Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Devising The Optimal Preclinical Oncology Curriculum For Undergraduate Medical Students in The United States

Încărcat de

arakbae0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

12 vizualizări9 paginiDevising the Optimal Preclinical Oncology Curriculum for Undergraduate Medical Students in the United States

Titlu original

Devising the Optimal Preclinical Oncology Curriculum for Undergraduate Medical Students in the United States

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDevising the Optimal Preclinical Oncology Curriculum for Undergraduate Medical Students in the United States

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

12 vizualizări9 paginiDevising The Optimal Preclinical Oncology Curriculum For Undergraduate Medical Students in The United States

Încărcat de

arakbaeDevising the Optimal Preclinical Oncology Curriculum for Undergraduate Medical Students in the United States

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 9

Devising the Optimal Preclinical Oncology Curriculum

for Undergraduate Medical Students in the United States

Nicholas J. DeNunzio & Lija Joseph & Roxane Handal &

Ankit Agarwal & Divya Ahuja & Ariel E. Hirsch

Published online: 18 May 2013

#Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013

Abstract A third of women and a near majority of men in

the United States will be diagnosed with cancer in their

lifetimes. To prepare future physicians for this reality, we

have developed a preclinical oncology curriculum that intro-

duces second-year medical students to essential concepts

and practices in oncology to improve their abilities to ap-

propriately care for these patients. We surveyed the oncolo-

gy and education literature and compiled subjects important

to students' education including basic science and clinical

aspects of oncology and addressing patients' psychosocial

needs. Along with the proposed curriculum content, sched-

uling, independent learning exercises, and case studies, we

discuss practical considerations for curriculum implementa-

tion based on experience at our institution. Given the chang-

ing oncology healthcare landscape, all (new) physicians

must competently address their cancer patients' needs, re-

gardless of chosen specialty. A thorough and logically or-

ganized cancer curriculum for preclinical medical students

should help achieve these aims. This new model curriculum,

with accompanying strategies to evaluate its efforts, is es-

sential to update how medical students are educated about

cancer.

Keywords Oncology

.

Curriculum

.

Undergraduate medical

students

.

United States

Introduction

Undergraduate medical education is the cornerstone for

training the next generation of physicians to care for healthy

and ailing members of our society. Medical school curricula

aim to develop students basic and clinical sciences knowl-

edge as well as their professional and clinical skills. Al-

though some fields are systems-based, many others, such as

oncology, are trans-disciplinary and demand mastery of

several topics in parallel.

Cancer patients currently compose a significant subset of

those seeking medical care. In the United States approximate-

ly half of men and a third of women will be diagnosed with

cancer during their lifetimes while about one in five will die of

cancer [1]. Furthermore, as projected by the World Health

Organization, 26 million people worldwide will receive a

cancer diagnosis in the year 2030 alone [2]. Therefore, all

practicing physicians should be able to diagnose cancer and

have at least a basic appreciation for how to address cancer

patients needs, regardless of whether they will serve as the

primary provider or refer the patient to a specialist.

Implementing a cancer curriculum for undergraduate med-

ical students to address these issues was proposed as early as

24 years ago in Europe [3] and addressed more recently by

reviewing published teaching efforts [4]. Cancer education

guidelines for undergraduate medical students over the dura-

tion of their formal education have been developed in Aus-

tralia [5]. However, the Australian recommendations do not

provide council for timely integration of concepts to appro-

priately prepare students for each stage of their schooling.

A detailed outline of basic science and clinical concepts,

as well as social and emotional issues, for training medical

oncologists in the United States [6] is too detailed in many

areas for effectively educating undergraduate medical stu-

dents. In addition, few undergraduate medical curricula

emphasizing oncology in some capacity are available from

the Curriculum Management and Information Tool available

J Canc Educ (2013) 28:228236

DOI 10.1007/s13187-012-0442-0

N. J. DeNunzio

:

R. Handal

:

A. Agarwal

:

D. Ahuja

:

A. E. Hirsch (*)

Department of Radiation Oncology, Boston University School

of Medicine, 830 Harrison Avenue, Moakley Building LL,

Boston, MA 02118, USA

e-mail: Ariel.hirsch@bmc.org

L. Joseph

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Boston

University School of Medicine, 715 E. Concord Street,

Boston, MA 02118, USA

through the Association of American Medical Colleges [7].

Consequently, the development of a curriculum specific to

undergraduate medical students that exposes students to

basic concepts in caring for their cancer patients is essential

prior to their clinical rotations [8, 9].

Some medical schools have begun to integrate aspects of

cancer curricula into their undergraduate medical education

courses with specific learning objectives [10, 11]. At our

institution, we have developed a formal preclinical oncology

curriculum for undergraduate medical students to systemat-

ically address both traditional basic science coursework and

elements essential to providing holistic care to complex

cancer patients. Despite the increasingly blurred lines de-

marcating preclinical and clinical portions of undergraduate

medical education curricula, preclinical here refers to the

first two years during which students traditionally spend the

bulk of their time in a classroom setting.

The revised curriculum proposed here, modeled from that

mentioned above, is an attempt at tailoring concepts and

methods in oncology education to fulfill unmet needs. In an

effort to achieve this end, the curriculum addresses many of

the requirements deemed important by the Licensing Com-

mittee for Medical Education (LCME) for sound develop-

ment of an undergraduate medical curriculum [12] as well as

many of the professional competencies emphasized and

developed by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Med-

ical Education (ACGME; Fig. 1a) for residency programs

[13, 14]. We hope readers find this curriculum and sug-

gested evaluation techniques helpful in their efforts to im-

prove cancer education domestically and globally.

