Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

AGOA Beyond: An Updated Case For A Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership Between Africa and The U.S.

Încărcat de

The Wilson CenterTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

AGOA Beyond: An Updated Case For A Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership Between Africa and The U.S.

Încărcat de

The Wilson CenterDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Steve MCDONALD . Stephen LANDE .

Dennis MATANDA

Washington, DC, April 2013

AGOA

BEYOND

AN UPDATED CASE

FOR A TRANS - ATLANTIC

TRADE & INVESTMENT PARTNERSHIP

BETWEEN AFRICA & THE UNITED STATES

a Wilson Center & Manchester Trade collaboration

Steve McDonald

Stephen Lande

Dennis Matanda

Steve is Director of the Africa Program at the Wilson Center

in Washington, DC. A former Foreign Service Ofcer,* he

has traveled extensively to the region and the world, is widely

published, has taught at various universities and has also

lived in parts of West, Central and Southern Africa.

With a 50-year career in trade policy at State Department,

at the USTR and in the private sector, Stephen was pivotal to

adding bilateral and plurilateral elements to U.S. trade policy

that had almost exclusively been multilateral and based on the

GATT.

1

He was key to initiatives such as AGOA, CBI

2

and GSP

3

as well as various US FTAs.

4

He is President of Manchester Trade

and also an adjunct professor at the Paul H. Nitze School of

Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University.

A profcient government relations specialist, Dennis is a post

graduate scholar of American Politics and Government from

Uganda. He serves as editor of Te Habari Network, an online

Diaspora paper, and is currently working on his second book,

Master of the Sagging Cheeks, a work of political fction.

* Uganda and South Africa; and as Desk Ofcer for Angola, Mozambique,

Cape Verde, Guinea Bissau, Sao Tome & Principe

1. General Agreement on Tarifs and Trade 2. Caribbean Basin Initiative

3. Generalized System of Preferences 4. Israel, Mexico and Canada, in Central America and with the Dominican Republic

* Dennis headed Ugandas Gifed by Nature campaign and was one of three founding

members of the Uganda Media Center

Design by Afrolehar . Washington, DC . www.afrolehar.com

AGOA ~ Africa Growth Opportunities Act

AU - African Union

BITS ~ Bilateral Investment Treaties

COMESA ~ Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa

CCA ~ Corporate Council on Africa

DBIA ~ Doing Business in Africa

EAC ~ East African Community

EBA ~ Everything But Arms

ECOWAS ~ Economic Community of West African States

EPA ~ Economic Partnership Agreement

EU ~ European Union

EXIM Bank ~ Export Import Bank

FDI ~ Foreign Direct Investment

FOCAC ~ Forum on China Africa Cooperation

FTA ~ Free Trade Area | Free Trade Agreement

ICT ~ Information Communication Technology

IPR ~ Intellectual Property Rights

MBDA ~ Minority Business Development Agency

MCC ~ Millennium Challenge Corporation

MNC ~ Multinational Corporation

NGO ~ Non Governmental Organization

NSC ~ National Security Council

NSS ~ National Security Staff

OPIC ~ Overseas Private Investment Corporation

RECs ~ Regional Economic Communities

SADC ~ Southern Africa Development Community

SBA ~ Small Business Administration

SMEs ~ Small Medium Enterprises

SPVs ~ Special Purpose Vehicles

SSA ~ Sub - Saharan Africa

TIFA~Trade and Investment Framework Agreement

TRQs ~ Tariff Rate Quotas

USAID ~ United States Agency for International Development

USTDA ~ United States Trade and Development Agency

USTR ~ United States Trade Representative

WTO ~ World Trade Organization

Abbrevi ati ons

Preamble

In this paper, McDonald, Lande & Matanda argue that, premised on

conditions here in the U.S., in Africa and elsewhere, the perfect storm

could be brewing for an effective renewal or enhancement of AGOA

before the program expires in 2015.

With ingredients such as the Obama Administrations whole-of-gov-

ernment approach, Africas rapid ascent as a trade and investment

destination and the risk of an inappropriate response to China and

other third countries Africa engagement, the papers recommenda-

tions pivot towards ensuring that the U.S. and Africa form a more

equitable commercial partnership.

