Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

SME Bank Inc. V.de Guzman-Et-Al

Încărcat de

Roberts Sam0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

127 vizualizări20 paginiThe Supreme Court of the Philippines consolidated two cases involving employees who were terminated after a change in ownership of SME Bank. The employees filed complaints against both the previous and new owners claiming illegal dismissal. The labor arbiter ruled that while the new owners were not obligated to retain the employees, the employees were illegally dismissed because they resigned involuntarily based on representations they would be rehired. The labor arbiter ordered the previous owners to pay separation pay but dismissed the case against the new owners.

Descriere originală:

wadawdddddawdawdadad

Titlu original

SME Bank Inc. v.de Guzman-Et-Al

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentThe Supreme Court of the Philippines consolidated two cases involving employees who were terminated after a change in ownership of SME Bank. The employees filed complaints against both the previous and new owners claiming illegal dismissal. The labor arbiter ruled that while the new owners were not obligated to retain the employees, the employees were illegally dismissed because they resigned involuntarily based on representations they would be rehired. The labor arbiter ordered the previous owners to pay separation pay but dismissed the case against the new owners.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

127 vizualizări20 paginiSME Bank Inc. V.de Guzman-Et-Al

Încărcat de

Roberts SamThe Supreme Court of the Philippines consolidated two cases involving employees who were terminated after a change in ownership of SME Bank. The employees filed complaints against both the previous and new owners claiming illegal dismissal. The labor arbiter ruled that while the new owners were not obligated to retain the employees, the employees were illegally dismissed because they resigned involuntarily based on representations they would be rehired. The labor arbiter ordered the previous owners to pay separation pay but dismissed the case against the new owners.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 20

--

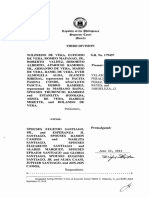

l\epublir of tbe lJbtlipptnes

;ffianila

ENBANC

SME BANK INC., ABELARDO P.

SAMSON, OLGA SAMSON and

AURELIO VILLAFLOR, JR.,

Petitioners,

-versus-

PEREGRIN T. DE GUZMAN,

EDUARDO M. AGUSTIN, JR.,

ELICERIO GASPAR, , RICARDO

GASPAR JR., EUFEMIA ROSETE,

FIDEL ESPIRITU, SIMEON

ESPIRITU, JR., and LIBERATO

MANGOBA,

Respondents.

X-------------------------X

SME BANK INC., ABELARDO P.

SAMSON, OLGA SAMSON and

AURELIO VILLAFLOR, JR.,

Petitioners,

-versus-

ELICERIO GASPAR, RICARDO

GASPAR, JR., EUFEMIA ROSETE,

FIDEL ESPIRITU, SIMEON

ESPIRITU, JR., and LIBERATO

MANGOBA,

Respondents.

G. R. No. 184517

G. R. No. 186641

Present:

SERENO, CJ,

CARPIO,

VELASCO, JR.,

LEONARDO-DE CASTRO,

BRION,

PERALTA,

BERSAMIN,

DEL CASTILLO,*

ABAD,

VILLARAMA, JR.,

PEREZ,

MENDOZA,*

**

REYES,

PERLAS-BERNABE, and

LEONEN,JJ

Promulgated:

October 8, 2013

x----------------------------------------------- --x

*Took no part. Concurred in the Court of Appeals Decision (CA-G.R. SP No. 97510).

**On lf';JVP

Decision 2 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

D E C I S I O N

SERENO, !":

Security oI tenure is a constitutionally guaranteed right.

1

Employees

may not be terminated Irom their regular employment except Ior just or

authorized causes under the Labor Code

2

and other pertinent laws. A mere

change in the equity composition oI a corporation is neither a just nor an

authorized cause that would legally permit the dismissal oI the corporation`s

employees en masse.

BeIore this Court are consolidated Rule 45 Petitions Ior Review on

Certiorari

3

assailing the Decision

4

and Resolution

5

oI the Court oI Appeals

(CA) in CA-G.R. SP No. 97510 and its Decision

6

and Resolution

7

in CA-

G.R. SP No. 97942.

The Iacts oI the case are as Iollows:

Respondent employees Elicerio Gaspar (Elicerio), Ricardo Gaspar, Jr.

(Ricardo), EuIemia Rosete (EuIemia), Fidel Espiritu (Fidel), Simeon

Espiritu, Jr. (Simeon, Jr.), and Liberato Mangoba (Liberato) were employees

oI Small and Medium Enterprise Bank, Incorporated (SME Bank).

Originally, the principal shareholders and corporate directors oI the bank

were Eduardo M. Agustin, Jr. (Agustin) and Peregrin de Guzman, Jr. (De

Guzman).

In June 2001, SME Bank experienced Iinancial diIIiculties. To remedy

the situation, the bank oIIicials proposed its sale to Abelardo Samson

(Samson).

8

Accordingly, negotiations ensued, and a Iormal oIIer was made to

Samson. Through his attorney-in-Iact, Tomas S. Gomez IV, Samson then

sent Iormal letters (Letter Agreements) to Agustin and De Guzman,

demanding the Iollowing as preconditions Ior the sale oI SME Bank`s shares

oI stock:

1

CONSTITUTION, Art. XIII, Sec. 3.

2

LABOR CODE, Art. 279.

3

Rollo (G.R. No. 184517), pp. 17-53; Petition dated 22 September 2008; rollo, (G.R. No. 186641), pp. 3-

46; Petition dated 10 March 2009.

4

Rollo (G.R. No. 184517), pp. 58-71; CA Decision dated 13 March 2008, penned by Associate Justice

Romeo F. Barza and concurred in by Associate Justices Mariano C. del Castillo (now a member oI this

Court) and Arcangelita M. Romilla-Lontok.

5

Id. at 73-74; CA Resolution dated 1 September 2008.

6

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), pp. 54-66; CA Decision dated 15 January 2008, penned by Associate Justice

Rosmari D. Carandang and concurred in by Associate Justices Marina L. Buzon and MariIlor P. Punzalan

Castillo.

7

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), pp. 68-69; CA Resolution dated 19 February 2009, penned by Associate Justice

Rosmari D. Carandang and concurred in by Associate Justices Martin S. Villarama, Jr. (now a member oI

this Court) and MariIlor P. Punzalan Castillo.

8

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), pp.11-12.

Decision 3 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

4. You shall guarantee the peaceIul turn over oI all assets as well as the

peaceIul transition oI management oI the bank and shall

terminate/retire the employees we mutually agree upon, upon transIer

oI shares in Iavor oI our group`s nominees;

x x x x

7. All retirement beneIits, iI any oI the above oIIicers/stockholders/board

oI directors are hereby waived upon cosummation |sic| oI the above

sale. The retirement beneIits oI the rank and Iile employees including

the managers shall be honored by the new management in accordance

with B.R. No. 10, S. 1997.

9

Agustin and De Guzman accepted the terms and conditions proposed

by Samson and signed the conforme portion oI the Letter Agreements.

10

Simeon Espiritu (Espiritu), then the general manager oI SME Bank,

held a meeting with all the employees oI the head oIIice and oI the Talavera

and Muoz branches oI SME Bank and persuaded them to tender their

resignations,

11

with the promise that they would be rehired upon

reapplication. His directive was allegedly done at the behest oI petitioner

Olga Samson.

12

Relying on this representation, Elicerio,

13

Ricardo,

14

Fidel,

15

Simeon,

Jr.,

16

and Liberato

17

tendered their resignations dated 27 August 2001. As Ior

EuIemia, the records show that she Iirst tendered a resignation letter dated

27 August 2001,

18

and then a retirement letter dated September 2001.