Cancer Education in the United States

Existing cancer curricula at some medical schools in the United

States during preclinical education focus differentially on can-

cer prevention and cancer survivorship. After the American

Association for Cancer Education published recommendations

based on a Cancer Education Survey of 126 medical schools, a

few medical schools made curriculum reforms to increase can-

cer prevention and screening education [10]. Boston University

incorporated an additional nine hours of lectures, case-based

learning, and skills laboratories on cancer prevention and

screening. As a result, self-reported skill level for counseling

tobacco cessation, tobacco prevention, sun protection and early

detection of breast, skin, and cervical cancer increased [15]. The

University of CaliforniaLos Angeles (UCLA) implemented a

similar curriculum reformand survey evaluations showed skills

practice was the greatest contributor to improvement in cancer

prevention and screening competency as perceived by the study

participants [11].

While there have been multiple advances in the area of

cancer prevention and screening, education on survivorship

has been limited. In fact, a literature search identified

only one comprehensive curriculum on the latter topic.

It describes a survey and knowledge-based examination

of 211 senior medical students from UCLA, University

of CaliforniaSan Francisco (UCSF), and Drew Univer-

sity that show that 42 % displayed no or incorrect

knowledge about basic survivorship terminology and

37 % lacked knowledge of essential elements of a

comprehensive cancer history. The majority also felt

unprepared to manage the long-term care of cancer

patients [16]. In response to this dearth in cancer survivorship

education, UCLA, UCSF, and Drew created a four-year inte-

grated cancer survivorship curriculum under the National

Cancer Institute Cancer Education Grants Program (R25).

The curriculum is based on individual units consisting of

lectures, problem-based learning exercises, and standardized

patient exercises throughout medical school [17]. However,

even this expansive and much-needed curricular innovation

focuses on only cancer survivorship education and in a scat-

tered modular style rather than in the style of a dedicated,

much more inclusive oncology block.

Fig. 1 a Pie chart depicting the six ACGME competencies fulfilled by

graduate medical education programs. b Venn diagram representing

our ideal preclinical oncology curriculum (black rectangle) that shows

how each section develops some or all of the ACGME competencies as

shown by inset pie charts

J Canc Educ (2013) 28:228236 229

How to Make It Happen: Curriculum Design

We developed this comprehensive preclinical oncology cur-

riculum from the perspectives of patients, caregivers, physi-

cians and other healthcare professionals. In deciding

whether a given topic is appropriate for inclusion we con-

sidered several factors:

Medical Knowledge

Basic and clinical science principles provide a foundation

for understanding epidemiology, carcinogenesis, and princi-

ples of surgical, radiation, and systemic treatments. Scien-

tific concepts across cancers (e.g., acquired DNA mutations,

viral infections, inherited genetic defects) should be inte-

grated while avoiding esoteric molecules and signaling

pathways. Reinforcing themes and information about spe-

cific tumors across lectures that utilize interactive audience

response systems provides repetition and student participa-

tion to facilitate students pattern recognition and long-term

retention [1821]. Framing the information in the context of

clinical case discussions prepares students to address prob-

lems as practicing physicians. Include topics such as the

pathophysiology, methods for detection, and standard

approaches to treatment. Consider emerging and niche tech-

nologies and clinical algorithms but relegate any in-depth

discussion to the third and fourth years.

Patient Care, Population Studies

Preclinical medical students need to understand the epidemi-

ology of common cancers (gender, genetics, environmental

exposures, socioeconomic status, geographic distribution,

etc.) as well as the utility of prevention, lifestyle modification

(e.g., smoking cessation) and screening. Exercise, in particu-

lar, with its many benefits in healthy and sick individuals alike

[22] provides common approaches to disease prevention and

cure and may alleviate psychosocial stressors that contribute

to comorbidities like anxiety, depression, and sleeplessness.

Given that patient populations may differ significantly,

students should be introduced to common cancers but the

preclinical oncology curriculum must have flexibility to

reflect the training environment, including cancer variants

and the resources at the medical schools principal instruc-

tional sites.

Patient Care, Psychosocial Aspects

To produce well-rounded and optimally prepared physi-

cians, students must consider how the psychosocial ele-

ments of a patients life influence their access to care,

compliance with diagnostic and treatment plans and, ulti-

mately, response to treatment. How a patients psychosocial

stressors should be treated depends on the stressor itself

[23]. Overall, the oncology literature on psychosocial stres-

sors is not terribly robust [24], but does suggest that various

stressors may amplify morbidity and mortality among can-

cer patients. In fact, mindbody interactions profoundly

influence medical outcomes for some non-cancerous pathol-

ogies like irritable bowel syndrome [25].

Students should also be introduced to palliative and end-

of-life care. They must be competent in giving bad news,

pain management and managing terminal illnesses for

patients and their families. Physicians must also be skilled

at anticipating and addressing patients psychosocial needs

given the physical, emotional, financial, and social stressors

patients are likely to encounter. Although palliation has

traditionally been reserved exclusively for the weeks or

months preceding a patients death, attention to symptom

management is worth pursuing concurrently with active

treatment to increase the quality of life, improve survival

and even reduce healthcare expenditures [26, 27]. Providing

palliative care and support to children and their families

requires special expertise and sensitivity [28] and may lie

beyond the scope of a more generalized oncology curriculum.

Integrating Professionalism and Communication to Improve

Patient Care

How physicians communicate with patients as well as how

they interact with colleagues in coordinating patient care are

both important. Medical students must learn to not only

consistently relay information to the patient that is directly

related to their disease, including treatment plan, prognosis,

and future options, but also address their psychosocial

needs, whether for adults [29] or children [30].

Medical students must be trained to deliver bad news

professionally but with a humanistic touch. Per Millers

pyramid for assessing clinical competence, clinical compe-

tence is gained in several steps (Fig. 2) [31]. In the oncology

block, small group discussions and mock patient and phy-

sician communication sessions (Topics 5658, Table 1) lay

the groundwork for the development of these skills, which

then are further developed during students third and fourth

(clinical) years of medical school. Given the complex com-

munication required, a single session is insufficient to de-

velop this skill. Rather, students must have repeated

opportunities for reflection, synthesis, and practice [13, 14,

32] although breaking bad news to patients need not occur

on a topic-specific basis [33]. Therefore, schools have great

flexibility in how and when to impart appropriate knowl-

edge and experiences during the preclinical years.

