus

carcinomas are locally advanced at diagnosis because its

symptoms are nonspecific and these tumors tend to remain

localized to maxilla for a long time and, during evolution,

they invade adjacent structures.

4,12

The most effective

barrier against tumors propagation is the integrity of the

periosteum that is particularly more resistant in two critical

areas: The skull base and orbit.

13

Destruction of maxillary sinus walls, especially the

inferior antral wall, can be identified by panoramic

radiography. In advanced cases, this imaging modality may

not show evidence of early bone destruction. CT and

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the examination of

choice in such situation. The primary reason for advising

CT and MRI studies in cases of maxillary sinus carcinoma

is for better characterizing the invasion of structures beyond

the site of origin. On CT studies, all of the cases present as

soft tissue masses in the maxillary sinus cavity, with 70 to

90% of cases evidencing bony destruction. CT provides

more details of bone involvement than MRI. At MRI, these

tumors present middle signal intensity on T1-weighted

images and high intensity signal on T2-weighted images,

and this method is of help in the evaluation of the posterior

cranial fossa, orbit and perineural/perivascular dissemi-

nation, allowing the differentiation between retained

secretions and neoplastic tissue.

3,14

CT helped us in arriving at preliminary diagnosis, but

histopathological examination of biopsied tissue gave a

definitive diagnosis. However, detailed analysis of

histological findings is beyond the scope of this article.

When formulating a differential diagnosis for maxillary

sinus carcinoma, it is mandate to include primary sinonasal

neoplasms (e.g. sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma,

nasopharyngeal carcinoma, lymphoma, esthesioneuro-

blastoma, primary sinonasal melanoma and adenocarcinoma

of minor salivary gland origin) and metastatic disease.

15

Treating maxillary sinus cancer is challenging because of

the crowded anatomy, proximity of critical structures, such

as the eye and the brain, which preclude wide surgical

excision and high-dose radiotherapy. The clinical course is

indolent at most and low incidence of malignant disease

here, which makes a low index of suspicion, the majority

of cancers of antrum are seen in a late or moderately

advanced stage at the time of diagnosis. Combined-modality

therapy consisting of surgery and radiotherapy with or

without intra-arterial chemotherapy is generally used for

the treatment. Local control is a particularly difficult

problem, with the majority of failures occurring at the

primary site. Radiotherapy is accepted as a palliative method

in inoperable cases.

16,17

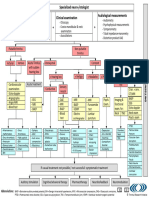

Ohngrens line is the theoretical plane joining medial

canthus of the eye with the angle of the mandible. This line

divides the maxilla into the infrastructure and superstructure

(Fig. 6). It was originally described by Dr Ohngren in 1930

to delineate the limits of resectability of a tumor in the

maxillary sinus. Tumors superoposterior to Ohngrens line

were more likely to involve the orbit, ethmoid and

pterygopalatine fossa. Malignancy behind Ohngrens line

is regarded to carry a much poorer prognosis because of the

rapid spread to the orbit and middle cranial fossae.

18

Maxillary sinus is at cross roads of dentistry and

otorhinolaryngology occupying a strategic position, as it is

connected directly to nasal cavity and indirectly to oral

cavity and maxillary alveolus. Oral diagnosticians should

be aware of the clinical signs and symptoms that might lead

one to suspect a malignant tumor might be relatively

nonspecific, potentially leading to a delay in diagnosis.

Therefore, it is important for the oral diagnostician to

maintain a high index of suspicion to allow for early

Fig. 6: Diagrammatic representation of Ohngrens line

Vijeev Vasudevan et al

254

JAYPEE

recognition and referral of these patients. One should have

eagles eye in all cases involving swellings of the head and

neck. In the presence of signs, such as pain and swelling

with associated paresthesia, or if conventional therapy fails

to resolve the swelling rapidly, prompt referral for biopsy

is needed to arrive at definitive diagnosis. It is mandate to

advise advanced imaging techniques, such as CT and MRI,

when conventional radiography fails to help in diagnosis at

the early stage of disease.

REFERENCES

1. Nunez F, Suarez C, Alvarez I, Losa J L, Barthe P, Fresno M.

Sino-nasal adenocarcinoma: Epidemiological and clinico-

pathological study of 34 cases. J Otolaryngol 1993;22(2):

86-90.

2. Sharma S, Sharma SC, Singhal S, et al. Carcinoma of the

maxillary antrum. A 10-year experience. Ind J Otolaryngol

1991;43:191-94.