19

Elicerio,

20

Ricardo,

21

Fidel,

22

Simeon, Jr.,

23

and Liberato

24

submitted

application letters on 11 September 2001. Both the resignation letters and

copies oI respondent employees` application letters were transmitted by

Espiritu to Samson`s representative on 11 September 2001.

25

On 11 September 2001, Agustin and De Guzman signiIied their

conIormity to the Letter Agreements and sold 86.365 oI the shares oI stock

9

Rollo (G.R. No. 184517), pp. 120, 122; Letter Agreements.

10

Id. at 121, 123.

11

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), p. 13; Petition dated 10 March 2009.

12

Id. at 126; Position Paper Ior Complainants dated 20 September 2002.

13

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), p. 134; Resignation Letter oI Elicerio Gaspar.

14

Id. at 135; Resignation Letter oI Ricardo M. Gaspar, Jr..

15

Id. at 136; Resignation Letter oI Fidel E. Espiritu.

16

Id. at 139; Resignation Letter oI Simeon B. Espiritu, Jr. dated 27 August 2001.

17

Id. at 137; Resignation Letter oI Liberato B. Mangoba.

18

Id. at 138; Resignation Letter oI EuIemia E. Rosete.

19

Id. at 171; Retirement Letter oI EuIemia E. Rosete; rollo (G.R. No. G.R. No. 186641), p. 141; Letter oI

Simeon C. Espiritu to Jose A. Reyes transmitting, among others, the Retirement Letter oI EuIemia E.

Rosete.

20

Id. at 145-146; Sinumpaang Salaysay oI Elicerio Gaspar dated 20 September 2002.

21

Id. at 147-148; Sinumpaang Salaysay oI Ricardo Gaspar, Jr. dated 20 September 2002.

22

Id. at 143-144; Sinumpaang Salaysay oI Fidel E. Espiritu dated 20 September 2002.

23

Id. at 149; Undated Sinumpaang Salaysay oI Simeon B. Espiritu, Jr.

24

Id. at 150-151; Sinumpaang Salaysay oI Liberato B. Mangoba dated 20 September 2002.

25

Rollo (G.R. No. 184517), pp. 543-544; Letters dated 11 September 2001.

Decision 4 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

oI SME Bank to spouses Abelardo and Olga Samson. Spouses Samson then

became the principal shareholders oI SME Bank, while Aurelio VillaIlor, Jr.

was appointed bank president. As it turned out, respondent employees,

except Ior Simeon, Jr.,

26

were not rehired. AIter a month in service, Simeon,

Jr. again resigned on October 2001.

27

Respondent-employees demanded the payment oI their respective

separation pays, but their requests were denied.

Aggrieved by the loss oI their jobs, respondent employees Iiled a

Complaint beIore the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC)

Regional Arbitration Branch No. III and sued SME Bank, spouses Abelardo

and Olga Samson and Aurelio VillaIlor (the Samson Group) Ior unIair labor

practice; illegal dismissal; illegal deductions; underpayment; and

nonpayment oI allowances, separation pay and 13

th

month pay.

28

Subsequently, they amended their Complaint to include Agustin and De

Guzman as respondents to the case.

29

On 27 October 2004, the labor arbiter ruled that the buyer oI an

enterprise is not bound to absorb its employees, unless there is an express

stipulation to the contrary. However, he also Iound that respondent

employees were illegally dismissed, because they had involuntarily executed

their resignation letters aIter relying on representations that they would be

given their separation beneIits and rehired by the new management.

Accordingly, the labor arbiter decided the case against Agustin and De

Guzman, but dismissed the Complaint against the Samson Group, as

Iollows:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, judgment is hereby

rendered ordering respondents Eduardo Agustin, Jr. and Peregrin De

Guzman to pay complainants` separation pay in the total amount oI

##$%&'#('' detailed as Iollows:

)*+,-.+/ 1( 23453. 6 7%8#9(''

:+,3.;/ 1( 23453.% ".( 6 <<%=9&(''

>+?-.3@/ 1( A3BC/?3 6 =&%D'9(''

E+;-* )( )45+.+@F 6 D$%<87(''

G+H-/B 1( )45+.+@F% ".( 6 D=%'''(''

)FI-H+3 )( :/4-@- 6 D'D%7<'(''

All other claims including the complaint against Abelardo Samson,

Olga Samson and Aurelio VillaIlor are hereby DISMISSED Ior want oI

merit.

SO ORDERED.

30

26

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), p. 149; Undated Sinumpaang Salaysay oI Simeon B. Espiritu, Jr.

27

Id.

28

Rollo (G.R. No. 184517), pp. 200-221; Labor Arbiter`s Decision dated 27 October 2004, penned by

Labor Arbiter Henry D. Isorena.

29

Id. at 129-140; Amended Complaints dated 23 October 2002.

30

Id. at 221.

Decision 5 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

DissatisIied with the Decision oI the labor arbiter, respondent

employees, Agustin and De Guzman brought separate appeals to the NLRC.

Respondent employees questioned the labor arbiter`s Iailure to award

backwages, while Agustin and De Guzman contended that they should not

be held liable Ior the payment oI the employees` claims.

The NLRC Iound that there was only a mere transIer oI shares and

thereIore, a mere change oI management Irom Agustin and De Guzman to

the Samson Group. As the change oI management was not a valid ground to

terminate respondent bank employees, the NLRC ruled that they had indeed

been illegally dismissed. It Iurther ruled that Agustin, De Guzman and the

Samson Group should be held jointly and severally liable Ior the employees`

separation pay and backwages, as Iollows:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the Decision appealed Irom

is hereby MODIFIED. Respondents are hereby Ordered to jointly and

severally pay the complainants backwages Irom 11 September 2001 until

the Iinality oI this Decision, separation pay at one month pay Ior every

year oI service, 10,000.00 and 5,000.00 moral and exemplary damages,

and Iive (5) percent attorney`s Iees.

Other dispositions are AFFIRMED

SO ORDERED.

31

On 28 November 2006, the NLRC denied the Motions Ior

Reconsideration Iiled by Agustin, De Guzman and the Samson Group.

32

Agustin and De Guzman Iiled a Rule 65 Petition Ior Certiorari with

the CA, docketed as CA-G.R. SP No. 97510. The Samson Group likewise

Iiled a separate Rule 65 Petition Ior Certiorari with the CA, docketed as

CA-G.R. SP No. 97942. Motions to consolidate both cases were not acted

upon by the appellate court.

On 13 March 2008, the CA rendered a Decision in CA-G.R. SP No.

97510 aIIirming that oI the NLRC. The fallo oI the CA Decision reads:

WHEREFORE, in view oI the Ioregoing, the petition is

DENIED. Accordingly, the Decision dated May 8, 2006, and Resolution

dated November 28, 2006 oI the National Labor Relations Commission in

NLRC NCR CA No. 043236-05 (NLRC RAB III-07-4542-02) are hereby

AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.

33

31

Id. at 334-342; NLRC Decision dated 8 May 2006, penned by Commissioner Angelita A. Gacutan and

concurred in by Presiding Commissioner Raul T. Aquino. Commissioner Victoriano R. Calaycay was on

leave.

32

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), pp. 112-113.

33

Rollo (G.R. No. 184517), pp. 70-71; CA Decision dated 13 March 2008.

Decision 6 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

Subsequently, CA-G.R. SP No. 97942 was disposed oI by the

appellate court in a Decision dated 15 January 2008, which likewise

aIIirmed that oI the NLRC. The dispositive portion oI the CA Decision

states:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the instant Petition Ior

Certiorari is denied, and the herein assailed May 8, 2006 Decision and

November 28, 2006 Resolution oI the NLRC are hereby AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.

34

The appellate court denied the Motions Ior Reconsideration Iiled by

the parties in Resolutions dated 1 September 2008

35

and 19 February 2009.