Physicians must also communicate well with both

patients and their colleagues. Certainly, given the large

number of professionals who care for a single patient, mis-

communication (or a lack of communication) is common

230 J Canc Educ (2013) 28:228236

[34] and not just in the treatment of cancer patients [35]. All

patients and specialties would benefit from attention to

better interprofessional communication.

Based on the aforementioned considerations we developed

six learning objectives to guide curriculum design and topics

(Table 2).

How to Make It Happen: Implementation

and Follow-Up

Interspersed Discussions vs. Modular/Block Format

A given curriculum may be taught in a variety of ways.

Preclinical courses may be organized by scientific discipline,

organ system, or clinical specialty. Oncology can be integrated

into that of other systems modules (e.g., pathology and clin-

ical presentation of pancreatic adenocarcinoma within the

gastrointestinal system) or relegated to an oncology-centric

block or module. We and others [4] believe that the block

format, welcomed by the students who have progressed

through and reflected upon it at our institution (unpublished

data), is more effective to cohesively present integrated mate-

rial that may otherwise be lost if dispersed throughout the

entire preclinical undergraduate medical curriculum. The one

study comparing student perceptions of interspersed discus-

sions integrated throughout the curriculum compared to a

modular format on specific subjects that a literature search

revealed showed that students in the interspersed discussion

style curriculumare significantly less satisfied with the quality

and quantity of their education on a given subject matter

compared to the modular curriculum model [36].

A consolidated cancer curriculum is particularly helpful

in introducing topics that are essential in treating many

cancers but may not warrant significant attention when

discussing any single pathology. Lectures on the principles

of surgical, chemotherapeutic, and radiation treatments are

often lost in an interspersed format. The lack of emphasis on

radiation oncology in the undergraduate medical curriculum

and strategies to address this issue were recently reviewed

[37, 38]. This is worrisome given that nearly 60 % of all

cancer patients receive radiotherapy as part of their treat-

ment regimens [39]. Students understanding of the under-

lying principles and patterns among cancers and their

treatments can be lost in the absence of an oncology block

strategy.

If an interspersed cancer curriculum must be employed, a

director or small team of faculty (to include, e.g., medical,

surgical, and radiation oncologists, psychiatrists, as well as

allied health professionals) should provide oversight.

The interspersed curriculum could also be supplemented

with the consolidated block towards the end of the preclin-

ical years if time permits. As such, the implementation of

both approaches would allow for repetition, which would

enhance retention as well as comprehension.

Sample Schedule

To efficiently incorporate the basic tenets outlined into a

cohesive program of study for undergraduate medical stu-

dents, we provide an outline of an oncology block adapted

from the current version in use at the Boston University

School of Medicine (BUSM; Table 1).

BUSM Preclinical Oncology Block

Since its inception in 2009, our preclinical oncology block

has exposed students to basic science and clinical concepts

in oncology as part of our horizontally integrated Oncology

Education Initiative (OEI) [40]. Scientific lectures are paired

with those relating to clinical aspects of a given disease or

group of diseases. For example, lectures 20, 29, and 35 are

devoted to the pathology of lung, genitourinary, and breast

cancers, respectively, while 21, 30, and 36 discuss the

epidemiology, clinical presentations, effective diagnostic

modalities, therapeutic options, and preferred treatment reg-

imens. Students thus appreciate how intricately biomedical

research and clinical care are intertwined.

A dedicated oncology block provides several opportuni-

ties for curricular integration. Indeed, schools are investi-

gating vertical and horizontal integration of disciplines in

response to blurred lines demarcating traditional disciplines

secondary to an ever-evolving medical knowledge base [41,

42]. At BUSM, gross anatomy, histology, pathology, radi-

ology and oncology are integrated and discussed in a small-

group format in the designated oncology block. Students

rotate through stations of radiology images to develop dif-

ferential diagnoses before viewing gross and microscopic

features of classic neoplasia. Data are also posted online for

students to study independently. Since BUSM uses digital

microscopy to teach histology, each of these sessions is also

Fig. 2 Millers pyramid of clinical competence. The oncology block

proposed here relies on the three base levels while relegating the top

level to clinical studies in the later years of medical school

J Canc Educ (2013) 28:228236 231

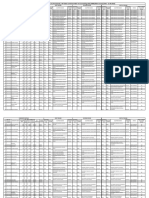

Table 1 List of topics for the preclinical oncology block

Lecture Topic Time (min)

