Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Roquete - Accuracy of Echogenic Periportal Enlargement in USG - DD Biliary Atresia

Încărcat de

romeoenny4154Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Roquete - Accuracy of Echogenic Periportal Enlargement in USG - DD Biliary Atresia

Încărcat de

romeoenny4154Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

0021-7557/08/84-04/331

Jornal de Pediatria

Copyright 2008 by Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Accuracy of echogenic periportal enlargement image in

ultrasonographic exams and histopathology

in differential diagnosis of biliary atresia

Mariza L. V. Roquete,

1

Alexandre R. Ferreira,

2

Eleonora D. T. Fagundes,

3

Lcia P. F. Castro,

4

Rogrio A. P. Silva,

5

Francisco J. Penna

6

Abstract

Objectives: To define the sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of the ultrasound triangular cord sign and hepatic

histopathology, in isolation or in combination, for diagnostic differentiation between biliary atresia and intrahepatic

cholestasis.

Methods: This was a retrospective study carried out between January 1990 and December 2004. Fifty-one cases

of biliaryatresiaand45of intrahepatic cholestasis wereanalyzed. Histopathologywas performedblindbyapathologist.

The triangular cord sign was identified in ultrasound reports as the only diagnostic sign of biliary atresia. Sensitivity,

specificity and accuracy were calculated for the triangular cord sign and histology both in isolation and in combination.

The gold standard for diagnosis of biliary atresia was the appearance of the extrahepatic biliary tree via laparotomy.

Results: The triangular cord sign alone had sensitivity of 49%, specificity of 100% and accuracy of 72.5%.

Histopathology compatible with extrahepatic biliary obstruction alone had 90.2% sensitivity, 84.6% specificity and

87.8%accuracy. Thetriangular cordsignandhistopathologyinisolationor combinationresultedinsensitivityof 93.2%,

specificity of 85.7% and accuracy of 90.3%.

Conclusions: Finding the triangular cord sign on ultrasound is an indication for laparotomy. If the triangular cord

sign is negative, liver biopsy is indicated; if histopathology reveals signs of biliary atresia, explorative laparotomy is

indicated. In cases where the triangular cord sign is absent and histopathology indicates neonatal hepatitis or other

intrahepatic cholestasis, clinical treatment or observation are recommended in accordance with the diagnosis.

J Pediatr (Rio J). 2008;84(4):331-336: Neonatal cholestasis, biliary atresia, ultrasound, liver biopsy.

Introduction

Neonatal cholestasis syndromeis oneof thegreatest chal-

lenges to pediatric hepatology, due to the countless possible

causes and the need for rapid diagnosis of treatable condi-

tions. Neonatal cholestasis can be classified into two major

subsets, accordingtointrahepatic or extrahepatic causes. The

intrahepatic group includes countless clinical entities of a

metabolic, toxic or infectious nature. In contrast, the extra-

hepatic group - obstructive and surgical - is limited to a small

number of conditions: biliary atresia (BA), choledochal cyst,

bile duct stenosis and bile duct microlithiasis. The apparent

simplicity of this classification of the cholestasis may catch

out clinicians faced with a diagnostic dilemma that demands

rapid and precise resolution.

1

1. Doutora. Professora adjunta, Departamento de Pediatria, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

2. Doutor. Professor adjunto, Departamento de Pediatria, Faculdade de Medicina, UFMG, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

3. Pediatra. Doutora.

4. Professora associada, Departamento de Anatomia Patolgica, Faculdade de Medicina, UFMG, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

5. Mestre, UFMG, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. Mdico, Instituto Alfa de Gastroenterologia, Hospital das Clnicas, UFMG, Belo Horizonte, MG e Centro Especiali-

zado em Ultra-Sonografia (CEU), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

6. Professor titular, Departamento de Pediatria, Faculdade de Medicina, UFMG, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

No conflicts of interest declared concerning the publication of this article.