36

The Samson Group then Iiled two separate Rule 45 Petitions

questioning the CA Decisions and Resolutions in CA-G.R. SP No. 97510 and

CA-G.R. SP No. 97942. On 17 June 2009, this Court resolved to consolidate

both Petitions.

37

THE ISSUES

Succinctly, the parties are asking this Court to determine whether

respondent employees were illegally dismissed and, iI so, which oI the

parties are liable Ior the claims oI the employees and the extent oI the relieIs

that may be awarded to these employees.

THE COURTS RULING

The instant Petitions are partly meritorious.

I

Respondent employees were illegally dismissed.

J4 @/ )*+,-.+/ 23453.% :+,3.;/

23453.% ".(% E+;-* )45+.+@F% )FI-H+3

:/4-@- 3B; >+?-.3@/ A3BC/?3

The Samson Group contends that Elicerio, Ricardo, Fidel, and

Liberato voluntarily resigned Irom their posts, while EuIemia retired Irom

her position. As their resignations and retirements were voluntary, they were

not dismissed Irom their employment.

38

In support oI this argument, it

34

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), p. 66.

35

Rollo (G.R. No. 184517), pp. 73-74.

36

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), p. 68-69.

37

Rollo (G.R. No. 184517), p. 623.

38

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), pp. 39-40; Petition dated 10 March 2009.

Decision 7 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

presented copies oI their resignation and retirement letters,

39

which were

couched in terms oI gratitude.

We disagree. While resignation letters containing words oI gratitude

may indicate that the employees were not coerced into resignation,

40

this Iact

alone is not conclusive prooI that they intelligently, Ireely and voluntarily

resigned. To rule that resignation letters couched in terms oI gratitude are, by

themselves, conclusive prooI that the employees intended to relinquish their

posts would open the Iloodgates to possible abuse. In order to withstand the

test oI validity, resignations must be made voluntarily and with the intention

oI relinquishing the oIIice, coupled with an act oI relinquishment.

41

ThereIore, in order to determine whether the employees truly intended to

resign Irom their respective posts, we cannot merely rely on the tenor oI the

resignation letters, but must take into consideration the totality oI

circumstances in each particular case.

Here, the records show that Elicerio, Ricardo, Fidel, and Liberato only

tendered resignation letters because they were led to believe that, upon

reapplication, they would be reemployed by the new management.

42

As it

turned out, except Ior Simeon, Jr., they were not rehired by the new

management. Their reliance on the representation that they would be

reemployed gives credence to their argument that they merely submitted

courtesy resignation letters because it was demanded oI them, and that they

had no real intention oI leaving their posts. We thereIore conclude that

Elicerio, Ricardo, Fidel, and Liberato did not voluntarily resign Irom their

work; rather, they were terminated Irom their employment.

As to EuIemia, both the CA and the NLRC discussed her case together

with the cases oI the rest oI respondent-employees. However, a review oI the

records shows that, unlike her co-employees, she did not resign; rather, she

submitted a letter indicating that she was retiring Irom her Iormer position.

43

The Iact that EuIemia retired and did not resign, however, does not

change our conclusion that illegal dismissal took place.

Retirement, like resignation, should be an act completely voluntary on

the part oI the employee. II the intent to retire is not clearly established or iI

the retirement is involuntary, it is to be treated as a discharge.

44

39

Rollo (G.R. No. 184517), pp. 545-550; Resignation letters oI Elicerio Gaspar, Ricardo M. Gaspar, Jr.,

Fidel E. Espiritu, and Liberato B. Mangoba, all dated 27 August 2001; Retirement letter oI EuIemia E.

Rosete dated 'September 2001.

40

Globe Telecom v. Crisologo, 556 Phil. 643, 652 (2007); St. Michael Academy v. NLRC, 354 Phil. 491, 509

(1998).

41

Magtoto v. NLRC, 224 Phil. 210, 222-223 (1985), citing Patten v. Miller, 190 Ga. 123, 8 S.E. 2nd 757,

770; Sadler v. Jester, D.C. Tex., 46 F. Supp. 737, 740; and Black's Law Dictionary (Revised Fourth Edition,

1968).

42

Rollo (G.R. No. 184517), pp. 202-204; Labor Arbiter`s Decision dated 27 October 2004

43

Id. at 549; Retirement letter oI EuIemia E. Rosete dated 'September 2001.

44

De Leon v. NLRC, 188 Phil. 666 (1980).

Decision 8 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

In this case, the Iacts show that EuIemia`s retirement was not oI her

own volition. The circumstances could not be more telling. The Iacts show

that EuIemia was likewise given the option to resign or retire in order to

IulIill the precondition in the Letter Agreements that the seller should

'terminate/retire the employees |mutually agreed upon| upon transIer oI

shares to the buyers.

45

Thus, like her other co-employees, she Iirst

submitted a letter oI resignation dated 27 August 2001.

46

For one reason or

another, instead oI resigning, she chose to retire and submitted a retirement

letter to that eIIect.

47

It was this letter that was subsequently transmitted to

the representative oI the Samson Group on 11 September 2001.

48

In San Miguel Corporation v. NLRC,

49

we have explained that

involuntary retirement is tantamount to dismissal, as employees can only

choose the means and methods oI terminating their employment, but are

powerless as to the status oI their employment and have no choice but to

leave the company. This rule squarely applies to EuIemia`s case. Indeed, she

could only choose between resignation and retirement, but was made to

understand that she had no choice but to leave SME Bank. Thus, we

conclude that, similar to her other co-employees, she was illegally dismissed

Irom employment.

The Samson Group Iurther argues

50

that, assuming the employees

were dismissed, the dismissal is legal because cessation oI operations due to

serious business losses is one oI the authorized causes oI termination under

Article 283 oI the Labor Code.

51

Again, we disagree.

The law permits an employer to dismiss its employees in the event oI

closure oI the business establishment.

52

However, the employer is required

to serve written notices on the worker and the Department oI Labor at least

one month beIore the intended date oI closure.

53

Moreover, the dismissed

employees are entitled to separation pay, except iI the closure was due to

serious business losses or Iinancial reverses.

54

However, to be exempt Irom

45

Rollo (G.R. No. 184517), pp. 120, 122; Letter Agreements.

46

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), p. 138; Resignation letter oI EuIemia E. Rosete dated 27 August 2001.

47

Id. at 171; Retirement letter oI EuIemia E. Rosete dated 'September , 2001.

48

Id. at 141.

49

354 Phil. 815 (1998).

50

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), p. 37; Petition dated 10 March 2009.

51

Art. 283. Closure of Establishment and Reduction of Personnel. The employer may also terminate the

employment oI any employee due to the installation oI labor-saving devices, redundancy, retrenchment to

prevent losses or the closing or cessation oI operation oI the establishment or undertaking unless the

closing is Ior the purpose oI circumventing the provisions oI this Title, by serving a written notice on the

worker and the Ministry oI Labor and Employment at least one (1) month beIore the intended date thereoI.

x x x.

52

LABOR CODE, Art. 283.

53

Id.

54

Id.; North Davao Mining Corporation v. NLRC, 325 Phil. 202, 209 (1996).

Decision 9 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

making such payment, the employer must justiIy the closure by presenting

convincing evidence that it actually suIIered serious Iinancial reverses.

55

In this case, the records do not support the contention oI SME Bank

that it intended to close the business establishment. On the contrary, the

intention oI the parties to keep it in operation is conIirmed by the provisions

oI the Letter Agreements requiring Agustin and De Guzman to guarantee the

'peaceIul transition oI management oI the bank and to appoint 'a manager

oI |the Samson Group`s| choice x x x to oversee bank operations.

Even assuming that the parties intended to close the bank, the records

do not show that the employees and the Department oI Labor were given

written notices at least one month beIore the dismissal took place. Moreover,

aside Irom their bare assertions, the parties Iailed to substantiate their claim

that SME Bank was suIIering Irom serious Iinancial reverses.

