Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

El Pichao 1990

Încărcat de

Maria Marta Sampietro0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

160 vizualizări154 paginiDrepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

160 vizualizări154 paginiEl Pichao 1990

Încărcat de

Maria Marta SampietroDrepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 154

1.

The second field campaign of the project

Per Cornell, Department of archaeology, University of Gothenburg

Susana Sjdin, Department of archaeology, University of Gothenburg

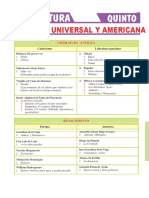

1.1 Introduction........................................................................................................................ 1

1.2 Why centre?........................................................................................................................ 1

Per Cornell, Department of archaeology, University of Gothenburg

References ................................................................................................................................ 4

2. Orgenes de la ocupacin del espacio en el sitio STucTav 5

(El Pichao)

Marta R A Tartusi, instituto de arqueloga, Universidad Nacional de Tucumn

Victor A Nez Regueiro, instituto de arqueloga, Universidad Nacional de Tucumn

2.1 Introduccin ....................................................................................................................... 5

2.2 La periodizacin del noroeste argentino.............................................................................. 5

2.3 Problemas para la identificacin de sitios Formativos y de Integracin regional .................. 6

2.4 Ocupacin del espacio en El Pichao.................................................................................... 8

2.4.1 El perodo Formativo en El Pichao ..................................................................... 8

2.4.2 El perodo de Integracin regional en El Pichao ................................................. 9

2.5 El significado de la ocupacin del espacio para el anlisis de la problemtica

Aguada..................................................................................................................................... 9

Obras citadas .......................................................................................................................... 11

3. Unit 1 as a household and the 1990 excavations in structure

3

Per Cornell, Department of archaeology, University of Gothenburg

3.1 Unit 1 ............................................................................................................................... 13

3.2 What is a household?........................................................................................................ 13

3.2.1 The household as a general concept .................................................................. 13

3.2.2 Household variation.......................................................................................... 15

3.2.3 The spatial frame of the household ................................................................... 16

3.2.4 Remains of home work.................................................................................. 17

3.3 Primeval use, changing patterns of use and abandonment ................................................. 18

3.3.1 Deposits of labour processes through time ........................................................ 18

3.3.2 Unit 1............................................................................................................... 19

3.4 Some concluding remarks................................................................................................. 24

References .............................................................................................................................. 24

4. Sector VIII

Susana Sjdin, Department of archaeology, University of Gothenburg

4.1 Description of a part of sector VIII.................................................................................... 27

4.1.1 The terraces 1 - 8.............................................................................................. 28

4.1.2 The slope above the terrace levels and the smaller terraces ............................... 30

4.1.3 The terrace complex as a whole ........................................................................ 30

4.2 Mapping the constructions and terraces of part of sector VIII............................................ 30

5. Excavacin de la unidad 6 del sectr I del sitio STucTav 5

(El Pichao)

Marta R A Tartusi, instituto de arqueloga, Universidad Nacional de Tucumn

Victor A Nez Regueiro, instituto de arqueloga, Universidad Nacional de Tucumn

5.1 Introduccin ..................................................................................................................... 33

5.2 Descripcin general del sector I ........................................................................................ 34

5.3 Unidad 6........................................................................................................................... 35

5.3.1 Excavacin....................................................................................................... 35

5.3.2 Descripcin de la estructura.............................................................................. 35

5.3.3 Descripcin del entierro.................................................................................... 36

5.3.4 Petroglifos ........................................................................................................ 37

5.3.5 Anlisis del material cermico.......................................................................... 37

5.5 Interpretacin de los hallazgos.......................................................................................... 38

5.5 Las estructuras ceremoniales en el noroeste argentino....................................................... 39

Obras citadas .......................................................................................................................... 41

6. The excavation of the gravematerial

Nils Johansson, Department of archaeology, University of Gothenburg

6.1 Trenches 5-10................................................................................................................... 43

6.2 Trenches 11-15................................................................................................................. 46

6.3 Specific studies of artefact categories within the tombs ..................................................... 49

6.3.1 Ceramics .......................................................................................................... 49

6.3.2 Bone material ................................................................................................... 50

6.3.3 Textiles ............................................................................................................ 51

6.3.4 Metal................................................................................................................ 51

6.3.5 Macrofossil....................................................................................................... 51

6.4 Discussion ........................................................................................................................ 52

6.4.1 Location ........................................................................................................... 52

6.4.2 Dating.............................................................................................................. 52

6.4.3 Construction..................................................................................................... 52

6.4.4 Collective tombs ............................................................................................... 53

6.4.5 Earlier grave field............................................................................................. 53

6.4.6 Not chronologically closed units ....................................................................... 53

6.4.7 A rich artefact material..................................................................................... 54

6.4.8 Specially produced pottery for a grave context .................................................. 54

6.4.9 The Spanish contact period............................................................................... 55

6.4.10 Graves encountered in other sectors. ............................................................... 56

References .............................................................................................................................. 57

7. Human skeletal remains from El Pichao 1990 - (Preliminary

report) ................................................................................................ 58

Noemi Acreche, Museo de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Salta, Museo de

Antropologa de Salta.

