Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Încărcat de

herbert23Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Încărcat de

herbert23Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Ludwig Wittgenstein: Analysis of Language

The direction of analytic philosophy in the twentieth century was altered not once but

twice by the enigmatic Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. By his own

philosophical work and through his influence on several generations of other thinkers,

Wittgenstein transformed the nature of philosophical activity in the English-speaking

world. rom two distinct approaches, he sought to show that traditional philosophical

problems can be avoided entirely by application of an appropriate methodology, one that

focuses on analysis of language.

The !early! Wittgenstein worked closely with Russell and shared his conviction that

the use of mathematical logic held great promise for an understanding of the world. "n the

tightly-structured declarationss of the Logische-Philosophische Abhandlung #Tractatus

Logico-Philosophicus$ #%&''$, Wittgenstein tried to spell out precisely what a logically

constructed language can #and cannot$ be used to say. "ts seven basic propositions simply

state that language, thought, and reality share a common structure, fully e(pressible in

logical terms.

)n Wittgenstein*s view, the world consists entirely of facts. #Tractatus %.%$ +uman

beings are aware of the facts by virtue of our mental representations or thoughts, which

are most fruitfully understood as picturing the way things are. #Tractatus '.%$ These

thoughts are, in turn, e(pressed in propostitions, whose form indicates the position of

these facts within the nature of reality as a whole and whose content presents the truth-

conditions under which they correspond to that reality. #Tractatus ,$ Everything that is

true-that is, all the facts that constitute the world-can in principle be e(pressed by

atomic sentences. "magine a comprehensive list of all the true sentences. They would

picture all of the facts there are, and this would be an ade.uate representation of the

world as a whole.

The tautological e(pressions of logic occupy a special role in this language-scheme.

Because they are true under all conditions whatsoever, tautologies are literally nonsense/

Wittgenstein

0ife and Works

. . 1icture Theory

. . act and 2alue

. . 3ew 4ethods

. . 0anguage 5ames

. . 1rivate 0anguage

Bibliography

"nternet 6ources

they convey no information about what the facts truly are. But since they are true under

all conditions whatsoever, tautologies reveal the underlying structure of all language,

thought, and reality. #Tractatus 7.%$ Thus, on Wittgenstein*s view, the most significant

logical features of the world are not themselves additional facts about it.

What Cannot be Said

This is the ma8or theme of the Tractatus as a whole/ since propositions merely e(press

facts about the world, propositions in themselves are entirely devoid of value. The facts

are 8ust the facts. Everything else, everything about which we care, everything that might

render the world meaningful, must reside elsewhere. #Tractatus 7.,$ A properly logical

language, Wittgenstein held, deals only with what is true. Aesthetic 8udgments about

what is beautiful and ethical 8udgments about what is good cannot even be e(pressed

within the logical language, since they transcend what can be pictured in thought. They

aren*t facts. The achievement of a wholly satisfactory description of the way things are

would leave unanswered #but also unaskable$ all of the most significant .uestions with

which traditional philosophy was concerned. #Tractatus 7.9$

Thus, even the philosophical achievements of the Tractatus itself are nothing more

than useful nonsense: once appreciated, they are themselves to be discarded. The book

concludes with the lone statement/

"Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent."

#Tractatus ;$ This is a stark message indeed, for it renders literally unspeakable so much

of human life. As Wittgenstein*s friend and colleague rank <amsey put it,

"What we can't say we can't say, and we can't whistle it either."

"t was this carefully-delineated sense of what a logical language can properly e(press that

influenced members of the 2ienna =ircle in their formulation of the principles of logical

positivism. Wittgenstein himself supposed that there was nothing left for philosophers to

do. True to this conviction, he abandoned the discipline for nearly a decade.

New Directions

By the time Wittgenstein returned to =ambridge in %&'>, however, he had begun to

.uestion the truth of his earlier pronouncements. The problem with logical analysis is that

it demands too much precision, both in the definition of words and in the representation

of logical structure. "n ordinary language, applications of a word often bear only a

!family resemblance! to each other, and a variety of grammatical forms may be used to

e(press the same basic thought. But under these conditions, Wittgenstein now reali?ed,

the hope of developing an ideal formal language that accurately pictures the world is not

only impossibly difficult but also wrong-headed.

@uring this fertile period, Wittgenstein published nothing, but worked through his new

notions in classroom lectures. 6tudents who witnessed these presentations tried to convey

both the style and the content in their shared notes, which were later published as The

Blue and Brown Books #%&9>$. G.E. oore also sat in on Wittgenstein*s lectures during

the early thirties and later published a summary of his own copious notes. What appears

in these partial records is the emergence of a new conception of philosophy.

