Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Crime in Road Freight Transport

Încărcat de

Marijan JakovljevicDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Crime in Road Freight Transport

Încărcat de

Marijan JakovljevicDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

7

t-

z

w

EUROPEAN CO .FERENCE

OF MI NISTERS OF TRANSPORT

I

MateriJal zasticen autorskim pravom

EUROPEAN CONFERENCE OF MINISTERS OF TRANSPORT fECM'T)

The Eutopean Conference of Ministers of Transport {ECMT) is an inter-governmental organisation

established by a P:rotocof signed in Brussels on 17 October 1953. It i s a forum in which Mi nisters

responsible for t ransport, and more spedfkally the inlal"'d transport sector, can co-operate on policy.

Within thi s forum, Ministers can openl y discu:ss cu.rrent problems and agree upon joint approaches aimed

at improving the utilisation and at ensuri ng t he rational development of European t ransport systems

of i nternational i mportance.

At present. the .ECMT's role primarily consi sts of:

- helping to create an transport System throughout the enlarged Europe that is economically

and technicall y efficient. meets the highest :possible safety and environmental st andards and

takes full account of the Scial di mensi on;

- helping also to build a bridge between the European Union and the rest of the conti nent at a

political level

The Council of the Conference comprises the Ministers of Transport ol 41 full Member countries:

AJbanJa, Austria, Azerbaijan. Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia--Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, rhe Czech Republic.

Denmark, Estonia. Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, ' Finland, France, FYR Macedonia, Georgia, Germany,

Creocc, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Moldova,

Netherl ands, Norway, Poland, Portugal Romani a, the Russian Federation. the Slovak .Republic,

Slovenia, Spain, Swed en, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukrai ne and the United Kingdom. Them are six Associate

member countries (Australia. Canada. Japan, New Zeal and, Republic of Korea and the Uni ted States)

and two Observer countries {AI'menia and Moroc.co) .

A Committee of Deputies, composed of senior dvil servants repl"esendng Minis-ters. prepares

proposals for conslderati on b) the Council of MJnlsters. The Committee is assisted by workJng groups,

each of whkh has a specific mandate.

The issues currently being srudied - on which policy decisions by Mi nisters will he required -

Include the deveJopment and implement.atlon of a pan-.Europe.an policy; the integration of

Central and Eastern European Countries i nto t he European transport market; spedfk issues telating to

transport by rail. road and \vaternay: combined transport. transport and the environment; sustalnable

urban travel; the social costs of t ransport; trends in intemational transport and inlrastructure needs;

transport fur people wlth mobHity handicaps; road safety; traffic management; road trtJ1fk i nformation and

new communi cations technologies.

Stati stical analyses of trends in t.ra.tfic and investment are published regularl y by the ECMT and

provide a clear indication of the situation, -on a tr:imestriaJ or annual basis, in the transpmt sector i n

different urope9n countries.

As part of i ts tesearch activities, the ECMT holds regul ar Sympsia, Semjnars and Round on

transport economics issues. Their condusions serve as a basi s for formul ating: proposals for policy

decisions to be submitted to Mi nisters.

The ECMT's Documentation Service has extensive information avaHable concemi ng the transport

sector. Thls i nformation is accessible on the ECMT Internet sit e.

F'or administrative pumoses the ECMT's Secretariat is attached to the Organisation for Ecoflomic

and Development (OECD}.

Pu&JJi t!ll sous l11 iitn :

La delinquan<.e et la fratldf: dans les transporf:S de marcbandlses

FurJfrer itJJomualhm ;t6out tffe I:.CM.T i> on Lnfenh?l at tfle fcllowing oddrm:

WINI!. IICJClitor g/'tem

0 ECMT 2002 - ECMT Pu&licaUDns are. by: OECO PJdilit.a!lons Serv.ke,

2. rue Andre Pascal , 15-775 PARIS CEO EX 16, France.

MateriJal zasticen autorskim pravom

FOREWORD

Transport related crime is a serious and growing problem. The BCMT Counci l of Ministers'

meetings iu Bedin in: 1997 and in Warsaw in 1999 discus ed the problem and agreed specific

Recommendations on combating it These are included in this publication.

To follow np these recommendations a multidiscipli.oary Steering Group on Combating Crime in

Transport. consisting o.f representatives from different backgrounds of TransJxnt,

Economics and Interior, International organi at1ons- EU. UN/ECE, EUROPOL. INTERPOl-, police,

cos toms, insura.nce, in.dustzy, transport opeicttOt'S etc.) was set up in aumrru1 t 999 to make proposals on

how ECMT can contri bute to combating transpo11 crime, to suggest pri.orities for EO.ifT work and to

guide particular project that are to be undertaken.

Two inm1ediate prioritie \vere identified. Pirst to obtain and make available cornparable

infonnation on transpoJt ctime and second to e amine how devices and conununication

systen1s can be introduced.

This publication swnmarises the work done so far on these topics and contains t he conclusion

adopted by ECJVIT Mini ' ters in 2001.

11te events of September l l'b 2001 have added a new dimension to this subject and undoubtedly,

improving seCUJity in transport: will need to be a feature of ECMT activities in the fuwre.

ECMT gr-d.tefully acknowledges the work of the Steering Group on Combating Crime in

Transport in preparing this report. In particular tha,nk.s are due to Jl\is. Blai ne Hardy for her work in

Part f on the Theft of Goods and Goods Vehicles) and to Mr. FTank Heinrich-Jones (Preventive Anti-

Theft Dtw.ices fnr Road Freight Vehicles), Mr. Jean-Pierre Pascha l (After-Theft Systems) and

tvtr. Dietbe1t K.ollbacb (Shott Range Vehicle ldentitica.tion System) for their contributions to Part II of

the publication.

@ ECMT. 2002

3

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FOREWORD ... . t s 0 o c .. .. I 0 t 1

1 '

s n 0 0 I 0

t 0 0 I

. , . . o r e I 0 ,

0 , . . S I ... . . , o t ft 0 I , ,

.... 0 , . , 0 . s . . . . ... . 3

PART L THEFT OF GOODS AND GOODS VEHICLES ............................ ..... .................... 9

I SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ' ' , , .... . .. . .... . .. . .. ..... . .. . 1 I

Recommendations ... . ,

. . . ... .. ... ... . . . . .... . .. . . , , .. . . . . . . . . . . ... . . . , . . . .. . . .... . . 12

2. FRAMEWORK

' ' 0 ft a ft o t 0 t 0 e n . . d ' 0 0 . . . ... . . . .. .. . 0 . . . . . ..... . . . ... .. . , . . f 0 0 I 0 ft 13

2 1 Scope t t 13

2.2 Ob ec.ti ve ................ .. .. .. ....... .............. .................... ...... 0 0 ............ . ................ 0 0 0 . . .... . . . ...... 0 13

2.3 Background .................................... 0 . ..... . .. . ..... . . ........ ....... ..... ...... . .......... . ....... ....... . .. ... .... . 13

2.4 Methodolo ............ ... .. ... ... ........ , . .. ... ........ ......................... .. ... .... ...... .... 15

2.5 Summ of the Interim Re ort .. ............... ........................ ... .. .. ...... ................................................... .. 16

2.6 16

2.7 llSt! .............................. .............. ......................... ..... .. ............ , .... ............................. . . 18

3. A COMPARATfYE ANALYSIS OF METHODOLOGF.S IN EIIROPE. . ' . . ' 0 0 ...... 20

3. 1 Dcfi nitions .... ....... ..... .. ........ ..... . .. 1 t *1 0 0 t OoOOo ooo oo 1 . . 0 "1 0 . . . 0 .. 0 . . t. 0

oOo

20

3.2 Methods of recordin ~ ~ r ~ ~ ~ 20

3.3 I Dcation 0 0 t ...... . ' 0 * . . . .... 0 t

o o O"ftfto ft o' ot ft "oo ooo*ft "rt ooO tn . 00

27

3.4. Mode of theft ..

0

e 1 t 'tft ft I

0 1' +'

29

3.5 Conclusions ....

-

' . ,, . , d . . .

. . . .. ..... . , .. -;

30

4. COIJNTRY PROFH.ES

. ' . I ft t " "" ft I 1ft . 33

Introduction ... . . . 0 . ' . ' ' 1 ' ! 5 . ' ... . ' 0 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . t I . ' ' 0 .. ' .. ' ! 5 . ' . . . . . ' . ' ... . . 33

4. 1 At1stria ., .. . ..... .. .. ..... .. , .... . ' ' 1 . . . . . .. . . . . .. ..... . . ....... .... . . , ... . . . ..... . 2 ' . ' .. 2 . . . ' . , ... '

. .............. , 33

4 .2

Belgitim .. o . . .. o . . 1 oo o

0

0

0

- o o

0

o

34

4.3 Czoch Re llhlic ................... ................................................ ............................ ...... ............ ......... ....... . 36

4.4 Denmark .. ............. ........... ..... .............

I t ft I I t f f . I

. '

I

37

4.5 Estonia, ................. ....... .. ... . f I I . I I ' I a t t a I I! t , ... ..... .......... . . .... ... ...... I f If . A t tj. I . ....... ... I f I ft. t . t t f ! . .. ... , 39

4.6 Finland .. '0 0 I . . . . t 0 ' .. 0 0 , 0 " ft " I

0 0 0 " ft " I 0 I ' 0 0 . . . t

'.

