Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Hirsutism: Clinical Practice

Încărcat de

Anonymous kltUTaTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Hirsutism: Clinical Practice

Încărcat de

Anonymous kltUTaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

clinical practice

The

new england journal

of

medicine

n engl j med

353;24

www.nejm.org december

15, 2005

2578

This

Journal

feature begins with a case vignette highlighting a common clinical problem.

Evidence supporting various strategies is then presented, followed by a review of formal guidelines,

when they exist. The article ends with the authors clinical recommendations.

Hirsutism

Robert L. Rosenfield, M.D.

From the Department of Pediatrics and

Medicine, University of Chicago, Pritzker

School of Medicine, Chicago. Address re-

print requests to Dr. Rosenfield at the

Department of Pediatrics and Medicine,

University of Chicago, Pritzker School of

Medicine, Section of Pediatric Endocrinology,

5841 S. Maryland Ave., MC-5053, Chicago, IL

60637, or at robros@peds.bsd.uchicago.edu.

N Engl J Med 2005;353:2578-88.

Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society.

A 19-year-old woman seeks care for slowly progressive hair growth. Since high school,

she has shaved her upper lip weekly and waxed her abdomen and thighs monthly. Her

menstrual periods are regular. Physical examination is unremarkable except for a body-

mass index (the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters) of

31 and trace hair over the abdomen and thighs, with a moderate amount over her back.

There is no clitorimegaly. How should this patient be evaluated and treated?

Physicians impressions about hirsutism range from considering it simply a cosmetic

problem to assuming it is de facto evidence of excess androgen. The truth lies some-

where in between. Although unwanted hair is often due to an ethnic or familial trait,

about half the cases of hirsutism are due to hyperandrogenism.

Hirsutism is defined medically as excessive terminal hair that appears in a male pat-

tern (i.e., sexual hair) in women.

1,2

About 5 percent of women of reproductive age in

the general population are hirsute, as indicated by a score of 8 or more on the Ferri-

manGallwey scale, which quantitates the extent of hair growth in the most androgen-

sensitive sites (Fig. 1 and 2).

3,4

However, this scoring system has limitations, particularly

because of the subjective nature of the assessment, which is especially problematic in

evaluating women who have blond hair or have had cosmetic treatment. The scale also

does not include the sideburn, perineal, or buttocks areas. Moreover, substantial hir-

sutism may exist in one or two areas without yielding a high score.

pathogenesis

The growth of sexual hair is entirely dependent on the presence of androgen (Fig. 3).

1,5

Before puberty, hair is vellus (small, straight, and fair), and the sebaceous glands in an-

drogen-sensitive follicles are small. In response to the increased levels of androgens at

puberty, vellus follicles in specific areas develop into terminal hairs (larger, curlier, and

darker, hence more visible), becoming sexual-hair follicles; higher androgen levels are

required for the growth of beard than for the growth of pubic and axillary hair. In other

areas (e.g., the forehead and cheeks), the increased androgen levels dramatically in-

crease the size of the sebaceous glands, but the hair remains vellus; the reason for this

differential response is unclear.

Hirsutism results from an interaction between the androgen level and the sensitivity

of the hair follicle to androgen. Most women with androgen levels that are twice the

upper limit of the normal range or higher have some degree of hirsutism.

6

However,

the severity of hirsutism does not correlate well with the level of androgen, because the re-

sponse of the androgen-dependent follicle to androgen excess varies considerably

within and among persons. Some women with excess androgen have no skin manifes-

tations, or they may have seborrhea, acne, or alopecia without hirsutism. In other wom-

the clinical problem

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by hani amalia on June 3, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med

353;24

www.nejm.org december

15, 2005

clinical practice

2579

F

i

g

u

r

e

1

.

T

h

e

F

e

r

r

i

m

a

n

G

a

l

l

w

e

y

S

c

o

r

i

n

g

S

y

s

t

e

m

f

o

r

H

i

r

s

u

t

i

s

m

.

E

a

c

h

o

f

t

h

e

n

i

n

e

b

o

d

y

a

r

e

a

s

m

o

s

t

s

e

n

s

i

t

i

v

e

t

o

a

n

d

r

o

g

e

n

i

s

a

s

s

i

g

n

e

d

a

s

c

o

r

e

,

f

r

o

m

0

(

n

o

h

a

i

r

)

t

o

4

(

f

r

a

n

k

l

y

v

i

r

i

l

e

)

,

a

n

d

t

h

e

s

e

a

r

e

s

u

m

m

e

d

t

o

p

r

o

v

i

d

e

a

h

o

r

m

o

n

a

l

h

i

r

s

u

t

i

s

m

s

c

o

r

e

.

(

A

d

a

p

t

e

d

f

r

o

m

H

a

t

c

h

e

t

a

l

.

3

)

1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by hani amalia on June 3, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med

353;24

www.nejm.org december

15

,

2005

The

new england journal

of

medicine

2580

en, hirsutism develops without the presence of ex-

cess androgen (termed idiopathic hirsutism).

Testosterone is the key circulating androgen.

6-9

It arises as a by-product of ovarian and adrenal func-

tion, either by secretion or by the metabolism of se-

creted prohormones (mainly androstenedione or

dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate) in peripheral tis-

sues, such as fat.

3,10

Testosterone levels during the

midfollicular phase of the menstrual cycle vary by

about 25 percent above and below the mean and

are highest in the early morning; levels are slightly

lower in the premenstrual phase and slightly high-

er in midcycle.

11

Free testosterone seems to be the main bioac-

tive portion of plasma testosterone.

12,13

The level

of free testosterone is often elevated when the to-

tal testosterone level is normal in hirsute women.

This reflects the relatively low levels of sex hor-

monebinding globulin in such women, which de-

termines the fraction of plasma testosterone that is

free or bound to albumin.

14

The levels of sex hor-

monebinding globulin are suppressed by the hy-

perinsulinemia of insulin resistance and by andro-

gen excess itself,

12,15

so that the total testosterone

level may be normal despite excess androgen levels.

The level of sex hormonebinding globulin is also

low in persons with hypothyroidism; rarely, it is

congenitally absent.

16

differential diagnosis

Hirsutism must be distinguished from hypertri-

chosis generalized excessive hair growth that

occurs as the result of either heredity or the use of

medications such as glucocorticoids, phenytoins,

minoxidil, or cyclosporine. Hypertrichosis, in which

hair is distributed in a generalized, nonsexual pat-

tern, is not caused by excess androgen (although

hyperandrogenism may aggravate this condition).

Approximately half of women with mild hir-

sutism (i.e., hirsutism with a score of 8 to 15, out

of a maximum of 36, on the FerrimanGallwey

scale) have the idiopathic condition,

6

whereas in

the remainder of these women and in most of those

with more marked hirsutism, androgen levels are

elevated. Hyperandrogenism is most often caused

by the polycystic ovary syndrome.

9,17

As discussed

in a recent review article,

18

this diagnosis is made

when there is otherwise unexplained chronic hy-

perandrogenism and oligo-ovulation or anovula-

tion.

19

Documentation of polycystic ovaries is not

necessary for the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syn-

drome but is a criterion for it if evidence of anovu-

lation is lacking.

20,21

About half of the cases are

nonclassic they lack some of the features classi-

cally associated with the syndrome (such as men-

strual irregularity, polycystic ovaries, or obesity)

18,22

and thus the absence of some such features in a

hirsute woman does not rule out the diagnosis.

Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with infer-

tility and insulin resistance (manifested as diabetes

mellitus or the metabolic syndrome a variably

expressed cluster of findings, including central obe-

sity, hypertension, glucose abnormalities, and dys-

lipidemia),

23

and possibly with an increased risk of

endometrial cancer.

18,20

Other causes of androgen excess occur infre-

strategies and evidence

Figure 2. Varying Degrees of Hirsutism.

Panel A demonstrates hirsutism with a FerrimanGall-

wey score of 1 for the lip and 4 for the chin. In Panel B,

the score is 3 to 4 for the lip and 3 for the chin. Photo-

graphs courtesy of Dr. David Ehrmann.

A

B

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by hani amalia on June 3, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med

353;24

www.nejm.org december

15, 2005

clinical practice

2581

quently. Nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia

is present in only 1.5 to 2.5 percent of women with

hyperandrogenism.

9,17

Androgen-secreting tumors

are present in about 0.2 percent of women with

hyperandrogenism

9

; more than half of such tumors

are malignant.

24

Cushings syndrome, hyperpro-

lactinemia, acromegaly, and thyroid dysfunction

must be considered as causes of androgen excess,

but these conditions usually present because of

symptoms other than hirsutism. About 8 percent

of women with hirsutism have mild, often asymp-

tomatic, idiopathic hyperandrogenism.

17

This con-

dition may be due to abnormal peripheral metabo-

lism of prohormones. Androgenic medications also

may cause hirsutism.

diagnostic strategies

The medical history and physical examination

should address risk factors associated with viriliz-

ing disorders, polycystic ovary syndrome or other

endocrinopathies, and the use of androgenic med-

ications. A rapid pace of development or progres-

Figure 3. Role of Androgen in the Development of Pilosebaceous Units.

In some areas of the skin, pilosebaceous units respond to androgen by forming sexual-hair follicles, whereas in other

areas these units respond by forming sebaceous glands. In balding scalp, under the influence of androgen, terminal

hairs not previously dependent on androgen very gradually revert to vellus-like hairs. Arrows indicate the effects of an-

drogens; antiandrogens variably reverse these processes. Hairs are depicted only in the anagen (growing) phase of their

growth cycle. (Adapted from Deplewski and Rosenfield.

1

)

Dermal

papilla

Sebaceous

gland

Vellus hair

Arrector

pili muscle

Androgen

Androgen

Vellus-like follicle

Prepubertal vellus follicle

Sebaceous follicle

(adult sebaceous gland)

Terminal hair follicle

Sexual hair

Balding scalp

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by hani amalia on June 3, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med

353;24

www.nejm.org december

15

,

2005

The

new england journal

of

medicine

2582

sion of hirsutism or evidence of virilization (such

as clitorimegaly or increasing muscularity) should

raise concern that an androgen-secreting neo-

plasm is present. However, tumors producing only

moderately excessive levels of androgen have indo-

lent presentations.

24,25

The high frequency of polycystic ovary syndrome

as a cause of hirsutism warrants attention to evi-

dence of anovulation (such as menstrual irregular-

ity), obesity, the metabolic syndrome, or insulin

resistance (such as the presence of acanthosis ni-

gricans or a family history of type 2 diabetes melli-

tus). If risk factors such as menstrual irregularity

are present, even normal degrees of unwanted hair

growth are usually associated with androgen ex-

cess.

26

The history is particularly important in as-

certaining whether androgenic drugs have been

used, since most such drugs are not detected by tes-

tosterone assays, with the exception of valproic acid,

which raises plasma testosterone levels.

27

The laboratory evaluation for hirsutism var-

ies among specialists, and the effect of various

approaches on outcomes is uncertain. Figure 4 il-

lustrates a practical approach.

If hirsutism is mild (i.e., with a FerrimanGall-

wey score of 8 to 15) and menses are regular, with

none of the features described above to suggest a

secondary cause, it is reasonable to forgo laborato-

ry evaluation, given the very high likelihood that

the hirsutism is idiopathic. (Historically, hirsutism

in women with regular periods was termed idio-

pathic hirsutism, but this group of cases encom-

passes idiopathic hyperandrogenism and nonclas-

sic or atypical polycystic ovary syndrome.

2,6,17,28,29

)

If hirsutism is moderate or severe (with a score of

more than 15) or there are features to suggest a

secondary cause, assessment of androgen levels is

prudent. Ultrasonographic examination of the ova-

ries, the adrenal glands, or both is a useful screening

procedure if the symptoms suggest the presence of

a neoplasm

30

; pelvic ultrasonography may be use-

ful if polycystic ovary syndrome is suspected.

20,21

Determinations of androgen levels are most ac-

curately performed by a specialty laboratory.

31

The

normal upper limit for total plasma testosterone

levels in women varies from about 70 to 90 ng per

deciliter (2.43 to 3.12 nmol per liter). This is because

there are systematic differences among assays,

32

and many laboratories provide excessively broad nor-

mal ranges because the general population includes

women with unrecognized androgen excess.

28,33

Testing for plasma free testosterone is 50 per-

cent more sensitive than that for total testosterone

in detecting androgen excess and is the best single

indicator of hyperandrogenism. However, there is

no uniform laboratory standard for measuring free

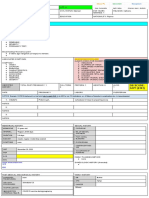

Figure 4 (facing page). Algorithm for the Initial Evalua-

tion of Hirsutism.

Risk assessment includes more than evaluating the de-

gree of hirsutism. Medications that cause hirsutism in-

clude anabolic or androgenic steroids (whether these

drugs have been used by athletes and patients with en-

dometriosis or sexual dysfunction should be consid-

ered). If hirsutism is moderate or severe or if risk factors

for underlying disorders (as shown) are present, andro-

gen excess must be ruled out. Assessment of the plasma

free testosterone level in the early morning (ideally, on

days 4 to 10 of the menstrual cycle in cycling women)

the time for which norms are standardized is the most

sensitive measure. However, a level that is measured at

random usually suffices, and a total testosterone level is

reasonable to consider if reliable assessment of free tes-

tosterone is not readily available. A normal total testos-

terone level supports the diagnosis of idiopathic hirsutism,

although a normal level does not rule out androgen ex-

cess. An early-morning plasma free testosterone level,

as determined by a specialty laboratory, is indicated if the

total testosterone level is marginally elevated (i.e., within

about 20 ng per deciliter [0.69 nmol per liter] of the upper

limit of normal), if the response to cosmetic therapy is

unsatisfactory, or if features suggestive of other disorders

emerge. An elevated plasma free testosterone level is an

indication for endocrinologic evaluation to determine

the cause. Other disorders to be considered, as shown,

include neoplasm and various endocrinopathies. Poly-

cystic ovary syndrome is the most common. Cushings

syndrome is suggested by the development of truncal

obesity, moon face, buffalo hump, purple striae, or prox-

imal muscle weakness; virilizing congenital adrenal hy-

perplasia or polycystic ovary syndrome by the premature

growth of pubic hair; hyperprolactinemia by the presence

of galactorrhea; and acromegaly by the coarsening of fa-

cial features or by hand enlargement. Additional testing

may include a pregnancy test (if the patient has amenor-

rhea), pelvic ultrasonography (if an ovarian neoplasm or

polycystic ovary syndrome is suspected), and measure-

ment of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and early-morn-

ing levels of 17

a

-hydroxyprogesterone (if congenital

adrenal hyperplasia or adrenal neoplasm is suspected).

