Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Teachingforlearningassignment2 Essay

Încărcat de

api-256580150Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Teachingforlearningassignment2 Essay

Încărcat de

api-256580150Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

PaulStevens5Sep13

TeachingforLearningAssignment2Essay

Demonstrate your understanding of the learning needs of the adolescent.

Discuss how the ideas of four influential thinkers in education have contributed to your

understanding of how to create a positive learning environment for the adolescent learner.

How would you include these perspectives in your own teaching?

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Then, the whining schoolboy with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school.

- William Shakespeare, The Seven Ages of Man

The process of becoming a teacher involves a re-evaluation in how to approach even

basic interactions with people we deal with everyday. This is the student-teacher

relationship. An inherently strange one; a push and pull, giving and receiving; an

often reluctant exchange of knowledge, a power struggle. This enforced and often

uncomfortable alliance is complicated further, in the secondary school context, by one

of the players (or rather 25-35 of them in any given classroom) being adolescent (a

word which brings fear to the minds of many, even well-adjusted, adults). They are

struggling through that transitory time in all of our lives which no sane person over

20 would ever want to re-endure.

Coming to terms with this realignment had me thinking during my first practicum:

The simple, go-to, conversational topics of adults - the safe, small-talk questions we

ask on first meeting acquaintances: What do you do for a living?, Are you

married?, How many children do you have?; the pigeonholing queries to help us

suss out new people - seem inappropriate in getting to know adolescents in a

teaching environment.

The nature of adolescence is that it manifests itself not just in the gradual and drastic

physical changes of puberty - that take us unawares between ages 12 and 18, as we

watch our body change from one we have just barely become accustomed to into a

new and unusual hormonal frame which starts doing things parents or health class

hardly begin to prepare us for: pimples and growing pains, hair in strange places and

ID:10751581

PaulStevens5Sep13

flowings of blood, sexual urges and nightly self-abuse.

No, on top of this the adolescent must become. Become what? Well, that is perhaps the

ultimate question. One even many in their twenties struggle to answer (some never)

and a process that could be a full-time job, education aside, for those in their teens. To

put it obviously: Adolescence is a child becoming an adult. Sounds simple enough, but

this is no small feat and it rarely happens without pain, and the part that education

can play in this process is, quite literally, life-changing.

Lets paint a picture. For the purposes of this essay generalisation will be required.

There are as many adolescence (the period of life, plural) as there are people over a

certain age, but still a few broad statements can be made for the conveniences of

discussion.

If we put aside the physical transitions already hinted at, as complicating as they can

be for any young person, a few necessary points should be made specifically in regard

to internal changes, both psychological and emotional, to help us come to terms with

the unique requirements of the adolescent learner.

The adolescent is a creature of doubt. It is said that the main thing any young person

needs is to fit in. They desperately want to be liked by their peers and more often

than not they want anything but to stand out and will go to extraordinary lengths not

to look stupid. We cant take the impact of this self-consciousness for granted.

Their self-concept is still forming and their identity is in sometimes constant flux

(Fenstermacher & Soltis, 2004). The reason it can be so hard to get to know a teenager

is that very often they dont yet know themselves. As stated, it is normal to ask an

adult, if not in so many words, Who are you?. They will usually respond confidently

and enthusiastically (often even long-windedly, as all humans, as a generalisation, love

to talk about themselves). But ask the same question to the average young person and

at best they will reply with a convoluted non-answer. More commonly their answer

will consist of confused looks and grunts or single syllables. At worst their answer

will include cursing and open aggression at the insolence of such a stupid question.

