Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Flynt Henry On Pandit Pran Nath

Încărcat de

analogues0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

26 vizualizări20 paginiIn the early Seventies, Guruji's usual vocal tone was round, completely unforced in the lower range. In a master class at Harrison st., he sang a capella, then brought the tamburas in and they were on the SA he was on. Guruji had absolute pitch -- in a raga, he hides the tone to be introduced in the melodic shape at first use.

Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Flynt Henry on Pandit Pran Nath

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentIn the early Seventies, Guruji's usual vocal tone was round, completely unforced in the lower range. In a master class at Harrison st., he sang a capella, then brought the tamburas in and they were on the SA he was on. Guruji had absolute pitch -- in a raga, he hides the tone to be introduced in the melodic shape at first use.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

26 vizualizări20 paginiFlynt Henry On Pandit Pran Nath

Încărcat de

analoguesIn the early Seventies, Guruji's usual vocal tone was round, completely unforced in the lower range. In a master class at Harrison st., he sang a capella, then brought the tamburas in and they were on the SA he was on. Guruji had absolute pitch -- in a raga, he hides the tone to be introduced in the melodic shape at first use.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 20

On Pandit Pran Nath (1918-1996)

Henry A. Flynt, Jr.

December 1996 March 2002

There is a short glossary at the end of the first section. Names of scale

tones are in caps. Western note names assume C as the tonic, e.g. C D

E F G A B c. Appreciation is due La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela

for overseeing the musical knowledge here (not to mention sponsoring

Guruji in New York).

When the ragas are starred, specific recordings are referred to. There

is a discography after the glossary.

In the early Seventies, Gurujis usual vocal tone was round, completely

unforced in the lower range (only occasionally raspy); only occasionally

cutting as he rose to high SA. His intonation, vocal quality were beyond

compare.

He would pour the raga out like a physically massive storyteller; his

production was speech-like, not colorlessly pure. It was always earthy,

not preciousa certain roughness of speech.

Visceral qualities of the music had an effect. Gurujis occasional

dwelling on tones in the low octave, as in Malkauns. A visceral sense of

grounding or foundation.

Guruji told Young, you cant learn my style from records, you cant learn

it unless I teach it to you. The technique and thought of his

performancessome recollections.

1. the unforced vocal production in the low range comes from

developing the voice at full strength and then easing off.

2. Guruji had absolute pitch in a master class at Harrison St., he

sang a capella, then brought the tamburas in, and they were on

the SA he was on.

3. in a descending melodic shape, a descending mind, accenting the

beginning of a descending slide a technique especially used in

Kirana *Darbari alap

4. exposition of the raga: the pitches are successively involved in the

melodic shapes in ascending order Guruji hides the tone to be

introduced in the melodic shape at first use, so that the audience

has heard it before they are aware of its use discrete change

across the perceptual threshhold

5. in Hindustani music, the first note is supposed to prefigure the

entire performance, which unfolds from it in our terms, the way

SA is produced and ornamented.

6. resting on a scale tone, usually in the lower octave, SHUDDH NI

below SA, shaping melody as if to tonicize NI, then revealing the

tonal center as SA (*Yaman, *Todi)

7. ascending as expected to PA, but passing right through it to

KOMAL DHA the surprise

8. the yodel-like upward break at the end of an intense sustained

high tone, SA gitkiri

9. the use of the lower octave, gliding like a rudra vina and dropping

to kuraj, conveying a visceral sense of being completed or

grounded Malkauns

10. I heard him run the descending scale as if it were being strummed

on sympathetic strings Harrison Street, Multani, 1980?

11. a late morning performance at Harrsion St. Guruji sang a drone

(tambura) pitch, SA or PA, in a way that gave the impression of

resonance like a sarangi, a shimmer a microtonal andolan? I

associated the sight of silver with it (around 1980)

12. in live performance, an ascending mind would make you feel like

it was lifting your virtual torso from where you were sitting. two

examples from *Darbari: in the lower octave, his ascending mind

in ahkar from MA to SA in the middle octave, his ascending

mind from PA to upper SA

13. In the drut he would demonstrate just enough tricky syncopation

to show that he could do it.

*Bhairava 19 V 1974

Guruji draws entirely different moods as he brings MA, PA, DHA, NI

into the melodic shapes. He conjures up

joy

pensiveness, sublimated moroseness

a zingy flavor

When he introduces NI, the theme descends to GA or RE the zingy

flavor of Ab, F, E, F, Ab, B, c, B, Ab, F (C/G drone).

[the flavor reminds me of Ram Narayans descending theme in the gat,

*Todi, from SA to RE although the intervals are quite different]

Singing on the pentachord from PA to SA: GA, MA, PA, lullaby-like,

vulnerable, intimate joy [Indian writers say tender adoration the

shape not typical because DHA is the vadi of Bhairava] then descend

to SA through KOMAL RE, the touch of the exotic or macabre. Near the

end of the performance.

Hindustani music, an inexplicable inspiration. The carefully thought-

out techniques to make the music intimate, uncanny, cosmic.

(Resonance and scale choices.) Conjuring up joy, offering the vicarious

experience of [or vicarious return to] grief, a pensive emotional flavor, a

zingy emotional flavor.

To experience the emotions of an occurrence at one remove from it.

Vicarious

To aestheticize the emotion, detach it from the jolting occasion.

Sublimated

The whole question of artistic use of the eerie, uncanny, sombre,

morose, morbid, macabre which is central in Hindu mythology. It is

involving, not estranging, if it is sublimated [done with acceptance]

excluding resentment and ridicule.

Why does the vicarious encounter of grief conjured up with tones have a

healing, remedying effect? [this function is intended in traditional

music, characteristically]

Our emotion makes us real, and deep, and we want to re-experience it as

a re-commitment to our depth. (And as a way of mastering or absorbing

a loss or injury.)

The evoked joy is elicited, is real, not aestheticized.

A joy that heals despair and grief.

In *Asavari, Gurujis performance is profoundly mastered in terms of

system and technique. Yet he stays close to the intonation of speech,

chant, the storyteller. An ancient sound. He never turns himself into a

musical instrument. He never leaves the intonation of speech, chant,

storytelling.

His ahkar tans are usually offhand. But he drives it in the drut of *Todi.

