Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Repatriation of Expat Employees, Knowledge Transfer, Org Learning

Încărcat de

Tiffany WigginsDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Repatriation of Expat Employees, Knowledge Transfer, Org Learning

Încărcat de

Tiffany WigginsDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Repatriation, Knowledge, and Learning

1

Repatriation of Expatriate Employees, Knowledge Transfer, and Organizational Learning: What Do We

Know?

Tania Nery Kjerfve and Gary N. McLean

Texas A&M University, USA

ABSTRACT: Repatriation is a key troublesome moment of the international assignment of employees.

Companies do not always have in place policies and procedures to help with the integration of returning

employees and their families. Repatriates often face severe challenges to reintegrate back to the headquarters

organization and to the home culture, and resent the lack of support provided by organizations. The knowledge

and learning possessed by repatriates goes largely underutilized because of the lack of mechanisms and

processes to unveil and circulate such knowledge to other members of the organization. This paper provides an

interpretive literature review of articles published on repatriation, knowledge transfer, and organization learning

1999-2009. It also provides suggestions on specific measures to be adopted by corporations to assist in the

reintegration of repatriates to enhance knowledge sharing and learning throughout the organization.

Keywords: Repatriation, Knowledge Transfer, Knowledge Sharing, Organizational Learning

Repatriation is a key troublesome moment in the international assignment of employees in global

corporations. The conclusion of an assignment and the transfer of the employee and his/her family back to the

organization and to the home culture are often preceded by moments of high anxiety. The situation is often

aggravated due to the fact that many corporations do not have policies and procedures to prepare for the return

of expatriates and also do not understand the repatriation time as an important period of the cycle of the

international assignment (Yeaton & Hall, 2008).

Expatriate employees are often a major source of knowledge and expertise among global corporations;

their circulation among subsidiary offices can potentially transfer, absorb, and circulate organizational

knowledge between offices, thus enhancing learning and expertise at overseas offices during the assignment,

and also at the headquarters office after the termination of the international assignment (IA). Expatriates,

however, are often the most costly employees in the organization, with the total cost estimate of the

international transfer representing approximately three to five times the annual salary of their domestic

counterparts (Shaffer, Harrison, & Gilley, 1999). Global corporations do not always succeed in establishing

policies and practices to make good use of such expensive employees after the termination of the IA. In many

cases, the knowledge acquired by the expatriate manager does not widely circulate among stakeholders at the

headquarters organization once the manager returns home from the assignment (Stroh, Gregersen, & Black,

2000). The repatriation phase is often a period of high stress for returning expatriates and their families; it is

estimated that between 20% and 50% of returning employees leave the corporation within one year of their

return to the home country (Yeaton & Hall, 2008).

Purpose of Paper

The purpose of this paper is to address the potential benefits of the use of expatriate employees to

enhance global knowledge and organizational learning in multinational corporations. With this intent, we

conducted a literature review of articles published in the last decade, in which the main or subsequent focus was

the relationship between the use of expatriate employees and the enhancement of organizational learning in

MNCs. We concentrated our analysis on the repatriation phase or the re-entry of the expatriate employee to the

headquarters organization. As a model of interpretative literature review, we used some of the techniques

proposed by Ardichvili and J ongle (2009). The use of the literature as research data proposed by the

Repatriation, Knowledge, and Learning

2

interpretative literature review method can help us sort through the research findings achieved so far regarding

the repatriation of international assignees and knowledge transfer and organizational learning in global

corporations.

Methods

A preliminary general literature search was conducted making use of several databases available at a

major U.S public Research 1 university. Our search concentrated exclusively on journal articles published

1999-2009. We have not included in our search books, conference proceedings, or dissertations. The keywords

used at a first stage were repatriates, repatriation, organizational learning, knowledge transfer, and

multinationals. Articles were selected based on direct or indirect relevance to the research topic. After a quick

reading of the abstract of the retrieved articles, our search identified 16 articles. A majority of the articles

retrieved were identified by the following databases: EconLit, Wilson Business Abstracts, and Web of Science.

The process utilized is a well-tested library search technique called pearl growing; this technique suggests the

identification of relevant articles to be adopted as a platform for identifying terms and keywords more

commonly used to define the research topic (Schlosser, Wendt, & Nail-Chiwetalu, 2006).

From the 16 relevant articles initially retrieved, we identified keywords, terms, databases, and

publications that appeared more frequently. The journals most often cited in our search were Journal of World

Business, Journal of International Business Studies, Human Resource Management, and International Journal

of Human Resource Management. This process did not identify any additional articles, only duplicates of

articles initially retrieved.

We next proceeded to search for additional material in the most cited journal of our search, the Journal

of World Business. We concentrated our search on the last five years, from 2005-2009, based on the fact that

our initial search retrieved a majority of articles published within this time period; 15 of the 16 retrieved articles

were published 2005-2009. This second search also did not retrieve any articles with direct reference to our

research topic. We then proceeded to search for additional articles making use of Google Scholar. From this

search, we identified 6 more articles. Thus, our investigation and analysis were based on these 24 retrieved

articles.

Repatriation of Expatriates and High Turnover Rates: Some Causes

The high turnover rates among returning expatriates have inspired the literature on repatriation to

address some of the reasons causing this problem. Much of the literature addresses issues related to the reasons

why expatriates leave their firms after their return from IAs. It is estimated that the turnover rate among

expatriates is 20% to 50% within the first year of the employee returning from overseas (Stroh, Gregersen, &

Black, 2000; Tyler, 2006; Yeaton & Hall, 2008). Repatriation programs are still not widely adopted by global

corporations. Companies seldom understand the need to promote any special program to prepare returning

expatriates to reenter both their home culture and the headquarters workplace.