1 Epidemiology of Cancer 50

2 Introduction to the Cell Cycle and Neoplasia 50

3 Cytopathology of Neoplasia 50

4 Principles of Cancer Biology and Tumor Immunology 50

5 Etiologies of Cancer: Molecular, Viral, and Environmental 50

6 Molecular Diagnosis (including Tumor Markers) and Laboratory Techniques 50

7 Imaging Modalities in Oncology 50

8 Self-Study: Principles of Oncology and Cancer Biology

a

9 Case Studies 50

10 Preventative Medicine's Role in Stopping Cancer Before It Starts 100

11 Classifying Cancers: Evaluating Tumor Grade and Stage 50

12 Cancer Treatment Strategies: Surgery, Radiation, Chemotherapy 50

13 Introduction to Chemotherapy 50

14 Introduction to Radiation Oncology 50

15 Self-Study: Foundations of Clinical Oncology

a

16 Case Studies 50

17 Introduction to Cancerous Tissue Types and Nomenclature 50

18 CNS Tumors Pathology 50

19 CNS Tumors Clinical 50

20 Lung Cancer Pathology 50

21 Lung Cancer Clinical 50

22 Pathology Self Study Case: Lung Cancer

a

23 Cases Lung and CNS Cancers 50

24 Esophagus and Gastric Cancer 50

25 Tumors of Pancreas/Polyps and Cancer of the Colorectum 50

26 Colon, Liver and Pancreas Cancer Clinical 50

27 Cases GI Tumors 50

28 Pathology Self Study Case: Colon Cancer

a

29 Renal, Urologic and Prostate Cancer Pathology 50

30 Renal and Urologic and Prostate Cancers Clinical 50

31 Pathology Self Study: Seminoma of Testis

a

32 Pathology Self Study: Prostate Carcinoma

a

33 Ovarian Neoplasia 50

34 Pathology Self Study Case: Cervical Cancer

a

35 Breast Cancer Pathology 50

36 Breast Cancer Clinical 50

37 Pathology Self Study Case: Breast Cancer

a

38 Cases Renal, Urologic, and Reproductive Organ Cancers 50

39 Skin Cancers 50

40 Cases Skin Cancers 50

41 Bone and Soft Tissue Cancer 50

42 Self Study: Bone, Skin, and Soft Tissue Cancers

a

43 Gross Pathology Demo Cases 50

44 Lymphomas 50

45 Leukemias 50

46 Lymphoproliferative Disorders (e.g., myeloma, MGUS, PV) 50

47 Cases 50

48 Pathology Self Study Cases: Leukemia, Lymphoma, Lymphoproliferative Disorders

b

49 HematologyOncology Pathology Slide Review 50

232 J Canc Educ (2013) 28:228236

linked online to normal histology that was learned during

first-year coursework.

Clearly, the successful coordination and implementation

of an effective oncology curriculum requires inputs from

molecular and cellular biologists, pathologists, pharmacolo-

gists, medical, surgical and radiation oncologists, epidemi-

ologists, family practitioners, radiologists, microbiologists,

psychiatrists, and others. While each individual cannot pro-

vide input on each lecture, everyones assistance is needed

to integrate the material into a cohesive course with planned

repetition across lectures to enhance the blocks overall

impact.

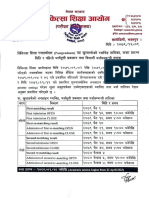

Student evaluations have strongly supported our compre-

hensive integration of the BUSM hematologyoncology

block as reflected by survey data from the Office of Medical

Education (OME) at our institution and survey data from the

radiation oncology department that is administered to third-

and fourth-year medical students (Fig. 3). The OME, among

its other functions, independently audits courses through

soliciting student feedback. Between the first two install-

ments of the oncology block (20102011 and 20112012),

student assessment improved in multiple dimensions. These

include student evaluations of good or excellent regard-

ing how well learning methods fostered learning (from 87 %

in 20102011 to 94 % in 20112012), integration of mate-

rial throughout the module (from 79 % to 87 %), and

organization of topics within the block (from 75 % to

91 %). These improvements may stem from a variety of

changes made to the module since its debut, including

providing guidance on how to approach the material in the

Table 1 (continued)

Lecture Topic Time (min)

50 Transfusion Medicine 50

51 Rare Cancers: Being Prepared for Them 50

52 Pediatric Oncology: Tumor Types and Special Considerations 100

53 Current Topics and Trends in Oncology 100

54 Integrated Summary of Organ Systems and Clinical Science Foundations 50

55 Integrated Summary of Organ Systems and Clinical Science Foundations 2 50

56 Professional Communication: Physician to Physician 50

57 Professional Communication: Physician to Patient 50

58 Providing Psychosocial Support to Patients 50

59 Palliative and End-of-Life Care 50

60 Self-Study: Communication in Oncology

a

61 Cases/Discussion: Communication in Oncology 50

62 Experiential Learning: Interviewing a Cancer Patient and Writing a Report 150

63 Oncology Examination Review 100

Outline of a mature oncology curriculum. Based on the preclinical hematology/oncology block at the Boston University School of Medicine, this

expanded curriculum is comprised of fifty-six 50-min periods coupled with independent study sessions over approximately 16 class days, excluding

review. It is composed of four subsections: Medical Knowledge of Cancer: Basic Science (19), Medical Knowledge of Cancer: Clinical

Foundations (1016), Cancers by Organ System (1755) and Cancer Patient Care (5662)

a

Independent learning by student, so it is expected that the amount of time necessary for each student to complete the task will vary. The average

student should be able to complete each self-study case in 50 min

b

Similar to other self-study cases but more comprehensive so the average target time for students to complete it is doubled, or 100 min

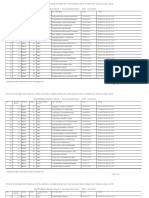

Table 2 Condensed learning objectives for the preclinical oncology block

Objective ID Description

1 Describe epidemiological concepts in relation to common cancers and the importance of prevention and screening

2 Identify the molecular basis of neoplasia in hematology and oncology

3 Recognize the pathophysiology, morphology, and clinical characteristics of common tumors that affect various organ systems

4 Understand cancer diagnosis, including clinical examination, diagnostic tools, and histopathological classification

5 Identify the basic principles of cancer therapy and multidisciplinary management

6 Develop communication skills needed to counsel and support patients and to work professionally with colleagues

Learning objectives for a preclinical oncology block. Content for lectures in the proposed block are centered around these six broad educational

aims. They canvas knowledge of the basic and clinical sciences as well as developing good communication skills

J Canc Educ (2013) 28:228236 233

block during an overview lecture, condensing the lecture

schedule and topics discussed for a more tractable syllabus

to be covered, and a modified end-of-course examination

that strove to test understanding of broad themes rather than

minute details. We are encouraged by these initial improve-

ments and aim to achieve even greater positive feedback

from future classes as further improvements are made to the

oncology block in response to student feedback.

