Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

2 General

Încărcat de

ajenggayatri0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

41 vizualizări9 paginiTwenty-seven healthy chi l dren aged 35. Years underwent dental rehabi litation under general anesthesia. Combination of local anesthetics and an intravenous nonsteroi dal anti-inflammatory drug ( NSAID) vs NSAID alone on quality of recovery. Parents reported perception of pain and comfort and any occurrences of postoperative cheek biting.

Descriere originală:

Titlu original

2 general

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentTwenty-seven healthy chi l dren aged 35. Years underwent dental rehabi litation under general anesthesia. Combination of local anesthetics and an intravenous nonsteroi dal anti-inflammatory drug ( NSAID) vs NSAID alone on quality of recovery. Parents reported perception of pain and comfort and any occurrences of postoperative cheek biting.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

41 vizualizări9 pagini2 General

Încărcat de

ajenggayatriTwenty-seven healthy chi l dren aged 35. Years underwent dental rehabi litation under general anesthesia. Combination of local anesthetics and an intravenous nonsteroi dal anti-inflammatory drug ( NSAID) vs NSAID alone on quality of recovery. Parents reported perception of pain and comfort and any occurrences of postoperative cheek biting.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 9

The Effect of Local Anesthetic on Quality of

Recovery Characteristics Following Dental

Rehabilitation Under General Anesthesia

in Children

Janice A. Townsend, DDS, MS,* Steven Ganzberg, DMD, MS, and

S. Thikkurissy, DDS, MS`

*Assistant Professor, LSU School of Dentistry, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, New Orleans, Louisiana, Professor of Clinical

Anesthesiology, College of Dentistry, College of Medicine and Public Health, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio,

and `Assistant Professor, The Ohio State College of Dentistry, Columbus, Ohio

This study is a randomized, prospective, double-blind study to evaluate the effects

of the combination of local anesthetics and an intravenous nonsteroi dal anti-in-

flammatory drug ( NSAID) vs NSAID alone on quality of recovery following dental

rehabilitation under general anesthesia ( GA). Twenty-seven healthy chi l dren aged

3^5.5 years underwent dental rehabi litation under GA. Fifteen chi l dren in the

experimental group received oral infi ltration of local anesthetic in addition to in-

travenous ketorolac tromethami ne, whi le 12 chi l dren i n the control group re-

ceived intravenous ketorolac tromethamine alone for postoperative pain manage-

ment. Pain behaviors were evaluated immediately postoperatively using a FLACC

scale and 4 hours postoperatively by self-report using various scales. Parents re-

ported perception of chi l d pain and comfort and any occurrences of postopera-

tive cheek biting. The use of intraoral infi ltration local anesthesia for complete

dental rehabi litation under general anesthesia for chi l dren aged 3^5.5 years di d

not result in improved pain behaviors in the postanesthesia care unit ( PACU), nor

di d it result in improved pain behaviors 4^6 hours postoperatively as measured

by the FLACC scale, FACES scale, and subjective reports of parents or a PACU

nurse. Those chi l dren receiving local anesthesia had a higher inci dence of nega-

tive symptoms related to local anesthetic administration, including a higher inci-

dence of lip and cheek biting, which was of clinical importance, but not statisti-

cally significant. Infiltration of local anesthetic for dental rehabi litation under gen-

eral anesthesia di d not improve quality of recovery in chi l dren aged 3^5.5 years.

Key Words: General anesthesia; Pediatric dental general anesthesia; Pain; Local anesthesia; Recovery quality.

D

ental rehabi litation under general anesthesia is

commonly performed i n young chi l dren be-

cause chi l dren may be unable to cooperate i n a dental

cli ni c setti ng or because they may require a signifi cant

amount of dental work.

1

The use of general anesthe-

si a for dental rehabi litation of chi l dren, when i ndi cat-

ed, i s an accepted behavior management techni que

accordi ng to the Ameri can Academy of Pedi atri c Den-

ti stry ( AAPD).

1

Although benefits of general anesthe-

si a for denti stry i ncl ude safe and effi ci ent delivery of

dental care, the procedure i s not without morbi dity or

mortality.

2

A well- documented phenomenon in medicine is

the undertreatment of pain in chil dren. Pain has been un-

dertreated across all age groups due to misunderstand-

ings about analgesic use and concerns over addiction,

Received June 3, 2008; accepted for publi cation November 6,

2008.

Address correspondence to Dr Janice A. Townsend, Assistant

Professor, LSU School of Dentistry, Department of Pediatric

Dentistry, 1100 Flori da Ave, New Orleans, LA 70119; jtown2@

lsuhsc.edu.

SCIENTIFIC REPORT

Anesth Prog 56:115^122 2009

E

2009 by the American Dental Society of Anesthesiology

ISSN 0003-3006/09

SSDI 0003-3006(09)

115

and, in youngchil dren, the mistaken belief of nopainper-

ception.

3

The American Academy of Pediatrics ( AAP)

and theAmerican Pain Society ( APS) issued joint recom-

mendations in 2001 to eliminate pain-related suffering.

Pain is defined as a subjective experience that is the prod-

uct of both emotional and sensory components interrelat-

ed with the context of culture and environment. Suffering

occurs when pain is uncontrolled and the patient feels

overwhelmed and out of control.

4

One goal for all

medical and dental practitioners i s to vigi lantly moni-

tor pai n to prevent suffering. Given the fact that, his-

tori cally, pain has been undertreated in chi l dren and

measurement tools exist that help quantify pedi atri c

pai n, clini cal trials shoul d be undertaken to deter-

mi ne best practices in this area.

The topic of morbi dity following dental treatment

under general anesthesia has been a popular area for

research in recent years predominantly in the United

Kingdom as a result of a report by the Expert Working

Party on General Anesthesia chaired by Professor Pos-

willo. In response to this sobering report, studies have

attempted to measure postoperative morbi dity

5

and

local anesthesia has been looked upon favorably as a

potential techni que to improve outcomes with varying

levels of success.