Paradoxically, as well as wanting to fit in, the adolescent wants independence (Coleman,

ID:10751582

PaulStevens5Sep13

1996). They value making their own choices, even as they dont often know what they

should be, and a key part of the adolescent process is the forming of a functional

decision-making capacity. They want to be able to make mistakes, but they want to do

so (whether they realise it or not) in a safe environment. Added to this is the

contradictory attitude that many adults have in relation to the teenagers in their lives

(teachers and parents particularly) in that they want teenagers to have some degree

of independence, but also want to stop them making the same mistakes they did

(Coleman, 1996). We are happy with young people making their own choices as long

as they make the choice we want them to (perhaps the maxim that some things need

to be learnt the hard way would be a more appropriate approach).

This dichotomy is what makes secondary teaching so challenging and sometimes seem

close to impossible.

School for many adolescents is nothing but obligation. They do it because they

apparently must, with no other perceivable option available to them. It is too often

akin to the daily grind adults in jobs they hate suffer through: Looking busy avoiding

work, avoiding the boss, waiting impatiently for lunch, biding time until the weekend

and the next break from work and so on. The conveyer-belt, production-line mentality

of many education systems and schools could easily be mistaken for facilitating little

more than factories of compliant cookie-cutter workers to fuel a consumerist society,

which looks with suspicion on real creativity or anyone poking their head outside of

the box (Freire, 1970).

Schools: Too often institutions defined by boredom and obligation. Why would anyone

choose to be there? (And why the hell would anyone go back there to become a

teacher?! That least enviable of positions in too bureaucratic a framework.)

Educational researcher Sam Intrator (2003) describes a typical student he

encounters:

Like most of the students whom I came to know[at the school], Jeff was a young

man of deep passion and diverse interests. He was energetic, thoughtful and

playful. When I heard him talk about his dreams, fears, and hopes, he reminded

me of how complex the journey of adolescence is in todays world. He was hard

at work figuring himself out and learning to understand his place in his peer

group, his family, and the world. In his writing, thinking and conversations, he

ID:10751583

PaulStevens5Sep13

was trying on ideas and actively constructing a sense of self; yet his openness in

school to big ideas seemed to get shucked off like a backpack outside the

classroom. (pg. 21)

But it needn't be like this. Schools dont have to be the most regimented institutions

in our society, after prisons (Robinson, 2009). Education doesnt have to equal

conformity. Or kill creativity, as the educationalist Ken Robinson puts it.

Picking up from Howard Gardners foundational theory of multiple intelligences,

expounded in his seminal work Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences

(1983), where Garner explains the numerous fruitful ways in which we can

understand intelligence outside of a solely mathematical-logical/linguistic

understanding as promoted in standardised IQ tests, Ken Robinson has spent much of

his career rallying against what he sees as the destructive environment in many of

our schools, where, instead of promoting creativity and creative thinking, they too

often penalise it (Robinson, 2009).

The question arises: Should adolescents be forced to fit the current framework of

education, or should secondary education instead be created to fit the needs of the

adolescent learner? Unfortunately this is rarely the same thing.

Paulo Freire, progressive educationalist and the key proponent of a liberationist

approach to education, describes this system as a banking approach to education

(Freire, 1970). He recognises that teaching is a narrative discipline and that the

profession is suffering from, as he puts it, narration sickness (pg. 52).

The teacher talks about reality as if it were motionless, static, compartmentalised,

and predictable. Freire explains, Or else he expounds on a topic completely alien to

the existential experience of the students. His task is to fill the students with the

contents of his narration - contents which are detached from reality, disconnected

from the totality that engendered them and could give them significance. He

continues: Words are emptied of their concreteness and become a hollow, alienated,

and alienating verbosity (pg. 52). Freire sees this kind of teaching as playing a part

in oppression when instead education should be in the practice of liberation. He goes

so far as to see this banking approach as having a dehumanising function in which the

more meekly the receptacles permit themselves to be filled, the better students they