Its about developing the feelings, so that there is a reserve in other

aspects. He shows the boogie beat or groove and then drops it. He

doesnt want getting in a groove, propulsion by instinct, to be what it is

about. His intelligence is always on.

Guruji had many strategies of melodic exposition which made his sound

subtle and uncanny. But what really mattered was beyond the definable

techniques.

Glossary [bracketed is pronunciation]

gharana family, style, school

drupad chanted performance

khayal imagination, improvisation which develops the raga

Purabanga [purvanga] lower tetrachord

Uttaranga [utterang] upper tetrachord

kuraj [courage] any SA; lowest SA; lowest octave

Mandhra [mandra] lower octave

Madhya middle octave

Tar upper octave

lay tempo

arohe [aro] ascending scale

avrohe [avro] descending scale

vadi melodically dominant scale tone

samvadi melodically supporting scale tone

Sargam solfeggio

asthayi [astay] first verse of song, lower tetrachord

antara [antra] second verse, introduce upper tetrachord, and express

the inner feeling of the raga

alap first section of performance

unmeasured beginning of alap nom tom style (drupad); avahan style

(khayal, sung in ahkar)

slow measured alap vilampit

madhyalay [madyalay] later section, measured medium tempo

drut last section, rapid

gat in instrumental music, measured later section

ahkar melisma on ah

mind [meend] sliding

lehak [layhok] winding

andolan swinging between tones

gitkiri voice break

tan a pitch sequence in tempo, or run

sargam tans tans on sargams

ahkar tans tans on ah

bol tans tans on tabla mnemonics

unpublished

19 V 74 NYC

Pandit Pran Nath

Raga Bhairava

K. Paramjyoti - tabla

discography

Earth Groove (Bhupali, Asavari) Douglas SD784 (1968)

Pandit Pran Nath (Yaman Kalyan, Punjabi Burva) Shandar 10007

(1972)

Ragas of Morning and Night (Todi, Darbari) Gramavision 18-7018-7

(1986)

Masters of Lahore and Bengal from the 1930s and 1940s [label

unknown]

inde du nord (Ram NarayanShuddh Todi, Marva) disques BAM LD

094

I was beside myself for days after hearing *Bhairava 19 V 1974.

Once one has been seized up

Without a part left over,

Not a toe, not a finger, and used,

Used utterly, in the suns conflagrations

What is the remedy?

Sylvia Plath

The sense that there was this supremely intelligent strategy in back of

his invocation of your appreciation of poignancy and exaltation.

For his students, who were career musicians, the question was how was

it musically possible. My question is, how was it humanly possible?

Pandit Pran Nath was more fully realized than blues musiciansno less

honor to thembut he had an advantage of context. He did not have to

practice an illicit music while situated socially below a hostile

majority. (Although his parents threw him out at 13 for wanting to be a

musician.) He was at home, in his own country, his own tradition, and

the musical vocation entailed a comprehensive yogic discipline which

is not expected in the West. The European modernist project of

annuling tradition was not an issue in his landscape.

All the same, he departed the expected Hindustani practice to the point

where he was alone (and not universally beloved) in his originality.

Guruji went to strange emotional places, already familiar in his native

culture, which the West would call surrealistic or like an inexplicable

dream. But instead of being odd in an estranging way, it involved you;

he forcibly confronted you with your own appreciation of emotion,

poignancy, and exaltation. It took you into yourself and showed you

that you have sensibilities, and nobility, you did not know about.

A sensibility of poignancy and exaltation. Other Hindustani singers are

great entertainers. Gurujis job description was: to awaken your true

self. The most remarkable thing is that he chose the path of probing

people emotionally, reaching them in an earthy and basic way and yet

with an underlying strategy of the highest intelligence. He channeled

his incredible technique into emotional confrontation, into involving us

emotionally.

Why did Guruji want to elicit our humanity? Where did Gurujis

capacity to elicit [awaken, vivify] our humanity come from?

It brings us up against the word humanity. The usage is colloquial. A

biological metaphor for the dignity of the person, the object of the

greatest phobia and hatred in the West. (Even as the Wests jeering

cultural leaders demand that they and theirs be treated with the utmost

graciousness.) This discussion will not be grounded until humanity has

been semantically validated, or replaced with literal language.

The realm of the performance honors real emotion, honors self-respect.

When a communication conveys this, it is awesome to the receptive

listener. We are inherently oriented so that a realm of self-respect

and emotional honesty, a realm without self-masking, evokes awe. A

more valid/real sensibility/consciousness. How do the meanings of

valid and real relate in this context? The truth/reality of ones self

and of ones proper future. When another person conveys this to me

dissolves my pretense with myselfI experience that person as having

the advantage of me.

Was it Pandit Pran Naths achievement precisely to take people into

themselves and show them that they had sensibilities and heights which

were latent, which they did not suspect? The music lets you regain,

revivifies, a feeling which you lost access to. Hence it is predicated on

his continuity with other people. Hence it imagines that there would be

a way of life that honors real emotion, that is self-respecting.

I was sitting in the Tishman Auditorium at the New School (fall 1970)

before Guruji walked on stage. A young man was sitting next to me

and I had a copy of the latest Monthly Review (Stalinism for Fabians)

and may have been browsing it. We fell into a conversation, finding

that we both sympathized with the publication, and he cut it short by

saying its impossible to think about that here.

But if most people ideally should be serfs and philistines, what is the

musics promise? Let there be an aristocracy of people who find

themselves: even these people are not aloof from society all the time,

and have to be recalled to themselves. And surely there are people who

are prevented from doing what they should by mundane burdens. To

separate inspiration and social engineering is to condemn people to

never have anything but isolated glimpses of the best of themselves.

This is America, and people dont take thirty or forty years of unpaid

leave to pursue matters of principle. And yet, as I try to tell my

associates, you cant understand a matter of principle by browsing it

like a Sunday supplement article. You have to be engrossed in it, to

work for hundreds of hours on it.

To be in Gurujis audience was to encounter that which has the

advantage of you. Inspiration beyond anything you ever expected to

know in your life. An encounter with something that solves a problem

for you, that you would not have scripted. It opens a door intellectually,

vivifies the life-tone. Being in the presence of such inspiration and

dedication is humbling. I had a take that I must be near the end of my

life since I am encountering a greater reality, something there is no

precedent for in everyday life. Since I am blessed with something so

much finer than the usual, something so far from the present public

norm.