The picture theory of meaning and logical atomism are untenable, Wittgenstein now

maintained, and there is no reason to hope that any better versions of these basic positions

will ever come along. =laims to have achieved a correct, final analysis of language are

invariably mistaken. 6ince philosophical problems arise from the intellectual

bewilderment induced by the misuse of language, the only way to resolve them is to use

e(amples from ordinary language to deflate the pretensions of traditional thought. The

only legitimate role for philosophy, then, is as a kind of therapy-a remedy for the

bewitchment of human thought by philosophical language. =areful attention to the actual

usage of ordinary language should help avoid the conceptual confusions that give rise to

traditional difficulties.

Language as Game

)n this conception of the philosophical enterprise, the vagueness of ordinary usage is

not a problem to be eliminated but rather the source of linguistic riches. "t is misleading

even to attempt to fi( the meaning of particular e(pressions by linking them referentially

to things in the world. The meaning of a word or phrase or proposition is nothing other

than the set of #informal$ rules governing the use of the e(pression in actual life.

0ike the rules of a game, Wittgenstein argued, these rules for the use of ordinary

language are neither right nor wrong, neither true nor false/ they are merely useful for the

particular applications in which we apply them. The members of any community-cost

accountants, college students, or rap musicians, for e(ample-develop ways of speaking

that serve their needs as a group, and these constitute the language-game #4oore*s notes

refer to the !system! of language$ they employ. +uman beings at large constitute a

greater community within which similar, though more widely-shared, language-games

get played. Although there is little to be said in general about language as a whole,

therefore, it may often be fruitful to consider in detail the ways in which particular

portions of the language are used.

Even the fundamental truths of arithmetic, Wittgenstein now supposed, are nothing

more than relatively stable ways of playing a particular language-game. This account

re8ects both logicist and intuitionist views of mathematics in favor of a normative

conception of its use. ! " # $ % is nothing other than a way we have collectively decided

to speak and write, a handy, shared language-game. The point once more is merely to

clarify the way we use ordinary language about numbers.

Pain and Priate Language

)ne application of the new analytic techni.ue that Wittgenstein himself worked out

appears in several connected sections of the posthumously-published Philosophical

Investigations #%&9A$. "n discussions of the concept of !understanding,! traditional

philosophers tended to suppose that the operation of the human mind involves the

continuous operation of an inner or mental process of pure thinking. But Wittgenstein

pointed out that if we did indeed have private inner e(periences, it would be possible to

represent them in a corresponding language. )n detailed e(amination, however, he

concluded that the very notion of such a private language is utterly nonsensical.

"f any of my e(periences were entirely private, then the pain that " feel would surely

be among them. Bet other people commonly are said to know when " am in pain. "ndeed,

Wittgenstein pointed out that " would never have learned the meaning of the word !pain!

without the aid of other people, none of whom have access to the supposed private

sensations of pain that " feel. or the word !pain! to have any meaning at all presupposes

some sort of e(ternal verification, a set of criteria for its correct application, and they

must be accessible to others as well as to myself. Thus, the traditional way of speaking

about pain needs to be abandoned altogether.

3otice that e(actly the same kind of argument will work with respect to every other

attempt to speak about our supposedly inner e(periences. There is no systematic way to

coordinate the use of words that e(press sensations of any kind with the actual sensations

that are supposed to occur within myself and other agents. Wittgenstein proposed that we

imagine that each human being carries a tiny bo( whose contents is observed only by its

owner/ even if we all agree to use the word !beetle! to refer to what is in the bo(, there is

no way to establish a non-linguistic similarity between the contents of my own bo( and

that of anyone else*s. Cust so, the use of language for pains or other sensations can only be

associated successfully with dispositions to behave in certain ways. 1ain is whatever

makes someone #including me$ writhe and groan.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- How To Effectively CommunicateDocument46 paginiHow To Effectively CommunicateDiana MÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tractatus Logico PhilosophicusDocument120 paginiTractatus Logico PhilosophicusPhong LeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review of Wittgenstein's Language GameDocument6 paginiReview of Wittgenstein's Language GamechicanalizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Pope Like None Had Ever SeenDocument4 paginiA Pope Like None Had Ever Seenherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: the original authoritative editionDe la EverandTractatus Logico-Philosophicus: the original authoritative editionEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (446)

