Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

TMP B4 EC

Încărcat de

FrontiersDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

TMP B4 EC

Încărcat de

FrontiersDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25 www.brill.

nl/jocc

Metacognition of Problem-Solving Strategies

in Brazil, India, and the United States

C. Dominik Güss

Brian Wiley

Department of Psychology, University of North Florida

dguess@unf.edu

Abstract

Metacognition, the observation of one’s own thinking, is a key cognitive ability that allows humans

to influence and restructure their own thought processes. The influence of culture on metacognitive

strategies is a relatively new topic. Using Antonietti’s, Ignazi’s and Perego’s questionnaire on

metacognitive knowledge about problem-solving strategies (2000), five strategies in three life

domains were assessed among student samples in Brazil, India, and the United States (N=317),

regarding the frequency, facility, and efficacy of these strategies. To investigate cross-cultural

similarities and differences in strategy use, nationality and uncertainty avoidance values were

independent variables. Uncertainty avoidance was expected to lead to high frequency of decision

strategies. However, results showed no effect of uncertainty avoidance on frequency, but an effect

on facility of metacognitive strategies. Comparing the three cultural samples, all rated analogy as

the most frequent strategy. Only in the U.S. sample, analogy was also rated as the most effective and

easy to apply strategy. Every cultural group showed a different preference regarding what

metacognitive strategy was most effective. Indian participants found the free production strategy to

be more effective, and Indian and Brazilian participants found the combination strategy to be more

effective compared to the U.S. participants. As key abilities for the five strategies, Indians rated

speed, Brazilians rated synthesis, and U.S. participants rated critical thinking as more important

than the other participants. These results reflect the embedded nature and functionality of problem-

solving strategies in specific cultural environments. The findings will be discussed referring to an

eco-cultural framework.

Keywords

Metacognition, Problem Solving, Culture, Decision Making

Metacognition, thinking about one’s own thinking, is a key cognitive ability.

It allows humans to control and restructure their own thoughts and it plays

a crucial role in learning and problem solving (Akama & Yamauchi, 2004;

Dörner, Kreuzig, Reither, & Stäudel, 1983). The effects of metacognition on

© Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2007 DOI: 10.1163/156853707X171793

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 1 3/14/07 8:32:39 PM

2 C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25

problem solving have been widely studied in the school context with children

(e.g. Flavell, 1976). Many training programs have been developed and evaluation

of these programs shows positive effects of metacognitive activities on learning

(e.g., Lin, 2001) regardless of interindividual differences of participants (e.g.

regarding achievement see Mevarech & Kramarski, 2003) or certain disabilities

(e.g. regarding learning and attention disorders see Lauth, 1996).

Metacognition is especially important during the stages of problem solving:

realization that there is a problem, definition of goals, mental representation of

the problem, decision on overall strategy, information collection, prediction of

further developments, planning and evaluation of possible solutions, decision

making, monitoring problem solving, action, and evaluation of outcome

(Dörner, 1996; Duncker, 1945; Sternberg, 2003, p. 361). Metacognition is a

part of these problem-solving stages, especially during monitoring and evalua-

tion of solutions and outcomes. Stage theories often suggest a linear process of

problem solving: we proceed through stages in a sequential order, one stage at a

time. However, in every problem situation all of these stages are not equally

important and these stages are not followed sequentially in every problem situa-

tion. Rather, they are interconnected, and oftentimes problem solving requires

returning to a previous stage and resuming the process from that point or going

through those stages in a non-sequential, recursive order.

As the following brief summary shows, most theories on problem solving

focus on the stage of planning and evaluation of possible solutions. We follow

here Antonietti’s, Ignazi’s, and Perego’s (2000) discussion of five different prob-

lem-solving approaches. A first approach argues that problem solving consists

mainly of generation of many ideas (e.g. Johnson-Laird, 1993). A second

approach assumes that problem solving consists mainly of new combinations

of existing knowledge (e.g. Simonton, 1984). A third approach highlights

the power of analogies in problem solving (e.g. Vosniadou & Ortony, 1989).

A fourth approach sees problem solving as transforming an initial undesired

state into a desired goal state through a series of operators as described, for exam-

ple, in the means-end analysis (Newell & Simon, 1972). Finally, problem solving

can be viewed primarily as restructuring the representation of the problem situ-

ation (Wertheimer, 1959). The first four approaches focus on how to arrive at a

possible and promising solution. The last approach, the Gestalt approach, high-

lights the problem representation aspect in problem solving. In all of

these approaches, metacognition plays an important role: for generating new

ideas, producing new combinations of knowledge, thinking of analogies, coming

up with a specific combination of operators, and restructuring the problem rep-

resentation. Antonietti et al. (2000) developed a questionnaire assessing meta-

cognition of these five problem-solving strategies in three different problem

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 2 3/14/07 8:32:41 PM

C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25 3

situations: interpersonal, practical, and study problems. The authors could

show that each strategy’s frequency, efficacy and facility of implementation are

highly related.

Metacognition can enhance problem-solving performance not only in well-defined

problems like the tower of Hanoi (e.g. Beradi-Coletta, Buyer, Dominowski, &

Rellinger, 1995) or puzzle problems (Akama & Yamauchi, 2004), but also in

complex and dynamic, ill-defined problems (e.g. Tisdale, 1998). Metacognition

becomes especially important in ill-defined problems as the problem solver can-

not rely as much on domain-specific knowledge (Land, 2004). Thus, the focus

on the problem-solving process becomes more relevant. To reflect on this pro-

cess leads to a deeper understanding of the problem and to a more flexible and

successful approach to solve the problem. For example, in the information col-

lection stage, Schmidt and Ford (2003) demonstrated that metacognitive activi-

ties go hand in hand with more successful acquisition of relevant knowledge.

They showed this using the real world problem of creating web pages. Chi, Bas-

sok, Lewis, Reimann & Glaser (1989) showed that successful problem solvers

more often reflect on their own problem solving. Experts compared to novices,

for example, are more skilled in allocating their time during problem solving and

realizing when they make errors (Carlson, 1997; Glaser & Chi, 1988). Engaging

in metacognitive activities, problem solvers become aware of their strengths, but

also of their limitations (Bransford, Brown, & Cooking, 1999) and suppressing

metacognitive processes during problem solving can lead to a decrease in perfor-

mance (Bartl & Dörner, 1998).

Culture, Problem Solving, and Metacognition

Although metacognition has been studied widely in western cultures, it has

not yet been thoroughly studied cross-culturally (see Davidson, 1994). Several

cross-cultural studies on problem solving, coping with conflicts, planning, and

decision-making in different cultures (Mann, Radford, Burnett, Ford, Bond,

Leung, Nakamura, Vaughan, & Yang, 1998; see Weber, & Hsee, 2000 for

an overview on decision making and culture) highlight different strategic

approaches and thus would indicate differences in metacognitive problem-

solving strategies as well. For example, planning behavior in Brazil, India,

and the U.S. was compared in several studies using problem scenarios with

open-ended questions (Güss, 2000; Strohschneider & Güss, 1998). Brazilian

participants accepted the problem situations as they were. They developed short

plans following only one direction. Most of their outcome expectations were

hopeful, a result that goes hand in hand with the description of Brazilian opti-

mism in other studies (Stubbe, 1987; Scheper-Hughes, 1990). Brazilian planning

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 3 3/14/07 8:32:41 PM

4 C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25

and problem solving have also been described as creative (Fleith, 2002) often

using improvisation (see Brazilian term “jeito” in Stubbe, 1987).

Indian participants proved similar to the Brazilians in that they accepted the

problem situation and were optimistic with regards to the plans’ outcomes.