The repatriation time is a moment in the expatriation cycle plagued with uncertainties and anxieties for

expatriates and their families. Repatriates often suffer from reverse cultural shock, which can be even more

severe than the cultural shock faced during the initial months of expatriation. Corporations rarely offer special

services to reintegrate expatriates to the organization and, further, often maintain little contact with expatriates

during the IA. Expatriates remain largely out of sight and out of mind by managers, HR departments, and

colleagues at the headquarters organization during IAs (Gregersen & Black, 1995). Consequently, returning

employees often face problems adjusting to their home culture and headquarters organization, which influences

negatively their satisfaction on the job and their intention to remain in the corporation. A large number of

Repatriation, Knowledge, and Learning

3

articles retrieved for this project dealt with the topic of employee adjustment, job satisfaction, and its

consequences in high turnover rates (Table 1).

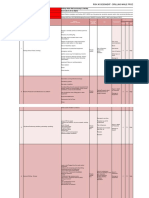

Table: Articles on Repatriation, Knowledge Transfer, and Learning (1999-2000).

Author(s) Year Type Method Topic

Stroh, Gregersen, & Black 2000 Empirical Quantitative Employee retention

United States

Berthoin-Antal, A 2000 Empirical Qualitative Organizational knowledge

Germany

Berthoin-Antal, A 2001 Empirical Qualitative Organizational knowledge

Germany

Lazarova & Caligiuri 2001 Empirical Quantitative Employee turnover

US -Canada

Linehan & Scullion 2002 Empirical Qualitative Employee adjustment

Europe

Bossard & Peterson 2005 Empirical Qualitative Employee adjustment

United States

Fink, Meierewert, & Rohr 2005 Empirical Qualitative Organization knowledge

Austria

Lazarova & Tarique

2005 Conceptual Knowledge transfer

Stevens and colleagues 2006 Empirical Quantitative J ob satisfaction

J apan

Tyler 2006

Non referee Employee turnover

Hyder & Lovblad 2007 Conceptual Employee retention

Lee & Liu 2007 Empirical Quantitative Employee retention

Taiwan

Makela 2007 Empirical Qualitative Knowledge sharing

Sweden/Finland

Newton, Hutchins, &

Kabanoff

2007 Empirical Mixed Repatriation policies

Australia

Vidal, Valle, Aragn, &

Brewster

2007 Empirical Quantitative Employee adjustment

Spain

Vidal, Valle, & Aragn 2007a Empirical Quantitative J ob satisfaction

Spain

Vidal, Valle, & Aragn 2007b Empirical Qualitative Employee adjustment

Spain

Kohonen 2008 Empirical Qualitative Employee retention

Finland

Osman-Gani & Hyder 2008 Empirical Quantitative

Yeaton & Hall 2008 Non referee Employee turnover

Crowne 2009 Conceptual Knowledge transfer

Furuya & colleagues 2009 Empirical Quantitative Learning transfer

J apan

Jassawalla & Sashittal 2009 Empirical Qualitative Strategic policies

United States

Oddou, Osland,&

Blackeney

2009 Conceptual Organization knowledge

Repatriation, Knowledge, and Learning

4

A majority of studies retrieved were based on the experience of employees across the globe and have

benefited from earlier studies in the 1980s and 1990s focused mostly on the experience of expatriates from the

North American corporate environment (Adler, 1981; Gregersen & Black, 1995). Of the articles retrieved, four

referred to North American companies, another fourteen referred to corporations across the globe i.e.,

Australia, Austria, Europe, Finland, Germany, J apan, Spain, Singapore, Sweden, and Taiwan (Berthoin-Antal,

2000 & 2001; Fink, Meierewert, & Rohr, 2005; Furuya, Stevens, Bird, Oddou, & Mendenhall, 2009; Kohonen,

2008, Lee & Liu, 2007; Linehan & Scullion, 2002; Makela, 2007; Newton, Hutchins, & Kabanoff, 2007;

Osman-Gani & Hyder, 2008; Stevens, Oddou, Furuya, Bird, & Mendenhall, 2006; Vidal, Valle, Aragon &

Brewster, 2007; Vidal, Valle, & Aragon, 2007a & b).

The experience of reverse cultural shock is advanced as one of the main factors hindering employee

adjustment to the home culture and to the headquarters organization. This experience tends to be more acute

because of its unexpected component. During IAs expatriates and their families assimilate the overseas culture,

the experience of living and working abroad often alters mental maps and changes behavioral routines (Stroh,

Gregersen, & Black, 2000), thus creating difficulties for readjustment to the home culture. Reverse culture

shock is often greater for individuals from homogeneous cultural backgrounds who were forced to make deeper

adjustment to their behavior while overseas, and who, in turn, have to make major adjustments in order to revert

back to their old behavior upon repatriation (Stroh, Gregersen, & Black, 2000). In the workplace, expatriate

employees lose contact with the day-to-day operations of their organizations and relinquish contact with the

social network of colleagues and supervisors in the domestic organization (Lazarova & Caligiuri, 2001; Linehan

& Scullion, 2002; Vidal, Valle, Aragn, 2007). Upon reentry, those social ties need to be reestablished, and new

technologies and procedures need to be relearned. Expatriates and their families often take from six months to

one year to readjust back to the daily operation of their organizations and to their home country cultures

(Linehan & Scullion, 2002), and social networks, both personal and in the workplace, often take a long time to

reestablish, sometimes up to one year (J assawalla & Sashittal, 2009). In the meanwhile, the lack of social

networks hinders the adjustment of the returning employees back to the organization.