An Introduction

Three months into the Obama Second Term -

amidst a flurry of activity on the U.S. | Africa

trade and investment policy front - our col-

leagues at the Heritage Foundation, Brookings

Institution, Corporate Council on Africa, and the

Wilson Center, amongst others argue that theres

apparent continuity rather than change in U.S.

policy

1

towards Africa; they suggest that the U.S.

has been slow to seize the opportunities availed

by the new Africa;

2

and also warn that without a

much better focused effort, the U.S. may lose the

chance to play a substantial role (in) developing a

region of major importance.

3

In this paper, we agree with the collective ratio-

nale that there are gaps in U.S. policy towards Af-

rica, and we also make the case for an even more

ambitious transatlantic partnership between sub

Saharan Africa and the U.S. Fortunately start-

ing last year, both the U.S. Administration and

Congress recognized the need for more intensive

American engagement with sub Saharan Africa.

In June 2012, Michael Froman, both a Special

Assistant to the President and the Deputy Na-

tional Security Advisor for International Eco-

nomic Affairs unveiled the Presidential Directive

on Sub Saharan Africa at the 12th AGOA Forum

in Washington DC and laid the foundation for

a new program by emphasizing the whole-of-gov-

ernment approach. Congress seemingly awoke as

well with a number of their own Africa-centric

initiatives.

There were 3 significant congressional actions:

The first was a commitment earlier this year by

the House Ways and Means Committee to extend

and possibly enhance AGOA on a timely basis,

meaning that something should be done before

the 114th Session of Congress commences in

January 2015. With this same deadline in mind,

Karen Bass (D-CA), ranking member of the

House Subcommittee on Africa, has engaged and

formed a working group of influential members

to review options for AGOA renewal.

Finally, a comprehensive bill was introduced by

a bipartisan group of Senators and Congressmen

led by Senator Dick Durbin, the powerful Senate

Majority Whip from Illinois and by Rep. Chris

Smith (R-N.J.), Chairman of the House Sub-

committee on Africa, Global Health and Human

Rights. Entitled The Increasing American Jobs

through Greater Exports to Africa Act, this bill

set out to do exactly as its name suggested. It was

meant to effectively level the playing field for U.S.

exporters against the Chinese in Africa by pro-

moting US investment and creating jobs both in

Africa and the U.S. Seminally, while each of these

actions is under the jurisdiction of separate enti-

ties, they are also indicative of like-minded units

that could be coordinated to ensure a coherent

federal government approach.

Thus, we suggest specific steps that can be im-

plemented by the Administration and Congress

to achieve an ambitious bipartisan transatlantic

partnership between the U.S. and Africa. Arms of

government must start by incorporating AGOA

in a legislative endeavor that ultimately supports

an expanded U.S. commercial presence in Africa.

As Africa prospers, the U.S. must pivot away from

humanitarian programs. African governments

are increasingly better placed to take care of their

own people which, on its own, creates the foun-

dation for a perfect storm for business in Africa

since the U.S. can shift precious resources to-

wards economic development activity.

Thus, a gentle nudge from the Obama admin-

istration could be the tipping point that alters

Americas waning fortunes in Africa.

____________________________________________

1. From An Assessment of the Obama Administrations Africa Strategy,

hosted by Ray Walser, Ph.D. Senior Policy Analyst, the Heritage Foundation,

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

2. From Top Five Reasons Why Africa Should Be a Priority for the United

States, by John P. Banks, et al, Africa Growth Initiative, Brookings, Mar. 2013

3. From Policy Recommendations on Africa for the Second Obama Adminis-

tration, by the Corporate Council on Africa, April 17, 2013.

i

Since 2009, the U.S. is no longer Africas single biggest trade partner or its most

important source of investment.

I ntroducti on

Executive Summary

Ever since the beginning of 2013, the Economist

has, ostensibly, half-dared and half tantalized U.S. in-

vestors to dip their toes in the rich, warm water that

is Africa. Almost all the papers weekly issues have

carried a glorious story about the potential that is in

Africa: and yet the U.S., unlike China, and smaller

economies, still does not respond appropriately to

the call of the wild wealth of todays new world.

Te Economist and other reputable houses, includ-

ing the infuential McKinsey all say the same thing:

Six of the worlds fastest growing economies are in

Africa, and the next decade portends even more for

what many once referred to as the dark continent.

Now called the hottest frontier, Africa has oppor-

tunities unavailable in the richer world. On top of

a rapidly expanding consumer middle class on the

continent, there are abundant natural resources, hu-

man energy, youth, aspirations and a willingness to

work - exactly the ingredients everyone aside from

America is leveraging so as to rush their share of for-

eign direct investment and resources to secure the

lucrative ventures waiting to be plucked.

