Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Intellectual Property ADR Vs Litigation Resolving Intellectual Property Disputes Outside of Court Using ADR To Take Control of Your Case

Încărcat de

sanjeevchaswalDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Intellectual Property ADR Vs Litigation Resolving Intellectual Property Disputes Outside of Court Using ADR To Take Control of Your Case

Încărcat de

sanjeevchaswalDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Intellectual property cases, like most commercial disputes,

start out in court but usually are resolved before trial. Given

the high cost and protracted nature of IP battles, arbitration

and mediation should be considered seriously as options to

take control of a dispute when it arises. This article focuses

on the key factors to evaluate when deciding whether to

arbitrate or mediate an IP dispute.

Intellectual Property

ADR vs. Litigation

T o p i c s c o v e r e

d

Arbitration

Mediation

hoosing a

!esolution Process

!esolving Intellectual Property "isputes #utside of ourt$

%sing A"! to Take ontrol of &our ase

'y Alan (. )owalchyk

Mr. Kowalchyk is a senior vice president and director at the law firm of Merchant

!ould P.".# Minneapolis# practicing in the area of intellectual property law# with an

emphasis on patent litigation# client counseling and alternative dispute resolution.

$his article has %een adapted from the article of the same name pu%lished in the &Dispute

Resolution 'ournal# May('uly )**+,. $he views e-pressed herein are solely those of the

author and do not necessarily state the views of the firm of Merchant !ould P.".# or

any lawyer or client of the firm.

The vast ma*ority of intellectual property litigation, especially cases involving copyright, patent

and trademark infringement claims

+

takes place in the federal courts. ,ike most cases that

set out upon the litigation path, intellectual property cases are most often settled before trial-

the number of cases actually tried in court is small. In .//., for e0ample, slightly more than

1,2// intellectual property disputes were disposed of by federal district courts.

.

,ess than

two percent of these cases went through a trial to verdict.

3

!egardless of when intellectual property lawsuits are settled, the cost of litigating is e0tremely

high. A recent survey published by the American Intellectual Property ,aw Association

reported that a party incurs about 4..5 million in legal fees and costs in an average patent6

infringement case, which usually involves claims for damages between 4+64.7 million.

2

More

than half

of this sum8about 4+.29 million8is incurred up to the completion of discovery. Trademark,

copyright and trade secret cases tend to cost somewhat less than patent cases because they are

less technical. 'ut even these cases can run into the high si0 figures or more when potential

damages are large :i.e., e0ceeding 4+ million;, there are comple0 legal issues and<or a

lengthy trial is anticipated.

7

=ot only is litigation e0pensive, it is a liability on the

balance sheet for as long as the lawsuit e0ists, which can

be a decade or more in patent cases that are appealed and

then retried.

5

A more practical problem is that litigation

continually drains a company>s cash flow. And litigation

is so very public.

?o, when your client is faced with enforcing8or

ac@uiescing to8an intellectual property right, the @uestion

A?hould you advise the company to step into the ringBC

should be asked because there are alternative, less public

and less costly ways of resolving many intellectual

property disputes. The most common are arbitration and

mediation, which are distinctly different alternative

dispute resolution :A"!; processes.

Arbitration

Arbitration is an ad*udicative process that, like a trial, has

a third party decide the dispute. Thus, arbitration is a form

of private *udging. 'ecause arbitration is a creature of

contract, it has a ma*or advantage over litigation$ the

parties can select a decision maker with e0pertise in the

type of intellectual property dispute involved. Arbitration

also has other advantages over litigation. It is potentially

less costly and faster because$

D it is less formal than litigation,

D it allows for less discovery,

D *udicial rules of evidence typically do not apply,

D the arbitrator>s award is final, binding and

enforceable in court, and

D there are limited appeal rights.

The parties bear the costs of arbitration and the arbitrator>s

to this agreement.C Eaving this clause can lower the

temperature of the parties> potentially heated reactions,

which can distract them from ob*ective decision making

after a dispute arises.

If there is no A"! clause in the relevant documents, the

parties can agree to arbitrate post dispute. Eowever, by

that time the parties usually are so at odds with each other

that they are less likely to agree on anything.

The cost of not having a pre6dispute clause is that if

litigation is commenced, the court might re@uire the case

to be arbitrated or mediated before a court6appointed

neutral under a court6referred A"! program. This

obviously takes the decision making about the process

of resolving their intellectual property dispute out of

the parties> hands.

Private commercial arbitration allows the parties to have

that control. ?ignificantly, it allows them to decide on the

rules and procedures that will apply to their arbitration.

In most cases, parties agree to have their arbitration

proceedings administered by an established, neutral

arbitration provider, such as the American Arbitration

Association :AAA;, which has well6tested arbitration

rules8including specialiFed rules for patent disputes8

and acts as an intermediary with respect to neutral

compensation issues.

Arbitration rules tend to be fle0ible and give great

discretion to the arbitrator to manage the proceedings.

Gven when agreeing to arbitration under AAA rules,

parties can ad*ust the rules to meet their needs.