For female executives, the repatriation phase poses even more acute problems. Women often suffer

major personal and professional stresses during the re-entry phase because of having to assume the primary

responsibility of assisting with the reintegration of the family into the home culture. In addition, they also suffer

with the lack of role models and mentors at the headquarters organization to assist in their career development

path (Linehan and Scullion (2002).

Employees also change and mature during the experience of living and working abroad. Kohonen

(2008) identified that IAs are often a period of profound personal and professional growth for expatriates; it

potentially cause changes in the expatriates sense of self and personal identity, in particular among individuals

who experienced high levels of professional responsibility and independence. IAs promote different impacts in

different types of personalities; individuals with greater involvement with the host cultures and with high

independence at work often emerge from IAs with an increased sense of professional self-confidence and higher

expectations and ambitions in regards to their future careers. They often develop a greater commitment to their

subjective career rather than to their organizational career, and become more prone to launch boundary-less

careers and to seek challenging professional opportunities in other organizations. Expatriates with less

involvement with the host culture and/or less managing responsibility at work, have an easier time readjusting

back to their home cultures and headquarters organization. It is thus fundamental for corporations to assess the

needs of their repatriates employees in order to develop practices and professional opportunities to fit the

employees objectives and aspirations.

Repatriation is largely treated in an ad hoc manner. Expatriates are transferred back home without much

previous warning, preparation, and without a clear career path at the organization (Yeaton & Hall, 2008). There

Repatriation, Knowledge, and Learning

5

is often disconnect between the expatriates perception and the corporation use of IAs (J assawalla & Sashittal,

2009; Tyler, 2006). For employees IAs are perceived as a career development tool for future leadership

positions. For corporations IAs are used for numerous purposes knowledge transfer, position filling, control of

subsidiaries, and leadership development (J assawalla & Sashittal, 2009). Among Australian organizations,

repatriation programs are adopted mostly when dealing with IAs for the purpose of leadership development

(Newton, Hutchins, & Kabanoff, 2007). Expatriates often are placed in lateral positions upon returning to the

headquarters organization; they also do not experience the same level of autonomy or utilize their

knowledge/skills. (Berthoin-Antal, 2001; J assawalla & Sashittal, 2009; Lazarova & Caligiuri, 2001; Linehan &

Scullion, 2002; Yeaton & Hall, 2008). Recently internationalized firms are not always able to create challenging

positions to repatriates (Fink, Meierwert, & Rohr, 2005).

There seems to be a strong connection between employee adjustment, job satisfaction, and

organizational commitment towards promoting job retention among returning expatriates (J assawalla &

Sashittal, 2009; Lazarova & Caligiuri, 2001; Lee & Liu, 2007; Stevens, Oddou, Furuya, Bird, & Mendenhall,

2006; Stroh, Gregersen, & Black, 2000; Vidal, Valle, Aragn & Brewster, 2007; Vidal, Valle, & Aragn, 2007

a & b). The existence or perception of practices within the corporation to assist in the repatriation of employees

affects positively the intention of employees to remain in the corporation. Employees often develop negative

attitudes towards their corporations when they perceive a lack of support and appreciation for their dedication,

hard work, knowledge, and skills; this perception is often mostly subjective and not based on objective

assessments of repatriation support and practices in the organization (Lazarova & Caligiuri, 2001). Repatriates

often develop work and non-work expectations that they wish corporations to address; only when their

expectation are met and there is an alignment between a positive repatriate experience and a fulfillment of

motives employees remain committed to their organization and keep their jobs (Stroh, Gregersen, & Black,

2000; Hyder & Lovblad, 2007). Some of the policies and procedures well regarded by returning expatriates and

cited as having positive effect on the retention of expatriate employees are:

(1) Provide debriefing opportunities prior to and upon the termination of IAs to prepare for the day-to-

day changes in the headquarters office (Berthoin-Antal, 2001; Bossard & Peterson, 2005; Lazarova

& Caligiuri, 2001; Osman-Gani & Hyder, 2008; Tyler, 2006).

(2) Create training for repatriates and families to ease reverse cultural shock (J assawalla & Sashittal,

2009; Osman-Gani & Hyder, 2008; Vidal, Valle, & Aragn, 2007a; Yeaton & Hall, 2008).

(3) Offer career planning and path for repatriates (Berthoin-Antal, 2001; Bossard & Peterson, 2005;

J assawalla & Sashittal, 2009; Osman-Gani & Hyder, 2008; Lazarova & Caligiuri, 2001; Tyler,

2006; Vidal, Valle, & Aragn, 2007a; Yeaton & Hall, 2008).

(4) Offer a written agreement to address compensation and future employment issues (Lazarova &

Caligiuri, 2001).

(5) Provide promotion upon return from IAs (Vidal, Valle, & Aragn, 2007a).

(6) Assign a mentor to assist expatriates during and after the international assignment (J assawalla &

Sashittal, 2009; Lazarova & Caligiuri, 2001; Tyler, 2006; Yeaton & Hall, 2008).