But the worlds largest economy is, ostensibly, much

too largesse to be lithe. While the U.S. dithers, China,

the second largest economy, methodically works to

expand its economic presence on the continent. Te

EU is also aggressively using trade negotiating tac-

tics to secure a special position in the region. Com-

bined with aggressive action by India, Brazil and a

slew of smaller economies, American exporters and

entrepreneurs are, increasingly, at a disadvantage in

Africa unless remedial actions are undertaken.

Te Obama Administration has already begun to

coordinate resources of agencies working in Africa.

In their aforementioned whole-of-government ap-

proach, the State and Commerce departments are

in better tandem with the U.S. Trade Representa-

tives Ofce as well as a whole alphabet of entities

- ExIm Bank, MBDA, MCC, OPIC, SBA, and UST-

DA, amongst others. All collaborate with the pri-

vate sector to tackle African afairs. However, more

still needs to be done in concert with Congress to

produce a truly sustainable US footprint in Africa.

Without timely intervention, Americans are not

competitive in Africas burgeoning capital and con-

sumer goods industry, in their infrastructure and

service sectors, and not even in the continents beck-

oning agriculture or information technology felds.

Enhancing AGOA

Remarkably, in spite of a plethora of crises,* this

may be just the conducive environment for the

U.S. to craft a more expansive program and eco-

nomic initiative for Africa - an enhanced AGOA.

Instructively, as Americas most significant Africa

program, AGOA does, indeed, present a baseline

for a more equitably beneficial partnership.

Hence, alongside the Transatlantic Partnership

with the European Union and the Trans Pacific

Partnership, Obama could achieve the kind of

comprehensive program for Africa many, both in

Africa and the U.S. hoped for at the start of his

novel presidency.

However, before legislative action on an initia-

tive of this potential can be commenced, we must

acknowledge that AGOA has been inadequate in

transforming Africas sectors into equitable part-

ners of global supply chains and distribution net-

works. This possibly, was because AGOA came

at a time when, except for a handful of economic

success stories, Africas development lagged be-

hind the rest of the world.

But the U.S. must not live in the past. Today, only

13 years into the new century, entrepreneurs from

Brisbane to Sao Paulo, Seoul and in between reap

super normal profits from their Africa ventures.

And in overly relying on the inadequate trade pro-

visions in AGOA, the U.S. loses strategic ground

each day to third countries.

From this standpoint, those advocating simple

continuity of AGOA or pushing for small ball re-

form independent of the bigger picture may actu-

ally be the greatest threat to a more progressive

U.S. - Africa program - even more dangerous to

American progress than traditional protectionist

and isolationist views.

ii

Executi ve Summar y

* Te expiration of the Bush Tax Cuts, the Sequestration and the looming Debt

Ceiling negotiations, plus a furry of legislative activity.

Anyone suggesting a simple rollover of AGOA

ought to look beyond the status quo to see that

this does not scratch the surface of what can be

achieved in Africa. To their credit, the big Ameri-

can boys Coca Cola, Microsoft, Walmart, GE,

Procter & Gamble, amongst others continue to

fly the American flag in the region. But Witney

Schneidman in a recent Brookings publication ar-

gues that these represent only 1% of U.S. FDI, and

U.S. exports to Africa are just over $ 22 billion -

about only 2% of worldwide exports. Besides, the

big boys do not necessarily need AGOA!

Time is of the essence: AGOA expires in 2015. Be-

cause we mustnt wait for the 114th Congress to

sit in January 2015, collaboration between Obama

and the 113th Congress on a well coordinated ap-

proach to stave off Chinas influence and EU pref-

erences in Africa must start soon. We recommend

that the next 18 months not only be used to renew

and enhance AGOA but ensure that the renewal is

part of an overall US approach towards the region.

Potential Ingredients to Effective Policy

1. American stakeholders must agree that collec-

tivity is better than unilateralism, and all arms of

government and private sector must collaborate

in a public - private partnership to garner the kind

of legislation that will change the current down-

ward trajectory of Americas business in Africa.

Here, Americas humanitarian, national security

and economic interests are much better served by

agencies and private sector leveraging potential

coordination.