1

'ecause

the arbitration agreement governs the arbitral process,

parties need to pay considerable attention to the terms

of that agreement to increase the likelihood that the

fees. The latter are generally billed at an hourly rate and

can be @uite high. Eowever, because arbitration is usually

a shorter process than litigation, overall costs are usually

lower. In addition, limits on the scope of discovery and

the right to appeal curtail the costs of arbitration.

commencing Arbitration

Eow do parties enter into arbitrationB It is prudent to use

a pre6dispute A"! clause providing for arbitration in the

transaction documents, such as a patent royalty license.

The A"! clause usually states that the parties agree to

arbitrate Aany and all disputes arising out of or related

dispute will be resolved without the need for litigation.

H

issues in Arbitration that

encourage speed and

Flexibility

At the onset of the arbitration, the arbitrator schedules a

pre6hearing conference with the parties at which the

arbitration schedule, discovery and other procedural

matters are discussed and decided. The fle0ibility of

arbitration allows for alternatives. Ior e0ample, at the

hearing that is held on the merits of the case, the matter

of how evidence will be introduced invariably arises.

An arbitrator who is cogniFant of the duty under AAA

pa g e . !esolving Intellectual Property "isputes #utside of ourt$ %sing A"! to Take ontrol of &our ase

rules to conduct a fair hearing while e0pediting the

resolution of the case

9

might urge the parties to

consider having their e0perts testify together and use

witness statements for less important direct testimony.

In most cases, discovery can be better controlled and

usually is completed much faster in arbitration than in

litigation. 'ecause court rules allow discovery of AallC

relevant evidence, intellectual property lawsuits,

especially patent cases, tend to involve wide6ranging

discovery, including many depositions. Arbitration

rules are usually silent on the matter of depositions.

The parties may provide for depositions in their A"!

clause, or they can agree during the pre6hearing

conference on a modest number of depositions of the

most important witnesses. The arbitrator will promptly

decide any discovery disputes that arise.

Patent cases are particularly technical, so a *ury trial can

take weeks. An arbitration hearing on the merits of a patent

case usually takes less time :even though the hearing is

unlikely to be completed in one day;. In arbitration, parties

are advised to focus on the most relevant evidence and

avoid introducing repetitive or cumulative evidence.

There is more fle0ibility in scheduling the arbitration

hearing than that of getting on the court docket.

Iurthermore, arbitration hearings are not marred by

interruptions of the kind that occur in court when the

*udge is suddenly called upon to hear an unrelated matter.

At the end of the hearing on the merits, the arbitrator will

issue a written award, which may be accompanied by an

opinion or brief e0planation of the rationale for the award.

The parties can ask for a written opinion in their arbitration

agreement or at a pre6hearing conference.

Appeal rights in Arbitration

Arbitration is a binding process in which one party may

AwinC all claims and the other Alose.C Eowever, similar

to a court proceeding, arbitrators may reach different

findings on different claims and counterclaims. ?o while

arbitration is considered to be a Awin6loseC process, the

outcome really depends on the merits of each claim

and counterclaim.

There is no automatic right to appeal an arbitration award.

Parties are limited to the grounds set forth in the Iederal

Arbitration Act, since almost all intellectual property cases

involve interstate commerce.

+/

Parties can sidestep the lack of appeal rights by agreeing

to non6binding arbitration. That is not common because

if one party re*ects the award and the case ultimately

proceeds to court, the large legal fees that both parties

initially hoped to avoid would be incurred.

Mediation

%nlike arbitration, mediation is not an ad*udicative process-

it is facilitative in nature. Mediation involves the parties in

a dialogue concerning the disputed issues. Gstablishing who

is right and who is wrong on the issues is not the focus of

mediation$ The goal is to seek business solutions acceptable

to both sides through negotiation, compromise and creative

problem solving.

The mediator>s role is to facilitate communication between

the parties and help them consider a variety of solutions

to all or part of the issues in dispute. These solutions can

involve alternative or additional business arrangements,

including cross6licensing and *oint development of new,

improved or collateral products. There is no limit on the

amount of creativity that can be used in crafting potential

solutions, *ust the parties> willingness to consider them.

Thus, in mediation, the mediator does not decide

substantive issues. ?o in a patent dispute, one should not

e0pect to have a decision by the mediator on such issues as

whether the defendant infringed the patent, whether

the patent was valid or whether the plaintiff actually

owned the patent. ?imilarly, in a trademark case, the

mediator will not decide the likelihood of confusion

between trademarks or whether the plaintiff was the

first to use the trademark and where. These are difficult

issues with large financial conse@uences, and the parties

may not be able to agree on them. Ior this reason, some

attorneys do not recommend mediation to their clients.