2

Jurgens et al

6

coul d not fi nd a stati sti cal ly signifi cant

difference i n self-reported postoperative pai n between

chi l dren treated with local anestheti c compared with

those treated with systemi c analgesi cs ( i ntravenous

fentanyl and paracetamol [acetami nophen] either

alone or i n combi nation) for dental extractions, but

subjectively determi ned that the chi l dren appeared

more settled i n recovery. Atan et al

2

reported that

the odds of experi enci ng pai n at the operation site

were reduced by local analgesi a by an odds ratio of

0.39, but these chi l dren were more likely to report

dizzi ness. Two other studi es found a signifi cant bene-

fit to i ntraligamental i njection but only at one i so-

lated time i n the immedi ate postoperative period

( 5 mi nutes).

7,8

Coulthard et al

9

examined postoperative pain fol-

lowing extractions under general anesthesia. In that

double-blind study of 142 chi l dren aged 4^12 years

who received 15 mg/kg of acetaminophen 1 hour pre-

operatively and acetaminophen elixir for home, infil-

tration of local anesthetic di d not improve postopera-

tive pain reports. McWi lliams and Rutherford

10

found

that local anesthetic decreased postoperative bleeding

but had no effect on behavior. Al-Bahlani et al

11

agreed that local anesthetic was related to a significant

reduction in perioperative bleeding but also found a

statistically significant increase in distress. It is impor-

tant to note that the dentistry in these studies consist-

ed of extractions almost exclusively.

The AAPD gui delines note that local anesthesia has

been reported to reduce pain in the postoperative re-

covery period after general anesthesia; however, the

citations used to support this statement provi de mar-

ginal evi dence.

12,13

The overall objective of this study

was to provi de practitioners with more information on

how to reduce postoperative pain and improve recov-

ery characteristics in chil dren following dental surgery

under general anesthesia. Specifically, this is a ran-

domized, prospective, double-blind study to evaluate

the effects of the combination of local anesthetics and

an intravenous nonsteroi dal anti-inflammatory drug

( NSAID) vs the effects of NSAID alone in reducing

postoperative pain and improving immediate postop-

erative recovery and recovery later on the day of sur-

gery. No opioi ds, such as morphine sulfate, were used

to assess more accurately the contribution of local an-

esthetic per se to postoperative behaviors.

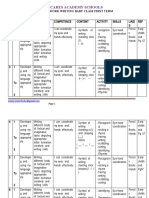

Pain behaviors were evaluated immediately after the

surgery using a FLACC ( faces, legs, activity, crying,

and consolability) scale by a trained examiner ( Fig-

ure 1). The FLACC score has been vali dated in chi l-

dren aged 2 months to 7 years

14

and requires a brief

period of training to achieve high interrater reliabili-

ty.

15

In addition, pain intensity was evaluated immedi-

ately postoperatively and the evening of the surgery

with the Wong-Baker FACES scale administered to

participant chil dren. This scale consists of 6 cartoon

faces with varying expressions ranging from very hap-

py to very sad and has been vali dated for chil dren

aged 3^7 years

16,17

( Figure 2). Parents also evaluated

their perception of the chil ds pain the evening of sur-

gery using a 1^10 visual analog scale ( VAS) and were

asked to report any occurrences of postoperative

cheek biting as well as subjective comments about

their chil ds behavior at home within the first few post-

operative hours.

The specific aim of this research was to determine

whether local anesthesia administered with an intrave-

nous NSAID improved the quality of recovery for chil-

dren in the immediate postoperative period and while

at home later in the day.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Board of Nationwi de Chi l-

drens Hospital in Columbus, Ohio reviewed and ap-

proved this study prior to commencement. A conve-

nience sample of 27 subjects was recruited for this

study at the Dental Surgery Center at Nationwi de Chil-

drens Hospital. Subjects were chi l dren between 3 and

5.5 years of age undergoing general anesthesia for

dental rehabi litation; they spoke English, had a phone

116 Effect of Local Anesthetic Following GA Anesth Prog 56:115^122 2009

where they coul d be reached, were ASA I or II, and

were free of any developmental delays or psychiatric

conditions, including attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder. Inclusion criteria required that the dental sur-

gical procedures include a minimum of either 2 ante-

rior preveneered crowns or 2 anterior extractions ( in

order for lip anesthesia to be experienced in the local

anesthesia group) and a minimum of 4 stainless steel

crowns with at least 1 in the maxi llary arch and 1 in the

mandibular arch ( in order that teeth in both the maxi l-

lary and mandibular posterior arches woul d also be

anesthetized). Patients with a history of adverse drug

reactions or medical contraindications to any analge-

sic or anesthetic agents used in the study were exclud-

ed. If the total amount of local anesthetic the chi l d re-

quired exceeded 7 mg/kg of li docaine ( with epineph-

rine 1 : 100,000), then the chi l d was also excluded.

Prior to inclusion, informed consent was obtained

by the study investigator from a legal guardian for each

chil d. Demographic information, such as age, weight,

and sex, was recorded about the patient.

Patients underwent general anesthesia according to

the long-standing protocols. General anesthesia was

induced with sevoflurane in oxygen; nasotracheal in-

tubation was accomplished with propofol, 1^2 mg/kg

intravenously, without neuromuscular blockade, fol-

lowed by anesthetic maintenance with isoflurane in

50% nitrous oxi de with oxygen. Dexamethasone,

0.1 mg/kg intravenously, was administered at induc-

tion or very early in the case prior to surgical interven-

tion. Approximately 10^20 minutes prior to case com-

pletion, isoflurane was discontinued targeting 0% ex-

pired isoflurane at case termination, and general

anesthesia was maintained during this interval with

propofol boluses and 66% nitrous oxi de in oxygen.

Subjects were extubated unconsciously after several

breaths of 100% oxygen and transferred to the postan-

esthesia care unit ( PACU) when nearing wakefulness.

The dental surgeons were pediatric dental faculty, pri-

vate practitioner pediatric dentists, and second year

pediatric dental resi dents.