However, Indian plans were longer. Their optimism and detailed plans were

quite contrary to the western stereotype that describes Indians as “fatalistic.” In

a study on Indian problem solving, Indian students showed a flexible approach,

adjusting to the changes in the situation (Güss, 2002). This result goes hand in

hand with the description of India as a high context culture (Hall, 1976): behav-

iors are highly selected according to the specific context characteristics. Many

Western individualistic cultures are low context cultures, where behaviors are

less influenced by the context.

American students developed short plans, but their plans consisted of different

alternatives and many questions (Glencross & Güss, 2004). Americans were

more skeptical about their future expectations. In other studies, Americans

showed a preference for assertive tactics in dealing with problems (Ohbuchi,

Fukushima, & Tedeschi, 1999). The described cross-cultural difference in plan-

ning and problem solving suggest that Brazilians, Indians, and Americans also

use different metacognitive strategies during these processes.

It is about time we defined culture before further discussion on cross-cultural

research on planning and problem-solving. Culture is a term that is difficult to

grasp and has been defined in many different ways (see Kroeber & Kluckhohn,

1963). Under a relativistic perspective expressed by cultural psychologists, cul-

ture is often seen as a whole that cannot be divided into separate parts. Most

cross-cultural psychologists, on the other hand, see culture as a set of separate

variables (Berry, Poortinga, Segall, & Dasen, 2002). In order to understand cul-

tural differences, such variables should then be studied in quasi-experimental

designs. Such studies would not only describe differences between cultures, but

also answer the question why certain cultures differ. For our further discussion,

culture can be defined as implicit and explicit shared knowledge that is transmit-

ted from generation to generation (Smith & Bond, 1998).

Cultural differences in problem solving might be due to differences in this

implicit and explicit knowledge; specifically in goals, means to achieve these

goals, and the transfer of goals and means to other situations (Saxe, 1994). Cul-

tural differences in the stability and predictability of the environment, and in

basic values such as individualism and collectivism might influence the selection

of goals and means, and the degree of metacognitive engagement (Strohsch-

neider & Güss, 1998). Whereas one cultural environment may allow for detailed

information collection and reflection, another cultural environment may

demand quick action. Whereas one culture requires strategic planning for nego-

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 4 3/14/07 8:32:41 PM

C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25 5

tiation with in-group members before making decisions, another culture would

require individual decision making without much consideration of the opinion

of the in-group.

The use of different metacognitive strategies in different cultures can be a

result of different socialization processes. School institutions, parents, teachers,

and peers may play different roles in this socialization process in different

cultures (Carr & Borkowski, 1989). The authors also stress how different moti-

vational orientations in different cultures can influence when and how someone

engages in metacognitive activities. Three empirical studies highlight cross-

cultural differences in metacognition in the educational context. A first study

comparing German and American parents showed that Germans reported more

frequent instruction of metacognitive strategies at home, and German children

showed use of these strategies more than American children did (Carr, Kurtz,

Schneider, Turner, & Borkowski, 1989). Second, Davidson and Freebody (1988)

found differences on metacognitive knowledge about school learning of Austra-

lian children from varied ethnicities. Participants’ metacognitive knowledge

increased with the occupational status of participants’ fathers. Third, McCafferty

(1992) compared the metacognitive activity of students learning English as a

second language between two small samples of Hispanic and Oriental college

students. Hispanics showed more metacognition during communication in the

second language.

Although these three studies show cross-cultural differences in metacogni-

tion, they are not related to problem-solving processes. The current study then is

an attempt to investigate cross-cultural differences in metacognition, specifically

in metacognition of problem-solving strategies.

Situatedness or Generality of Metacognition

The fact that research shows cross-cultural differences in problem solving and

metacognition is important. Cross-cultural research previously described along

with other studies (e.g. Veenman, Wilhelm, & Beishuizen, 2004) suggest that

metacognitive processes are more general cognitive preferences. On the other

hand, one might argue that metacognitive strategies are influenced by the specific

demands of the situation (see “situatedness” described by Rohlfing, Rehm, &

Goecke, 2003). Whereas some people, for example, might engage in metacogni-

tion when confronted with a problem at work, they might not engage in meta-

cognition and problem solving when they are confronted with a private problem.

Dunlosky (1998) argued that further research should address this important

question of whether metacognitive processes are indeed different in different

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 5 3/14/07 8:32:41 PM

6 C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25

problem domains or more general cognitive styles as there is not yet enough

empirical evidence to support either side.

Uncertainty Avoidance and Problem-Solving Strategies

One cultural variable that might possibly explain differences in metacognitive

problem solving strategies is values. Basic value dimensions are one of the most

widely studied aspects of different cultures (e.g. Rokeach, 1973; Schwartz, 1994;

Smith, Peterson, Schwartz, 2002). A value can be defined as “a conception,

explicit or implicit, distinctive of an individual or characteristic for a group, of

the desirable which influences the selection from available modes, means and

ends of actions” (Kluckhohn & Murray, 1953, p. 59). Under a cognitive perspec-

tive, values can be seen as abstract goals acquired during the socialization and

enculturation processes. These goals are guiding principles for the selection of

subgoals and for the selection of means to achieving those subgoals (Rokeach,

1973). Therefore, values can guide the problem-solving process. One of the basic

value dimensions studied cross-culturally is uncertainty avoidance. Uncertainty

avoidance is “the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by

uncertain or unknown situations” (Hofstede, 2001, p. 161). Hofstede (2001)

distinguishes three components of uncertainty avoidance: rule orientation,

employment stability, and stress. High uncertainty avoidance is expressed in

strong rule orientation (Rule orientation stands for agreement and acceptance of

existing norms and rules), preference for employment stability, and high scores

for stress. High uncertainty avoidance might go hand in hand with high engage-

ment in metacognitive and problem-solving activities. To cope with the threat

of uncertainty, people might vary in the degree they engage in metacognitive

activities.

Research Questions

This study investigates the following questions. Do people from different cultures

differ in their metacognitive problem solving strategies? More specific questions

relate to our cultural samples: Do American participants show little variance

in metacognitive styles across situations, as the U.S. has often been characterized

as an individualistic (Hofstede, 2001), low-context culture (Hall, 1976)? Do

Indian participants show high variance in metacognitive problem solving

styles across situations, as India can be characterized as a high-context culture?

Do Brazilian participants show lower frequencies of metacognitive strategies

(Güss, 2000) as Brazilian thinking has been described as optimistic and more

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 6 3/14/07 8:32:42 PM

C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25 7

focused on the present (Güss, Glencross, Tuason, Summerlin, & Richard, 2004;

Strohschneider & Güss, 1998)? Do cultures understand metacognitive problem-

solving strategies in a similar way and are the required abilities for a strategy the

same across cultures? Do cultural values, specifically uncertainty avoidance,

influence selection of problem-solving strategies? Does high uncertainty avoid-

ance lead to more frequent use of problem-solving strategies? Are frequency,

efficacy, and facility of reported strategy use highly related as shown by Anto-

nietti et al. (2000)? Are reported problem solving-strategies situation-specific or

similar across situations?

Method

Participants

Participants were sampled from three countries: the U.S.A., Brazil, and India. As

this study is a part of a larger project, the selection of these countries was

influenced by differences on the individualism-collectivism dimension. If we can

couch it in oversimplified terms, it can be said that the U.S. represents an indi-

vidualistic society, Brazil represents a collective society (Hofstede, 2001), and

India represents the middle of the individualistic-collectivistic continuum (Sinha

& Tripathi, 1994). Hofstede’s (2001) data from the late 1960s and early 1970s

assessing uncertainty avoidance in 50 countries and three regions with three

questions show average uncertainty avoidance for Brazil (76), and low uncer-

tainty avoidance for the U.S. (46) and for India (40). In the rank order of uncer-

tainty avoidance among 53 countries, Brazil has rank 21/22, India rank 45, and

the U.S. rank 43.