In Iine, the argument that the dismissal was due to an authorized cause

holds no water.

Petitioner bank also argues that, there being a transIer oI the business

establishment, the innocent transIerees no longer have any obligation to

continue employing respondent employees,

56

and that the most that they can

do is to give preIerence to the qualiIied separated employees; hence, the

employees were validly dismissed.

57

The argument is misleading and unmeritorious. Contrary to petitioner

bank`s argument, there was no transfer of the business establishment to

speak of, but merely a change in the new majority shareholders of the

corporation.

There are two types oI corporate acquisitions: asset sales and stock

sales.

58

In asset sales, the corporate entity

59

sells all or substantially all oI its

assets

60

to another entity. In stock sales, the individual or corporate

shareholders

61

sell a controlling block oI stock

62

to new or existing

shareholders.

In asset sales, the rule is that the seller in good Iaith is authorized to

dismiss the aIIected employees, but is liable Ior the payment oI separation

55

Indino v. NLRC, 258 Phil. 792, 799 (1989).

56

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), p. 4; Petition dated 10 March 2009.

57

Id. at 30.

58

DALE A. OESTERLE, THE LAW OF MERGERS, ACQUISITIONS AND REORGANIZATIONS, 35 (1991).

59

Id.

60

Id. at 39.

61

Id. at 35.

62

Id. at 39.

Decision 10 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

pay under the law.

63

The buyer in good Iaith, on the other hand, is not

obliged to absorb the employees aIIected by the sale, nor is it liable Ior the

payment oI their claims.

64

The most that it may do, Ior reasons oI public

policy and social justice, is to give preIerence to the qualiIied separated

personnel oI the selling Iirm.

65

In contrast with asset sales, in which the assets oI the selling

corporation are transIerred to another entity, the transaction in stock sales

takes place at the shareholder level. Because the corporation possesses a

personality separate and distinct Irom that oI its shareholders, a shiIt in the

composition oI its shareholders will not aIIect its existence and continuity.

Thus, notwithstanding the stock sale, the corporation continues to be the

employer oI its people and continues to be liable Ior the payment oI their

just claims. Furthermore, the corporation or its new majority shareholders

are not entitled to lawIully dismiss corporate employees absent a just or

authorized cause.

In the case at bar, the Letter Agreements show that their main object is

the acquisition by the Samson Group oI 86.365 oI the shares oI stock oI

SME Bank.

66

Hence, this case involves a stock sale, whereby the transIeree

acquires the controlling shares oI stock oI the corporation. Thus, Iollowing

the rule in stock sales, respondent employees may not be dismissed except

Ior just or authorized causes under the Labor Code.

Petitioner bank argues that, Iollowing our ruling in Manlimos v.

NLRC,

67

even in cases oI stock sales, the new owners are under no legal duty

to absorb the seller`s employees, and that the most that the new owners may

do is to give preIerence to the qualiIied separated employees.

68

Thus,

petitioner bank argues that the dismissal was lawIul.

We are not persuaded.

Manlimos dealt with a stock sale in which a new owner or

management group acquired complete ownership oI the corporation at the

shareholder level.

69

The employees oI the corporation were later 'considered

terminated, with their conIormity

70

by the new majority shareholders. The

employees then re-applied Ior their jobs and were rehired on a probationary

basis. AIter about six months, the new management dismissed two oI the

employees Ior having abandoned their work, and it dismissed the rest Ior

63

Central Azucarera del Danao v. Court of Appeals, 221 Phil. 647 (1985).

64

Id.

65

Id.

66

Rollo (G.R. No. 184517), pp. 120, 122; Letter Agreements.

67

312 Phil. 178 (1995).

68

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), p. 29; Petition dated 10 March 2009.

69

Manlimos v. NLRC, supra note 67.

70

Id. at 183.

Decision 11 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

committing 'acts prejudicial to the interest oI the new management.

71

ThereaIter, the employees sought reinstatement, arguing that their dismissal

was illegal, since they 'remained regular employees oI the corporation

regardless oI the change oI management.

72

In disposing oI the merits oI the case, we upheld the validity oI the

second termination, ruling that 'the parties are Iree to renew the contract or

not |upon the expiration oI the period provided Ior in their probationary

contract oI employment|.

73

Citing our pronouncements in Central

Azucarera del Danao v. Court of Appeals,

74

San Felipe Neri School of

Mandaluyong, Inc. v. NLRC,

75

and MDII Supervisors & Confidential

Employees Association v. Presidential Assistant on Legal Affairs,

76

we

likewise upheld the validity oI the employees` Iirst separation Irom

employment, pronouncing as Iollows:

A change oI ownership in a business concern is not proscribed by

law. In Central Azucarera del Danao vs. Court of Appeals, this Court

stated:

There can be no controversy Ior it is a principle well-

recognized, that it is within the employer`s legitimate

sphere oI management control oI the business to adopt

economic policies or make some changes or adjustments in

their organization or operations that would insure proIit to

itselI or protect the investment oI its stockholders. As in the

exercise oI such management prerogative, the employer

may merge or consolidate its business with another, or sell

or dispose all or substantially all oI its assets and properties

which may bring about the dismissal or termination oI its

employees in the process. Such dismissal or termination

should not however be interpreted in such a manner as to

permit the employer to escape payment oI termination pay.

For such a situation is not envisioned in the law. It strikes at

the very concept oI social justice.

In a number oI cases on this point, the rule has been laid

down that the sale or disposition must be motivated by

good Iaith as an element oI exemption Irom liability.

Indeed, an innocent transIeree oI a business establishment

has no liability to the employees oI the transIer or to

continue employer them. Nor is the transIeree liable Ior

past unIair labor practices oI the previous owner, except,

when the liability thereIor is assumed by the new employer

under the contract oI sale, or when liability arises because

oI the new owner`s participation in thwarting or deIeating

the rights oI the employees.

71

Id. at 184.

72

Id. at 185.

73

Id. at 192.

74

Supra note 63, at 190-191.

75

278 Phil. 484 (1991).

76

169 Phil. 42 (1977).

Decision 12 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

Where such transIer oI ownership is in good Iaith, the transIeree is

under no legal duty to absorb the transIeror`s employees as there is no law

compelling such absorption. The most that the transIeree may do, Ior

reasons oI public policy and social justice, is to give preIerence to the

qualiIied separated employees in the Iilling oI vacancies in the Iacilities oI

the purchaser.

Since the petitioners were eIIectively separated Irom work due to a

bona fide change oI ownership and they were accordingly paid their

separation pay, which they Ireely and voluntarily accepted, the private

respondent corporation was under no obligation to employ them; it may,

however, give them preIerence in the hiring. x x x. (Citations omitted)

We take this opportunity to revisit our ruling in Manlimos insoIar as it

applied a doctrine on asset sales to a stock sale case. Central Azucarera del

Danao, San Felipe Neri School of Mandaluyong and MDII Supervisors &

Confidential Employees Association all dealt with asset sales, as they

involved a sale oI all or substantially all oI the assets oI the corporation. The

transactions in those cases were not made at the shareholder level, but at the

corporate level. Thus, applicable to those cases were the rules in asset sales:

the employees may be separated Irom their employment, but the seller is

liable Ior the payment oI separation pay; on the other hand, the buyer in

good Iaith is not required to retain the aIIected employees in its service, nor

is it liable Ior the payment oI their claims.

The rule should be diIIerent in Manlimos, as this case involves a stock

sale. It is error to even discuss transIer oI ownership oI the business, as the

business did not actually change hands. The transIer only involved a change

in the equity composition oI the corporation. To reiterate, the employees are

not transferred to a new employer, but remain with the original

corporate employer, notwithstanding an equity shift in its majority

shareholders. This being so, the employment status oI the employees

should not have been aIIected by the stock sale. A change in the equity

composition oI the corporate shareholders should not result in the automatic

termination oI the employment oI the corporation`s employees. Neither

should it give the new majority shareholders the right to legally dismiss the

corporation`s employees, absent a just or authorized cause.

