Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

California Chief Justice Ronald George Leaves Historic Legacy - Los Angeles Times

Încărcat de

theplatinumlife73640 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

13 vizualizări3 paginiCalifornia's 27th chief justice will step down on midnight, Jan. 2. He will leave behind a court system that is vastly different from the one he inherited. Law professors and others expect him to have an enduring legacy.

Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentCalifornia's 27th chief justice will step down on midnight, Jan. 2. He will leave behind a court system that is vastly different from the one he inherited. Law professors and others expect him to have an enduring legacy.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

13 vizualizări3 paginiCalifornia Chief Justice Ronald George Leaves Historic Legacy - Los Angeles Times

Încărcat de

theplatinumlife7364California's 27th chief justice will step down on midnight, Jan. 2. He will leave behind a court system that is vastly different from the one he inherited. Law professors and others expect him to have an enduring legacy.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 3

Back to Original Article

California Chief Justice Ronald George leaves historic legacy

George will leave the state Supreme Court on Jan. 2. He consolidated municipal and superior courts and brought them under his

authority. He also wrote key decisions on abortion and same-sex marriage.

December 30, 2010 | By Maura Dolan, Los Angeles Times

Faced with the self-assigned task of writing the California Supreme Court's first ruling on gay marriage, Chief Justice Ronald M. George drafted an opinion in

early 2008 with two different endings. One gave same-sex couples the right to marry. The other didn't. Then he asked the six associate justices for reaction.

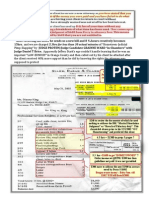

FOR THE RECORD:

Ronald George: An article in the Dec. 30 Section A about retiring Chief Justice Ronald M. George of the California Supreme Court incorrectly referred to the

"late" Sargent Shriver. Shriver, the father-in-law of former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, is alive.

George soon learned that his colleagues were split 3 to 3. His vote would decide the most burning civil rights question of the day.

George's handling of the marriage case was emblematic of his tenure as California's 27th chief justice. He was a centrist, the tie-breaker on the state high court,

but also willing to put his reputation on the line and do the unpredictable.

When he steps down on midnight, Jan. 2, after four decades as a pivotal player in California law, George will leave behind a court system that is vastly different

from the one he inherited. Law professors and others expect him to have an enduring legacy.

"He was the most extraordinary leader of the Supreme Court in modern history," said Treasurer Bill Lockyer, a Democrat and former legislator and attorney

general.

George, 70, took big risks as head of the California judiciary, consolidating courts and bringing them under his authority to turn the judicial branch into a

single, independent force. He created self-help services for people who could not afford lawyers. He insisted that courts have interpreters for the non-English

speaking. He wrote a 1996 abortion ruling that triggered a campaign to unseat him.

But the moderate Republican jurist was legally cautious, disinclined to take the law to new places. He was what one law professor called "a tinkerer." The

mostly Republican, relatively conservative court he headed is widely considered one of the most influential state Supreme Courts in the country, but was not

known for innovative legal thinking.

As a jurist George moved the court closer to the middle and stressed compromise. The dissent rate under George plummeted. His rulings were sound but

rarely soared, scholars said.

"He brought a lot of brainpower and political savvy to the position of chief justice," said Golden Gate Law School professor Peter Keane.

Immigrant parents

George grew up in Beverly Hills, the son of a Hungarian immigrant mother and French immigrant father. He was groomed for foreign affairs, but eventually

decided international diplomacy was not for him. Law school at Stanford University was a fall-back position. He wasn't sure what he wanted to do with his life.

He chose to practice law in government, eschewing the vastly higher pay of the private sector. He became a deputy attorney general, arguing before the U.S.

Supreme Court, a trial judge in Los Angeles County, an appeals court judge and finally an associate justice of the California Supreme Court. Former Gov. Pete

Wilson elevated him to chief justice in 1996.

Shortly after being elevated, the new chief justice went on the road, a state map and a yellow marker in his back pocket. He inspected the courts in all 58

counties and discovered that some were teetering.

He met a judge whose chambers was a converted broom closet. He found jurors sharing an entrance with manacled prisoners. He once had to cut a quick

check to keep a courthouse from closing.

Armed with his findings, he lobbied for and won state approval of a vast restructuring of the judiciary. More than 200 municipal and superior courts were

merged into a single trial court system, and 532 courthouses went from county to judicial-branch ownership.

George said justice should be equal from county to county. He wanted uniform policies and practices, and he figured the judiciary would have more clout in

Sacramento if it spoke with one voice.

Legal analysts consider the consolidation of the courts a historic achievement. George has received national recognition and awards for his work.

"It is a much more efficient system," said Santa Clara University law professor Gerald Uelmen, an analyst of California courts. "I think he will rank up there

as one of the most effective administrators the court has ever had."