Further workup typically begins with dexamethasone sup-

pression testing to determine the source of androgen.

If androgen excess is not suppressible by dexametha-

sone, the presence of Cushings syndrome, neoplasm, or

polycystic ovary syndrome must be considered. If andro-

gen excess is dexamethasone-suppressible, a corticotro-

pin test for congenital adrenal hyperplasia is indicated. If

a neoplasm is suggested, further imaging studies (e.g.,

abdominal computed tomography for an adrenal neo-

plasm) may be warranted. Score denotes the score on

the FerrimanGallwey scale of hirsutism.

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by hani amalia on June 3, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med

353;24

www.nejm.org december

15, 2005

clinical practice

2583

testosterone levels, so assay-specific results differ

widely. The most reliable assays for measuring

free testosterone compute the level of free testos-

terone from the levels of total testosterone and sex

hormonebinding globulin.

34

Methods that purport

to assay free testosterone directly are particularly

suspect.

Routine testing for other androgens is of little

use.

6,8,9

The level of dehydroepiandrosterone sul-

fate is increased in approximately 15 percent of

women who have normal levels of total and free

testosterone. A mildly elevated level in a woman with

a normal free testosterone level is unlikely to be

clinically relevant aside from being associated with

acne.

5,35,36

Very high levels of total testosterone

(more than 200 ng per deciliter [6.94 nmol per liter])

or of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (more than

700 g per deciliter [19 mol per liter]) heighten

the likelihood of an underlying neoplasm (with el-

evated levels of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

indicating an adrenal source)

37

; however, lesser ele-

vations were present in several cases among 17

women with androgenic tumors.

24

A total testosterone level that is normal or mar-

Initial evaluation of hirsutism

Discontinue

if possible

Trial of cosmetic therapy

Prescription or non-

prescription drug use

Mild hirsutism

(score, 815)

Moderate hirsutism

(score, >15)

Risk of neoplasm:

sudden onset of

hirsutism, rapid

progression, viriliza-

tion, abdominal

or pelvic mass

Risk of polycystic ovary

syndrome: menstrual

irregularity, seborrhea,

acne, balding, obesity,

acanthosis nigricans

Risk of other endocri-

nopathy: symptoms

or signs of cortisol

excess, congenital

adrenal hyperplasia,

hyperprolactinemia,

excess growth

hormone, thyroid

dysfunction

Work up accordingly

Normal Marginally high

Early-morning plasma levels

of total and free testosterone

High

Stable or improving

course

Progressive course

or risk factors emerge

Idiopathic hirsutism Androgen excess

Recheck early-morning

levels of total and

free testosterone

Free testosterone

level normal

Free testosterone

level high

Plasma testosterone

level

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by hani amalia on June 3, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med

353;24

www.nejm.org december

15

,

2005

The

new england journal

of

medicine

2584

ginally elevated (within about 20 ng per deciliter

[0.69 nmol per liter] of the upper limits of normal)

in the absence of other features of concern proba-

bly indicates idiopathic hirsutism or idiopathic hy-

perandrogenism. Further workup is generally not

necessary unless the hirsutism progresses despite

therapy or worrisome features, such as menstrual

irregularity, obesity, or increasing masculinization,

become apparent. An assessment of the free testos-

terone level is warranted in patients with features of

other disorders, even if the total testosterone level

is not clearly elevated.

If androgen excess or features that suggest a sec-

ondary cause of hirsutism are present, referral to an

endocrinologist is reasonable. Additional workup

is discussed in the legend for Figure 4.

22,31,38

management

Hirsutism can be reduced with the use of cosmet-

ic and hormonal therapy for as long as treatment

is given. Moderate, permanent reduction of hirsut-

ism can often be achieved by physical means in op-

timal circumstances. Table 1 reviews medications

used for treatment.

Cosmetic and Physical Measures

Cosmetic measures are the cornerstone of care for

hirsutism,

39

although the costs are not covered by

insurance. Bleaching and shaving suffice for many

patients. Depilating agents and waxing treatments

are useful but tend to cause skin irritation. Eflorni-

thine hydrochloride cream (Vaniqa) was recently

approved for the treatment of facial hirsutism.

40

Data from randomized, double-blind, placebo-con-

trolled trials show that there is a maximal effect by

8 to 24 weeks, with marked improvement among

32 percent of patients (as compared with 8 percent

of patients treated with placebo).

The Food and Drug Administration has per-

mitted the marketing of many laser devices, as well

as equivalent flashlamps, for permanent hair re-

duction. There is a paucity of published clinical data

with regard to these devices.

41,42

Wavelengths of

between 694 and 1064 nm damage hair follicles

through the combination of relatively selective heat

absorption by dark hairs and penetration of the

wavelengths into the dermis. Light-skinned wom-

en are the best candidates, since they require lower

energy pulses than women with dark skin. Those

with heavily tanned or darker skin require the use

of lasers with built-in cooling devices and adjust-

ment of energy levels to minimize the risk of der-

matologic side effects. Laser treatment covers a

somewhat wider surface area, with fewer side ef-

fects and less pain, than electrolysis, temporarily

reduces by a factor of about four the need for sim-

ple cosmetic measures for several months after a

single session, and permanently reduces hair den-

sity by 30 percent or more with three to four treat-

ments at a site. Electrolysis involves the insertion of

an electrode to destroy individual follicles. Both

laser therapy and electrolysis require delivery by

trained personnel, are repetitious, expensive, and

painful, are practical only for the treatment of lim-

ited areas, and may result in local reactions, includ-

ing burns, dyspigmentation, and scarring.

Hormonal Treatments

Hormonal therapies act by either suppressing an-

drogen production or blocking the action of andro-

gens within the skin.

1

The suppression or block-

age of androgen causes hairs to revert toward the

prepubertal vellus type. The maximal effect requires

9 to 12 months of treatment because of the long

duration of the hair-growth cycle. Assessments of

efficacy are limited by their subjective nature, the

dearth of randomized, controlled trials, and the fact

that treatment of hirsutism is an off-label use of

these agents in part because androgen blockades

for this indication have been limited by liability con-

cerns related to the risk of pseudohermaphrodit-

ism in male fetuses.

EstrogenProgestin Oral Contraceptives

Oral contraceptives suppress plasma-testosterone

levels, particularly the level of free testosterone,

mainly by inhibiting ovarian function and raising

the levels of sex-hormonebinding globulin levels.

1

This method of treatment can reduce by half the

need for shaving

43

and can arrest the progression

of hirsutism from various causes, but it will not re-

verse hirsutism

2,44

; cosmetic measures should also

be used. Although any combination pill will suffice,

contraceptives with nonandrogenic progestins (Ta-

ble 1) are preferable because of their potentially fa-

vorable effects on lipid levels,

45

acne,

46

and, in the

case of drospirenone, salt retention.

47

It is unclear

whether the newer low-dose pills included in the ta-

ble carry a risk of venous thromboembolism.

48

Antiandrogens

For the substantial reduction of hirsutism, anti-

androgens are required. Competitive inhibitors of

androgen binding to the androgen receptor are su-

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by hani amalia on June 3, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med

353;24

www.nejm.org december

15, 2005

clinical practice

2585

*

T

h

e

o

r

a

l

c

o

n

t

r

a

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

s

i

n

c

l

u

d

e

d

h

e

r

e

a

r

e

e

x

a

m

p

l

e

s

o

f

p

r

e

p

a

r

a

t

i

o

n

s

w

i

t

h

l

o

w

a

n

d

r

o

g

e

n

i

c

a

c

t

i

v

i

t

y

.