Subjects were assigned by a random number gener-

ator to either a control or experimental group. The

control group received 1 mg/kg ketorolac intravenous-

ly within 15 minutes of case completion. The experi-

mental group received 1 mg/kg ketorolac within

15 minutes of case completion as well as local anes-

thetic infi ltration. Two percent li docaine with

1: 100,000 epinephrine was infi ltrated on the buccal

and lingual mucosa of each tooth treated. No inferior

alveolar block anesthesia was provi ded. A standard-

ized amount of 0.3 mL was administered for each

tooth with stainless steel crowns or extractions ( not

for composite or amalgam restorations) uti lizing pre-

marked dental cartri dges, not to exceed 7.0 mg/kg

based on li docaine dosage. The anesthetic infiltration

took place prior to the commencement of the last sex-

tant of operative dentistry. The surgeon and anesthesi-

ologist were not blinded to local anesthetic adminis-

tration in this study to allow for proper emergency

care and record-keeping.

After transfer to PACU, subjects were monitored by

a registered nurse. The nurse, who was blinded to local

anesthetic status, evaluated the patient at 5-minute in-

tervals using the FLACC assessment tool. The nurse

also attempted to record patient self-assessment of

pain using the Wong-Baker FACES scale and recorded

subjective comments about patient behavior. All perti-

nent surgical and PACU times were recorded. Parents

were present in the PACU when subjects were trans-

ferred there, and parents were also blinded as to local

anesthetic administration. A standard discharge script

with postoperative instructions that advised parents to

watch for signs of self-muti lation, such as cheek biting,

was given to each caregiver. The instruction sheet also

advised the parents to give acetaminophen (15 mg/

kg) 4 to 6 hours after discharge, and a bottle of Chil-

drens Tylenol was dispensed. A phone number where

Figure1. FLACC scale.

14

Categories

Scoring

0 1 2

Face No particular expression or

smile

Occasional grimace or frown, withdrawn,

disinterested

Frequent to constant quivering

chin, clenched jaw

Legs Normal position or relaxed Uneasy, restless, tense Kicking, or legs drawn up

Activity Lying quietly, normal

position, moves easi ly

Squirming, shifting back and forth, tense Arched, rigi d or jerking

Cry No cry ( awake or asleep) Moans or whimpers; occasional complaint Crying steadi ly, screams or sobs,

frequent complaints

Consolability Content, relaxed Reassured by occasional touching,

hugging or being talked to, distractible

Difficult to console or comfort

Anesth Prog 56:115^122 2009 Townsend et al 117

the parents coul d be reached 4 to 6 hours after dis-

charge was recorded.

Four to six hours after discharge from the PACU,

parents were contacted by phone by a research inves-

tigator blinded as to the experimental group. The par-

ents were asked to evaluate the patients pain level on

a provi ded 10-point VAS as well as to obtain a self-re-

port of the chil ds pain using the FACES assessment

tool. Parents were also asked to report analgesic use,

cheek or lip biting, and subjective reports of behavior.

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using

JMP ( SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and GraphPad Prism

Statistical Software ( Graph Software, San Diego, Ca-

lif). An unpaired t test was used to analyze weight, res-

torations placed, and various operative times. A Fisher

exact test was used to analyze sex differences and re-

porting of negative comments. A Wi lcoxon rank sum

test was used to analyze the postoperative FLACC

score, the parent VAS score, and the chil d FACES

score. All statistical analyses assumed a P level # .05

to be significant. A priori, we determined that the fol-

lowing were clinically significant differences on test-

ing: 2 for the FLACC score, 2 for the FACES score,

and 3 for the VAS score.

RESULTS

Consent was obtained from parents prior to surgery

for 48 chil dren whose preoperative dental exam indi-

cated they woul d meet the inclusion criteria. After ex-

amination and radiographs, 27 chi l dren met the inclu-

sion criteria, with 15 in the li docaine group and 12 in

the control group. A number of chi l dren assigned to

the li docaine group were excluded from the study be-

cause the amount of local anesthesia woul d have ex-

ceeded 7 mg/kg due to a large number of teeth re-

quiring treatment, and the protocol prevented reas-

signing chi l dren to the control group.

Eight female and 19 male participants completed

the study. There were no statistically significant differ-

ences in sex, age, or weight between groups, although

weight approached significance ( control [C], 15.34 6

2.34 kg vs li docaine [L], 18.50 6 5.38 kg; P , .07)

( Table 1).

When analyzing the number and type of procedures

in the 2 groups, none of the indivi dual procedure to-

tals per case reached significance with an unpaired t

test between the li docaine and control groups ( Ta-

ble 2). Length of the case ( C, 91 6 34 minutes vs L,

73 6 12 minutes; P .10), total PACU time ( C, 20 6

4 minutes vs L, 20 6 6 minutes; P ,.96), and time to

eye opening ( C, 12 614 minutes vs L, 9 65 minutes;

P ,.47) di d not differ significantly between groups.

