Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Psychoanalytic Theory As A Unifying Framework For 21ST Century Personality Assessment

Încărcat de

Paola Martinez Manriquez100%(1)100% au considerat acest document util (1 vot)

304 vizualizări20 paginiartículo sobre el pscoanalisis y sus usos

Titlu original

PSYCHOANALYTIC THEORY AS A UNIFYING FRAMEWORK FOR 21ST CENTURY PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentartículo sobre el pscoanalisis y sus usos

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

100%(1)100% au considerat acest document util (1 vot)

304 vizualizări20 paginiPsychoanalytic Theory As A Unifying Framework For 21ST Century Personality Assessment

Încărcat de

Paola Martinez Manriquezartículo sobre el pscoanalisis y sus usos

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 20

PSYCHOANALYTIC THEORY AS A

UNIFYING FRAMEWORK FOR 21ST

CENTURY PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

Robert F. Bornstein, PhD

Adelphi University

Psychoanalysis represents a valuable unifying framework for 21st century

personality assessment, with the potential to enhance both research and clinical

practice. After reviewing recent trends in psychological testing I discuss how

psychoanalytic principles can be used to conceptualize and integrate personality

assessment data. Research from three domainsthe role of projection in shap-

ing Rorschach responses, contrasting patterns of gender differences in self-

report and free-response dependency measures, and the use of process dissoci-

ation procedures to illuminate test score convergences and divergences

illustrates how psychoanalytic concepts may be combined with ideas and

ndings from other areas of psychology to offer unique insights regarding

assessment-based personality dynamics.

Keywords: psychoanalysis, psychoanalytic, personality assessment, Rorschach,

self-report

Although most people associate clinical psychology primarily with psychotherapy, per-

sonality assessments history is at least as long as that of psychological treatment. The rst

formal use of the term mental test (Cattell, 1890) occurred just before Freud published his

initial psychoanalytic writings (Breuer & Freud, 1896/1955); a century later personality

assessment continues to play a major role in structuring treatment and guiding research.

Moreover, unlike many clinical activities, personality assessment is a uniquely psycho-

logical endeavor. As Groth-Marnat (1999) pointed out, there are at least 35 different

categories of mental health professionals who treat mental disorders, but only psycholo-

gists are trained and qualied to conduct personality assessments.

Clinicians often use the terms diagnosis and assessment interchangeably, but in fact

these terms mean very different things. Diagnosis involves identifying and documenting

Robert F. Bornstein, PhD, Derner Institute of Advanced Psychological Studies, Adelphi University.

Portions of this paper were presented at the annual meeting of the Rapaport-Klein Study Group,

Stockbridge, MA; June 14, 2008.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Robert F. Bornstein, PhD,

Derner Institute of Advanced Psychological Studies, 212 Blodgett Hall, Adelphi University, Garden

City, NY, 11530. E-mail: bornstein@adelphi.edu

Psychoanalytic Psychology 2010 American Psychological Association

2010, Vol. 27, No. 2, 133152 0736-9735/10/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0015486

133

a patients symptoms to classify that patient into one or more categories whose labels

represent shorthand descriptors of psychological syndromes (e.g., bulimia nervosa, schiz-

oid personality disorder). Assessment, in contrast, involves administering one or more

personality tests (and sometimes intellectual and neuropsychological tests as well) to

disentangle the complex array of dispositional and situational factors that combine to

determine a patients subjective experiences, core beliefs, emotional patterns, motives,

traits, defenses, and coping strategies. Put another way, diagnosis is key to understanding

a patients pathology; assessment is key to understanding the person with this pathology.

Framed in this manner, it becomes clear that personality assessment isor should

bea task strongly inuenced by psychodynamic principles. After all, personality as-

sessment not only involves describing a patients surface presentation, but also requires

the assessor to draw conclusions regarding underlying dynamics that shape this presen-

tation. Moreover, in addition to documenting convergences between patterns obtained on

different psychological assessment tools, personality assessment identies divergences as

wellinstances wherein the patient produces contrasting patterns (or discontinuities) on

measures that tap different domains of experience (e.g., self-report vs. free-response tests;

see Bornstein, 2002; Meyer et al., 2001).

1

During the middle decades of the 20th century, personality assessment was in fact

shaped primarily by psychoanalytic concepts (see Holt, 1966; Klopfer, 1960; Mayman,

1959; Rapaport, Gill & Schafer, 1945, 1968; Schafer, 1954), with the understanding that

patients often had limited insight into underlying motives and conicts, so administration

of an array of measures using diverse methods to tap different levels of functioning was

critical. That era has ended. In most inpatient and outpatient settings today personality

assessment consists primarily of the administration and interpretation of self-report tests

whose theoretical underpinnings are decidedly unanalytic (e.g., the Beck Depression

Inventory [Beck & Steer, 1993], the Personality Assessment Inventory [Morey, 2003]).

When free-response tests such as the Rorschach Inkblot Method (RIM) are employed, they

are typically scored and interpreted using systems that emphasize actuarial scoring of

structural features (e.g., Exners, 1991, Comprehensive System) in lieu of the traditional

psychodynamic emphasis on content. Even in psychoanalytic training institutes interest in

psychological assessment has declined, and few analytic candidates now receive system-

atic training in the administration and interpretation of personality tests. Most analytic

practitioners do little or no formal psychological assessment as part of their clinical

practice (cf., Gabbard, 2000; Huprich, 2009).

Despite these challenges, in recent years clinicians and researchers have attempted to

strengthen connections between psychodynamic principles and personality assessment.

For example, Handler and Hilsenroth (1998) reviewed the myriad ways in which psy-

choanalytic ideas can be used to interpret the results of psychological tests from a variety

of domains (e.g., intellectual tests, self-report questionnaires, free-response measures,

gure drawings, neuropsychological screens). Sugarman and Kanner (2000) described

four functions that psychoanalytic theory brings to psychological testing: (a) an organizing

function; (b) an integrative function; (c) a clarifying function; and (d) a predictive function

1

Because the degree to which projection plays a role in shaping responses to ambiguous

stimuli like Rorschach inkblots and Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) cards remains controversial,

I use the term free-response test rather than projective test to describe these instruments (see Meyer

& Kurtz, 2006, for a detailed discussion of this issue). Although Bornstein (2007c) recently

proposed that the term free-response test be replaced with the more precise label stimulus attribution

test, this new terminology has not yet been widely adopted.

134 BORNSTEIN

(see also Sugarman, 1991, 1992). Most recently Bornstein and Masling (2005) identied

seven well-validated, clinically useful RIM scoring and interpretation systems, each of

which is based, in whole or in part, on psychodynamic principles.

The purpose of this article is to contribute to the ongoing dialogue regarding the value

of psychoanalytic theory in psychological testing. I argue that psychoanalysis represents

a valuable unifying framework for 21st century personality assessment, with the potential

to enhance both research and clinical practice. I begin by reviewing recent trends in

personality assessment, then discuss how psychoanalytic constructs can be used to help

conceptualize personality assessment data. Drawing upon research using self-report and

free-response measures of interpersonal dependency, I offer examples from three do-

mainsthe role of projection in shaping RIM responses, contrasting patterns of gender

differences in self-report and free-response dependency measures, and the use of process

dissociation procedures to illuminate test score convergences and divergencesto show

how psychoanalytic principles may be combined with ideas and ndings from other areas

of psychology to offer unique insights regarding personality dynamics.

Recent Trends in Personality Assessment

Contemporary personality assessment is characterized by a number of features that

simultaneously reduce the quality of empirical research in this area and undermine the

appropriate use of assessment data in clinical settings. Four stand out.

A Near-exclusive Focus on Self-report

Several decades ago, psychological assessment almost invariably included a comprehensive

test battery consisting of measures designed to tap different domains of adaptation (e.g., trait

scales and intellectual tests), and different levels of functioning and experience (e.g., ques-

tionnaires and free-response measures; see Allison, Blatt, & Zimet, 1968; Rapaport et al.,

1945, 1968). Attributable in part to the demands of managed care (Sperling, Sack, & Field,

2000), and in part to the dominance of atheoretical, descriptive approaches to personality such

as the ve-factor model (McCrae & Costa, 1997), assessment now consists primarily of the

administration, scoring, and interpretation of questionnaires.