Eowever, it can be useful to mediate if only to determine

what the disputed issues are and perhaps reduce

their number.

commencing Mediation

Intellectual property disputes are mediated if the A"!

clause in the transaction documents re@uires it. An A"!

clause commonly provides that in the event of a dispute,

the parties agree to use mediation first- if they cannot

reach an agreement, then they may proceed to arbitration.

pa g e 3 !esolving Intellectual Property "isputes #utside of ourt$ %sing A"! to Take ontrol of &our ase

If there is no A"! clause in the relevant documents and

litigation has been commenced, mediation still can take

place because the parties can agree to mediate while the

lawsuit is pending. Many courts have court6anne0ed

mediation programs that allow them to direct all or most

cases to mediation conducted by a magistrate *udge or

private individual on the court>s roster of mediators.

?ome courts have intellectual property specialists on

their rosters. Generally speaking, in court6anne0ed

mediation, parties do not have the ability to select their

preferred mediator.

A key advantage of private mediation is that parties can

work with a mediator they have chosen, whom they trust

and respect. This is important because for mediation to

be successful, the parties must be willing to discuss

highly sensitive and often proprietary information with

the mediator.

special expertise and co-Mediators

Parties to intellectual property disputes can decide whether

or not the mediator should have special technical e0pertise.

Team mediators are sometimes utiliFed in disputes over

the use of intellectual property, the advantage being more

e0pertise at the mediation table. Ior e0ample, one mediator

may have e0pertise in the field of the disputed technology

:such as computer chips;, and the other may have useful

e0perience in consensus building or the relevant field of

law, i.e., patents, copyrights or trademarks.

%sing co6mediators is more costly but can eliminate the

need for the parties to retain even more costly e0perts

in a field in which a co6mediator has e0pertise. Ior

e0ample, if a co6mediator has e0pertise in preparing

patent applications and %. ?. Patent #ffice procedures,

the parties might feel confident that the nuances of

their positions on issues related to these areas would

be understood without an e0pert>s assistance.

hoosing a !esolution Process

'oth arbitration and mediation are consensual and private

processes, affording parties a greater degree of control

than in litigation.

In arbitration, parties decide which procedures to use as

well as who the arbitrator is. They also have the ability,

through the use of confidentiality agreements, to limit

public

disclosure of the e0istence of an arbitration and what

occurs during and as a result of the process. These

agreements augment statutory protections. Eowever, one

must bear

in mind that J .92 of the federal patent law dictates that

an arbitration award relating to a patent is not enforceable

until the Patent #ffice is given notice of the award.

++

In mediation, parties control who the mediator is and

certain terms, such as the time limit for completion of

mediation. In comple0 IP cases, it is prudent to consider a

time limit for mediation because one party could unduly

delay

the process and thereby preclude a resolution. More

importantly, the parties control the outcome of mediation

because they decide whether to settle or not.

initial considerations in

selecting Litigation

Alternatives

The knowledgeable use of litigation alternatives cannot

occur unless both parties to the IP dispute understand

their business goals. "o they know why they are fighting

and what each wants to accomplishB Is the goal a public

victory in court or to crush the competitionB Maybe

what they really want is to put the litigation behind them

and get back to business- maybe they want to control their

litigation costs.

Ior e0ample, before choosing a process to resolve a patent

dispute, a plaintiff should consider the potential returns

from litigation, including the available damages and how

much product e0clusivity will be available under the scope

of claim coverage provided by the patent. A defendant

should consider the likelihood that it will have to pay

damages,

the amount of such damages and whether product changes

can be made to minimiFe or eliminate the dispute.

Given the costs, time and uncertainty of IP litigation, many

issues may be better addressed using A"! approaches

such as arbitration or mediation.

The competition in high6value technology areas like

pharmaceuticals and medical devices is so fierce that in

many cases traditional civil litigation is heavily relied on

to achieve business goals. It is not rare for these cases to

involve +/ or more patents, which inevitably entangles the

parties in a long and costly process with uncertain results.

Attorneys should @uestion whether it is necessary for their

clients to take this path in every IP dispute.

pa g e 2 !esolving Intellectual Property "isputes #utside of ourt$ %sing A"! to Take ontrol of &our ase

?ince the Iederal !ules of ivil Procedure re@uire courts

to consider the potential for settlement in each case,

+.

before filing a lawsuit, counsel should raise with the client

whether mediation or arbitration8or both se@uentially8

would be a more productive way to achieve the client>s

commercial goals. lients should also be asked to research

earlier trademark and patent licenses and litigation settle6

ment agreements with the adversary to determine whether

any of them re@uire the use of A"! to resolve future dis6

putes arising out of new or related technology.

?ome IP cases clearly should go the litigation route$ cases

that present novel legal issues, where a legal precedent

is desired for future enforcement efforts and where

court6supervised discovery may be necessary because

of the level of detail needed to obtain critical facts

regarding the development of an invention. Iull discovery

and court involvement may be re@uired in some cases

when dealing with issues like multiple contributions to

an invention, propriety of conduct or the timing of a

competing inventor>s efforts.

'ut many IP cases do not raise novel issues or are not

potentially precedent setting. Thus, it is important to

make a determination in almost every case as to whether

mediation and<or arbitration would be preferable to

litigation. Making this determination depends on a number

of factors. In some cases, one factor may be so dominant

that it determines which form of dispute resolution is best.