George's critics, however, saw a power grab. The Administrative Office of the Courts, which now runs the court system, rapidly grew. Some trial judges

resented the loss of independence and derided the ballooning bureaucracy as wasteful. They dubbed him "King George."

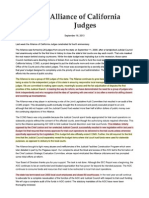

A group of dissenters formed the Alliance of California Judges. The membership is confidential, but the directors claim that more than 200 of the state's 1,700

judges belong.

Their aim is to restore more autonomy to the trial courts. They were particularly incensed when George decided to close courts one day a month for almost a

year rather than make other cuts.

Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Charles Horan, one of the founding members of the group, complained that George pursued a failed model of

judicial administration that "demanded centralized decision-making by an insular minority of loyalists, actively squelched dissent and greatly and

unacceptably diminished the role of the trial courts and trial judges in the management of the affairs of the judiciary."

George said such complaints were inevitable. When some judges critical of the consolidation suggested the powerful, policy-making Judicial Council be filled

with elected judges, rather than those selected by the chief, George declared that would be "a declaration of war."

"We really have created a judicial branch not just in name or theory but in reality," George said. "When I first went to Sacramento, I was asked which

agency I was with and who I reported to. I said, 'You don't get it. We are a separate, co-equal branch of government.' They all get that now."

When George stunned even his colleagues by announcing his retirement on July 14, he had in mind a successor who would keep intact the statewide system he

had built. He recommended Sacramento Court of Appeal Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye, saying she had the administrative and diplomatic skills and a "backbone

of steel" needed to deal with dissenting judges and a cash-strapped state.

Cantil-Sakauye, who is Filipina, will be the first non-white to serve as chief justice. George said he planned to spend his retirement traveling with his wife of 44

years, Barbara, spending time with their three adult sons and two granddaughters, and rereading the "great books." He does not intend to practice law.

Priced out of system

Soon after he was named chief justice, George discovered that the middle class as well as the poor had been priced out of the legal system. People with no legal

education were appearing in court alone on such vital matters as child custody, guardianship, elder abuse, domestic violence and housing disputes.

George wanted the state to provide such litigants with legal aid lawyers, but the budget crisis forced him to settle for a temporary, pilot project, which starts in

January. Even then, he had to resort to political wiles George described himself as "shameless" to get the governor's approval.

He told Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger the law would be named the Sargent Shriver Civil Counsel Law after Schwarzenegger's late father-in-law.

Under George's prodding, jury duty and jury instructions were revamped. He reported to jury duty four times as chief justice and changed the requirement for

duty to one day or one trial a year.

Relations between the statewide judiciary and the Legislature, frayed when George became chief, warmed.

His predecessor, Malcolm M. Lucas, had infuriated legislators with a ruling that upheld term limits. Lockyer, who was then a legislator, said many of his

colleagues thought Lucas "went out of his way to add gratuitous insult to the commentary."

"So Ron George had to clean up after the elephant," Lockyer said. "He restored relationships partly because he worked so hard and partly because he may be

the most diplomatic human being I have met. When I would try to provoke him, I couldn't."

George took command of cases that involved the Legislature or the governor, and when the court ruled against the other branches, he couched the losses in

language designed not to give offense.

"Incredibly effective," is how state Senate leader Darrell Steinberg described George. "He is not a partisan, and he doesn't go out of his way to poke you in the

eye. He is a pretty darn good country politician."

George spent long hours in Sacramento seeking legislative approval for court bills. One legislator said she decided to vote his way because she was

embarrassed to see the chief justice hanging in the hallway with the lobbyists.

George created a commission to promote judicial independence. The effort to oust him for writing an opinion that overturned a parental-consent abortion law

"sensitized him to the political vulnerability of judges," Uelmen said.

George's rulings favored a strong 1st Amendment and protection from discrimination for women and minorities, Uelmen said. He was considered conservative

on most law-and-order issues, although two of his three final rulings were for the defense.

When he took over, the court was viewed as anti-plaintiff, with business expected to win over consumers. The court is no longer so predictable.

But George was not viewed as a legal trailblazer.

"Maybe that is incompatible with being the centrist that he is," said UC Irvine Law School Dean Erwin Chemerinsky. "At a time when our society and legal

system is deeply divided, he was such a non-divisive figure."

Some scholars were dismayed by George's rulings on ballot measures. George has called for a reining in of the initiative process, which he views as increasingly

controlled by moneyed special interests. But as a jurist he was more deferential.

"There are all sorts of laws I might personally view as foolish that I am bound to uphold," he said. And then, tellingly, he added: "The court can't be viewed as

Copyright 2014 Los Angeles Times Terms of Service | Privacy Policy | Index by Date | Index by Keyword

flouting the people's will."