The right to security oI tenure guarantees the right oI employees to

continue in their employment absent a just or authorized cause Ior

termination. This guarantee proscribes a situation in which the corporation

procures the severance oI the employment oI its employees who patently

still desire to work Ior the corporation only because new majority

stockholders and a new management have come into the picture. This

situation is a clear circumvention oI the employees` constitutionally

guaranteed right to security oI tenure, an act that cannot be countenanced by

this Court.

Decision 13 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

It is thus erroneous on the part oI the corporation to consider the

employees as terminated Irom their employment when the sole reason Ior so

doing is a change oI management by reason oI the stock sale. The

conIormity oI the employees to the corporation`s act oI considering them as

terminated and their subsequent acceptance oI separation pay does not

remove the taint oI illegal dismissal. Acceptance oI separation pay does not

bar the employees Irom subsequently contesting the legality oI their

dismissal, nor does it estop them Irom challenging the legality oI their

separation Irom the service.

77

We thereIore see it Iit to expressly reverse our ruling in Manlimos

insoIar as it upheld that, in a stock sale, the buyer in good Iaith has no

obligation to retain the employees oI the selling corporation; and that the

dismissal oI the aIIected employees is lawIul, even absent a just or

authorized cause.

J4 @/ G+H-/B )45+.+@F% ".(

The CA and the NLRC discussed the case oI Simeon, Jr. together with

that oI the rest oI respondent-employees. However, a review oI the records

shows that the conditions leading to his dismissal Irom employment are

diIIerent. We thus discuss his circumstance separately.

The Samson Group contends that Simeon, Jr., likewise voluntarily

resigned Irom his post.

78

According to them, he had resigned Irom SME

Bank beIore the share transIer took place.

79

Upon the change oI ownership

oI the shares and the management oI the company, Simeon, Jr. submitted a

letter oI application to and was rehired by the new management.

80

However,

the Samson Group alleged that Ior purely personal reasons, he again

resigned Irom his employment on 15 October 2001.

81

Simeon, Jr., on the other hand, contends that while he was reappointed

by the new management aIter his letter oI application was transmitted, he

was not given a clear position, his beneIits were reduced, and he suIIered a

demotion in rank.

82

These allegations were not reIuted by the Samson

Group.

We hold that Simeon, Jr. was likewise illegally dismissed Irom his

employment.

77

Sari-sari Group of Companies, Inc. v. Piglas Kamao, G.R. No. 164624, 11 August 2008, 561 SCRA 569.

78

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), p. 11; Petition dated 10 March 2009.

79

Id. at 139; Resignation Letter oI Simeon B. Espiritu, Jr. dated 27 August 2001.

80

Id.

81

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), p. 139; Resignation Letter oI Simeon B. Espiritu, Jr. eIIective 15 October 2001.

82

Id. at 149; Undated Sinumpaang Salaysay oI Simeon B. Espiritu, Jr.

Decision 14 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

Similar to our earlier discussion, we Iind that his Iirst courtesy

resignation letter was also executed involuntarily. Thus, it cannot be the

basis oI a valid resignation; and thus, at that point, he was illegally

terminated Irom his employment. He was, however, rehired by SME Bank

under new management, although based on his allegations, he was not

reinstated to his Iormer position or to a substantially equivalent one.

83

Rather, he even suIIered a reduction in beneIits and a demotion in rank.

84

These led to his submission oI another resignation letter eIIective 15 October

2001.

85

We rule that these circumstances show that Simeon, Jr. was

constructively dismissed. In Peaflor v. Outdoor Clothing Manufacturing

Corporation,

86

we have deIined constructive dismissal as Iollows:

Constructive dismissal is an involuntary resignation by the employee due

to the harsh, hostile, and unIavorable conditions set by the employer and

which arises when a clear discrimination, insensibility, or disdain by an

employer exists and has become unbearable to the employee.

87

Constructive dismissal exists where there is cessation oI work,

because 'continued employment is rendered impossible, unreasonable or

unlikely, as an oIIer involving a demotion in rank or a diminution in pay

and other beneIits.

88

These circumstances are clearly availing in Simeon, Jr.`s case. He was

made to resign, then rehired under conditions that were substantially less

than what he was enjoying beIore the illegal termination occurred. Thus, Ior

the second time, he involuntarily resigned Irom his employment. Clearly,

this case is illustrative oI constructive dismissal, an act prohibited under our

labor laws.

II

SME Bank, Eduardo M. Agustin, Jr. and Peregrin de

Guzman, Jr. are liable for illegal dismissal.

Having ruled on the illegality oI the dismissal, we now discuss the

issue oI liability and determine who among the parties are liable Ior the

claims oI the illegally dismissed employees.

83

Id.

84

Id.

85

Id. at 139; Resignation Letter oI Simeon B. Espiritu, Jr. eIIective 15 October 2001.

86

G.R. No. 177114, 13 April 2010, 618 SCRA 208.

87

Id.

88

Verdadero v. Barney Autolines Group of Companies Transport, Inc., G.R. No. 195428, 29 August 2012,

679 SCRA 545, 555.

Decision 15 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

The settled rule is that an employer who terminates the employment oI

its employees without lawIul cause or due process oI law is liable Ior illegal

dismissal.

89

None oI the parties dispute that SME Bank was the employer oI

respondent employees. The Iact that there was a change in the composition

oI its shareholders did not aIIect the employer-employee relationship

between the employees and the corporation, because an equity transIer

aIIects neither the existence nor the liabilities oI a corporation. Thus, SME

Bank continued to be the employer oI respondent employees

notwithstanding the equity change in the corporation. This outcome is in line

with the rule that a corporation has a personality separate and distinct Irom

that oI its individual shareholders or members, such that a change in the

composition oI its shareholders or members would not aIIect its corporate

liabilities.

ThereIore, we conclude that, as the employer oI the illegally dismissed

employees beIore and aIter the equity transIer, petitioner SME Bank is liable

Ior the satisIaction oI their claims.

Turning now to the liability oI Agustin, De Guzman and the Samson

Group Ior illegal dismissal, at the outset we point out that there is no privity

oI employment contracts between Agustin, De Guzman and the Samson

Group, on the one hand, and respondent employees on the other. Rather, the

employment contracts were between SME Bank and the employees.

However, this Iact does not mean that Agustin, De Guzman and the Samson

Group may not be held liable Ior illegal dismissal as corporate directors or

oIIicers. In Bogo-Medellin Sugarcane Planters Association, Inc. v. NLRC,

90

we laid down the rule as regards the liability oI corporate directors and

oIIicers in illegal dismissal cases, as Iollows:

Unless they have exceeded their authority, corporate oIIicers are, as a

general rule, not personally liable Ior their oIIicial acts, because a

corporation, by legal Iiction, has a personality separate and distinct Irom

its oIIicers, stockholders and members. However, this Iictional veil may be

pierced whenever the corporate personality is used as a means oI

perpetuating a Iraud or an illegal act, evading an existing obligation, or

conIusing a legitimate issue. In cases oI illegal dismissal, corporate

directors and oIIicers are solidarily liable with the corporation, where

terminations oI employment are done with malice or in bad Iaith.

91

(Citations omitted)

89

Lambert Pawnbrokers and Jewelry Corp. v. Binamira, G.R. No. 170464, 12 July 2010, 624 SCRA 705,

708.

90

357 Phil. 110 (1998).

91

Id. at 127.