(7) Provide clear information about job placement possibilities in order to address work expectations of

returning expatriates (Vidal, Valle, Aragn, 2007a).

Empirical studies from around the globe reveal preferences regarding repatriation practices. Among

Spanish employees, mentorship relationships were not regarded very important by returning employees,

indicating perhaps a low quality of mentoring programs in Spanish-based organizations (Vidal, Valle, Aragn,

& Brewster, 2007). Among Taiwanese and J apanese employees, high turnover rates were associated with the

ability of employees to readjust to the organization, reflecting the stricter membership of work teams and

groups in Confucian cultures (Lee & Liu, 2007; Stevens et al., 2006). Osman-Gani & Hyder (2008) identified

Repatriation, Knowledge, and Learning

6

preferences regarding content, duration and type of training among individuals of different nationalities;

J apanese repatriates preferred short one day long sessions, of classroom instruction, focusing on reverse culture

shock. German and Singaporeans favored workshop/seminar and case study and video-based training dealing

with human resource issues.

Knowledge Transfer and Learning

Expatriate employees are often a major source of knowledge in international corporations; their

circulation among subsidiary offices can supposedly increase the knowledge and learning among offices of the

international firm (Berthoin-Antal, 2000). The topic of knowledge transfer and organization learning resulting

from repatriation is still under-researched. Only few articles have unveiled data regarding the actual transfer of

knowledge upon the termination of IAs (Oddou et al., 2009). Many articles at this point are conceptual. Of the

articles utilized here regarding knowledge resulting from repatriation five are empirical and three are

conceptual.

Knowledge transfer in corporations is not always a straightforward task. Organizational knowledge is a

multifaceted concept and there are different types of knowledge (Kostova, 1999). IAs are characterized by

transferring both explicit - referring to technical aspects - and tacit knowledge -referring to more complex and

deeper embedded knowledge (Kostova, 1999). Repatriates often possess large amount of tacit knowledge,

which is extremely important for global corporations as it provides a deeper understanding of the business

operations and cultural dealings in international environments (Lazarova & Tarique, 2005).

Knowledge resulting from repatriation often goes under-utilized, because among other factors, the

inability of corporations to place returning employees in professional positions where they could better

disseminate the knowledge and learning acquired overseas. Other factors also influence the process of

knowledge transfer and learning after repatriation. Internal stickiness hinders the ability of recipients at the

headquarters organization to absorb knowledge (Szulanski, 1996); social, organizational and individual factors

also limit knowledge sharing at MNCs (Kostova, 1999).

Expatriates prolonged engagement during IAs often allow for richer relationships among employees,

thus increasing the possibility of knowledge sharing to occur with different groups of individuals at different

locations of the global firm (Makela, 2007). Such possibility, however, is hindered by pressures and limitations

imposed on repatriates by their own corporations. Rigid structures and cultures do not promote and allow

knowledge sharing (Berthoin-Antal, 2001).

Expatriates often acquired different types of knowledge that have the potential of being converted to

organization learning (Berthoin-Antal, 2000; Fink, Meierewert, & Rohr, 2005). However, such learning will

only happen if processes are in place to unveil expatriates tacit knowledge in order to allow it to surface to

other members of the organization (Berthoin-Antal, 2001). Corporations need to view repatriation as a

competency-based opportunity to renew its competencies; it need thus to create opportunities for new

knowledge to be absorbed and circulate in the organization. Formal and informal processes need to be created to

allow for knowledge sharing taking place. Rich mechanisms of communications and interaction among

returning expatriates and other members of the organization i.e. global teams, coaching and mentoring

relationships - also allows for more knowledge sharing to take place post repatriation (Furuya et al., 2009;

Lazarova & Tarique, 2005),

Oddou, Osland, and Blakeleys (2009) argued that repatriation knowledge is in itself a knowledge

creation process that is intermediated by a resocialization process of repatriates; knowledge sharing will only

occur when expatriates feel valued by the organization and are seen by others as valuable reservoirs of

knowledge; such recognition will allow repatriates to few more willing to share their knowledge and will allow

other members of the organization to few more open to absorb such knowledge. Corporations can assist this

Repatriation, Knowledge, and Learning

7

process by promoting feedback seeking behaviors and social networks in order to facilitate the reintegration of

repatriates to the organization (Crowne, 2009).

Discussion

Based on the literature review, it is evident that the experience of living and working abroad, in most

parts, greatly affect the lives and alters the expectations of expatriate employees. Returning employees and their

families often suffer from reverse cultural shock and require assistance and preparation prior to their

reintegration to the home culture and headquarters organization. The lack of repatriation policies and

procedures hinders the employees adjustment to the organization and affects their satisfaction on the job and

their commitment and loyalty to the organization. The high turnover rates observed among repatriates is a direct

consequence of the lack of support and professional opportunities available to expatriates upon termination of

IAs.

For expatriates, IAs often represent a career development move that will pay dividends upon their return

to the headquarters organization. Corporations, however, do not always view the expatriation as a commitment

to further career advancement of employees upon their return. This strong disconnect causes great

dissatisfaction among returning employees who find themselves placed in lateral positions to their view not in

accordance with the amount of expertise, knowledge, and development acquired abroad. Corporations often fail

to recognize that their competitiveness largely depends on the quality of their human resource, thus making it

paramount the retention, successful reintegration, and circulation of the knowledge acquired by expatriate

employees.