Suggested citation: Roquete ML, Ferreira AR, Fagundes ED, Castro LP, Silva RA, Penna FJ. Accuracy of echogenic periportal enlargement image in ultra-

sonographic exams and histopathology in differential diagnosis of biliary atresia. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2008;84(4):331-336.

Manuscript received Mar 25 2008, accepted for publication May 28 2008.

doi:10.2223/JPED.1811

331

Biliary atresia is responsible for 45% of cholestatic dis-

eases in children. Prognosis is determined by surgical correc-

tion, using the Kasai procedure (hepatoportoenterostomy),

before 60 days of life.

1

Wheninvestigatinga newbornor infant withjaundice sec-

ondary to conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, abdominal ultra-

sound (US) is one of the tests with greatest diagnostic

relevance. Althoughit is considered operator-dependent, it is

accessible, low-cost, noninvasiveanddoes not dependonliver

function.

1

The lack of specificity for BA diagnosis of classical

ultrasound findings has been replaced by the prospect of

improving diagnostic accuracy based on a newsign visible on

US the triangular cord sign which was first described by

Koreanauthors.

2-5

The triangular cordis a fibrous mass of tri-

angular or tubular shape that is located at the cranial portion

of the bifurcationof the portal veinandwhichis the ultrasono-

graphic manifestation of the fibrous tissue remnant in the

region of the porta hepatis.

2

Notwithstanding, withtheexceptionof explorativelaparo-

tomy which is the gold standard, liver biopsy is considered

the best diagnostic test for BA. If the specimen contains five

to seven portal spaces, accuracy can reach 93%at centers of

excellence with pediatric pathologists trained in hepatology.

6

The objective of this study is to define the sensitivity,

specificity and accuracy of the triangular cord sign (TCS) on

ultrasound and hepatic histopathology, in isolation or in con-

junction, for differential diagnosis between BA and the intra-

hepatic cholestasis.

Methods

Patients

This was a retrospective study carried out at the Pediatric

HepatologyDepartment at theHospital das Clnicas at theUni-

versidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG) in Brazil. The

patient sample was made up of those infants aged less than 6

months who were referred to the department between Janu-

ary of 1990 and December of 2004 for investigation of the

causes of neonatal cholestasis syndrome. Patients who had

undergone US and/or liver biopsy were included in the study.

Infants were excluded if they were more than 6 months old,

had ultrasound diagnoses of choledochal cyst or bile duct

microlithiasis, had incomplete data on their medical records

or their workup had been performed at another institution.

The study sample therefore comprised 96 infants with

neonatal cholestasis. Fifty-one infants had a diagnosis of BA

confirmed by explorative laparotomy combined with intraop-

erative cholangiography where feasible.

Age at the time of ultrasound varied from 6 to 155 days

(mean: 68.632.0; median: 65.5). Liver biopsies were taken

from patients aged from 5 to 155 days (mean: 79.430.6:

median: 75.5).

Abdominal ultrasound

Ultrasound reports were checked for the presence or

absence of TCS. The triangular cord sign, viewed on trans-

verse and longitudinal scans following the portal vein, is seen

on ultrasound as a structure of echogenic density, with thick-

ness 3.0 mm, and a triangular or tubular shape, located at

the bifurcation of the portal vein affecting its first and second

order branches. No other ultrasound findings were taken into

account in this study.

Scans wereperformedbyseveral different ultrasoundspe-

cialists at the Radiology Department of the UFMGHospital das

Clnicas. A range of different systems were used, depending

ondate andcircumstances, with5.0or 7.5MHz linear probes.

Hepatic histopathology

Liver biopsies were taken percutaneously in 52.7% of

cases, using a Hepafix

1.6 needle; the remainder were sur-

gical wedgebiopsies. After beingfixedinformol salineat 10%,

theliver specimenis processedusingroutinehistological tech-

niques, up to setting in paraffin; the paraffin block is sec-

tioned with a microtome and, fromeach block, five slides are

produced of 5.0 to 7.0 m thick histological sections, which

are stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), reticulin, Perls

(Prussian blue), Gomoris or Massons trichrome and periodic

acid-Schiff (PAS) with and without diastase. Slides with less

than five portal spaces were excluded from the analysis.