Mara Gloria Colaneri, Instituto de arqueologa, Universidad nacional de Tucumn

Mara Virginia Albeza, Museo de Ciencias Naturales de Salta

References .............................................................................................................................. 61

8. Textiles en tumbas. Resultados de trabajos de campo ................... 63

Martha Ortiz Malmierca, Department of archaeology, University of Stockholm

Obras citadas .......................................................................................................................... 68

9. Geographic description of sector IX

Eduardo Ribotta, instituto de arqueloga, Universidad Nacional de Tucumn. Translated by

Sven Ahlgren and Nils Johansson

9.1 Location ........................................................................................................................... 69

9.2 Geology and geomorphology............................................................................................. 70

9.2.1 Erosion............................................................................................................. 70

9.2.2 Soils ................................................................................................................. 71

9.2.3 Phytogeography and zoogeograophy................................................................. 71

10. New approaches to the study of ceramics, El Pichao 1990

Susana Sjdin, Department of archaeology, University of Gothenburg

10.1 Introduction.................................................................................................................... 73

10.1.1 Ceramic research............................................................................................ 74

10.2 Method ........................................................................................................................... 76

10.3 The sample of El Pichao1990.......................................................................................... 78

Table 10.1 Number of sherds analysed, El Pichao 1990............................................ 78

10.3.1 Groups in the material .................................................................................... 78

References .............................................................................................................................. 85

11. Report of thin section analysis of six ceramic fragments

from El Pichao

Ole Stilborg, Department of archaeology, University of Copenhagen

11.1 Thin section analysis....................................................................................................... 87

11.2 The material ................................................................................................................... 87

11.3 Results............................................................................................................................ 88

11.3.1 Clay................................................................................................................ 88

11.3.2 Temper........................................................................................................... 89

11.3.3 Ware groups ................................................................................................... 89

11.4 Conclusions .................................................................................................................... 90

Table 11.1 Results of thin section analysis ................................................................... 91

12. The pottery of El Pichao - the process of production and

the labour processes

Susana Sjdin, Department of archaeology, University of Gothenburg

12.1 The context of the process of production ......................................................................... 93

12.2 Method ........................................................................................................................... 94

12.3 The manufacture of pottery - ethnoarchaelogical evidence............................................... 95

12.4 Conclusions concerning the process of production - archaeological evidence................... 96

12.4.1 Locally made pottery ...................................................................................... 96

12.4.2 Differentiated manufacture of ceramics........................................................... 97

12.4.3 Further differentiation of the manufacturing process of ceramics .................... 98

12.4.4 Changes of the manufacture of ceramics at the time of the Spanish

intrusion.................................................................................................................. 100

12.5 Ethnoarchaeological approaches ................................................................................... 101

12.6 Summary...................................................................................................................... 103

References ............................................................................................................................ 103

13. Approaches to room structure interpretation at El Pichao.

Two perspectives applied comparing sectors III, IV, and VIII.

Per Stenborg, Department of archaeology, Unversity of Gothenburg

13.1 Introduction.................................................................................................................. 105

13.2 Purpose........................................................................................................................ 105

13.3 Background .................................................................................................................. 106

13.4 Two main perspectives.................................................................................................. 107

13.5 A presentation of the field-data and of the methods of data-collection ........................... 108

13.5.1 The complex of structures in the northwestern part of sector III

(complex A). ........................................................................................................... 108

13.5.2 The complex of structures in sector VIII (complex B). .................................. 108

13.5.3 Unit 12. ........................................................................................................ 109

13.5.4 Unit 1. .......................................................................................................... 109

13.5.5 The problem of comparability....................................................................... 109

13.5.6 The problem of representativety.................................................................... 109

13.5.7 The question of contemporaneity .................................................................. 110

13.6 Approaching the El Pichao material in accordance with the two perspectives................ 110

13.6.1 The functionalistic/materialistic approach.................................................... 110

13.6.2 The social/symbolical approach ................................................................... 111

13.7 A description of the material, based on field-data......................................................... 112

13.7.1 The complex of structures in the northwestern part of sector III .................... 112

13.7.2 The complex of structures in sector VIII ...................................................... 115

13.7.3 Unit 12........................................................................................................ 117

13.7.4 Unit 1.......................................................................................................... 118

13.8 Analyses of the field-data............................................................................................. 118

13.8.1 The functionalistic/materialistic perspective ................................................. 118

13.8.1.1 Complex A................................................................................... 118

13.8.1.2 Complex B.................................................................................. 119

13.8.1.3 Units 1 and 12............................................................................. 119

13.8.1.4 A functionalistic/materialistic comparison between

complexes and units................................................................................... 120

13.8.2 The social, symbolical perspective ............................................................... 120

13.8.2.1 A comparison between the three groups of structures................... 120

13.8.2.2 A comparison between different parts of complex A.................... 121

13.9 Discussion and conclusions.......................................................................................... 122

13.9.1 Discussion................................................................................................... 122

13.9.2 Conclusions according to the two approaches ............................................... 123

13.9.2.1 The functionalistic/materialistic approach .................................... 123

13.9.2.2 The social/symbolical approach................................................... 124

13.9.2.3 Comments................................................................................... 124

13.10 Summary ................................................................................................................... 125

References ............................................................................................................................ 125

14. The village of El Pichao today.....................................................127

Martha Ortiz de Malmierca, Department of archaeology, University of Stockholm

References ............................................................................................................................ 129

Figures

1.1 Map of The Calchaqu Valleys

1.2 Colalao del Valle and El Pichao with the sector limitations

2.1 Distribucin de sitios Aguada

3.1 Units 1 and 2 , sector III

3.2 Structure 3, unit 1, sector III

4.1 Part of sector VIII, terrace levels 1-8, with constructions

4.2 Southeast-northwest profile of terrace levels 1-8, sector VIII

5.1 Unidad 6, sector I

5.2 Unidad 6, sector I, secciones verticales

5.3 Urna santamariana encontrada en unidad 6

6.1 Sector XI - Cemetery Amancay

6.2 Vertical section of trench 6, 6A, sector XI, Cemetery Amancay

6.3 Trenches 11-15, sector XI, Cemetery Amancay

6.4 Trench 12, sector XI, Cemetery Amancay

6.5 Trench 13, sector XI, Cemetery Amancay

El Pichao 1990

Second report from the project

Emergence and growth of centres. A case study in the

Santa Mara Valley.