There is a strong connection between employee adjustment, job satisfaction and organizational

commitment towards promoting reintegration of expatriate employees. Corporations cannot thus shy away from

developing repatriation policies; they need to strive to promote debriefing sessions and training opportunities to

ease the impact of reverse cultural shock among expatriates and their families, they need to provide clear

information about job placement possibilities, and need to strive to create a career path for employees in order

to accommodate their newly acquired knowledge and skills and their professional ambitions. Those

mechanisms, however, need to take in consideration the local and cultural context of each corporation and of

their employees. Practices developed in some local context may not always apply well to other locations in

which the same processes are not in place or function at a different level.

Repatriate employees have the potential of acting as a major source of knowledge for global

corporations. They could be key players in helping corporations gain and maintain competitive advantage in the

global market. Much of the knowledge acquired by expatriates goes largely untapped because of its tacit

component, which keeps it often deeply ingrained and requires active programs and processes to make it surface

to the individual and to the group. Repatriates need sense making experiences in order to fully grasp the extent

of the knowledge acquired and in order to be able to make it applicable to his/her new environment. Those

activities and processes are also fundamental for the sharing of this new acquired knowledge with other

individuals across the organization, leading ultimately to become part of the repertoire of knowledge available

throughout the organization.

Implications for Practice

HRD professionals can be of important assistance in setting up programs and processes to assist in the

reintegration of expatriate employees back to the headquarters organization. The core tenets of HRD training

and development, career development, and organization development- may assist global and international

corporations in the well handling of expatriates through the creation of mechanisms both for the benefit of the

individual, the group, and the organization. Training interventions have the potential to be ideal tools to assist

Repatriation, Knowledge, and Learning

8

with the reintegration of repatriates and their families to the home and headquarters culture. Training

opportunities should include cross-cultural training (to deal with the effects of reverse cultural shock), practical

training (to inform of changes occurred in the headquarters office during the absence of the repatriate

employee), technology and production training (to update employees on advances and changes having taken

place in the headquarters office).

Career development interventions are essential for repatriate employees because of the high turnover

rates frequently observed among returning expatriates. HRD professionals need to design interventions that

address the high professionals aspirations and expectations of returning expatriates; those interventions need to

engage repatriates in creating a career path that could accommodate their advanced knowledge and skills and

that would address their needs of challenging and rewarding professional opportunities.

Organization development interventions can also assist organizations with the reintegration of

repatriates; OD interventions can provide mechanisms to identify the missing component in the structure of

organizations that is hindering the adjustment of employees back to the organization and can assist in

redesigning new structures to make sure such reabsorbing of returning expatriates is done in a more efficient

manner. OD interventions can also enhance the trust between repatriates and headquarters employees through

team building activities designed to reintegrate returning employees back to the work groups and units in the

headquarters organization. OD interventions can also assist organizations in supporting a learning culture in

which the repatriates knowledge and experience is shared among all employees in the organization and is

utilized toward organization development, growth, and increased competitiveness.

Recommendations for Future Research

The literature review approach adopted in this paper allowed us to identify key issues concerning the

repatriation of employees and to propose some measures that could be adopted to assist corporations in the

retention of repatriates. More empirical studies on repatriation will identify the suitability of some of the

proposed measures and its applicability to different cultural settings. Both quantitative and qualitative

approaches should be applied to the study of repatriation as those would allow a different dimension to the issue

of repatriation; it is also suggested that studies on repatriation promote a longitudinal approach in which the

whole process is viewed over an extended period of time in order to measure the utility of some of the proposed

suggestions towards enhancing adjustment and retention of employees and the sharing of knowledge and

learning in organizations.

Conclusion

Repatriation policies are essential to assure the adjustment and retention of expatriate employees.

Organizations that operate in the international market cannot shy away from adopting repatriation policies and

practices to assure that they retain their most important asset their cadre of global managers. Returning

expatriates are likely to leave their organization when they perceive that it fails to develop mechanisms and

practices to reward, utilize and circulate their newly acquired knowledge and skills. Structures and processes

need to be in place in order to allow the repatriates knowledge and expertise to be shared with other and

become embedded in the organization. It is the knowledge possessed by these key individuals that is the main

asset for corporations to compete in the global market.

References

Adler, N. (1981). Re-entry: Managing cross-cultural transitions. Group and Organization Studies, 7, 341-356.

Repatriation, Knowledge, and Learning

9

Ardichvili, A., & J ongle, D. (2009). Ethical business cultures: A literature review and its implications for HRD.

Human Resource Development International, 8, 223-244.

Berthoin-Antal, A. (2000). Types of knowledge gained by expatriate managers. Journal of General

Management, 26, 32-51.

Berthoin-Antal, A. (2001). Expatriates contribution to organization learning. Journal of General Management,

26, 62-84.

Bossard, A., & Peterson, R. B. (2005). The repatriate experience as seen by American expatriates. Journal of

World Business, 40, 9-28.

Crowne, K.A. (2009). Enhancing knowledge transfer during and after international assignments. Journal of

Knowledge Management, 13, 134-147.

Fink, G., Meierewert, S., & Rohr, U. (2005). The use of repatriation knowledge in organizations. Human

Resource Planning, 28, 30-36.

Furuya, N., Stevens, M., Bird, A., Oddou, G., & Mendenhall, M. (2009). Managing the learning and transfer of

global management competence: Antecedents and outcomes of J apanese repatriation effectiveness.