ID:10751584

PaulStevens5Sep13

are (pg. 53). He goes on to explain that, under this system, the scope of action

allowed to the students extends only as far as receiving, filing, and storing deposits,

and that ultimately, through this process, it is the people themselves who are filed

away through the lack of creativity, transformation, and knowledge in this (at best)

misguided system (pg. 53). Freire sees the traditional institutions of education as

complicit in removing agency from people, just as young people particularly are in

search of agency, and when it should be doing the exact opposite. His concept of

knowledge, vastly different from what he sees propagated under the banking

approach, is ideally one of invention and reinvention, emerging through the

restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world,

with the world, and with each other (pg. 53). His theory is that teaching and learning

should be an exciting journey of discovery for both the teacher and the learner, the

result of a deeply human engagement, and that ultimately the process should bring

learners to realise their own oppression and look to free themselves through

education itself. In this sense Paulo Freire advances a concept of education which is

inherently political, and inherently socialist.

Picking up from where Freire leaves off, the contemporary academic bell hooks (her

name is intentionally decapitalised) extends his thinking in her book Teaching to

Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (1994) to reflect on postcolonial

issues and the way that a liberationist approach can be used by feminist teachers to

undermine patriarchy. She proposes that for liberation to take place in the classroom

teachers need to be prepared to take the same risks they ask of their students. In my

classrooms, I do not expect students to take any risks that I would not take, to share in

any way that I would not share (pg. 21). She spells out her understanding of the role

that narrative, in a personal sense, can play in the teaching and learning experience:

When professors bring narratives of their experiences into classroom discussions it

eliminates the possibility that we [the teacher] can function as all-knowing, silent

interrogators. It is often productive if professors take the risk first, linking

confessional narratives to academic discussions so as to show how experience can

illuminate and enhance our understanding of academic material. But most professors

must practice being vulnerable in the classroom, being wholly present in mind, body,

ID:10751585

PaulStevens5Sep13

and spirit (pg. 21) (italics mine). I think this is key. To make the content of a

curriculum relevant the teacher must recognise the importance, not just of what the

students already knows, but the impact of their personal experience to enhance their

learning.

This idea comes straight from the pages of art theorist and educator John Dewey

(1938); perhaps the quintessential progressive educationalist, who detailed a

teaching philosophy based primarily on the concept of experience. He begins, much as

Freire does, by explaining two opposing educational theories: one the idea that

education is development from within, and the other that it is formation from

without (pg. 17). This is effectively traditional versus progressive educationalist

models. The traditional approach (similar to what Freire terms the banking concept)

being an understanding that it is the teachers role to impart knowledge to the

student who is basically an passive, empty vessel in need of tutelage. While the

progressive model, which Dewey proposes, is one where who the student is, what

they know, and, particularly, what they have experienced, is inherently relevant to

the teaching and learning process. He promotes a system where instead of

imposition from above there is instead the expression and cultivation of

individuality; to external discipline in opposed free activity; to learning from texts

and teachers [only], learning from experience (pg. 19). He explains how vital this

change in approach is in light of our changing world. As Ken Robinson explains, we no

longer know the jobs we are educating young people to be equipped for in the future

(Robinson, 2009). For this preparation to take place Dewey recognises that students

must be taught to make the most of the opportunities of present life, putting aside

static aims and materials (pg. 20). Experience, Dewey proposes, is key to preparing

young people. Each new experience has the ability to affect how future experiences

will affect an individual and so on. It is the teachers responsibility then to select the

kind of present experiences that live fruitfully and creatively in subsequent

experiences.

------------------------------------------------------------

This is then, if I may paint another picture, based on my understanding of these

ID:10751586

PaulStevens5Sep13

theorists, what I propose would be the ideal learning environment for the adolescent:

A classroom with a teacher who goes by their first name. Who opens up about who

they are, and expects their students to do the same. Who is honest when they have

made a mistake, and when a student impresses them with their insight. Who

regularly uses life experience to inform what goes on in the classroom. Who doesnt

shy away from asking big questions and letting their students do the same. A teacher

who expects much from their students and lets students expect much of them. Who

gets to know their students and sees them first as people. Who celebrates creativity

in all of its forms and knows that since much of the best art and literature come from

personal experience, so too should the way that it is taught, for content to be truly

understood. This is a classroom where assessment is not the reason to be there, but

instead a love of lifelong learning is promoted. Where assessment is instead more of

an afterthought, a requirement but not the primary guiding force behind the

enterprise. An environment where students opinions count for something and are

encouraged. A place where humour is welcome, where human connection takes place.