Equating Self-report of a Construct With the

Underlying Construct

Exclusive reliance on self-reports, in and of itself, limits the inferences that may be drawn from

personality test data; this situation is exacerbated by the fact that in both research and clinical

settings, self-reports of traits and symptoms are often conceptualized as veridical indices of these

traits and symptoms. The equating of self-report with actual behavior occurs even for those domains

wherein lack of insight is regarded as a hallmark of the construct being assessed (e.g., personality

pathology). When Bornstein (2003) conducted a systematic survey of personality disorder research

published in ve major journals between 1991 and 2000, he found that over 80% of published

studies relied exclusively on self-report data (only 4% assessed oberservable behavior).

2

2

Personality researchers are not alone in their overreliance on self-reports. In fact, a systematic

survey of articles published in psychologys seven most widely subscribed journals indicated that

questionnaire outcome measures were used in 65% of all published studies, ranging from a low of 37%

in Developmental Psychology to a high of 93% in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

(Bornstein, 2001a). Overreliance on self-report data is a pervasive problem in contemporary psychology.

135 PSYCHOANALYSIS AND PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

Overemphasis on Test Score Convergence

Following the tradition established by Campbell and Fiske (1959), personality assessment

research has focused primarily on documenting the convergence of scores on different

measures of the same construct, even when the measures use very different methods to

quantify these constructs (see Messick, 1995). However, as several researchers have

noted, scales that employ markedly different formats should show only modest test score

intercorrelation (Archer & Krishnamurthy, 1993a, 1993b; Meyer, 1996, 1997). Moreover,

test score divergence for measures that use different methods to measure similar con-

structs can be as informative and meaningful as test score convergence, sometimes more

so (Bornstein, 2002; Meyer et al., 2001).

Shifts in Personality Assessment Training

Given these trends, it is not surprising that the attention given to nontraditional personality

assessment methods in graduate-level assessment courses has declined in recent years,

with a concomitant increase in time devoted to self-report tests (Stedman, Hatch, &

Schoenfeld, 2001). When Childs and Eyde (2002) surveyed the curricula of 84 clinical

doctoral programs, they found that only 44% included a required course in personality

assessment, with most of these courses emphasizing self-report instruments. When Pi-

otrowski and Belter (1999) surveyed directors of 84 American Psychological Association-

approved predoctoral internship programs, the only area of assessment that had dimin-

ished in emphasis during the preceding ve years was free-response (e.g., Rorschach)

testing.

Psychoanalytic Theory as a Unifying Framework for 21st Century

Personality Assessment

Pedagogical and economic (e.g., managed care) issues notwithstanding, a key factor in the

shift from integrative, multimodal personality assessment to assessment based primarily

on self-report test data has been the absence of a unifying framework within which

psychologists may conceptualize and integrate information from different personality

assessment instruments. Psychoanalytic theory represents the most useful overarching

framework, for three reasons.

A Focus on Process

To a greater extent than other theoretical models, psychoanalysis focuses on the psycho-

logical processes that occur as individuals respond to internal stimuli (e.g., memories,

thoughts, emotions) and external events (e.g., novel experiences, familiar and unfamiliar

people, personality test items). In part these processes are shaped by the individuals

coping and defense style (Cramer, 2000, 2006; Lerner, 2005), but psychoanalytic theorists

and researchers have also examined how the processing of informationeven neutral,

conict-free informationis shaped by individual traits, motives, and need states (see

Erdelyi, 1985; Weinberger & McClelland, 1990). Many of these analyses are derived from

Hartmanns classic concept of conict-free spheres of the ego (see Hartmann, 1964), but

in recent years relational psychoanalysts have explored the ways in which language

affords shared meaning and consensus between analyst and analysand, revealing aspects

of underlying psychological process that would otherwise remain hidden (see Laplanche

& Pontalis, 1974, and Stern, 2004, for discussions of intersubjectivity in relational

psychoanalysis).

136 BORNSTEIN

Psychodynamic models are also unique in articulating the role that underlying psychic

structures play in personality development and dynamics. For example, psychoanalytic

theorists have described the ways in which mental representations of self and signicant

others (sometimes referred to as introjects or schemas) inuence motives, thought pat-

terns, and emotional reactions (Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983). Theorists and researchers

have also explored the impact of variations in infant-caregiver mirroring on personality

development and emotion regulation (Kohut, 1971; see also Beebe & Lachmann, 2002).

Most recently psychodynamic principles have been integrated with ndings from neuro-

imagery (e.g., functional magnetic resonance imaging) studies to delineate links between

cortical activity patterns and psychological processes such as memory distortion, confab-

ulation, and the retrieval of formerly inaccessible memories (see Gallo, Kensinger, &

Schacter, 2006).

Multiple Levels of Awareness

Psychoanalytic theory is unique in the degree to which it has developed formal models

describing the ways in which individuals process information on multiple levels, and with

contrasting degrees of awareness. The most inuential such perspective is derived from

Freuds (1900/1953) topographic model, which conceptualizes human information pro-

cessing in terms of three broad domains (conscious, preconscious, and unconscious), but

the topographic model is not the only framework used by psychoanalysts to conceptualize

the interplay of conscious and unconscious mental processes. In recent years other

complementary and competing psychodynamic conceptualizations of levels of awareness

in information storage and processing have emerged (e.g., Epstein, 1998; Erdelyi, 2006;

Westen, 1998). These alternative conceptualizations help illuminate the ways in which

cognitive and affective information is transformed as it emerges into consciousness

(Bucci, 1997, 2000), and the unique inuence of material that is neither fully conscious

nor completely unconscious, but exists on the fringes of consciousness (see Pyszczyn-

ski, Greenberg, & Solomon, 2000). Psychodynamic researchers have examined the role of

the self-representation in distinguishing memories accessible to conscious awareness from

those that are not, and the manner in which information may be processed on multiple

levels simultaneously (Bargh & Morsella, 2008). With respect to this latter issue, Erdelyi

(2004, 2006) has articulated in detail the psychological processes and situational variables

that underly temporal shifts in awareness as stimuli move among different levels of

consciousness.

Introspection Versus Experience

From its inception, a core tenet of psychoanalytic theory has been that individuals have

limited introspective access, so it is important to distinguish the persons private, subjec-

tive experience from his or her ability to turn attention inward and describe that experience

(Bornstein, 1993, 1999; Stern, 2004). Many techniques in psychodynamic therapy are

directed toward increasing introspective access and making unconscious material con-

scious. These include Freuds traditional free association method, dream analysis, and

other strategies for inducing hypermnesia for previously inaccessible memories (Erdelyi,

1985; Sperling et al., 2000). In this context psychodynamic theorists have discussed the

value of deconstructing core conictual relationship themes as a method for increasing

introspective awareness (Luborsky & Crits-Christoph, 1990); other clinicians emphasize

the value of transference (and countertransference) analysis to uncover aspects of private

experience that would otherwise remain hidden (see Weiner & Bornstein, 2009).

137 PSYCHOANALYSIS AND PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

As Bornstein (2002) and others (e.g., Huprich, 2009; Meyer et al., 2001) have pointed

out, exploration of divergences between information that is accessible via introspection

and information that shapes behavior reexively and mindlessly can yield important

information regarding underlying personality structure, coping, and defense (see also

McClelland, Koestner, & Weinberger, 1989). Because certain personality tests (e.g.,

self-report scales) are designed to tap the end-products of testees introspective efforts

whereas others (e.g., free-response measures) tap experience more than introspection, a

psychodynamic perspective is particularly useful in contrasting and combining the results

of self-report and free-response test data.