Conservatives say that is what he did in the court's May 15, 2008, gay marriage ruling. He had met with each justice individually and wrestled with Perez v.

Sharp, a 1948 California Supreme Court ruling that overturned a ban on interracial marriage and declared marriage a fundamental right.

"No matter which way we went," George said, "we had to cope with this law on the books."

After weeks of mulling the law and its effect on racial discrimination, George broke the tie. His decision not only gave gays the right to marry which voters

took away six months later with Proposition 8 but also bestowed the same legal protection from discrimination the law had long given race and gender. No

other state high court had afforded sexual orientation such constitutional status.

With his signature at the end of a 121-page ruling, the self-effacing jurist reputed for court administration left his most enduring stamp on the law and

California history.

maura.dolan@latimes.com

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- FBI Corruption San Diego - Gti NewsDocument9 paginiFBI Corruption San Diego - Gti Newstheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Gambling and MarxDocument4 paginiGambling and MarxJordan SpringerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nyerere Kuhusu Elimu - New PDFDocument180 paginiNyerere Kuhusu Elimu - New PDFedwinmasaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Network Sovereignty: Building The Internet Across Indian CountryDocument19 paginiNetwork Sovereignty: Building The Internet Across Indian CountryUniversity of Washington PressÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stuart Hall - Thatcherism (A New Stage)Document3 paginiStuart Hall - Thatcherism (A New Stage)CleoatwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spotlight On Commission On Judicial Performance PDFDocument78 paginiSpotlight On Commission On Judicial Performance PDFtheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Freedom of SpeechDocument1 paginăFreedom of Speechtheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Why The 2011 Elkin Commission Should MatterDocument1 paginăWhy The 2011 Elkin Commission Should Mattertheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Recent Proof of Prosecutorial Misconduct Mirrors OCDA's Bad Old Days - OC Weekly PDFDocument11 paginiRecent Proof of Prosecutorial Misconduct Mirrors OCDA's Bad Old Days - OC Weekly PDFtheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Rogues in Robes.Document7 paginiRogues in Robes.theplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Hometowning Stark by Brice and Ward in King Vs KingDocument46 paginiHometowning Stark by Brice and Ward in King Vs Kingtheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Court Ants... Alliance of California Judges and Associated "Malcontents and Insects" Beneath The Status of AntsDocument9 paginiCourt Ants... Alliance of California Judges and Associated "Malcontents and Insects" Beneath The Status of Antstheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- "Crime After Crime" Is Documentary About Deborah Peagler's Murder Conviction and The Campaign To Free HerDocument3 pagini"Crime After Crime" Is Documentary About Deborah Peagler's Murder Conviction and The Campaign To Free Hertheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Post Hometowning Jeff Stark - Bill RetaliationDocument4 paginiPost Hometowning Jeff Stark - Bill Retaliationtheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Knize Testimony DOJ Judicial Conference Bankruptcy CorruptionDocument6 paginiKnize Testimony DOJ Judicial Conference Bankruptcy Corruptiontheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Attorney Ethics RulesDocument2 paginiAttorney Ethics Rulestheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- The Sting California Judicial CommDocument7 paginiThe Sting California Judicial Commtheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Perjury and Lies by Judge Peter McBrien at the Commission on Judicial Performance: Whistleblower Leaked CJP Records Documenting False Statements and Perjurious Testimony by Hon. Peter J. McBrien Sacramento Superior Court - Judge Steve White - Judge Laurie Earl - Judge Robert Hight - Judge James Mize Sacramento County - California Supreme Court Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye, Justice Goodwin Liu, Justice Carol Corrigan, Justice Leondra Kruger, Justice Ming Chin, Justice Mariano-Florentino Cuellar, Kathryn Werdegar Supreme Court of CaliforniaDocument49 paginiPerjury and Lies by Judge Peter McBrien at the Commission on Judicial Performance: Whistleblower Leaked CJP Records Documenting False Statements and Perjurious Testimony by Hon. Peter J. McBrien Sacramento Superior Court - Judge Steve White - Judge Laurie Earl - Judge Robert Hight - Judge James Mize Sacramento County - California Supreme Court Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye, Justice Goodwin Liu, Justice Carol Corrigan, Justice Leondra Kruger, Justice Ming Chin, Justice Mariano-Florentino Cuellar, Kathryn Werdegar Supreme Court of CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jeff Stark's "Post Hometowning" Extortion BillDocument1 paginăJeff Stark's "Post Hometowning" Extortion Billtheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Gloria Allred King Vs King - DRAFTDocument42 paginiGloria Allred King Vs King - DRAFTtheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Freedom of Speech - 1ST Amendment - 1942Document2 paginiFreedom of Speech - 1ST Amendment - 1942theplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Judicial Misconduct 2014Document3 paginiJudicial Misconduct 2014theplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Chief Justice - 26.6m/with No 14th Amendment Protection NO LimosDocument16 paginiChief Justice - 26.6m/with No 14th Amendment Protection NO Limostheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- GrainneWard ElectionDocument2 paginiGrainneWard Electiontheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Federal Probation Journal - December 2011 - Lies, Liars, and Lie DetectionDocument9 paginiFederal Probation Journal - December 2011 - Lies, Liars, and Lie Detectiontheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Orange County Court Corruption - ProTem - Judge Grainne Ward - BriceDocument29 paginiOrange County Court Corruption - ProTem - Judge Grainne Ward - Bricetheplatinumlife7364100% (1)