Journal of International Business Studies, 40, 200-215.

Gregersen, H. S., & Black, J . S. (1995). Keeping high performers after international assignment: A key to

global executive development. Journal of International Management, 1, 3-31.

J assawalla, A. R., & Sashittal, H. C. (2009). Thinking strategically about integrating repatriated managers in

MNCs. Human Resource Management, 48, 769-792.

Kohonen, E. (2008). The impact of international assignments on expatriates identity and career aspirations:

Reflections upon re-entry. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 24, 320- 329.

Kostova, T. (1999). Transnational transfer of strategic organizational practices: A contextual perspective.

Academy of Management Review, 24, 308-324.

Hyder, A., & Lovblad, M. (2007). The repatriation process a realistic approach. Career Development

International, 12, 264-281.

Lazarova, M., & Caligiuri, P. (2001). Retaining repatriates: the role of organizational support practices. Journal

of World Business, 36, 389-401.

Lazarova, M., & Tarique, I. (2005). Knowledge transfer upon repatriation. Journal of World Business, 40, 361-

373.

Lee, H.W., & Liu, C. H. (2007). An examination of factors affecting repatriates' turnover intentions.

International Journal of Manpower, 28, 122-134.

Linehan, M., & Scullion, H. (2002). Repatriation of European female corporate executive: an empirical study.

International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13, 254-267.

Makela, K. (2007). Knowledge sharing through expatriate relationships. International Studies of Management

& Organization, 37, 108-125.

Newton, S., Hutchings, K., & Kabanoff, B. (2007). Repatriation in Australian organisations: Effects of

functions and value on international assignment on program scope. Asia Pacific Journal of Human

Resources, 45, 295-313.

Oddou, G., Osland, J ., & Blakeney, R. (2009). Repatriation Knowledge: variables influencing the transfer

process. Journal of International Business Studies, 40, 181-199.

Osman-Gani, A., & Hyder, A. (2008). Repatriation readjustment of international managers. An empirical

analysis of HRD interventions. Career Development International, 13, 456-475.

Shaffer, M. A., Harrison, D. A., & Gilley, K. M. (1999). Dimensions, determinants, and differences in the

expatriate adjustment process. Journal of International Business Studies, 30, 557-581.

Schlosser, R., Wendt, R., Bhavnani, S., & Nail-Chiwetalu, B. (2006). Use of information-seeking strategies for

developing systematic reviews and engaging in evidence-based practice: the application of traditional

Repatriation, Knowledge, and Learning

10

and comprehensive Pearl Growing. A Review. International Journal of Language and Communication

Disorder, 41, 567-582.

Stroh, L. K., Gregersen, H. B., & Black, J . S. (2000). Triumphs and tragedies: expectations and commitments

upon repatriation. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11, 681-697.

Stevens, M., Oddou, G., Furuya, N., Bird, A., & Mendenhall, M. (2006). HR factors affecting repatriate job

satisfaction and job attachment for J apanese managers. International Journal of Human Resource

Management, 17, 831-841.

Szulanski, G. (1996). Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm.

Strategic Management Journal, 17, 27-43.

Vidal, M. E. S., Valle, R. S., Aragn, M. I. B., & Brewster, C. (2007). Repatriation adjustment process of

business employees: Evidence from Spanish workers. International Journal of Intercultural Relations,

31, 317-337.

Vidal, M. E. S., Valle, R. S., & Aragn, M. I. B. (2007a). Antecedents of repatriates job satisfaction and its

influence on turnover intentions: Evidence from Spanish repatriated managers. Journal of Business

Research, 60, 1272-1281.

Vidal, M. E. S., Valle, R. S., & Aragn, M.I.B. (2007b). The adjustment process of Spanish repatriates: a case

study. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18, 1396-1417.

Tyler, K. (2006). Retaining repatriates. HR Magazine, 51, 97-102.

Yeaton, K., & Hall, N. (2008). Expatriates: Reducing failure rates. Journal of Corporate Accounting &

Finance, 75-78.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Sevis Id:: Department of Homeland SecurityDocument3 paginiSevis Id:: Department of Homeland SecurityButssy100% (1)

- PROFILE Installation GuideDocument34 paginiPROFILE Installation GuideAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Well ArchitectDocument1 paginăWell ArchitectSandesh ChavanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handbook of Criminal Justice AdministrationDocument520 paginiHandbook of Criminal Justice AdministrationGarry Grosse100% (3)

- Daily Lesson Log - Observation COOKERY (9) ObservedDocument2 paginiDaily Lesson Log - Observation COOKERY (9) ObservedGrace Beninsig Duldulao100% (6)

- Summary of The OJT ExperienceDocument3 paginiSummary of The OJT Experiencejunjie buligan100% (1)

- OPeration & Maintenance ManualDocument23 paginiOPeration & Maintenance ManualMohammed Esheaba100% (1)

- API Assignment Q2Document2 paginiAPI Assignment Q2Salman Farooq50% (2)

- BCG What Really Matters For A Premium IPO Valuation July 2018 - tcm9 196864Document8 paginiBCG What Really Matters For A Premium IPO Valuation July 2018 - tcm9 1968649980139892Încă nu există evaluări

- Quality, Management Plan - TemplateDocument9 paginiQuality, Management Plan - TemplateEsther AtereÎncă nu există evaluări