0 ... I 0 0 ' 0 I 1 0' " I 41

4.7 France ... . . . Itt' ft o t " "I I " t t I*" o tt o t 1 I ft ...... ... . .. t 1 ft t 1 o t t I .. lldftlft "" I ft ft ft .... ........ . ........ .. , . . ... ftldllt 43

4.8 Germany .......... ....... , ..... , ... ,.,, ...... .. . . . . .

2 . , ........ . . .. t ft $ t " I 1 $ I . ..... . . . . f 0 1 I .. . . .. . . . . . . . .

' "ft 0 I I . . , .... 44

4 .9 Greec.e ......... 0 0 0 0

or o

. . 1 0 1 0 0

o o = o

46

4.10 Hungary .. ............ ....................... .. ... ................. ... ... .. ....... ................................ ......... ..... 48

4.11 Ireland ~ .. ... I I .......... .. . ... . ... . . . ...... I .... , w I ........ . . ... I I I I I , I I ~ 49

4.12 llaly ...... . .... . .. . .

0 0 0 0 I t .. .. .. ' I I ""

0 , 0 .... 0 .... 0 .. .... . . 0 I I 0 1 Itt ft 0 0 0 50

4. 13 I Al xembourg .. '"I I I I " 0 I I t I

0 I ' I .. 0 0 I 1 I I " I I " 0 1 o 0 I ' " I I I 0 0 .. I 0 1 o I 0 " I 0 ' I 1 0 1 I t I " 0 1 I I 0' I Sl

4. 14 Netherlands .... ... .......... .. ...... ........ .. ...... ..

..

10 0 1

ft I I I 11 1 t 53

4 . 15 Nornra..y .. ,., ., ..... 0 , . 0 , , , 0

o

0

0 0

t ' 2 2 , 2 . ' 2 56

4. 16 Poland 1 1rt I 1 e .. 0 ..

... 0. 00 00 o

. . . ... o.ooo . .

ooo o =o

57

@ ECMT, 2002

5

MatenJal zastrcen autorskrm pravom

4. 17 Ra1ssja ..... .. .......... ...... ........... ............ .......... .................. . . t 0 0 . .. . . . 0 t , t 0 0 t . . . ... 58

4J8 S ain

~ ~ ~

60

4.19 Sweden ........... ....... .. .. . .. . . . . .. 1 * 0 0 t . . t * . . . . .... e r . .... ... .. . ... .. ' . .. * . . r e . . . 61

4.20 Tit rkey ...... ............ .. ... .. .... ............ ......... .. I. ft ft ft ft ft ft t ft f C ft ft ft ft . .

. . . . . . . .. . . . . . . ..

0 62

4.21 l Jnited Kingdom ....... ...... .. .. , ............... ...... ... ..... .........

e I .... ... 63

Conclus ion . 0 I . I 0 ' . I f I I I I 53 ' ? I 3 0 I . . 68

5. STATISTICAL ANAl .YSIS AND OVIERVJEW

69

5. 1 lnt mdJmctjon .... ... ,, ..... ...... ....... ...... .. ,, .... ...... . . . . .... . ... . .... . , ........ 0. ' . '' 2 ' * * ' '' * '' fep' t I t,

5.2

s . . d . . d

tatt sttcs an 1 net ences ....... .... .. ........ .................. ... .. .... ..... ........ .......... ... ...... .... ........

5.3 Value of vehicles and trailers stolen .. .. .... , . . . . . . . .. . .... .. . . ..... . t I

5.4 Value and incidences of theft of oods from or with vehicles ....... ............................. . .

5.5 Value of oods stolen with or from commercial vehicles .................... ................. .. .. .. ..

,5:...: c:: 6::..._ __ T.=...., Yu: of oods stolen from or with vehicles .............. ............................................ ....... .

5.7 Value of QOods stolen - a case stud of 13 com

arues ... ..

.......... .... .... .... ~

69

70

76

78

79

81

84

6. CONCI .USIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

*

87

6. 1 Conclusions ............ .. 0 e t ft t I 0 . .. . . . . . . . . ... .. .. . ..... n t t I , I ft I 0

f I ........... ...... . ' t 1 87

6.2 Reoommendations , ........ ..... ,. __ ......... ..... , ..... ........ , ...... .. , ......... ____ .. ....... ..... ..... .... + .. . .... . . 88

Annex l. Omanisations Contacted .......... ............................ .... ................... .. ....... ..................................... 90

Annex. 2. Data Collection and Co-o rntion ... .................... ....................... ................... .......... ..... ... 91

B WLIOGRAPHY .. !1 1 81111 .... . . , II .,,, , ,,,., ,,,,, ,,.1., . , 1ft! II ' ..... , .. .. .. ,,,, ..... ,.,,,., .. ,,,.,,,.,, . ,,,., .. ,.,,,, 92

Partll IMPROVING SECT JRITY FOR ROAD FREIGHT VEHICLES . ........ ................. 93

I SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS u .. .. .. , .d' .. .......... .. . . 95

Recommendations to trans rt authorities ...... 95

Rc uests to other authorities and actors ........ .. 96

2. INTRODIJCTION . . t . , , t , . .. , .. .

le o . ., , . , . , . 1 ' ' 1 p 1 96

3. NATJJRE OF THE PROBLEM Pf f ' e p ' $ * ' * $ ' ' $ '' tle t If ' ' p p ' ' f ' 'PAM!$ ' f f ' P 'ft ' t to pee+ t ' t' M PI $ ' $P ' 4*+P $ ft' t P M ' $ 97

4. LEGALRE UIREMENTS, OUIDELJNES A D STANDARDS .. ... .. .......... .. .......... .. ........ 98

4.]

Regulations for securit devices ............... ... .......... ............... . ...................... ......... It !I I II! t t t! !! II 98

Euro n standardisation for after-theft devi ces .....

4.4 National uidelines .......................................................... ................................ ..... ...... .................... 10 I

5. PREVENTIVE ANTJ-THEFf DEVICES .....

0

e M p I 102

Ami theft devices o . o 1 t e 1M o t . . . tooo t t " l '' 1 1 o l " t ' t 1 o e

o

t o n o t t ' l o tt o 102

6. AEI'ER-THEEf SYSTEMS 106

6.1 Two rations .............................. .... .......................... ................... ... ... .................. ............. . 106

6.2 Short ran stems

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

106

6.3 U>n ranae s steJl'lS ................................................................................................... ..... . 107

6.4 After-theft s stems articu1arities ........ ........... ........ .. ...................... ............................. ....... ... . 108

6.5 F

. 'd .

'.CODOIDIC CODSl eratlOUS ........ , ......... ..... ... .. , 1 t I 1 , tl * '' ' of iD ' t t tf l ' ll . . . . I . tt . , . ,

$ I ' Mt tl * ' ' ' tt 109

6

ECMT. 2002

MatenJal zastrcen autorskrm pravom

7. IMPLEMENTATION ISSUES, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ........... 109

7. 1 General conclusions .. , .......... ,., .. ......... ............ ... , .. ,, .. ....... ... .. .... ... .......... ..... , ............... . 109

7.2 The role of trans rt authorities and ministries 110

7.3 Ro le of other actors.. 0 , M 2 t t t t 0 ' t $ t ' t t ' ' . 2 t 1 1 2

Annex l. Vehicle IdentificationS stems ................................................................................. 115

Annex 2 .. GJossatV .... .... .. .... ........ ...................... 4 ........ .. . ........... . ... .. .. ..... ... ....... .. .. ........... .......... . ...... . .... 120

BIBUOGRAPHY I I I I I 4 4 I I $ I I I I I I I t I I I I I &4 I I I I 4! I ! A I .. I I I. 4! t 6 I I II t A I I I I t I I I I I ' I ! I I I 4 I 4 I 4 I ! f I I A I f i I I 4 I ! I f f t I I 4 I t II ! t I I f I e 8 f I I 4 A I! If 121

Part UL OTHER Sl rBJECTS., .. ,., ........ ............... ................................................................... 1 23

I. ILLEGAL IMMIGRATION .. . .. .. ...... ... ...... ... .... ..... ...... ... ............. ... ..... ... .. .... , . . 125

2. FRAUD lN TRANSIT SYSTEMS

126

2.1 s stem TJR .......... ................... ................................. ........... .. ....... .. .................................... ........... .. 126

2.2 Communit /Common Transit .. ... ............... .......... ....... .. ......... ....... ........ ..... ..... ..... ......... ........ ..... . 127

2.3 Conclusions . 0 0 0 0 0 I I 0 7 I I I I - 2 I I I I - I " 0 '1 oo l o l- " 0 '1- 11053 1 - " 11 '"11 ' 53 - 0 ''''' 11 1'- ' 0 17 0 ''- 1 ' 2 1111 128

Part IV. MINISTERIAl. CONCLUSIONS ...................................... ?' 129

Resolution No. 1999/3 on Crime in Trans n ................................................................................... 132

Resolution no. 1997/2 on Crime in International Transporr.. .................................................... 135

@ ECMT, 2002

7

MatenJal zastrcen autorskrm pravom

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Pan ~

THEFT OF GOODS AND GOODS VEIDCLES

@ PJCMT. 2002

9

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

1. SUl'VIMARY OF CONCIJUSIONS AND :RECOMM,ENDATIONS

The objective was to examine available information on goods vehicle crime in Europe and if

possible to suggest bow data and metbodologjes could be improved.