- SPIRITUAL AND MORAL DEVELOPMENT LatestDocument16 paginiSPIRITUAL AND MORAL DEVELOPMENT LatestPatrick Tew100% (2)

- Ludwig Wittgenstein LANGUAGE GAMESDocument10 paginiLudwig Wittgenstein LANGUAGE GAMESFiorenzo TassottiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ludwig Wittgenstein NotesDocument3 paginiLudwig Wittgenstein Noteskavita_12Încă nu există evaluări

- Establishing Scientific Classroom Discourse Communities - Multiple Voices of TeachingDocument343 paginiEstablishing Scientific Classroom Discourse Communities - Multiple Voices of TeachingPhalangchok Wanphet100% (1)

- Aims, Goals and ObjectiveDocument6 paginiAims, Goals and ObjectiveRoshan PM100% (1)

- Salvador Dali The Rotten DonkeyDocument4 paginiSalvador Dali The Rotten DonkeyvladaalisterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kenneth W. Spence - Behavior Theory and Conditioning-Yale University Press (1956) PDFDocument267 paginiKenneth W. Spence - Behavior Theory and Conditioning-Yale University Press (1956) PDFVíctor FuentesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Ludwig Wittgenstein: OverviewDe la EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Ludwig Wittgenstein: OverviewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team TeachingDocument31 paginiTeam Teachingadhawan_15100% (1)

- McGuinn-Wittgenstein and Internal RelationDocument15 paginiMcGuinn-Wittgenstein and Internal Relationfireye66Încă nu există evaluări

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Ethics and the Mystical in WittgensteinDe la EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Ethics and the Mystical in WittgensteinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Natural PhilosophyDocument8 paginiNatural PhilosophyNadyuskaMosqueraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Totalitarianism of Therapeutic PhilosophyDocument18 paginiThe Totalitarianism of Therapeutic PhilosophyNadia Leyla AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ten Main Issues in Wittgenstein - A TeacDocument8 paginiTen Main Issues in Wittgenstein - A Teacyy1231231Încă nu există evaluări

- Later WittgensteinDocument8 paginiLater WittgensteinJyoti RanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 3 Ordinary Language Philosophy: 3.0 ObjectivesDocument11 paginiUnit 3 Ordinary Language Philosophy: 3.0 ObjectivesyaminiÎncă nu există evaluări

- WittgensteinDocument5 paginiWittgensteinBently JohnsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wittgenstein Grammar and Its Arbitrarine PDFDocument22 paginiWittgenstein Grammar and Its Arbitrarine PDFAngelika Rae RamiterreÎncă nu există evaluări

- On WittgensteinDocument10 paginiOn Wittgensteinshawn100% (1)

- 102-Article Text-388-1-10-20210604Document16 pagini102-Article Text-388-1-10-20210604laurapachecodelahozÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wittgenstein Limitation of LanguageDocument6 paginiWittgenstein Limitation of LanguageJonie RoblesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ijrar Issue 1628Document3 paginiIjrar Issue 1628Gesna SonkarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Primacy of Use Over Naming (For RAVENSHAW CONFORENCE)Document9 paginiThe Primacy of Use Over Naming (For RAVENSHAW CONFORENCE)Alok Kumar SahuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Christian Paul Oligario Cervantes-Gabo Venturillo Y JavarezDocument3 paginiChristian Paul Oligario Cervantes-Gabo Venturillo Y JavarezKentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language Game Dan Postmodern ConditonDocument11 paginiLanguage Game Dan Postmodern ConditonEko PrasetyoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Debunking Ludwig WittgensteinDocument3 paginiDebunking Ludwig WittgensteinMark Lonne PeliñoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 30 PDFDocument11 paginiChapter 30 PDFDamla Nihan YildizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ludwig Wittgenstein and His Philosophies On LanguageDocument4 paginiLudwig Wittgenstein and His Philosophies On LanguageApple IgharasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wittgenstein and Heidegger The RelationsDocument11 paginiWittgenstein and Heidegger The Relationsanethanhngoctam88Încă nu există evaluări

- Daoism and WittgensteinDocument9 paginiDaoism and WittgensteinPhilip HanÎncă nu există evaluări

- I Dedicate This Treatise To My Father Who Was An AcademicDocument40 paginiI Dedicate This Treatise To My Father Who Was An AcademicAlexanderGordonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wittgestein and AustinDocument7 paginiWittgestein and Austinsonce3Încă nu există evaluări