FLACC scores were recorded by a registered nurse

in the PACU at 5-minute intervals and interpreted us-

ing a Wi lcoxon rank sum test. The times of awakening,

degree of recovery at any time period, and discharge

time in patients were variable, and therefore a compar-

ison of all subjects at a set time period woul d not yiel d

a vali d comparison. The FLACC score at 15 minutes in

the PACU captured the most chi l dren awake and yet

not discharged ( N 5 22). Almost all participants were

discharged by 30 minutes and FLACC scores were not

noted to be very different from 15 minutes to dis-

charge. For all but 3 participants, this was the same

as the 15-minute postoperative FLACC score. For the

3 participants who had different discharge FLACC

scores from the 15-minute FLACC score, the differ-

ence was only 1 unit for all participants (0 R1; 5 R

4; 1 R0) and not clinically significant. A priori, it was

determined that a difference of greater than 2 woul d

be consi dered clinically significant. Only 1 patient was

discharged prior to 15 minutes and that FLACC score

was zero at 10 minutes, so no change was anticipated

in that participant. Therefore, the FLACC score closest

to discharge was used for comparison. The mean

FLACC score at discharge di d not differ between the

experimental or control groups ( L, 2.47 6 2.69 vs C,

2.58 6 2.54; P ,.88). The highest FLACC score pro-

vi des another means for comparison. There was no

Table1. Participant Demographics

Experimental Control P Value

Female sex 5 3 .6957

Weight ( kg) 18.5 65.38 15.34 62.34 .074

Age ( years) 4.3 60.78 3.8 60.68 .11

Table 2. Average Number of Restorations Per Group

Experimental Control P Value

Stainless steel crowns 7.200 60.6264 7.500 60.6455 .7438

Preveneer anterior crowns 2.867 60.5762 2.385 60.3846 .5067

Pulpotomies 3.200 60.7051 1.583 60.5288 .0914

Pulpectomies 1.133 60.5595 0.7500 60.4459 .6104

Anterior extractions 2.200 60.6188 1.500 60.4846 .4000

Posterior extractions 0.7333 60.2282 0.3333 60.3333 .3172

118 Effect of Local Anesthetic Following GA Anesth Prog 56:115^122 2009

significant difference between groups based on high-

est FLACC score (P ,.84).

The immediate postoperative FACES score was dif-

ficult to obtain due to variable cooperation of subjects

in the immediate postoperative period and therefore

yiel ded insufficient data for analysis.

Twenty-three of the 27 subjects were reached for a

postoperative phone call. There was no significant dif-

ference in time of parent contact for postoperative

phone call from PACU discharge between groups ( L,

277 634 minutes vs C, 311 696 minutes; P ,.28).

Of these, 23 subjects whose parents were contacted,

20 were able to self-report pain using the FACES

scale, 10 in the experimental and 10 in the control

group. These scores were simi lar between groups ( L,

0.30 6 0.21 vs C, 0.60 61.35; P ,.92), using a Wi l-

coxon rank sum analysis as shown in Figure 3. The

VAS scores reported by the parents were also similar

(P , .74) as shown in Figure 4, but clearly, this is a

subjective measure without internal vali dity.

The number of chi l dren requiring oral analgesics at

home, as reported by parents, was not different, based

on the Fisher exact test, between the two groups ( L, 2

of 11 vs C, 4 of 12; P ,.70) with the majority (17 of 23

subjects; 74%) not needing additional pain medication

beyond the intraoperative intravenous ketorolac with

or without local anesthesia.

When asked if subjects had been observed biting

their lips or cheeks, more chi l dren from the local anes-

thetic group ( 4 of 11; 36%) reported biting than from

the control group (1 of 12; 8%), although the results

were not significant with a Fisher exact test (P ,

.155). When asked if physical damage to the oral tis-

sues was observed, only 2 chil dren from the local an-

esthetic group (2 of 15; 13%) reported damage to oral

tissues vs the control group (0 of 18; 0%). The report of

visible damage to the oral structures was not signifi-

cant with the Fisher exact test ( P , .22) as shown in

Figure 5.

Parents were asked for subjective comments about

their chil ds behavior postoperatively. A category

called Negative Comments was added for chi l dren

who demonstrated distressed behavior. Only the par-

ents of chil dren who received local anesthetic in addi-

tion to ketorolac ( 3 of 15 chil dren; 20%), reported

negative comments. None of the parents of chil dren

who received ketorolac alone reported negative com-

Figure 3. Postoperative phone call FACES scores.

Figure 4. Postoperative phone call VAS scores.

Fi gure 5. Ti ssue damage postoperat i vel y reported by

parents.

Figure 2. Wong-Baker FACES scale.

16

Anesth Prog 56:115^122 2009 Townsend et al 119

ments. The presence of negative symptoms was, how-

ever, not statistically significant with a Fisher exact test

(P ,.09) as shown in Figure 6. Examples of negative

comments included: He cried for a half hour. He

di dnt like the numb feeling and coul dnt eat; He was

pulling on his lips. He coul dnt eat or drink; She was

biting her lip when she first woke up; He was biting

and pulling at his lips on the way home; and She

di dnt like the feeling of her front teeth and com-

plained they felt tingly.

DISCUSSION

Pediatric dental rehabi litation is performed under gen-

eral anesthesia to treat chi l dren unable to cooperate in

a dental setting to provi de high- quality dental surgical

care in an environment that causes minimal distress to

patients and parents. The findings of this study suggest

that local anesthetic has no beneficial effect on pain

behaviors postoperatively following comprehensive

pediatric dentistry under general anesthesia.

Our fi ndi ngs support Al-Bahlanis previous fi ndi ng

of i ncreased di stress i dentifi ed with local anestheti c

use.

11

Parents were able to i dentify negative behav-

iors secondary to the sensation of numbness, i n spite

of bei ng bli nded to local anestheti c usage. Examples

of parents comments were: She was fussy unti l the

numbi ng wore off; She was clawi ng at her mouth

and scratchi ng her lips; and She had a hard time

eati ng or dri nki ng. These responses were grouped

i n the results as Negative Comments, and although

the val ue was not stati sti cal ly signifi cant, the number

of cases was cli ni cal ly signifi cant ( 3 of 15 for the lo-

cal anesthesi a group vs 0 of 18 for the ketorolac only

group). We consi der thi s cli ni cal ly signifi cant because

it occurred with 20% of the chi l dren i n the experi-

mental group whose caregivers were contacted.

When 1 out of 5 chi l dren treated under general anes-

thesi a perceive di scomfort due to the sensation of

numbness, then quality of recovery i s not optimal.

The parents of chi l dren with negative symptoms sec-

ondary to local anestheti cs reported their chi l dren

were i n di stress unti l the local anestheti c sensations

wore off. Though one of the aims of thi s study was to

determi ne improvement i n the postoperative experi-

ence with local anestheti cs, the outcome seems to

show the opposite to be true.