J.nitia.t oontacts were made through the Tnmsport Mhtist.ries which led to queries being directed to

othe.r Ministries, including the Iuterior. 111e bulk of the available data is kept by police authorities m

statistics depa.1.tments within the .Ministries of interior. 'Ibis report contains data fr01n 23 countries.

The rep'Ort describes the med1odologies used in Europe and demonstrates that there i no simple

way to provide <t clear picture of the extent and nah.u-e of the theft of goods and cru.nrtlerd<1l vehicles in

Europe. This is because:

Historical and legal practices and codes vary bet\\'een countries and thus the defuutions of

theft and the i nformation collected on the preci e occmrettce/timing of the Clime differ and

are not comparable.

Each comm:y has a unique system for gatheli.ng ittformation about vehicle theft and goods

rheft which does not fadlitnte comparable studies.

- TI1e coiJation of i.nfonnation is not always undertaken at a national level.

- Most of tbe sysrems set up by natjonal authorities are intended for operational purposes and

not for analytical ptuposes..

- The categotisation of vehicles is iucous.istent and does not alway djstingui.sh between Ligbl

and Heavy Goods Vehicles.

- Data on the theft of goods is not normaUy collected from the autholities collecting data on

veb:icle theft

Despite these the data show that theft of goods and vehicles is a ignificant problem

costing many mimoru of Euro.

In some countries, up II) J% of the goods vehicles in circulation nre stolen annually - that is many

tens of thousands of commercial vehicles. Th.e infonnatiou on trends shows that the problem is

becoming worse in many countries; thefts of vehicles bet.ween 1995 and ] 999 were anQlysed for

l l countries and while two countries showed decreases, the other countries showed increaes of up ro

50%. The average overall increase for these countries was 2i% over the five year period. The data alsl.,

indica.te very different leveL<; of recovery of stolen vehicles.

rl11e goods stolen are especiaUy electrical and electronic goods. clothes and footwear, aod then

household food. cigarettes and .alcohol. However, there is no known data relating to the value

of goods stole.n from vehJcles at a European level. Insurance comparues. and associations have been, so

far, unable to pmvide compn:iliensive information.

@ ECMT. 2002

11

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

It. is clear that the private ector suffers considerable losses from the theft of goods .in transport.

For example, an initiative by an association of 20 high tech companies to measure the value of goods

' tolen showed between September 1999 and December 2000, 150 incidences of rbeft of which 25%

were bi-jacks. 1lle type of products stolen were all of high value: mairuy computer equipment and

reJated peripbera.ls, or mobi le telephones. The total value of known losses was 32 million Euro.

There are two mnin issues facing the authorities oo.IJecting data on. vehicle theft: -The general

problem of the lack of comparability of clime statistics and -The speci fic one of the of

vehicles and risk factors. 'The former js being reviewed by stati ticiaas under the auspices of the

Council of Europe. The latter is being examined by Europol in an endeav<>ur to establish a prot<>coi for

the member states. Tilis protocol is based partly on the results of this st11dy and includes the

information mentioned below.

Co-ordi.nati.on on thi.s subject between ministries of Transp<m and the Interior is poorly

developed.

There are other sources of infomtation on vehicle and goods crime that this \vork was not able

fully to exploit. ln particular. insurance companies appear to have data but it is not aggregated or

widely available.

In most coonnies vehicle and goods theft is not seen as a priority and few resources are given to

collecting and analysing data on it The same is tme at in1emational l.evel.

Recommendations

l. The collection and analysis of infonnation i essential to the fight against clime in transport.

Regular compilation and lhe gradual impnweroent of data are needed to understand better the

extent and natw-e of the problem and to develop strategies to deal it. Resources need to be

given to these tasks.

2. l r i ' necessary to improve gradually the comparability of available data. For thist t1.vo layers of

information are required: the first concerns the categorisation and identif1cation of vehicles and the

second the categories of goods stolen, the location and mode of theft. TI1e definitions and

categorisation set out in Section 6.2 should be the basis for a standardised data collection format

for the recording of vehicle theft and the theft of goods.

3. In each country. relevant data are available from different .sources (police. imerior n:linisuies,

uansport insurance companies) a:ncl closer contacts and i.mproved co-ordination

between these is needed at. national level.

4. At int.emational level. international organisations such as Interpol and EuropoJ are best placed to

''' ork on improving data on vehicle theft as they are the pui nts of reference for the national police

autho.ritie . In the medium tenn, they should examine how to take on th.i task.

5. In tile short tem1, EQIT could continue to work on this subject in co-operati.on with other

authorities. The data here should be updated iu two years.

6. Private companies. shippers. operators, insurance companies alJ have a keen interest aud can also

contribute to providing a better understanding of the nature of crime and on finding ways to

combat it

12

@ ECMT, 2002

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

2. FRAME\l'ORK

2.1 Sc.ope

The scope of the study is to determine the level of s-tatistics on Cmmnercial vehicle theft and the

theft of goods from or with these \ehi d es. available in Europe. Also to identify the orgarrisati.ons and

groups which can provide information on this subject.

2 .2 Objectlve

Tile objective of the study is to:

-

analyse aU tbe avai [able data on Comm-ercial Vehicles and Goods theft in Europe;

clarif)' rhe tatu of information on the subject';

- enable rhe Eampean Conference of Mjnisters of Transport Steering Group to make

recommendations to the Coancil of 1Vfinisters on how to improve infot'mation dsttabases

relating to commercial vehicle cti.me ..

2.3 Background

Council ofiWinisters ltle.etitig, Berlin Aprill997

A resolution on Crime in Inre mational Transport was adopted by the Mi n.isters during this

meeting. They expressed their concern aboul the sharp increase in criminal act. affecting international

tntllSport especially fraud in the transit system ns well as tbe .theft of vehi cles and goods and attacks on

drivers.

TI1e J\1i ni ters a ked to be kept regularly informed of progre in the implementation of the

re,cotnmendations set out In relation to infotmation and statistics on the extent of clime the Ministers

recommended that competent bodies "e.rami.ne available natiom,d arui intertut:tional data sources with

a view to having mare reliable iJtjbrrnation on tiM exteru of the problem".

Seminar ml Cri.fi'W in Trmtsport., Pari.s- January 1999

From the discus ions ttt the January 1999 eminar, some m.ajor points emerged that bad received

little consideration to date.

One .recommendation related to both of the areas covered in the April 1997 Resolution. This was

the re(:ommendation to improve information on crime, since existj og .fnfonnation had proved

insufficient to gauge the scale of the p:roblern. The informatjon on theft and assatt'lts on drivers

provided in tbe report, CEMT/CM(97)7, was incomplete. tmcoordina.ted and insufficieru:

to confirm the very wklely held opinion among transpmt professionals and tbe authorities responsible

for comba:lin.g crime that the problem was on the increab-e.

@ ECMT. 2002

l3

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

In this regard, the situation had not really improved and it was still not possible to assess the scale

of criminal n.ctivities. However, it was pointed out that efforts have been made and several initiatives

have been tc"tken.

111e January 1999 seminal" poiuted out the beuetlts of developing information systems. It stressed

that there was a difference between "operating ... databases, which were aimed at facilit<:tting

investigations, and "information" databases, whi.cb were designed to gauge the extent of theft, identify

its characteristics. Through detailed analyses of chose character:i.stks (if necessary on limited samples

for a more in-depth analysi ), to improve our insight into factors in cr.in1.e and its mechanism . It was

important t.o standardise concepts and definition for both types of but particularly for the

latter.

Council of 1\finis-ters AtfeetittgJ Wal'saw- May 1999

Dming the Council of Ministers Meeting in Warsaw, the Ministers were presented with a report

which analysed the current sinmtion \Vith regard {O the theft of goods or vehicles ancl atmcks on

drivers, as well as fraud in transit regimes. Thi report note-d that, despite some progress, many of the

issues addressed by the 1997 Resolution were still of concern and that m.ore should be done to

hnp1ement the provisions of the Resofution. "01e report also proposed that a number of new

recomm.e.ndations be added to the Resolution. These regarded issues in the tight of developments

over the past two years (new fonns of fraud and crime, exte1tsion of such crime to aU modes of

growtb in illegal immigration), appear to be of particulu importance.