What is it worth to be instructed in feeling, to be opened up emotionally

in a sensitive, conducive way?

What is it worth to be taken into yourself and shown that you had

sensibilities and heights which were latent, which you did not suspect?

What is it worth to renew your acquaintance with joy?

What is it worth to be confronted with the degree to which you are

short-changed by the world around you (and by yourself)?

How many people have a power, to heal despair (or grief), which goes

beyond personal complementation, being the soulmate of one other

person? Or have a power to show where the truth/reality of ones self

and proper future is?

Guruji challenged anyone, but probably the Westerner the most: you

have short-changed yourself, the milieu has cheated you. The moment

of regret or remorse for all the times you cheated yourself. The far

greater consideration, how your native civilization cheated you.

Libby Flynt says that Indians think in terms of a perennial dichotomy

between profane mundane life, and a person who refines self. Indians

see a perpetual dichotomy between the profaneness of the mundane

world and the inspiration and refinement of their music. The Pandit in

India needs intoxication to be able to bear the mundane worldis happy

only when singing.

The individual in question has a personal intent and absorbs from elders

and cohorts and is trained by mentors. There comes a point when the

mentors mission no longer prevails; the students intent takes over.

The former student may continue to absorb from cohorts, now

harnessing to a distinctive intent that which is absorbed. Acquisition

from others may continuethe role of learning from others varies from

case to casebut a new, distinctive intent prevails. The surfacing of the

qualitatively new. (The reason we are talking about the intent or

mission is not that it is neutrally or abstractly new but that it is

valuable in the respects I have outlined above.) One may always be

acquiring and harnessing ideas from others. Even so, everything is

reorganized to serve a new intent, a new mission.

It starts with demanding what is noble from oneself. Not just the

mechanical talent, the fast fingers. The aspiration to bring people to

ennobling (or just deeper) feelings, feelings perhaps unknown to them.

Even as Gurujis achievement was predicated on his continuity with

other people, there was also a discontinuity. Other people would not

have chosen, or found, his path of nobility, nor could they have. Here

was a summit of achievement as a musical performer unreachable for

anyone else.

The new, distinctive intent emerges somewhat subtly, since it emerges

while the individual is being familiarized and taught, since it only gains

mastery after an apprenticeship. Nevertheless, it comes to outrank the

precedents and to transform what it, and the precedents, mean for us. A

qualitative novelty confronts us which has the advantage of us. It is

unsatisfying to explain it as the product of social influences, because it

goes precisely where those social influences did not go. It does what

nobody asked for.

During his apprenticeship, Pandit Pran Nath obviously absorbed

content from others, his mentors and cohorts. (i) Does there come a

point where his content comes entirely from him? (ii) Does he receive

energy from a (non-social) outside after he establishes himself as an

original?

The normative outlook in this civilizationthat is, naturalism-

secularismmust answer (i) yes, (ii) no. The normative outlook has it

that Gurujis artistic capabilities were entirely within him. They were

extinguished when he expired.

The normative outlook, I must say, becomes a difficulty to itself. If we

speak of cultures, they are a matter of the transmission of meaning. But

the normative outlook has no more of an ontological analytic of the

transmission of meaning than it does of the subjectivity of the subject.

Transmission of meaning is a transpersonal subjectivity, and as such,

the normative outlook does not and cannot acknowledge it. The only

way it understands communication is as in information theory, as the

physics of the notation-token.

For all that, Indian music is a collective achievement and an honorable

one in the sense that any proficient performer will be worth hearing.

But even if the normative outlook allowed us to invoke cultures as

explanations, it would not explain Guruji. At some point, Pandit Pran

Nath outstripped his cultural influences. He projected a distinctive

intent which could not be explained by cultural influences.

Where do anyones personalistic subjectivities come from? (The

audiences receptivity, for example.) Not from being. (Not from

what-is labelled as a person or thing, the way we label nothing.)

Might my personalistic subjectivities derive from what-is as part of a

whole which I did nothing to earn, like my equilibrium with sunlight

and air? If the normative outlook is the context, its a misleading

question. For the normative outlook, what-is is the totality of things,

like Thales water or Archimedes universe packed with sand.

Personalistic subjectivities are heterogeneous with sunlight and air. If

what-is is supposed to encompass heterogeneities in this sense, then we

are outside the normative outlook without an explanation of how we left

it.

The normative outlook cannot address personalistic subjectivities as

such. (Cf. Marvin Minskys The Society of Mind. The normative outlook

rebuffs personalistic subjectivities with slashing contempt. Again the

normative outlook is a difficulty to itself.) But the normative outlooks

informal verdict must be that personalistic subjectivities subsist where

they manifestinside the individual. My subjectivities may be molded

from without, but they do not live outside me. (Except in my works and

in particular my communicative works? That doesnt get us anywhere,

since the normative outlook rebuffs the transmission of meaning with

slashing contempt.)

The normative outlook accumulates difficulties for itself. The gift is

inside the gifted individual. Then that individual has an unfathomable

advantage of the rest of us. If it all came from inside Guruji, he must be

of a different order from the rest of us. Then aristocray is a fixture of

our collective existence. (The only reservation is that this aristocracy

does not always enjoy success. See below.)

What about the socio-psychological axiom that says, nobody is an

aristocrat by nature? Or the weaker axiom that says, if there are

aristocrats by nature, they are randomly distributed? Does democracy

require the former axiom? Does it require the latteremphatically yes.

If there is a systematic natural aristocracy, then democracy is at best

an expedient lie, a scheme to co-opt restive masses.

All humans may be vaguely similar, but in detail, all are not the same.

Some people display an incontestable, unfathomable advantage over

othersalthough perhaps in a different dimension in every case of such

an advantage. The normative outlook doesnt know what to do with

incontestable advantages and their rebuke to democracy.

Again we speak of Pandit Pran Nath as a graduated apprentice, age 31.

Does his unique intent come from a non-social outside? The

normative perspective must give the question a vehemently

negative answer. After all, if such an outside were

straightforwardly evident, then the modern world-picture

would have accounted for it in the course of the days work.

Philosophers would be able to tell us the reality-type of this

outside without further ado, without departing from their

standard themes. The point is that there is no official

exposition of the demanded non-social outside from

proximate evidence.