The i nci dence of cheek and lip biti ng di d not reach

stati sti cal signifi cance but, agai n, the i nci dence report-

ed i s cli ni cal ly signifi cant due to the di scomfort associ-

ated with oral trauma ( L, 2 of 15 vs C, 0 of 18). Agai n,

thi s i s deemed cli ni cal ly signifi cant because approxi-

mately 13% of chi l dren were affected. The smal l sam-

ple size may also have not al lowed stati sti cal signifi-

cance to be demonstrated. None of the pati ents re-

quired a fol low- up vi sit because the degree of oral

trauma was not concerni ng enough for parents, even

with a fol low- up phone cal l on postoperative day 1.

Our fi ndi ng of 13% postoperative cheek biti ng i s not

di ssimi lar to the 18% i nci dence of trauma fol lowi ng

mandi bular block anesthesi a by Col lege et al

18

i n se-

dated and nonsedated chi l dren. Postoperative lip and

cheek biti ng i nj uri es were also found by Coulthard et

al

9

who found i nj uri es i n 1 of 69 control pati ents and

3 of 70 local anesthesi a pati ents. The authors conjec-

tured that i n chi l dren the alteration of sensation i s

more di stressi ng when it occurs i n the orofaci al area

as opposed to other surgi cal areas because the face i s

more highly i nnervated, and therefore they are more

aware of it.

9

Other reasons may i ncl ude the i nabi lity

to vi ew the area of anatomy with altered sensation as

i s possi ble with any other area of anatomy as wel l as

the unconscious importance of the mouth to chi l dren.

Another interesting result was found when review-

ing the pattern of FLACC scores. There was minimal

change in FLACC scores for any indivi dual subject

during the overall PACU stay. In other words, those

participants who were comfortable on awakening were

likely to be so at discharge, and those who awoke ex-

hibiting discomforting behaviors, continued to do so

during the short PACU stay, which averaged 20 min-

utes. Regardless, the majority of chil dren whose par-

ents were contacted by phone, 17 of 23, di d not re-

quire additional analgesics later in the day ( L, 2 of 11

vs C, 4 of 12; P ,.695). This is interesting consi dering

that a significant amount of dental treatment was pro-

vi ded in both groups.

This is one of the very few studies that have been

conducted on pain perception following dental reha-

bilitation, under fully intubated general anesthesia in

chi l dren, especially with a double-blind design. Previ-

Figure 6. Negati ve symptoms postoperati vel y reported

by parents.

120 Effect of Local Anesthetic Following GA Anesth Prog 56:115^122 2009

ous studies have exclusively studied pain perception

after extractions only. The presence of tooth prepara-

tion and restoration in addition to extractions may

have different effects on the perception of postopera-

tive pain, and their inclusion is a major strength of this

study.

The primary study weakness is the small sample

size. A larger cohort might have uncovered statistically

significant differences in those parameters that ap-

proached clinical significance. Since this is a novel ar-

ea of study, attempts at a pre-study power analysis

proved arbitrary. Therefore, a convenience sample

was recruited using rigi d inclusion criteria to ensure

simi larity between the 2 groups. As a result, sample

sizes were low. However, this research provi des a

foundation for future studies in this area with a more

appropriate sample size.

Other changes in methodology woul d strengthen fu-

ture study designs. Preoperative FLACC and FACES

scores woul d control for the presence or absence of

preoperative pain. Reliabi lity testing for the nurse eval-

uator was not conducted in this study since one nurse

was used throughout. However, intrarater reliabi lity

tests coul d have ensured more consistent evaluation

of postoperative FLACC scores. Previous research

demonstrates that parents can be trained in the

FLACC assessment tool in a brief period of time. In

future studies, a parental FLACC assessment at home

at more frequent intervals coul d strengthen the post-

operative evaluation process. Additionally, the study

design that limited li docaine administration to 7 mg/

kg resulted in ol der chil dren, possibly those with more

dental work required and those weighing more, being

in the experimental local anesthetic group. The ol der

group may have skewed results, especially with this

small sample size.

In conducting the study, it was interesting to note

that some practitioners, both dentists and 1 dentist an-

esthesiologist, felt so strongly about their preferred

techni que of practicing, that they were either unwi ll-

ing to participate in the study or expressed discomfort

at being assigned to a group other than their preferred

method. Despite the lack of research in the area, both

practitioners who routinely administered local anes-

thetic and those who do not were confi dent that

switching techni ques woul d affect patient recovery.

This vali dates the need for the profession to continual-

ly challenge our practices to avoi d continuation of in-

effective techni ques. It shoul d also be noted that

7.0 mg/kg of li docaine, the maximum dose for the

monitored patient with full emergency capability im-

mediately available, was used in this study. This is

more than the AAPD recommended maximum of

4.4 mg/kg, which assumes an unmonitored patient

and possibly the addition of inhalation and oral seda-

tives.

In light of the absence of beneficial effects of the use

of local anesthetic and the presence of negative symp-

toms, this study does not support use of local anes-

thetics during dental rehabilitation under general an-

esthesia to decrease postoperative pain. Alternative

methods of pain control shoul d be investigated that

avoi d altered orofacial sensation. The use of intraoper-

ative opioi ds, such as morphine sulfate, with or with-

out intravenous NSAIDs, appears to result in a greater

inci dence of calm chi l dren in the PACU as reported

anecdotally by our PACU nurse.

REFERENCES

1. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Gui deline

on behavior gui dance for the pediatric dental patient. Pediatr

Dent. 2006^2007;28( suppl ) :97^105.

2. Atan S, Ashley P, Gi lthorpe MS, Scheer B, Mason C,

Roberts G. Morbi dity following dental treatment of chi l dren

under intubation general anaesthesia in a day-stay unit.

Int J Paediatr Dent. 2004;14:9^16.

3. Schechter N. The undertreatment of pain in chil dren:

an overview. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1989;36:781^794.

4. American Academy of Pediatrics and American Pain

Society. The assessment and management of acute pain in

infants, chil dren, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2001;108:

793^797.