Edited by

Per Cornell & Susana Sjdin

preliminary version

Department of archaeology

University of Gothenburg

September 1991

1

1. The second field campaign of the project

Per Cornell, Department of archaeology, University of Gothenburg

Susana Sjdin, Department of archaeology, University of Gothenburg

1.1 Introduction

This is a preliminary version of the second report of the project Emergence and

growth of centres in the valley of Santa Mara, NW Argentina. The project is run in

collaboration between the universities of Gotenburgh and Stockholm, Sweden, and the

National university of Tucumn, Argentina.

The project was intiated in 1989 by a pilot investigation at the site of El Pichao. The

project was made possible by the support and close collaboration with the Institute of

Archaeology, the National University of Tucumn, and its director, professor Victor

Nez Regueiro. The Swedish part of the project is in turn part of a large Argentinian

project, Estudio de la incidencia de la dinmica de interaccin entre las poblaciones

que habitaron las tierras altas y las tierras bajas . San Miguel de Tucumn 1988.

(Study of the events in the dynamic interaction between the populations that inhabited

the high lands and the low lands).

The second field season comprised excavations in different types of structures,

mappings and prospections, both of the site and its natural environments. The work was

carried out in close collaboration between Swedish and Argentinian archaeologists, and

we had also students from the Institute of Archaeology working with us. Several

specialists of different disciplines visited us during field work and made their

contributions, enriching the final results.

However, our work had not been made possible without the support and kindness we

received from the people living at the present village of El Pichao.

Rapportens innehll - bde teoreti och praktik. De argentinska deltagarna och de

svenska.

Vad som r en fortsttning av 1989 och vad som r nytt.

C-uppstaser - Per S och Cecilia

1.2 Why centre?

Per Cornell, Department of archaeology, University of Gothenburg

Why call El Pichao a centre? In the Introduction to the El Pichao 1990 report a

general definition of centre was proposed, but no specific discussion on the El Pichao

2

site was presented. I shall try to outline how I have reasoned in the specific case of El

Pichao.

First, I must say that I do not find words in themselves too important. As the

structuralists say, a signifier might be used to signify various things. the important point

is the relation between the signifiers, the structural system of - in this case - the

terminology.

However, some words attain a very special significance in cultural contexts or, as in

this case, in a scientific discourse. The word centre is a difficult one, used in many

different contexts, also within such a limited vocabulary as the archaeologists'. And it is

not just a problem of various agents' use of the word. The individual archaeologists use

the word centre in many different ways. At the same time, though, the word has become

value-laden.

What concern us here, is the use of the word centre to signify some archaeological

sites so as to show that they differ from other archaeological sites, especially

contemporaneous sites in given regions.

I have outlined some of the debate in which the word centre has been used in my Lic

treatise, and I refer the reader to this short study. Suffice it to say here that I wish to

avoid all connotations to central-place concepts and the debate of centre-periphery. This

is not to say that I find these concepts void of value. But I find it necessary to have a

good general idea of individual archaeological sites before entering such discussions.

And, in the NW Argentinian case, our knowledge of individual sites is still rather limited.

Of course, it might be argued that a general idea of greater contexts is necessary for

the understanding of the individual units. And, generally speaking, this is true. To study

individual sites we must know very much about the contexts in which they existed. But it

is equally true that we must know the individual sites in order to understand the larger

contexts. Thus, we end up in a vicious circle. To enter this circle we must choose a way

in. Lack of economic resources and the limitations of the working capacities of

individual archaeologists forces us to choose between a general survey and a more

concentrated work on a specific site.

Earlier approaches to centres have often chosen to work with general surveys. I find

that this approach has met several difficult obstacles. In the case of the Calchaqu river

system and adjoining areas, we have some general data from field surveys, even if our

knowledge is biased to some parts of the region, while others remain almost completely

unknown.

1

A present large project of the Institute of archaeology in Tucumn focuses

on the prehistoric relations between peoples living in different natural environments in

NW Argentina. In connection with this project the little known zones are studied, so

somewhat the situation will improve. Within this larger project the project Emergence

and growth of centres.... will focus on the Santa Mara Valley and especially the site of

El Pichao.

I must take a lot of things for granted. This is unavoidable, and a natural ingredient in

all scientific research. I must, above all, presuppose a certain degree of autonomity of the

individual sites.