The notion of the outside comes to us from exponents of religions.

Religions rest on beliefs from ancient timeswhen peoples picture of

the cosmos was necessarily different from what it is now. A god: a man

who sits on a chair in the sky and happens to be immortal and

incorporeal. (Who was given a promotion to infinity by the Latin

Averroists, one jump ahead of the Inquisition.) A god: a unique

monarch of the universe whose egoic impulses define goodness.

Ancient peoples, being more helpless in the world than we are, being

unable to accommodate sophisticated social legitimation, submitted to

their pictorial fantasies. Five major religions arose, Islam being the last,

and then the creation of major religions stopped. People wont listen to

spiritual speculation from sources other than these religions, because

the legitimation of state actions rests on the authority of familiarity.

Political legitimation rests on locked-in ideologies. The god-picture of

religion was never a rational speculation. It was always wishful

thinking.

I shall not pretend that the earth is flat and the center of the universe

and that a man with a beard could sit on a chair in the sky forever and

all the rest of it. To be more blunt, it is with atomic bombs that the

holy nations of India and Pakistan menace each other. I require that

we encounter modernity at its eye-level, not below it, and draw on

evidence, not legend. For me, it is not acceptable to switch from physics

to Hinduism and back to physics as the occasion dictates. That is

equivalent to turning quaintness on and off like a light switch.

All the while, there is a profound lesson on the sidelines of this

discussion. The life-world is filled with commmonplaces, like

personalistic subjectivities, like choice-making, like the transmission of

meaning, which the normative outlook rebuffs with slashing contempt.

As we said, the normative outlook becomes a difficulty to itself. We

propose to open doors. The normative outlook closes them. We have to

give the life-world its due: for my reflections on Pandit Pran Nath to be

compelling.

What did I say above? If such an outside were straightforwardly

evident, then the modern world-picture would have accounted for it in

the course of the days work. Philosophers would be able to tell us the

reality-type of this outside without further ado, without departing from

their standard themes. I retract that. The normative outlook

viciously rebuffs lived experience. Nothing is nearer to me than the

escape routeand yet modern Western civilization extirpates it with

hysterical frenzy.

As a rhetorical device, I am pretending to be more baffled than I am. I

am addressing religious notions and scientific notions argumentatively

because they are implanted in the respective social circles in which

Guruji moved and to which his public belongs.

The normative outlook becomes a difficulty to itself in another way.

Rejection of a non-social outside implies that the judge of ones

solitary endeavors is inside oneself. It is all about ones counsel with

oneself. But then we trip over the normative outlooks commitment to

mundane sociality. If the person judging me is merely myself, the

normative outlook appraises the judge to be reclusive, schizoid, trivial

and transitory.

What the normative outlook answers negatively would have been

answered affirmatively by Pandit Pran Nath. My deliberately vague

formulations might have annoyed him, because he had no reservations

about being antique intellectually as well as musically. He said that

one sings for God. He said that he could not have performed

as he did without the blessings of the saints. Because Pran

Naths circle puts traditional notions of a God and saints into play, I

have to reply in ways which I would say are concessionary in other

contexts.

Pran Nath could believe what he did because he never set himself the

task of confronting modern science. (And because his native culture did

not drive him to the brend critiquesee the note at the end.)

Pran Nath thought his music worshipped God. Very well, J. S. Bach

would have said the same thing. And so would Hindemith. Pran Nath

believed that music possessed an absolute truth. Then J. S. Bachs

music would be an absolute truth.

The catch is that I have no respect for J. S. Bach. Or for Hindemith. At

best, common-practice music constitutes a poisoned experiment.

Common-practice music was Pran Naths mortal enemyif he had only

known what I know about musicology! Pran Nath only had to learn

good things. Im from the West, and from an avant-garde center; I had

to learn European serious music and modernism.

One doesnt create for God. It is preposterous that an infinite god

would be concerned with human pastimes such as music. The notion

that human ears would matter to the infinite god (why not a dogs ears?)

is preposterous. And how would this infinite god sort out Pran Nath and

Bach? Pran Naths music was intersubjectively significant because it

awakened dignity among those whose emotional faculties were

human. (It sublimated that which was human). To have wider

significance, Pran Naths music needs a palpable audience, not a divine

audience.

Why did Pandit Pran Nath have the advantage of us? Perhaps someone

will say, because the god favored him. But does that explain anything?

Presumably Pandit Pran Nath rubbed shoulders with many people who

wanted the gods blessings. Why did the blessings go to Pandit Pran

Nath? He exhibited not so much the mandate of a religion which

everyone shared, as a personal willfulness which remained

controversial.

I admire anyone who is as unusual as Pandit Pran Nath was and

manages to avoid a tragic life. Pandit Pran Nath was comfortable,

lionized, known around the world. But it wasnt all glory, not by a long

shot. To date, he has three records. He is known only to a thin layer of

the cognoscenti. And he was overtaken by severe illnesses, beginning

with the heart attack of 1978, so that he could not give the best account

of himself in the last phase of his career.

If the path of nobility carries penalties, the explanation that the god

mandated those penalties for Pandit Pran Nath is not satisfying. If what

he did was good, why does the god arrange it so that it remains

obscure? What good purpose did Pandit Pran Naths decline serve?

I dont want to be this concessionary. Why does the outside have to be

a man on a chair in the sky who is immortal and unique? (Recall that

Pran Nath was a polytheist.) Astrophysics: our universe is probably an

experiment by a committee of extra-terrestrial scientists. Why cant the

controllers be a committee of extra-terrestrial scientists? As somebody

said, at least the committee of extra-terrestrial scientists could become a

testable hypothesis. The infinite man on the chair in the sky is

scientifically worthless. But as long as there is not a shred of positive

evidence for any of it, none of these speculations are worthy of being

argued here. (I leave the debate over the extra-terrestrial scientists to

the astrophysics journals.)

The myth for children is that everyone succeeds precisely in proportion

to his or her submitted contribution. In fact, when an applauded public

figure lives in good faith and genuinely contributes, I consider that

extremely atypical. If a person is famous and actually has something to

say, it is extremely atypical. Pandit Pran Nath, above all, exemplified

that it can happen.