Histopathological analysis of the liver biopsy slides was

performed blind by a single experienced pathologist fromthe

department.

Definitive diagnosis

Biliary atresia diagnoses were confirmed by explorative

laparotomy by means of macroscopic identification of the

atretic extrahepatic bile ducts and gallbladder and by opera-

tive cholangiography when it was feasible to inject a contrast

medium into the pervious gallbladder. Laparotomy, with or

without cholangiography, was therefore the gold standard for

BA diagnosis, since it is the only procedure that can defini-

tively confirm or rule out a diagnosis of BA.

1,6,7

The surgical

team comprises four pediatric surgeons.

In order to diagnose clinical or intrahepatic cholestasis,

clinical follow-up was required, with remission of jaundice in

up to 3 months of observation and assessment of clinical sta-

tus plus the use of laboratory tests for certaindiagnoses: idio-

pathic neonatal hepatitis, multifactorial cholestasis, Alagille

syndrome, alpha-1-antitrypsindeficiency, tyrosinemia, galac-

tosemia, and others.

Statistics

This is a retrospective study based on analysis of patient

medical records.

Dataanalysis was performedusingthepublic domainsoft-

ware program Epi-Info, version 6.

8

332 Jornal de Pediatria - Vol. 84, No. 4, 2008 Differential diagnosis of biliary atresia - Roquete ML et al. 332

Sensitivity, specificity and accuracy for the diagnosis of

BA were calculated for the TCS and for histopathological find-

ings of extrahepatic biliary obstruction in isolation. The same

parameters were then calculated for two other cases: in the

first case, both the TCS and histopathology compatible with

extrahepatic biliary obstructionwereobligatory for diagnosis;

in the second, diagnosis could be made on the basis of one or

the other being positive.

The study was approved by Research Ethics Committee

at UFMG.

Results

When used as the only criterion for a diagnosis of BA, the

TCS (Figure 1) had sensitivity of 49.0% (95%CI 34.6-63.5)

and specificity of 100% (95%CI 89.6-100); accuracy was

72.5% (95%CI 62.0-81.1). There were, therefore, no

false-positives. Around 50% of cases of BA were, however,

false-negative on US, being wrongly classified as intrahe-

patic cholestasis.

Histopathology findings compatible with extrahepatic

obstruction of BA exhibited sensitivity of 90.2% (95%CI

77.6-96.3), specificityof 84.6%(95%CI 68.8-93.6) andaccu-

racy of 87.8%(95%CI 78.8-93.4) when used as the only cri-

terion for diagnosis. Five of the 51 patients with BA were

false-negative, while six out of 39 intrahepatic cholestasis

patients who had histopathology compatible with BA, i.e.,

were false-positive.

When TCS and histopathology with extrahepatic obstruc-

tion were taken together for diagnosis of BA, sensitivity was

42.2% (95%CI 28.0-57.8) and specificity 100% (95%CI

86.3-100). Diagnostic accuracy was of the order of 65.8%

(95%CI 53.9-76.0).

Wheneither of the two was acceptedas sufficient for diag-

nosis, theresults wereas follows: sensitivityof 93.2%(95%CI

80.3-98.2), specificityof 85.7%(95%CI 66.4-95.3) andaccu-

racy of 90.3% (95%CI 80.4-95.7).

Discussion

This is a retrospective study and as such is subject to the

limitations inherent to this type of design, such as the learn-

ing curve over time and changes related to improvements in

equipment and/or techniques. Data on periportal thickening

were obtained froma reviewof ultrasound reports. The scans

were performed by several different ultrasound specialists

since the patient load at the department is too great for all

scans to be performed by a single professional. It was there-

fore decided to reflect the prevailing reality in including

abdominal US scans that had been carried out by all of the

medical professionals who do US scans at the Radiology

Department of the UFMG Hospital das Clnicas. Despite this,

it was possible to achieve 100% specificity, as shown by the

pilot study by Pinto-Silva et al.,

9

where sensitivity was 62.5%

using a single experienced examiner.