Where students can feel ok to fail, because that is often how we learn, but where they

get up again and are encouraged to always strive for more. A place where being

sidetracked can be ok, as long as its relevant to the liberation of students. A place

where passion for a subject and for learning itself is instilled. Where the struggles

and doubts of adolescence are not painted over or ignored, but instead incorporated in

the development of students learning. This is a place of structure with the aim of

being a place of freedom. A place where a process of doing and experiencing is seen as

relevant to the process of becoming.

In the first class I ever taught, a group of 11 girls learning Year 12 Art History, I

aimed to create an environment like this. The class had just begun looking at Modern

Art and I aimed to explain the project of Modernism as relevant to them in that it

formed the world we live in now, incorporating many of the ideas that we take for

granted. Being a girls school I saw it as necessary to include in my teaching an

understanding of the rights of women during the 19th-century to give context to the

world we live in now. Using artworks as the instigator for discussion I wanted them to

ask the big questions themselves that were motivated by the images. I encouraged

ID:10751587

PaulStevens5Sep13

them when this happened. I explained that art is more about asking questions than

demanding answers and that our experiences and opinions are relevant to how an

image is read. In one of my last classes we were looking at the women Impressionists,

Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot. I began the lesson with a contemporary artwork

from a feminist art collective which highlights the revealing disjuncture between

how prevalent representations of women are (in the nude particularly) compared

with how few women artists are represented in major collections of Modern Art. This

began a discussion about misogyny in art practice and in the art world and the way in

which art is a reflection, and sometimes an amplification, of the society in which it is

made. Many of the girls were not aware of the context of 19th-century sexism and

how quickly things have changed in society in regard to the rights and views of

women. I could tell the students were interested and that the art began to speak to

them in a relevant way they had not seen before. This was my aim. It was not just

about teaching the content but rather about enhancing their self-concept through

relevant material. Building new experiences for them through the curriculum.

Adolescence is hard enough. Why do we add to this struggle so often by making

young people learn things which are not relevant, or at least made relevant, to their

present lives? The features of adolescence include, as well as a sense of doubt and

self-consciousness, a curiosity about the world and a growing sense of their place in

it, and a new understanding of the nature of relationships. A great teacher should be

able to make use of these emerging aspects of self to educate young people and help

grow who they are. But for this to happen the secondary school teacher must show

authenticity. For teaching, and therefore learning, to be real, the teacher first has to

be real themself.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ID:10751588

PaulStevens5Sep13

References

Berger, J. (1973). Ways of Seeing. London, UK: Penguin Books.

Coleman, J. C. Adolescence in Moon B., & Mages A. S. (ed). (1996). Teaching and

Learning in the Secondary School. London, UK.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience & Education. New York, USA: Touchstone.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as Experience. New York, USA: Berkley Publishing Group.

Fenstermacher, G. D., & Solis, J. F. (2004). Approaches to Teaching (Fourth Edition). New

York, USA: Teachers College Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London, UK: Penguin Books.

Gardner, H. (1985). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York, USA:

Basic Books.

Intrator, S. M. (2003). Tuned in and Fired Up: How Teaching Can Inspire Real Learning in

the Classroom. USA: Yale University Press.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New

York, USA: Routledge.

Richardson, E. S. (1964). In the Early World: Discovering Art Through Crafts. New York,

USA: Pantheon Books.

Robinson, K. (2009). The Element: How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything. New

York, USA: Penguin Books.