Toward a More Unied Unifying Framework: Integrating Psychoanalysis With

Other Areas of Psychology

As several researchers have noted (e.g., Bornstein, 2005; Bucci, 2000; Masling, 1990), a

central challenge confronting psychoanalytic theorists and practitioners today involves

integrating into their ideas and therapeutic techniques ndings from other areas of

psychology. For example, psychodynamic models of memory and information processing

are enhanced when they incorporate concepts from cognitive science (e.g., Bargh &

Morsella, 2008; Campanella & Belin, 2007). Psychoanalytic writings on the perception of

self and others benet from attention to social psychological research on this topic

(Kammrath, Mendoza-Denton, & Mischel, 2005; Newman, Duff, & Baumeister, 1997).

The psychoanalytic literature is replete with examples of constructs that conict with

well-established empirical ndings in neighboring elds (Bornstein, 2001b), and analysts

tendency to ignore nonanalytic writings has led to the wholesale co-opting and reinvention

of some seminal psychoanalytic concepts by researchers in other areas (Bornstein, 2005).

Thus, a truly unied unifying framework must not only draw upon psychoanalytic

principles, but should also embed these principles in a nomological network of nomothetic

research ndings from outside psychoanalysis. In the following sections, I combine an

overarching psychoanalytic perspective with ideas and ndings from social, developmen-

tal, and cognitive psychology to illustrate the ways in which psychoanalytic theory can be

used to conceptualize and integrate personality assessment data.

Integrating Psychodynamic and Social Perspectives:

Projection in the Rorschach

Although most psychologists (analysts included) conceptualize projection primarily as a

means by which people disavow and externalize undesired feelings and impulses, Freud

(1913/1955) made clear that projection is both a defensive strategy and a method for

structuring external perceptions and inferences. Thus, Freud (1913/1955, p. 64) wrote:

Projection . . . . also occurs where there is no conict. Under conditions whose nature has not

been sufciently established internal perceptions of emotional and thought processes can be

employed for building up the external world, though they should by rights remain part of the

internal world.

There have been surprisingly few attempts to document empirically the role that

projection may play in shaping Rorschach responses (Exner, 1989; Murstein, 1956;

Murstein & Wolf, 1970; Porcelli & Meyer, 2002), and each of these studies produced

inconclusive results. These ambiguous ndings did not stem from faulty empirical

138 BORNSTEIN

methods, but from an exclusive focus on outcome, assessed using correlational designs

(i.e., an exclusive emphasis on quantifying RIM score-external criterion links). By

combining psychoanalytic principles with models of social projection (e.g., Newman et

al., 1997) it is possible to understand more completely the mental operations that occur as

people disavow undesired traits and use internal perceptions and predispositions to

structure external stimuli.

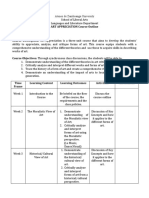

Figure 1 illustrates the sequence of psychological processes that leads to projection of

an undesired trait. As this gure suggests, when people are faced with evidence they might

possess a trait they would rather not see in themselves (e.g., hostility, dependency,

narcissism), they try to avoid thinking about this trait. When trait-relevant thoughts

emerge into consciousness, the person attempts to suppress these thoughts, and push them

out of awareness (Newman et al., 1997; Schimel, Greenberg, & Martens, 2003). Over

time, this ongoing avoidance/suppression process leads to two results: one intended, one

unintended. On the positive side, vigilant avoidance of thoughts related to an undesired

trait enables people to maintain the (conscious) belief that they do not possess this trait.

On the negative side, however, frequent suppression of thoughts regarding an undesired

trait renders this trait chronically accessible (Wegner & Erber, 1992). Research has shown

that chronically accessible traits are easily primed (i.e., brought into working memory)

when the suppressor perceives behavior in others that resembleseven remotelythe

undesired trait (see Bargh, 1994; Higgins & King, 1981).

In considering the implications of this avoidance/suppression dynamic for personality

assessment, it is important to note that suppression-based misperceptions are not limited

to social contexts. Although we are predisposed to overperceive undesired traits and

motives in other people, in part because we devote considerable cognitive resources to

inferring others intentions and motives (Maner et al., 2005; Schimel et al., 2003), we may

Conscious Perception

Of Self as Not

Evidence of Avoidance and Possessing Undesired

Undesired Suppression of Trait

Trait in Trait-Related

Oneself Thoughts Chronic Accessibility

Of Undesired Trait

Overperception of

Undesired Trait in

Others (people,

animals, abstract

entities)

Figure 1. Projection from a socialcognitive perspective. According to this view, avoidance

and suppression of thoughts related to an undesired trait will lead to chronic accessibility of

trait-related concepts and a tendency to misattribute the unwanted trait to others. Originally

published as Figure 1 in Might the Rorschach be a Projective Test After All? Social

Projection of an Undesired Trait Alters Rorschach Oral Dependency Scores by Robert F.

Bornstein (Journal of Personality Assessment, Volume 88, pages 354367). Copyright 2007

by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

139 PSYCHOANALYSIS AND PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

also misattribute undesired traits (e.g., hostility) to nonhuman organisms (e.g., shy cats,

stray dogs), or even abstract entities (e.g., the government). A suppressed trait concept,

once primed, nds expression in myriad ways.

Using this framework, Bornstein (2007a) explored the effects of undesired trait

feedback on Rorschach Oral Dependency (ROD) scores (see Bornstein & Masling, 2005,

for a review of evidence on the validity of ROD scores as an index of implicit dependency

strivings). To begin, a large sample of introductory psychology students completed the

ROD scale, along with the Interpersonal Dependency Inventory (IDI), a widely used

self-report measure of dependency (Hirschfeld et al., 1977). Students who obtained very

low or very high IDI scores were then called back for a follow up session by an

experimenter unaware of these students ROD scores. When these high-IDI and low-

IDI students arrived at the laboratory they were told they were taking part in a study of

personality and self-perception. Then came the key manipulation: Half the high-IDI

participants and half the low-IDI participantsthose in the dependent feedback condi-

tionwere told that they had in fact obtained very high dependency scores during the

earlier prescreening. They were shown a printout illustrating their dependent personality

prole, and while they viewed this printout they received verbal feedback from the

experimenter (see Bornstein, 2007a, p. 359), who said:

These are your percentile scoreshow high you scored on each scale relative to other college

students. Your highest score was on the insecurity scale. Your other high scores are on the

vulnerability and low self-condence scales, and you also scored somewhat high on the reliance

on others scale. These scores indicate that youre a dependent person, and insecure in social

situations.

The other half of the participants received control feedback, where they were shown

a low dependent printout and told:

These are your percentile scoreshow high you scored on each scale relative to other college

students. You didnt score high on any of the scales, which indicates that youre basically an

independent person, and condent in social situations. As you can see your scores on these

subscales are right in line with the norms.

After receiving either dependent or control feedback each participant completed

the ROD scale again, so their post-feedback scores could be compared with their

scores from the initial screening.

The central results of this experiment are summarized in Figure 2, and as this gure

shows, the only participants who showed a signicant increase in dependent Rorschach

imagery from Time 1 to Time 2 were those who: (1) initially described themselves as

autonomous and independent on the IDI; then (2) received feedback that indicated that

they were actually insecure and highly dependent. Participants who received control

(irrelevant) feedback showed no ROD increase (regardless of their IDI scores), nor did

participants in the dependent feedback condition who initially had elevated IDI scores

(having described themselves at Time 1 as being highly dependent). Apparently being told

we possess a trait wed rather not see in ourselves really does cause us to overperceive this

trait in things around useven in inkblots. Thus, combining psychodynamic principles

with ideas and methods from social psychology helped generate the rst direct evidence

that a projection-like dynamic shapes Rorschach responses, at least under certain condi-

tions. Additional studies are needed to determine the generalizability of these patterns to

other Rorschach scoring dimensions.