Brookings suggests that the U.S. must build sustainable health systems

that reduce the need for large international responses to disaster;

leverage assistance programs to stimulate economic growth and

governance in Africa. Likewise, any new plan should continue to

require that agencies with African components work closely with the

MBDA and SBA to promote African American, Diaspora investment

and SME business activities with specific targets such as doubling U.S.

exports to Africa within set periods of time.

2. We applaud Congress effort towards doubling

US exports: In a recent article, Delaware Senator

Chris Coons, Africa Subcommittee Chair of the

influential Senate Foreign Relations Committee,

called for more commercial officers to be sent

to Africa - including those from ExIm Bank and

OPIC. However, this by itself, will do little to offset

the billions of dollars being spent by the Chinese

Government to support that countrys expanding

commercial presence in the region.

US commercial goals require that US increase

support to African efforts to remove barriers to

the free flow of products and factors of produc-

tion within the region. Fortunately such assistance

is not that expensive and can be achieved through

reprogramming existing programs as well as by

adopting the smarter use of scarce resources.

For instance, the U.S. should establish special

purpose vehicles to support US participation in

regional infrastructure beyond specific borders.

In addition, one could utilize a revised MCC

through requiring that 20% of compact resource

be allocated for projects contributing to regional

integration.

Concurrently, while an initiative must encourage

creative financial instruments that benefit Amer-

ican firms in Africa, vital proposals such as the

Boozman, Coons, Durbin, Rush + Smith congres-

sional proposal to target $10 billion a year of the

recent $40 billion increase in ExIm lending abil-

ity to Africa should conform to projected business

suggestions and represent off budget activities not

impacted by sequestration.

Amongst their recommendations to the Second Term Obama Admin-

istration, the Corporate Council on Africa suggests that a target be

set at presidential level for $ 10 billion in funding for infrastructure

projects, agriculture, health, ICT, energy and heavy machinery.

The Council also recommends that a U.S. Trade Development Au-

thority evergreen fund support African feasibility studies to be used

by the African Development Bank or World Bank.

3. The U.S. must not accept the status quo or be

too cautious to tackle the big issues because of

concern over partisan rancor in Congress. Be-

sides, policy on U.S. - Africa trade relations is

one of the few areas where bipartisan agreement

between Republicans and Democrats is still alive

and thriving.

iii

I ngredi ents

With Obama freed from having to prove heritage, a more open and

aggressive commercial policy towards the region can now be imple-

mented. Besides, Republicans who still control the House realize that

their best hope to increase votes may lie in championing as many pro-

minority programs. A pro-Africa program could mean addition to the

more than 100,000 AGOA created American jobs.

4. The U.S. must not be blinded by a desire to ne-

gotiate closer relations with Europe under the

Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership

(T-TIP). The EU policies that force African coun-

tries to provide preferential access for European

exports in sub Saharan markets pose a clear and

present danger to U.S. commercial interests and

also, the survival of AGOA in its present form.

Illustrative Initiatives

A solid body of ideas and proposals for an en-

hanced U.S. - Africa economic partnership exists.

Like already mentioned, various parties, includ-

ing Corporate Council on Africa as well as con-

tinuous work by Brookings, Heritage and this col-

laboration between Wilson Center and Manchester

Trade are in the process of putting suggestions up

for discussion.

Secondly, the current Washington trade agenda

is not crowded. With the exception of possibly

considering renewal of Trade Promotion Author-

ity (TPA) - something that could take months of

consultations before a bill is presented - these are

ideal conditions for crafting of successful U.S.-

Africa legislation.

The WTOs DOHA Round is, at best, moribund;

the Transatlantic Trade + Investment Partnership

yet to be launched, and even the optimistic dont

expect TPP negotiation to conclude before the end

of 2013 at the earliest, meaning that any agree-

ment resulting from these negotiations will not be

presented to congressional committees until mid

2014. This should allow time for the respective

committees to complete work on a transatlantic

initiative on Africa.

Whatever the case, a new U.S. - Africa program

must be put through Congress rigorous legisla-

tive process. Also, considering that the basic ar-

chitecture of AGOA was developed in the last

century, renewing or tweaking aspects of it does

not do justice to recent latent synergy between the

worlds largest economy and a region thats grow-

ing at a pace much faster than fathomable less

than 10 years ago.

Thus, our three supra-AGOA proposals are geared

towards adjusting existing programs to have a

greater commercial impact with a view to sup-

porting regional integration and also U.S. invest-

ment in Africa.