- WittgensteinDocument4 paginiWittgensteinKalyaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Insights From Wit PhilosophyDocument9 paginiInsights From Wit PhilosophychicanalizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Philosophical Joke Book?: I. What's So Funny About Wittgenstein?Document10 paginiA Philosophical Joke Book?: I. What's So Funny About Wittgenstein?Ana-Marija MalovecÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (The original 1922 edition with an introduction by Bertram Russell)De la EverandTractatus Logico-Philosophicus (The original 1922 edition with an introduction by Bertram Russell)Încă nu există evaluări

- Schneider 1990 Philosophical InvestigationsDocument17 paginiSchneider 1990 Philosophical InvestigationsjamesmacmillanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wittgenstein On Meaning and UnderstandingDocument15 paginiWittgenstein On Meaning and UnderstandingtoolpeterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tractatus Logico Philosophicus General SummaryDocument15 paginiTractatus Logico Philosophicus General SummaryEvielyn MateoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Remarks On Ludwig Wittgenstein and Behaviourism: Susan ByrneDocument9 paginiRemarks On Ludwig Wittgenstein and Behaviourism: Susan ByrneLazar MilinÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3concept of Language - Roshan Ara PDFDocument16 pagini3concept of Language - Roshan Ara PDFDamla Nihan YildizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wittgenstein On The Experience of Meaning - Historical and Contemporary PerspectivesDocument8 paginiWittgenstein On The Experience of Meaning - Historical and Contemporary PerspectivescarouselÎncă nu există evaluări

- Idealisation: A Gordon 2009Document17 paginiIdealisation: A Gordon 2009agord021Încă nu există evaluări

- Summary of The Lecture On The Works of Later WittgensteinDocument2 paginiSummary of The Lecture On The Works of Later WittgensteinThePhilosophicalGamerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wittgenstein and The Open Concept of Art Joe Dobzynski Jr.Document4 paginiWittgenstein and The Open Concept of Art Joe Dobzynski Jr.rustycarmelina108Încă nu există evaluări

- What Is PhilosophyDocument9 paginiWhat Is PhilosophyUzumakiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Meaning-Sharing NetworkDocument14 paginiThe Meaning-Sharing NetworkJohn HaglundÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pictures and Gestures: Body. It Is This Particular Analogy, However, On Which He Places Great ImportDocument15 paginiPictures and Gestures: Body. It Is This Particular Analogy, However, On Which He Places Great ImportT.Încă nu există evaluări

- Bojin - Machines and MeaningDocument12 paginiBojin - Machines and MeaningBogdan SzczurekÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Corpses of Times Generations: Volume TwoDe la EverandThe Corpses of Times Generations: Volume TwoÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Philosophical AnalysisDocument3 paginiOn Philosophical AnalysisBaby Lyn Ann TanalgoÎncă nu există evaluări

- H B L: S T W: Uman Ehavior As Anguage OME Houghts On IttgensteinDocument13 paginiH B L: S T W: Uman Ehavior As Anguage OME Houghts On IttgensteinhalconhgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wittgenstein ThoughtDocument3 paginiWittgenstein ThoughtB.e.i.x MÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wittgenstein, Ordinary Language, and PoeticityDocument22 paginiWittgenstein, Ordinary Language, and PoeticityButch CabayloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jade McMahon - WittgensteinLDocument5 paginiJade McMahon - WittgensteinLJadeemcÎncă nu există evaluări

- UNIT I - IntroductionDocument23 paginiUNIT I - IntroductiondecarvalhothiÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Aesthetics of The Ordinary: Wittgenstein and John Cage: James M. FieldingDocument11 paginiAn Aesthetics of The Ordinary: Wittgenstein and John Cage: James M. FieldingH mousaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Borderlands/La Frontera by María LugonesDocument26 paginiOn Borderlands/La Frontera by María LugonesBen GalinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wittgenstein's EssentialismDocument16 paginiWittgenstein's EssentialismMaristela RochaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: Logisch-Philosophische AbhandlungDocument122 paginiTractatus Logico-Philosophicus: Logisch-Philosophische AbhandlungSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wittgenstein On Metaphor: Universidade Federal Fluminense - Department of PhilosophyDocument18 paginiWittgenstein On Metaphor: Universidade Federal Fluminense - Department of PhilosophyjmfontanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- M-Journal of The History of Ideas Vol. 27, No. 1Document9 paginiM-Journal of The History of Ideas Vol. 27, No. 1epifanikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is The Mass A MealDocument5 paginiIs The Mass A Mealherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- Eucharist-Understanding Christ's BodyDocument5 paginiEucharist-Understanding Christ's Bodyherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- Have Sacraments ChangedDocument5 paginiHave Sacraments Changedherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- Eucharist-Food For MissionDocument3 paginiEucharist-Food For Missionherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- Eucharist-Sign and Source of UnityDocument5 paginiEucharist-Sign and Source of Unityherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- Con Validation SDocument2 paginiCon Validation Sherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- Encourage Individual ConfessionDocument1 paginăEncourage Individual Confessionherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- 26 Commitments For A Man 1229022239603084 1Document2 pagini26 Commitments For A Man 1229022239603084 1herbert23Încă nu există evaluări