A u.ew Resolmjon on crime in tnwsport designed to meet these new was approved by

the Council of M.inisters. \"Vitb regard to m.e availability of data sour-ces and infonnation on theft of

goods and vehicles, the. new Resolution recommended that.:

- The EUCARIS system be enlarged through the acx:essiou of new countiies.

ln.temational databanks on thefts of goods and vehicles be expanded.

Europetul Con[enmee of J. tlini.i:te.rs of Transport (ECMT) Steering Group -

November 1999

The ECM'r Secretariat wrote to partidpa.m.s in the 1999 Seminar on crime in transport and to

other bodie.s and people working on the subject f<Or their views on the impl.ementation of the

R: esolutjon and to indicate further concrete steps for this. Based on replies to this letter and following a

propo r1l to the Com..rnitree o.f Deputies, it was decided to set up a Steering Group consisting of

representatives from di:tferent. backgrounds (police. transport }vUru tries, customs, insurance, industry.

etc.) to guide fiuther actions. The General Terms of Reference for the Steering Group were to:

- Make proposals on how ECMT can contribute effectively to implementi ng the tv.o

Re olutio.os on Crime in Transport.

- Suggest ptiorities for ECMT work in line with the decisions of Minister .

- Guide particul ar projects that are to be undertaken.

A project to detenni ne the availability of data sources and infonnatiou on theft of goods and

vehicles was decided upon by the SteeJ:ing Group and Ms Elaine Hardy was asked to car.ry out dlis

study on behalf of ECMT.

14

@ ECMT, 2002

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

2.4 1\{ethodology

The methodo'Iogy for the study of Co.mmercial Vehicle theft and the theft of goods with or from

these vehicles was a follows:

- Draft letters requesting data, data sources and contacts. (The.'!ie letters were s-eo:t to Transpott

Authorities in ECMT Me:mber Countries and other Organisations who might have

infonnation and/or contacts).

Request replies by the end of Mnrch 2000. Proceed with a.n analysis and follow-up of these

replies.

Collate information thal resulted from the response to the follow-up i n order to write an

outline report for the meeti ng of the ECMT Oroup on Crin1e in Transport on 11

111

May 2000.

- Write an interim report by end March.

- Write a final repo11 to be presented at the Steering Group Meeting on t 1m May.

Activities

Contacts were made a.t different levels between January and March 2000: through the Ministries

of 111m$port. Police, 'Ministries of Justice, .Ministries of the Interior and tl.1rough other competent

authorities. The oventU collaboration and response of these organisations enabled th.e task force to

ca.rry rhe study on. the status of Comme:rciat Vehicles and Goods theft in Europe, as. recorded and

repo11ed by these respecti ve authorities.

Sm.ge 1: The first task was to send om a brief questionnaire to organisation throughout Westem

and Eastern Europe to find oontocts and inJormation (see Annex I). The organisations contacted were

Ministries of Transport, Justice. the Interior, Police, Statistics Departments etc. TI1e response to the

first questionnaire was encouraging because it demonstrated that there was information available,

although the extenr of the information was not dear.

Staoe 2: The tas.k of sending out a second questionnaire was divided amongst the same

components of the Steering Group who sent out the first questionnaire (see Annex 2). Tbis

questionnail'e was targeted to the organisations sout'Ced or to the contacts obtained tbrough these

sour-ces in order to complete the Terms of Reference as indicated by the ECMT Secretatiat. The

number of respondents and their answers are detailed in the Summary of the Interim Report (see

Section 2.5).

'TI1e liet<md question.naire was far m.ore detailed than the t1rst and was divided in two parts. Part

one related ro the defi.Ditions of dala records and requested information about methodology of

reoording theft, :the age of the vehicle toleu, definitions of theft. a:nd contacts for further data and

reoords. The Second part of the questionnaire related to the definitions of data records on the Theft and

recovery as \.Vel.'! as the value of Goods Trailers and Goods over a 10 year period.

lnfonnation was also requested about the location, mode and methodology of theft. Every effort was

made by the members of the task force to ensure that the authorities contacted bad te-t,-eived the

questionnaire and were at least a.ttem.pting to M.S\\I'et it.

Overall, the ECMT Secretariat sent out the 2nd questionnaire to 16 contacts in lO countries.

Europol, sent out the questionnaire to police authoritie , in all th.e EU member states and E. Hm:dy sent

out requests to 9 other contacts in va:riou.s countties received from the Research Statistics Department

at the Home Office in England. By the thil'd week of Apti l a reminder was sent to all Central and

@ ECMT. 2002

15

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Eastern European as well as Belgium. Estonja, Italy, Denmark, Spain and Sweden by lvls Hardy, while

Eumpol ensured that Austria., Greece. Portugal and Finland had reeived the questionnaire.

2.5 Summary of the Interim Report

During the month of January 2000, a brief questionnaire was sent to organisations througbont

Western and Eastern Europe to fi nd contacts and infonnation relating to Theft of Goods Vehicles and

Goods.

- 33 organisations .representing 25 countries replied to this questiormaire.

24 organisations representing 2l conntTies replied that there was data and infQrmati{)n

available in their country.

9 of the organisations representing 7 countries responded negatively.

- 4 organisations represent] ng 4 countries did not respond :at aU to the questionnaire.

TI1e data was requested from 5 categolies of organisation and the response from these

organisations was as follows:

Transport .15

Justice 8

Statistics 8

Police " ..')

Custom 1

There were 11 questions pertinent to theft of goods and vehicles, which represented 4 categories

of questions. There is an a\'erage of 67% of data from all the re.'ip(Htding organisation.'>,

(see re ponse) wilh a maximum of 81% for .incidences and historical data to a low of 44% relating to

the value and categories of the good and vehicles stolen, shown as foJJows:

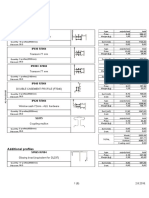

Table l. Data on the theft of goods and \

1

ehides

1.

2.

3.

4.

lncidences of theft and historic."ll data

Value and Categories of goods and vehicles

Location of theft and 1ecovery

Mode and methodology

A l'ailability O'f data

81 %

44 %

&o %

64 %

No action was taken to follow up rhe contacts \Vhere there was no response due to the lack of time

and because alternative sources were identifi.ed.

2.6 Repri!Sentatives and OrgnnisatioDS involved

lvtr Jhi Matejovic of the ECMT Secretariat, !vlessr Hans and Dirk wmde Rys.e of

Europol and Ehune Hardy were directly .involved in finding sources and sending request.s to

organisations throughout Europe for information. Of the 33 organisations contacred the following

organisations responde<l to indicate \Vhether or not they were a.ble to provide data:

16

@ ECMT, 2002

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Table 2. Organisations invQhred

CoWl try Organisation Yes No

Austria Statistics Austria

./

Belarus Ministry of Transport: ./

Belgium Ministry of Commu.nicatkms (Transport}

./

Belgium Dept. of Statistics

./

Czech Republic Minjstt)' of Transport & Commuoications

./

Denmark Ministry of Transport

./

Denmark Denmark Statistics ./

Engl. & \Vales Home Oftice: Research, Development & Statistics

./

Engl. & Wale DEl'R (Department of Transport)

./

Estonia Ministry of Transport ./

Finland Statistics Finland

./

Finland Customs

./

France IHESl

./

France Ministry of [nterior ./

Germany Bu ndeskiiminalarnt

../

Hungary Ministry of TranSJ?Ort ./

Hungary Public Prosecutors Office ./

Netherlands Dept. of Transpott

./

N ether1ands National Police Agency ./

Northern 1Jelaud RUC Statistics Unit

./

Norway Statistics Unit

./

Poland Mini try ofTr.msport

./

Portugal Ministry of Justice

./

Romania Ministry of Transport

./

Russi a Ped. Assembly of tlle Russian Federation

./

Scotti h Exec. Justice Department ./

Slovakja Ministry of Transport

./

Slovenia. Ministry of Transport

./

Sweden Interpol NClD

./

Nat. Counci l for Crim.e Prevention

./

Switzerland

Fed fT

. Ofhce o . ransport

Turkey MLuistty of TtMsport

./

Ukraine Ministry of Transport

./

@ ECMT. 2002

17

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

2.7 Response

The aim of the questionnaire was also to determine whether specific information relating to the

theft of Commercial Vehicles and goods was available to establish whether there was an opportunity

to continue the research. Eleven sub-questions requesting relative iu:furmatiou on incidences and

historical data. were submitted to the organisation . Theil" overall respon.c;e was as follows:

Table 3. Incidenoes of theft

Yes No None

t. lncidences of goods vehicle theft 21 4

.,

-

Incidences of tmHer theft 18 7

3. Incidences of theft of goods froml\vith vehicles !9 6

4. Historical data of the above(> 5 yeal's) 2.0 5

5. The value of the vehlc'les stolen lO 14 1

6. The value of the goods stolen ll 12 2

7. Catego.t)' of goods l2 12 I

8. Location of theft 22 3

9. Loc..'ltion of recovery of stolen vehicle/trailer 17 8

10. 1\llode of theft 13 11 l

11. of recording vehicl.e/trai1er theft 17 7 1

Total 180 89 6

The response to these question.., by country was as foHows:

18

@ ECMT, 2002

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

$::;

-Cl)

-,

--

ll:l

-

N

ll:l

tnt

-(}.