In other cases, several factors taken together may weigh

in favor of one process over another. The factors to be

considered are addressed below.

size and importance of the dispute

Many litigators believe that IP disputes involving large

amounts of damages, comple0 legal issues and e0tensive

e0pert testimony are not suited for mediation or

arbitration.

+3

This is too simplistic. There is no reason

to allow the amount of money at stake to rule out

arbitration or mediation.

If the financial resources of the aggrieved party are limited,

litigation is likely to @uickly eat up those resources,

leaving this party without a resolution and without funds.

In these circumstances, mediation is a sensible alternative

and should be considered first.

Many litigators and business e0ecutives believe that when

a company>s survival is at stake, the dispute should be

litigated. Eowever, both arbitration and mediation

allow for confidential treatment of the parties> financial

data, business6planning information and development

work

+2

8protection not available in litigation, at least once

the trial begins. Protective orders typically are effective

only during the discovery phase of litigation, an important

factor to consider when trade secrets or highly competitive

businesses are involved in a dispute. Parties may not want

to discuss their proprietary information in court in front

of competitors who fre@uently monitor IP trials precisely

in order to learn about a competitor>s business. Mediation

and arbitration do not take place in public. Thus, A"!

should not be ignored *ust because an IP case is monetarily

large, comple0 and important.

international disputes

Intellectual property cases that are international in scope

are particularly well suited for arbitration or mediation.

Arbitration is a well6established dispute resolution

mechanism for international commercial disputes, and

mediation is well known in many Asian countries :often

known there as conciliation;. Mediation is also attracting

attention in the Guropean %nion, where there is now a

push to use mediation before another adversarial process.

+7

The reasons for acceptance of A"! in the international

business community include, among others, a lack of

confidence in national courts- unfamiliarity with foreign

laws- concern about long, costly court proceedings-

unpredictable and possibly inconsistent outcomes- and

difficulties with enforcing *udgments obtained in foreign

countries. These considerations are especially applicable

in international IP disputes, since IP rights are issued on a

country6by6country basis. %sing international arbitration

makes it unnecessary to litigate in multiple affected

*urisdictions having unfamiliar procedures, different

legal protections for IP rights and different

enforcement mechanisms.

+5

'y arbitrating a multinational IP dispute in a single dispute

resolution process, the parties can save money and time

and obtain a consistent result.

+1

pa g e 7 !esolving Intellectual Property "isputes #utside of ourt$ %sing A"! to Take ontrol of &our ase

Need for Technical expertise

Another factor bearing on how best to resolve a particular

intellectual property dispute is the technical comple0ity

and need for technical e0pertise.

+H

"istrict court *udges

and *uries tend not to be e0perts in IP and the technologies

involved in patent cases. onsiderable time is needed to

bring them up to speed on such matters as the technical

background :i.e., the state of the art before the patented

invention;- the nomenclature of the technical field- the

teachings in prior patents and publications- and the

advantages of the patent invention.

In arbitration, the parties can select an arbitrator who has

the relevant technical IP e0pertise. It is far easier to

educate this type of arbitrator about the case than a district

court *udge and *ury. An e0perienced patent arbitrator

familiar with Aclaim interpretationC issues will more

@uickly appreciate the important technical terminology and

be

able to more efficiently review and decide the case. In

addition, an e0perienced patent arbitrator tends to have

more time available than a *udge to evaluate the sub*ect

matter of the patent and prior patents, publications and

products :i.e., prior art; that bear on whether the patent

represents a valid, enforceable advance in the technology.

Irom the parties> points of view, knowing that the decision

maker understands the technology and the guiding

principles of intellectual property law can elevate their

confidence in the process because they are ensured that

their positions and technical and scientific arguments

are AheardC and considered. This is important because in

federal court, the *udge, serving as the AgatekeeperC of the

technical and scientific evidence admissible in evidence,

+9

is responsible for determining the relevance and reliability

of proposed e0pert testimony. The *udge may decide to

disallow particular e0pert evidence that one party

considers vital to its case.

Introducing technical and scientific arguments and

evidence is usually easier in arbitration. The arbitrators

typically do not preclude the introduction of an e0pert>s

point of view based on specific reliability criteria. ?o if

e0tensive technical e0pertise is important to the resolution

of a case, arbitration should be seriously considered as

an alternative to litigation.

cost and Time savings

The timesaving in mediation and arbitration usually results

from the greater informality and fle0ibility of these

processes over litigation and the limitations on discovery.

./

importance of the parties relationship

Mediation is noted for preserving business relationships.

Parties with an ongoing business relationship may have

a past intellectual property agreement that provides for

arbitration of disputes. If they don>t, but they want to

continue their relationship, mediation is the best choice

to resolve the dispute.

Parties with an ongoing business relationship know about

each other>s business and can appreciate each other>s

needs and interests, which is why it is beneficial to

consider early mediation over litigation and arbitration.