Ideal Preclinical Oncology Curriculum Content

The preclinical oncology curriculum at BUSM addresses

many important issues and concepts and may serve as a

model for other medical schools. Many elements, notably

the high level of interdisciplinary discussions within and

between lectures, are strengths of our existing model. We

have supplemented the existing foundation at BUSM with

topics that are integral in preparing medical students to

competently care for cancer patients (Fig. 1b).

Finally, educational administrators must be flexible in

implementing this curriculum effectively into their already

packed lecture schedules. Some of the topics covered within

individual lectures could also be covered in other courses or

in small group workshops. We use the term lecture to

account for time needed to convey knowledge or develop

a skill set in whatever method is deemed most effective,

without intending to limit the instructional forum to a large

lecture hall. For example, BUSM has a weekly Integrated

Problems (IP) course to develop practical research and com-

munication skills. Focusing heavily on group discussions

and team problem solving, IP does not rely on a student

patient or facultypatient interface to achieve its goals. This

distinction enables IP to accommodate specific types of

material such as topics related to cancer patient care (lec-

tures 5662). Students presented with a case of an elderly

diabetic woman with metastatic breast cancer would re-

search treatment options for both conditions and also learn

how to best communicate with other healthcare professio-

nals and the patient in identifying treatment goals and how

to achieve them. This active learning paradigm can therefore

supplement basic science and clinical knowledge accrued in

other lectures given the emphasis on interpersonal interac-

tions and behaviors.

Additional Considerations

Insertion into the Academic Calendar

Where to insert an oncology block in the general preclinical

curriculum deserves consideration. Students lack of famil-

iarity with topics that play a central role in many cancers

(e.g., virology of EpsteinBarr virus and human papilloma

virus in causing B-cell lymphoma and cervical cancer, re-

spectively) argues against introducing oncology too early.

We begin the second year with a Fundamentals of Medical

Knowledge section that addresses essential material in

pathology, microbiology, and pharmacology to set the stage

for an oncology block later on.

Administering the block at the end of the preclinical

curriculum builds on students familiarity with basic con-

cepts in pathology, microbiology, pharmacology, patho-

physiology, and health law to optimally address such a

multifaceted topic as cancer. However, delayed scheduling

may hinder long-term memory consolidation of such com-

plex material. Providing exposure to many technical terms,

with subsequent testing, prior to the oncology curriculum

can position the oncology curriculum to organize these

concepts.

Finally, providing the block in the middle of the second

year may allow for sufficient mastery of the needed con-

cepts and vocabulary as well as time for integration of basic

medical knowledge prior to caring for oncology patients.

Incorporation of Current Topics

In addition to the typical subjects for consideration we also

scheduled time to introduce the most recent findings, and

technological advancements in cancer research and patient

care (e.g., lecture 53 in Table 1). These current topics may

be discussed in a small-group format as part of problem-

based learning sessions, common in U.S. medical schools

[43], or in a traditional lecture environment, and need not

tax a schools existing classroom time. The key is to engage

students and to stimulate interest in understanding the evo-

lution of tools available to physicians for cancer diagnosis

and treatment.

Fig. 3 Graph displaying results from a student evaluations adminis-

tered in 20092010 with the following statements: a Oncology is

important in medical education. b I am excited to be part of the

multiyear oncology block. c The oncology block was effective at

contributing towards a vertically integrated cancer curriculum. d The

oncology block was effective at contributing towards my medical

education. Black bars indicate strongly agree and agree student

responses while gray bars include neither agree nor disagree, dis-

agree, strongly disagree, and don't know responses

234 J Canc Educ (2013) 28:228236

Assessment and Follow-up of Curriculum

Despite our best efforts to improve medical student oncolo-

gy preclinical education, evaluating successes and progress

over time would be difficult without standard metrics, with-

in and among medical schools. A general exit examination

prior to graduation has been proposed in Australia to ascer-

tain equivalent achievement [44]. For similar reasons, we

recommend that an oncology-specific exam be administered

during the preclinical medical curriculum, ideally through

the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) [45]. An

established preclinical oncology shelf examination may

promote educational scholarship and help determine what

pedagogical methods work best. The NBME could also

provide results for individual and school performance for

oncology-based questions on Step 1 and Step 2, Clinical

Knowledge licensing exams, as it does for organ systems.

We have recently initiated collaboration with ASCO and the

NBME to assess USMLE oncology-related content.

Finally, assessment of students capacities to be empathic

towards patients as well as good communicators among

patients and fellow healthcare providers should not be

neglected. The subjective nature of these topics makes such

determination more difficult but the anticipated benefits

make the additional effort well worth it. One possible way

to test students in these areas is to make use of standardized

patients that many schools already employ to evaluate a

wide range of clinical skills.

Summary and Conclusions

We have described an overview of an oncology curriculum

for second-year medical students to prepare them to care for

oncology patients in their clinical rotations and eventual

practice. Students need sufficient basic oncology concepts,

knowledge and clinical skills to facilitate the diagnosis of

cancer and appropriate referral. Conversely, medical schools

need to avoid the temptation to include subject matter more

appropriate for residents and fellows.

Important elements of a preclinical oncology curriculum

are discussed as well as suggestions for implementation and

a proposed strategy for evaluating these efforts. An effective

preclinical oncology curriculum relies on active technology-

based lectures and team-based communication exercises to

teach medical students the essentials of cancer terminology

before entering the clinical portion of their curriculum. We

will continue to systematically establish core competencies

in cancer patient management for the medical student. As

part of a national community of physicians and educators,

we share this model curriculum and welcome feedback so it

can be improved. Through collaboration, we hope to devel-

op a consensus around content requisite for modern cancer

education of undergraduate medical students while allowing

flexibility for each school to adapt the curriculum to its

institutional learning objectives to best serve its patients.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval has been granted by the Institutional Re-

view Board at the Boston University School of Medicine to

collect participant survey information from medical students

as part of the Oncology Education Initiative.

Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank Dean Karen

Antman for thoughtful and critical review of this manuscript. This

work is supported, in part, by a Varian Medical Systems/Radiological

Society of North America Education Seed Grant.

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of

interest.

References

1. American Cancer Society (2012) Cancer facts and figures 2012.

American Cancer Society, Atlanta

2. International Agency for Research on Cancer (2009) World cancer

report 2008. World Health Organization, Geneva

3. Peckham M (1989) A curriculum in oncology for medical students

in Europe. Acta Oncol 28(1):141147

4. Gaffan J, Dacre J, Jones A (2006) Educating undergraduate med-

ical students about oncology: a literature review. J Clin Oncol

24(12):19321939

5. Oncology Education Committee (2007) Ideal oncology curriculum

for medical schools. The Cancer Council Australia

6. Muss HB, Von Roenn J, Damon LE, Deangelis LM, Flaherty LE,

Harari PM, Kelly K, Kosty MP, Loscalzo MJ, Mennel R, Mitchell

BS, Mortimer JE, Muggia F, Perez EA, Pisters PW, Saltz L,

Schapira L, Sparano J (2005) ACCO: ASCO core curriculum

outline. J Clin Oncol 23(9):20492077

7. Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Curriculum

Management Information Tool (CurrMIT) (2011) www.aamc.org/

currmit. Accessed November 29, 2011

8. Barton MB, Bell P, Sabesan S, Koczwara B (2006) What should

doctors know about cancer? Undergraduate medical education

from a societal perspective. Lancet Oncol 7(7):596601

9. DeNunzio NJ, Hirsch AE (2011) The need for a standard, system-

atic oncology curriculum for U.S. medical schools. Acad Med

86(8):921

10. Dajani Z, Geller AC (2008) Cancer prevention education in United

States medical schools: how far have we come? J Cancer Educ

23(4):204208

11. Wilkerson L, Lee M, Hodgson CS (2002) Evaluating curricular

effects on medical students' knowledge and self-perceived skills in

cancer prevention. Acad Med 77(10 Suppl):S5153

12. Licensing Committee on Medical Education (2010) Functions and

structure of a medical school: standards for accreditation of med-

ical education programs leading to the M.D. degree

13. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (2008)

Change and improvement in the learning environment. ACGME

Bulletin, Chicago

14. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (2008)

Envisioning the future of "competencies". ACGME Bulletin, Chicago

J Canc Educ (2013) 28:228236 235

15. Geller AC, Prout MN, Miller DR, Siegel B, Sun T, Ockene J, Koh

HK (2002) Evaluation of a cancer prevention and detection curric-

ulum for medical students. Prev Med 35(1):7886

16. Uijtdehaage S, Hauer KE, Stuber M, Go VL, Rajagopalan S,

Wilkerson L (2009) Preparedness for caring of cancer survivors:

a multi-institutional study of medical students and oncology fel-

lows. J Cancer Educ 24(1):2832

17. Uijtdehaage S, Hauer KE, Stuber M, Rajagopalan S, Go VL,

Wilkerson L (2009) A framework for developing, implementing,

and evaluating a cancer survivorship curriculum for medical stu-

dents. J Gen Intern Med 24(Suppl 2):S491494

18. Mastoridis S, Kladidis S (2010) Coming soon to a lecture theatre

near you: the 'clicker'. Clin Teach 7(2):97101

19. Rubio EI, Bassignani MJ, White MA, Brant WE (2008) Effect of

an audience response system on resident learning and retention of

lecture material. AJR Am J Roentgenol 190(6):W319322

20. Pradhan A, Sparano D, Ananth CV (2005) The influence of an

audience response system on knowledge retention: an application

to resident education. Am J Obstet Gynecol 193(5):18271830

21. Elashvili A, Denehy GE, Dawson DV, Cunningham MA (2008)

Evaluation of an audience response system in a preclinical opera-

tive dentistry course. J Dent Educ 72(11):12961303

22. Newton RU, Galvao DA (2008) Exercise in prevention and man-

agement of cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 9(23):135146

23. Carlson LE, Bultz BD (2008) Mindbody interventions in oncol-

ogy. Curr Treat Options Oncol 9(23):127134

24. Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, Steptoe A (2008) Do stress-related

psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival?

Nat Clin Pract Oncol 5(8):466475

25. Mayer EA (2008) Clinical practice. Irritable bowel syndrome. N

Engl J Med 358(16):16921699

26. Kelley AS, Meier DE (2010) Palliative carea shifting paradigm.

N Engl J Med 363(8):781782

27. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S,

Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF,

Billings JA, Lynch TJ (2010) Early palliative care for patients with

metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. NEngl J Med 363(8):733742

28. Himelstein BP, Hilden JM, Boldt AM, Weissman D (2004)

Pediatric palliative care. N Engl J Med 350(17):17521762

29. Hack TF, Degner LF, Parker PA (2005) The communication goals

and needs of cancer patients: a review. Psychooncology

14(10):831845, discussion 846837

30. Scott JT, Harmsen M, Prictor MJ, Sowden AJ, Watt I (2008)

Interventions for improving communication with children and

adolescents about their cancer (Review). The Cochrane Library,

The Cochrane Collaboration

31. van der Vleuten CP, Schuwirth LW, Scheele F, Driessen EW,

Hodges B (2010) The assessment of professional competence:

building blocks for theory development. Best Pract Res Clin

Obstet Gynaecol 24(6):703719

32. Rosenbaum ME, Ferguson KJ, Lobas JG (2004) Teaching medical

students and residents skills for delivering bad news: a review of

strategies. Acad Med 79(2):107117

33. Colletti L, Gruppen L, Barclay M, Stern D (2001) Teaching stu-

dents to break bad news. Am J Surg 182(1):2023

34. Fleissig A, Jenkins V, Catt S, Fallowfield L (2006) Multidisciplinary

teams in cancer care: are they effective in the UK? Lancet Oncol

7(11):935943

35. Stillman MD(2008) Physicians behaving badly. JAMA300(1):2122

36. Walsh CO, Ziniel SI, Delichatsios HK, Ludwig DS (2011)

Nutrition attitudes and knowledge in medical students after com-

pletion of an integrated nutrition curriculum compared to a dedi-

cated nutrition curriculum: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Med