Part of Pran Naths specialness was that he was a naga in a cave temple

from age 26 to age 31, singing for God. In the West, successful people

campaign for success their entire working lives; they dont have long

episodes of refusing success. In 1949, Pran Naths guru Abdul Wahid

Khan instructed him to go back into the world, and he did. His

contribution wouldnt have been the same without the public

dimension. It wouldnt have been a participatory occasion, a

celebration. His native culture didnt think in terms of making home

recordings and storing them for decades. Its a little like being a dancer;

you cant write a dance and put it in the drawer for posterity. If a dancer

is not seen live, then the dance was not realized. Success (limited as it

was) was a constituent of Pran Naths contribution.

Hindustani music is an honorable community. So is rhythm and blues.

Any proficient performer will be worth hearing. But it may happen that

the master resides in a milieu in which crowd-pleasers and hustlers

predominate numerically. Another regrettable neighbor is inflicted on

the master by modern art, namely the hollow intimidator. But Pandit

Pran Nath lived in the midst of a disaster in New York which is of a

different orderalthough he never seemed to be aware of it, being

sheltered by his hosts as he was. A culture which derides dignitya

contest to see who can be the most sordid and degraded. Up the street,

the Ramones were singing beat the brat with a baseball bat.

From my vantage-point, the person who has something to say and is

also a success is a thoroughly baffling manifestation. All the more so if

that person can be impervious to the chorus of derision, the immersion

in the sordid, which came after flower power in New York.

Pandit Pran Nath could disregard punk as long as his sponsors were

able to assemble audiences for him. If there were those who viewed

Pandit Pran Nath and punk as interchangeable entertainments of an

evening, that is troublingbut Guruji could remain unaware of it.

If enlightenment is utterly discontinuous with everyday life, then

presumably everyday life crushes people. Guruji did not address this

problem: outside of professional musicianship and the reminder which

a performance furnishes to the passive audience.

As for the masters known to us, how do they manage the conjunction of

greatness and success? How can a master be cheerfully impervious to

the milieu? They pour themselves into specialization. They play to an

identified role. The role is already there, and they step into it. They

offer themselves to the public in a single dimension. In fact, the

combination of accomplishment in one dimension with worldly status is

what is meant by being an adult. All the while, these figures block out

most of the challenges implicit in the culture.

The myth for children is that everyone succeeds precisely in proportion

to his or her worth, but as I said, it is thoroughly baffling to me when

anyone who has something to say gains success. I want to speak about

how matters appear from my vantage-point. It is outside my personal

experience to be rewarded commensurately for doing something worth

doing. I speak for a social debris whose creating does not translate

into public reward or even a cogent public identity. Of course, there is

an easy reply: that we the debris have done nothing worthy of reward.

It was not Gurujis problem; but he had answers for the question

why?and we may ponder our problem in that light. If one has

something worth doing, if one has something to say, and one cannot

gain recognition for it, should you do it, and if so, why? Guruji would

say, you do it for God. Again, to respond, I have to be concessionary.

Wittgenstein wrote one of his posthumous books, Philosophical

Grammar, for God, he says. (Wittgenstein did not have the concept of

ones counsel with oneself.) Is doing it for God, a slogan which we find

in sophisticates like Wittgenstein and Rahner, prefigured by religioius

petition and sacrifice? It starts as an irrational destruction of produce to

gain a favor from Heaven, and ends as a far more vague offering to a

judge who is outside me and outside humanity. (Actually, sacrifice is far

more grim than that, there is a mortal spilling of blood to expiate sin

we dont have to pursue it that far.) For the normative outlook, this

offering to the god is absurd, as it was absurd of the Egyptians to build

pyramids for the next life. That leaves the judge of ones solitary

endeavors as oneself. But (as I said) if the person above myself is merely

I, the normative outlook appraises the judge to be reclusive, schizoid,

trivial and transitory.

Marx wanted to overcome solipsistic encapsulation in the 1844

Manuscripts by saying that what seems to be the most private and

idiosyncratic quest proves to be the most important for society. As

always, Marx rotates the payoff from life after death to the reality-types

society and future.

But what is the point of saying that my work will be found vitally

necessary by people a thousand years from now? Other people regard

my claim as presumptuous and preposterous. And how do I know that I

want to do the people one thousand years from now a favor? Pandit

Pran Nath said, dont release my records in India, they dont deserve

them. As for Marx, he was a humanist-fetishist; he did not conceive the

option of siding with attacking Martians. But we canyou can do it for

the committee of extra-terrestrial scientists, for example. But how do

you know what impresses the committee, where do you go to get your

grade?

I know what my answer is. Notwithstanding that we are dependent on

each other, each of us is alone anyway, intractably so. If you didnt

already know it, you will when the doctor tells you that you are incurably

ill. As adults we discover that we have separate fates, even if we wish we

didnt. When one finally meets the sensitive, aware people, one

discovers to ones shock that personal perspectives do not merge. The

perspectives of the sensitive, aware people remain disunited.

(Seemingly because of the way temperaments play out in ideologies.)

If one creates and there is no public applause, that only highlights the

condition we are in anyway. I will never sit across from another person

who is as dedicated as I am to what I find worth doing. When I give my

best, people are pointedly unconvinced by itfinding it baffling, or

wrong-headed and mischievous. The work is not just boring and

pointless to other people. In many cases, it would be disapproved. I

have no work that is worth doing that unites me with other people.

Every work that is worth doing isolates me.

For me, the problem solves itself; the answer is easy. Negligibly little in

this public arena is healing or dignifying or ennoblingin fact, these

ideals are derided to death in our milieu. (To be precise, the cultures

high priests deride human dignitywhile demanding that others extend

the utmost courtesy to them and theirs.) The content which is my joy in

life is rebuffed by the public, or cannot be shared with the public for one

reason or another. If I confined myself to what could be popular, there

would be nothing healing or dignifying or ennobling in my life. If I

refuse to hate myself and destroy myself, then I must devote myself to

unrecognized work.

Nothing that is important to me, nothing I want to do, is socially

applauded, at least not commensurately, not enough to provide a

livelihood. If I didnt do what was not recognized, then there would be

no time when I worked for my own satisfaction and euphoria.

If one made conviviality or fellowship the test of how one would occupy

oneself, one would not do anything worthwhile. One must work alone

all the more, with respect to that which has to be kept in confidence.