ID:10751589

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Notes From A Small School: Articles From CFL Newsletters 2005 - 2014Document58 paginiNotes From A Small School: Articles From CFL Newsletters 2005 - 2014Zeus GhoshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preparing for the Journey Through Adolescence: A Handbook for TeensDe la EverandPreparing for the Journey Through Adolescence: A Handbook for TeensÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review of The LiteratureDocument13 paginiReview of The Literatureslytle23Încă nu există evaluări

- The Path to Purpose: Helping Our Children Find Their Calling in LifeDe la EverandThe Path to Purpose: Helping Our Children Find Their Calling in LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (8)

- Running Head: Diversity Statement of Informed Beliefs EssayDocument8 paginiRunning Head: Diversity Statement of Informed Beliefs Essayapi-355623191Încă nu există evaluări

- Erikson's Theory of Personality by Saher Hiba Khan (20185826) (Dept. of English)Document3 paginiErikson's Theory of Personality by Saher Hiba Khan (20185826) (Dept. of English)Saher Hiba KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Challenges of Middle and Late AdolescenceDocument3 paginiChallenges of Middle and Late AdolescenceEmpress AhnÎncă nu există evaluări

- What It Means To Grow Up - A Guide In Understanding The Development Of CharacterDe la EverandWhat It Means To Grow Up - A Guide In Understanding The Development Of CharacterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Freedom and BeyondDocument151 paginiFreedom and Beyondanto.a.fÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teenager Tales : An Attempt to Bridge the Gap Between Generations - Volume Two (Teen Talks Series Book 2)De la EverandTeenager Tales : An Attempt to Bridge the Gap Between Generations - Volume Two (Teen Talks Series Book 2)Încă nu există evaluări

- The Developmental Stages of Erik EriksonDocument7 paginiThe Developmental Stages of Erik EriksonSuha JamilÎncă nu există evaluări

- AdolescenceDocument48 paginiAdolescencekate kimeridzeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Developmental Tasks of Normal AdolescenceDocument5 paginiDevelopmental Tasks of Normal AdolescenceTrang Uyên NhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Embers :: Igniting Academic Excellence in Low Performing StudentsDe la EverandHidden Embers :: Igniting Academic Excellence in Low Performing StudentsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning To Learn: A Key Goal in A 21st Century CurriculumDocument2 paginiLearning To Learn: A Key Goal in A 21st Century CurriculumUK YouthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Forget School: Why young people are succeeding on their own terms and what schools can do to avoid being left behindDe la EverandForget School: Why young people are succeeding on their own terms and what schools can do to avoid being left behindÎncă nu există evaluări

- MPC-002 - 2020Document14 paginiMPC-002 - 2020Rajni KumariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leaving School and Starting Work: The Commonwealth and International Library: Problems and Progress in DevelopmentDe la EverandLeaving School and Starting Work: The Commonwealth and International Library: Problems and Progress in DevelopmentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stallion SenseDocument3 paginiStallion Senseapi-26021606Încă nu există evaluări

- A Quest for Knowledge and WisdomDocument5 paginiA Quest for Knowledge and WisdomVinze AgarcioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reflection On Erik Erikson Stages of DevelopmentDocument5 paginiReflection On Erik Erikson Stages of DevelopmentFeby DemellitesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preparing Today's Youth For Tomorrow's WorldDocument2 paginiPreparing Today's Youth For Tomorrow's WorldGenelen SapitulaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Excerpted from "Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain" by Daniel Siegel. Copyright © 2013 by Daniel Siegel. Excerpted by permission of Tarcher. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.Document9 paginiExcerpted from "Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain" by Daniel Siegel. Copyright © 2013 by Daniel Siegel. Excerpted by permission of Tarcher. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.wamu885100% (1)