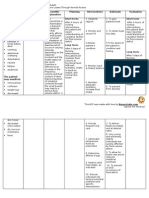

Table 1 is a synthesis of the experiences with ultrasound

of a selection of authors and the results of this study, with

emphasis onTCSfor diagnosis of BA.

4,10-14

Except inthestudy

carried out in Japan, where scans were performed by two

ultrasoundspecialists, all of theothers usedsingleexaminers.

When this study is compared with those from Asia and

Egypt, the sample from the UFMG Hospital das Clnicas is

larger than the others as a result of the 15-year study period,

Figure 1 - Triangular cord sign on first and second order branches

Differential diagnosis of biliary atresia - Roquete ML et al. Jornal de Pediatria - Vol. 84, No. 4, 2008 333 333

which is a longer period than described by the other authors.

The sensitivity of 49.0% found here is equivalent to one half

to two-thirds of the values foundby other studies, makingthe

exam inadequate for screening at our department if used in

isolation. This lowsensitivity can be attributed to the hetero-

geneous nature of the ultrasound specialists levels of expe-

rience at recognizing the TCS image. If, on one hand, the low

sensitivity means that around half of BA cases were not diag-

nosed by US, the 100% specificity means that patients with

intrahepatic cholestasis will not be unnecessarily subjected

toexplorativelaparotomy. TheTCSfindingcanspeeduprefer-

ral for laparotomy, making other diagnostic tests unneces-

sary, especiallyfor patients whoarriveat thedepartment later.

Training the ultrasound team involved with examining chil-

dren could improve the sensitivity of this investigative tech-

nique at identifying TCS.

Twenty-five of the 49 BA cases that underwent ultra-

sound and where TCS was not found would have had their

diagnosis of BAruledout if persistent fecal acholiaandhepatic

histopathology had not also been available during workup.

This demonstrates the need to include histopathology results

in the differential diagnosis of infants with cholestasis.

The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of hepatic histo-

pathologyobservedhereis listedinTable2together withother

teams experiences.

15-21

The last two studies were per-

formed in Brazil. This study was compared with the other two

Brazilian studies in view of the institutional similarities. In

common with our study, both the studies from the state of

So Paulo describe patients treated at public university

hospitals: Gastrocentro at the Medical Sciences Faculty of the

UniversidadeEstadual deCampinas

20

andtheInstitutodaCri-

ana at the Universidade de So Paulo.

21

The sample in our

study was larger because it includes all cases of neonatal

cholestasis over a 15-year period. The neonatal cholestasis

samples in the Campinas and So Paulo studies were from

periods of 4years and6months and6years, respectively.

20,21

Fromthe total of 90 liver biopsies analyzed, based on the

criterion of extrahepatic obstruction compatible with BA, 11

cases were wrongly diagnosed. There were six false-positives

and five false-negatives. In view of the low sensitivity of US,

it was combined withhepatic histopathology to improve diag-

nostic performance.

There was a discrete improvement over histopathology in

isolation when either of the two diagnostic criteria was

accepted for diagnosis. Sensitivity rose from 90.2 to 93.2%,

specificity from 84.6 to 85.7%, and accuracy from 87.8 to

90.3%.

The only definitive diagnostic test for BAremains, to date,

explorative laparotomy, whether diagnosis is based on an

atretic gallbladder seen macroscopically, replaced by fibrous

remnants, or by intraoperative cholangiography.

7,22

Never-

theless, less invasive preliminary tests capable of refining the

indications for laparotomy are necessary to avoid unneces-

sarily subjecting patients with cholestasis due to intrahepatic

causes to the procedure.

The lowsensitivity of ultrasound means that combining it

withliver biopsy results is indispensable toobtainingdiagnos-

tic confidence with relation to BA and, as a result, to safely

indicating laparotomy for children with neonatal cholestasis.