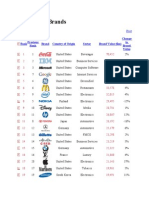

- Best Global BrandsDocument5 paginiBest Global Brandsherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- Biblical Roots of ConfirmationDocument4 paginiBiblical Roots of Confirmationherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- Creation Movie ReviewDocument4 paginiCreation Movie Reviewherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- (Silence) - Eucharistic SilenceDocument4 pagini(Silence) - Eucharistic Silenceherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- Back To The Basics: Navigating The Catechism: Gary ShirleyDocument6 paginiBack To The Basics: Navigating The Catechism: Gary Shirleyherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- Making Up For Bad Health HabitsDocument4 paginiMaking Up For Bad Health Habitsherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- Change ManagementDocument2 paginiChange Managementherbert23Încă nu există evaluări

- Multimedia Learning in Second Language AquisitionDocument24 paginiMultimedia Learning in Second Language AquisitionJuan Serna100% (2)

- From Ruth Campbell and Helen Berry: Action Research Toolkit, Edinburgh Youth Inclusion Partnership, 2001Document14 paginiFrom Ruth Campbell and Helen Berry: Action Research Toolkit, Edinburgh Youth Inclusion Partnership, 2001akankshapotdarÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Priori Bealer (1999) PDFDocument27 paginiA Priori Bealer (1999) PDFDiego MontoyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural CompetenceDocument2 paginiCultural Competencered_rose50100% (1)

- Lecture 1Document16 paginiLecture 1tranmoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan Length MetresDocument2 paginiLesson Plan Length Metresapi-3638209580% (1)

- Creswell 1 FrameworkDocument26 paginiCreswell 1 FrameworkHemaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SEB104 - Research EssayDocument3 paginiSEB104 - Research EssayGÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conflict Across CulturesDocument15 paginiConflict Across CulturesAnkaj MohindrooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arato 1972 Lukacs Theory of ReificationDocument42 paginiArato 1972 Lukacs Theory of ReificationAnonymous trzOIm100% (1)

- Stewartk Edid6503-Assign 3Document10 paginiStewartk Edid6503-Assign 3api-432098444Încă nu există evaluări

- SLM GM11 Quarter2 Week9Document32 paginiSLM GM11 Quarter2 Week9Vilma PuebloÎncă nu există evaluări

- MTBMLE-theory and Rationale-Vanginkel PDFDocument21 paginiMTBMLE-theory and Rationale-Vanginkel PDFALMA R. ENRIQUEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Process and Personality PDFDocument311 paginiProcess and Personality PDFrezasattariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chytry, Josef. 2014. Review of Aesthetics of Installation Art, by Juliane Rebentisch. - The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism PDFDocument20 paginiChytry, Josef. 2014. Review of Aesthetics of Installation Art, by Juliane Rebentisch. - The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism PDFMilenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Listening For Memories Attentional Focus Dissociates Functional Brain NetwDocument20 paginiListening For Memories Attentional Focus Dissociates Functional Brain NetwAlexander SpiveyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handout - Kolodny, Philosophy 115 (UC Berkeley)Document4 paginiHandout - Kolodny, Philosophy 115 (UC Berkeley)Nikolai HamboneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Organizational Behavior Human Behavior at Work Thirteenth EditionDocument25 paginiOrganizational Behavior Human Behavior at Work Thirteenth EditionAbigail Valencia MañalacÎncă nu există evaluări

- 640 Balanced Literacy Lesson Plan FinalDocument2 pagini640 Balanced Literacy Lesson Plan Finalapi-260038235Încă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 12 PhenomologyDocument18 paginiLesson 12 PhenomologyKaryl Dianne B. LaurelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motivation Across CulturesDocument21 paginiMotivation Across CulturesSana SajidÎncă nu există evaluări

- OLAES - Athenian EducationDocument23 paginiOLAES - Athenian EducationpamelaÎncă nu există evaluări