1

Cf. for data on general surveys MYRIAM N TARRAG & PIO PABLO DAZ, Sitios arqueolgicos del

Valle Calchaqu 1-3. Estudios de arqueologa (Cachi) 1: pp 49-61 (1972); 2: pp 61-71 (1977); 3: pp

93-104 (1983), RODOLFO A RAFFINO & LIDIA N BALDINI, Sitios arqueolgicos del Valle

Calchaqu Medio. Estudios de arqueologa (Cachi) 3: pp 27-35 (1983). Specifically for the Santa

Mara valley cfInvestigaciones Arqueolgicas en el Valle de Santa Mara. Universidad Nacional del

Litoral, Facultad de Filosofa y Letras, Instituto de Antropologa, publicacin no. 4. Rosario,

Argentina 1960. Cf. also GUILLERMO MADRAZO & MARTA OTTONELLO DE GARCIA REINOSO,

Tipos de instalacin prehispanica en la region de la puna y su borde. Monografas, 1 (1966).

3

Now, we may turn to the core of the problem. I have outlined a general definition of

centre, and this definition focuses on three factors, namely size in relation to density,

existence of permanent habitations of a high relative number for the period and region,

and, finally the existence of institutional arrangements.

When discussing size/density the issue of delimitation is a difficult one. I have

proposed a somewhat unorthodox approach in the El Pichao 1989 report. This

delimitation, based on the common water source, has been used as a base for the

discussion here.

It is relatively easy to show that El Pichao matches the two first prerequisites. It is a

large site in terms of size/density in a Santa Mara valley perspective, but above all in a

larger regional perspective. According to the surveys of Raffino and Baldini in the

middle part of the Calchaqu river proper, the largest sites with extensive terracing reach

150 ha.

2

El Pichao, in a low estimate, reaches 500 ha. Even if counted by number of

habitations in relation to extension El Pichao seems to be a very large site, though at

present I cannot present data on this issue.

So, if we depart only from the first two criteria, El Pichao may be judged a centre.

But how about the third criterion?

I have consciously chosen the somewhat vague word institutional element. I wish to

avoid all direct connotations to political systems. An institutional element is not

necessarily a political element. An institutional element means, in socio-economic terms,

some sort of co-operative effort that goes beyond a few days work. It also implies a

work which cannot be done without co-operative efforts, and that requires much co-

ordination skill. The technical level may be quite similar to the work carried out by

smaller groups, but the size or character of the work gives it a new dimension.

Archaeologically, such institutional elements may be recognized as complex and, for

the period and region, large, stable, fixed constructions.

At El Pichao we have found four such types of complex arrangements. One of these

is terrace constructions including large boulders with, among other things, a cairn with

an associated large stone with petroglyfs, found in sector I. This area has been

interpreted as a ritual/religious arrangement. A second type of complex arrangement is

the large wall going through large parts of the site, running approx. E-W. A third type is

the large and complex system of terraces, probably connected to agriculture. These

cover a very large area, and if they can be shown to have been constructed in large parts

during a relatively short time span, and used contemporaneously, the scale of this system

allows us to call it a result of some institutionalised element. Both the construction and

the use, especially the irrigation, of this system must have involved dimensions far

beyond those of technically similar but smaller systems found in some other parts of the

Santa Mara Valley. It is probable that only Quilmes and Tolombn had larger areas of

terraced fields. The fourth type of institutionalised element is the disposition of different

types of habitations. If these habitations turn out contemporaneous, as is our impression

today, the clear patterning, clustering of different types implies some sort of co-

ordination.

My centre definition is not congruent with the traditional definitions. That is true. But

this is intentional.

I changed the position of the signifier, and I hope to find a new pattern. My definition

is broader than the traditional ones, and more closely linked to organizational features of

work.

The reason for the emergence of large conglomerated sites in the Santa Mara Valley

from about 1000 A.D. may be partly found in the possibilities for terracing in this area.

2

Cf. RODOLFO A RAFFINO & LIDIA N BALDINI, op cit.

4

And the cone at El Pichao may have been especially suited for such a thing. But even if

this might be a reason for the emergence of large conglomerated sites, it must have had

deep consequences, also of social character. And these socio-economic consequences of

dense conglomerated sites with complex arrangements of institutionalised character are

the main topic in the project Emergence and growth of centres - a case study in the

Santa Mara valley, NW Argentine.

In the Santa Mara valley prior to the colonial period no supra-political level is

evidently recognized among the archaeological sites. The Punta de Balasto site may have

been used as an Inca administrative centre, but it does not create the sort of sharp

contrast found in for example Huanuco in present day Peru. The Huanuco Pampa Inca

administrative site sharply contrasts against the earlier and contemporaneous sites in the

region. This same contrast between local and state levels has been found in many parts

of the world, for example at Sigirya in Sri Lanka, where local and state irrigation

systems contrasts each other (but also relate to each other).

Why this apparent weakness of possible state systems in the Santa Mara valley? The

answer may have to do with our criteria for state systems. Myrim Tarrag tries to

reconstruct the Inca road network in parts of the valley and according to her it had

impressive dimensions.

3

Rodolfo Raffino has showed, using what exists of field survey

data on the valley, that the sites show many similarities. Raffino tries to link this to the

existence of a state or chiefdom level in the area.

4

Raffino has also published, with some colleagues, data on three interesting sites SW

to the Santa Mara Valley, in the province of Catamarca. These sites all share some

architectonical traits, notably a sort of enclosed open place. The largest of these enclosed

open spaces measures about 150 x 90 m. These sites are generally interpreted as Incaic.

5

Recent studies on another similar site, Potrero Chaquiago, also located in Catamarca,

showed that the overwhelming part of the ceramic material was of local manufacture.

6

Thus, the character and meaning of these sites remains obscure.

The absence, as far as I know, of this type of sites in the Santa Mara valley shows

the differences between subregions in NW Argentine. If this absence does imply a weak

central authority or not is difficult to say. However, the weak character of the central

administrative level in the Santa Mara valley, even during the Inca period, may be a fact.