The merit of the TCS ultrasound sign lies in its 100%specific-

ity, which can be of aid in speeding up referral for laparotomy,

especially where infants arrive at the department aged more

than60days. All of the cases that exhibitedthe signwere con-

firmed as BA. Due to the improved diagnostic performance

offered by combining hepatic histopathology with the TCS, it

is recommended that TCS and histopathology be combined

for faster, more reliable, diagnoses.

Table 1 - Comparison between different authors findings for sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of triangular cord sign for diagnosis of BA

Authors Country n Sensitivity (%) Specificity (%) Accuracy (%)

Park et al., 1997

4

Korea 61 85.0 100.0 95.0

Kendrick et al., 2000

10

Singapore 60 83.3 100.0 96.7

Kotb et al., 2001

11

Egypt 60 100.0 100.0 100.0

Lee et al., 2003

12

Korea 86 80.0 98.0 94.0

Visrutaratna et al., 2003

13

Thailand 46 95.7 73.9 84.8

Kanegawa et al., 2003

14

Japan 55 93.0 96.0 95.0

Roquete et al. Brazil 91 49.0 100.0 72.5

BA = biliary atresia.

334 Jornal de Pediatria - Vol. 84, No. 4, 2008 Differential diagnosis of biliary atresia - Roquete ML et al. 334

The results of this study agree with the algorithm pro-

posed by Kotb et al.:

11

the TCS sign seen on ultrasound is

enoughto indicate laparotomy withcholangiography, if this is

feasible. If the TCSis negative, liver biopsy is indicated; if his-

topathologyshows signs of BA, explorativelaparotomyis once

more indicated. In cases where TCS is negative and histopa-

thology indicates neonatal hepatitis or other intrahepatic

cholestasis, clinical treatment or observation are recom-

mended in accordance with the diagnosis.

References

1. Bernard O. Cholestatic childhood liver diseases. Acta

Gastroenterol Belg. 1999;62:295-9.

2. Choi SO, Park WH, Lee HJ, Woo SK. Triangular cord: a

sonographic finding applicable in the diagnosis of biliary atresia.

J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:363-6.

3. Choi SO, Park WH, Lee HJ. Ultrasonographic triangular cord:

the most definitive finding for noninvasive diagnosis of

extrahepatic biliary atresia. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1998;8:12-6.

4. Park WH, Choi SO, Lee HJ, Kim SP, Zeon SK, Lee SL. A new

diagnostic approach to biliary atresia with emphasis on the

ultrasonographic triangular cord sign: comparison of

ultrasonography, hepatobiliary scintigraphy, and liver needle

biopsy in the evaluation of infantile cholestasis. J Pediatr Surg.

1997;32:1555-9.

5. Park WH, Choi SO, Lee HJ. Theultrasonographic triangular cord

coupled with gallbladder images in the diagnosis prediction of

biliary atresia from infantile intrahepatic cholestasis. J Pediatr

Surg. 1999;34:1706-10.

6. Schreiber RA, Kleinman RE. Biliary atresia. J Pediatr

Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35 Suppl 1:S11-6.

7. Middlesworth W, Altman RP. Biliary atresia. Curr Opin Pediatr.

1997;9:265-9.

8. Dean AG, Dean JA, Culombier D. Epi Info, version 6; a word

processing, database, and statistics program for epidemiology

onmicrocomputers. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and

Prevention; 1994.

9. Pinto-Silva RA, Roquete ML, Ferreira AR, Penna FJ, Lobo BM,

Silveira JL, et al. Espessamento ecognico periportal: achado

ultra-sonogrfico sugestivo de AB extra-heptica. Acta Radiol

Paulista. 1998;1:49-53.

10. Tan Kendrick AP, Phua KB, Ooi BC, Subramaniam R, Tan CE,

Goh AS. Making the diagnosis of biliary atresia using the

triangular cordsignandgallbladder length. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;

30:69-73.