We intended to gather comparable samples across cultures regarding age,

study subject, and gender. Participants were 133 U.S., 97 Brazilian, and 97 Indian

students. The U.S. sample had a gender breakdown of 66% female and 34% male,

with an average age of 22.5. The Brazilian sample had a gender breakdown of

72% female and 28% male with an average age of 23.8. The Indian sample had a

gender breakdown of 52% female and 48% male with an average age of 22. Over

all three samples, 68% were studying psychology, 12% were studying business,

12% were studying social sciences, and 8% were studying natural sciences.

Measures

Uncertainty avoidance was measured with six items derived from Hofstede

(2001, p. 150). They were slightly modified since participants in this study

were students and not managers. The items referred either to the educational or

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 7 3/14/07 8:32:42 PM

8 C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25

the work environment (see Appendix A), e.g. “Company rules should not be

broken – even when the employee thinks it is in the company’s best interests” or

“How often do you feel nervous or tense at class?” Responses were scored on a

five-point scale. Several alpha coefficients for this scale were calculated including

only two items, three, four or five items for the overall sample and for the cul-

tural subsamples. The alpha coefficients vary from .05 to .50. Combining the

items referring to anxiety, work preferences, and rule orientation leads to low

alpha coefficients. One reason for this finding might be cross-cultural differences

regarding work experience. In fact, 82% of the U.S. participants, 64% of the Bra-

zilian participants, and 22% of the Indian participants have work experience

longer than one year (summarizing answers that indicate one to two years work

experience and answers indicating more than two years work experience). Eigh-

teen percent of the U.S. participants, 36% of the Brazilian participants, and 78%

of the Indian participants have work experience of less than one year. These

differences between the samples regarding work experience are statistically

significant, χ2 (6, N = 313) = 78.34, p < .001.

The highest alpha coefficient of .80 was found by calculating the reliability

of the first two items only (see Appendix A: “Company rules should not be bro-

ken – even when the employee thinks it is in the company’s best interests.” “Uni-

versity rules should not be broken – even when the student thinks it is in the

university’s best interests.”). These two items refer to rule orientation in compa-

nies and universities. Rule orientation is only one of the three uncertainty avoid-

ance dimensions of Hofstede. The other two dimensions were employment

stability and stress. For the two items assessing rule orientation, the alpha

coefficient was found to be .80 overall, .88 for the U.S. sample, .79 for the Brazil-

ian sample and .67 for the Indian sample. The same alpha coefficients result

when using grand mean centered item scores. These alpha coefficients are satis-

factory and further data analysis refers to uncertainty avoidance as assessed by

these two items.

Five different metacognitive strategies: free production, analogy (for an in-

depth case study on analogy and scientific discovery see Spranzi, 2004), step by

step, visualization, and combination were assessed with items that described

each strategy. Then the participants were asked to rate the frequency, efficacy,

and facility of that strategy on a scale from one to five across three situations:

interpersonal, study, and practical problems (Antonietti, Ignazi, & Perego, 2000).

Frequency refers to how often the strategy is used, efficacy refers to how effective

the strategy is, and facility refers to how easy it is to apply the strategy. Partici-

pants were also asked to indicate which of eight mental abilities were associated

with the metacognitive strategy. These mental abilities were creativity, speed,

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 8 3/14/07 8:32:42 PM

C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25 9

synthesis, critical thinking, accuracy, memory, analysis, logical reasoning (see

Appendix B for an example).

In order to make data from the U.S., the Brazilian, and the Indian sample

comparable, they were standardized using grand mean centering (Fischer, 2004).

The overall mean score of all 45 responses of each cultural sample was calculated

and subtracted from every single individual item score. The overall mean score of

all answers was 3.29 in the US sample, 3.35 in the Brazilian sample, and 3.38 in

the Indian sample. Although the three groups did not differ significantly, F(2,

324)=1.04, p = .36, we still thought that the following statistical comparisons

using grand mean centered scores would be more accurate.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from universities through announcements in classes

and posted flyers. Participants were scheduled to complete the questionnaires in

groups. An experimenter was available to answer any questions that the partici-

pants might have had about the research materials.

Results

Age, Gender, Metacognitive Strategies, and Uncertainty Avoidance.

An alpha level of .05 was used for all statistical tests. A significant difference in

the age of participants was found, F(2, 326) = 4.59, p = .01, with Brazilian stu-

dents (M=23.8) being older than Indian participants (M=22.0). The U.S. sam-

ple had an average age of 22.5 years. Differences in age and gender are related to

the make-up of student populations in the different countries. However, no cor-

relation between age and the 45 metacognitive strategy variables was statistically

significant. Age did also not correlate significantly with uncertainty avoidance.

The gender distribution in India was significantly different from the distribu-

tions in the United States and Brazil, F(2, 326) = 7.51, p = .001. Comparing 204

female and 116 male participants, significant gender differences were found in

five out of 45 variables, namely free production-interpersonal-frequency,

t(318)=2.98, p = .003, Mm=2.91, SDm=1.23 and Mf =3.32, SDf = 1.19 before

grand mean centering; analogy-practical-easiness t(316)=2.67, p = .008;

Mm=3.43, SDm=1.10 and Mf=3.75, SDf = .98 before grand mean centering;

analogy-study-frequency, t(319)=2.30, p = .022, Mm=3.56, SDm=1.11 and

Mf =3.85, SDf = 1.10 before grand mean centering; analogy-study-usefulness,

t(319)=2.75, p = .006, Mm=3.59, SDm=1.13 and Mf =3.93, SDf = 1.06 before

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 9 3/14/07 8:32:42 PM

10 C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25

grand mean centering; and step-by-step-study-usefulness, t(317)=2.29, p = .02,

Mm=3.68, SDm=1.02 and Mf =3.95, SDf = 1.02 before grand mean centering; In

these five variables, female participants always had higher scores than male par-

ticipants. We included gender as a covariate in further analyses of those five vari-

ables where significant differences were found. No significant gender differences

were found in the cumulated scores across problem situations and across fre-

quency, efficacy, and facility. No significant gender differences were found

regarding uncertainty avoidance.

Relation of Frequency, Efficacy, and Facility of Problem-Solving Strategy

To investigate if frequency, efficacy, and facility of problem-solving strategy are

related, Pearson correlations between these different scores in each strategy and

type of problem were calculated (see Table 1). All correlations were significant at

the 1% level and ranged between .32 and .72. The average of the Frequency-

Efficacy correlations was .63, the average of the Frequency-Facility correlations

was .54, and the average of the Efficacy-Facility correlations was .48. The results

show that the frequency of strategy use is related to its perceived efficacy and its

perceived facility of implementation.

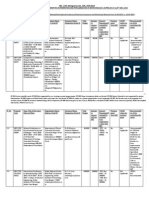

Table 1

Correlations of Frequency, Efficacy, and Facility Scores

for Each Type of Problem and Each Strategy.

N=323 to 327 Frequency- Frequency- Efficacy-

Efficacy Facility Facility

Free production

Interpersonal problems .60*** .40*** .32***

Practical problems .69*** .46*** .43***

Study problems .62*** .46*** .47***

Analogy

Interpersonal problems .53*** .51*** .44***

Practical problems .62*** .47*** .48***

Study problems .67*** .58*** .57***

Step-by-Step

Interpersonal problems .68*** .71*** .57***

Practical problems .59*** .58*** .45***

Study problems .54*** .53*** .41***

Visualisation

Interpersonal problems .72*** .61*** .58***

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 10 3/14/07 8:32:42 PM

C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25 11

Table 1 (cont.)