Ana Mara Lorandi has showed the difficulties the Spaniards had in trying to conquer the

valley, and Lorandi explains this partly by the absence of a central authority. The

situation may have been similar during the Inca period.

The persistence of the Santa Mara Valley sites during more than 100 years of

Spanish presence in NW Argentine is an impressive fact. During this period the sites

existed and were in some way related to Spanish cities east of the mountain range, but

they were never included in any sort of hierarchical system of sites related to the Spanish

cities.

There exist many good reasons to focus archaeological work on individual sites in the

Santa Mara Valley. I hope that the present studies at El Pichao shall allow us to make

some conclusions on the inner organization of this centre site.

3

MYRIM N TARRAG, personal communication 1990.

4

RODOLFO A RAFFINO, X. Buenos Aires 1990.

5

RODOLFO A RAFFINO, RICARDO S ALVIS, LIDIA N BALDINI, DANIEL E OLIVERA, MARIA

GABRIELLA RAVIA, Hualfin - El Shincal - Watungasta, tres casos de urbanizacin Inka en el NO

Argentino. Cuadernos del Instituto Nacional de antropologia, 10 (1983-1985, pp. 425-458.

6

ANA MARA LORANDI, MARI BEATRIZ CREMONTE & VERNICA WILLIAMS, Identificacin

etnica de los Mitmakuna instalados en el establemiento Incaico Potrero - Chaquiago. Presentado al

XI Congreso nacional de arqueologia Chilena, Santiago, 1989.

5

References

Investigaciones Arqueolgicas en el Valle de Santa Mara. Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Facultad

de Filosofa y Letras, Instituto de Antropologa, publicacin no. 4. Rosario, Argentina 1960.

LORANDI, ANA MARA, MARI BEATRIZ CREMONTE & VERNICA WILLIAMS, Identificacin

etnica de los Mitmakuna instalados en el establemiento Incaico Potrero - Chaquiago. Presentado al

XI Congreso nacional de arqueologa chilena, Santiago, 1989.

MADRAZO, GUILLERMO & MARTA OTTONELLO DE GARCIA REINOSO, Tipos de instalacin

prehispnica en la region de la puna y su borde. Monografas, 1 (1966).

RAFFINO, RODOLFO A, X. Buenos Aires 1990.

RAFFINO, RODOLFO A & LIDIA N BALDINI, Sitios arqueolgicos del Valle Calchaqu Medio.

Estudios de arqueologa (Cachi) 3: pp 27-35 (1983).

RAFFINO, RODOLFO A, RICARDO S ALVIS, LIDIA N BALDINI, DANIEL E OLIVERA, MARIA

GABRIELLA RAVIA, Hualfin - El Shincal - Watungasta, tres casos de urbanizacin Inka en el NO

Argentino. Cuadernos del Instituto Nacional de antropologia, 10 (1983-1985, pp. 425-458.

TARRAG, MYRIAM N & PIO PABLO DAZ, Sitios arqueolgicos del Valle Calchaqu 1-3. Estudios

de arqueologa (Cachi) 1: pp 49-61 (1972); 2: pp 61-71 (1977); 3: pp 93-104 (1983).

7

2. Orgenes de la ocupacin del espacio en el sitio

STucTav 5 (El Pichao)

Victor A Nez Regueiro, instituto de arqueloga, Universidad Nacional de Tucumn

Marta R A Tartusi, instituto de arqueloga, Universidad Nacional de Tucumn

2.1 Introduccin

Los trabajos de prospeccin y excavacin realizados en El Pichao durante las

campaas de 1989 y 1990 han puesto en evidencia que la mayor parte de las estructuras

observadas corresponden al lapso temporal que transcurre desde el perodo de

Desarrollos Regionales (que comienza hacia el 1000 d C) hasta el momento de la caida

de Quilmes (1665). Sin embargo se han hallado elementos que permiten afirmar que los

comienzos de la ocupacin del espacio en ese lugar arrancan desde el perodo

Formativo, posiblemente entre el 200 al 450 d C.

En este trabajo efectuaremos una aproximacin preliminar al significado de la

presencia de esos elementos en el sitio, y a la problemtica general que se deriva de las

observaciones efectuadas hasta el momento.

2.2 La periodizacin del noroeste argentino

En trabajos anteriores uno de nosotros propuso una periodizacin del noroeste

argentino

7

sobre la cual se ha basado la terminologa utilizada en el informe sobre los

trabajos de excavacin en El Pichao de 1989.

8

En ese esquema, el perodo Formativo era

dividido en inferior, medio y superior, el segunda de los cuales estaba caracterizado por

la cultura Aguada.

Actualmente hemos introducido una modificacin conceptual y terminolgica, que

emplearemos en este trabajo, porque expresa sintticamente los principales cambios que

se registran en el desarollo de la regin Valliserrana.

Al trmino Formativo lo reservamos para el perodo que habiamos denominado

Formativo inferior, y utilizamos el de Integracin regional para los que antes llambamos

7

VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO, Conceptos instrumentales y marco terico en relacin al anlisis del

desarollo cultural del noroeste argentino. Revista del instituto de antropologa 5, Crdoba 1974, pp

169-170; VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO, Considerations on the periodization of Northwest

Argentina. Advances in Andean archaeology (ed D L Browman). The Hague 1978, pp 451-484.