Proposal 1: Adjustment to Existing Programs

i. The new legislation should, first and foremost,

address oft repeated but still pertinent propos-

als on agricultural products by adding currently

excluded exports subject to tariff rate quotas to

AGOA eligibility. This step could double the value

incorporated in non-petroleum imports entering

the US under the program.

Also, all AGOA provisions, including those ap-

plicable to textiles, should be extended for a long

enough period - at least ten years - to avoid the

uncertainty caused by the short term extensions

in the past.

ii. AGOA should become part of an overall Con-

gressional approach. Since these bills oftentimes

originate in the House, they should be coordi-

nated by either the House leadership or by a joint

working group of Chairmen and Ranking Mem-

bers of the Foreign Affairs, Ways & Means, Fi-

nancial Services & Commerce committees or ap-

propriate subcommittees. Here, AGOA should be

stand-alone legislation and part of an overall ap-

proach fully coordinated with other stand-alone

legislation passed out of different committees.

Additional bills could also cover programs under

ExIm, MCC, OPIC, TDA + USAID among others

with a focus on creating a level playing field for

American businesses, promoting their participa-

tion in the development of regional infrastructure

and in Africas productive capacity.

I ni ti ati ves + Proposal s

iv

iii. Relatively, all programs must re-enforce each

other: For instance, MCC and USAID investments

in Africa should be linked, wherever possible, to

loans from ExIm Bank, OPIC and USTDA.

iv. Because Congress does not treat failure kindly,

federal agencies may be justified in their precau-

tion. However, being much too process and pro-

cedure driven goes against the grain of economic

activity, and the meme that U.S. programs have

onerous conditionality must be dealt with im-

mediately or continue the risk of being further

shunned by the private sector. The premise here

would be a whole-of-government approach that al-

lows for the inevitability of venture failure.

v. Given the fact that Africa is still divided into

48 separate countries, the continent must work

out its own trade policy in the context of integra-

tion efforts. Thus, the U.S. must temper her trade

priorities, at least, in the short term. To this, the

U.S. Trade Representative must modify or delay a

natural proclivity to gain reciprocity from African

countries in the tariff area, ensuring that AGOA

is renewed or enhanced with the programs non-

reciprocal status.

Nonetheless, the US should continue efforts to

support American investors through such mea-

sures as liberalizing non-tariff measures, improv-

ing protection of Intellectual Property Rights

(IPRs) and entering into Bilateral Investment

Treaties (BITs).

Striving to strengthen its relationship with the

East African Community, the US is working on a

regional Trade and Investment Framework Agree-

ment (TIFA). This sort of relationship intensifi-

cation and effort to improve regional integration

conditions should be extended to other African

RECs. The expectation should be that the African

Union and RECs will use this extended AGOA pe-

riod to progress towards a continental FTA + CET

by the end of the decade.

We address this in Proposal 2.

vi. These changes to current programs should also

address the important issue of sanctions and con-

ditionality. No matter how laudable, theres little

impact on strengthening democratic practices in

an African country through unilateral withdrawal

of AGOA benefits or a cessation of MCC or US-

AID development programs.

Instead, whenever a country is suspended or se-

questered, US firms lose business to countries like

China which simply supplant American firms,

further undermining the AGOAs positive intent -

even weakening the very groups that may oppose

heavy handed regimes.

The deleterious effect of suspending programs

with long run development outcomes beyond the

restoration of democracy can be avoided by tar-

geted sanctions. Interpretively, ICJ proceedings,

arms embargoes, travel restrictions and freezing

of assets would be imposed on dictators, their

henchmen and their families.

Following a military coup in Madagascar, the U.S. took unilateral

action in removing that countrys AGOA eligibility. However, this very

action not only affected the economy, but especially the Malagasy

women producing under AGOA.

In a parallel illustration, American businesses in the Democratic

Republic of Congo lost vantage points to Chinese investment when the

country was removed from those benefitting from AGOA. While this

sanction was meant to end barbarous practices used by both sides in

that countrys civil war, Americas reaction had no discernible impact

- except to cause a direct hit to U.S. investors.

We recommend that automatic + unilateral sus-

pension of benefits be replaced with a collective

approach. For example, peer pressure by one or

more African countries on dictatorial neighbors

has been effective in helping West African lead-

ers be more democratically conscious.

vii. Given present technology, Africa should re-

main reliant on fossil fuels for many years. Thus,

while we support special incentives to promote

the use of clean energy, the US must lift prohibi-

tions on supporting fossil fuel development when

cleaner forms of energy are not feasible or com-

petitive.