3. Som PM, Brandwein M. Sinonasal cavities. Inflammatory

diseases, tumors, fractures and postoperative findings. In: Som

PM, Hugh D (Eds). Head and neck imaging (3rd ed). St Louis:

Mosby 1996;57.

4. Manrique RD, Deive LG, Uehara MA, Manrique RK, Rodriguez

J L, Santidrian C. Maxillary sinus cancer review in 23 patients

treated with postoperative radiotherapy. Acta Otorhinolaryngol

Esp 2008;59(1):6-10.

5. Hone SW, OLeary TG, Maguire A, Burns H, Timon CI.

Malignant sinonasal tumors: The Dublin Eye and Ear Hospital

experience. Ir J Med Sci 1995;164(2):139-41.

6. Selden HS, Manhoff DT, Hatges NA, Michel RC. Metastatic

carcinoma to the mandible that mimicked pulpal/periodontal

disease. J Endod 1998;24(4):267-70.

7. Georgiou AF, Walker DM, Collins AP, Morgan GJ , Shannon

J A, Veness MJ . Primary small cell undifferentiated

(neuroendocrine) carcinoma of the maxillary sinus. Oral Surg

Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2004;98(5):572-78.

8. Morse DR. Infection-related mental and inferior alveolar nerve

paresthesia: Literature review and presentation of two cases. J

Endod 1997;23(7):457-60.

9. Stern SJ , Hanna E. Cancer of nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses.

In: Meyer EN, Suen J Y (Eds). Cancer of the head and neck (3rd

ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders 1996;205-33.

10. Shibuya H, Yasumoto N, Gomi N, Yamada I, Ohashi I, Suzuki

S. CT features in second cancers of the maxillary sinus. Acta

Radiol 1991;32:105-09.

11. Donald PJ . Intranasal and paranasal sinus carcinoma. In:

Thawley SE, Pange WR (Eds). Comprehensive management of

the head and neck tumors. Philadelphia: WB Saunders 1987;94.

12. Frich J C. Treatment of advance squamous cell carcinoma of the

maxillary sinus. Int J Radiat Oncol 1982;8:1452-59.

13. Kimmelman CP, Korovin GS. Management of paranasal sinus

neoplasms invading the orbit. Otolaryngol Clin North Am

1988;21:77-92.

14. Maroldi R, Farina D, Battaglia G, Maculotti P, Nicolai P, Chiesa

A. MR of malignant nasosinusal neoplasms. Frequently asked

questions. Eur J Radiol 1997;24:181-90.

15. Goldenberg D, Golz A, Fradis M, Martu D, Netzer A, J oachims

HZ. Malignant tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses: A

retrospective review of 291 cases. Ear Nose Throat J

2001;80(4):272-77.

16. Itami J , Uno T, Aruga M, Ode S. Squamous cell carcinoma of

the maxillary sinus treated with radiation therapy and

conservative surgery. Cancer 1998;82:104-07.

17. Konno A, Ishikawa K, Terada N, Numata T, Nagata H, Okamoto

Y. Analysis of long-term results of our combination therapy for

squamous cell cancer of the maxillary sinus. Acta Otolaryngol

Suppl 1998;537:57-66.

18. Ohngren LG. Malignant tumors of the maxilla-athmoid region.

Acta Otol Suppl 1933;19:1-476.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Vijeev Vasudevan

Professor and Head, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology

Krishnadevaraya College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Bengaluru

Karnataka, India

S Kailasam

Professor and Head, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology

Ragas Dental College and Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

MB Radhika

Professor and Head, Department of Oral Pathology, Krishnadevaraya

College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Manjunath Venkatappa (Corresponding Author)

Senior Lecturer, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology

Krishnadevaraya College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Bengaluru

Karnataka, India, e-mail: manjuv79@gmail.com

Devaraju Devaiah

Senior Lecturer, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology

Krishnadevaraya College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Bengaluru

Karnataka, India

TG Shrihari

Senior Lecturer, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology

Krishnadevaraya College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Bengaluru

Karnataka, India

M Sudhakara

Senior Lecturer, Department of Oral Pathology, Krishnadevaraya

College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Ghanie Irwan 2019 J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1246 012019Document9 paginiGhanie Irwan 2019 J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1246 012019mellysa iskandarÎncă nu există evaluări