8

SUSANA SJDIN, The traditional periodization and ceramic classification. El Pichao 1989. The first

report from the project Emergence and growth of centres. A case study in the Santa Mara Valley in

the Andes (prel version). (eds P Cornell & S Sjdin, Gothenburg University, Department of

archaeology, unpubl, Gteborg 1990), pp 11-13.

8

Formativo medio.

9

Sintticamante podemos decir que la razn de este cambio es que

consideramos que Aguada es el resultado de la conjuncin de dos sistemas provenientes

del Formativo. (...) uno de origen andino-altiplnico, basado en la domesticacin de

camlidos y el cultivo de la papa; otro, de origen en las tierras bajas y el piedemonte

oriental, basado en la agricultura del maz (...), y representa lo que podemos considerar

como un momento de integracin regional.

10

Esto ltimo ya habia sido planteado por

Lumbreras, quien al referirse al perodo que nos ocupa, dice: Parece ser un perodo de

integracin regional (...).

11

2.3 Problemas para la identificacin de sitios Formativos y de Integracin

regional

En muchos sitios arqueolgicos, la existencia de una cultura se ha inducido

bsicamente sobre la presencia de cermica y secundariamente, otros elementos, hallados

en superficie o en excavaciones, sin que se registren construcciones habitacionales. Las

excavaciones a las que hacemos referencia se han solido circunscribir a pruebas

estratigrficas y a tumbas. Un buen ejemplo para el noroeste Argentino lo constituye la

cultura Condorhuasi. Condorhuasi slo tiene contexto propio en tumbas, de ah que no

se pueda asociarlo a ningn tipo de patrn de instalacin ni a una determinada

economa.

12

Los sitios del Campo del Pucar (Dpto Andalgal, Provincia de Catamarca) slo son

reconocibles por la existencia de una serie de montculos que forman un anillo, a veces a

penas sobreelevado respecto al terreno circundante. En ocasiones los montculos,

adems de ser reconocibles por su forma, lo son por la existencia de algunas piedras que

afloran en superficie, indicando la presencia de las columnas de piedra que integran las

paredes de barro.

13

En los sitios de Campo del Pucar, que han sido descriptos como de Alamito o

Alumbrera por hallarse cerca de esas localidades, son caractersticas dos plataformas

rectangulares, de paredes de piedra, que afloran sobre el terreno, facilitando su

localizacin. Pero hay en esa zona, como excepcin, en el sector correspondiente a los

1900 msnm, sitios que carecen de esta modalidad, por hallarse las plataformas

9

La fundamentacin de este cambio se halla expuesta en VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO Y MARTA R A

TARTUSI, El rea Pedemontana y su significacin para el desarollo del noroeste argentino, en el

contexto sudamericano. Ponencia presentada en el 46

o

Congreso internacional de americanistas,

Amsterdam 1988; y en VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO Y MARTA R A TARTUSI, Aproximacin al

estudio del rea pedemontana de sudamrica. Cuadernos del instituto nacional de antropologa, 12.

Buenos Aires 1990.

10

VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO Y MARTA R A TARTUSI, op cit, 1988.

11

LUIS GUILLERMO LUMBRERAS, Arqueologa de la America Andina. Lima 1981, p 99.

12

MARTA M OTTONELLO Y ANA MARIA LORANDI, Introduccin a la arqueologa y etnologa. Diez

mil aos de historia argentina. Buenos Aires 1987.

13

VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO, The Alamito culture of Northwestern Argentina. American Antiquity,

35 (1970), pp 135-140; VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO, La cultura Alamito de la subrea Valliserrana

del noroeste argentino. Journal de la Socit des Amricanistes, 60 (1971), pp 7-64.

9

completamente cubiertas por sedimentos. Esto se repite en sitios existentes en la parte

meridional del Campo en las proximidades de Agua de las Palomas.

14

En el valle de Ambato resulta clara la existencia de una continuidad histrica y

cultural con el Campo del Pucar,

15

tanto a nivel ceramolgico (p ej la perduracin e

incremento de Alumbrera tricolor) como constructivo, donde perdura la tcnica de

paredes de barro con columnas de piedra. Es decir, subsiste en el perodo de Integracin

regional, manifestado en Ambato, el problema de la dificultad de reconocimiento de

muchas estructuras.

La dificultad, e incluso, la imposibilidad de reconocimiento de construcciones de los

perodos Formativo y de Integracin regional vara considerablemente segn las zonas,

de acuerdo a la forma en que han operado a lo largo del tiempo los factores naturales, en

especial la sedimentacin, la erosin y la cubierta vegetal.

A los procesos naturales mencionados deben sumarse los factores antrpicos. Las

poblaciones instaladas en las zonas donde existen sitios arqueolgicos, como es el caso

de El Pichao, frecuentemente destruyen recintos prehispnicos con el objeto de utilizar el

material de las pircas o paredes de piedra, para edificar viviendas, cercos y corrales.

Otras construcciones, como los antiguos andenes, son reutilizadas y adaptadas a las

necesidades que tienen actualmente los habitantes de la zona.

Este proceso de destruccin parcial o total de las ruinas arqueolgicas, o de

modificacin impuesta por la necesidad de adaptacin a nuevos usos, no se halla

restringido a la actualidad.