Proposal s

v

Proposal 2: Regional Integration

To help Africa achieve a more sustainable path to

development, the U.S. must make the support of

regional integration a much higher priority than

currently is the case. Theres no question that if

Africa is to reach middle income status in the

foreseeable future, it must be integrated into the

supply chains and distribution networks which

increasingly dominate international trade.

Sub Saharan African countries are at the stage

where an enduring partnership is necessary for

their emergence. The economies of almost all of

the 48 countries into which Africa is subdivided

are too small to effectively participate in world-

class supply chains and distribution networks.

Thus U.S. multinational firms can only optimally

operate in Africa if borders do not hinder the free

flow of goods. Effective regional integration is,

undoubtedly key for big business.

With this in mind, we suggest the following:

i. Tat the U.S. use the bucket of global issues under

the impending negotiations for a Transatlantic Trade

and Investment Project (T-TIP) to develop consen-

sus on issues of mutual concern with the EU.

Te two powerful economic entities should develop

a joint approach towards reciprocity from the region:

Te U.S. should renew AGOA in its present non-re-

ciprocal form until 2025, and the EU should delay

its negotiations of economic partnership agreements

(EPAs) until the next decade as well.

Tis would not only allow Africa sufcient time to

complete negotiations for a continental FTA and

CET but once in place would allow Africa the bene-

fts of negotiating as a group - including eliminating

the obstacles to regional integration posed by tarif

commitments undertaken by some but not all sub

Saharan African countries under EPAs.

If the EU persists in its current efforts to conclude such agreements

with the more advanced countries in the region (non- LDCs) in

the short term, they will seriously cripple a real chance for African

regional integration.

These EPAs will force other countries, including the US, to demand

the kind of concession that force African countries to do away with

tariff protection before they are ready - ending the potential for the

formation of a single market.

ii. Proposals that focus on USAID eforts and those

on assisting WTO business facilitation must work

towards ensuring that most border formalities are

progressively reduced and eventually dispensed with

completely. Commodities and other factors of pro-

duction entering a regional economic community

through normal procedures should be as free to fow

as those produced within the REC borders. In fact,

all factors of production should fow freely.

Proposal 3: Investment Promotion

Any new initiative should, in addition to trade mea-

sures, seek to include specifc non-trade provisions

on promoting US investment. Tese are, mostly,

encapsulated in the Corporate Council on Africa rec-

ommendations to be released April 17, 2013.

Conclusion

No way etched in stone, our proposals are simple

stakeholder considerations to urge a comprehen-

sive review of U.S. business conditionality. In the

end, the U.S. must adopt a comprehensive legis-

lative plan that, first and foremost shakes off an

uncoordinated engagement strategy that prevents

U.S. businesses from achieving their full poten-

tial in Africa. Secondly, the plan must assure U.S.

investors that a sizably sufficient space exists for

them to operate in the sub Saharan Africa region.

Lastly, any AGOA enhancement must show that

Africas future and place in the global economy

is no longer driven by donor aid but the need for

partnership between equals.

If Obama were to launch a three-point plan like

this one at the 50th Anniversary Africa Union

celebrations, China, the European Union and

other third countries around the world will have

to grapple with the fact that Africa has a true

friend in America after all.

~

SM . SL . DM | Washington, DC | April 2013

Proposal s

vi

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Malaria and Most Vulnerable Populations | Global Health and Gender Policy Brief March 2024Document9 paginiMalaria and Most Vulnerable Populations | Global Health and Gender Policy Brief March 2024The Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Localizing Climate Action: The Path Forward For Low and Middle-Income Countries in The MENA RegionDocument9 paginiLocalizing Climate Action: The Path Forward For Low and Middle-Income Countries in The MENA RegionThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Activating American Investment Overseas for a Freer, More Open WorldDocument32 paginiActivating American Investment Overseas for a Freer, More Open WorldThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Advance An Effective and Representative Sudanese Civilian Role in Peace and Governance NegotiationsDocument4 paginiHow To Advance An Effective and Representative Sudanese Civilian Role in Peace and Governance NegotiationsThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Public Perceptions On Climate Change in QatarDocument7 paginiPublic Perceptions On Climate Change in QatarThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- ECSP Report: Population Trends and The Future of US CompetitivenessDocument17 paginiECSP Report: Population Trends and The Future of US CompetitivenessThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Palestinian Women Facing Climate Change in Marginalized Areas: A Spatial Analysis of Environmental AwarenessDocument12 paginiPalestinian Women Facing Climate Change in Marginalized Areas: A Spatial Analysis of Environmental AwarenessThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Managing Water Scarcity in An Age of Climate Change: The Euphrates-Tigris River BasinDocument13 paginiManaging Water Scarcity in An Age of Climate Change: The Euphrates-Tigris River BasinThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Activating American Investment Overseas For A Freer, More Open WorldDocument32 paginiActivating American Investment Overseas For A Freer, More Open WorldThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women and Girls in WartimeDocument9 paginiWomen and Girls in WartimeThe Wilson Center100% (1)