5. Bri dgman CM, Ashby D, Holloway PJ. An investiga-

tion of the effects on chil dren of tooth extraction under gen-

eral anaesthesia in general dental practice. Br Dent J.

1999;186:245^247.

6. Jurgens S, Warwick RS, Inglehearn PJ, Gooneratne

DS. Pain relief for paediatric dental chair anaesthesia: cur-

rent practice in a community dental clinic. Int J Paediatr

Dent. 2003;13:93^97.

7. Sammons HM, UnsworthV, Gray C, Choonara I, Cher-

ri ll J, Quirke W. Randomized controlled trial of the intraliga-

mental use of a local anaesthetic ( lignocaine 2%) versus con-

trols in paediatric tooth extraction. Int J Paediatr Dent.

2007;17:297^303.

8. Leong KJ, Roberts GJ, Ashley PF. Perioperative local

anaesthetic in young paediatric patients undergoing extrac-

tions under outpatient short-case general anaesthesia. A

double-blind randomized controlled trial. Br Dent J. 2007;

203:334^335.

9. Coulthard P, Rolfe S, Mackie IC, Gazal G, Morton M,

Jackson-Leech D. Intraoperative local anaesthesia for paedi-

atric postoperative oral surgery paina randomized con-

trolled trial. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:1114^1119.

10. McWi lliams PA, Rutherford JS. Assessment of early

postoperative pain and haemorrhage in young chi l dren un-

dergoing dental extractions under general anaesthesia.

Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007;17:352^357.

Anesth Prog 56:115^122 2009 Townsend et al 121

11. Al-Bahlani., Sherriff A, Crawford PJM. Tooth extrac-

tion, bleeding, and pain control. J R Coll Surg Edinb.

2001;46:261^264.

12. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Gui deline

on appropriate use of local anesthesia for pediatric dental

patients. Pediatr Dent. 2006^2007;28( suppl ) :106^111.

13. Nick D, Thompson L, Anderson D, Trapp L. The use of

general anesthesia to facilitate dental treatment. Gen Dent.

2003;51:464^468.

14. Merkel SI, Voepel-Lewis T, Shayevitz JR, Malviya S.

The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative

pain in young chi l dren. Pediatr Nurs. 1997;23:293^297.

15. Manworren RC, Hynan LS. Clinical vali dation of

FLACC: preverbal patient pain scale. Pediatr Nurs. 2003;

29:140^146.

16. Wong DL, Baker CM. Pain in chil dren: comparison of

assessment scales. Pediatr Nurs. 1988;14:9^17.

17. Bosenberg A, Thomas J, Lopez T, Kokinsky E, Larsson

LE. Vali dation of a six-graded faces scale for evaluation of

postoperative pain in chil dren. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13:

708^713..

18. College C, Feigal R, Wandera A, Strange M. Bilateral

versus uni lateral mandibular block anesthesia in a pediatric

population. Pediatr Dent. 2000;22:453^457.

122 Effect of Local Anesthetic Following GA Anesth Prog 56:115^122 2009

Copyright of Anesthesia Progress is the property of Allen Press Publishing Services Inc. and its content may not

be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written

permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Anesthesia Onset Time and Injection Pain Between Buffered and Unbuffered Lidocaine Used As Local Anesthetic For Dental Care in ChildrenDocument4 paginiAnesthesia Onset Time and Injection Pain Between Buffered and Unbuffered Lidocaine Used As Local Anesthetic For Dental Care in ChildrenFernando MenesesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Efficacy of Benzocaine 20% Topical Anesthetic Compared To Placebo Prior To Administration of Local Anesthesia in The Oral Cavity: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument5 paginiEfficacy of Benzocaine 20% Topical Anesthetic Compared To Placebo Prior To Administration of Local Anesthesia in The Oral Cavity: A Randomized Controlled TrialAlina AlexandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dental JurnalDocument12 paginiDental JurnalSiti HajarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Synopsis: ST John'S College of NursingDocument19 paginiSynopsis: ST John'S College of NursingsyarifaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pan 13575Document2 paginiPan 13575Reynaldi HadiwijayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Policy On Pediatric Dental Pain ManagementDocument3 paginiPolicy On Pediatric Dental Pain ManagementمعتزباللهÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brignardello Petersen2018Document1 paginăBrignardello Petersen2018Daniella NúñezÎncă nu există evaluări

- AL Computarizada Vs TradicionalDocument5 paginiAL Computarizada Vs TradicionalClaudia ZuluagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Prospective Audit of Pain Profiles Following General and Urological Surgery in ChildrenDocument10 paginiA Prospective Audit of Pain Profiles Following General and Urological Surgery in ChildrenLakhwinder KaurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Study: Postoperative Pain After Root Canal Treatment: A Prospective Cohort StudyDocument6 paginiClinical Study: Postoperative Pain After Root Canal Treatment: A Prospective Cohort StudyUtami QÎncă nu există evaluări

- P AcutepainmgmtDocument5 paginiP AcutepainmgmtLeticia Quiñonez VivasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acup Utk TonsiltektomiDocument7 paginiAcup Utk Tonsiltektominewanda1112Încă nu există evaluări

- 2019 Zhang - A Study On The Prevalence of Dental Anxiety Pain Perception and TheirDocument8 pagini2019 Zhang - A Study On The Prevalence of Dental Anxiety Pain Perception and Theirfabian.balazs.93Încă nu există evaluări

- Acc Pain FauziDocument8 paginiAcc Pain FauziMuchlis Fauzi EÎncă nu există evaluări

- Randomized Clinical Trial of Intraosseous Methylprednisolone Injection For Acute Pulpitis PainDocument6 paginiRandomized Clinical Trial of Intraosseous Methylprednisolone Injection For Acute Pulpitis PainFrançois BronnecÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Analgesics On Orthodontic Pain: Online OnlyDocument6 paginiEffects of Analgesics On Orthodontic Pain: Online OnlyPae Anusorn AmtanonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jop 21 4 Toure 4Document6 paginiJop 21 4 Toure 4digdouwÎncă nu există evaluări