- The Half-Baked Teen Brain: A Hazard or A Virtue?: Maia SzalavitzDocument2 paginiThe Half-Baked Teen Brain: A Hazard or A Virtue?: Maia SzalavitzNiftyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Teenagers Guide To Opting Out Not Dropping Out of SchoolDocument47 paginiThe Teenagers Guide To Opting Out Not Dropping Out of SchoolLisa NielsenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Humanities-Study of Adolescence - Manpreet KaurDocument20 paginiHumanities-Study of Adolescence - Manpreet KaurImpact JournalsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper About Teenage LifeDocument7 paginiResearch Paper About Teenage Lifeegja0g11100% (1)

- Summer PaperDocument7 paginiSummer Paperapi-433549002Încă nu există evaluări

- 8 Stages of Human DevelopmentDocument4 pagini8 Stages of Human DevelopmentJeepee John100% (4)

- Human Growth and Development TheoriesDocument13 paginiHuman Growth and Development TheoriesCatalina Ioana MutiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stages of Human Development by Erik Erikson and Four Personality Types Merill-Reid ModelDocument11 paginiStages of Human Development by Erik Erikson and Four Personality Types Merill-Reid ModelFrich Delos Santos PeñaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Developmental Stages of Erik EriksonDocument15 paginiThe Developmental Stages of Erik EriksonDee Lumayag100% (9)

- Human Growth and DevelopmentDocument64 paginiHuman Growth and DevelopmentmargauxeÎncă nu există evaluări

- PSYCHOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF ADOLESCENCEDocument11 paginiPSYCHOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF ADOLESCENCEdjrao81Încă nu există evaluări

- Skinner, B. F. (1973) .The Free and Happy StudentDocument6 paginiSkinner, B. F. (1973) .The Free and Happy StudentRaphael GuimarãesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roll Number:: Umar AliDocument5 paginiRoll Number:: Umar AliDil NawazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classroom ManagementDocument3 paginiClassroom Managementapi-334511924Încă nu există evaluări

- Self EsteemDocument24 paginiSelf EsteemChaloemporn ChantongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intrinsicmotivationamong Students Andteachers P Aper by Sandhyagatti N Ovember 8, 2 0 1 0Document20 paginiIntrinsicmotivationamong Students Andteachers P Aper by Sandhyagatti N Ovember 8, 2 0 1 0ShaziaÎncă nu există evaluări

- NEW ERA UNIVERSITY RESEARCH ASSIGNMENT COVERS TEEN DEVELOPMENTDocument11 paginiNEW ERA UNIVERSITY RESEARCH ASSIGNMENT COVERS TEEN DEVELOPMENTWillem James Faustino LumbangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essay On Puberty RealDocument2 paginiEssay On Puberty Realchin ongtangcoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hurried ChildDocument9 paginiThe Hurried ChildLucas Lima de SousaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Developmental TaskDocument45 paginiDevelopmental Taskmaria luzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Erikson's Stages of Life: Trust, Autonomy, Initiative and 8 MoreDocument3 paginiErikson's Stages of Life: Trust, Autonomy, Initiative and 8 Morezar aperoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Buagas Isagani Roy - Untitled DocumentDocument6 paginiBuagas Isagani Roy - Untitled DocumentIsagani Roy BuagasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 1 Knowing OneselfDocument24 paginiLesson 1 Knowing OneselfCleto Lustan Dometita Jr.Încă nu există evaluări

- Brief Description or Background of Present's Illness.Document9 paginiBrief Description or Background of Present's Illness.DianneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teenage, The Most Confusing Stage of LifeDocument3 paginiTeenage, The Most Confusing Stage of LifeMoniba MehbubÎncă nu există evaluări

- Development of Adolescence (The Adolescence)Document5 paginiDevelopment of Adolescence (The Adolescence)Nhật PhươngÎncă nu există evaluări