Although many technology companies operate in a

competitive environment that is not conducive to a Atalk

firstC approach, mediation can facilitate keeping business

goals in focus and reducing the hostility that often

accompanies litigation.

Provided a party protects its litigation options, there is

rarely any downside to mediating a patent or trademark

case, regardless of the parties> past relationship. (hether

a product infringes on a patent claim or on a trademark

for a certain product can be confusing and very fact

specific. ?o the best time to mediate may be after the

most important facts are uncovered through discovery,

since it is at that time that the parties often feel they

have sufficient information to e0plore mutually

beneficial outcomes.

control issues

Arbitration provides the most control over the process.

Parties decide what the arbitrator>s @ualifications should be

and specifically who will serve as the arbitrator. They can

select the rules that will apply, the place of arbitration and

the substantive law that will govern. They work with the

arbitrator to determine the pre6hearing procedures

:including the scope of discovery; and the length of the

hearings. "uring this process, the arbitrator will try to

create efficiencies in order to e0pedite a fair resolution

of the dispute.

pa g e 5 !esolving Intellectual Property "isputes #utside of ourt$ %sing A"! to Take ontrol of &our ase

Mediation provides the parties with the greatest amount of

control over the resolution of their dispute. The parties

control the length of the process, the place of mediation,

the information to be considered and the type of mediator.

The parties can select a mediator who is AfacilitativeC

or Aevaluative.C ommercial parties often prefer an

evaluative mediator with relevant sub*ect matter e0perience

because they want to hear how the mediator thinks a court

or arbitrator would consider issues and<or claims in the

case. The mediator>s views often increase the seriousness

with which settlement proposals and counterproposals are

considered. Iurthermore, in mediation, parties can agree

to business solutions that could not be granted by a court.

!egardless of the type of mediator chosen to facilitate

resolution of the dispute, or the suggestions the mediator

offers for consideration, the parties cannot be forced to

agree to a settlement that they do not want.

onclusion

It is becoming apparent to more and more business

organiFations that the benefits of A"! are substantial

and often outweigh the traditional values of vindication

that have led many to use litigation to handle IP cases.

,itigation makes huge headlines but rarely satisfies

business goals. It depletes cash flow, is a liability on

the balance sheet and offers uncertain results even in

the best situations.

Given the high cost and protracted nature of intellectual

property litigation, early and careful evaluation of how

best to meet business goals involving intellectual property

rights is essential. In many cases, mediation and<or

arbitration can handle IP resolution issues better and more

cost effectively than litigation.

pa g e 1 !esolving Intellectual Property "isputes #utside of ourt$ %sing A"! to Take ontrol of &our ase

e N d N o T e s

+

). /.0.". 11 2332# 233.4a56 see# e.g.# 37 /.0.". 11 )82# ).)().76 27 /.0.". 1 2229 et se:.# 22)74a56 28 /.0.". 1 7*2 et se:.

.

Motivans# ;ederal 'ustice 0tatistics Program# Intellectual Property $heft# )**)6 <ureau of 'ustice 0tatistics 0pecial

Report# =ct. )**9# p. . 4reporting disposal of 8#997 copyright# patent and trademark cases5.

3

Id.# reporting a further %reakdown of intellectual property disputes resolved %y trial verdict in )**) with patent cases 3.)>#

copyright cases 2.7># and trademark cases 2.)>. Id. =f the intellectual property cases terminated %y trial# +2> were disposed of %y

?ury verdict# with ?uries deciding +@> of the patent trials# +9> of copyright trials# and 9+> of trademark trials. Id. =f the )**) cases

terminated

%y trial# plaintiffs were winners 7@> of the time. Id.

2

American Intellectual Property Law Association Report of the Aconomic 0urvey )**7# at I(2*@.

7

Id. at 222()*.

5

0ee# e.g.# !rain Processing "orp. v. American MaiBe Products "o.# 2.7 ;.3d 2392 4;ed. "ir. 2@@@5 4patent infringement case

originally filed in 2@.2 with federal circuit opinion addressing appealed damages issues in 2@@@56 0ee also Rite(Cite "orp. v. Kelley

"o. Inc.#

7+ ;.3d 73. 4;ed. "ir. 2@@75 4patent infringement case initially filed in 2@.3 with damages issues e-tending appeals over 2* years5.

1

AAA Rule 24a5.

H

0ee# e.g.# &Ar%itration "lause "hecklist#, in Alternative Dispute ResolutionDCow to /se it to Eour AdvantageF# 329(

)9 4ALI(A<A "ourse Materials# =cto%er )***5.

9

0ee AAA Rules R(3*4a5 4%5.

+/

@ /.0.". 1 2*.