N=323 to 327 Frequency- Frequency- Efficacy-

Efficacy Facility Facility

Practical problems .68*** .56*** .51***

Study problems .72*** .59*** .60***

Combination

Interpersonal problems .65*** .59*** .41***

Practical problems .60*** .48*** .43***

Study problems .61*** .54*** .50***

* p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001

Cross-Cultural Use of Metacognition

Statistical analyses revealed differences in the use of metacognitive strategies

across cultures. Over all five strategies the differences in mean frequency were

not significant, F(2, 308) = 2.65, p = .07, ηp2=.02). The means were 3.52

(SD=.72; grand mean centered M=.14, SD=.71) in the Indian sample, 3.34

(SD=.52; grand mean centered M=−.01, SD=.52) in the Brazilian sample and

3.25 (SD=.55; grand mean centered M=−.04, SD=.55) in the U.S. sample.

An ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test to determine mean score differences

was used to detect differences in how frequently participants reported using

specific strategies across cultures. The independent variable was culture with

three levels: India, Brazil, and the United States. The dependent variables were

free production, analogy, step by step, visualization, and combination summa-

rized across situations. The free production method (F(2, 314) = 4.76, p = .01,

ηp2=.03) was used most frequently in India, followed by Brazil and the United

States. Indian participants had significant higher scores then Brazilian and U.S.

participants. The combination method (F(2, 314) = 5.75, p = .004, ηp2 =.02)

was used significantly more frequently in India and Brazil then in the United

States. The analogy method (F(2, 314) = 3.04, p = .05, ηp2 =.03) was used most

frequently in the United States, followed by Brazil and then India with significant

differences between Unites States and India (see Figure 1). No significant

differences regarding frequency were found in the step by step and visualization

strategy for all situations.

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 11 3/14/07 8:32:43 PM

12 C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25

Frequency of Strategy Use Across Cultures

4.00

3.50

3.00

2.50

USA (n=133)

2.00 Brazil (n=97)

India (n=96)

1.50

1.00

0.50

0.00

Free Analogy Step-by-Step Visualization Combination

Production

Figure 1. Frequency of Strategy Use Across Cultures

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 12 3/14/07 8:32:43 PM

C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25 13

An ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test to determine mean score differences

was also used to detect differences in the efficacy (“usefulness”) of strategy

use across cultures. The free production method (F(2, 311) = 4.33, p = .01,

ηp2 =.03) was rated to be most useful in India, compared to Brazil and the United

States. The analogy method (F(2, 311) = 13.53, p < .001, ηp2 =.08) was regarded

as the most useful in the United States, followed by Brazil and India with

significant differences between all three countries. The step by step method (F(2,

311) = 3.46, p = .02, ηp2 =.03) was viewed most useful in Brazil, followed by the

United States and India with significant differences between Brazil and India.

The combination method (F(2, 311) = 9.41, p < .001, ηp2 =.06) was also viewed

most useful in Brazil, followed by India and the United States with significant

differences between Brazil and the United States (see Figure 2). No differences

were found in the visualization method.

The only significant difference in the facility of strategy use (“easy to apply”)

across cultures was found in the analogy category. Similar to the efficacy cate-

gory, the analogy method was regarded as the easiest to apply in the United

States compared to Brazil and India, F(2, 320) = 10.33, p < .001, ηp2 =.06.

Uncertainty Avoidance and Metacognitive Strategy Use

The three cultures differed significantly in the uncertainty avoidance scores,

F(2, 321)=3.26, p = .04, ηp2 =.02. As the scale we used consisted of two items

referring to rule orientation and did not assess the two other dimensions of

uncertainty avoidance, i.e. employment stability and stress, as described by

Hofstede (2001), we will from now on refer to rule orientation instead of uncer-

tainty avoidance. The mean scores for the two rule orientation scores were

5.18 (SD=2.20) (grand mean centered −.35, SD=1.10) for the U.S. sample; 6.51

(SD=2.01) (grand mean centered −.03, SD=1.01) for the Brazilian sample; and

5.17 (SD=2.34) (grand mean centered −.39, SD=1.17) for the Indian sample.

High scores stand for low rule orientation. Although Brazilian participants

showed the lowest rule orientation, a Tukey post-hoc test comparing grand mean

centered scores shows only marginal significant differences between Brazil and

India (p = .06) and between Brazil and the United States (p = .07) regarding

rule orientation.

Rule orientation correlated significantly with facility over all strategies r=.13,

p = .02; with step-by-step-efficacy over all situations r = .11, p = .04; with

analogy-practical-facility r = .15, p = .01, and with visualization-study-facility,

r = .11, p = .05. Low rule orientation goes hand in hand with high facility of

several strategies and high efficacy of the step by step strategy in all situations.

The Pearson correlations of rule orientation and other metacognitive variables

varied between −.018 and .086.

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 13 3/14/07 8:32:43 PM

14 C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25

Efficacy of Strategy Use Across Cultures

4.00

3.50

3.00

2.50

USA (n=133)

2.00 Brazil (n=97)

India (n=96)

1.50

1.00

0.50

0.00

Free Analogy Step-by-Step Visualization Combination

Production

Figure 2. Efficacy of Strategy Use Across Cultures

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 14 3/14/07 8:32:43 PM

C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25 15

Impact of Situation on Metacognitive Strategy

Analyses determined that strategy selection was influenced more by culture than

by situation. The questionnaire assessed metacognition in three different situa-

tions: interpersonal problems, practical problems, and study problems. An

ANOVA with situation as independent variable and a Tukey post-hoc test to

determine mean score differences revealed that differences in situation are only

significant in the step by step method, F(2, 955) = 27.73, p < .001, ηp2 =.06.

Participants indicated that they use the step by step method more in study prob-

lems than in interpersonal and practical problems. Overall, only one significant

interaction effect between country and situation was found in the free produc-

tion method, F(4, 964) = 3.48, p = .01, ηp2 =.01. The interaction effect refers to

study problems. Compared to the other two situations, frequency in free pro-

duction in the United States was decreasing; while it was increasing in Brazil and

India (see Figure 3). These results regarding situation-specificity of metacogni-

tive strategies speak more for a general metacognitive style than for domain

specificity.

Strategy Use Across Situation and Culture

12.00

10.00

8.00

India

6.00 Brazil

USA

4.00

2.00

0.00

Combination

Combination

Combination

Visualization

Visualization

Visualization

Production

Production

Production

Step-by-

Step-by-

Step-by-

Analogy

Analogy

Analogy

Step

Step

Step

Free

Free

Free

Interpersonal Practical Study

Figure 3. Strategy Use Across Situation and Cultures

Composition and Abilities of Metacognitive Problem-solving Strategies

The understanding of metacognitive problem-solving strategies was studied

in the three different cultural samples. For every strategy, participants indi-

cated which of eight mental abilities was involved. The average of eight possible

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 15 3/14/07 8:32:43 PM

16 C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25

abilities in each of the five strategies was 18.82 (SD=6.52) in the U.S. sample,

18.80 (SD=6.30) in the Brazilian sample, and 17.91 (SD=9.35) in the Indian

sample, indicating 3 to 4 abilities marked per strategy. The main effect of culture

on the number of marked composition aspects was not significant, F(2, 322) = .50,

p = .60, ηp2 =.003. The following statistical analysis refers to the raw data. These

data were not grand mean centered. Regarding every strategy, differences were

found in at least three of the eight abilities associated with each strategy across

cultures. With respect to the free production strategy, creativity was more

important in Brazil than in India, F(2, 324) = 5.01, p = .01, ηp2 =.03. Speed was

more important in India than in the United States, F(2, 324) = 5.23,

p = .01, ηp2 =.03. Synthesis was more important in Brazil than the United States,

F(2, 324) = 3.67, p = .03, ηp2 =.02. Logical reasoning was more important in the

United States than in Brazil, F(2, 324) = 6.32, p = .002, ηp2 =.04.