......

\0

Belarus

Belgium

Czech Reeubtic

Deflll'll.lilt

England & Wales

E<>tonia

Fi nland.

France (IHESI)

Fr-ance Min. Int

Germany

Hungary

(Tr-41nspo.rt)

Hungary

(Crim.J'ust)

N etberlands

Northern Ireland

Norway

Poland

Romania

Russia

Slovakia

Slovenia

Scotland

Sweden

Sweden

Turkey

Ukraine

'fotal

---- ------ --

Qx l

Yes No

../

../

.I

.I

../

./

./

./

./

..!

./

./

./

./

./

./

./

./

.I

./

./

./

..!

..!

./

21 4

--- -- -- - -

Qx 2 Qx3

Yes N(} Yes No

../ ./

../ ../

.I .I

./ ./

.

./ ./

../ ./

./ ./

.I

,/

.I ..!

../ ./

./'

./

../ ./

./ ./

./ ../

./ ./

./ ./

.,(

./

./ ./

./ ../

./ ./

./ ./

.

./ ./

../ ./

../ ./

./ ./

18 7 19 6

.

" ---- - - - - -- -- -

Table 4. Incidences of tb.eft by country

.

Qx4 QxS Qx6 Qx 7 Qx S Qx9 QxlO Qx l1 Total

Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes. No Yes No Yes No

../ ./ ../ ../

..j'

./ ../ ./ 7 4

..! ./ ./ ./ ./ ./ ..! ..!

5 6

.I .I .I .I .I ./

,/ . ./

ll 0

.I ./ .../ ./ ./ .I ../ ./

1. 0 L

./ ./ ./ ./ ./ ./ ./ ./

0 l l

..! ..! ./ ./ ./ ./ ./ ./

lJ 0

./ ../ ../ ./ ..! ./ ./

0 lO

../ .I ./ ../ ./ ./

8 1

..! ./ ./ .I ./ ./ ./ ./

4 7

./ ./ ..! ../ ./ ./ ./

9 l

./ ./ ./ ./ ./ ./ ./ ../

4 7

./ ./ ./ .I ../ ./ ../ ./

8 3

./ ./ ./ ../ ./ ./ ./ ./

9 2

../ ./ ./ .I .I ' .!

6 3

./ ../ ./ .I .I ../ ./ ./

7 4

./ ./ ./ ./ ../ ./ ../ ./ 11 0

./ ../

.,( .,(

./ ./ ./ /

8 3

./ ./ ./ ./ ./ ./ ./ ./

10 1

./ ./ ../ ./ ./ ./

,/

./

9 2

./ ./ ./ .I ..! ./ / ./ l.l 0

./ ./ ./ ./ .../ ./ ../ ../

2 9

../ ..! ./ ..! ../ ./ ./ ./ 4 7

..! ../ .I ./ .I ./ ./ ./

lO 1

./ ..! .I .I ./ ./ ./ ./

5 6

..! ./ ../ ./ ..! ..! ..f ./

it 0

20 s lO 14 ll 12 12 12 2.2 3 17 8 13 11 17 7 180 89

- - -- ----- - -- - - -- --- -- - - --- -- - --- - -- -- - -- -- - - - .. - --- - - - -- -- - - --- - --

Note; The responding countries are amalgamated unless the.re is a different respo111se rrorn the organisations thereiii. ln that case, the responses are in-cHeated

_separately.

-

0

.....

tn

7'

-

3

'0

-,

0

3

3. A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF METHODOLOGIES IN EUROPE

TI1is section and Sections 4 and 5 evaluate the information and data collected from the replies to

the second questionnaire.

3.1

11lis section is dedicated to the definitkm of data records. While e.very effort bas be-en made to

ensure tluu the responses in this repo1.t are a refl ection of the I'e->Carding of Commercial Vehicle TI1eft

and the Theft ofOoods in Europe, it mu t be noted that each country has a. method of recording c1ime

statistics which is unique and. bectlLtse of this dlversit)' of nlethodology, the t-aw duta are not

comparable. This questionnaire has endeavoured to examine these differences by identifying the areas

where definitions ma.y blur. Thus the request for cafegories of vehicle weights was included a. well as

the request for the definition of theft and recording proce-dures.

3.2 Methods of rooon:Hng

The purpose of documenting .methods of recording is to understand how each country does this.

The benefit is to enable researchers lo have a clear picture of the background of crirninal statistics

when analysing the data relating, to numbers of thefts and recovelies prese.nted later in this report.

Tirnin;g of recordiTtg incidence

It is important when analysing crime data to consider the timing, because this can and does

dramaticuily change th.e outcome of the connt. In the European Sourcebook of Crime and Crirninal

Justi.ce Statistics prepared by The Emopean Committee on Crime Problems and published in July

1999, specific reference is made to the methodology of counting mles.

"The poim in time in. which the data are recorded varies IJezween. countries.... lf i difficult to

inteq;ret these findings but it .seems saje !.Q assume that the answers "immediately" and

"subsequently"' imply that the legal l.abeliing of ihe offimce is the task of the police (input

statistics) while the annver "after investigation" seems to indicate that the labelling is done by

the pro.secuting authmities (output statistics) once the police elu}uiry has been completetl

1

.. ., "

The main purpose of che question was to detenuine 1;vbe.n che offeuce is recorded: either when it is

reported to the poLice (input statistks) or at a subseqtlent point: in time e.g. when the police have

finali sed their investigation or later (output statistics). Input statistics tend to be more inaccurate and

might over-estim.ate the amount of reported crime. since an invest igatJon hns not yet been conducted?

1. European Sourcebook oa crime and crim.in&l justice stalislics (Cotm<:il of Europe). l. A.2 Comments,

l. A.1. 1. Methodology. (20 July 1999. page 32.

2. European Sourcebook on cri rne and crimina! justice statistics (Counci l of Enrope), Counti ng Rules June,

1995. page 4.

20

@ ECMT, 2002

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

'Wbere the cnuntries have not answered directly (by l'eturniog the questionnaire), the information has

been extracted from the European Sourcebook of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics: Austria, lt,aly,

POitugal. Ru sia, Spain, Turkey.

Austria

BelgiUitl

Czech Republic

Denmark

England & Wales

Estonia

Finland

France

Germany

Greece

Hungary

Irelan-d

Italy

Luxembourg

etberlands

orway

. orthem Ireland

Poland

Pmtugal

Russia

Slovenja

Spain

Sweden

Switze1bmd

Turkey

Table 5. Timing o;f recording incidence

At tbe point of repurtiug

the offence

./

./

./

./

./

./

./

./

./

./

./

./

./

,/

./

,/

After invesUgaUou

or later

./

./

./

,/

./

./

./

J: \tlake L)r tif

Determining the make or model of the vehicle/trailer stolen can help to identit)' those vehicle

which are tnore prone to theft than otbe:ts. Tl:Us may be due to a weal11ess in the security system of the

vehicle or alternatively due to the preference of the Ulief. f"or example a. particular type or model of

@ PJCMT. 2002

21

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

vehicle may have more value for the re.sale of the vehicle as a whole or the spare parts. The question

.a ked was whether the respondents reoorded the make or model of the vehicle or trailer stolen.

Table 6. Recording of make/model, of stolen vehldes/tra.iJer

Yes No

Belgium

./

Czech Republic

./

De am ark

./

England & Wales

./

Estonia

./

Fin! and

./

France ./

Germany ./

Greece

./

Hungary

./

Ireland

./

Luxembourg

./

Netl1erlands

./

No '\Nay

./

No1them lre'laru.i

./

Poland

./

Russia

./

S\vedeo

./

Age of vellide/trailer

'll1-e age of the vehicle or trailer can be helpful in identifying the percentages of vehicles stolen.

Older vehicles may be more vaJnable for tl1eir spare pru1s or may be easjer to steal because of the lack

of seculity systems, \Vhlle newer vehicles may have more value to the tWef if sold on as a whole.

Knowing the age of the vehicle can help to indicate tbe probability of theft over the life span of that

vehicle.

22

@ ECMT, 2002

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Table 7. Recording of age of vehicle

Yes No

Belgium

Czech Republic ./

Denma_rk

./

England & Wales

./

E..stonia

./

Finland

/

France ./

Germany

./

Greece ./

Hungary

Ireland

Luxembourg

./

Netherlands

./

Norway ./

Northern Ireland /

Poland

./

Russia

"

Sweden

./

Definition of tlleft

According to the standard definition in the Council of Europes Crime & Criminal Justice

Statistics sourcebook, 'ttheft" means "depri vi ng a person or organisation of property without force

with the intent to keep it". In some cases this may or .l'lliiy not exclude embezzle.ment (approptiate

fraudulently). Tim there is no clear interpretation in the sourcebook a 0 which statistics are included

or indeed excluded. For example in most continental countrie , the-ft by employees is considered

embezzlement. so may or may not be included.