++

37 /.0.". 1 )@94e5# providing &$he award shall %e unenforcea%le until the notice re:uired %y su%section 4d5 is received %y the

Director., 0ection 4d5 providesG

Hhen an award is made %y an ar%itrator# the patentee# his assignee or licensee shall give notice thereof in writing to the Director. $here

shall %e a separate notice prepared for each patent involved in such proceeding. 0uch notice shall set forth the names and addresses of

the parties# the name of the inventor# and the name of the patent owner# shall designate the num%er of the patent# and shall contain a

copy of the award. If an award is modified %y a court# the party re:uesting such modification shall give notice of such modification to the

Director. $he Director shall# upon receipt of either notice# enter the same in the record of the prosecution of such patent. If the re:uired

notice is not filed with the Director# any party to the proceeding may provide such notice to the Director.

+.

;ed. R. "iv. P. 2+4a5475 4c54@5.

+3

0ee &Alternatives to "ourt Litigation in Intellectual Property DisputesG <inding Ar%itration andIor MediationDPatent and Jon(Patent

Issues#, )) IDAA )82# )83(87 42@.)5.

+2

$om Arnold et al.# &Managing Patent Disputes $hrough Ar%itration#, 9+ Ar%. '. 7(+ 40eptem%er 2@@256 see also Arnold#

&Intellectual Property Disputes, in Alternative Dispute ResolutionG $he LitigatorKs Cand%ook# ch. 29# )32# )93 4Jacy Atlas et al

eds. A<A 0ection of Litigation )***5 4chapter 29 comments on the advantages of ADR for intellectual property disputes5.

+7

httpGIIeu r opa.eu.intIeurle-IenI comIpdfI)**9Icom)**9L*82.en*2. pdf.

+5

&Intellectual Property Disputes#, supra n. 27# at )9).

+1

Id.

+H

0ee Arnold et al.# supra n. 27.

+9

Dau%ert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals# 7*@ /.0. 78@ 42@@35.

./

0ee Arnold et al.# supra n. 27# at 7(+.

pa g e H !esolving Intellectual Property "isputes #utside of ourt$ %sing A"! to Take ontrol of &our ase

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Handbook on the Ecowas Treaty and Financial InstitutionsDe la EverandA Handbook on the Ecowas Treaty and Financial InstitutionsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dr. Shakuntala Misra National Rehabilitation University LucknowDocument16 paginiDr. Shakuntala Misra National Rehabilitation University LucknowAnonymous jNo88FÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter - Iii Mediation: Global Scenario: 3.1 PreludeDocument16 paginiChapter - Iii Mediation: Global Scenario: 3.1 PreludeIshan ThakurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Public Interest Litigation (Pil) PDFDocument15 paginiPublic Interest Litigation (Pil) PDFHimanshu GargÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adr SynopsisDocument2 paginiAdr SynopsisDevashri ChakravortyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final ProjDocument25 paginiFinal ProjStella SebastianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Competition Act, 2002Document25 paginiCompetition Act, 2002Shruti PoddarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uttar Pradesh State Legal Services Authority: Final Draft OnDocument23 paginiUttar Pradesh State Legal Services Authority: Final Draft OnAnkur BhattÎncă nu există evaluări

- WTO D S M I C: Ispute Ettlement Echanism and Recent Ndian AsesDocument4 paginiWTO D S M I C: Ispute Ettlement Echanism and Recent Ndian AsesDharu LilawatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adr Exam June 2021Document3 paginiAdr Exam June 2021CHIMOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prospectus Types, Contents and Legal Remedies For MisrepresentationDocument14 paginiProspectus Types, Contents and Legal Remedies For MisrepresentationsmÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pnacb 895Document183 paginiPnacb 895Umer HayatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kompetenz-Kompetenz (ADR Research Paper)Document14 paginiKompetenz-Kompetenz (ADR Research Paper)Karthik RanganathanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ibc 2016 MDocument11 paginiIbc 2016 MMayank SenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurisdiction On CyberspaceDocument21 paginiJurisdiction On CyberspaceAntarik DawnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alternative Dispute Resolution: Role of Judiciary in Promoting AdrDocument11 paginiAlternative Dispute Resolution: Role of Judiciary in Promoting AdrHarsh Verma100% (1)

- Unit 1 IprDocument37 paginiUnit 1 IprMECH DR.VENKAT PRASATÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report On The Public Policy Exception in The New York Convention - 2015 PDFDocument19 paginiReport On The Public Policy Exception in The New York Convention - 2015 PDFJorge Vázquez ChávezÎncă nu există evaluări

- ADR Mechanisms and Related Legislations in India: DR Ashu DhimanDocument33 paginiADR Mechanisms and Related Legislations in India: DR Ashu DhimanOjasvi AroraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Director's Duty in Misrepresentation of ProspectusDocument34 paginiDirector's Duty in Misrepresentation of ProspectusSanchit JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Industrial Disputes: Any Dispute or Difference Between Employers, Employers and Workmen, or Between Workmen and WorkmenDocument33 paginiIndustrial Disputes: Any Dispute or Difference Between Employers, Employers and Workmen, or Between Workmen and WorkmenMohit SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grounds For Challenge To Arbitral AwardDocument6 paginiGrounds For Challenge To Arbitral AwardNikhil GulianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arbitration and Dispute ResolutionDocument5 paginiArbitration and Dispute ResolutionUtkarsh SrivastavaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ilo Labour LawDocument10 paginiIlo Labour Lawdishu kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emergency Arbitration-Working and EnforceabilityDocument15 paginiEmergency Arbitration-Working and EnforceabilityoptimusautobotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comprimise, Arrangement and Amalgamation NotesDocument6 paginiComprimise, Arrangement and Amalgamation Notesitishaagrawal41Încă nu există evaluări