With respect to the analogy strategy, creativity was more important in India

than in Brazil and the United States, F(2, 324) = 9.37, p < .001, ηp2 =.06. Speed

was more important in India than in Brazil and the United States,

F(2, 324) = 11.06, p < .001, ηp2 =.06. Synthesis was more important in Brazil

than in India and the United States, F(2, 324) = 5.89, p = .003, ηp2 =.04. Accu-

racy was more important in the United States than in Brazil and India,

F(2, 324) = 6.38, p = .002, ηp2 =.04. Memory was more important in the United

States than in Brazil and India, F(2, 324) = 18.42, p < .001, ηp2 =.10. Analysis

was more important in the United States than in India, F(2, 324) = 6.19,

p = .002, ηp2 =.04.

With respect to the step by step strategy, creativity was more important in

India than in the United States, F(2, 324) = 3.32, p = .037, ηp2 =.02. Speed was

more important in India than in Brazil and the United States, F(2, 324) = 7.55,

p = .001, ηp2 =.05. Synthesis was more important in Brazil than in the United

States, F(2, 324) = 3.34, p = .04, ηp2 =.02. Critical thinking was more important

in the United States than in India and Brazil, F(2, 324) = 14.614,

p < .001, ηp2 =.08. Accuracy was more important in Brazil than in India,

F(2, 324) = 5.09, p = .01, ηp2 =.03. Analysis was more important in Brazil than

in the United States and India, F(2, 324) = 8.98, p < .001, ηp2 =.05. Logical rea-

soning was more important in Brazil than in India, F(2, 324) = 7.88,

p < .001, ηp2 =.05.

With respect to the visualization strategy, creativity was more important in

the United States than in India, F(2, 324) = 6.90, p = .001, ηp2 =.04. Speed was

more important in India than in Brazil and the United States, F(2, 324) = 11.25,

p < .001, ηp2 =.07. Critical thinking was more important in the United States

than in India and Brazil, F(2, 324) = 5.23, p = .07, ηp2 =.03.

With respect to the combination method, creativity was more important in

Brazil than in the United States and India, F(2, 324) = 4.49, p = .01, ηp2 =.03.

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 16 3/14/07 8:32:44 PM

C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25 17

Speed was more important in India than in Brazil and the United States,

F(2, 324) = 5.58, p = .004, ηp2 =.03. Critical thinking was more important in the

United States than in Brazil, F(2, 324) = 3.10, p = .05, ηp2 =.02. Accuracy was

more important in India than in the United States, F(2, 324) = 3.05, p = .05,

ηp2 =.02.

In comparing the importance of specific mental abilities in the five different

strategies between the three different cultural groups, it is interesting to note

that Indian participants rated speed as more important than Brazilian and U.S.

participants in all five strategies. Brazilians rated synthesis as more important

than Indian and U.S. participants in the three strategies where significant

differences between cultural groups were found. U.S. participants rated critical

thinking as more important than did Indian and Brazilian participants in the

three strategies where significant differences were found.

Discussion

The main question investigated refers to cultural differences in metacognitive

problem-solving strategies. As the results show, we indeed find cross-cultural

similarities and differences in frequency, efficacy, and facility of metacognitive

strategies. In each of the five strategies frequency, efficacy, and facility were

significantly correlated. Antonietti et al. (2000) found the same result. Over all

five strategies, no cultural differences regarding frequency of strategy were found.

It was expected that Brazilians would show lower frequencies. However, Brazil-

ian presence orientation (Strohschneider & Güss, 1998) and improvisation do

not necessarily go hand in hand with lower metacognitive activity. The time

frame, but not the amount of metacognitive activity, might be different.

Analogy was the most frequently reported strategy in all three samples. Indian

participants reported more frequent use of the free production strategy, U.S. par-

ticipants more frequent use of the analogy method, and Brazilian and Indian

participants more frequent use of the combination method. The more frequent

use of the free production method in the Indian sample might be associated with

a higher context-sensitivity (Hall, 1976). The combination strategy might reflect

the Brazilian “jeito” (Stubbe, 1987), that in a specific problem situation, creative

and improvised solutions have to be found.

Every cultural group also had a different preference regarding the efficacy of

metacognitive strategy. Indian participants reported higher scores than the other

two cultural samples for the free production method, U.S. participants reported

higher scores for analogy, and Brazilian participants reported higher efficacy

scores for the step by step and combination strategy. Regarding the facility of

metacognitive strategies, all samples rated the analogy method as the most easy

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 17 3/14/07 8:32:44 PM

18 C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25

to apply. However, U.S. participants found it easier to apply than Indian and

Brazilian participants. In the U.S. sample, the analogy strategy was found most

easy to apply, most useful, and most frequently used. This was not the case in the

Brazilian and Indian sample. This result could be related to the often-described

American pragmatism. In philosophy, American pragmatism is a popular school

(Gross, 2002; Perry, 2001) that goes back to Charles Sanders Peirce and John

Dewey, and was further developed by William James (Pajares, 2003). This tradi-

tion stresses the importance of the practical outcome of ideas in the practical

culture. In a popular sense “get things done” reflects such a pragmatic attitude. A

pragmatic problem-solving approach would favor those strategies that have been

proven to work well and easy to apply.

To explain cultural differences, uncertainty avoidance was assessed. The two

questions used for further analysis only refer to rule orientation. The scale could

and should be improved. Items have to be added and the validity has to be

assessed. Besides the methodological problems with the survey, there are also

theoretical problems related to the construct of uncertainty avoidance. India has

often been described as a society in which contradictions exist and are not per-

ceived as contradictions (e.g. Sinha and Tripathi, 1994). Therefore, what uncer-

tainty means to an Indian might be quite different from what uncertainty means

to an American or a Brazilian (see Nisbett, et al. 2003, for a description of

differences in Western and Eastern thinking). An Indian worker, for example,

put a picture of Jesus next to her pictures of the Hindu Gods at her altar at home

(Güss, 2000). In many Western households, Christian and Hindu beliefs might

not fit together, and the person would choose either one of the two religious

worldviews.

The second theoretical problem is related to the two-item scale in this study.

It only refers to rule orientation and does not include the other two dimensions

of Hofstede, namely employment stability and stress. In our samples, Brazil

showed slightly less rule orientation than India and the United States. In Hof-

stede’s study (2001), assessing uncertainty avoidance with three items, Brazil

showed more uncertainty avoidance than India and the United States. Possible

reasons for these contradicting results are different samples, different times of

data gathering, and different uncertainty questions. Hofstede’s data are based on

IBM managers in the late 1960s and early 1970s, whereas our samples consist of

students who participated in 2003 and 2004. Although our questions were

derived from Hofstede’s questions, they focused only on rule orientation. His

questions referred to rule orientation, employment stability, and stress. A fur-

ther problem regarding the uncertainty scale in this study was the focus of the

questions on work and study context. The three samples differed significantly

regarding work experience and many students don’t have work experience, which

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 18 3/14/07 8:32:44 PM

C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25 19

could explain the low overall alpha coefficients. Further studies on uncertainty

avoidance in Brazil using a multi-method approach with different samples from

different parts of the country and from different professional backgrounds

would shed further light on these contradicting results.