- Narcotic Analgesia in AppendicitisDocument2 paginiNarcotic Analgesia in AppendicitisAdil KhurshidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Female and PainDocument5 paginiFemale and PainMiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Academic Emergency Medicine - 2008 - Kim - A Randomized Clinical Trial of Analgesia in Children With Acute Abdominal PainDocument9 paginiAcademic Emergency Medicine - 2008 - Kim - A Randomized Clinical Trial of Analgesia in Children With Acute Abdominal PainBrandon ChavarriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DTM Examenes en Dinamica y EstaticaDocument0 paginiDTM Examenes en Dinamica y EstaticaAndrea Seminario RuizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patient Safety During Sedation by Anesthesia ProfeDocument8 paginiPatient Safety During Sedation by Anesthesia ProfeIsmar MorenoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medoral 20 E459Document5 paginiMedoral 20 E459Tania RodriguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Alternative Local Anaesthesia Technique To Reduce Pain in Paediatric Patients During Needle InsertionDocument4 paginiAn Alternative Local Anaesthesia Technique To Reduce Pain in Paediatric Patients During Needle InsertionNisa Nafiah OktavianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chemotherapy-Associated Oral Sequelae in Patients With Cancers Outside The Head and Neck RegionDocument10 paginiChemotherapy-Associated Oral Sequelae in Patients With Cancers Outside The Head and Neck RegionNndaydnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Doctor Opinion Versus A Patient Questionnaire For The Outcome Assessment of Treated Temporomandibular Disorder PatientsDocument3 paginiGlobal Doctor Opinion Versus A Patient Questionnaire For The Outcome Assessment of Treated Temporomandibular Disorder PatientsAlejandro Pérez PinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Angle 2011, Self-Reported Pain Associated With The Use of Intermaxillary Elastics Compared To Pain Experienced After Initial Archwire PlacementDocument5 paginiAngle 2011, Self-Reported Pain Associated With The Use of Intermaxillary Elastics Compared To Pain Experienced After Initial Archwire PlacementTarif HamshoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lingual Nerve TreatmentDocument9 paginiLingual Nerve TreatmentAlin OdorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dellepiani 2020Document7 paginiDellepiani 2020IsmaelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anesthetic Efficacy of Buccal Infiltration Articaine Versus Lidocaine For Extraction of Primary Molar TeethDocument5 paginiAnesthetic Efficacy of Buccal Infiltration Articaine Versus Lidocaine For Extraction of Primary Molar TeethFabro BianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Synergistic Interaction Between Fentanyl and Bupivacaine Given Intrathecally For Labor AnalgesiaDocument11 paginiSynergistic Interaction Between Fentanyl and Bupivacaine Given Intrathecally For Labor AnalgesiaNurul Dwi LestariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Original Article: Dental Research, Dental Clinics, Dental ProspectsDocument8 paginiOriginal Article: Dental Research, Dental Clinics, Dental Prospectsmadhu kakanurÎncă nu există evaluări

- OgundipeDocument6 paginiOgundipeIria GonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Angle Orthod. 2016 86 4 625-30Document6 paginiAngle Orthod. 2016 86 4 625-30brookortontiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2012 Nourbakhsh Effect of Phentolamine Mesylate On Duration of Soft Tissue Local Anesthesia in ChildrenDocument8 pagini2012 Nourbakhsh Effect of Phentolamine Mesylate On Duration of Soft Tissue Local Anesthesia in ChildrenBryant LewisÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Efficacy of Honey For Ameliorating Pain After TonsillectomyDocument8 paginiThe Efficacy of Honey For Ameliorating Pain After TonsillectomyAzmeilia LubisÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Clinical Audit Into The Success Rate of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block Analgesia in General Dental PracticeDocument4 paginiA Clinical Audit Into The Success Rate of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block Analgesia in General Dental PracticeGina CastilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discomfort Associated With Invisalign and Traditional Brackets: A Randomized, Prospective TrialDocument8 paginiDiscomfort Associated With Invisalign and Traditional Brackets: A Randomized, Prospective TrialLima JúniorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Completed Research PaperDocument14 paginiCompleted Research Paperapi-545708059Încă nu există evaluări

- Longer Analgesic Effect With Naproxen Sodium Than Ibuprofen in Post Surgical Dental Pain A Randomized Double Blind Placebo Controlled Single DoseDocument11 paginiLonger Analgesic Effect With Naproxen Sodium Than Ibuprofen in Post Surgical Dental Pain A Randomized Double Blind Placebo Controlled Single DoseAngélica María AponteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maxillary Lateral Incisor Injection Pain Using The Dentapen Electronic SyringeDocument5 paginiMaxillary Lateral Incisor Injection Pain Using The Dentapen Electronic SyringeKEY 1111Încă nu există evaluări

- Angle 2019 Effectiveness of Verbal Behavior Modification and Acetaminophen OnDocument7 paginiAngle 2019 Effectiveness of Verbal Behavior Modification and Acetaminophen OnTarif HamshoÎncă nu există evaluări

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument18 paginiNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptAkbarian NoorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shetty Et Al. 2008Document10 paginiShetty Et Al. 2008EmmanuelRajapandianÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Open Dentistry Journal: Methodologies in Orthodontic Pain Management: A ReviewDocument6 paginiThe Open Dentistry Journal: Methodologies in Orthodontic Pain Management: A Reviewnevin santhoshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sensação OrtognatiaDocument9 paginiSensação OrtognatiaKaren Viviana Noreña GiraldoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pain Management in ChildrenDocument9 paginiPain Management in ChildrenNASLY YERALDINE ZAPATA CATAÑOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oclusion 1Document10 paginiOclusion 1Itzel MarquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uri 2011Document5 paginiUri 2011anton.neonatusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Burn Pain and AnxietyDocument7 paginiBurn Pain and AnxietyywwonglpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pain Management in Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) ProtocolsDocument8 paginiPain Management in Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) ProtocolsbokobokobokanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sedation Practice Outside The Operating Room For Pediatric Gastrointestinal EndosDocument2 paginiSedation Practice Outside The Operating Room For Pediatric Gastrointestinal EndosAngeles ChÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6 E0 CCD 01Document4 pagini6 E0 CCD 01evytriutamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Endodontics: Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral PathologyDocument4 paginiEndodontics: Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral PathologyAline LonderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A SultanDocument7 paginiA SultanFernando MenesesÎncă nu există evaluări