En los sitios arqueolgicos que han sido ocupados durante largos perodos, es normal

que la construccin de nuevas estructuras, o la modificacin o reparacin de estructuras

en uso, hayan ido alterando las construcciones antiguas. Incluso, la necesidad de

readaptar el espacio a las nuevas necesidades sociales, y la conveniencia que implica el

ahorro de energa, pueden hacer desaparecer por completo las obras anteriormente

realizadas. La reutilizacin de la piedra de construcciones en desuso para le edificacin

de nuevas obras, significa un importante ahorro de tiempo y esfuerzo, mximo cuando la

materia prima ha sido escogida o preparada especialmente, como ocurre con las piedras

canteadas. Esto hace que, tal como sucede con las glaciaciones, sea ms fcil estudiar un

fenmeno caunto ms reciente es, debido a que cada nuevo acontecimiento borra,

aunque sea parcialmente, los rastros dejados por el anterior. Cuanto ms nos alejamos en

el tiempo, ms dificil resulta hallar evidencias que nos permitan reconstruir el pasado.

El espacio que ocupaban los sitios del Campo del Pucar, una vez abandonado, no ha

vuelto a ser utilizado por poblaciones prehispnicas posteriores. Lo mismo ocurre en el

valle de Ambato con los sitios del perodo de Integracin regional. En un yacimiento

como el de El Pichao, que manifiesta una continuidad temporal desde el Formativo hasta

el perodo Hispano-Indgena, a los factores de perturbacin naturales se le han sumado

los procesos antrpicos producidos por una intensa y temporalmente larga ocupacin del

espacio.

Todo esto hace que, hasta el momento, sean los artefactos (de piedra y de cermica)

los nicos indicios que disponemos para detectar la presencia de entidades

14

ALBERTO REX GONZLEZ & VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO, Apuntes preliminares sobre la

arqueologa del Campo del Pucar y alrededores (Dpto Andalgal, Pcia Catamarca). Anales de

Arqueologa y Etnologa, 14-15, (Mendoza 1960), pp 115-162.

15

VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO, El problema de la periodificacin en arqueologa. Actualidad

antropolgica, 16 (Olavarra 1975), pp 1-20; JOS A PEREZ & OSVALDO R HEREDIA,

Investigaciones arqueolgicas en el Departamento Ambato, provincia de Catamarca. Relaciones de

la sociedad argentina de antropologa, 9 (Buenos Aires 1975), pp 59-68; VICTOR NEZ

REGUEIRO & MARTA R A TARTUSI, Aproximacin al estudio del arte Predemontana de

Sudamrica. Cuadernos del instituto nacional de antropologa, 12 (Buenos Aires 1990).

10

socioculturales anteriores al perodo de Desarollos regionales en El Pichao. Decimos

hasta el momento, porque se han constatado superposicin de estructuras en algunas

trincheras y pozos de exploracin, que abren nuevas perspectivas en este sentido, a nivel

de excavacin.

2.4 Ocupacin del espacio en El Pichao

2.4.1El perodo Formativo en El Pichao

La posibilidad de hallar en El Pichao vestigios de la ocupacin del espacio desde el

Formativo habia sido prevista sobre la base del anlisis bibliogrfico. Quiroga describe

un (...) dolo 298, de piedra, de Colalao del Valle, que es un almirez [mortero] en su

forma, teniendo en la parte de sujetarlo para moler, la cara de un animal extrao.

16

A

este objeto, que por la descripcin debe corresponder al Formativo, lo compara con

otros, similares segn el, provenientes de otros lugares de la provincia de Tucumn

(Amaicha, Taf) y de las provincias de Catamarca y Salta.

La prueba de la presencia de entidades formativas en la zona de El Pichao la

constituyen: un recipiente de andesita, hallado a aproximadamente a un kilmetro al

oeste de la localidad de Colalao del Valle por un poblador de la zona; y dos fragmentos

de recipientes similares, tambin encontrados en superficie por habitantes del lugar. A

uno de ellos se lo localiz en el Sector II de El Pichao, en las proximidades de la actual

cancha de ftbol construda en pleno yacimiento; al otro. cerca del puente Dr Arturo

Illia, emplazado sobre la ruta que une al El Pichao con Colalao del Valle.

La tcnica de percusin sin pulimentacin utilizada para construir los recipientes, la

forma, el tamao, y en el caso del ejemplar hallado completo, la decoracin, no dejan

dudas acerca de su filiacin cultural.

En sitios de Campo del Pucar, pertenecientes a la cultura Alamito-Condorhuasi, se

han ahllado ejemplares en un todo parecidos a los que aqu mencionamos, tanto en sitios

correspondientes a la Fase I de esa cultura (200-350 d C) como a la Fase II (350-450 d

C).

17

Los ejemplares del Campo del Pucar se hallaron en asociacin con reas

ceremoniales y de trabajo (cobertizos), nunca dentro de habitaciones; en un caso,

como ajuar fnebre en un entierro directo de adulto correspondiente a la Fase II.

18

Adems de esos recipientes, se han hallado en El Pichao algunos fragmentos de

cermica gris pulida, sin decoracin, o decorada con lneas incisas finas y paralelas que

forman a veces parte de elementos decorativos con sombreado zonal (zoned hachure),

que corresponden a tipos caractersticos del Formativo. Por su factura y decoracin

podran ubicarse dentro del conjunto de tipos cermicos que tradicionalmente han sido

reconocidos como Cinaga.

16

ADN QUIROGA, Antigedades Calchaques. La coleccin de Zavaleta. Boletn del Instituto

Geogrfico Argentino, 17 (Buenos Aires 1896), p 27.

17

VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO, La cultura Alamito de la subrea Valliserrana del noroeste argentino.