Decision 16 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

Thus, in order to determine the respective liabilities oI Agustin, De

Guzman and the Samson Group under the aIore-quoted rule, we must

determine, first, whether they may be considered as corporate directors or

oIIicers; and, second, whether the terminations were done maliciously or in

bad Iaith.

There is no question that both Agustin and De Guzman were corporate

directors oI SME Bank. An analysis oI the Iacts likewise reveals that the

dismissal oI the employees was done in bad Iaith. Motivated by their desire

to dispose oI their shares oI stock to Samson, they agreed to and later

implemented the precondition in the Letter Agreements as to the termination

or retirement oI SME Bank`s employees. However, instead oI going through

the proper procedure, the bank manager induced respondent employees to

resign or retire Irom their respective employments, while promising that they

would be rehired by the new management. Fully relying on that promise,

they tendered courtesy resignations or retirements and eventually Iound

themselves jobless. Clearly, this sequence oI events constituted a gross

circumvention oI our labor laws and a violation oI the employees`

constitutionally guaranteed right to security oI tenure. We thereIore rule that,

as Agustin and De Guzman are corporate directors who have acted in bad

Iaith, they may be held solidarily liable with SME Bank Ior the satisIaction

oI the employees` lawIul claims.

As to spouses Samson, we Iind that nowhere in the records does it

appear that they were either corporate directors or oIIicers oI SME Bank at

the time the illegal termination occurred, except that the Samson Group had

already taken over as new management when Simeon, Jr. was constructively

dismissed. Not being corporate directors or oIIicers, spouses Samson were

not in legal control oI the bank and consequently had no power to dismiss its

employees.

Respondent employees argue that the Samson Group had already

taken over and conducted an inventory beIore the execution oI the share

purchase agreement.

92

Agustin and De Guzman likewise argued that it was at

Olga Samson`s behest that the employees were required to resign Irom their

posts.

93

Even iI this statement were true, it cannot amount to a Iinding that

spouses Samson should be treated as corporate directors or oIIicers oI SME

Bank. The records show that it was Espiritu who asked the employees to

tender their resignation and or retirement letters, and that these letters were

actually tendered to him.

94

He then transmitted these letters to the

representative oI the Samson Group.

95

That the spouses Samson had to ask

Espiritu to require the employees to resign shows that they were not in

control oI the corporation, and that the Iormer shareholders through

92

Rollo (G.R. No. 184517), p. 441; Comment (To the Petition Ior Certiorari dated 14 February 2007) dated

20 April 2007.

93

Id. at 396; Comment (re: Petition Ior Review under Rule 45) dated 19 December 2008.

94

Rollo (G.R. No. 186641), pp. 134-140.

95

Id. at 141; Letter dated 11 September 2001.

Decision 17 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

Espiritu were still in charge thereoI. As the spouses Samson were neither

corporate oIIicers nor directors at the time the illegal dismissal took place,

we Iind that there is no legal basis in the present case to hold them in their

personal capacities solidarily liable with SME Bank Ior illegally dismissing

respondent employees, without prejudice to any liabilities that may have

attached under other provisions oI law.

Furthermore, even iI spouses Samson were already in control oI the

corporation at the time that Simeon, Jr. was constructively dismissed, we

reIuse to pierce the corporate veil and Iind them liable in their individual

steads. There is no showing that his constructive dismissal amounted to

more than a corporate act by SME Bank, or that spouses Samson acted

maliciously or in bad Iaith in bringing about his constructive dismissal.

Finally, as regards Aurelio VillaIlor, while he may be considered as a

corporate oIIicer, being the president oI SME Bank, the records are bereIt oI

any evidence that indicates his actual participation in the termination oI

respondent employees. Not having participated at all in the illegal act, he

may not be held individually liable Ior the satisIaction oI their claims.

III

Respondent employees are entitled to separation pay, full

backwages, moral damages, exemplary damages and

attorneys fees.

The rule is that illegally dismissed employees are entitled to (1) either

reinstatement, iI viable, or separation pay iI reinstatement is no longer

viable; and (2) backwages.

96

Courts may grant separation pay in lieu oI reinstatement when the

relations between the employer and the employee have been so severely

strained; when reinstatement is not in the best interest oI the parties; when it

is no longer advisable or practical to order reinstatement; or when the

employee decides not to be reinstated.

97

In this case, respondent employees

expressly pray Ior a grant oI separation pay in lieu oI reinstatement. Thus,

Iollowing a Iinding oI illegal dismissal, we rule that they are entitled to the

payment oI separation pay equivalent to their one-month salary Ior every

year oI service as an alternative to reinstatement.

Respondent employees are likewise entitled to Iull backwages

notwithstanding the grant oI separation pay. In Santos v. NLRC,

98

we

explained that an award oI backwages restores the income that was lost by

96

Robinsons Galleria/Robinsons Supermarket Corporation v. Ranchez, G.R. No. 177937, 19 January 2011,

640 SCRA 135, 144.

97

DUP Sound Phils. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 168317, 21 November 2011, 660 SCRA 461, 473.

98

238 Phil. 161 (1987).

Decision 18 GR. Nos. 184517 and 186641

reason of the unlawful dismissal, while separation pay "provide[ s] the

employee with 'the wherewithal during the period that he is looking for

I

' lJ

9

} . . b . 1 fi

another emp oyment. " T ms, separatiOn pay 1s a proper su stltute on y or

reinstatement; it is not an adequate substitute for both reinstatement and

backwages.

100

Hence, respondent employees are entitled to the grant of full

backwages in addition to separation pay.

As to moral damages, exemplary damages and attorney's fees, we

uphold the appellate court's grant thereof based on our finding that the

forced resignations and retirement were fraudulently done and attended by

bad faith.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the instant Petitions for

Review are PARTIALLY GRANTED.

The assailed Decision and Resolution of the Court of Appeals in CA-

G.R. SP No. 97510 dated 13 March 2008 and 1 September 2008,

respectively, are hereby REVERSED and SET ASIDE insofar as it held

Abelardo P. Samson, Olga Samson and Aurelio Villaflor, Jr. solidarily

liable for illegal dismissal.

The assailed Decision and Resolution of the Court of Appeals in

CA-G.R. SP No. 97942 dated 15 January 2008 and 19 February 2009,

respectively, are likewise REVERSED and SET ASIDE insofar as it held

Abelardo P. Samson, Olga Samson and Aurelio Villaflor, Jr. solidarily

liable for illegal dismissal.

We REVERSE our ruling in Manlimos v. NLRC insofar as it upheld

thai, in a stock sale, the buyer in good faith has no obligation to retain the

employees of the selling corporation, and that the dismissal of the affected

employees is lawful even absent a just or authorized cause.

SO ORDERED.

99

ld. at 167.

IOU fd.

MARIA LOURDES P. A. SERENO

Chief Justice

Decision

WE CONCUR:

Associate Justice

Associate Justice

(No part)

MARIANO C. DEL CASTILLO

Associate Justice

(On leave)

MARTIN S. VILLARAMA, JR.

Associate Justice

1(/p

JOSE CATRAL MENllozA

Associate Justice

ESTELA 1\t[ )>ERLAS-BERNABE

Associate Justice

19 GR. Nos. 184517 and 186641

Associate Justice

ROBERTO A. ABAD

Associate Justice

16vENIDO L. REYES

Associate Justice

Associate Justice

Decision 20 G.R. Nos. 184517 and 186641

CERTIFICATION

Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution, I certify that

the conclusions in the above Decision had been reached in consultation

before the case was assigned to the writer of the opinion of the Court.