- GHSB2024 Superficial Structures of The Neck and Posterior TriangleDocument5 paginiGHSB2024 Superficial Structures of The Neck and Posterior Trianglekang seulgi can set me on fire with her gaze aloneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Therefore "Weakness" DOES NOT Help To Establish Whether It Is UMN or LMN lesion-FOLLOWING Pattern of Signs Help Us To EstablishDocument66 paginiTherefore "Weakness" DOES NOT Help To Establish Whether It Is UMN or LMN lesion-FOLLOWING Pattern of Signs Help Us To EstablishBaishakhi ChakrabortyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wells Partial Denture ProsthodonticsDocument10 paginiWells Partial Denture Prosthodonticsthesabarmo100% (1)

- TRI Tinnitus FlowchartDocument1 paginăTRI Tinnitus FlowchartAdvocacia VitóriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- RespiratoryanatomyDocument5 paginiRespiratoryanatomyMary♡Încă nu există evaluări

- INTERNS NOTES - OtorhinolaryngologyDocument15 paginiINTERNS NOTES - OtorhinolaryngologyKarl Jimenez SeparaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Direct Gingivoperiosteoplasty With PalatoplastyDocument6 paginiDirect Gingivoperiosteoplasty With PalatoplastyAndrés Faúndez TeránÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cleft Lip DR RituDocument82 paginiCleft Lip DR RituRitu SamdyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Skills Cranial Nerves I To VI Students Copy 2019Document4 paginiClinical Skills Cranial Nerves I To VI Students Copy 2019carlosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 11 Sense OrgansDocument18 paginiChapter 11 Sense OrgansMichael Oconnor100% (2)

- Lec 1 Functional Areas of Cerebral CortexDocument37 paginiLec 1 Functional Areas of Cerebral CortexMudassar RoomiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Function of TongueDocument11 paginiThe Function of TongueAndrea LawÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 1 PDF People PDFDocument12 paginiUnit 1 PDF People PDFCosmic LatteÎncă nu există evaluări

- HearingDocument15 paginiHearingdisha mangeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 008 164 Anatomy of Thyroid Gland PDFDocument10 pagini008 164 Anatomy of Thyroid Gland PDFWILLIAMÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of Intratympanic Dexamethasone in Sudden Sensorineural Hearing LossDocument5 paginiThe Role of Intratympanic Dexamethasone in Sudden Sensorineural Hearing LossAditya HendraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Salivary GlandsDocument97 paginiSalivary GlandsSwati George100% (2)

- Chapter 8-SPECIAL SENSESDocument5 paginiChapter 8-SPECIAL SENSESrishellemaepilonesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Weinberg2001 THERAPEUTIC BIOMECHANICS CONCEPTS AND CLINICAL PROCEDURES TO REDUCE IMPLANT LOADING. PART II - THERAPEUTIC DIFFERENTIAL LOADINGDocument9 paginiWeinberg2001 THERAPEUTIC BIOMECHANICS CONCEPTS AND CLINICAL PROCEDURES TO REDUCE IMPLANT LOADING. PART II - THERAPEUTIC DIFFERENTIAL LOADINGPablo Gutiérrez Da VeneziaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PonsDocument61 paginiPonsAyberk ZorluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Occlusion in FPDDocument38 paginiOcclusion in FPDDRPRIYA007100% (4)

- Anatomy of The EarDocument10 paginiAnatomy of The EarJP SouaidÎncă nu există evaluări

- TAOMS20 Abstract BookDocument238 paginiTAOMS20 Abstract BookTaha ÖzerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anatomy Topography of The EyeDocument46 paginiAnatomy Topography of The Eyeikayapmd100% (1)

- HANDOUT Laryngeal-MassageDocument7 paginiHANDOUT Laryngeal-MassageAnca OÎncă nu există evaluări

- MRI & CT of Facial Bones PDFDocument53 paginiMRI & CT of Facial Bones PDFdr_340802071Încă nu există evaluări

- Assessing The Nose and Sinuses: Return Demonstration Tool Evaluation ForDocument3 paginiAssessing The Nose and Sinuses: Return Demonstration Tool Evaluation Forclint xavier odangoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient Type: OPD: TSH Test ReportDocument1 paginăPatient Type: OPD: TSH Test ReportVeenu SehrawatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kadasne's Textbook of Anatomy (Clinically Oriented) VOLUME 3 Head, Neck, Face and Brain (2009) (PDF) (UnitedVRG)Document365 paginiKadasne's Textbook of Anatomy (Clinically Oriented) VOLUME 3 Head, Neck, Face and Brain (2009) (PDF) (UnitedVRG)Ahmad YÎncă nu există evaluări