@ PJCMT. 2002

23

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Delgium

Czech Rep.

Denmark

& Wales

Estonia

Finland

France

Germany

Greece

Hungary

Ireland

Netherland-;

Norway

No.tthern Ireland

Russia

iWis!Jppropriatimz

Table 8. Definition of theft

The illicit removal of propetty belonging to another person.

Code of Crirninal Procedure No: 140/61 Coil., 247 - theft.

Vehicle theft is defined as "theft for use" a11d is specific to vehicle theft.

To permanently deprive the owner of that item/vehicle.

Criminal Code: 139: 140 public 'rhefts; 141: Robbety; I 91: Theft for

temporary us-e.

Approp1iation of mmeable property from the possession of another person

shall be setrtenced for theft to a fine or imprisonment for at most on.e year and

six months.

Pena.l code - o further explanation offered.

Penal Code-No fw1her explanation offered.

The removal (totally or partially) of a movable pmperty from the pos ession

of another person with a view of illegally approptiatjng ic An. 372 of the

Hellenic Penal Code.

Verified Appropriation is stealing; Somebody taking o.mething away from

another person beQ\use heJshe to appropriate it unlawfully.

Any person who steals without consent of the owner. fraudtdently & without

a claim of right made in good faith. takes & carried away anything capable of

being with intent .at the time of such raking, penmmently to deprive the

ovmer thereof.

Defined by law aud statements are distinct in relationship with articles in the

criminal code.

Any person. who any property belonging wholly or partially to any

other person with the imention of unlawfully appropriating it shall be g11ilty

of theft.

Simple and aggravated thef1.

A person is guilty of theft is he dishone tly appropriates property belonging

to another \\.'ith the intenlion of permanently dep1iving the other of it.

A hidden act ofstea.Jing sornebody's property- Art. I 58 ofthe Criminal Code

of Russia.

A pet;' On with intent of unlawfully approprhtting \vhat beloogs to another. If

this involves loss the person Is sentenced for theft with irnprisorunent for 2

yeur.

In some other countries i.n Eumpe, tJ1ef1: also .includes mi.o;appropriation OI tbet't by deception -

whether this can also be interp!'eted as embezzlement is uncleat. England and Wales and possibly

24

@ ECMT, 2002

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Ireland include "conversion"; hire vehicle theft and may include fraud. Also in some counnie , this

defmition may also exclude propett)' not in oontrol of the ownet"'. So within the of

these interpretations, a proportion of vehicles will be excluded from being recorded in many CtJUntries.

Table 9. Taking into account of misappropriation

Yes No Oth:el'

Belgium ./

Czech. Republic

./

Denmark

./

England & \Vales

./

Estonia

Finland

./

France

..1

Germany

./

Greece

./

Hllliga.ry

./

lreland

./

etl1erlands ./

Non"'ay

./

.orthem Ireland

./

Poland

./

Russia

./

Sweden

./

Temporary u.se

The theft o:f a vehicle leaves the recording of this offence open to interpretation if the veb:icle is

recovet'ed "Vithin a specific point in lime. Each country appeurs to have a specific definition of

u e .. and in some countiies this means that by definition, .. temporary use" is excluded

from the count of r-eco1'ding that offence. Also. the offence of ' joyriding; with commercinl vehicles is

less likely than witb cars. TI1is definition "vhrcb eems t() infer "temporary may or may not be

included in some countries. According to th.e CounciJ of Europe' s sourcebook, Hungary, Italy and The

Nethel"l""UJds exclude both joyriding and temporary use.

@ PJCMT. 2002

25

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Table 10. Taking into aeemmt oftempcOrary use

Czech Republic

Demnark

England & Wales

Finland

France

Gel'lJ'Ullly

Greece

Hungary

Ireland

Italy

Luxembourg

Netherlands

Norway

Northern: Ireland

Pol.and

Ru. sia

Sweden

S'Ad tzerland

Yes No

./

./

./

./

.(

./

./

./

.;

./

../

.;

./

../

./

./

./

.;

Note: Response for S'>vitzerland, rtaly and Hungary

from CouncPI of Et1rope' Crirne & Criminal Justice

Statistics sourcebook 1999<.

DefiJlition. use

For e.xamp1e, in England & Wales, there is th.e offence of ' \mauthorised taking of a motor

vehicle". In 1960, tbe length of recovery \Vhich determined tbe offence, became 30 days. H.owever, if a

vehicle is recovered within this time and it appears lhut the offender has assumed lhe right of the

owner" then this would be recorded as theft. This i also the case for Ireland, thus for both these

countries .. !'temporary use" as uch is ubjective. l n Finland. temporary u e is defined .as unauthorised

use. u.su.aUy one week but a time limit is not defined in the Penal Code. In the term

"'unaurhotised taking" is used for theft of vehicles for a period of t\vo montbs. After two months it is

recorded as a larceny.

26

@ ECMT, 2002

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Belgium

Czech Republic

Denmark

En,gtand & W rues

Es.tonia

Finland

France

Germany

Greece

Hungary

Ireland

Luxembourg

Netherlands

Norway

Northern Ireland

Pohmd

Russia

Sweden

3.3 Location

Table l l . Definition of temporary use

< 24 boors < 48 hours < 1 week Ollie

No defi.niti.on

Pemtl Code

" Tbeft for use"

30 day .

No lirni t

./

./

A very short period of time

No definition

2 months.

No definition

No Limit

./

No

No defini tion

No defi nition

No definition

OftJteft stollm vehicle or trailer

TI1e purpose of this question was to detemline whether d1e location of the theft of vehicles or

trailers was recorded by the authorities. The reason for this is to enable analysts to identify areas which

are more vulnerable than others.

@ PJCMT. 2002

27

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Table. 12. Recording oflocation of theft

Belgium

Czech Republic

Dertmark

England & Wales

Estooi.a

Finland

France

Germany

k elaud

Luxembourg

Netherlands

Nonvay

Northern Ireland

Poland

Russia

Sweden

QfrecJJvery o.fs.tole.rz vehicle or trailer

Yes

./

./

../

./

./

./

./

./

../

./

No

Th.e purpose of identifying locations \\'here the vehicle or trail.er are recovered is to assess co

operation berween authoriti es,. best practices and modus operandi of the offenders.

Table 13. Recordi11g of loeatJon of rreov.ery of stolen vehicles

Belgium

Czech Republic

Denmark

England & Wales

R<ttonia

Finland

France

Gennany

Ireland

Luxembourg

ether lands

.orway

ortbern Ireland

Poland

Russia

Sweden

28

v .

1es

./

./

./

.;

../

../

../

../

../

./

No

../

./

./

./

./

./

@ ECMT, 2002

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

3.4 !\{ode of theft

The fundamental difference in studying HGV theft compared to car theft i the 'int.ent'. There are

two ~ p e i f i reasons why commercial vehicles are stolen: For the goods t11ey carry as well as for the

vetticle. Five questions relating to people,. means of transport, technology used and aggression were

asked. The response to these questions was very limit-ed. l t i s reasonable to ru>"sume that there are no

aggregate statistics .made nva:ilable by countries to determine the level of Mtiona.l information on these

issues. Any organisational or natiorud information wiU be cartied in the foll()wing section

"'I nformation by Country".

l,)eople involved

The purpose of trus question is to detemtine whether one or more than one person was involved in

the offence. This indicates that the theft may be either oppottunistic or profession.'i\1. (organised).

Estonia and Russia (Insurance Association) answered tllis question- Russia gave no figures .

. Means oftrtUtSport

When stealing trailers or goods. the criminal does not only u e the vehicle cru.1-yi11g the goods or

pulling tbe trai ler. Knowledge of how the trailer Ol' goods are removed from the vehicle can help

identify patterns and trends aJ:ld can. also i.ndieare whether t:he theft was plao.ned previously.

Estonia and R.uss.ia (Insurance Association) answered this question- Ru sia gave no figures.

Use ofteclmolcgy

The use of technology by the offender can help to indicate whether professiom1J thieves are

involved. As security systems become more <:omp!icated, the chance of opportunistic thieves breaking

into a vehicle become more remote. Thus by d.ete.nniiling the level o:f professionalism of the thie:f can

.as ist .manufacturers .and authorities to improve their ecmity.

TI1e Netherlands and Estonia responded and gave indications of incidences. Russia (Insurance

Association) answered this question affulnati.vely - no figures given.

Vit!leJU:e

AnecdotaJ evidence suggests that violent theft o.f vehicles nnd goods is increasing. The reason

may be because security bas improved or simply because there i more involvement of organised

criminals. Knowledge of trus infom1ation can he4J to assess the risk factor for drivers.

TI1e etherlands England & 'Wales (Essex J>olioe), Estonia and Russia (Insurance Association)

responded and gave indicati.ons of incide11ces.