MARIA LOURDES P. A. SERENO

Chief Justice

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Jose Ferreira Criminal ComplaintDocument4 paginiJose Ferreira Criminal ComplaintDavid Lohr100% (1)

- SMART Goal Worksheet (Action Plan)Document2 paginiSMART Goal Worksheet (Action Plan)Tiaan de Jager100% (1)

- UntitledDocument256 paginiUntitledErick RomeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- U.S. v. Sun Myung Moon 718 F.2d 1210 (1983)De la EverandU.S. v. Sun Myung Moon 718 F.2d 1210 (1983)Încă nu există evaluări

- Remedial Law PDFDocument14 paginiRemedial Law PDFThe Supreme Court Public Information Office100% (1)

- UP Civil ProcedureDocument116 paginiUP Civil ProcedureRoberts Sam100% (3)

- Sam Legal MemorandumDocument6 paginiSam Legal MemorandumRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- SME Bank Inc V de Guzman GR 184517 & 186641Document19 paginiSME Bank Inc V de Guzman GR 184517 & 186641Charmaine MejiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modern Advanced Accounting in Canada Canadian 8th Edition Hilton Solutions Manual PDFDocument106 paginiModern Advanced Accounting in Canada Canadian 8th Edition Hilton Solutions Manual PDFa748358425Încă nu există evaluări

- Garcia Fule vs. CADocument2 paginiGarcia Fule vs. CARoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- B16. Project Employment - Bajaro vs. Metro Stonerich Corp.Document5 paginiB16. Project Employment - Bajaro vs. Metro Stonerich Corp.Lojo PiloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sme Bank Inc v. de Guzman G.R. No. 184517Document3 paginiSme Bank Inc v. de Guzman G.R. No. 184517abbyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Concerning The Temple of Preah Vihear - Cambodia v. ThailandDocument3 paginiCase Concerning The Temple of Preah Vihear - Cambodia v. ThailandRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sandejas v. Ignacio, Jr. - CaseDocument8 paginiSandejas v. Ignacio, Jr. - CaseRobeh AtudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Suez CanalDocument7 paginiSuez CanalUlaş GüllenoğluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Embassy Farms Vs CADocument12 paginiEmbassy Farms Vs CADexter CircaÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. 206666Document14 paginiG.R. No. 206666AliyahDazaSandersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petitioners Vs Vs Respondents: en BancDocument16 paginiPetitioners Vs Vs Respondents: en BancAizaLizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SME Bank, Inc. v. de GuzmanDocument16 paginiSME Bank, Inc. v. de GuzmanKrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Termination CasesDocument47 paginiTermination CasesSheilah Mae PadallaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SME V de Guzman G.R. No. 184517, October 08, 2013Document19 paginiSME V de Guzman G.R. No. 184517, October 08, 2013ChatÎncă nu există evaluări

- 25-Guillermo v. UsonDocument12 pagini25-Guillermo v. UsonRogelio BataclanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gomez vs. GomezDocument33 paginiGomez vs. GomezbreeH20Încă nu există evaluări

- Labor Digest and TerminationDocument33 paginiLabor Digest and TerminationTJ HarrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civpro Addvitional CasesDocument78 paginiCivpro Addvitional CasesGabrielAblolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gomez vs. GomezDocument35 paginiGomez vs. GomezJacob John JoshuaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petitioner vs. VS.: First DivisionDocument9 paginiPetitioner vs. VS.: First DivisionMaureen AntallanÎncă nu există evaluări

- EstafaDocument158 paginiEstafaMelvin PernezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Estafa, BP 22Document68 paginiEstafa, BP 22Marry SuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching Prof. PresentationDocument50 paginiTeaching Prof. Presentationloric callosÎncă nu există evaluări

- En Banc: Abakada Guro Party List (Formerly Aasjas) Officers Samson S. Alcantara and ED Vincent S. AlbanoDocument78 paginiEn Banc: Abakada Guro Party List (Formerly Aasjas) Officers Samson S. Alcantara and ED Vincent S. Albanoshirlyn cuyongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ambray vs. TsourousDocument12 paginiAmbray vs. TsourousDexter CircaÎncă nu există evaluări

- $ Upreme Qcourt: L/Epublic of Tbe ManilaDocument11 pagini$ Upreme Qcourt: L/Epublic of Tbe ManilaMarkÎncă nu există evaluări

- BP22 (PDL) Ambito vs. People (SC)Document26 paginiBP22 (PDL) Ambito vs. People (SC)bbysheÎncă nu există evaluări

- 175277Document16 pagini175277The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 116739-2007-Gomez - v. - Gomez-Samson20181022-5466-kbx1y PDFDocument30 pagini116739-2007-Gomez - v. - Gomez-Samson20181022-5466-kbx1y PDFCamille CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Estafa, BP 22Document67 pagini4 Estafa, BP 22Marry SuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Upreme Qtourt: L/epublit of Tbe BilippineDocument24 paginiUpreme Qtourt: L/epublit of Tbe Bilippinek.satomi.randomacctsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2014 PDFDocument28 pagini2014 PDFJust a researcherÎncă nu există evaluări

- Origin of Revenue Appropriations and Tariff BillsDocument66 paginiOrigin of Revenue Appropriations and Tariff BillsIxhanie Cawal-oÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5 ABAKADA Vs Ermita - 168056 - September 1, 2005 - J. Austria-Martinez - en Banc - DecisionDocument48 pagini5 ABAKADA Vs Ermita - 168056 - September 1, 2005 - J. Austria-Martinez - en Banc - DecisionMary Joy JoniecaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Upreme Q.tourt: 3republif Tbe Bilippine%Document14 paginiUpreme Q.tourt: 3republif Tbe Bilippine%Anthony Isidro Bayawa IVÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heirs of Sy Bang v. SyDocument23 paginiHeirs of Sy Bang v. SyAlexandra Nicole SugayÎncă nu există evaluări

- 191274Document14 pagini191274Zy AquilizanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petitioners Vs Vs Respondents: Third DivisionDocument12 paginiPetitioners Vs Vs Respondents: Third DivisionLex LearnÎncă nu există evaluări

- GR 204887 2021Document12 paginiGR 204887 2021Faithleen Mae LacreteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondents Angara, Abello, Concepcion, Regala & Cruz Mildred A. RamosDocument4 paginiPetitioner vs. vs. Respondents Angara, Abello, Concepcion, Regala & Cruz Mildred A. RamosBryan ManlapigÎncă nu există evaluări

- Susan Basiyo and Andrew William Simmons vs. Atty. Joselito C. AlisuagDocument7 paginiSusan Basiyo and Andrew William Simmons vs. Atty. Joselito C. AlisuagBonito BulanÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. 183905Document11 paginiG.R. No. 183905mar corÎncă nu există evaluări

- HBJNKMLDocument11 paginiHBJNKMLYrra LimchocÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. Nos.195011-19Document11 paginiG.R. Nos.195011-19Abby EvangelistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maricalum Mining Corp. vs. FlorentinoDocument19 paginiMaricalum Mining Corp. vs. FlorentinolouryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sps Flores vs. Sps Estrellado GR 251669 PDFDocument28 paginiSps Flores vs. Sps Estrellado GR 251669 PDFJantzenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Samar-Med Distribution v. NLRCDocument12 paginiSamar-Med Distribution v. NLRCTon RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adalim Vs TalinasDocument9 paginiAdalim Vs Talinasmelchor1925Încă nu există evaluări

- Medyo Important Details: Facts Petitioners' Contentions Respondents' Contentions Issue Held Cases CitedDocument36 paginiMedyo Important Details: Facts Petitioners' Contentions Respondents' Contentions Issue Held Cases CitedJan Aguilar EstefaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tahira S. Ismael and Aida U. Ajijon, G.R. No. 234435-36, February 06, 2023Document22 paginiTahira S. Ismael and Aida U. Ajijon, G.R. No. 234435-36, February 06, 2023Anonymous oGfAqF1Încă nu există evaluări