Educ 11:58

37. Dennis KE, Duncan G (2010) Radiation oncology in undergradu-

ate medical education: a literature review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys 76(3):649655

38. DeNunzio N, Parekh A, Hirsch AE (2010) Mentoring medical

students in radiation oncology. J Am Coll Radiol 7(9):722728

39. Perez C, Brady L (eds) (2007) Principles and practice of radiation

oncology, 5th edn. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia

40. Hirsch AE, Singh D, Ozonoff A, Slanetz PJ (2007) Educating

medical students about radiation oncology: initial results of the

oncology education initiative. J Am Coll Radiol 4(10):711715

41. Muller JH, Jain S, Loeser H, Irby DM (2008) Lessons learned

about integrating a medical school curriculum: perceptions of

students, faculty and curriculum leaders. Med Educ 42(8):778785

42. Vidic B, Weitlauf HM (2002) Horizontal and vertical integration of

academic disciplines in the medical school curriculum. Clin Anat

15(3):233235

43. Hoffman K, Hosokawa M, Blake R Jr, Headrick L, Johnson G

(2006) Problem-based learning outcomes: ten years of experience

at the University of Missouri-Columbia School of Medicine. Acad

Med 81(7):617625

44. Koczwara B, Tattersall MH, Barton MB, Coventry BJ, Dewar JM,

Millar JL, Olver IN, Schwarz MA, Starmer DL, Turner DR,

Stockler MR (2005) Achieving equal standards in medical student

education: is a national exit examination the answer? Med J Aust

182(5):228230

45. National Board of Medical Examiners (2010) Students Subject

Examinations. http://www.nbme.org/students/SubExam/subex

ams.html. Accessed January 3, 2011

236 J Canc Educ (2013) 28:228236

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Uttar Pradesh Dental CouncilDocument1 paginăUttar Pradesh Dental CouncilFaizan KassarÎncă nu există evaluări

- World Journal of Surgical Oncology: Abnormal HCG Levels in A Patient With Treated Stage I Seminoma: A Diagnostic DilemmaDocument3 paginiWorld Journal of Surgical Oncology: Abnormal HCG Levels in A Patient With Treated Stage I Seminoma: A Diagnostic DilemmaarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide NanoparticlesDocument21 paginiSuperparamagnetic Iron Oxide NanoparticlesarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1471 2490 6 5Document4 pagini1471 2490 6 5arakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 842Document8 pagini842arakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planning of Electroporation-Based Treatments UsingDocument10 paginiPlanning of Electroporation-Based Treatments UsingarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Targeting The Dynamic HSP90 Complex in CancerDocument13 paginiTargeting The Dynamic HSP90 Complex in CancerarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 90 6601867aDocument7 pagini90 6601867aarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of Radiotherapy in Cancer TreatmentDocument9 paginiThe Role of Radiotherapy in Cancer TreatmentarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mosaic JDocument7 paginiMosaic JarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Van DykDocument31 paginiVan DykarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tugas Mata Kuliah Pengolahan CitraDocument5 paginiTugas Mata Kuliah Pengolahan CitraarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The European Society of Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology–European Institute of Radiotherapy (ESTRO–EIR) Report on 3D CT-based in-room Image Guidance Systems- A Practical and Technical Review and GuideDocument16 paginiThe European Society of Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology–European Institute of Radiotherapy (ESTRO–EIR) Report on 3D CT-based in-room Image Guidance Systems- A Practical and Technical Review and GuidearakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Macro Reference GuideDocument45 paginiMacro Reference GuideMarcos Vinicios Borges GaldinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Macros Roimanager3dDocument2 paginiMacros Roimanager3darakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Auto-Align Manuscript Supplement FinalDocument9 paginiAuto-Align Manuscript Supplement FinalarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ki67 Expression and Docetaxel Efficacy in Patients With Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast CancerDocument7 paginiKi67 Expression and Docetaxel Efficacy in Patients With Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast CancerarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Detection of Patient Setup Errors With A Portal Image - DRR Registration Software ApplicationDocument14 paginiDetection of Patient Setup Errors With A Portal Image - DRR Registration Software ApplicationarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy With or Without Chemotherapy For Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma - Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Phase II Trial 0225Document7 paginiIntensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy With or Without Chemotherapy For Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma - Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Phase II Trial 0225arakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Importance of Protocol Target Definition On The Ability To Spare Normal Tissue - An IMRT and 3D-CRT Planning Comparison For Intraorbital TumorsDocument9 paginiImportance of Protocol Target Definition On The Ability To Spare Normal Tissue - An IMRT and 3D-CRT Planning Comparison For Intraorbital TumorsarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Automatic Localization and Delineation of Collimation Fields in Digital and Film-Based RadiographsDocument9 paginiAutomatic Localization and Delineation of Collimation Fields in Digital and Film-Based RadiographsarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Control, Correction, and Modeling of Setup Errors and Organ MotionDocument12 paginiControl, Correction, and Modeling of Setup Errors and Organ MotionarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Equinox BTMB 8003 1 v092009Document4 paginiEquinox BTMB 8003 1 v092009arakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Edge Detection of The Radiation Field in Double Exposure Portal Images Using A Curve Propagation AlgorithmDocument14 paginiEdge Detection of The Radiation Field in Double Exposure Portal Images Using A Curve Propagation AlgorithmarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extremely Low-Frequency Magnetic Field Enhances The Therapeutic Efficacy of Low-Dose Cisplatin in The Treatment of Ehrlich CarcinomaDocument8 paginiExtremely Low-Frequency Magnetic Field Enhances The Therapeutic Efficacy of Low-Dose Cisplatin in The Treatment of Ehrlich CarcinomaarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Honey and Its Mechanisms of Action On The Development and Progression of CancerDocument26 paginiEffects of Honey and Its Mechanisms of Action On The Development and Progression of CancerNurHidayatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Detection of Patient Setup Errors With A Portal Image - DRR Registration Software ApplicationDocument14 paginiDetection of Patient Setup Errors With A Portal Image - DRR Registration Software ApplicationarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Honey and Cancer - Sustainable Inverse Relationship Particularly For Developing Nations-A ReviewDocument11 paginiHoney and Cancer - Sustainable Inverse Relationship Particularly For Developing Nations-A ReviewarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Protective Effect of Yashtimadhu (Glycyrrhiza Glabra) Against Side Effects of Radiation-Chemotherapy in Head and Neck MalignanciesDocument4 paginiProtective Effect of Yashtimadhu (Glycyrrhiza Glabra) Against Side Effects of Radiation-Chemotherapy in Head and Neck MalignanciesNurHidayatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Does Honey Have The Characteristics of Natural Cancer VaccineDocument8 paginiDoes Honey Have The Characteristics of Natural Cancer VaccinearakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- MiR-210 As A Marker of Chronic Hypoxia, But Not A Therapeutic Target in Prostate CancerDocument6 paginiMiR-210 As A Marker of Chronic Hypoxia, But Not A Therapeutic Target in Prostate CancerarakbaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- DRTP Uuer ManualDocument10 paginiDRTP Uuer ManualNavin ChandarÎncă nu există evaluări