140 BORNSTEIN

Integrating Psychodynamic and Developmental

Perspectives: Gender and Gender Role

Who shows higher overall levels of interpersonal dependency, women or men? When

asked, psychologists (e.g., Cadbury, 1991) and laypersons (Bornstein, Rossner, Hill,

& Stepanian, 1994) respond similarly, believing that in general, women are more

dependent. A meta-analysis of research on gender differences in self-report depen-

dency tests (Bornstein, 1995) produced results consistent with the widespread per-

ception that women show higher levels of expressed dependency: Women scored

higher than men on every self-report measure wherein gender differences have been

assessed (N of comparisons 94), and when these gender differences were combined

statistically women obtained self-report dependency scores that exceeded those of

men by .41 standard deviations (d .41, combined z 19.22, p .000001). These

results are summarized in the top portion of Table 1.

A very different pattern emerged for free-response dependency scales. In most

individual studies women and men produced comparable free-response dependency

scores, but when these data were combined using meta-analytic techniques (N of

comparisons 26), men actually showed higher levels of underlying dependency than

1

2

3

4

5

6

2 E M I T 1 E M I T

TIME OF TESTING

R

O

D

S

C

O

R

E

High IDI, Dependent Feedback

Low IDI, Dependent Feedback

High IDI, Irrelevant Feedback

Low IDI, Irrelevant Feedback

Figure 2. Effects of Interpersonal Dependency Inventory (IDI) score (high vs. low),

feedback condition (dependent vs. irrelevant), and time of testing (Time 1 vs. Time 2) on

ROD scale scores. Adapted from Table 2 in Might the Rorschach be a Projective Test After

All? Social Projection of an Undesired Trait Alters Rorschach Oral Dependency Scores by

Robert F. Bornstein (Journal of Personality Assessment, Volume 88, pages 354367).

Copyright 2007 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

141 PSYCHOANALYSIS AND PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

did women (d .11, combined z 1.93, p .05). These patterns are summarized in the

bottom portion of Table 1. A d of .11 (approximately one-ninth SD) might seem modest, and

it is indeed considered a small effect size (Cohen, 1988). However, a d of this magnitude is

not trivial, and exceeds the effect sizes associated with the impact of a daily aspirin

regimen in reducing heart attack risk in men (d .02), and the effect of chemotherapy on

enhanced likelihood of recovery from breast cancer in women (d .03). This d is also

larger than that linking tobacco use with increased risk for developing lung cancer (d

.08), and is identical to the effect size associated with combat exposure and PTSD risk in

Vietnam veterans (see Meyer et al., 2001, for a listing of representative effect sizes in

psychology and medicine).

How can we understand these contrasting patterns of gender differences in

self-report and free-response dependency tests? Consistent with psychodynamic mod-

els of early childhood development (Beebe & Lachmann, 2002; Galatzer-Levy &

Cohler, 1993; Russ, 1996; Silverstein, 2007), McClelland et al. (1989, pp. 698699)

argued that free-response tests provide a more direct readout than do self-

reports. . ..because implicit motives are built on early, prelinguistic affective experi-

ences whereas self-attributed motives are built on explicit teaching by parents and

others as to what values or goals it is important for a child to pursue. Supporting

McClelland et al.s theoretical conceptualization, in a subsequent meta-analysis

Table 1

Gender Differences in Dependency: Self-report Versus Free-response Measures

Measure

Number of

effect sizes

Combined effect

size (d)

Combined

z p

Self-report measures

DEQ 18 .37 8.13 .00001

IDI 16 .42 6.20 .00001

Dy Scale 12 .50 10.91 .00001

MCMI 8 .46 5.29 .00001

DP Scale 7 .39 5.03 .00001

EPPS 5 .48 3.98 .0001

SAS 4 .60 4.42 .00001

LKDOS 3 .61 3.38 .0005

PDQ-R 2 .16 0.90 NS

Other 20 .33 7.17 .00001

Free-response measures

ROD 17 .17 2.08 .02

TAT 3 .09 0.74 NS

HIT 2 .17 0.54 NS

Other 4 .07 0.12 NS

Note. DEQ Depressive Experiences Questionnaire Dependency Scale; IDI Interpersonal Dependency

Inventory; Dy Scale MMPI Dependency Scale; MCMI Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory Dependency

Scale; DP Scale Dependence Proneness Scale; EPPS Edwards Personal Preference Survey Succorance

Scale; SAS Sociotropy-Autonomy Scale; LKODS Lazare-Klerman Oral Dependency Scale; PDQ-R

Personality Disorder Questionnaire-Revised Dependency Scale; NS not signicant; ROD Rorschach Oral

Dependency Scale; TAT Thematic Apperception Test Dependency Scale; HIT Holtzman Inkblot Test

Dependency Scale.

Adapted from Table 1 in Sex Differences in Objective and Projective Dependency Tests: A Meta-Analytic Review

by Robert F. Bornstein (Assessment, Volume 2, pages 319331). Copyright 1995 by Psychological Assessment

Resources, Inc.

142 BORNSTEIN

Bornstein, Bowers, and Bonner (1996b) found signicant positive correlations be-

tween self-reported dependency and femininity, and signicant negative correlations

between self-reported dependency and masculinity, in both women and men. Free-

response dependency scores were unrelated to gender role orientation regardless of

participant gender.

These patterns suggest that gender differences in self-reported dependency are, at

least in part, the product of womens and mens efforts to present themselves in

gender-consistent ways on psychological tests.

3

But what accounts for the higher

levels of implicit dependency in men relative to women? Self-presentation cannot

account for these results, and two possibilities seem plausible. First, it may be that

men simply experience stronger underlying dependency strivings than do women,

with certain masculine attitudes and behaviors representing a sort of reaction forma-

tion against feelings of helplessness and vulnerability, a possibility that has been

raised by both psychoanalytic (Coen, 1992; Fuerstein, 1989) and feminist (Gilbert,

1987; Lerner, 1983) theorists. Alternatively, it may be that mens efforts to conceal

dependent urges and feelings cause these unexpressed urges to build up and reveal

themselves indirectly on free-response tests. Such an interpretation would be consis-

tent with Bornsteins (2007a) ndings regarding the impact of avoidance and sup-

pression of self-relevant information on Rorschach responding (see also Wegner &

Erber, 1992), but a denitive test of this interpretation of gender differences in

dependency has not yet been conducted.

Integrating Psychodynamic and Cognitive Perspectives:

Process Dissociation

Psychoanalytic theory provides a unique perspective on cross-method inconsistencies in

psychological test data because, alone among theoretical models of personality, psycho-

analysis explicitly links the degree of structure provided by different assessment tools with

personality factors (e.g., impulse control, reality testing) that should lead to differential

performance on more versus less structured tests. For example, psychoanalytic researchers

have found that patients with borderline pathology often perform quite well on measures

with a high degree of structure (e.g., intelligence tests) while performing poorly on

unstructured instruments like the Rorschach (Carr & Goldstein, 1981). Along somewhat

different lines, Bornstein (1998) demonstrated that individuals with dependent personality

disorder traits and symptoms scored high on both self-report and free-response measures

of interpersonal dependency whereas individuals with histrionic personality disorder traits

and symptoms obtained high free-responsebut low self-reportdependency scores (see

Bornstein, 1998, for a discussion of the implications of these ndings for the psychody-

namics of dependent and histrionic personality pathology).

To date, most investigations of test score inconsistency have contrasted performance

across two or more instruments in a particular patient group (Carr & Goldstein, 1981),

and/or contrasted the performance of two or more participant groups for a particular subset

of assessment tools (Bornstein, 1998). By integrating into these studies experimental

manipulations designed to alter one set of test scores but not the other, researchers can

learn more about the psychological processes engaged by different assessment instru-

ments, and draw rmer conclusions regarding the dispositional and situational factors that

3

See Goffman (1959) for the classic sociological analysis of strategic self-presentation, and

Higgins and Pittman (2008) for a contemporary psychological discussion of this phenomenon.

143 PSYCHOANALYSIS AND PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

lead to test score discontinuities. The rst step involves understanding as fully as possible

the phenomenology of self-report and free-response teststhe private, subjective expe-

riences of test-takers as they respond to different types of test items.