- How To Restore Peace, Unity and Effective Government in Sudan?Document4 paginiHow To Restore Peace, Unity and Effective Government in Sudan?The Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Cradle of Civilization Is in Peril: A Closer Look at The Impact of Climate Change in IraqDocument11 paginiThe Cradle of Civilization Is in Peril: A Closer Look at The Impact of Climate Change in IraqThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accelerating Africa's Digital Transformation For Mutual African and US Economic ProsperityDocument9 paginiAccelerating Africa's Digital Transformation For Mutual African and US Economic ProsperityThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Africa's Youth Can Save The WorldDocument21 paginiAfrica's Youth Can Save The WorldThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Investing in Infrastructure Bolsters A More Stable, Free and Open WorldDocument2 paginiInvesting in Infrastructure Bolsters A More Stable, Free and Open WorldThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recalibrating US Economic Engagement With Africa in Light of The Implementation of The AfCFTA and The Final Days of The Current AGOA AuthorizationDocument8 paginiRecalibrating US Economic Engagement With Africa in Light of The Implementation of The AfCFTA and The Final Days of The Current AGOA AuthorizationThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- West and North Africa at The Crossroads of Change: Examining The Evolving Security and Governance LandscapeDocument13 paginiWest and North Africa at The Crossroads of Change: Examining The Evolving Security and Governance LandscapeThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Africa's Century and The United States: Policy Options For Transforming US-Africa Economic Engagement Into A 21st Century PartnershipDocument8 paginiAfrica's Century and The United States: Policy Options For Transforming US-Africa Economic Engagement Into A 21st Century PartnershipThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- InsightOut Issue 7 - Turning The Tide: How Can Indonesia Close The Loop On Plastic Waste?Document98 paginiInsightOut Issue 7 - Turning The Tide: How Can Indonesia Close The Loop On Plastic Waste?The Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Addressing Climate Security Risks in Central AmericaDocument15 paginiAddressing Climate Security Risks in Central AmericaThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reimagining Development Finance For A 21st Century AfricaDocument11 paginiReimagining Development Finance For A 21st Century AfricaThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- US-Africa Engagement To Strengthen Food Security: An African (Union) PerspectiveDocument7 paginiUS-Africa Engagement To Strengthen Food Security: An African (Union) PerspectiveThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conference ReportDocument28 paginiConference ReportThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lessons Learned From State-Level Climate Policies To Accelerate US Climate ActionDocument9 paginiLessons Learned From State-Level Climate Policies To Accelerate US Climate ActionThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Avoiding Meltdowns + BlackoutsDocument124 paginiAvoiding Meltdowns + BlackoutsThe Wilson Center100% (1)

- Moments of Clarity: Uncovering Important Lessons For 2023Document20 paginiMoments of Clarity: Uncovering Important Lessons For 2023The Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Africa Year in Review 2022Document45 paginiAfrica Year in Review 2022The Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Security Brief: US Governance On Critical MineralsDocument8 paginiNew Security Brief: US Governance On Critical MineralsThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- InsightOut Issue 8 - Closing The Loop On Plastic Waste in The US and ChinaDocument76 paginiInsightOut Issue 8 - Closing The Loop On Plastic Waste in The US and ChinaThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pandemic Learning: Migrant Care Workers and Their Families Are Essential in A Post-COVID-19 WorldDocument18 paginiPandemic Learning: Migrant Care Workers and Their Families Are Essential in A Post-COVID-19 WorldThe Wilson CenterÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Difference Between Baseband and Broadband TransmissionDocument3 paginiDifference Between Baseband and Broadband Transmissionfellix smithÎncă nu există evaluări