One does it for oneself, to mold, to cultivate oneself. One is self-

occupied because one is not being recruited for anything worth doing.

As well, there are profound reasons for doing the best you can, for

extending yourself. Even if nobody asks you to, even if you are not

applaudedI do not rule out having to store work for years because the

time has not come to make it public. Precisely because you go where

one shouldnt go, you have to be able to give the best account of

yourself. You cannot afford to know yourself to be a panderer, or to be

careless, irresponsible. You need the self-assurance, you need to stand

in confidenceyou need to to be reconciled with yourself.

I need to be able to say, Im doing the best I can, Im not playing to

approvaland I hope it means something to somebody besides me.

One should try to inch ones way forward in unwelcoming

circumstancesgranting that the work can only be inserted in the

record by insinuation, indirection, and so forth. What does it mean

when one fights to get something in the record in spite of its not being

understood and not being approved?

It is a tribute to the searing power of truth, to the truth that burns like a

branding iron. When one utters the truth, one changes the world

unilaterally. (As if one had left state secrets on a seat in the subway.

The truth in that case being that the state holds those things secret.) It

is quite distinct from seeking to exchange ideas with people. I choose

to talk at you; I do not wish you to talk to me. Of course the

renunciation of the exchange of ideas assumes the worst casebut that

may be all the situation warrants.

Postscript: the brend theory

A milieu in which art is traditional and aristocraticwhich offers, for

example, a vicarious encounter of grief conjured up with tones, and

thereby a healing or remediationdoes not push us in the direction of

the brend critique. Only when the European avant-garde empties art

out do we start toward the brend criticism. Only then do we notice that

the value I ascribe to art depends on its pleasing me, or affording me a

rewarding experience which is self-complete (never mind if it impels me

to behave in some manner afterwards). Then there is something out of

whack with embodying what pleases me in an object and exchanging it.

There is something out of whack with pouring my imagination into

inherited forms. There is something out of whack with the injunction to

purchase and consume my self-expression to be yourself.

Because of the complexity of sociality, there are borderline cases where

the brend theory comes across as rigid. (Our desire for vicarious

experience. Or architecture: the inescapability of collective taste or

public taste.) Nevertheless, the brend theory remains the most

important lesson which aesthetics refuses to learnand it applies to

traditional art even if the application is far more tangential than it is in

art whose abusiveness has reached crisis proportions.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Perotin Viderunt Omnes Soloists)Document20 paginiPerotin Viderunt Omnes Soloists)cesarino_ruiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amelia Cuni John Cage EssayDocument29 paginiAmelia Cuni John Cage EssayVictor CironeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conversations with Women in Music Production: The InterviewsDe la EverandConversations with Women in Music Production: The InterviewsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Other Minds 14Document40 paginiOther Minds 14Other MindsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Noise in and As MusicDocument259 paginiNoise in and As MusicDougy McDougerson100% (1)

- La Monte Young Selected WritingsDocument78 paginiLa Monte Young Selected WritingsFernando IazzettaÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Unnatural Attitude: Phenomenology in Weimar Musical ThoughtDe la EverandAn Unnatural Attitude: Phenomenology in Weimar Musical ThoughtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Missa Notre-Dame, MachautDocument23 paginiMissa Notre-Dame, MachautzasilaczÎncă nu există evaluări

- AutechreDocument8 paginiAutechreJuli?n r?osÎncă nu există evaluări

- 20th Century Music-Grad10Document21 pagini20th Century Music-Grad10Lanie Tamacio BadayÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Brief Summary of Indian MusicDocument5 paginiA Brief Summary of Indian MusicDeepak KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Terrible Freedom: The Life and Work of Lucia DlugoszewskiDe la EverandTerrible Freedom: The Life and Work of Lucia DlugoszewskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- John Cage - Experimental Music DoctrineDocument5 paginiJohn Cage - Experimental Music Doctrineworm123_123Încă nu există evaluări

- Beal Amy - Johanna BeyerDocument151 paginiBeal Amy - Johanna BeyerManuel Coito100% (1)

- William Basinski: The Music You Should Hear Series, #2De la EverandWilliam Basinski: The Music You Should Hear Series, #2Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Rose - Introduction To The Pitch Organization of French Spectral MusicDocument35 paginiRose - Introduction To The Pitch Organization of French Spectral MusicJose Archbold100% (1)

- Kenneth GaburoDocument2 paginiKenneth GaburoAlexander KlassenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bailey Improvisation ExcerptDocument12 paginiBailey Improvisation ExcerptMax SongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Banding Together: How Communities Create Genres in Popular MusicDe la EverandBanding Together: How Communities Create Genres in Popular MusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Improvisation and The Pattern Which Connects - Nachmanovitch (2007)Document14 paginiImprovisation and The Pattern Which Connects - Nachmanovitch (2007)Laonikos Psimikakis-ChalkokondylisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bring Da Noise A Brief Survey of Sound ArtDocument3 paginiBring Da Noise A Brief Survey of Sound ArtancutaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alvin Lucier: A CelebrationDe la EverandAlvin Lucier: A CelebrationAndrea Miller-KellerEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (2)

- Henry Flynt The Meaning of My Avantgarde Hillbilly and Blues Music 1Document15 paginiHenry Flynt The Meaning of My Avantgarde Hillbilly and Blues Music 1Emiliano SbarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bruce Holsinger - The Flesh of The Voice-Embodiment and The Homoerotics of Devotion in The Music of Hildegard Von BingenDocument35 paginiBruce Holsinger - The Flesh of The Voice-Embodiment and The Homoerotics of Devotion in The Music of Hildegard Von BingenTom ShootsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interview With Mani Kaul On Dhrupad MusicDocument4 paginiInterview With Mani Kaul On Dhrupad MusicaniruddhankÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clarity and Order in Sonic Youth's Early Noise Rock PDFDocument18 paginiClarity and Order in Sonic Youth's Early Noise Rock PDFalexandrosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chion - Dissolution of The Notion of TimbreDocument14 paginiChion - Dissolution of The Notion of Timbrecarlos perdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Henry Flynt The Art Connection My Endeavors Intersections With Art 1Document14 paginiHenry Flynt The Art Connection My Endeavors Intersections With Art 1Emiliano SbarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Postcolonial Repercussions: On Sound Ontologies and Decolonised ListeningDe la EverandPostcolonial Repercussions: On Sound Ontologies and Decolonised ListeningJohannes Salim Ismaiel-WendtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roig Francoli CH 3 PDFDocument22 paginiRoig Francoli CH 3 PDFLucia MarinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sonic Art - Recipes and ReasoningsDocument130 paginiSonic Art - Recipes and ReasoningsDimitra Billia100% (1)