Consider the following two items from the IDI: I would rather be a follower than a

leader, and I have a lot of trouble making decisions by myself. Both statements are

rated by the testee on Likert-type scales anchored by the terms not at all true of me and

very true of me. At least three psychological processes occur as people respond to these

IDI items. First, testees engage in introspection, turning their attention inward to deter-

mine whether the statement captures some aspect of their feelings, thoughts, motives, or

behaviors. Second, a retrospective memory search occurs, as testees attempt to retrieve

instances wherein they experienced or exhibited the response(s) described in the test item.

Finally, testees may engage in deliberate self-presentation, deciding whether, given the

context and setting in which they are being evaluated, it is better to answer honestly, or

modify their response to depict themselves in a particular way. Typically these efforts are

aimed at faking good (i.e., attempting to portray oneself as healthier than is actually the

case) or faking bad (attempting to portray oneself as unhealthy and exaggerate pathol-

ogy), depending upon the testees self-presentation goals.

Contrast this set of psychological processes with those that occur as people complete

the ROD scale. Here the testee is asked to provide responses to the 10 Rorschach inkblots;

these responses are then scored to derive the overall proportion of oral and dependent

imagery contained in the percepts (Bornstein & Masling, 2005). Unlike the IDI, the

fundamental challenge for an individual completing the ROD scale is to create meaning

in a stimulus that can be interpreted in multiple ways. To do this testees must direct their

attention outward (rather than inward), and focus on the stimulus (not the self); they then

attribute meaning to the stimulus based on properties of the inkblot and the associations

primed by these stimulus properties. Once a series of potential percepts (or stimulus

attributions) is formed testees typically sort through these possible responses, selecting

some and rejecting others before providing their description (see Exner, 1991, and Weiner,

2004, for general overviews of stages in Rorschach responding, and Bornstein, 2007a, for

stages involved in generating ROD scores).

With this as context, Bornstein (2002) utilized ideas and ndings from cognitive

psychologists who employ experimental manipulations to disentangle the psychological

and neurological underpinnings of implicit versus explicit memory (e.g., Jacoby & Kelley,

1991; Schacter, 1987), combining these ideas with psychoanalytic principles to develop

the process dissociation approach to personality assessment. The process dissociation

strategy involves identifying naturally occurring inuences on test scores (e.g., testee

motivation or mood state) then deliberately manipulating these inuences to illuminate

underlying response processes.

In the rst study using this approach, Bornstein et al. (1994) administered the IDI and

ROD scale to a large, mixed-sex sample of college students under three different

conditions. One-third of the participants completed the two measures under a negative set

condition; prior to completing the IDI and ROD scale these participants were told that

both were measures of interpersonal dependency, and that the study was part of a program

of research examining the negative aspects of dependent personality traits (following

which several negative consequences of high levels of dependency were described).

One-third of the participants completed the two measures under a positive set condition;

these participants were told that the study was part of a program of research examining the

positive, adaptive aspects of dependency (following which several positive features of

dependency were described). The remaining participants completed the two measures

144 BORNSTEIN

under standard conditions, wherein no mention is made of the purpose of either scale, or

the fact they assess dependency.

Bornstein et al. (1994) found that relative to the baseline (control) condition, partic-

ipants IDI scores increased signicantly in the positive set condition, and decreased

signicantly in the negative set condition; ROD scores were unaffected by instructional

set. These patterns reect the contrasting processes that occur as participants complete the

IDI (introspection, retrospection, deliberate self-presentation) and the ROD scale (atten-

tion directed outward, focus on stimulus rather than self, attribution of meaning to

ambiguous inkblots), and illustrate the utility of the process dissociation approach in

delineating the factors that lead to self-report/free-response test score discontinuities. In a

follow-up investigation Bornstein, Bowers, and Bonner (1996a) examined the impact of

induced mood state on IDI and ROD scores, asking participants to write essays regarding

traumatic events, joyful events, or neutral events to induce a corresponding mood

immediately prior to testing. Bornstein et al. (1996a) found that, as expected, induction of

a negative mood prior to testing led to a signicant increase in RODbut not IDIscores

(see Bornstein, 2002, and Cogswell, 2008, for descriptions of these and other process

dissociation studies involving self-report and free-response dependency scales).

Discussion

The present review illustrates the utility of psychodynamic principles in illuminating the

psychological processes that underlie free-response tests in elucidating the effects of

naturally occurring variables (e.g., gender role) on personality test data, and in contrasting

and integrating results from different personality assessment tools. Although these initial

studies all involved the assessment of interpersonal dependency, the principles and

strategies that guided these investigations should generalize to other traits as well (e.g.,

impulsivity, narcissism, need for achievement; see Craig, Koestner, & Zuroff, 1994, and

Koestner, Weinberger, & McClelland, 1991, for examples). Studies conducted to date

suggest that psychoanalysis can function as a unifying framework for integrative person-

ality assessment, and because the results of these investigations help inform clinicians and

researchers about the underlying dynamics that shape test responses, the reverse is also

true: Just as psychoanalysis represents a potential unifying framework for personality

assessment, integrative personality assessment represents a useful tool for studying

psychodynamic processes (see Handler & Meyer, 1998, and Sugarman & Kanner, 2000,

for discussions of this issue).

Askeptic might argue that although psychodynamic principles can be used to explain these

patterns, the present results may also be interpreted using alternative frameworks that do not

draw upon psychoanalytic concepts. For example, certain ndings described in this review

(e.g., gender differences in self-reportbut not free-responsedependency test scores)

might be attributable in part to self-presentation effects, reecting womens willingness

(and mens unwillingness) to acknowledge dependent attitudes, urges, and feelings.

Similarly, the impact of mood on free-response test data might reect the well-

documented priming effects of mood on affectively congruent memories.

Although certain ndings described herein can indeed be explained using alternative

frameworks, some cannot, and taken together these patterns are most parsimoniously

conceptualized in psychodynamic terms. For example, the impact of feedback regarding

disavowed traits on free-response test scores cannot be accommodated by a straightfor-

ward self-presentation model, and can only be fully explained within a framework that

145 PSYCHOANALYSIS AND PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

explains why unwanted and disavowed personal characteristics are externalized and

misattributed to objects in the environment. Other patterns (e.g., mens elevated score on

measures of implicit dependency strivings) also lend themselves readily to a psychody-

namic interpretation, and are not easily explained by competing models of personality and

psychopathology (e.g., cognitive, behavioral, humanistic). As discussed, three qualities

unique to psychoanalytic theoryits focus on process, on multiple levels of awareness,

and on introspection versus experiencecombine to create a context within which

personality test score convergences and divergences can be usefully interpreted, and

within which different forms of personality test data can be integrated. No other extant

model has these three qualities. Thus, although other theoretical frameworks (e.g.,

cognitive, behavioral, humanistic) can help explain specic personality test results and

particular test score interrelationships, only the psychodynamic model offers the kind of

overarching framework that allows the broad spectrum of ndings in this area to be

integrated within a single theoretical perspective.

As research on the utility of psychodynamic principles in conceptualizing and inte-

grating personality test data continues to accumulate results from these investigations can

begin to move from laboratory to clinic. Three guiding principles will help facilitate this

transition.

Principle 1: A Focus on Process Is Critical for

Effective Interpretation of Personality Assessment Data

As noted at the outset of this review, several distinguishing features of psychoanalytic

theory make this theory particularly useful in conceptualizing personality assessment data

(i.e., its focus on process, multiple levels of awareness, and introspection vs. experience).

As Meyer and Kurtz (2006) noted, integrating test data from measures that employ

different methods and formats has long been a compelling challenge for assessment

psychologists (cf., Archer & Krishnamurthy, 1993a, 1993b), in part because most validity

studies to date have focused on outcome (i.e., test score-criterion correlation) rather than

underlying process. A process-focused approach can help resolve some longstanding

questions in this area, and as Bornstein (2007c) noted, such an approach also allows

clinicians to make ner distinctions among (and derive more accurate descriptive labels

for) widely used personality assessment tools. For example, traditionally measures like the

Draw-a-Person test and Kinetic Family Drawing have been grouped with the RIM and

TAT under the broad heading of projective instruments, but scrutiny of the mental

processes that occur as testees complete these measures suggests that what were formerly

known as projective drawings are better described as constructive tests, while measures

like the RIM and TAT may be more accurately described as stimulus attribution tests (see

Bornstein, 2007c, Table 1, for a complete listing of personality tests by process-based

category).