T

a

b

l

e

1

.

M

e

d

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

s

C

o

m

m

o

n

l

y

U

s

e

d

f

o

r

H

i

r

s

u

t

i

s

m

.

D

r

u

g

T

y

p

e

A

c

t

i

v

e

I

n

g

r

e

d

i

e

n

t

E

x

a

m

p

l

e

M

a

j

o

r

M

e

c

h

a

n

i

s

m

I

n

d

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

C

o

n

t

r

a

i

n

d

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

s

D

o

s

e

M

a

j

o

r

S

i

d

e

E

f

f

e

c

t

s

C

e

l

l

-

c

y

c

l

e

i

n

h

i

b

i

t

o

r

E

f

l

o

r

n

i

t

h

i

n

e

h

y

d

r

o

-

c

h

l

o

r

i

d

e

,

1

3

.

9

%

V

a

n

i

q

a

I

r

r

e

v

e

r

s

i

b

l

e

i

n

h

i

b

i

t

o

r

o

f

o

r

n

i

t

h

i

n

e

d

e

-

c

a

r

b

o

x

y

l

a

s

e

F

o

c

a

l

h

i

r

s

u

t

i

s

m

P

r

e

g

n

a

n

c

y

,

b

r

e

a

s

t

-

f

e

e

d

i

n

g

T

o

p

i

c

a

l

,

t

w

i

c

e

d

a

i

l

y

R

a

s

h

,

p

o

t

e

n

t

i

a

l

s

y

s

t

e

m

i

c

t

o

x

i

c

i

t

y

w

i

t

h

w

i

d

e

s

p

r

e

a

d

a

p

p

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

O

r

a

l

c

o

n

t

r

a

-

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

s

*

E

t

h

i

n

y

l

e

s

t

r

a

d

i

o

l

3

0

g

+

d

r

o

s

p

i

r

e

n

o

n

e

3

5

g

+

n

o

r

g

e

s

t

i

m

a

t

e

5

0

g

+

e

t

h

y

n

o

d

i

o

l

d

i

a

c

e

t

a

t

e

Y

a

s

m

i

n

O

r

t

h

o

-

C

y

c

l

e

n

D

e

m

u

l

e

n

1

5

0

S

u

p

p

r

e

s

s

e

s

o

v

a

r

i

a

n

f

u

n

c

t

i

o

n

G

e

n

e

r

a

l

i

z

e

d

h

i

r

s

u

t

i

s

m

B

r

e

a

s

t

c

a

n

c

e

r

,

s

m

o

k

-

i

n

g

(

a

b

s

o

l

u

t

e

l

y

i

f

a

g

e

>

3

5

y

r

)

,

c

a

r

d

i

o

-

v

a

s

c

u

l

a

r

d

i

s

e

a

s

e

,

u

n

c

o

n

t

r

o

l

l

e

d

h

y

p

e

r

-

t

e

n

s

i

o

n

1

t

a

b

l

e

t

b

y

m

o

u

t

h

a

t

b

e

d

-

t

i

m

e

(

t

h

e

l

a

r

g

e

r

e

s

-

t

r

o

g

e

n

d

o

s

e

s

m

a

y

b

e

n

e

c

e

s

s

a

r

y

i

n

h

e

a

v

i

e

r

w

o

m

e

n

f

o

r

m

e

n

s

t

r

u

-

a

l

r

e

g

u

l

a

r

i

t

y

)

I

r

r

e

g

u

l

a

r

v

a

g

i

n

a

l

b

l

e

e

d

i

n

g

,

v

e

n

o

u

s

t

h

r

o

m

b

o

s

i

s

A

n

t

i

a

n

d

r

o

g

e

n

s

S

p

i

r

o

n

o

l

a

c

t

o

n

e

C

o

m

p

e

t

i

t

i

v

e

i

n

h

i

b

i

-

t

o

r

o

f

a

n

d

r

o

g

e

n

-

r

e

c

e

p

t

o

r

b

i

n

d

i

n

g

M

o

d

e

r

a

t

e

o

r

s

e

v

e

r

e

h

i

r

s

u

t

i

s

m

L

a

c

k

o

f

c

o

n

t

r

a

c

e

p

t

i

o

n

,

k

i

d

n

e

y

o

r

l

i

v

e

r

f

a

i

l

u

r

e

5

0

1

0

0

m

g

b

y

m

o

u

t

h

,

t

w

i

c

e

d

a

i

l

y

M

a

l

e

p

s

e

u

d

o

h

e

r

m

a

p

h

r

o

d

i

t

i

s

m

i

n

f

e

t

u

s

,

i

r

r

e

g

u

l

a

r

m

e

n

s

t

r

u

a

l

b

l

e

e

d

i

n

g

u

n

l

e

s

s

o

r

a

l

c

o

n

t

r

a

-

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

a

d

m

i

n

i

s

t

e

r

e

d

,

d

e

-

c

r

e

a

s

e

d

l

i

b

i

d

o

,

n

a

u

s

e

a

,

h

y

-

p

e

r

k

a

l

e

m

i

a

,

h

y

p

o

t

e

n

s

i

o

n

,

l

i

v

e

r

d

y

s

f

u

n

c

t

i

o

n

C

y

p

r

o

t

e

r

o

n

e

a

c

e

t

a

t

e

C

o

m

p

e

t

i

t

i

v

e

i

n

h

i

b

i

-

t

o

r

o

f

a

n

d

r

o

g

e

n

-

r

e

c

e

p

t

o

r

b

i

n

d

i

n

g

M

o

d

e

r

a

t

e

o

r

s

e

v

e

r

e

h

i

r

s

u

t

i

s

m

L

a

c

k

o

f

c

o

n

t

r

a

c

e

p

t

i

o

n

I

n

d

u

c

t

i

o

n

:

5

0

1

0

0

m

g

b

y

m

o

u

t

h

a

t

b

e

d

t

i

m

e

,

d

a

y

s

5

1

5

M

a

i

n

t

e

n

a

n

c

e

:

5

m

g

b

y

m

o

u

t

h

a

t

b

e

d

t

i

m

e

,

d

a

y

s

5

1

5

M

a

l

e

p

s

e

u

d

o

h

e

r

m

a

p

h

r

o

d

i

t

i

s

m

i

n

f

e

t

u

s

,

i

r

r

e

g

u

l

a

r

m

e

n

s

t

r

u

a

l

b

l

e

e

d

i

n

g

u

n

l

e

s

s

e

s

t

r

o

g

e

n

a

d

m

i

n

i

s

t

e

r

e

d

c

y

c

l

i

c

a

l

l

y

,

d

e

c

r

e

a

s

e

d

l

i

b

i

d

o

,

n

a

u

s

e

a

F

l

u

t

a

m

i

d

e

N

o

n

s

t

e

r

o

i

d

a

l

c

o

m

-

p

e

t

i

t

i

v

e

i

n

h

i

b

i

t

o

r

o

f

a

n

d

r

o

g

e

n

-

r

e

c

e

p

t

o

r

b

i

n

d

i

n

g

S

e

v

e

r

e

h

i

r

s

u

t

i

s

m

L

a

c

k

o

f

c

o

n

t

r

a

c

e

p

t

i

o

n

,

l

i

v

e

r

d

i

s

e

a

s

e

1

2

5

2

5

0

m

g

,

t

w

i

c

e

d

a

i

l

y

M

a

l

e

p

s

e

u

d

o

h

e

r

m

a

p

h

r

o

d

i

t

i

s

m

i

n

f

e

t

u

s

,

h

e

p

a

t

o

t

o

x

i

c

i

t

y

G

l

u

c

o

c

o

r

t

i

c

o

i

d

s

G

l

u

c

o

c

o

r

t

i

c

o

i

d

P

r

e

d

n

i

s

o

n

e

S

u

p

p

r

e

s

s

e

s

a

d

r

e

n

a

l

f

u

n

c

t

i

o

n

C

o

n

g

e

n

i

t

a

l

a

d

r

e

n

a

l

h

y

p

e

r

p

l

a

s

i

a

U

n

c

o

n

t

r

o

l

l

e

d

d

i

a

b

e

t

e

s

,

o

b

e

s

i

t

y

5

7

.