- Treitler, Oral, Written, and Literature (Part I)Document5 paginiTreitler, Oral, Written, and Literature (Part I)Egidio PozziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Omniscience by Swans. Reviewed by Pieter Uys.Document8 paginiOmniscience by Swans. Reviewed by Pieter Uys.toypomÎncă nu există evaluări

- WISHART Trevor - Extended Vocal TechniqueDocument3 paginiWISHART Trevor - Extended Vocal TechniqueCarol MoraesÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Corpus-Based Method For Controlling Guitar Feedback: Sam Ferguson, Andrew Johnston Aengus MartinDocument6 paginiA Corpus-Based Method For Controlling Guitar Feedback: Sam Ferguson, Andrew Johnston Aengus Martinjpmac5Încă nu există evaluări

- CUT AND PASTE: COLLAGE AND THE ART OF SOUND - Kevin ConcannonDocument26 paginiCUT AND PASTE: COLLAGE AND THE ART OF SOUND - Kevin ConcannonYotam KadoshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Listening as Spiritual Practice in Early Modern ItalyDe la EverandListening as Spiritual Practice in Early Modern ItalyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Experimentalisms in Practice - Music Perspectives From Latin AmericaDocument369 paginiExperimentalisms in Practice - Music Perspectives From Latin AmericaRodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Earle Brown - Compositional ProcessDocument19 paginiEarle Brown - Compositional ProcessChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electronic Music Listening - Online SourcesDocument27 paginiElectronic Music Listening - Online SourcessolidsignalÎncă nu există evaluări

- After The Opera (And The End of TheDocument14 paginiAfter The Opera (And The End of TheJuliane AndrezzoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Metal Machine Music TechnologyDocument426 paginiMetal Machine Music TechnologyJoseph SalazarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cardew - Score. The Great Learning. Paraghraph 7Document1 paginăCardew - Score. The Great Learning. Paraghraph 7FromZero FromZeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Top 10 Compositions of The 21st CenturyDocument16 paginiTop 10 Compositions of The 21st CenturyEsteban RajmilchukÎncă nu există evaluări

- Musical Composers HungaryDocument46 paginiMusical Composers HungaryIvan Paul CandoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subjectivity in Auditory Perception: IX.1 First-Person NarrativesDocument16 paginiSubjectivity in Auditory Perception: IX.1 First-Person NarrativesReederessÎncă nu există evaluări

- Minimalism - Aesthetic, Style or TechniqueDocument33 paginiMinimalism - Aesthetic, Style or TechniqueDavid Angarita100% (2)

- Jean-Claude Resset - Computer Music Experiments 1964 - ...Document8 paginiJean-Claude Resset - Computer Music Experiments 1964 - ...DæveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hovhaness End Free Noh PlayDocument146 paginiHovhaness End Free Noh PlayDianaNGÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Vast Synthesising Approach: Interview With John AdamsDocument7 paginiA Vast Synthesising Approach: Interview With John AdamsRobert A. B. DavidsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3.3 Subtractive Synthesis: 3.3.1 Theory: Source and Modifi ErDocument15 pagini3.3 Subtractive Synthesis: 3.3.1 Theory: Source and Modifi ErMafeCastro1998100% (1)

- Contemporary Music Review: To Cite This Article: François Bayle (1989) Image-Of-Sound, or I-Sound: Metaphor/metaformDocument7 paginiContemporary Music Review: To Cite This Article: François Bayle (1989) Image-Of-Sound, or I-Sound: Metaphor/metaformHansÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nick Schillace - Master ThesisDocument254 paginiNick Schillace - Master ThesisMuzakfiles100% (1)

- Alternate Tuning Guide: Bill SetharesDocument96 paginiAlternate Tuning Guide: Bill SetharesPedro de CarvalhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2010 Ingold Ways of Mind-WalkingDocument10 pagini2010 Ingold Ways of Mind-WalkingjosefbolzÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Radical Idiom - Style and Meaning in The Guitar Music of Derek Bailey and Richard BarrettDocument93 paginiA Radical Idiom - Style and Meaning in The Guitar Music of Derek Bailey and Richard BarrettJanine IslandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Just Intonation PrimerDocument96 paginiJust Intonation Primeranalogues100% (1)

- David Novak 256 Metres of Space Japanese Music Coffeehouses and Experimental Practices of Listening 1Document20 paginiDavid Novak 256 Metres of Space Japanese Music Coffeehouses and Experimental Practices of Listening 1analoguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Derek Bailey Interview - July 1974Document3 paginiDerek Bailey Interview - July 1974analoguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art and The Politics of Public Housing Planners NetworkDocument3 paginiArt and The Politics of Public Housing Planners NetworkanaloguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ivendell Eader 42: Published Erratically Ever Since 1994 Winter 2010Document70 paginiIvendell Eader 42: Published Erratically Ever Since 1994 Winter 2010analoguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Derek Bailey Style Chords With Harmonics - Cochrane..Document4 paginiDerek Bailey Style Chords With Harmonics - Cochrane..analoguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poesia Visual !! Parr - Found - Poems - 1972Document17 paginiPoesia Visual !! Parr - Found - Poems - 1972Carlos ZatizabalÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Literature of Non Idiomatic Improvisation Poison Pie Publishing House PDFDocument27 paginiA Literature of Non Idiomatic Improvisation Poison Pie Publishing House PDFRui LeiteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unconstituted Praxis PDFDocument115 paginiUnconstituted Praxis PDFanaloguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Some Theses On Militant Sound Investigation or Listening For ADocument6 paginiSome Theses On Militant Sound Investigation or Listening For AanaloguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Noise in and As MusicDocument259 paginiNoise in and As MusicDougy McDougerson100% (1)

- Perec Georges The Machine PDFDocument61 paginiPerec Georges The Machine PDFanaloguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- PrimersampleDocument15 paginiPrimersamplepillen9Încă nu există evaluări