Principle 2: Clinical and Laboratory Assessment

Studies Provide Complementary and

Synergistic Results

A key assumption of the process dissociation approach is that subtle, naturally occurring

inuences on test scores (e.g., testee motivation or mood state) can be used to illuminate

underlying response processes. Thus, a process focused model reconceptualizes test score

confounds (and threats to validity) as opportunities for insight into the psychological

dynamics that shape peoples responses to personality test items and stimuli. Put another

146 BORNSTEIN

way, the process dissociation strategy reverses the usual procedure for dealing with

potential test score confounds: Rather than attempting to minimize or eliminate these

confounds in the laboratory and in vivo (a difcult challenge as best; see Messick, 1995)

the researcher leans into them, exploits them, and deliberately manipulates them to

increase or decrease their impact and see how test results are affected. Although histor-

ically experimental methods have not played a primary role in testing psychoanalytic

hypotheses (Bornstein, 2007b), or in validating personality assessment tools (Bornstein,

2002), the process focused approach blends psychoanalytic concepts with nomothetic

research methods to obtain unique insights into underlying personality dynamics.

Principle 3: Personality Assessment Is Fundamentally

Analytic, but Personality Testing Is Behavioral

The present results suggest a fruitful convergence between psychodynamic and behavioral

principles in personality assessment. As Handler and Meyer (1998, pp. 45) noted in

contrasting psychological testing and psychological assessment:

Testing is a relatively straightforward process wherein a particular test is administered to

obtain a particular score or two. Subsequently, a descriptive meaning can be applied to the

score based on normative, nomothetic ndings. . . . Psychological assessment, however, is a

quite different enterprise. The focus here is not on obtaining a single score, or even a series

of test scores. Rather, the focus is on taking a variety of test-derived pieces of information,

obtained from multiple methods of assessment, and placing these data in the context of

historical information, referral information, and behavioral observations to generate a cohe-

sive and comprehensive understanding of the person being evaluated.

Put another way, psychological testing requires precision, objectivity, and the kind of

scientic detachment that facilitates accurate data-gathering. Psychological assessment

involves integration, synthesis, and clarication of ambiguouseven conicting

evidence obtained during the testing process.

Thus, the competent tester must be (at least for that moment) a staunch behaviorist,

understanding the contingencies that dene the testing situation and using this knowledge

to maximize the validity and generalizability of test data. Once these data are gathered the

behavioral tester must transform into a psychodynamically informed assessor, able to

combine dynamic concepts with research ndings from other areas of psychology to

interpret test results in the context of referral information, life history information, and

behavioral observations made during testing. Wachtel (1977, 1997) discussed the ways

that psychodynamic and behavioral principles can be combined to enhance the effective-

ness of insight-oriented psychotherapy; the present analysis suggests that the same may be

true of psychological assessment.

Conclusion

If a single theme cuts across the various issues taken up in this review, that theme is

integration. Not only does effective psychological assessment combine behavioral and

psychodynamic principles, but it also requires that the clinician integrate different types

of test data (e.g., self-report and free response), integrate psychoanalytic concepts with

ndings from other areas of psychology (e.g., social, cognitive), and integrate knowledge

regarding test score outcome (i.e., convergent validity) with information regarding the

psychological processes that occur as patients engage different tests. Ultimately person-

147 PSYCHOANALYSIS AND PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

ality test data must also be integrated with information that emerges over time during

treatment, and as this occurs some heretofore unnoticed aspects of the assessment results

may well turn out to be salienteven keypieces of evidence, enabling the clinician to

maximize therapeutic efcacy and gain a deeper understanding of the patients underlying

dynamics and surface presentation. Integration is a process that begins during assessment,

but continues through treatment and beyond.

References

Allison, J., Blatt, S. J., & Zimet, C. N. (1968). The interpretation of psychological tests. New York:

Harper & Row.

Archer, R. P., & Krishnamurthy, R. (1993a). Combining the Rorschach and MMPI in the assessment

of adolescents. Journal of Personality Assessment, 60, 132140.

Archer, R. P., & Krishnamurthy, R. (1993b). A review of MMPI and Rorschach interrelationships

in adult samples. Journal of Personality Assessment, 61, 277293.

Bargh, J. A. (1994). The four horsemen of automaticity: Awareness, intention, efcacy, and control

in social cognition. In R. S. Wyer & T. K. Srull (Eds.), Handbook of social cognition (Vol. 1,

pp. 140). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bargh, J. A., & Morsella, E. (2008). The unconscious mind. Perspectives on Psychological

Science, 3, 7379.

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1993). Beck Depression Inventory manual. San Antonio, TX:

Psychological Corporation.

Beebe, B., & Lachmann, F. M. (2002). Infant research and adult treatment: Co-constructing

interactions. London, United Kingdom: Analytic Press.

Bornstein, R. F. (1993). Implicit perception, implicit memory, and the recovery of unconscious

material in psychotherapy. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 181, 337344.

Bornstein, R. F. (1995). Sex differences in objective and projective dependency tests: A meta-

analytic review. Assessment, 2, 319331.

Bornstein, R. F. (1998). Implicit and self-attributed dependency needs in dependent and histrionic

personality disorders. Journal of Personality Assessment, 71, 114.

Bornstein, R. F. (1999). Source amnesia, misattribution, and the power of unconscious perceptions

and memories. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 16, 155178.

Bornstein, R. F. (2001a). Has psychology become the science of questionnaires? A survey of

research outcome measures at the close of the 20th century. The General Psychologist, 36,

3640.

Bornstein, R. F. (2001b). The impending death of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 18,

320.

Bornstein, R. F. (2002). A process dissociation approach to objective-projective test score interre-

lationships. Journal of Personality Assessment, 78, 4768.

Bornstein, R. F. (2003). Behaviorally referenced experimentation and symptom validation: A

paradigm for 21st century personality disorder research. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17,

118.

Bornstein, R. F. (2005). Reconnecting psychoanalysis to mainstream psychology: Challenges and

opportunities. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 22, 323340.

Bornstein, R. F. (2007a). Might the Rorschach be a projective test after all? Social projection of an

undesired trait alters Rorschach Oral Dependency scores. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88,

354367.

Bornstein, R. F. (2007b). Nomothetic psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 24, 590602.

Bornstein, R. F. (2007c). Toward a process-based framework for classifying personality tests:

Comment on Meyer and Kurtz 2006. Journal of Personality Assessment, 89, 202207.

Bornstein, R. F., Bowers, K. S., & Bonner, S. (1996a). Effects of induced mood states on objective

and projective dependency scores. Journal of Personality Assessment, 67, 342340.

148 BORNSTEIN

Bornstein, R. F., Bowers, K. S., & Bonner, S. (1996b). Relationships of objective and projective

dependency scores to sex role orientation in college student subjects. Journal of Personality

Assessment, 66, 555568.

Bornstein, R. F., & Masling, J. M. (Eds.). (2005). Scoring the Rorschach: Seven validated systems.

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bornstein, R. F., Rossner, S. C., Hill, E. L., & Stepanian, M. L. (1994). Face validity and fakability

of objective and projective measures of dependency. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63,

363386.

Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (1955). Studies in hysteria. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard

edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 2). London: Hogarth.

(Original work published 1896)

Bucci, W. (1997). Psychoanalysis and cognitive science: A multiple code theory. New York:

Guilford Press.

Bucci, W. (2000). The need for a psychoanalytic psychology in the cognitive science eld.

Psychoanalytic Psychology, 17, 203224.