5

m

g

b

y

m

o

u

t

h

a

t

b

e

d

t

i

m

e

C

h

a

n

g

e

s

t

y

p

i

c

a

l

o

f

C

u

s

h

i

n

g

s

s

y

n

d

r

o

m

e

,

a

d

r

e

n

a

l

a

t

r

o

p

h

y

G

o

n

a

d

o

t

r

o

p

i

n

-

r

e

l

e

a

s

i

n

g

a

g

o

n

i

s

t

s

L

e

u

p

r

o

l

i

d

e

a

c

e

t

a

t

e

,

d

e

p

o

t

s

u

s

p

e

n

s

i

o

n

L

u

p

r

o

n

D

e

p

o

t

S

u

p

p

r

e

s

s

e

s

g

o

n

a

d

o

-

t

r

o

p

i

n

s

A

l

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

v

e

t

o

o

r

a

l

c

o

n

t

r

a

-

c

e

p

t

i

v

e

O

s

t

e

o

p

o

r

o

s

i

s

7

.

5

m

g

m

o

n

t

h

l

y

i

n

t

r

a

-

m

u

s

c

u

l

a

r

l

y

,

w

i

t

h

2

5

5

0

g

t

r

a

n

s

d

e

r

m

a

l

e

s

t

r

a

d

i

o

l

O

s

t

e

o

p

o

r

o

s

i

s

w

i

t

h

o

u

t

e

s

t

r

o

-

g

e

n

p

r

o

g

e

s

t

i

n

r

e

p

l

a

c

e

m

e

n

t

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by hani amalia on June 3, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med

353;24

www.nejm.org december

15

,

2005

The

new england journal

of

medicine

2586

perior to drugs that interfere with testosterone me-

tabolism.

49-52

They are effective regardless of the

cause of hyperandrogenism and may be helpful in

the treatment of idiopathic hirsutism.

2

Spirono-

lactone in a high dose (Table 1) is the antiandrogen

of choice in the United States. Cyproterone acetate

is a progestational antiandrogen available in Cana-

da, Mexico, and Europe but not in the United States.

The use of either spironolactone or cyproterone ac-

etate can be expected to reduce the FerrimanGall-

wey score by 15 to 40 percent within 6 months after

the start of therapy, although there is consider-

able variation among individual women, with the

maximum effect at 9 to 12 months. Contraceptives

containing estrogen and progestin should be used

concomitantly with these agents, since they comple-

ment antiandrogenic actions while ensuring men-

strual cyclicity and preventing pregnancy. Flutamide,

an antiandrogenic drug marketed for the treat-

ment of prostate cancer, is rarely used for hirsut-

ism because of its expense and risk of hepatocellu-

lar toxicity.

Other Hormonal Therapies

Glucocorticoid therapy (typically, 5 to 7.5 mg of

prednisone at bedtime) may improve hirsutism in

patients with nonclassic congenital adrenal hyper-

plasia. However, the effect of glucocorticoids on

hirsutism due to other causes is unclear, and slight

overdosing, as can occur even at recommended dos-

es, is associated with serious side effects.

53

The

5

a

-reductase inhibitor finasteride is less effective

for hirsutism than are antiandrogens.

52

Gonado-

tropin-releasing hormone agonists are an alterna-

tive to oral contraceptives.

44

In women with polycys-

tic ovary syndrome, insulin sensitizers (metformin

or thiazolidinediones) promote ovulation and low-

er androgen levels by about 20 percent, but there is

little evidence of a clinically significant improve-

ment in hirsutism with the use of these agents.

54,55

Data are lacking on the cost-effectiveness of vari-

ous strategies to evaluate hirsute patients and the

effect of these strategies on outcomes. The high fre-

quency of polycystic ovary syndrome among hirsute

women and the medical risks associated with this

condition support the strategy of evaluating pa-

tients for this diagnosis in many cases; however, it

is unclear which tests are routinely warranted.

Current treatment guidelines address hyperan-

drogenism rather than hirsutism per se. The 2002

guidelines of the American College of Obstetri-

cians and Gynecologists

38

favor the documenta-

tion of androgen excess in women with hirsutism

rather than the use of hirsutism as a surrogate for

androgen excess, as diagnostic criteria permit

19,20

by the measurement of total or bioavailable tes-

tosterone. The guidelines note the poor sensitivi-

ty and specificity associated with the use of cutoff

levels of androgen to rule out tumor, and they rec-

ommend measuring dehydroepiandrosterone sul-

fate levels and performing pelvic ultrasonography

only in cases of rapid virilization. The recommend-

ed role of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of poly-

cystic ovary syndrome may change in response to

the recent recommendation that the presence of

polycystic ovaries be used as an alternative diag-

nostic criterion for polycystic ovary syndrome.

20,21

Measurement of thyrotropin, prolactin, and early-

morning levels of 17

a

-hydroxyprogesterone were

recommended to rule out other androgen-excess

disorders, with evaluation for Cushings syndrome

and other rare disorders to be considered only if

suggestive symptoms or signs coexist with hirsut-

ism. The 2001 guidelines of the American Associ-

ation of Clinical Endocrinologists

31

recommend

comprehensive assessment, with the use of a spe-

cialty laboratory to measure the levels of total and

free testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sul-

fate, with further specialized testing to identify the

source of androgen excess. Both groups recom-

mend evaluating women with polycystic ovary syn-

drome for glucose intolerance and the metabolic

syndrome.

For women presenting with hirsutism, the medi-

cal history and physical examination should assess

whether there are any features to suggest the pres-

ence of a neoplasm or endocrinopathy, particularly

polycystic ovary syndrome. The patient in the vi-

gnette has mild hirsutism that is not rapidly pro-

gressive or accompanied by signs of virilization,

and her menstrual cycles are regular. Although ap-

proaches to laboratory testing vary among spe-

cialists, the patients obesity increases my concern

about the possibility of a nonclassic form of poly-

areas of uncertainty

guidelines

summary and recommendations

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by hani amalia on June 3, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med

353;24

www.nejm.org december

15, 2005

clinical practice

2587

cystic ovary syndrome, and I would evaluate a ran-

dom plasma specimen for the level of free testos-

terone (measurement of the total testosterone level

would be reasonable if reliable assessment of free

testosterone were not readily available, as shown in

Fig. 4). A trial of eflornithine chloride cream might

be tried initially for facial hirsutism, although cost

is a consideration. I would also encourage weight

control. I would plan a follow-up visit to assess

the patients response and to reassess whether ev-

idence had emerged to suggest a secondary cause

of hirsutism (if so, I would recheck early-morning

levels of free testosterone to ensure that they were

normal). If hirsutism remained inadequately con-

trolled, since there are no contraindications, I would

recommend oral contraceptives, which would be

expected to substantially reduce the need for cos-

metic treatments over a 9-to-12-month period.