@ PJCMT. 2002

29

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

There seems to be uncertainty as to the exact definition of the word "hijacking''. In these cases it

means when Ehe dtiver is tlu-eatened with firearms or menace and is kidnapped \Vith the vebicle. The

defm.itiou "jacking" in connection with theft of velticles of whate\'er category. has taken on a different

meaning in some countries. TI1e Belgian authorities for example, .have taken to using the definition

car-jacking" to mean "th.eft with menace" the pmp ose appears to be related to the 11eed of the

offender to rake possession of tbe electronic ''key''' or "transponder" itt order to open and starr the

vehicle.

TI1e Netherlands England & Wales (Essex Police). Rus ia (Insurance A sedation) responde-d and

gave indications of incidences. The High Tech Inauufacturer.s association TAPA-EMEA was able to

give details whjch represented 25% of all incidences.

Robbery

The definition of robbery here is theft witll mennce, tb.at is to say that the offender threatens the

victim witb or without arms and steals the goo<Lc; or vehicle in the presence of the victim. However, the

Council of Europe's sourcebook points out that the definition of mbbery cun vary and this is boc:ause

of the non-e xistence of cettaiolega] concepts in certain countries.

The etheriands Engl<md. & WaJes( Essex Police). Estonia and Russia 01umraoce Association)

responded affinnati vely and gave indications of incidences.

3.5 Condusions

The purpose of gatherin,g infonnation aoout definitions and methods of reporting and recording

vehicle theft, was to understand whether there were variations of a greater or smaller magnitude. The

reason for this wa ro determine whether these methods tu1.d definitions cou1d distort the .final picture

of the statistic" colle.c.ted and analysed in the next section.

'7':. .F , ;, "'d

"' utung OJ recoru1ng met ence

Twenty five countries. were analysed for this question.

Table 14. Rec;ording of incidence

At point 0-f reporting of the offence After investigation or later

17 8

Make 0.1 of JJelzicle/trailer

Eighteen countries were analysed for this question.

30

@ ECMT, 2002

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Table J 5. Recording of make or model of the stol-en vehicle/trailer

Yes No

Number of Countries responding 15 3

Age tif v,ehicl..eltrail'er

Ejghteen countries were imaly ed for this question.

Table 16. Reco-rding of age of t he vehicle/trailer stolen

Yes No

Number of Countries responding 7

Definition of theft

Eighteen countries were analysed for thls question. Seventeen countries answered the survey.

Eighteen countries were analysed for t.bis question.

Table 17. Taking iuto accow:tt of misappropriation

Yes Other n.a.

Number Of Countries respondi ng 13 2 .I 2

Temporary u.s.e

Twenty countries were analysed for this question.

Table; 18. Taking into a.ceount of temporary use

Yes No

Number of Countries respond1ng 12 7

Defiuition tt vlpor.ary u,se

Eighteen countries were analyse-d for this question.

@ PJCMT. 2002

31

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Table 19. Definition oftemporary use

Number of countries responding < 24 hours < 48 boors < 1 week Other

2 16

Loc..ation

a) Of theft stolen vehicle or trailer

Sixteen countries were analysed for this question.

Table 20. Reoordiug of location of theft

Yes No

Number of count.Jics responding J5 1

b) Of recovery of stolen vehicle or trailer

Sixteen countries were .analys-ed for this question.

Table 21. Recordiug of loeatJon of reco,r.ery of stolen vehicles

No

Number of countries responding 6

TI1e Group that prepared the Eumpean Sourceboo-k of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics

published first in June 1995 and again in July 1999. put a lot of effort into collecti.ng quantitative data

in order to see how comparable data on cri me and crirrunal justice statisti s in Europe were. Tbey

tbun.d tllac there were vast difference in counting \'\'hich wa due to the variati.on of legal concepts in

Europe and the way that each nation collects .r:md presents i(s S[atistics. They commented: "tile lack of

uniform definitions of offences, of common measuring instruments and of conunon methodology

makes comparisons between countries extremely hazarclous"l.

Thi section has providerl sufficient information to concur with the Europe's sourcebook

and demonstrate that that any consideration of the statistics provided in this report rnust only be

considered in the light of those observation.s.

1l1c lack of information concerning the mode of tbeft is obvious. There are some pockets of

information given. whl.ch has be-en reponed lA>ithin the section dedicated to tbe country anal ysis.

Overall there seems to be no consistent aggregated coUection and ana.ly:is of this type of information.

3. So\lrcebook of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics. 0.6 CompEU'abHity. J 1.dy l 999. page 11.

32

@ ECMT, 2002

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

'Whether there are separate bodies gathering these facts, i s not clear. However there does not seem to

be amongst authol'ities. this information i either not passed on for gathering at a

national level or simply the information is not deemed important enough to record.

4. COUNTRY PROI"lLES

Int

Because of the variation of sources and the quality of infotmation at national level, the data

received :relating to the numbers of incidences of d'1eft of goods and v-ehicles did not always fit into the

.format of the quest1onn.a:ire. l n sornt:1 cases the catego1ies of goods and vehicles stolen were nor total

annual figures but isolated Incidences. I.o other cases. the information on tbeft of vehicles and goods

was just not available in a format. that could be analy ed for the purpose of creating comparative trends

or oveiVtews.

While every attempt has been made to create an overview of commercial vehicle theft in Europe

a11d at national level, it seemed necessa.ry to document the data relati ng to each country as tl1ey were

presentedi rather than attempt to inte1pret them. This section illustrates the type of intbrmation made

available by the respecti ve authorities aud o.rganisarion answering the questionnaire. In some cases:

Spain and partly Belgium and the Netherlands, data received from Europol relating to the theft and

recovery of Commet'(...ial VehicJes is also reported herein.

Th.e counnies included in this section are: Austria, Belgium., Czech Republic, Denmark. Estonia,

Fi nJaod, France, Germaoy, Greece, Hungary, ireland, Italy, Luxembourg. Netherland-;, Norway,

Poland, Russia, Sweden, Turkey and United Kingdom ..

4.1 Austria

Mag. Rupert S pdnzl

rvHnisuy of lnterior

Interpol Vienna

Tel: 00 43 1 31345 85430

Email: RupertSPRINZL@bmi.gv.at

111ese data for Austria were received fJom the Austrian Police and cover the pe1iod 1994 to 1999.

There was no indictttion whether these statistics refer to Conm.1ercial Vehicles of all categories or only

vehicles over 3.5 tonnes.

@ PJCMT. 2002

33

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Table 22. Theft and recovery of commercial "'ehicles in Austria

Then of (;ommercial vehicles

Recovery of commercial

vehicles

Recovery rate of commercial

vehicles

800

700

600

500

400

300

200

100

0 -t-

1994

402

257

64 %

1995 1996

444 623

268 440

60 % 71 %

.Figure 1.

1994 1995 1996 1997 1998

4.2 Belgium

' flle data for 1999 for Belgium was from:

Gendarmerie-Bureau central de recherches

Av. de Ia Force aerienne 10

1040 Bruxcllcs

M. Claude Vandcpittc and M Kurt Boudry

Tel: 0032 2 6427990

Fax: 0032 2 6427834

% Recovery Rate 1

1997 1998 1999

683 242 253

445 132 131

65 % 54.5 % 51.7 %

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

1999

The data for 1993-2000 indicate theft and recovety of as well as attempts of theft for both

categories of vehicles. There are no statistics avai lable for the theft of trailers or goods.

34

ECMT, 2002

MatenJal zastrcen autorskrm pravom

Table 23. Theft and recovery of commercial vehicles in Belgium

1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000

Total theft

< 3.5 tonnes l 287 1 509 1 659 1 854 2 086 2075 2 298 2 268

> 3.5 tonncs 200 250 279 253 36 1 343 255 282

Tractor 90 138 167 I 3l 19l 225 154 164

Total J 577 I 897 2 J05 2 238 2 638 2 643 2 707 2 714

Recovered

< 3.5 tonnes 783 837 925 I 176 1 211 1 238 1 347 I 296

> 3.5 tonnes 108 132 162 153 194 182 152 154

Tractor 39 81 68 77 125 115 77 113

Total 930 1050 ] 155 1 406 I 530 t 535 1576 ] 563

Attempts

< 3.5 tonne 4 14 9 65 135 204

?- 1 _,:,

238

> 3.5 tonncs 4 5 2 17 22 52 59 49

Tractor 0 0 1 0 6 10 29 25

Total 8 19 12 82 163 266 339 312

Recovered vehicles 59% 55 % 55 % 63 % 58 % 58 % 58 % 58%

3000

2 500

2000

1 500

1 000

500

0

Figure 2. Commercial vehlcles stolen in Belgium 1993-2000

1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2GOO

Total theh % Recovered

64%

62%

60%

56%

54

0 (

10

52%

50%

@ ECMT, 2002 35

MatenJal zastrcen autorskrm pravom

4.3 Cze:cb .Repu bUc

Ministry of Transport & Communications

POBox 9

Nahrezi Ludvika Svobody 12/22

Prague 1 CZ- I 1- t 5

Jana Rybeaska

Tel: 00420 2514 31223

Fax: 00420 2 24 81 22 93

Email: rybenska @rndcr.cz

l l1e definition of both tractor and Jony is assumed to mean the cab of a heavy goods vehicle

though possibly of a different weight, however no category of vehicle weight was included ..