It was hypothesized that uncertainty avoidance might influence frequency of

metacognitive strategies. This hypothesis was not confirmed due to the reasons

discussed above. Results show that low rule orientation correlated with facility

of several strategies and situations and with facility across all situations. Low rule

orientation also correlated significantly with step by step efficacy across all situa-

tions. Thus the less concerned participants were with certain rules, the easier to

implement certain strategies were perceived.

Another question investigated was whether or not metacognitive strategies

are situation-specific or more general cognitive styles. Regarding the cultural

samples, we expected the United States as an individualistic low-context culture

to show little variance across situations and we expected situational variability in

the Indian and Brazilian samples. The U.S. sample indeed showed no situational

differences, but, contradicting our hypothesis, the Brazilian and Indian partici-

pants also did not describe situation specific strategies. With the three different

problem domains – interpersonal, practical, and study – only one out of the five

strategies, the step by step strategy, varied across situations. It was most frequently

applied in study problems and least in interpersonal problems. This result might

be due to our samples which consisted of college students. For this sample, study

problems might be especially important and require a step by step approach.

Another possible explanation for the variation across situations in the step by

step approach could be related to the problem type. Study problems can be

defined more clearly than interpersonal and practical problems. In well-defined

problems, a step by step approach works better than in ill-defined problems.

Interpersonal and practical problems might be more uncertain thus not allowing

for a step by step approach.

Results indicate a tendency for metacognitive strategic preferences to hold

across situations in all countries, indicating a general metacognitive style rather

than a situation specific approach. However, the instrument did not give specific

interpersonal, practical, and study problems, which can be regarded as a strength

or as a weakness – as a strength, because participants can imagine relevant prob-

lems; as a weakness, because responses can differ according to the problems

imagined. We don’t know what specific problems participants imagined while

they were answering the questionnaire. It might be that the problem context

plays an important role for the selection of specific problem-solving strategies.

Further research investigating metacognitive strategies in more specific, concrete

situations is necessary before drawing conclusions. In a similar way, criticism that

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 19 3/14/07 8:32:44 PM

20 C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25

refers to survey data in general applies specifically to this survey. The chief con-

cern is whether or not ratings on such a questionnaire, where relatively abstract

strategies are imagined, reflect real problem-solving behavior. It would be inter-

esting to compare results from this metacognitive questionnaire with, for exam-

ple, thinking aloud protocols (Ericsson & Simon, 1980, 1984/1993) of concrete

problem-solving behavior in different situations. Strategic and metacognitive

preferences in these situations could then be compared with those indicated in

the questionnaire.

Results that might explain cross-cultural differences in metacognitive strate-

gies are the differences in abilities associated with each strategy in each country.

Out of eight abilities assessed for each of the five strategies, we find cross-cultural

differences in at least three of the eight abilities associated with each strategy.

Overall, Indian participants rated speed as more important than Brazilian and

U.S. participants in all five strategies. In the three strategies where significant

differences between cultural groups were found, Brazilians rated synthesis as

more important than Indian and U.S. participants, and U.S. participants rated

critical thinking as more important than Indian and Brazilian participants.

Apparently the individual skills required for specific metacognitive strategies

differ between cultures. Applying an eco-cultural framework (Berry, 2004),

skills are acquired in a specific cultural context. Those skills seem functional and

beneficial for success in a given environment. According to our respondents,

speed is a crucial factor in problem solving and decision making in India, synthe-

sis in Brazil, and critical thinking in the United States. It would be interesting to

investigate the differences in the cultural environment in these countries in more

detail in order to better understand the required individual skills. Regarding

Brazil, for example, Dessen & Torres (2002) highlight the economic instability

and many dynamic changes in the environment of many Latin American coun-

tries. In what way are the dynamic changes unique in Brazil and in what way do

they differ from those in India? And how does speed in one and synthesis in the

other culture respond to these changes?

Research about cultural preferences in problem-solving strategies is not only

relevant for cultural, cross-cultural, and cognitive psychology, but it is also rele-

vant for practical reasons. For instance, work-teams consisting of members from

different cultures might encounter difficulties in working together due to

different preferences in problem solving. Knowledge of these differences in

problem-solving strategies could lead to better mutual understanding and to

smoother work-relations.

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 20 3/14/07 8:32:45 PM

C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25 21

Acknowledgement

This study is part of a bigger project and based on work supported by the

National Science Foundation under Grant 0218203 to the first author from

2002 to 2006 with the title “Cultural influences on dynamic decision making.”

This research would not have been possible without the support of friends

and colleagues abroad. We would like to thank especially Prof. Cristina Ferreira,

Prof. Cilio Ziviani, Prof. Nadia, and Dr. Miguel Cal in Brazil; Prof. Krishna

Prasaad Sreedhar, Dr. S. Raju, Dr. Ajay Kesavan, and Mr. Ibrahim Syed in India,

and the many students who participated. We also would like to thank Paul Go

for his comments on an earlier version of this article.

Portions of the material were presented at the 25th Annual Convention of the

Society for Judgment and Decision Making in Minnesota, MN, November 2004.

References

Akama, K., & Yamauchi, H. (2004). Task performance and metacognitive experiences in problem-

solving. Psychological Reports, 94(2), 715-722.

Antonietti, A., Ignazi, S., & Perego, P. (2000). Metacognitive knowledge about problem-solving

methods. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 1-16.

Bartl, C., & Dörner, D. (1998). Sprachlos beim Denken – zum Einfluß von Sprache auf die Prob-

lemlöse- und Gedächtnisleistung bei der Bearbeitung eines nicht-sprachlichen Problems

[Speachless while thinking – on the influence of language on problem solving and memory per-

formance in a non-language problem]. Sprache & Kognition, 17(4), 224-238.

Beradi-Coletta, B., Buyer, L. S., Dominowski, R. L., & Rellinger, E. R. (1995). Metacognition and

problem solving: A process-oriented approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning,

Memory, & Cognition, 21(1), 205-223.

Berry, J. W. (2004). An ecocultural perspective on the development of competence. In R. J. Stern-

berg & E. L. Grigorenko (Eds.), Culture and competence (pp. 3-22). Washigton DC: American

Psychological Association.

Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Segall, M. H., & Dasen, P. R. (2002). Cross-cultural psychology.

Research and applications (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cooking, R. R. (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience,

and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Carlson, R. A. (1997). Experienced cognition. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Carr, M., & Borkowski, J. G. (1989). Kultur und die Entwicklung des Metakognitiven Systems

[Culture and the development of the metacognitive system]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psy-

chologie, 3(4), 219-228.

Carr, M., Kurtz, B. E., Schneider, W., Turner, L. A, & Borkowski, J. G. (1989). Strategy acquisition

and transfer among American and German children: Environmental influences on metacogni-

tive development. Developmental Psychology, 25(5), 765-771.

Chi, M. T. H., Bassok, M., Lewis, M. W., Reimann, P., & Glaser, R. (1989). Self-explanations. How

students study and use examples in learning to solve problems. Cognitive Science, 13, 145-182.

Davidson, G. R. (1994). Metacognition, cognition and learning. Old dubitations and new direc-

tions. South Pacific Journal of Psychology, 7, 18-31.

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 21 3/14/07 8:32:45 PM

22 C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25

Davidson, G. R., & Freebody, P. R. (1988). Cross-cultural perspectives on the development of

metacognitive thinking. Hiroshima Forum for Psychology, 13, 21-31

Dessen, M. A., & Torres, C. V. (2002). Family and socialization factors in Brazil: An overview. . In

W. J. Lonner, D. L. Dinnel, S. A. Hayes, & D. N. Sattler (Eds.), Online Readings in Psychology and

Culture (Unit 13, Chapter 2), (http://www.wwu.edu/~culture), Center for Cross-Cultural

Research, Western Washington University, Bellingham, Washington USA.