- Erik Erikson's Theory of Development: A Teacher's ObservationsDocument5 paginiErik Erikson's Theory of Development: A Teacher's ObservationsJoshua BugaoisanÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Hungarian-American Psychologist NamedDocument6 paginiA Hungarian-American Psychologist NamedMonique Clarivel Malalis LlamisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Task AdolescentsDocument3 paginiTask AdolescentsFinal MudrawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ed 1 - Article FinalsDocument6 paginiEd 1 - Article FinalsMonique Clarivel Malalis LlamisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reasons Behind TheDocument19 paginiReasons Behind Theanobanggustomo100% (1)

- Perdev ReportDocument36 paginiPerdev Reportpedreraxian1997Încă nu există evaluări

- Paulstevens-Cvapr14art 1Document3 paginiPaulstevens-Cvapr14art 1api-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Myteachingphilosophyjune 2014Document1 paginăMyteachingphilosophyjune 2014api-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Wscyear13arthistoryexampaper 3 CompressedDocument5 paginiWscyear13arthistoryexampaper 3 Compressedapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- 5 Unitplan-Explanation-DiverselearnersDocument8 pagini5 Unitplan-Explanation-Diverselearnersapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Signed Teachers Council Ethics StatementDocument1 paginăSigned Teachers Council Ethics Statementapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- p4 - Slides - Yr 13 Art History 5 - Exam Prep 1Document12 paginip4 - Slides - Yr 13 Art History 5 - Exam Prep 1api-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- p2 Reflection1Document2 paginip2 Reflection1api-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- p3 - at ReportsDocument5 paginip3 - at Reportsapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Year9sosresource BirthofchristianityDocument3 paginiYear9sosresource Birthofchristianityapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- 5 Unitplan-Explanation-MaoristudentsDocument4 pagini5 Unitplan-Explanation-Maoristudentsapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Teachingasinquiry EssayDocument10 paginiTeachingasinquiry Essayapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- 2013atreport 1-Signed 1Document4 pagini2013atreport 1-Signed 1api-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- p3 Lessonplanyear10sos1 FisheriesDocument3 paginip3 Lessonplanyear10sos1 Fisheriesapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Im Local Queer Trans 101 Comic - WebDocument12 paginiIm Local Queer Trans 101 Comic - Webapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Lessonplanyear10art1 ThelanguageofartDocument3 paginiLessonplanyear10art1 Thelanguageofartapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- p2 Lessonplanyear9art1 GridintropracticeDocument4 paginip2 Lessonplanyear9art1 Gridintropracticeapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Developingthecurriculuminsocietyassignment1 EssayDocument13 paginiDevelopingthecurriculuminsocietyassignment1 Essayapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Arthistory Abughraibseminarwrite UpDocument20 paginiArthistory Abughraibseminarwrite Upapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Mihi 1Document1 paginăMihi 1api-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Teachingasinquiry-Poster 1compressedDocument1 paginăTeachingasinquiry-Poster 1compressedapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- 1 Unitplan-CoversheetDocument4 pagini1 Unitplan-Coversheetapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Assessingstudentlearningassignment2 DiscussionexplanationDocument10 paginiAssessingstudentlearningassignment2 Discussionexplanationapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Unitplan ExplanationoneallearnersDocument4 paginiUnitplan Explanationoneallearnersapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- 5 Unitplan-Explanation-PedagogyDocument5 pagini5 Unitplan-Explanation-Pedagogyapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- 2 Unitplan-LessonoutlineDocument13 pagini2 Unitplan-Lessonoutlineapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- 5 Unitplan-Explanation-CurriculumDocument6 pagini5 Unitplan-Explanation-Curriculumapi-256580150Încă nu există evaluări

- Charge Nurse GuidelinesDocument97 paginiCharge Nurse GuidelinesLeofe Corregidor100% (1)

- Strengthening School-Community Bonds Through Administrative LeadershipDocument12 paginiStrengthening School-Community Bonds Through Administrative Leadershipnio_naldoza2489100% (2)