11. Kotb MA, Kotb A, Sheba MF, El Koofy NM, El-Karaksy HM,

Abdel-Kahlik MK, et al. Evaluation of the triangular cord sign in

the diagnosis of biliary atresia. Pediatrics. 2001;108:416-20.

12. Lee HJ, Lee SM, Park WH, Choi SO. Objective criteria of

triangular cord sign in biliary atresia on US scans. Radiology.

2003;229:395-400.

13. Visrutaratna P, Wongsawasdi L, Lerttumnongtum P,

Singhavejsakul J, Kattipattanapong V, Ukarapol N. Triangular

cordsignandultrasoundfeatures of thegall bladder intheinfants

with biliary atresia. Australas Radiol. 2003;47:252-6.

14. Kanegawa K, Akasaka Y, Kitamura E, Nishiyama S, Muraji T,

Nishijima E, et al. Sonographic diagnosis of biliary atresia in

pediatric patients using the triangular cord sign versus

gallbladder length and contraction. AJR AmJ Roentgenol. 2003;

181:1387-90.

15. Manolaki AG, Larcher VF, Mowat AP, Barrett JJ, Portmann B,

Howard ER. The prelaparotomy diagnosis of extrahepatic biliary

atresia. Arch Dis Child. 1983;58:591-4.

16. Tolia V, Dubois RS, Kagalwalla A, Fleming S, Dua V. Comparison

of radionuclear scintigraphy and liver biopsy in the evaluation of

neonatal cholestasis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986;5:

30-4.

17. Faweya AG, Akinyinka OO, Sodeinde O. Duodenal intubationand

aspiration test: utility in the differential diagnosis of infantile

cholestasis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;13:290-2.

18. Sanz CR, Castilla EN. Papel de la biopsia heptica en el

diagnsticode la colestasis prolongada emlactentes. Rev Invest

Clin. 1992;44:193-202.

Table 2 - Comparison between different authors results for sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of hepatic histopathology for diagnosing BA

Source n Sensitivity (%) Specificity (%) Accuracy (%)

Manolaki et al., 1983

15

86 90.0 82.5 86.5

Tolia et al., 1986

16

24 95.6 90.0 93.9

Faweya et al., 1991

17

27 83.3 100.0 92.6

Sanz & Castilla, 1992

18

78 89.0 95.5 93.0

Lai et al., 1994

19

121 92.9 97.6 96.8

Hessel et al., 1994

20

35 76.0 94.0 86.0

Zerbini et al., 1997

21

74 100.0 75.9 90.5

Roquete et al. 90 90.2 84.6 87.8

BA = biliary atresia.

Differential diagnosis of biliary atresia - Roquete ML et al. Jornal de Pediatria - Vol. 84, No. 4, 2008 335 335

19. Lai MW, Chang MH, Hsu SC, Hsu HC, Su CT, Kao CL, et al.

Differential diagnosisof extrahepaticbiliaryatresiafromneonatal

hepatitis: aprospectivestudy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994;

18:121-7.

20. Hessel G, Yamada RM, Escanhoela CA, Bustorff-Silva JM,

Toledo RJ. Valor da ultra-sonografia abdominal e da biopsia

heptica percutnea no diagnstico diferencial da colestase

neonatal. Arq Gastroenterol. 1994;31:75-82.

21. Zerbini MC, Galluci SD, Maezono R, Ueno CM, Porta G,

Maksoud JG, et al. Liver biopsy in neonatal cholestasis: a review

on statistical grounds. Mod Pathol. 1997;10:793-9.

22. de Carvalho E, Ivantes CA, Bezerra JA. Extrahepatic biliary

atresia: current concepts and future directions. J Pediatr (Rio J).

2007;83:105-20.