Cadbury, S. (1991). The concept of dependence as developed by Birtchnell: A critique. British

Journal of Medical Psychology, 64, 237251.

Campanella, S., & Belin, P. (2007). Integrating face and voice in person perception. Trends in

Cognitive Sciences, 11, 635643.

Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-

multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56, 81105.

Carr, A. C., & Goldstein, E. G. (1981). Approaches to the diagnosis of borderline conditions by the

use of psychological tests. Journal of Personality Assessment, 45, 563574.

Cattell, J. M. (1890). Mental tests and measurements. Mind, 15, 373381.

Childs, R. A., & Eyde, L. D. (2002). Assessment training in clinical psychology doctoral programs.

Journal of Personality Assessment, 78, 130144.

Coen, S. J. (1992). The misuse of persons: Analyzing pathological dependency. Hillsdale, NJ:

Analytic Press.

Cogswell, A. (2008). Explicitly rejecting an implicit dichotomy: Integrating two approaches to

assessing dependency. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90, 2635.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Craig, J. A., Koestner, R., & Zuroff, D. C. (1994). Implicit and self-attributed intimacy motivation.

Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11, 491507.

Cramer, P. (2000). Defense mechanisms in psychology today: Mechanisms for adaptation. Amer-

ican Psychologist, 55, 637646.

Cramer, P. (2006). Protecting the self: Defense mechanisms in action. New York: Guilford Press.

Epstein, S. (1998). Cognitive-experiential self theory: A dual process personality theory with

implications for diagnosis and psychotherapy. In R. F. Bornstein & J. M. Masling (Eds.),

Empirical perspectives on the psychoanalytic unconscious (pp. 99140). Washington, DC:

American Psychological Association.

Erdelyi, M. H. (1985). Psychoanalysis: Freuds cognitive psychology. New York: Freeman.

Erdelyi, M. H. (2004). Subliminal perception and its cognates: Theory, indeterminacy, and time.

Consciousness and Cognition, 13, 7391.

Erdelyi, M. H. (2006). The unied theory of repression. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29,

499511.

Exner, J. E. (1989). Searching for projection in the Rorschach. Journal of Personality Assess-

ment, 53, 520536.

Exner, J. E. (1991). The Rorschach: A comprehensive system (Vol. 2, 2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Freud, S. (1955). Totem and taboo. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the

complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 3, pp. 159188). London: Hogarth.

(Original work published 1913)

Freud. S. (1953). The interpretation of dreams. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard ed. of

149 PSYCHOANALYSIS AND PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vols. 4 and 5). London: Hogarth. (Original

work published 1900)

Fuerstein, L. A. (1989). Some hypotheses about gender differences in coping with oral dependency

conicts. Psychoanalytic Review, 76, 163184.

Gabbard, G. O. (2000). Psychodynamic psychotherapy in clinical practice (3rd ed.). Washington,

DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Galatzer-Levy, R. M., & Cohler, B. J. (1993). The essential other: A developmental psychology of

the self. New York: Basic Books.

Gallo, D. A., Kensinger, E. A., & Schacter, D. L. (2006). Prefrontal activity and diagnostic

monitoring of memory retrieval: FMRI of the Criterial Recollection Task. Journal of Cognitive

Neuroscience, 18, 135148.

Gilbert, L. A. (1987). Male and female emotional dependency and its implications for the therapist-

client relationship. Professional Psychology, 18, 555561.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of the self in everyday life. Edinburgh, United Kingdom:

University of Edinburgh Social Sciences Research Centre.

Greenberg, J. R., & Mitchell, S. M. (1983). Object relations in psychoanalytic theory. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Groth-Marnat, G. (1999). Current status and future directions of psychological assessment. Journal

of Clinical Psychology, 55, 781785.

Handler, L., & Hilsenroth, M. J. (Eds.). (1998). Teaching and learning personality assessment.

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Handler, L., & Meyer, G. J. (1998). The importance of teaching and learning psychological

assessment. In L. Handler & M. J. Hilsenroth (Eds.), Teaching and learning personality

assessment (pp. 330). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hartmann, H. (1964). Essays on ego psychology. New York: International Universities Press.

Higgins, E. T., & King, G. A. (1981). Accessibility of social constructs: Information-processing

consequences of individual and contextual variability. In N. Cantor & J. F. Kihlstrom (Eds.),

Personality, cognition, and social interaction (pp. 69122). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Higgins, E. T., & Pittman, T. S. (2008). Motives of the human animal: Comprehending, managing,

and sharing inner states. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 361385.

Hirschfeld, R. M. A., Klerman, G. L., Gough, H. G., Barrett, J., Korchin, S. J., & Chodoff, P. (1977).

A measure of interpersonal dependency. Journal of Personality Assessment, 41, 610618.

Holt, R. R. (1966). Measuring libidinal and aggressive motives and their controls by means of the

Rorschach test. In D. Levine (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (pp. 147). Lincoln:

University of Nebraska Press.

Huprich, S. K. (2009). Psychodynamic therapy: Conceptual and empirical foundations. New York:

Taylor & Francis.

Jacoby, L. L., & Kelley, C. M. (1991). Unconscious inuences of memory: Dissociations and

automaticity. In D. Milner & M. Rugg (Eds.), The neuropsychology of consciousness (pp.

201233). London, United Kingdom: Academic Press.

Kammrath, L. K., Mendoza-Denton, R., & Mischel, W. (2005). Incorporating if-then personality

signatures into person perception: Beyond the person-situation dichotomy. Journal of Person-

ality and Social Psychology, 88, 605618.

Klopfer, W. G. (1960). The psychological report: Use and communication of psychological ndings.

Oxford, United Kingdom: Grune & Stratton.

Koestner, R., Weinberger, J., & McClelland, D. C. (1991). Task-intrinsic and social-extrinsic

sources of arousal for motives assessed in fantasy and self-report. Journal of Personality, 59,

5782.

Kohut, H. (1971). The analysis of the self. New York: International Universities Press.

Laplanche, J., & Pontalis, J. B. (1974). The language of psycho-analysis. New York: Norton.

Lerner, H. E. (1983). Female dependency in context: Some theoretical and technical considerations.

American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 53, 697705.

Lerner, P. M. (2005). Defense and its assessment: The Lerner Defense Scale. In R. F. Bornstein &

150 BORNSTEIN

J. M. Masling (Eds.), Scoring the Rorschach: Seven validated systems (pp. 237269). Mahwah,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Luborsky, L., & Crits-Christoph, P. (1990). Understanding transference: The Core Conictual

Relational Theme method. New York: Basic Books.

Maner, J. K., Kendrick, D. T., Becker, D. V., Robertson, T. E., Hofer, B., Neuberg, S. L., et al.

(2005). Functional projection: How fundamental social motives can bias interpersonal percep-

tion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 6378.

Masling, J. M. (1990). Preface. In J. M. Masling (Ed.), Empirical studies of psychoanalytic theories

(Vol. 3, pp. vxv). Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

Mayman, M. (1959). Style, focus, language, and content of an ideal psychological test report.

Journal of Projective Techniques, 23, 453458.

McClelland, D. C., Koestner, R., & Weinberger, J. (1989). How do self-attributed and implicit

motives differ? Psychological Review, 96, 690702.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American

Psychologist, 52, 509516.

Messick, S. (1995). Validity of psychological assessment: Validation of inferences from persons

responses and performances as scientic inquiry into score meaning. American Psychologist, 50,

741749.

Meyer, G. J. (1996). The Rorschach and MMPI: Toward a more scientic understanding of

cross-method assessment. Journal of Personality Assessment, 67, 558578.

Meyer, G. J. (1997). On the integration of personality assessment methods: The Rorschach and

MMPI. Journal of Personality Assessment, 68, 297330.

Meyer, G. J., Finn, S. E., Eyde, L. D., Kay, G. G., Moreland, K. L., Dies, R. R., et al. (2001).

Psychological testing and psychological assessment: A review of evidence and issues. American

Psychologist, 56, 128165.