- HSE Training FeedbackDocument2 paginiHSE Training FeedbackPanchdev KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Competency Assessment 2014 15Document16 paginiCompetency Assessment 2014 15api-309909634Încă nu există evaluări

- Training and Develoment... FinalDocument13 paginiTraining and Develoment... FinalSyed Amad WajidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Calculating ROI For Technology InvestmentsDocument12 paginiCalculating ROI For Technology Investmentsrefvi.hidayat100% (1)

- Engineering BrochureDocument14 paginiEngineering BrochureAditya MahajanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction of The Software Sysdrill by Paradigm: M.Sc. Faissal BoulakhrifDocument66 paginiIntroduction of The Software Sysdrill by Paradigm: M.Sc. Faissal BoulakhrifTyo DekaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carpenter Job DescriptionDocument1 paginăCarpenter Job DescriptionΣπίθας ΣπιθαμήÎncă nu există evaluări

- BPO MethodologyDocument2 paginiBPO MethodologyriturajuniyalÎncă nu există evaluări

- REGDOC2 1 2 Safety Culture Final EngDocument31 paginiREGDOC2 1 2 Safety Culture Final Engnagatopein6Încă nu există evaluări

- On The Rig Drilling SystemsDocument10 paginiOn The Rig Drilling Systemscippolippo123Încă nu există evaluări

- Airbus Case SolutionDocument3 paginiAirbus Case Solutionfiza GÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategic Maintenance Management 101 PDFDocument76 paginiStrategic Maintenance Management 101 PDFCESARALARCON1Încă nu există evaluări

- Technology Vendor Transition StrategyDocument7 paginiTechnology Vendor Transition StrategyasadnawazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swot Analysis of Go AirDocument2 paginiSwot Analysis of Go Airmangesh_7735100% (1)

- BPO BenchmarkDocument2 paginiBPO BenchmarkShaun DunphyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Depreciation Drilling Rigs Esv2008Document108 paginiDepreciation Drilling Rigs Esv2008corsini999Încă nu există evaluări

- BIW Products Services Brochure 042019 PDFDocument13 paginiBIW Products Services Brochure 042019 PDFJusman Van SitohangÎncă nu există evaluări

- BilcoDocument16 paginiBilcoruloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cougar Drilling SolutionDocument41 paginiCougar Drilling SolutionTanzil100% (1)

- Interview Q/a Raustabout Oil RigDocument2 paginiInterview Q/a Raustabout Oil RigShane India Raza100% (1)

- Recommended Field Running Procedure For EUE-PA ConnectionsDocument3 paginiRecommended Field Running Procedure For EUE-PA ConnectionsHanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Competency Assessment FormDocument2 paginiCompetency Assessment FormLielet MatutinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Questions For Root Cause Analysis Participants (Job Titles)Document4 paginiQuestions For Root Cause Analysis Participants (Job Titles)paul_aldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Turnkey Contract IntroDocument3 paginiTurnkey Contract Introsarathirv6Încă nu există evaluări

- Joint Declaration Under para 26 (6) of The Epf Scheme, 1952Document2 paginiJoint Declaration Under para 26 (6) of The Epf Scheme, 1952prakash reddyÎncă nu există evaluări

- BVM Corporation Maintenance Manual: 4-1/2 - 14" Casing Spider / ElevatorDocument40 paginiBVM Corporation Maintenance Manual: 4-1/2 - 14" Casing Spider / ElevatorAnang SakraniÎncă nu există evaluări

- IADC Incident StatisticsDocument15 paginiIADC Incident StatisticsAnisBelhajAissaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Logframs ExDocument15 pagini1 Logframs ExOutah BernardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Superintendent Description: Key Performance IndicatorsDocument1 paginăSuperintendent Description: Key Performance IndicatorsJoshua Abhishek100% (1)

- Silo Weigh PDFDocument7 paginiSilo Weigh PDFOleg AndrisanÎncă nu există evaluări

- VA VG Service ManualsDocument32 paginiVA VG Service ManualshenotharenasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Safety Alert: Driller Inattention Results in Dropped BlocksDocument1 paginăSafety Alert: Driller Inattention Results in Dropped Blockscase013Încă nu există evaluări

- Slab Gate Valves Api 6ADocument39 paginiSlab Gate Valves Api 6AJuan Pablo100% (1)

- Using A Conformity Matrix To Align Processes To ISO 9001 - 2015Document4 paginiUsing A Conformity Matrix To Align Processes To ISO 9001 - 2015esivaks2000Încă nu există evaluări

- Break Even AnalysisDocument19 paginiBreak Even AnalysisNaveen KrishnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moog ServoValves G761 761series Catalog enDocument19 paginiMoog ServoValves G761 761series Catalog enJavier MiramontesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bid RequisitionDocument21 paginiBid RequisitionHank GilbertÎncă nu există evaluări

- COSL Casing RunningDocument3 paginiCOSL Casing RunninghshobeyriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Awilco Drilling PresentationDocument26 paginiAwilco Drilling PresentationAnonymous Ht0MIJÎncă nu există evaluări