- 12V 60Ah Lead Acid Battery Data SheetDocument4 pagini12V 60Ah Lead Acid Battery Data SheetДима СелютинÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dow Corning Success in ChinaDocument24 paginiDow Corning Success in ChinaAnonymous lSeU8v2vQJ100% (1)

- RR OtherProjectInfo 1 4-V1.4Document1 paginăRR OtherProjectInfo 1 4-V1.4saÎncă nu există evaluări

- NL Back Pressure Valve Brochure 032613Document9 paginiNL Back Pressure Valve Brochure 032613EquilibarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design of Experiments - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument12 paginiDesign of Experiments - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaKusuma ZulyantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- MATH 1003 Calculus and Linear Algebra (Lecture 1) : Albert KuDocument18 paginiMATH 1003 Calculus and Linear Algebra (Lecture 1) : Albert Kuandy15Încă nu există evaluări

- Alignment: Application and Installation GuideDocument28 paginiAlignment: Application and Installation Guideaabaroasr100% (3)

- Skse ReadmeDocument3 paginiSkse ReadmeJayseDVSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Merchant of Veniice Character MapDocument1 paginăMerchant of Veniice Character MapHosseinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contract of SaleDocument3 paginiContract of SaleLeila CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine Department of Education lesson on productivity toolsDocument5 paginiPhilippine Department of Education lesson on productivity toolsKarl Nonog100% (1)

- B1 Editable Quiz 9Document2 paginiB1 Editable Quiz 9Dzima Simona100% (1)

- Facts: Issues: Held:: Eslao v. Comm. On Audit (GR No. 108310, Sept. 1, 1994)Document4 paginiFacts: Issues: Held:: Eslao v. Comm. On Audit (GR No. 108310, Sept. 1, 1994)Stephen Celoso EscartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electricity Markets and Renewable GenerationDocument326 paginiElectricity Markets and Renewable GenerationElimar RojasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Items in The Classroom: Words)Document2 paginiItems in The Classroom: Words)Alan MartínezÎncă nu există evaluări

- COMLAWREV Catindig 2009 ReviewerDocument196 paginiCOMLAWREV Catindig 2009 ReviewerShara LynÎncă nu există evaluări

- Overfishing and Fish Stock DepletionDocument8 paginiOverfishing and Fish Stock DepletionTiger SonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Choong Yik Son V Majlis Peguam MalaysiaDocument5 paginiChoong Yik Son V Majlis Peguam MalaysiaNUR INSYIRAH ZAINIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fact Sheet How To Manage Confidential Business InformationDocument12 paginiFact Sheet How To Manage Confidential Business InformationMihail AvramovÎncă nu există evaluări

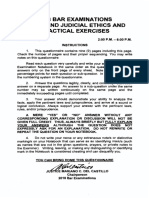

- 2018 Bar Examinations Practical Exercises: Legal and Judicial Ethics andDocument9 pagini2018 Bar Examinations Practical Exercises: Legal and Judicial Ethics andrfylananÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Letters Writing PresentationDocument19 paginiBusiness Letters Writing PresentationHammas khanÎncă nu există evaluări

- IGCSE Syllabus Checklist - ICT (0417)Document15 paginiIGCSE Syllabus Checklist - ICT (0417)Melissa Li100% (1)

- Chapter 1: Introduction To Switched Networks: Routing and SwitchingDocument28 paginiChapter 1: Introduction To Switched Networks: Routing and SwitchingTsehayou SieleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Career Interest Inventory HandoutDocument2 paginiCareer Interest Inventory HandoutfernangogetitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prospectus Ph.D. July 2021 SessionDocument5 paginiProspectus Ph.D. July 2021 SessiondamadolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gildan - Asia - 2019 Catalogue - English - LR PDFDocument21 paginiGildan - Asia - 2019 Catalogue - English - LR PDFKoet Ji CesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessement 8 Mitosis Video RubricDocument1 paginăAssessement 8 Mitosis Video Rubrictr4lÎncă nu există evaluări

- ABI BrochureDocument2 paginiABI BrochureMartin EscolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Main Factors Which Influence Marketing Research in Different Countries AreDocument42 paginiThe Main Factors Which Influence Marketing Research in Different Countries AreHarsh RajÎncă nu există evaluări