- (Faculty For Professional Ethics) : Iability FOR Deficiency IN Service AND Other Wrongs Committed BY LawyersDocument22 pagini(Faculty For Professional Ethics) : Iability FOR Deficiency IN Service AND Other Wrongs Committed BY LawyersMukesh TomarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nirma JADR Journal 2019Document20 paginiNirma JADR Journal 2019Shauree GaikwadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Environment Law Porject Sem 4 Sara ParveenDocument20 paginiEnvironment Law Porject Sem 4 Sara ParveenSara ParveenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Synopsis Submitted On: SVKM'S Nmims School of Law, MumbaiDocument4 paginiSynopsis Submitted On: SVKM'S Nmims School of Law, MumbaiArnav DasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class 2 Notes 2.1 NegotiationDocument2 paginiClass 2 Notes 2.1 NegotiationDiana WangamatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987: DR Ashu DhimanDocument44 paginiLegal Services Authorities Act, 1987: DR Ashu DhimanOjasvi AroraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lternative Ispute Esolution Ystems Nternal-: A D R S I IDocument14 paginiLternative Ispute Esolution Ystems Nternal-: A D R S I ISudev SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Role of Arbitration in International ContractsDocument10 paginiRole of Arbitration in International ContractsSPANDAN SARMAÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPC FDDocument18 paginiCPC FDRahul ChaudharyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Irl W Methods of Settling Industrial DisputesDocument28 paginiIrl W Methods of Settling Industrial DisputesManohari RdÎncă nu există evaluări

- IPR - Its Variants & Important Judgements - 13.07.19Document32 paginiIPR - Its Variants & Important Judgements - 13.07.19Akshay ChudasamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trademarks & GIsDocument120 paginiTrademarks & GIssindhuvasudev100% (1)

- FinalDocument24 paginiFinalshiyasethÎncă nu există evaluări

- FD Collective Bargaining in IndiaDocument58 paginiFD Collective Bargaining in IndiaSHUBHAM RAJÎncă nu există evaluări

- AB Competition Law Notes UTSDocument11 paginiAB Competition Law Notes UTSbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bargaining Council For The Building IndustryDocument7 paginiBargaining Council For The Building IndustryAbongileÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Icfai University, Dehradun: Assignment of Labour LawDocument18 paginiThe Icfai University, Dehradun: Assignment of Labour LawAditya PandeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pil 4th Sem Proj PDFDocument11 paginiPil 4th Sem Proj PDFAniket SachanÎncă nu există evaluări

- ADR (Ajith)Document18 paginiADR (Ajith)Ajith ReddyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sciencedirect: Applying Action Design Research (Adr) To Develop Concept Generation and Selection MethodsDocument6 paginiSciencedirect: Applying Action Design Research (Adr) To Develop Concept Generation and Selection MethodsFabiano SanninoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Federalism Icivics LessonDocument2 paginiFederalism Icivics LessonJean-Pierre DelacroixÎncă nu există evaluări

- Piracy of DesignsDocument13 paginiPiracy of DesignsArjun NarainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adr in MalaysiaDocument7 paginiAdr in MalaysiaVui Zen ChanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alternative Dispute Resolution-FinalDocument27 paginiAlternative Dispute Resolution-FinalNiladri SahaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Protection of Trade Secrets-The Key To Surviving The MarketDocument9 paginiProtection of Trade Secrets-The Key To Surviving The MarketShivani KhareediÎncă nu există evaluări

- ADR ProjectDocument14 paginiADR ProjectAartika SainiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Functions of WTODocument3 paginiFunctions of WTORajeev PoudelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historical BackgroundDocument5 paginiHistorical BackgroundAbhinav AroraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Section 9 of Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996Document12 paginiSection 9 of Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996Niti KaushikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trade Remedies Safeguards: Reporters: John Mark Sunga Reo DagumanDocument14 paginiTrade Remedies Safeguards: Reporters: John Mark Sunga Reo DagumanjmsungaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alternate Dispute ResolutionDocument6 paginiAlternate Dispute ResolutionSameer SaurabhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Difference Between MOU and Agreement (Repaired)Document12 paginiDifference Between MOU and Agreement (Repaired)Anugya JhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arbitration, A Form of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), Is A Way To Resolve Disputes OutsideDocument6 paginiArbitration, A Form of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), Is A Way To Resolve Disputes OutsideAnant AgrawalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arbitration LitagationDocument2 paginiArbitration LitagationDavid CodauÎncă nu există evaluări