Correspondence:

Mariza L. V. Roquete

Rua Professor Norton Kaiserman, 82/102 - Anchieta

CEP 30310-570 - Belo Horizonte, MG - Brazil

E-mail: roquetemlv@uol.com.br

336 Jornal de Pediatria - Vol. 84, No. 4, 2008 Differential diagnosis of biliary atresia - Roquete ML et al. 336

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Dizziness in PaedDocument7 paginiDizziness in Paedromeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- List of Allergens: Skin Prick Test Allergens 01/29/2016Document3 paginiList of Allergens: Skin Prick Test Allergens 01/29/2016romeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- 51 Allergens Set: Sr. No. Patch Test Allergen Price (RS.)Document2 pagini51 Allergens Set: Sr. No. Patch Test Allergen Price (RS.)romeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Contoh ReviewDocument6 paginiContoh Reviewromeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- PolyarthritisDocument6 paginiPolyarthritisromeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Ulceration Slides 090331Document62 paginiUlceration Slides 090331mumutdwsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pneumonia and Respiratory Tract Infections in ChildrenDocument37 paginiPneumonia and Respiratory Tract Infections in ChildrenjayasiinputÎncă nu există evaluări

- Children Perio DiseasesDocument9 paginiChildren Perio Diseasesdr parveen bathlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Afebrile SeizuresDocument11 paginiAfebrile SeizuresMai Hunny100% (1)

- HemophiliaDocument2 paginiHemophiliaromeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Reasoning Handout: URI Symptoms Sore Throat 1) Pearls BackgroundDocument5 paginiClinical Reasoning Handout: URI Symptoms Sore Throat 1) Pearls Backgroundromeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Febrile Seizure GuidelineDocument1 paginăFebrile Seizure GuidelinesmileyginaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DD Viral ExantemDocument4 paginiDD Viral Exantemsiska_mariannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute Fever in Children and InfantDocument26 paginiAcute Fever in Children and Infantromeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Febrile Neonate Clinical Practice Guideline: CatheterizedDocument1 paginăFebrile Neonate Clinical Practice Guideline: Catheterizedromeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Common Anemia in Pediatric BRM - PM - V1P4 - 03Document12 paginiCommon Anemia in Pediatric BRM - PM - V1P4 - 03romeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Congenital Heart Disease 2014Document1 paginăCongenital Heart Disease 2014romeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Acute Stridor Diagnostic Challenges in Different Age Groups Presented To The Emergency Department 2165 7548.1000125Document4 paginiAcute Stridor Diagnostic Challenges in Different Age Groups Presented To The Emergency Department 2165 7548.1000125romeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Bronchiolitis Clinical Guideline2014Document2 paginiBronchiolitis Clinical Guideline2014romeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Guidelines Clinical Management Chikungunya WHODocument26 paginiGuidelines Clinical Management Chikungunya WHOFábio CantonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Approach To Acute Arthritis in Kids: Allyson Mcdonough, MD Baylor Scott & White Health Department of RheumatologyDocument35 paginiApproach To Acute Arthritis in Kids: Allyson Mcdonough, MD Baylor Scott & White Health Department of Rheumatologyromeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Calvin K.W. Tong Approach To A Child With A Cough: General PresentationDocument5 paginiCalvin K.W. Tong Approach To A Child With A Cough: General Presentationromeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Common Anemia in Pediatric BRM - PM - V1P4 - 03Document12 paginiCommon Anemia in Pediatric BRM - PM - V1P4 - 03romeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- GinggivostomatitisDocument6 paginiGinggivostomatitisromeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Croup GuidelineDocument17 paginiCroup Guidelineromeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Adhd Scoring ParentDocument3 paginiAdhd Scoring Parentromeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Reasoning Handout: URI Symptoms Sore Throat 1) Pearls BackgroundDocument5 paginiClinical Reasoning Handout: URI Symptoms Sore Throat 1) Pearls Backgroundromeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- Common Anemia in Pediatric BRM - PM - V1P4 - 03Document12 paginiCommon Anemia in Pediatric BRM - PM - V1P4 - 03romeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- DD Viral ExantemDocument4 paginiDD Viral Exantemsiska_mariannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asthma ED Clinical Guideline2014Document5 paginiAsthma ED Clinical Guideline2014romeoenny4154Încă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- University of Northern Philippines: WWW - Unp.edu - PH CP# 09177148749, 09175785986Document23 paginiUniversity of Northern Philippines: WWW - Unp.edu - PH CP# 09177148749, 09175785986Hanna La MadridÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk Factors Leading To Peptic Ulcer Disease SysteDocument8 paginiRisk Factors Leading To Peptic Ulcer Disease SysteHidayah NurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deficient Fluid Volume (AGEDocument2 paginiDeficient Fluid Volume (AGENursesLabs.com83% (6)