- Alliance of California JudgesDocument2 paginiAlliance of California Judgestheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Fables of Wealth - NYTimesDocument3 paginiFables of Wealth - NYTimestheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- The Greatest Problem Faced by MankindDocument6 paginiThe Greatest Problem Faced by Mankindtheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court Forces Disputes From Court To Arbitration - A System With No Laws - SFGateDocument8 paginiSupreme Court Forces Disputes From Court To Arbitration - A System With No Laws - SFGatetheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Why The 2011 Elkin Commission Should MatterDocument1 paginăWhy The 2011 Elkin Commission Should Mattertheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- Understanding CPTSD 1Document10 paginiUnderstanding CPTSD 1V_Freeman100% (1)

- 2010.04.23 PR FrankPiersonToPen17DaysDocument2 pagini2010.04.23 PR FrankPiersonToPen17Daystheplatinumlife7364Încă nu există evaluări

- 2013 Board - of - Director Posting FINAL PDFDocument1 pagină2013 Board - of - Director Posting FINAL PDFlindsaywilliam9Încă nu există evaluări

- 1.1commerical History of ChinaDocument36 pagini1.1commerical History of ChinajizozorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Memorandum, Council's Authority To Settle A County Lawsuit (Sep. 16, 2019)Document7 paginiMemorandum, Council's Authority To Settle A County Lawsuit (Sep. 16, 2019)RHTÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appointment of Judges-Review of Constitutional ProvisionsDocument17 paginiAppointment of Judges-Review of Constitutional ProvisionsSAKSHI AGARWALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rizal's Madrid TourDocument8 paginiRizal's Madrid TourDrich ValenciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of MinistersDocument16 paginiList of MinistersNagma SuaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- EVS Sample Paper-3Document5 paginiEVS Sample Paper-3seeja bijuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annual Barangay Youth Investment Program 2019Document3 paginiAnnual Barangay Youth Investment Program 2019Kurt Texon JovenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Commonwealth of Nations: OriginsDocument2 paginiCommonwealth of Nations: OriginsAndaVacarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Etd613 20100131153916Document208 paginiEtd613 20100131153916Panayiota CharalambousÎncă nu există evaluări

- Universality of Human Rights by Monika Soni & Preeti SodhiDocument5 paginiUniversality of Human Rights by Monika Soni & Preeti SodhiDr. P.K. PandeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- A - STAT - AGUINALDO v. AQUINODocument2 paginiA - STAT - AGUINALDO v. AQUINOlml100% (1)

- GERIZAL Summative Assessment Aralin 3 - GROUP 4Document5 paginiGERIZAL Summative Assessment Aralin 3 - GROUP 4Jan Gavin GoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wa'AnkaDocument367 paginiWa'AnkaAsarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ireland and The Impacts of BrexitDocument62 paginiIreland and The Impacts of BrexitSeabanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rizal Leadership Tips from National HeroDocument2 paginiRizal Leadership Tips from National HeroJayson ManoÎncă nu există evaluări

- IOC President Tours AfricaDocument3 paginiIOC President Tours AfricabivegeleÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Is Masculinity Depicted in Romeo and JulietDocument1 paginăHow Is Masculinity Depicted in Romeo and JulietWatrmeloneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Religious Aspects of La ViolenciaDocument25 paginiReligious Aspects of La ViolenciaDavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- CWOPA Slry News 20110515 3500StateEmployeesEarnMoreThan100kDocument90 paginiCWOPA Slry News 20110515 3500StateEmployeesEarnMoreThan100kEHÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manichudar September 09 2012Document4 paginiManichudar September 09 2012muslimleaguetnÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Family ValuesDocument9 paginiList of Family ValuesTrisha Anne TorresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liputa' Are Sometimes Also Designed For Different Purposes, and Aimed atDocument12 paginiLiputa' Are Sometimes Also Designed For Different Purposes, and Aimed atBob SitswhentoldtostandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Samson OptionDocument5 paginiSamson OptionRubén PobleteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Youth Pledge Day Marks Birth of Indonesian NationDocument6 paginiYouth Pledge Day Marks Birth of Indonesian NationisnadewayantiÎncă nu există evaluări