- P 7 - Performance Appraisal System - 13.04.2013Document18 paginiP 7 - Performance Appraisal System - 13.04.2013Ur OojÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ms Project Gnatt ChartDocument1 paginăMs Project Gnatt ChartAnithaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soft Torque Plugin For Precise PsDocument1 paginăSoft Torque Plugin For Precise PsJulio Alejandro Rojas BarbaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DEP Inspection ReportDocument9 paginiDEP Inspection ReportNational Content DeskÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sms Gap Analysis Implementation Planning ToolDocument13 paginiSms Gap Analysis Implementation Planning ToolsmallhausenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intertec ConsultingDocument26 paginiIntertec ConsultingjkmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Back Presure Valve in PCP or SRPDocument15 paginiBack Presure Valve in PCP or SRPShubham GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drill ViewDocument2 paginiDrill ViewJohn Rong100% (1)

- Risk Assessment SIMOPS Drilling Vs Venting AlphaDocument7 paginiRisk Assessment SIMOPS Drilling Vs Venting AlphaLouise TeboÎncă nu există evaluări

- CalemEAM Functionality AjaxDocument8 paginiCalemEAM Functionality Ajaxเกียรติศักดิ์ ภูมิลาÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Project Report ON Wages and Salary Administration & Morale of The Employee IN ONGC LTDDocument89 paginiA Project Report ON Wages and Salary Administration & Morale of The Employee IN ONGC LTDImraan KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contractors Policy and ProceduresDocument8 paginiContractors Policy and Proceduresglenn umaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Expatriate Assignment Versus Overseas ExperienceDocument17 paginiExpatriate Assignment Versus Overseas ExperienceOksana LobanovaÎncă nu există evaluări

- IHRM - Repatriation IssuesDocument16 paginiIHRM - Repatriation IssuesFaiza OmarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 30 BÀI LUẬN MẪU DÀNH CHO HS CẤP 2Document7 pagini30 BÀI LUẬN MẪU DÀNH CHO HS CẤP 2Đào Thị HảiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topic 1 - OposicionesDocument6 paginiTopic 1 - OposicionesCarlos Sánchez GarridoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Form 1 BC-CSCDocument3 paginiForm 1 BC-CSCCarina TanÎncă nu există evaluări

- University of Plymouth: Faculty of Science and EngineeringDocument12 paginiUniversity of Plymouth: Faculty of Science and EngineeringLavish JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading - Writing B1 - Aug 2018Document6 paginiReading - Writing B1 - Aug 2018Nguyen Hoang NguyenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theories of Media RepresentationDocument20 paginiTheories of Media RepresentationFilozotaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human Resource DevelopmentDocument150 paginiHuman Resource DevelopmentMeshan Govender100% (1)

- Friends and Family - Called To Peace MinistriesDocument1 paginăFriends and Family - Called To Peace MinistriesMónica Barrero RojasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impulsive ForceDocument4 paginiImpulsive Forcemrs aziziÎncă nu există evaluări

- MORE 1119 Module For Remedial English - KedahDocument191 paginiMORE 1119 Module For Remedial English - KedahsalmirzanÎncă nu există evaluări

- KPMG Interactive ACCADocument8 paginiKPMG Interactive ACCAKapil RampalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Savali Newspaper Issue 27 10th 14th July 2023 MinDocument16 paginiSavali Newspaper Issue 27 10th 14th July 2023 MinvainuuvaalepuÎncă nu există evaluări

- STUDENTS' METACOGNITIVE STRATEGIES, MOTIVATION AND GOAL ORIENTATION: ROLE TO ACADEMIC OUTCOMES IN SCIENCE Authored By: JONATHAN P. CRUZDocument73 paginiSTUDENTS' METACOGNITIVE STRATEGIES, MOTIVATION AND GOAL ORIENTATION: ROLE TO ACADEMIC OUTCOMES IN SCIENCE Authored By: JONATHAN P. CRUZInternational Intellectual Online PublicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Judge Rebukes Aspiring Doctor, Lawyer Dad For Suing Over Med School DenialDocument15 paginiJudge Rebukes Aspiring Doctor, Lawyer Dad For Suing Over Med School DenialTheCanadianPressÎncă nu există evaluări

- Memorandum of Understanding TemplateDocument3 paginiMemorandum of Understanding TemplateMARY ROSE CAGUILLOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Krashen's Input Hypothesis and English Classroom TeachingDocument4 paginiKrashen's Input Hypothesis and English Classroom TeachingNagato PainwareÎncă nu există evaluări

- Romeo and Juliet Summative Assessment RubricsDocument2 paginiRomeo and Juliet Summative Assessment Rubricsapi-502300054Încă nu există evaluări

- HR ProjectDocument49 paginiHR ProjectamanÎncă nu există evaluări

- English 7 DLL Q2 Week 1Document7 paginiEnglish 7 DLL Q2 Week 1Anecito Jr. Neri100% (1)

- La Competencia Fonética y Fonológica. Vocales y DiptongosDocument9 paginiLa Competencia Fonética y Fonológica. Vocales y DiptongosAndreaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SASTRA Deemed To Be UniversityDocument1 paginăSASTRA Deemed To Be UniversityGayathri BÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cbse - Department of Skill Education Curriculum For Session 2021-2022Document15 paginiCbse - Department of Skill Education Curriculum For Session 2021-2022Ashutosh ParwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- My CVDocument2 paginiMy CVMuleta KetelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Techeduhry - Nic.in During Counseling PeriodDocument19 paginiTecheduhry - Nic.in During Counseling Periodsinglaak100% (2)

- 家庭作业奖励Document7 pagini家庭作业奖励ewaefgsvÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Importance of Teacher EthicsDocument3 paginiThe Importance of Teacher EthicsLedina Ysabella M. AchividaÎncă nu există evaluări