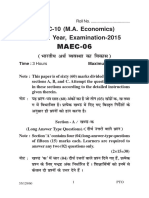

- MAEC-106: MAEC-12 (M.A. Economics) Second Year, Examination-2015Document8 paginiMAEC-106: MAEC-12 (M.A. Economics) Second Year, Examination-2015sanjeevchaswalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maec 06Document8 paginiMaec 06sanjeevchaswalÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Law University, Jodhpur and Institute of Management Technology, Centre For Distance LearningDocument3 paginiNational Law University, Jodhpur and Institute of Management Technology, Centre For Distance LearningsanjeevchaswalÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Paradox of Right To Recall and Reject - A Boon or BaneDocument15 paginiA Paradox of Right To Recall and Reject - A Boon or BanesanjeevchaswalÎncă nu există evaluări

- E-Banking by Sanjeev Kumar ChaswalDocument45 paginiE-Banking by Sanjeev Kumar ChaswalsanjeevchaswalÎncă nu există evaluări

- 26 Marticio Semblante and Dubrick Pilar v. CA, Gallera de Mandaue and Spouses LootDocument1 pagină26 Marticio Semblante and Dubrick Pilar v. CA, Gallera de Mandaue and Spouses LootPaolo Miguel ArqueroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deed of Tenancy Agreement AshuDocument5 paginiDeed of Tenancy Agreement Ashuashutosh2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Max Weber With QuestionsDocument4 paginiMax Weber With QuestionsDennis MubaiwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- People V Quizon DigestDocument12 paginiPeople V Quizon DigestJaypee OrtizÎncă nu există evaluări

- PDS Arman - 2022Document4 paginiPDS Arman - 2022Armando FaundoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Complaint Against MEPCO Zahir PirDocument3 paginiComplaint Against MEPCO Zahir PirarhijaziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wreck Removal ConventionDocument21 paginiWreck Removal ConventionCapt. Amarinder Singh BrarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nistar Patrak and Regulation of FishingDocument39 paginiNistar Patrak and Regulation of FishingPoonam SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4/6 Profile: The Human Design SystemDocument3 pagini4/6 Profile: The Human Design SystemOla Ola100% (2)

- Employee Non-Compete Agreement TemplateDocument4 paginiEmployee Non-Compete Agreement TemplateGina McCune100% (1)

- 09 Juan V JuanDocument10 pagini09 Juan V JuanASL Notes and DigestsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Matthews PED Emails With "Former Clients" and "Former" Law PartnerDocument134 paginiMatthews PED Emails With "Former Clients" and "Former" Law PartnerMichael CorwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- DCAF - BG - 12 - Intelligence Services - 0Document12 paginiDCAF - BG - 12 - Intelligence Services - 0UlisesodisseaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Badelles vs. CabiliDocument11 paginiBadelles vs. CabiliAyra CadigalÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States v. Kevin Tommie Hall, 986 F.2d 1430, 10th Cir. (1993)Document2 paginiUnited States v. Kevin Tommie Hall, 986 F.2d 1430, 10th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Banking OmbudsmanDocument26 paginiBanking OmbudsmanVIVEKÎncă nu există evaluări

- 09-06-2022-1654758244-6-Impact - Ijrhal-1. Ijrhal - Triple Talaq Historical Perspective and Recent TrendDocument10 pagini09-06-2022-1654758244-6-Impact - Ijrhal-1. Ijrhal - Triple Talaq Historical Perspective and Recent TrendImpact JournalsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internship ReportDocument4 paginiInternship ReportSonu SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- EPG Construction Vs CA (Digest)Document2 paginiEPG Construction Vs CA (Digest)カルリー カヒミÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Memorial For A Basic Criminal Law Moot ProblemDocument17 paginiSample Memorial For A Basic Criminal Law Moot Problemarunimabishnoi42% (12)

- Template ABRG - Management Agency Agreement - FormDocument8 paginiTemplate ABRG - Management Agency Agreement - Formrayzaoliveira.ausÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legal Writing Abad ReviewerDocument7 paginiLegal Writing Abad ReviewertrishaÎncă nu există evaluări

- JEMAA1Document4 paginiJEMAA1Ralf JOsef LogroñoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Public International Law: San Beda College of Law - 2003 Centralized Bar Operations Red Notes - Political LawDocument13 paginiPublic International Law: San Beda College of Law - 2003 Centralized Bar Operations Red Notes - Political Lawracel joyce gemotoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cano V CanoDocument11 paginiCano V CanoHenry G Funda II100% (1)

- From H - Md. Shohidul IslamDocument2 paginiFrom H - Md. Shohidul IslamHasan Ibrahim MiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quisumbing vs. GumbanDocument2 paginiQuisumbing vs. GumbanXyra Krezel Gajete100% (1)

- Black Book VishalDocument72 paginiBlack Book VishalVishal Lakhani67% (6)

- Special People V CandaDocument5 paginiSpecial People V CandaTom SumawayÎncă nu există evaluări

- JA - LCR AparriDocument5 paginiJA - LCR AparriJenely Joy Areola-TelanÎncă nu există evaluări