- AnesDocument8 paginiAnesrachma30Încă nu există evaluări

- Quirinen EnglDocument7 paginiQuirinen EnglOctavian BoaruÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peri ImplantitisDocument21 paginiPeri ImplantitisStephanie PinedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Outcome After Regional Anaesthesia in The Ambulatory Setting Is It Really Worth It? 1Document13 paginiOutcome After Regional Anaesthesia in The Ambulatory Setting Is It Really Worth It? 1api-28080236Încă nu există evaluări

- Crew List September-2Document21 paginiCrew List September-2ajenggayatriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aerobic Exercise and Lipids and Lipoproteins in WomenDocument33 paginiAerobic Exercise and Lipids and Lipoproteins in WomenajenggayatriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Immunohistochemical Characterization of Rapid Dentin Formation Induced by Enamel Matrix DerivativeDocument11 paginiImmunohistochemical Characterization of Rapid Dentin Formation Induced by Enamel Matrix DerivativeajenggayatriÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Pharma and Bio Sciences: Research Article Human PhysiologyDocument6 paginiInternational Journal of Pharma and Bio Sciences: Research Article Human PhysiologyajenggayatriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Immunohistochemical Characterization of Rapid Dentin Formation Induced by Enamel Matrix DerivativeDocument11 paginiImmunohistochemical Characterization of Rapid Dentin Formation Induced by Enamel Matrix DerivativeajenggayatriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appa Et1Document4 paginiAppa Et1Maria Theresa Deluna MacairanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scheme of Work Writing Baby First TermDocument12 paginiScheme of Work Writing Baby First TermEmmy Senior Lucky100% (1)

- Role of ICT & Challenges in Disaster ManagementDocument13 paginiRole of ICT & Challenges in Disaster ManagementMohammad Ali100% (3)

- An Integrative Review of Relationships Between Discrimination and Asian American HealthDocument9 paginiAn Integrative Review of Relationships Between Discrimination and Asian American HealthAnonymous 9YumpUÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mcob OcDocument19 paginiMcob OcashisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Golden Rule ReferencingDocument48 paginiGolden Rule Referencingmia2908Încă nu există evaluări

- Pilot Test Evaluation Form - INSTRUCTORDocument9 paginiPilot Test Evaluation Form - INSTRUCTORKaylea NotarthomasÎncă nu există evaluări

- HUAWEI OCS Business Process Description PDFDocument228 paginiHUAWEI OCS Business Process Description PDFdidier_oÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kinetic - Sculpture FirstDocument3 paginiKinetic - Sculpture FirstLeoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chap 4 - Shallow Ult PDFDocument58 paginiChap 4 - Shallow Ult PDFChiến Lê100% (2)

- Yaskawa Product CatalogDocument417 paginiYaskawa Product CatalogSeby Andrei100% (1)

- Sample PREP-31 Standard Sample Preparation Package For Rock and Drill SamplesDocument1 paginăSample PREP-31 Standard Sample Preparation Package For Rock and Drill SampleshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Graham HoltDocument4 paginiGraham HoltTung NguyenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Newton's Three Law of MotionDocument6 paginiNewton's Three Law of MotionRey Bello MalicayÎncă nu există evaluări

- OP-COM Fault Codes PrintDocument2 paginiOP-COM Fault Codes Printtiponatis0% (1)

- Fun33 LCNVDocument6 paginiFun33 LCNVnehalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Second Form Mathematics Module 5Document48 paginiSecond Form Mathematics Module 5Chet AckÎncă nu există evaluări

- No Man Is An Island - Friendship LoyaltyDocument4 paginiNo Man Is An Island - Friendship LoyaltyBryanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Muhammad Adnan Sarwar: Work Experience SkillsDocument1 paginăMuhammad Adnan Sarwar: Work Experience Skillsmuhammad umairÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trading Psychology - A Non-Cynical Primer - by CryptoCred - MediumDocument1 paginăTrading Psychology - A Non-Cynical Primer - by CryptoCred - MediumSlavko GligorijevićÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Brief Tutorial On Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Sets and SystemsDocument10 paginiA Brief Tutorial On Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Sets and SystemstarekeeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hostel Survey Analysis ReportDocument10 paginiHostel Survey Analysis ReportMoosa NaseerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Researchpaper Parabolic Channel DesignDocument6 paginiResearchpaper Parabolic Channel DesignAnonymous EIjnKecu0JÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solution of Linear Systems of Equations in Matlab, Freemat, Octave and Scilab by WWW - Freemat.infoDocument4 paginiSolution of Linear Systems of Equations in Matlab, Freemat, Octave and Scilab by WWW - Freemat.inforodwellheadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mini Test PBD - SpeakingDocument4 paginiMini Test PBD - Speakinghe shaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sap 47n WF TablesDocument56 paginiSap 47n WF TablesjkfunmaityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 6 Team Zecca ReportDocument1 paginăWeek 6 Team Zecca Reportapi-31840819Încă nu există evaluări

- The Entrepreneurial Spirit From Schumpeter To Steve Jobs - by Joseph BelbrunoDocument6 paginiThe Entrepreneurial Spirit From Schumpeter To Steve Jobs - by Joseph Belbrunoschopniewit100% (1)

- Smart Meter For The IoT PDFDocument6 paginiSmart Meter For The IoT PDFNaga Santhoshi SrimanthulaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baird, A. Experimental and Numerical Study of U-Shape Flexural Plate.Document9 paginiBaird, A. Experimental and Numerical Study of U-Shape Flexural Plate.Susana Quevedo ReyÎncă nu există evaluări