- InstwiseadmDocument209 paginiInstwiseadmSaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- TB Quiz - 2023Document2 paginiTB Quiz - 2023Sahil KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- RA-120500 PHYSICIAN Manila 11-2020Document255 paginiRA-120500 PHYSICIAN Manila 11-2020iya gerzonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medical List Regular 100419Document98 paginiMedical List Regular 100419krishnakumars0% (1)

- Orthopedic Surgery Complete IMG ListDocument153 paginiOrthopedic Surgery Complete IMG ListF AbdullaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Executive Rule For CME - PD - SCFHSDocument14 paginiExecutive Rule For CME - PD - SCFHSsevattapillaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Doctor ListDocument1 paginăDoctor ListDebankita MandalÎncă nu există evaluări

- AMEE Guide No. 25: The Assessment of Learning Outcomes For The Competent and Reflective PhysicianDocument16 paginiAMEE Guide No. 25: The Assessment of Learning Outcomes For The Competent and Reflective PhysicianAnonymous wGAc8DYl3VÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Ao Trauma PR Acetab Pelvic Szeged 08.22Document16 paginiNew Ao Trauma PR Acetab Pelvic Szeged 08.22Dr.upendra goudÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alloutment 1st Round AIQ DeemedDocument281 paginiAlloutment 1st Round AIQ DeemedMd Ali MajorÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2018 SATS Membership List For The WebsiteDocument9 pagini2018 SATS Membership List For The WebsiteRubilin NitishaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Minilip Gynae DataDocument85 paginiMinilip Gynae DataShweta jainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ghotki Updated 2023 24Document11 paginiGhotki Updated 2023 24ahmar7698Încă nu există evaluări

- Radiology Log BookDocument51 paginiRadiology Log BookZulqarnain AbidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uttarakhand Round 2 Revised Allotment Dated 29oct 5pmDocument264 paginiUttarakhand Round 2 Revised Allotment Dated 29oct 5pmPrudhvi MadamanchiÎncă nu există evaluări

- First Allotment List of C.G. State Govt./Pvt. MBBS and BDS Course 2021Document80 paginiFirst Allotment List of C.G. State Govt./Pvt. MBBS and BDS Course 2021arindamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Skills Coordinator Job DescriptionDocument6 paginiClinical Skills Coordinator Job DescriptionYee Han KwongÎncă nu există evaluări

- SB 3: Medical Marijuana BillDocument26 paginiSB 3: Medical Marijuana BillSteven DoyleÎncă nu există evaluări

- MOP UP Round Allotment Result DME UG 2023Document38 paginiMOP UP Round Allotment Result DME UG 2023shriram8920Încă nu există evaluări

- Teaching The Humanities in Medical EducationDocument1 paginăTeaching The Humanities in Medical EducationCardiff University School of Medicine C21 Curriculum ShowcaseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippines - Emilio Aguinaldo CollegeDocument12 paginiPhilippines - Emilio Aguinaldo Collegeimes123Încă nu există evaluări

- Khawaja Ms Sialkot MbbsDocument5 paginiKhawaja Ms Sialkot MbbsRayan ArhamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allotments PG Med r1 Web 16082023Document65 paginiAllotments PG Med r1 Web 16082023Tanveer MansuriÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Eligible Candidates MBBS 2019Document7 paginiList of Eligible Candidates MBBS 2019subhamchampÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mecpg2022 Open I ResultDocument155 paginiMecpg2022 Open I ResultJenish LagejuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anaesthesia Science 10Document1 paginăAnaesthesia Science 10KelompokC IPDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deemed Stray Vacancy Round Seats PG MD - Ms - DiplomaDocument39 paginiDeemed Stray Vacancy Round Seats PG MD - Ms - DiplomaManoj KashyapÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enhancing UK Core Medical Training Through Simulation-Based Education: An Evidence-Based ApproachDocument36 paginiEnhancing UK Core Medical Training Through Simulation-Based Education: An Evidence-Based ApproachAndxp51Încă nu există evaluări