- Week 2 EIM 12 Q1 Indoyon Evaluated ESDocument8 paginiWeek 2 EIM 12 Q1 Indoyon Evaluated ESMarino L. SanoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit Plan Grade 6 Social StudiesDocument2 paginiUnit Plan Grade 6 Social Studiesapi-214642370Încă nu există evaluări

- The Effects of Blended Learning To Students SpeakDocument15 paginiThe Effects of Blended Learning To Students SpeakCJ PeligrinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pakistani TestsDocument5 paginiPakistani TestsHaleema BuTt100% (1)

- Human Development Research and StagesDocument9 paginiHuman Development Research and StagesJomelyd AlcantaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sasha Lesson PlanDocument2 paginiSasha Lesson Planapi-307358504Încă nu există evaluări

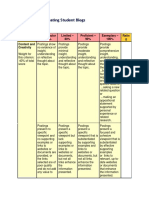

- A Rubric For Evaluating Student BlogsDocument5 paginiA Rubric For Evaluating Student Blogsmichelle garbinÎncă nu există evaluări

- P6 - The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices On Employees' Turnover IntentionDocument13 paginiP6 - The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices On Employees' Turnover IntentionI-sha ShahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mathematics-guide-for-use-from-September-2020 January-2021Document63 paginiMathematics-guide-for-use-from-September-2020 January-2021krisnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Data Analysis and MiningDocument23 paginiIntroduction To Data Analysis and MiningAditya MehtaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Art of Training (Your Animal) - Steve MartinDocument6 paginiThe Art of Training (Your Animal) - Steve MartinBlackDawnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Training and DevelopmentDocument15 paginiTraining and Developmentmarylynatimango135100% (1)

- Personal Development Module 4 Q1Document17 paginiPersonal Development Module 4 Q1Jay IsorenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Read The Following Passage and Mark The Letter A, B, C, or D To Indicate The Correct Answer To Each of The QuestionsDocument7 paginiRead The Following Passage and Mark The Letter A, B, C, or D To Indicate The Correct Answer To Each of The QuestionsHồng NhungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interjections in Taiwan Mandarin: Myrthe KroonDocument56 paginiInterjections in Taiwan Mandarin: Myrthe KroonRaoul ZamponiÎncă nu există evaluări

- M and E SEPSDocument3 paginiM and E SEPSIvy Joy TorresÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Different Types of Speech Context and Speech StyleDocument2 paginiThe Different Types of Speech Context and Speech StyleaquelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper 1: Organization & Management Fundamentals - Syllabus 2008 Evolution of Management ThoughtDocument27 paginiPaper 1: Organization & Management Fundamentals - Syllabus 2008 Evolution of Management ThoughtSoumya BanerjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course Syllabus English B2Document8 paginiCourse Syllabus English B2Ale RomeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- IDO Invitation LetterDocument1 paginăIDO Invitation LetterthepoliceisafteryouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gerwin Dc. ReyesDocument1 paginăGerwin Dc. ReyesInternational Intellectual Online PublicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Identifying and Selecting Curriculum MaterialsDocument23 paginiIdentifying and Selecting Curriculum MaterialsCabral MarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notre Dame of Masiag, Inc.: Unit Learning PlanDocument3 paginiNotre Dame of Masiag, Inc.: Unit Learning PlanGjc ObuyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uncertainty Environments and Game Theory SolutionsDocument10 paginiUncertainty Environments and Game Theory Solutionsjesica poloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Visionary CompassDocument77 paginiVisionary CompassAyobami FelixÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2018 Com Module 1 and 2Document6 pagini2018 Com Module 1 and 2Anisha BassieÎncă nu există evaluări

- CE 211: Plane Surveying: Module 1 - Importance and Principles of SurveyingDocument3 paginiCE 211: Plane Surveying: Module 1 - Importance and Principles of SurveyingMike Anjielo FajardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- K-12 Araling PanlipunanDocument32 paginiK-12 Araling PanlipunanJohkas BautistaÎncă nu există evaluări