- Cholel FinalDocument39 paginiCholel FinalRizza DaleÎncă nu există evaluări

- HomeWork-Routes of Drug AdministrationDocument2 paginiHomeWork-Routes of Drug AdministrationIrina DogoterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Investigation and Treatment of Surgical JaundiceDocument38 paginiInvestigation and Treatment of Surgical JaundiceUjas PatelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseDocument412 paginiInflammatory Bowel DiseaseSabbra CadabraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Care of A Client With GastritisDocument11 paginiCare of A Client With GastritisFranklin GodshandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Infectious Diseases Affecting The GitDocument64 paginiInfectious Diseases Affecting The GitGeraldine MaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Activity 2 - Body OrientationDocument8 paginiActivity 2 - Body OrientationEuniece AnicocheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interventional Approaches Gallbladder DiseaseDocument9 paginiInterventional Approaches Gallbladder DiseaseAntônio GoulartÎncă nu există evaluări

- Epidemiology, Clinical Characteristics, and Treatment of Children With Acute Intussusception: A Case SeriesDocument6 paginiEpidemiology, Clinical Characteristics, and Treatment of Children With Acute Intussusception: A Case SeriesIqbal RifaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- SucralfateDocument1 paginăSucralfateKatrina Ponce100% (1)

- PLASILDocument2 paginiPLASILmilesmin100% (1)

- ACG Clinical Guideline Ulcerative Colitis In.10Document30 paginiACG Clinical Guideline Ulcerative Colitis In.10Artist Artist0% (1)

- Comprehensive 22-32 EngDocument160 paginiComprehensive 22-32 EngIsna AzizahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report On AmoebiasisDocument36 paginiReport On Amoebiasisrhimineecat71Încă nu există evaluări

- Storage For FecesDocument11 paginiStorage For Fecesحيدر الشمسÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gasteroenterology 201 247Document28 paginiGasteroenterology 201 247Ahmed Kh. Abu WardaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anorectal Suppuration 9.7.11!1!1Document50 paginiAnorectal Suppuration 9.7.11!1!1Shantu Shirurmath100% (2)

- Gerd 2Document12 paginiGerd 2Adeh VerawatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseDocument59 paginiInflammatory Bowel DiseaseLala Rahma Qodriyan SofiakmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drug StudyyyDocument4 paginiDrug StudyyyDanielle OnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revision-Notes Balanced Diet, Malnutrition, Digestion Final 2020Document10 paginiRevision-Notes Balanced Diet, Malnutrition, Digestion Final 2020Oume Hani DookhunÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gastrostomy FeedingDocument8 paginiGastrostomy FeedingToka HessenÎncă nu există evaluări

- ? Emergency Surgery Step-1 MCQ FinalDocument50 pagini? Emergency Surgery Step-1 MCQ Finalp69b24hy8pÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fecal Occult Blood - Hema Screen™: I. PurposeDocument4 paginiFecal Occult Blood - Hema Screen™: I. PurposeEarl Jayve Magno GoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agenda MU Blue Medan 5-7 MayDocument1 paginăAgenda MU Blue Medan 5-7 MayasepyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cholecystectomy (Removal of The Gall Bladder)Document6 paginiCholecystectomy (Removal of The Gall Bladder)Akash ShillÎncă nu există evaluări

- ConstipationDocument7 paginiConstipationDurgaÎncă nu există evaluări