I would also discuss the potential permanent ben-

efit, risks, and costs of laser hair removal or elec-

trolysis. For more severe hirsutism, spironolactone

could be added to oral-contraceptive therapy, which

would require closer monitoring for side effects

than would the other options.

Supported by grants (HD-39267, U54-041859, and RR-00055)

from the U.S. Public Health Service.

Dr. Rosenfield reports having received consulting fees from Val-

era Pharmaceuticals.

I am indebted to Drs. David A. Ehrmann and Sarah Stein for their

careful review of the manuscript and to Dr. David Whiting for advice

about Figure 3.

references

1.

Deplewski D, Rosenfield RL. Role of

hormones in pilosebaceous unit develop-

ment. Endocr Rev 2000;21:363-92.

2.

Azziz R, Carmina E, Sawaya ME. Idio-

pathic hirsutism. Endocr Rev 2000;21:347-

62.

3.

Hatch R, Rosenfield RL, Kim MH, Tred-

way D. Hirsutism: implications, etiology, and

management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1981;

140:815-30.

4.

Knochenhauer ES, Key TJ, Kahsar-Miller

M, Waggoner W, Boots LR, Azziz R. Preva-

lence of the polycystic ovary syndrome in

unselected black and white women of the

southeastern United States: a prospective

study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:

3078-82.

5.

Rosenfield RL. Hirsutism and the vari-

able response of the pilosebaceous unit to

androgen. J Invest Dermatol (in press).

6.

Reingold SB, Rosenfield RL. The rela-

tionship of mild hirsutism or acne in women

to androgens. Arch Dermatol 1987;123:209-

12.

7.

Rosenfield RL. Plasma testosterone

binding globulin and indexes of the con-

centration of unbound androgens in normal

and hirsute subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

1971;32:717-28.

8.

Wild RA, Umstot ES, Andersen RN, Ran-

ney GB, Givens JR. Androgen parameters and

their correlation with body weight in one

hundred thirty-eight women thought to have

hyperandrogenism. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1983;146:602-6.

9.

Azziz R, Sanchez LA, Knochenhauer ES,

et al. Androgen excess in women: experience

with over 1000 consecutive patients. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:453-62.

10.

Quinkler M, Sinha B, Tomlinson JW,

Bujalska IJ, Stewart PM, Arlt W. Androgen

generation in adipose tissue in women

with simple obesity a site-specific role for

17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type

5. J Endocrinol 2004;183:331-42.

11.

Rosenfield RL. Plasma free androgen

patterns in hirsute women and their diag-

nostic implications. Am J Med 1979;66:417-

21.

12.

Rosenfield RL, Moll GW Jr. The role of

proteins in the distribution of plasma andro-

gens and estradiol. In: Molinatti GM, Mar-

tini L, James VHT, eds. Androgenization in

women: pathophysiology and clinical con-

cepts. New York: Raven Press, 1983:25-45.

13.

Rosner W. The functions of corticoste-

roid-binding globulin and sex hormone bind-

ing-globulin: recent advances. Endocr Rev

1990;11:80-91.

14.

Moll GW Jr, Rosenfield RL. Testoster-

one binding and free plasma androgen con-

centrations under physiologic conditions:

characterization by flow dialysis technique.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1979;49:730-6.

15.

Nestler JE, Powers LP, Matt DW, et al.

A direct effect of hyperinsulinemia on serum

sex-hormone binding globulin levels in obese

women with the polycystic ovary syndrome.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991;72:83-9.

16.

Hogeveen KN, Cousin P, Pugeat M, Dew-

ailly D, Soudan B, Hammond GL. Human

sex hormone-binding globulin variants asso-

ciated with hyperandrogenism and ovarian

dysfunction. J Clin Invest 2002;109:973-81.

17.

Ehrmann DA, Rosenfield RL, Barnes

RB, Brigell DF, Sheikh Z. Detection of func-

tional ovarian hyperandrogenism in women

with androgen excess. N Engl J Med 1992;

327:157-62.

18.

Ehrmann DA. Polycystic ovary syndrome.

N Engl J Med 2005;352:1223-36.

19.

Zawadzki J, Dunaif A. Diagnostic crite-

ria for polycystic ovary syndrome: towards a

rational approach. In: Dunaif A, Givens J,

Haseltine F, Merriam G, eds. Polycystic ovary

syndrome. Vol. 4. Cambridge, Mass.: Black-

well Scientific, 1992:377-84.

20.

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored

PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised

2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and

long-term health risks related to polycystic

ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2004;81:19-25.

21.

Azziz R. Diagnostic criteria for poly-

cystic ovary syndrome: a reappraisal. Fertil

Steril 2005;83:1343-6.

22.

Buggs C, Rosenfield RL. Polycystic ovary

syndrome in adolescence. Endocrinol Metab

Clin North Am 2005;34:677-705.

23.

Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The

metabolic syndrome. Lancet 2005;365:1415-

28.

24.

Kaltsas GA, Isidori AM, Kola BP, et al.

The value of the low-dose dexamethasone

suppression test in the differential diagno-

sis of hyperandrogenism in women. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:2634-43.

25.

Rosenfield RL, Cohen RM, Talerman A.

Lipid cell tumor of the ovary in reference to

adult-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia

and polycystic ovary syndrome: a case re-

port. J Reprod Med 1987;32:363-9.

26. Souter I, Sanchez LA, Perez M, Bar-

tolucci AA, Azziz R. The prevalence of andro-

gen excess among patients with minimal

unwanted hair growth. Am J Obstet Gynecol

2004;191:1914-20.

27. Nelson-DeGrave VL, Wickenheisser JK,

Cockrell JE, et al. Valproate potentiates andro-

gen biosynthesis in human ovarian theca

cells. Endocrinology 2004;145:799-808.

28. Polson DW, Adams J, Wadsworth J, Franks

S. Polycystic ovaries a common finding in

normal women. Lancet 1988;1:870-2.

29. Glintborg D, Hermann AP, Brusgaard

K, Hangaard J, Hagen C, Andersen M. Signif-

icantly higher adrenocorticotropin-stimu-

lated cortisol and 17-hydroxyprogesterone

levels in 337 consecutive, premenopausal,

caucasian, hirsute patients compared with

healthy controls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

2005;90:1347-53.

30. Wajchenberg BL, Albergaria Pereira MA,

Medonca BB, et al. Adrenocortical carcino-

ma: clinical and laboratory observations.

Cancer 2000;88:711-36.

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by hani amalia on June 3, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 353;24 www.nejm.org december 15, 2005 2588

clinical practice

31. Goodman NF, Bledsoe MB, Futterweit

W, et al. American Association of Clinical

Endocrinologists medical guidelines for

clinical practice for the diagnosis and treat-

ment of hyperandrogenic disorders. Endocr

Pract 2001;7:120-34.

32. Taieb J, Mathian B, Millot F, et al. Testos-

terone measured by 10 immunoassays and by

isotope-dilution gas chromatography-mass

spectrometry in sera from 116 men, women,

and children. Clin Chem 2003;49:1381-95.