- Newmusicbox: Phill Niblock: Connecting The DotsDocument2 paginiNewmusicbox: Phill Niblock: Connecting The DotsanaloguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Lost Chord 2008 PDFDocument1.715 paginiThe Lost Chord 2008 PDFanalogues0% (1)

- The Book of Musical PatternsDocument76 paginiThe Book of Musical PatternsPedro Filho100% (1)

- Arts Edu RoadMap EsDocument90 paginiArts Edu RoadMap EsJorge BirruetaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unconstituted Praxis PDFDocument115 paginiUnconstituted Praxis PDFanaloguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alternate Tuning Guide: Bill SetharesDocument96 paginiAlternate Tuning Guide: Bill SetharesPedro de CarvalhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poesia Visual !! Parr - Found - Poems - 1972Document17 paginiPoesia Visual !! Parr - Found - Poems - 1972Carlos ZatizabalÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Jazz Guitar Chord DictionaryDocument63 paginiThe Jazz Guitar Chord Dictionarybruno di mattei97% (33)

- Ultimate Guitar Chord ChartDocument7 paginiUltimate Guitar Chord Chartanon-663427100% (71)

- Gerd Schraner - The Art of Wheel BuildingDocument103 paginiGerd Schraner - The Art of Wheel Buildingwellsy8983% (24)

- Derek Bailey Interview - July 1974Document3 paginiDerek Bailey Interview - July 1974analoguesÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Literature of Non Idiomatic Improvisation Poison Pie Publishing House PDFDocument27 paginiA Literature of Non Idiomatic Improvisation Poison Pie Publishing House PDFRui LeiteÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Custom BicycleDocument276 paginiThe Custom BicycleVytautas100% (6)

- Ali Arango: Villa-Lobos: Chôros 1Document12 paginiAli Arango: Villa-Lobos: Chôros 1Irina PakÎncă nu există evaluări

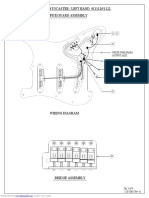

- Highway 1 Stratocaster / Left Hand 0111120/1122 Pickguard AssemblyDocument1 paginăHighway 1 Stratocaster / Left Hand 0111120/1122 Pickguard AssemblyJurandir LuizÎncă nu există evaluări

- 서편제 (1993) 복원본 Sopyonje (Seopyeonje) Restoration VerDocument31 pagini서편제 (1993) 복원본 Sopyonje (Seopyeonje) Restoration VerchanakawidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Always With MeDocument2 paginiAlways With MeChen QiaochuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solemnity of The Immaculate Conception - Sing To The Lord A New SongDocument1 paginăSolemnity of The Immaculate Conception - Sing To The Lord A New SongRonilo, Jr. CalunodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lower Altissimo Register - Alternate Fingering Chart For Boehm-System Clarinet - The Woodwind Fingering GuideDocument4 paginiLower Altissimo Register - Alternate Fingering Chart For Boehm-System Clarinet - The Woodwind Fingering GuidepascumalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reviewer 4th MapehDocument3 paginiReviewer 4th MapehMelanie B. DulfoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Field DemonstrationDocument1 paginăField DemonstrationJoan Marie PeliasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Buddha Bar, Vol. 5 Track ListingDocument1 paginăBuddha Bar, Vol. 5 Track ListingAmabilul FãnicãÎncă nu există evaluări

- 100 Greatest Rock Albums of TheDocument8 pagini100 Greatest Rock Albums of ThealanbogotaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workbook Smart Choice Unit 4.Document5 paginiWorkbook Smart Choice Unit 4.Raycelis Simé de LeónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Do Re MiDocument1 paginăDo Re MincguerreiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Islands 6 Pupil S BookDocument95 paginiIslands 6 Pupil S BookMichael GarbeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tim Lerch - The Melodic Jazz Guitar Chord Dictionary Modern Jazz GuitaristDocument202 paginiTim Lerch - The Melodic Jazz Guitar Chord Dictionary Modern Jazz Guitaristhq7sxpk25fÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gerineldo PVG ScoreDocument6 paginiGerineldo PVG ScoreMartin RichardsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Romance LanguagesDocument26 paginiRomance LanguagesIskender IskenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wonderwall Chords: by OasisDocument5 paginiWonderwall Chords: by OasisRaiza SarteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pack Musicas Mta 800mscDocument44 paginiPack Musicas Mta 800mscKauann SilvaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Second Cup of CoffeeDocument2 paginiSecond Cup of CoffeejmsklarÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Id 1bDocument124 paginiEnglish Id 1bJoseph_Lds76% (51)

- Blues For Lester PDFDocument6 paginiBlues For Lester PDFZero HeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journalism of ManagementDocument23 paginiJournalism of ManagementAndre BenayonÎncă nu există evaluări

- SESSION GUIDE Grade 7-MUSIC (Form)Document13 paginiSESSION GUIDE Grade 7-MUSIC (Form)Pilo Pas KwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- SDO Navotas Music9 Q2 Lumped - FVDocument50 paginiSDO Navotas Music9 Q2 Lumped - FVMarie TiffanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dancesport Syllabus 10 DanceDocument6 paginiDancesport Syllabus 10 DanceBryan Mon RosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fantasia Di Concerto (Boccalari)Document6 paginiFantasia Di Concerto (Boccalari)Antonio DelgadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Expecting An Insider Audience (767) Überarbeitet Mesenbrock KopieDocument12 paginiExpecting An Insider Audience (767) Überarbeitet Mesenbrock KopieSarah MesenbrockÎncă nu există evaluări

- Herbert L. Clarke Setting Up Drills For The Trumpet (Calisthenic Exercises)Document19 paginiHerbert L. Clarke Setting Up Drills For The Trumpet (Calisthenic Exercises)Rênnisson WillgnerÎncă nu există evaluări

- One Punch Man TABDocument3 paginiOne Punch Man TABRenato Müller100% (1)

- Juslin Sloboda HANDBOOK OF MUSIC AND EMOTION THEORY, RESEARCH, APPLICATIONSDocument5 paginiJuslin Sloboda HANDBOOK OF MUSIC AND EMOTION THEORY, RESEARCH, APPLICATIONSCRISTINA AIESTA YUSTEÎncă nu există evaluări