Meyer, G. J., & Kurtz, J. E. (2006). Advancing personality assessment terminology: Time to retire

objective and projective as personality test descriptors. Journal of Personality Assess-

ment, 87, 223225.

Morey, L. C. (2003). Essentials of PAI assessment. New York: Wiley.

Murstein, B. I. (1956). The projection of hostility on the Rorschach as a result of ego-threat. Journal

of Projective Techniques, 20, 418428.

Murstein, B. I., & Wolf, S. R. (1970). Empirical test of the levels hypothesis with ve projective

techniques. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 75, 3844.

Newman, L. S., Duff, K. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (1997). A new look at defensive projection:

Thought suppression, accessibility, and biased person perception. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 72, 9801001.

Piotrowski, C., & Belter, R. W. (1999). Internship training in psychological assessment: Has

managed care had an impact? Assessment, 6, 381389.

Porcelli, P., & Meyer, G. J. (2002). Construct validity of Rorschach variables for alexithymia.

Psychosomatics, 43, 360369.

Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., & Solomon, S. (2000). Proximal and distal defense: A new

perspective on unconscious motivation. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9, 156

160.

Rapaport, D., Gill, M. M., & Schafer, R. (1945). Diagnostic psychological testing. Chicago:

Yearbook Publishers.

Rapaport, D., Gill, M. M., & Schafer, R. (1968). Diagnostic psychological testing (rev. ed.). New

York: International Universities Press.

Russ, S. W. (1996). Psychoanalytic theory and creativity: Cognition and affect revisited. In R. F.

Bornstein & J. M. Masling (Eds.), Psychoanalytic perspectives on developmental psychology

(pp. 69103). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Schacter, D. L. (1987). Implicit memory: History and current status. Journal of Experimental

Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 13, 501518.

151 PSYCHOANALYSIS AND PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

Schafer, R. (1954). Psychoanalytic interpretation in Rorschach testing. New York: Grune &

Stratton.

Schimel, J., Greenberg, J., & Martens, A. (2003). Evidence that projection of a feared trait can serve

a defensive function. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 969979.

Silverstein, M. L. (2007). Disorders of the self: A personality guided approach. Washington, DC:

American Psychological Association.

Sperling, M. B., Sack, A., & Field, C. L. (2000). Psychodynamic practice in a managed care

environment. New York: Guilford Press.

Stedman, J. M., Hatch, J. P., & Schoenfeld, L. S. (2001). Internship directors valuation of

pre-internship preparation in test-based assessment and psychotherapy. Professional Psychology:

Research and Practice, 32, 421424.

Stern, D. (2004). The present moment in psychotherapy and everyday life. New York: Norton.

Sugarman, A. (1991). Wheres the beef? Putting personality back into personality assessment.

Journal of Personality Assessment, 56, 130144.

Sugarman, A. (1992). A psychoanalytic approach to the inference process in diagnostic testing.

British Journal of Projective Psychology, 37, 3449.

Sugarman, A., & Kanner, K. (2000). The contribution of psychoanalytic theory to psychological

testing. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 17, 323.

Wachtel, P. L. (1977). Psychoanalysis and behavior therapy: Toward an integration. NY: Basic

Books.

Wachtel, P. L. (1997). Psychoanalysis, behavior therapy, and the relational world. Washington,

DC: American Psychological Association.

Wegner, D. M., & Erber, R. (1992). The hyperaccessibility of suppressed thoughts. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 903912.

Weinberger, J., & McClelland, D. C. (1990). Cognitive versus traditional motivational models:

Irreconcilable or complementary? In R. Sorrentino & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of

motivation and cognition (pp. 562597). New York: Academic Press.

Weiner, I. B. (2004). Rorschach Inkblot Method. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological

testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (3rd ed., pp. 553588). Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Weiner, I. B., & Bornstein, R. F. (2009). Principles of psychotherapy (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Westen, D. (1998). The scientic legacy of Sigmund Freud: Toward a psychodynamically informed

psychological science. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 333371.

152 BORNSTEIN

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Jenniferrollinresume 2017 RevDocument2 paginiJenniferrollinresume 2017 Revapi-296912905Încă nu există evaluări

- Research Proposal For GE2 2.docx2Document18 paginiResearch Proposal For GE2 2.docx2Robelyn Salvaleon BalwitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Online Rorschach Inkblot TestDocument12 paginiOnline Rorschach Inkblot TestSubhan Ullah100% (1)

- High School Research Paper InfoDocument3 paginiHigh School Research Paper InfoMerzi Badoy100% (1)

- MSC Mental Health: School of Health SciencesDocument9 paginiMSC Mental Health: School of Health SciencesRawoo KowshikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rotter's Incomplete Sentence Blank TestDocument9 paginiRotter's Incomplete Sentence Blank Testrahat munirÎncă nu există evaluări

- 14Document6 pagini14marissa100% (1)

- Chapter 9: IntelligenceDocument34 paginiChapter 9: IntelligenceDemiGodShuvoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rorschach Ink-Blot Test: Niharika ThakkarDocument24 paginiRorschach Ink-Blot Test: Niharika ThakkarAdela Mechenie100% (1)

- Projective Personality TestsDocument16 paginiProjective Personality TestsVibhasri GurjalÎncă nu există evaluări

- 16PF BibDocument10 pagini16PF BibdocagunsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychological Testing AssessmenttDocument30 paginiPsychological Testing Assessmenttjaved alamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture15 PsychophysicsDocument22 paginiLecture15 PsychophysicstejaldhullaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DAPT SCT HandoutDocument5 paginiDAPT SCT HandoutUdita PantÎncă nu există evaluări

- SOC301 - Short and Highlighted - Notes by Pin and MuhammadDocument125 paginiSOC301 - Short and Highlighted - Notes by Pin and MuhammadMohammadihsan NoorÎncă nu există evaluări

- The MMSEDocument4 paginiThe MMSESiti Zubaidah HussinÎncă nu există evaluări

- STAT Statistical Inference: Lecture# 18Document10 paginiSTAT Statistical Inference: Lecture# 18Saad Nadeem 090Încă nu există evaluări

- History and Evolution of DSMDocument5 paginiHistory and Evolution of DSMTiffany SyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Programme Standards: Psychology: Malaysian Qualifications AgencyDocument52 paginiProgramme Standards: Psychology: Malaysian Qualifications AgencyBella RamliÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2013 Ethical IssuesDocument27 pagini2013 Ethical Issuesclarisse jaramillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychological Assessment ReportDocument3 paginiPsychological Assessment ReportmobeenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics in PsychologyDocument6 paginiEthics in PsychologySafa QasimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moral Development: Chapter 11 - Developmental PsychologyDocument16 paginiMoral Development: Chapter 11 - Developmental PsychologyJan Dela RosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thematic Apperception Test TutorialDocument26 paginiThematic Apperception Test TutorialRaunak kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- TAT (Thematic Apperception Test)Document36 paginiTAT (Thematic Apperception Test)ChannambikaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Examination in Projective Techniques: Submitted To: Connie C. Magsino ProfessorDocument7 paginiFinal Examination in Projective Techniques: Submitted To: Connie C. Magsino ProfessorIan Jireh AquinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women Offender in Criminal Justice System: A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument21 paginiWomen Offender in Criminal Justice System: A Systematic Literature ReviewJoseMelarte GoocoJr.Încă nu există evaluări

- Majorly Covers PsychometricDocument214 paginiMajorly Covers PsychometricAkshita SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case History FormatDocument7 paginiCase History FormatSaranya R VÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Learning A First Language NewDocument42 pagini1 Learning A First Language NewlittlefbitchÎncă nu există evaluări

- Response Set (Psychological Perspective)Document15 paginiResponse Set (Psychological Perspective)MacxieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social-Desirability Sacle PDFDocument2 paginiSocial-Desirability Sacle PDFtwinkle_shahÎncă nu există evaluări

- EIS HPD FinalDocument11 paginiEIS HPD FinalJhilmil GroverÎncă nu există evaluări