33. Legro RS, Driscoll D, Strauss JF III, Fox

J, Dunaif A. Evidence for a genetic basis for

hyperandrogenemia in polycystic ovary syn-

drome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:

14956-60.

34. Miller KK, Rosner W, Lee H, et al. Mea-

surement of free testosterone in normal

women and women with androgen defi-

ciency: comparison of methods. J Clin Endo-

crinol Metab 2004;89:525-33.

35. Marynick SP, Chakmakjian ZH, McCaf-

free DL, Herndon JH Jr. Androgen excess in

cystic acne. N Engl J Med 1983;308:981-6.

36. Azziz R, Dewailly D, Owerbach D. Non-

classic adrenal hyperplasia: current concepts.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994;78:810-5.

37. ACOG technical bulletin: evaluation and

treatment of hirsute women. Number 203

March 1995 (replaces no. 103, April 1987).

Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1995;49:341-6.

38. American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin: clini-

cal management guidelines for obstetrician-

gynecologists: number 41, December 2002.

Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:1389-402.

39. Azziz R. The evaluation and manage-

ment of hirsutism. Obstet Gynecol 2003;

101:995-1007.

40. Balfour JA, McClellan K. Topical eflorni-

thine. Am J Clin Dermatol 2001;2:197-201.

41. Dierickx CC. Hair removal by lasers and

intense pulsed light sources. Dermatol Clin

2002;20:135-46.

42. Battle EF Jr, Hobbs LM. Laser-assisted

hair removal for darker skin types. Dermatol

Ther 2004;17:177-83.

43. Hancock KW, Levell MJ. The use of

oestrogen-progestogen preparations in the

treatment of hirsutism in the female. J Obstet

Gynaecol Br Commonw 1974;81:804-11.

44. Heiner JS, Greendale GA, Kawakami AK,

et al. Comparison of a gonadotropin-releas-

ing hormone agonist and a low dose oral

contraceptive given alone or together in the

treatment of hirsutism. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab 1995;80:3412-8.

45. Kuhl H. Comparative pharmacology of

newer progestogens. Drugs 1996;51:188-

215.

46. van Vloten WA, Sigurdsson V. Selecting

an oral contraceptive agent for the treatment

of acne in women. Am J Clin Dermatol 2004;

5:435-41.

47. Krattenmacher R. Drospirenone: phar-

macology and pharmacokinetics of a unique

progestogen. Contraception 2000;62:29-38.

48. Petitti DB. Combination estrogenproges-

tin oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med 2003;

349:1443-50. [Erratum, N Engl J Med 2004;

350:92.]

49. Venturoli S, Marescalchi O, Colombo

FM, et al. A prospective randomized trial

comparing low dose flutamide, finaster-

ide, ketoconazole, and cyproterone ace-

tate-estrogen regimens in the treatment of

hirsutism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;

84:1304-10.

50. Moghetti P, Tosi F, Tosti A, et al. Com-

parison of spironolactone, flutamide, and

finasteride efficacy in the treatment of hir-

sutism: a randomized, double blind, placebo-

controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

2000;85:89-94.

51. Van der Spuy ZM, le Roux PA. Cyprot-

erone acetate for hirsutism. Cochrane Data-

base Syst Rev 2003;4:CD001125.

52. Farquhar C, Lee O, Toomath R, Jepson

R. Spironolactone versus placebo or in com-

bination with steroids for hirsutism and/or

acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;4:

CD000194.

53. Rittmaster RS, Givner ML. Effect of dai-

ly and alternate day low dose prednisone on

serum cortisol and adrenal androgens in

hirsute women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

1988;67:400-3.

54. Harborne L, Fleming R, Lyall H, Norman

J, Sattar N. Descriptive review of the evidence

for the use of metformin in polycystic ovary

syndrome. Lancet 2003;361:1894-901.

55. Lord JM, Flight IH, Norman RJ. Insulin-

sensitising drugs (metformin, troglitazone,

rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, D-chiro-inosi-

tol) for polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2003;3:CD003053.

Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society.

apply for jobs electronically at the nejm careercenter

Physicians registered at the NEJM CareerCenter can apply for jobs electronically using

their own cover letters and CVs. You can keep track of your job-application history with

a personal account that is created when you register with the CareerCenter and apply

for jobs seen online at our Web site. Visit www.nejmjobs.org for more information.

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org by hani amalia on June 3, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Evaluacion HirsutismoDocument8 paginiEvaluacion HirsutismoAli ChongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sign of Hyperandrogenism PDFDocument6 paginiSign of Hyperandrogenism PDFmisbah_mdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Secamenhyper 120208102817 Phpapp02Document31 paginiSecamenhyper 120208102817 Phpapp02Mohan DassÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2004 Bembo 511 7Document7 paginiCleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2004 Bembo 511 7DewinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sind Ovario Poliquistico 2016 - NejmDocument11 paginiSind Ovario Poliquistico 2016 - NejmAntonio MoncadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 9: GynecologyDe la EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 9: GynecologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gynecomastia: Submitted byDocument7 paginiGynecomastia: Submitted byKailash KhatriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hair AnDocument6 paginiHair AnInnestyas ChrisantyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lourence M. Patagoc Block 1 SGD Group 1 Module 2 GYNE Case Hirsutism and VirilizationDocument48 paginiLourence M. Patagoc Block 1 SGD Group 1 Module 2 GYNE Case Hirsutism and VirilizationFernando AnibanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 06 - 213the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome-A Systematic ReviewDocument4 pagini06 - 213the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome-A Systematic ReviewAnni SholihahÎncă nu există evaluări

- HirsutismDocument19 paginiHirsutismCita KresnandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- V Polycystic Ovarysyndrome: EpidemiologyDocument13 paginiV Polycystic Ovarysyndrome: Epidemiologyrolla_hiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome 2016 NEJMDocument11 paginiPolycystic Ovary Syndrome 2016 NEJMGabrielaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pcos - Clinical Case DiscussionDocument4 paginiPcos - Clinical Case Discussionreham macadatoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation and Treatment of Women With HirsutismDocument8 paginiEvaluation and Treatment of Women With HirsutismDewi Puji AstutikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Precocious Puberty With Primary Hypothyroidism Due To Autoimmune ThyroiditisDocument3 paginiPrecocious Puberty With Primary Hypothyroidism Due To Autoimmune ThyroiditisShohel RanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hyperandrogenism: Arrest Occurs When The Granulosa Cells of The Ovaries Normally Begin To ProduceDocument7 paginiHyperandrogenism: Arrest Occurs When The Granulosa Cells of The Ovaries Normally Begin To ProduceNathan JeffreyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prolactinoma MEdscapeDocument12 paginiProlactinoma MEdscapeHenryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manejo MenopausiaDocument8 paginiManejo MenopausialuisafernandasalamanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recurrent Preg LossDocument1 paginăRecurrent Preg Lossratna_habibahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Androgen Insensitivity SyndromeDocument10 paginiAndrogen Insensitivity SyndromelemaloukÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirsutism and HomoeopathyDocument9 paginiHirsutism and HomoeopathyDr. Rajneesh Kumar Sharma MD HomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Menarche and AdolescentDocument10 paginiMenarche and AdolescentDrDiya AlkayidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crie2014 987272 PDFDocument4 paginiCrie2014 987272 PDFwatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- MRCPCH Guide EndoDocument7 paginiMRCPCH Guide EndoRajiv KabadÎncă nu există evaluări