Dörner, D. (1996). The logic of failure. New York: Holt.

Dörner, D., Kreuzig, H. W., Reither, F., & Stäudel, T. (1983). Lohhausen. Vom Umgang mit

Unbestimmtheit und Komplexität. [Lohhausen. Dealing with Uncertainty and Complexity].

Bern, Switzerland: Huber.

Duncker, K. (1945). On problem solving. Psychological Monographs, 58(5). Whole No. 270.

Dunlosky, J. (1998). Epilogue: Linking metacognitive theory to education. In D. J. Hacker,

J. Dunlosky, & A. Graesser (Eds.), Metacognition in educational theory and practice (pp. 367-

381). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1980). Verbal reports as data. Psychological Review, 87(3), 215-251.

Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1984/1993). Protocol analysis: Verbal reports as data. Cambridge:

MIT Press.

Fischer, R. (2004). Standardization to account for cross-cultural response bias: A classification of

score adjustment procedures and review of research in JCCP. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychol-

ogy, 35(3), 263-282.

Flavell, J. (Ed.) (1976). Metacognitive aspects of problem solving. The nature of intelligence. Hillsdale,

NJ: Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Fleith, D. S. (2002). Creativity in the Brazilian culture. In W. J. Lonner, D. L. Dinnel, S. A. Hayes,

& D. N. Sattler (Eds.), Online Readings in Psychology and Culture (Unit 5, Chapter 3), (http://

www.wwu.edu/~culture), Center for Cross-Cultural Research, Western Washington University,

Bellingham, Washington USA.

Glaser, R., & Chi, M. T. H. (1988). Overview. In M. T. H. Chi, R. Glaser, & M. J. Farr (Eds.), The

nature of expertise (pp. XV-XXXVI). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Glencross, E., & Güss, C. D. (2004, November). Indian fatalism? American pragmatism? Culture,

values, and planning. Poster presentation at the 25th Annual Convention of the Society for Judg-

ment and Decision Making to be held in Minnesota, MN, November 19 to 22, 2004.

Gross, N. (2002). Becoming a pragmatist philosopher: Status, self-concept, and intellectual choice.

American Sociological Review, 67(1), 52-76.

Güss, D. (2000). Planen und Kultur? [Planning and culture?]. Lengerich, Germany: Pabst.

——. (2002). Decision Making in Individualistic and Collectivist Cultures. In W. J. Lonner,

D. L. Dinnel, S. A. Hayes, & D. N. Sattler (Eds.), OnLine Readings in Psychology and Culture,

Western Washington University, Department of Psychology, Center for Cross-Cultural

Research. Web site: http://www.wwu.edu/~culture

Güss, C. D., Glencross, E., Tuason, M.T., Summerlin, L., & Richard, F. D. (2004). Task complexity

and difficulty in two computer-simulated problems: Cross-cultural similarities and differences.

In K. Forbus, D. Gentner, & T. Regier (Eds.), Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Annual Conference

of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 511-516). Mahwah, NJ: Cognitive Science Society and Law-

rence Erlbaum Associates.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. New York: Doubleday.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1993). Human and machine thinking. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Kluckhohn, C., & Murray, H. A. (1953). Personality formation: The determinants. In C. Kluck-

hohn & H. A. Murray (Eds.), Personality in nature, society, and culture (2nd edition, revised and

enlarged) (pp. 53-67). New York: Knopf.

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 22 3/14/07 8:32:45 PM

C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25 23

Kroeber, A. A., & Kluckhohn, C. (1963). Culture. A critical review of concepts and definitions. New

York: Vintage Books.

Land, S. (2004). A conceptual framework for scaffolding ill-structured problem-solving processes

using question prompts and peer interactions. Educational Technology, 52, 5-22.

Lauth, G. (1996). Effizienz eines metakognitiv-strategischen Trainings bei lern- und aufmerksam-

keitsbeeinträchtigten Grundschülern. [The effectiveness of a metacognitive strategies training

program among children with learning and attention disorders.] Zeitschrift für Klinische Psy-

chologie. Forschung und Praxis, 25(1), 21-32.

Lin, X. (2001). Designing metacognitive activities. Educational Technology, 49, 28-40.

Mann, L., Radford, M., Burnett, P., Ford, S., Bond, M., Leung, K., Nakamura, H., Vaughan, G., &

Yang, K.-S. (1998). Cross-cultural differences in self-reported decision-making style and

confidence. International Journal of Psychology, 33(5), 325-335.

McCafferty, S. G. (1992). The use of private speech by adult second language learners: A cross-

cultural study. Modern Language Journal, 76(2), 179-189.

Mevarech, Z., & Kramarski, B. (2003). The effects of metacognitive training versus worked-out

examples on students’ mathematical reasoning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 73, 449-471.

Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I, & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holis-

tic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108(2), 291-310.

Ohbushi, K.-I., Fukushima, O., & Tedeschi, J. T. (1999). Cultural values in conflict management:

Goal orientation, goal attainment, and tactical decision. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30,

51-71.

Pajares, F. (2003). William James: Our father who begat us. In B. J. Zimmerman (Ed.), Educational

psychology: A century of contributions (pp. 41-64). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Perry, D. K. (Ed.) (2001). American pragmatism and communication research. Mahwah, NJ: Law-

rence Erlbaum Associates.

Rohlfing, K. J., Rehm, M., & Goecke, K. U. (2003). Situatedness: The interplay between context(s)

and situation. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 3(2), 132-156.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. New York: Free Press.

Saxe, G. B. (1994). Studying cognitive development in sociocultural context: The development of

a practice-based approach. Mind, Culture, & Activity, 1(3), 135-157.

Scheper-Hughes, N. (1990). Mother love and child death in Northeast Brazil. In J. W. Stigler,

R. A. Shweder & G. Herdt (Eds.), Cultural Psychology. Essays on comparative human development

(pp. 542-565). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schmidt, A., & Ford, J. (2003). Learning within a learner control training environment: The inter-

active effects of goal orientation and metacognition instruction on learning outcomes. Personnel

Psychology, 56, 405-419.

Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Beyond individualism/collectivism. New cultural dimensions of values. In

U. Kim, H. C. Triandis, Ç. Kâgitçibasi, S.-C. Choi, & G. Yoon (Eds.), Individualism and collec-

tivism. Theory, method, and applications (pp. 85-119). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Simonton, D. K. (1984). Genius, creativity, and leadership. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sinha, D., & Tripathi, R. C. (1994). Individualism in a collectivist culture. A case of coexistence of

opposites. In U. Kim, H. C. Triandis, Ç. Kâgitçibasi, S.- C. Choi, & G. Yoon (Eds.), Individual-

ism and collectivism. Theory, method, and applications (pp. 123-136). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Smith, P. B., & Bond, M. H. (1998). Social psychology across cultures (2nd ed.). London: Prentice

Hall.

Smith, P. B., Peterson, M. F., & Schwartz, S. H. (2002). Cultural values, sources of guidance, and

their relevance to managerial behavior. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 33(2), 188-208.

Spranzi, M. (2004). Galileo and the mountains of the moon: Analogical reasoning, models and

metaphors in scientific discovery. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 4(3), 451-483.

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 23 3/14/07 8:32:45 PM

24 C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25

Stubbe, H. (1987). Geschichte der Psychologie in Brasilien. Von den indianischen und afro-brasilianischen

Kulturen bis in die Gegenwart [History of psychology in Brazil. From Indian and Afro-Brazilian

cultures to the present]. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer.