- Sabio CaseDocument54 paginiSabio Casegod-winÎncă nu există evaluări

- G, Upreme Court: 11.lepublit ofDocument18 paginiG, Upreme Court: 11.lepublit ofBeboy Paylangco EvardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- PCGG Chairman Vs JacobiDocument34 paginiPCGG Chairman Vs JacobiPinky de GuiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SPL 045 Ison vs. PeopleDocument7 paginiSPL 045 Ison vs. PeopleJazztine ArtizuelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- L/Epublic of Tbe Ijuprtmt (Ourt: TbilippineDocument7 paginiL/Epublic of Tbe Ijuprtmt (Ourt: TbilippineDeric MacalinaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 019&038-ABAKADA Guro Party List, Etc. v. Ermita, Sept. 1, 2005Document125 pagini019&038-ABAKADA Guro Party List, Etc. v. Ermita, Sept. 1, 2005Jopan SJÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manila: 3&epublic of Tbe Llbilippine% $upteme !courtDocument22 paginiManila: 3&epublic of Tbe Llbilippine% $upteme !courtLady Lyn DinerosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emmanuel Concepcion, Et AlDocument16 paginiEmmanuel Concepcion, Et AlCari Mangalindan MacaalayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crisostomo vs. SEC (1989)Document11 paginiCrisostomo vs. SEC (1989)JM SisonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heirs of Jose Bang Et Al Vs Rolando Sy, Rosalino Sy, Et Al GR No 114217Document34 paginiHeirs of Jose Bang Et Al Vs Rolando Sy, Rosalino Sy, Et Al GR No 114217rosalinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ll/.epublit of Tbe Llbilippines $upreme Qrourt:fflanila: ChairpersonDocument14 paginiLl/.epublit of Tbe Llbilippines $upreme Qrourt:fflanila: ChairpersonRainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Albenson Enterprises Corp vs. CADocument9 paginiAlbenson Enterprises Corp vs. CAsamantha.makayan.abÎncă nu există evaluări

- Albenson V CA 217 Scra 16Document7 paginiAlbenson V CA 217 Scra 16attyreygarinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anchor Savings Bank VS FurigayDocument16 paginiAnchor Savings Bank VS FurigayBilly NudasÎncă nu există evaluări

- AFRICA - Day 5 Digest TortsDocument23 paginiAFRICA - Day 5 Digest TortsRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Charlie Chan PastaDocument1 paginăCharlie Chan PastaRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Doctrines (Civpro)Document28 paginiCase Doctrines (Civpro)Roberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- TAN CHAY Digest and OriginalDocument5 paginiTAN CHAY Digest and OriginalRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hacienda Luisita Case BriefingDocument5 paginiHacienda Luisita Case BriefingRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- People v. Delos SantosDocument6 paginiPeople v. Delos SantosRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2013 All Inclusive (8.1 - 12M) - CandidateAgreementDocument9 pagini2013 All Inclusive (8.1 - 12M) - CandidateAgreementRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leg Res-Assignment PDFDocument2 paginiLeg Res-Assignment PDFRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1st Assign CIV PRODocument16 pagini1st Assign CIV PRORoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Doctrines (Civpro)Document28 paginiCase Doctrines (Civpro)Roberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- BETTS v. CADocument2 paginiBETTS v. CARoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

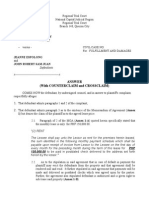

- Jeanne Espolong Answer With Counterclaim and Cross-Claim BDocument4 paginiJeanne Espolong Answer With Counterclaim and Cross-Claim BRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1st Assign CIV PRODocument16 pagini1st Assign CIV PRORoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- SDFSDFDFSDDSFDocument9 paginiSDFSDFDFSDDSFRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Valdez v. Republic (Presumption of Death)Document1 paginăValdez v. Republic (Presumption of Death)Roberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cuenco v. CA (RULE 72, Venue and Process)Document2 paginiCuenco v. CA (RULE 72, Venue and Process)Roberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- TAN CHAY Digest and OriginalDocument5 paginiTAN CHAY Digest and OriginalRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reaction (RTC San Juan)Document2 paginiReaction (RTC San Juan)Roberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spouses Mamaril v. Boy Scout of The PhilippinesDocument15 paginiSpouses Mamaril v. Boy Scout of The PhilippinesRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agency 1919-1932Document9 paginiAgency 1919-1932Roberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Valdez v. Republic (Presumption of Death)Document1 paginăValdez v. Republic (Presumption of Death)Roberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Woodchild - Cuison Digest AgencyDocument25 paginiWoodchild - Cuison Digest AgencyRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crawford ArticleDocument2 paginiCrawford ArticleRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manotok-Serona Digest CaseDocument11 paginiManotok-Serona Digest CaseRoberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Partnership Digest Batch 1Document9 paginiPartnership Digest Batch 1Roberts SamÎncă nu există evaluări

- StudioArabiyaTimes Magazine Spring 2022Document58 paginiStudioArabiyaTimes Magazine Spring 2022Ali IshaanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 35 Affirmations That Will Change Your LifeDocument6 pagini35 Affirmations That Will Change Your LifeAmina Km100% (1)

- Problem Set 2Document2 paginiProblem Set 2nskabra0% (1)

- HYPERLINKDocument2 paginiHYPERLINKmico torreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pangan v. RamosDocument2 paginiPangan v. RamossuizyyyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Verbal Reasoning 8Document64 paginiVerbal Reasoning 8cyoung360% (1)

- ET Banking & FinanceDocument35 paginiET Banking & FinanceSunchit SethiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Front Cover NME Music MagazineDocument5 paginiFront Cover NME Music Magazineasmediae12Încă nu există evaluări

- Physics Project Work Part 2Document9 paginiPhysics Project Work Part 2Find LetÎncă nu există evaluări

- CentipedeDocument2 paginiCentipedeMaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 6-Contracting PartiesDocument49 paginiChapter 6-Contracting PartiesNUR AISYAH NABILA RASHIMYÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine Stock Exchange: Head, Disclosure DepartmentDocument58 paginiPhilippine Stock Exchange: Head, Disclosure DepartmentAnonymous 01pQbZUMMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philips AZ 100 B Service ManualDocument8 paginiPhilips AZ 100 B Service ManualВладислав ПаршутінÎncă nu există evaluări

- EEE Assignment 3Document8 paginiEEE Assignment 3shirleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dayalbagh HeraldDocument7 paginiDayalbagh HeraldRavi Kiran MaddaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- S.No. Deo Ack. No Appl - No Emp Name Empcode: School Assistant Telugu Physical SciencesDocument8 paginiS.No. Deo Ack. No Appl - No Emp Name Empcode: School Assistant Telugu Physical SciencesNarasimha SastryÎncă nu există evaluări

- RA 9072 (National Cave Act)Document4 paginiRA 9072 (National Cave Act)Lorelain ImperialÎncă nu există evaluări

- May Galak Still This Is MyDocument26 paginiMay Galak Still This Is MySamanthafeye Gwyneth ErmitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bible Who Am I AdvancedDocument3 paginiBible Who Am I AdvancedLeticia FerreiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review of The Civil Administration of Mesopotamia (1920)Document156 paginiReview of The Civil Administration of Mesopotamia (1920)George Lerner100% (1)

- United Architects of The Philippines: Uap Membership Registration FormDocument2 paginiUnited Architects of The Philippines: Uap Membership Registration FormDaveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Encyclopedia of Human Geography PDFDocument2 paginiEncyclopedia of Human Geography PDFRosi Seventina100% (1)

- Critical Analysis of The Payment of Wages ActDocument2 paginiCritical Analysis of The Payment of Wages ActVishwesh SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wild Edible Plants As A Food Resource: Traditional KnowledgeDocument20 paginiWild Edible Plants As A Food Resource: Traditional KnowledgeMikeÎncă nu există evaluări