- p373 PDFDocument8 paginip373 PDFwatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amenorrhea and SpaniomenorrheasDocument59 paginiAmenorrhea and SpaniomenorrheasIdiAmadouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adolescent Gynecologic Care QUESTIONS 1, 2, 3Document7 paginiAdolescent Gynecologic Care QUESTIONS 1, 2, 3patelkn_2005Încă nu există evaluări

- Amenorrhea SGDDocument44 paginiAmenorrhea SGDMichelle Lariosa ChangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Peds Review: Blood/Neoplastic Disorders: Factor VIII Clotting Prolonged Partial Thromboplastin TimeDocument4 paginiPeds Review: Blood/Neoplastic Disorders: Factor VIII Clotting Prolonged Partial Thromboplastin TimeDiana HyltonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hyperemesis Gravidarum: By: Solomon Berhe OBGYN ResidentDocument73 paginiHyperemesis Gravidarum: By: Solomon Berhe OBGYN Residentmuleget haileÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hypoglycemia in Diabetes: Pathophysiology, Prevalence, and PreventionDe la EverandHypoglycemia in Diabetes: Pathophysiology, Prevalence, and PreventionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Obstetrics and Gynecology Sixth Edition Obstetrics and Gynecology Beckman Chapter 36Document8 paginiObstetrics and Gynecology Sixth Edition Obstetrics and Gynecology Beckman Chapter 363hondoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hirsutism: Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument6 paginiHirsutism: Diagnosis and TreatmentAnonymous ysrxggk21cÎncă nu există evaluări

- Healy1994 PDFDocument6 paginiHealy1994 PDFAdiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prep For USMLEDocument96 paginiPrep For USMLEdrhassam90Încă nu există evaluări

- Polycystic OvaryDocument25 paginiPolycystic OvaryAli AbdElnaby SalimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gynecomastia: Clinical PracticeDocument9 paginiGynecomastia: Clinical PracticeDewinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocument11 paginiPolycystic Ovary SyndromeViridiana Briseño GarcíaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment of Androgens in Women With Adult-Onset AcneDocument4 paginiAssessment of Androgens in Women With Adult-Onset AcneFadhila NurrahmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Upd. MEANING OF INFERTILITYDocument9 paginiUpd. MEANING OF INFERTILITYCharles DebrahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Adults - UpToDateDocument27 paginiDiagnosis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Adults - UpToDatepeishanwang90Încă nu există evaluări

- Crypt Orchid IsmDocument6 paginiCrypt Orchid IsmJayson Almario AranasÎncă nu există evaluări

- NP020110 P18table1Document1 paginăNP020110 P18table1Celine SuryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AmennorheaDocument14 paginiAmennorheakutra3000Încă nu există evaluări

- 1999 GH in Adults and ChildrenDocument11 pagini1999 GH in Adults and ChildrenGavril Diana AlexandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment of Thyroid and Prolactin Levels Among The Women With Abnormal Uterine BleedingDocument6 paginiAssessment of Thyroid and Prolactin Levels Among The Women With Abnormal Uterine BleedingMezouar AbdennacerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gynecomastia in Adolescent MalesDocument7 paginiGynecomastia in Adolescent MalesIbrahim AbdiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Name Class Section Subject: Sohon Sen XI B BiologyDocument36 paginiName Class Section Subject: Sohon Sen XI B BiologySohon SenÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3current Evaluation of Amenorrhea - A Committee OpinionDocument9 pagini3current Evaluation of Amenorrhea - A Committee Opinionjorge nnÎncă nu există evaluări

- PCOSDocument15 paginiPCOSAndyan Adlu PrasetyajiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assesment of Amen or RheaDocument49 paginiAssesment of Amen or Rheakhadzx100% (2)

- Infertility: SymptomsDocument9 paginiInfertility: SymptomsVyshak KrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- First Page PDFDocument1 paginăFirst Page PDFAmenÎncă nu există evaluări

- HP Oct08 AndrogenismDocument8 paginiHP Oct08 AndrogenismgratianusbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Under Supervision ofDocument7 paginiPolycystic Ovary Syndrome: Under Supervision ofHend HamedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Menstrual Disorders in Adolescents: The Internet Journal of Gynecology and ObstetricsDocument34 paginiMenstrual Disorders in Adolescents: The Internet Journal of Gynecology and ObstetricsNayla Adira04Încă nu există evaluări

- DR - Sahni's Homoeopathy Clinic & Research Center Pvt. LTD: July 2004Document0 paginiDR - Sahni's Homoeopathy Clinic & Research Center Pvt. LTD: July 2004Ramot Tribaya Recardo PardedeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fast Facts: Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome: Raising awareness of a rare genetic diseaseDe la EverandFast Facts: Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome: Raising awareness of a rare genetic diseaseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale (WBIS) : For Adolescents and AdultsDocument2 paginiWechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale (WBIS) : For Adolescents and AdultsAnonymous kltUTaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fill in The Blanks With Don't Have To, Mustn'tDocument2 paginiFill in The Blanks With Don't Have To, Mustn'tAnonymous kltUTaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PIHDocument30 paginiPIHPatcharavit PloynumponÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preeclampsia/Eclampsia: An Insight Into The Dilemma of Treatment by The AnesthesiologistDocument10 paginiPreeclampsia/Eclampsia: An Insight Into The Dilemma of Treatment by The AnesthesiologistAnonymous kltUTaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AlopeciaDocument11 paginiAlopeciaAnonymous kltUTa100% (1)

- Sexual Self Thales ReportDocument22 paginiSexual Self Thales ReportToni GonzalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Miracle Results of Fasting - Dave WilliamsDocument129 paginiThe Miracle Results of Fasting - Dave WilliamsGikonyo Stellar94% (17)

- ECPs and IUD NotesDocument8 paginiECPs and IUD NotesYu, Denise Kyla BernadetteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Family Planning Allows People To Attain Their Desired Number of Children and Determine The Spacing of PregnanciesDocument6 paginiFamily Planning Allows People To Attain Their Desired Number of Children and Determine The Spacing of PregnanciesMareeze HattaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diane Pills Drug StudyDocument4 paginiDiane Pills Drug StudyDawn EncarnacionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Improving Your Health With Vitamin C - Adams, Ruth, 1911 - Murray, FrankDocument164 paginiImproving Your Health With Vitamin C - Adams, Ruth, 1911 - Murray, FrankAnonymous gwFqQcnaX100% (1)

- Reproductive Health PowerNotes by KT SirDocument2 paginiReproductive Health PowerNotes by KT Sirjumihuss08Încă nu există evaluări

- Sander 2009Document6 paginiSander 2009Rika Yulizah GobelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ceu Guidance Problematic Bleeding Hormonal ContraceptionDocument28 paginiCeu Guidance Problematic Bleeding Hormonal Contraceptionmarina_shawkyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contraception ChartDocument4 paginiContraception ChartTJÎncă nu există evaluări

- Postpartum Car1Document11 paginiPostpartum Car1Claire Alvarez OngchuaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Estrogen Type On Cardiovascular Safety of Combined OralDocument12 paginiImpact of Estrogen Type On Cardiovascular Safety of Combined OralMary SuescaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bp503t Pcol Unit-VDocument46 paginiBp503t Pcol Unit-VAakkkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thunder God Vine Uses, Benefits & Dosage - Drugs - Com Herbal DatabaseDocument5 paginiThunder God Vine Uses, Benefits & Dosage - Drugs - Com Herbal DatabaseÁtilaÎncă nu există evaluări