Table 24 .. Theft and recovery of commercial vehicles in the Czech Republic

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999

Lorry

Theft 16 119 359 365 411 507 703 903 813

Recovery 7 31 112 137 121 183 262 302 251

Recovery rate 44 % 26 % 31 % 38 % 29 % 36 % 37 % 33 % 31 %

Trailer behind a

lorry

u ~ f t 4 59 151 126 119 !37 132 143 154

Recovet1' 0 5 21 27 31 23 34 52 40

Recovery rate 0 % 8 % 14 % 2l o/ 26 % 17 % 26 % 36 % 26 %

Tractor

Theft 4 33 37 44 43 63 7I 62

Recovery 2 9 15 21 19 31 37 41

Recovery rate 50 % 27 % 41 % 48 % 44 % 49 % 52 % 66 %

Trailer behind a

tractor

Theft l 31 47 45 47 68 78 81

Recovery 0 9 14 21 22 41. 38 49

Recovery rate 0 % 29 % 30 % 47 % 47 % 60 % 49 % 6J %

Conunercial

vehicles

Total theft 20 183 574 575 61. 9 734 966 1 195 l 110

Recovery 7 38 151 193 194 247 368 429 381

Recovery rate 3"'%

.)

21 % 26 % 34 % 31 % 34 % 38 % 36 %

34 l.!1.

10

111e following graph shows the theft of' commercial vehicles in Czech Republic and the

percentage rate of recovery of these vehicles.

36 @ ECMT, 2002

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

1400

1200

1000

BOO

600

400

200

0 -+---+-

1991 1992 1993 1994

1- Theft

4.4 Denmark

Rigspolitichdens Afd. A Polilitorvet 14

DK- 17RO

Derunark

Relations l nte1pol Copenhagen

Det. Chief Inspector Hans Ellehauge

Tel: 0045 33 14 88 88

Fax: 0045 33 32 277 I

Figure 3.

1995 1996 1997

% Recovered

1998 1999

40%

35'%

30%

25%

20%

15'%

10%

5%

Table 25. Theft of commercial in Denmark

1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999

Theft of vehicles 4 133 3 861 4 224 4 793 5 118 4 946 4 566

No recovery rate of commerci al vehicles stolen is available. The following graph shows the total

number of commercial vehicles stolen each year and these vehicles as a percentage of commercial

vehicles registered in thi s counU)'.

ECMT, 2002

37

MatenJal zastrcen autorskrm pravom

Figur e 4.

Theft of Commercial Vehicles in Denmark

6000

5000

4000

3000

2000

1 000

0+-

1993 f994 1995 1996 J997 1998

Theft % ol Pare I

1.6%

1.4%

1.2%

1.0%

0 .6%

0.6%

0.4%

0.2%

--+- 0.0%

1999

Overal L 24 incidences of theft of Commercial Vehicles arc reported by lhe Danish Insurance

Association over a three year period from various location .

Danish Insurance Associari on House of Danish Insurance

Amaliegade JO

DK- 1256 Copenhagen K

Tel. +45 3343 5500

Fax +45 3343 5501

Email : f p@ ForsikringensHu:;.dk

It is not clear whether these incidences took place within Dani sh teJTito.ry or elsewhere. The total

value for claims relati ng to these incidences was declared as 56 million Euros.

Overall

Average

Number of incidences

Table 26. Value of goods stolen (in Euros)

1996

(millions)

4.5

1.5

3

1997

(millions)

38

18.8

1.9

lO

1998

(miUions)

20.6

2 .. 6

8

1999

(millions)

11.9

4

3

@ ECMT, 2002

MatenJal zastrcen autorskrm pravom

Table 27. Type of goods stolen (number of incideuces)

1996 1997 1998 1999

Food 2 2 l

Elect1ical

j

Hourehold

Electronic 2 2

Alcohol

Metal

Clothes 3 .I

Footwear

!vlisc. 1 2

Cigarettes 1 I 3 2

4.5 Estonia

The information for Estonia came via the Estonian Road H.auliers 1 ociation in collaboration

with the :<onian Police.

Estonian I ntemation.a.J RoadHa.uhe.rs Association

Narva mur 91

10 127 Ta1linn Estonia

Mr Laud. Lusti

00 372 627 3750

00 372 627 3741

Estonian Po.lice Board

l Pagari. Street

Tallinn Estonia

Tel: 00 372 612 33 17

Fax: 00 372 627 3741

The data p:rovided are quite detailed and give a very good indication of the theft rate and the value

of goods tind veb.ides. Wh<lt has not been made cleat is the categories of commercial vehicles stolen.

The infommion regarding values of good stolen highlights that over a 7 year period-. 17.5 miUi{)n

Eu.ros worth of goods have been stolen frorn vehicles in this country. Other detailed information which

serves to upport the concerns of d1e authorities is the leveJ of thefts from vehicles for uch a smalJ

country aud the number of lncidences of violence and robberies against tl1e drivers.

@ PJCMT. 2002

39

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Tab I.e 28. Theft a.nd r ecovery o.f vehicles aud goods in Estonia.

Theft of comm.erciai vehicles

Recovery of commercial vehicles

Recovet-y rate

Goods stoien with conunercial

vehicles

Goods tolen fmm conunerciat

vehicles

Goods stolen from commercial

vehic1es and later recovered

Value of vehicle in Euros (OOOs)

Overall

Number of incidences

Average

Value of goods stolen in

Overall (in millions)

Average

Number of incidences

Type of g<)ods stolen

Food

Electrical

Household

Electronic

Alcohol

Metal

Clothes

Footwear

Misc.

Cigarelles

1993 1994 1995 1996. 199? 1998 1999

27 37

")3

... 48 40 57 ">9 ....

2 ll

-

J 13 15 16 12

5.4% 30 % 22% 27% 38% 28% 41 %

1 l l 2 7

3887 4354 5667 5413 6012 7958 9341

404 467 67l 783 979 882 l OOl

40 63 39 54 35 289 237

1.1 12 9 20 14 18 l l

4 5 4 3 2 16 22

1.4 1.5 2 2 2.8 3 4.8

361 348 367 362 344 355 515

3 887 4 354 5 667 5 413 6 012 7 958 9 341

50 46 70 62 61 61 69

17 21 18 21 31 34 39

54 59 62 28 43 57 75

28 19 26 19 28 31 27

2 3 3 4 2 2

220 221 254 240 285 472 56(}

60 41 60 45 42 58 36

I 354 l 869 2106 2297 2614 4013 5 026

16 24 28 t7 30 29 43

40

@ ECMT, 2002

Materijal zasticen autorskim pravom

Figure 5. Theft of commercial vehi cl es in

00

50

40

30

20

10

1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999

Theft % Recovered

Mode of theft

I. Use of more than one person

2. Use of other means of transport to remove the vehicle

45%

35%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

3. Use of technology ro enter/remove vehicle (i.e. radar systems, disarmjng immobilisers etc)

4. Use or violence to steal vehicle/goods

5. I ncidences of hi-jacking (Kidnappi ng of the driver with the vehicle)

6. Incidences of robberjes (theft with menace)

Table 29. Mode of theft

1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999

J. L48 199 201 200 202 252 217

2.

3.

4. 17 35 32 16 16 13 23

-

).

6. 24 40 30 21 11 21 10

4.6 Finland

data for commercial vehicle lheft 1993 and 1997 are from Europol. There is no

indication whether these vehicles are intended ro be all commercial vehicles or only the category of

@ ECMT, 2002

41

MatenJal zastrcen autorskrm pravom

Jess than 3.5 tonne . 1l1c data for 1997 (>3.5 tonnes) and the data for 1998-99 arc from the Finnish

ational Bun:au of Investigation.

Natjonal Bureau oflnvestigation

Crimi nal I ntelligence Di vi sion

Box 285. 0 1301 Vantaa

.Jari ystrom Detecti ve SuperinLendenl

Tel: 00358 9 8388 66 1

Fax: 00 358 9 8388 6284

Table 30. Theft and rccovcrv of commerdal vehicJcs in Finland

Theft of vehicle

< 3.5 tonncs

> 3.5 tonnes

Trailers

Total

Recovered vehicles

< 3.5 tonncs

> 3.5 tonnes

Trailers

Total

Recovery rate

I 400

I 200

l 000

aoo

600

400

200

0

1993 1994 1995 1996

989 919 758 789

n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a.

n. a. n.a. n.a. n.a.

n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a.

81J 78 1 613 644

n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a.

n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a.

n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a.

82 % 85 % 81 % 82 %

Figure 6.

Theft of Light Commercial Vehicles in Finland

1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998

1997

925

12

n. a.

n. a.

79 1

n.a.

n.a.

n.a.

86 %

1999

1998

1092

86

719

I 917

910

72

372

1 354

83 Gk