Tisdale, T. (1998). Selbstreflexion, Bewußtsein und Handlungsregulation. [Selfreflection, conscious-

ness, and action regulation.] Weinheim: Beltz.

Sternberg, R. J. (2003). Cognitive psychology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson.

Strohschneider, S., & Güss, D. (1998). Planning and problem solving: Differences between Brazil-

ian and German students. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29(6), 695-716.

van de Vijver, F., & Leung, K. (1997). Methods and data analysis of comparative research. In J. W.

Berry, Y. H. Poortinga, & J. Pandey (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology. Volume 1:

Theory and method (pp. 257-300). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Veenman, M., Wilhelm, P., & Beishuizen, J. (2004). The relation between intellectual and metacog-

nitive skills from a developmental perspective. Learning and Construction, 14, 89-109.

Vosniadou, S., & Ortony, A. (Eds.) (1989). Similarity and analogical reasoning. Cambridge: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Weber, E. U., & Hsee, C. K. (2000). Culture and individual judgment and decision making. Applied

Psychology: An International Review, 49(1), 32-61.

Wertheimer, M. (1959). Productive thinking. New York: Harper.

Appendix A

Uncertainty avoidance questions

1. Company rules should not be broken – even when the employee thinks it is in the company’s

best interests.

strongly agree 1—2—3—4—5 strongly disagree.

2. University rules should not be broken – even when the student thinks it is in the university’s

best interests.

strongly agree 1—2—3—4—5 strongly disagree.

3. How often do you feel nervous or tense in class?

I always feel this way. 1—2—3—4—5 I never feel this way.

If you work, answer questions 4 and 5a. If not, go to question 5b

4. How often do you feel nervous or tense at work?

I always feel this way. 1—2—3—4—5 I never feel this way.

5a. How long do you think you will continue working for this company?

a) one year at the most

b) from 1 to 2 years

c) from 3 to 5 years

d) more than five years

e) until I retire

If you do not work

5b. How long would you like to work in a company?

a) one year at the most

b) from 1 to 2 years

c) from 3 to 5 years

d) more than five years

e) until I retire

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 24 3/14/07 8:32:46 PM

C. D. Güss, B. Wiley / Journal of Cognition and Culture 7 (2007) 1-25 25

Appendix B*

I try to recall problems successfully solved in the past which are similar to the current problem. I

look for previous situations which share some aspects, elements or features with the current

problem so that I can transfer some ideas from the former ones to the latter one. 1 stands for very

little and 5 stands for very much.

Think of the application of this strategy to interpersonal problems:

*how frequently I apply this strategy 1 2 3 4 5

*how useful I think this strategy is 1 2 3 4 5

*how easy I think this strategy is to apply 1 2 3 4 5

Think of the application of this strategy to practical problems:

*how frequently I apply this strategy 1 2 3 4 5

*how useful I think this strategy is 1 2 3 4 5

*how easy I think this strategy is to apply 1 2 3 4 5

Think of the application of this strategy to study problems:

*how frequently I apply this strategy 1 2 3 4 5

*how useful I think this strategy is 1 2 3 4 5

*how easy I think this strategy is to apply 1 2 3 4 5

Which of the following mental abilities do you think are involved when the strategy is applied?

[ ] creativity [ ] speed [ ] synthesis [ ] critical thinking

[ ] accuracy [ ] memory [ ] analysis [ ] logical reasoning

* Reproduced with permission from The British Journal of Educational Psychology, (c) The British Psycho-

logical Society

JOCC 7,1-2_f2_1-25.indd 25 3/14/07 8:32:46 PM

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- tmpF178 TMPDocument15 paginitmpF178 TMPFrontiersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tmp1a96 TMPDocument80 paginiTmp1a96 TMPFrontiersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tmpa077 TMPDocument15 paginiTmpa077 TMPFrontiersÎncă nu există evaluări

- tmpE3C0 TMPDocument17 paginitmpE3C0 TMPFrontiersÎncă nu există evaluări

- tmp998 TMPDocument9 paginitmp998 TMPFrontiersÎncă nu există evaluări

- tmp3656 TMPDocument14 paginitmp3656 TMPFrontiersÎncă nu există evaluări

- tmp27C1 TMPDocument5 paginitmp27C1 TMPFrontiersÎncă nu există evaluări

- tmpA7D0 TMPDocument9 paginitmpA7D0 TMPFrontiersÎncă nu există evaluări

- tmp96F2 TMPDocument4 paginitmp96F2 TMPFrontiersÎncă nu există evaluări

- tmp97C8 TMPDocument9 paginitmp97C8 TMPFrontiersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Assignment 2Document8 paginiAssignment 2Yana AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 Experimental Variables-S PDFDocument5 pagini3 Experimental Variables-S PDFDonna NÎncă nu există evaluări

- SS E LA PT Homogeneity and StabilityDocument12 paginiSS E LA PT Homogeneity and Stabilitysugeng raharjoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wilhelm Dilthey, Introduction To The Human SciencesDocument8 paginiWilhelm Dilthey, Introduction To The Human SciencesAlla Tofan50% (2)

- Executive Master: École PolytechniqueDocument20 paginiExecutive Master: École PolytechniqueFNÎncă nu există evaluări

- Form Th-1 National University of Sciences & Technology Master'S Thesis Work Formulation of Guidance and Examination CommitteeDocument3 paginiForm Th-1 National University of Sciences & Technology Master'S Thesis Work Formulation of Guidance and Examination CommitteeBibarg KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1-S2.0-S0950705122010255-Main KamboucheDocument11 pagini1-S2.0-S0950705122010255-Main KamboucheSonia SarahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lie Behind The Lie Detector - Maschke, George W & Scalabrini Gino JDocument128 paginiLie Behind The Lie Detector - Maschke, George W & Scalabrini Gino Jieatlinux100% (1)

- Daftar PustakaDocument3 paginiDaftar PustakaDwi LestariÎncă nu există evaluări

- ORA-LAB.5.5 Equipment v02Document19 paginiORA-LAB.5.5 Equipment v02Fredrick OtienoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Immaterial Bodies: Affect, Embodiment, MediationDocument28 paginiImmaterial Bodies: Affect, Embodiment, MediationelveswillcomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 1-FMS - Week - 11Document23 paginiGroup 1-FMS - Week - 11RameshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statistical Significance - WikipediaDocument43 paginiStatistical Significance - WikipediaFadzil Adly IshakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Visual MethodologiesDocument4 paginiVisual MethodologiesYudi SiswantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Atomic Structure: Rutherford Atomic Model, Planck's Quantum Theory, Bohr Atomic Model, de Broglie Dual Nature, Heisenberg's Uncertainty PrincipleDocument15 paginiAtomic Structure: Rutherford Atomic Model, Planck's Quantum Theory, Bohr Atomic Model, de Broglie Dual Nature, Heisenberg's Uncertainty PrincipleBedojyoti BarmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Early Ideas About AtomsDocument3 paginiEarly Ideas About AtomsJennylyn Alumbro DiazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advanced Anthropology SyllabusDocument7 paginiAdvanced Anthropology SyllabusLucille Gacutan AramburoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geographical Research On Tourism, Recreation and Leisure: Origins, Eras and DirectionsDocument20 paginiGeographical Research On Tourism, Recreation and Leisure: Origins, Eras and Directionsitamar_cordeiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Date Sheet Igcse Oct/Nov 2021: Code Subjects Component Title Date DAY Session DurationDocument2 paginiDate Sheet Igcse Oct/Nov 2021: Code Subjects Component Title Date DAY Session Durationwaqas481Încă nu există evaluări