Journal de la Socit des Amricanistes, 60 (1971), pp 7-64.

18

Este recipiente figura como mortero en VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO, Excavaciones arqueolgicas en

la unidad D-1 de los yacimientos de Alumbrera (1964) (Zona de El Alamito), Dpto Andalgal, Pcia

de Catamarca, Repblica Argentina. Anales de Arqueloga y Etnologa 24-25 (Mendoza 1971), pp

33-76.

11

Los fragmentos mencionados han sido obtenidos en recolecciones de superficie,

especialmente en el sector I, y en excavaciones, como las realizadas en la unidad 6 de

dicho sector (ver informe en esta obra). Su frecuencia es muy reducida; en la unidad 6 y

en las recolecciones de superficie adyacentes a la misma, el porcentaje de los fragmentos

gris pulido sobre el total de la muestra vara entre 0.97 y 2.74; y el de los incisos entre

0.30 y 0.93.

En las excavaciones de la unidad 4 del sector I fue hallado un fragmento de tubo de

pipa de cermica gris pulida.

No se han ubicado estructuras que puedan adscribirse al perodo que estamos

tratando.

2.4.2 El perodo de Integracin regional en El Pichao

En recolecciones de superficie efectuadas en El Pichao especialmente en el sector I,

han aparecido fragmentos de cermica Aguada, tanto pintados como grabados, aunque

en muy bajas proporciones. Estilsticamente comparten rasgos caractersticos de la

cermica Aguada que Gonzlez ha denominado del Sector Septentrional

19

o Aguada

sensu stricto.

20

Al igual que en el caso del Formativo, no se han hallado aqu estructuras

que puedan identificarse con el perodo que nos ocupa.

Debemos tener en cuenta las observaciones que hemos apuntado anteriormente,

respecto a las dificultades que entraa la localizacin de sitios correspondientes tanto al

perodo Formativo como al de Integracin regional.

La presencia de cermica Aguada en El Pichao hace que debamos incluir a este sitio

dentro de la problemtica general que Aguada representa para la arqueologa del

noroeste Argentino.

A este respecto cabe sealar que al hablar de Aguada, no hemos utilizado el trmino

cultura por cuanto consideramos que (...) Aguada no es una cultura que se implanta

sobre una rea extensa, sino la manifestacin de una integracin regional resultando de la

interaccin de culturas del Formativo (...) de distinto origen, que alcanza a tener un

denominador comn a nivel de superestructura.

21

2.5 El significado de la ocupacin del espacio para el anlisis de la

problemtica Aguada

La distribucin de Aguada, tomando como base la bibliografa disponible, los

materiales existentes en el Instituto de arqueloga de la UNT, y las prospecciones que

hemos realizado, abarca en Argentina desde el Departamento Cachi (Pcia de Salta) al

19

ALBERTO REX GONZLEZ, Arte Precolombino de Argentina. Introduccin a su historia cultural.

Buenos Aires 1977.

20

ALBERTO REX GONZLEZ, Las poblaciones autctonas de Argentina. Races Argentinas 3-4.

Crdoba 1982.

21

VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO Y MARTA R A TARTUSI, El area Pedemontana y su significacin para

el desarollo del noroeste argentino, en el contexto sudamericano. Ponencia presentada en el 46

o

Congreso internacional de americanistas, Amsterdam 1988.

12

norte, hasta el norte de la Provincia de San Juan, por el sur (ver mapa de la Figura

2:1).

22

Berenguer publica la descripcin de un cesto campanuliforme bordado y una

figurilla femina de madera, que atribuye a Aguada, provenientes de Coyo Oriente, en la

zona de San Pedro de Atacama (Norte de Chile) [1].

23

Esto, segn ese autor lo seala,

extendera la presencia de Aguada hasta esa zona, tal como haba sido enunciado por

Gonzlez.

24

En los valles y quebradas ocupados por la tradicin Taf (valles de Taf y la Cinaga,

y Quebrada del Portugus; Pcia de Tucumn)

25

que de acuerdo a las dataciones

radiocarbnicas se desarolla desde el siglo IV a C

26

hasta el siglo IX d C.

27

Resulta clara

la interrelacin de Taf con la tradicin Candelaria a lo largo de toda la secuencia. Sin

embargo, no se ha registrado aqu la presencia de Aguada.

Aguada se halla presente en el sector tucumano del valle de Santa Mara en sitios

que, como El Pichao [15], se ubican en el borde oriental de las sierras del Cajn o de

Quilmes [14 a 16], y se extiende hacia la ladera occidental de las Cumbres Calchaques,

llegando a la zona de Amaicha [17]. Aparentemente no traspone las cumbres hacia los

valles ocupados por Taf, como podra haberlo hecho por las abras del Infiernillo y de las

Animas. El paso utilizado para llegar a la zona de San Pedro de Colalao [13] debi ser

un poco ms al norte (Figura 2:1).

En la zona del piedemonte oriental y la llanura adyascente que corre desde San Pedro

de Colalao hasta el Departamento Alberdi, no se han registrado sitios Aguada, sino solo

Candelaria. A partir de Alberdi, Aguada contina distribuyndose hacia el sur [25 a 29].

22

Los sitios identificados como Aguada por la presencia de cermica se indican con un crculo relleno;

los identificados por arte rupestre, son una U invertida sobre un crculo relleno; el identificado por

fragmentos cermicos y objetos no cermicos, fuera de Argentina, por un crculo relleno inscripto en

un cuadrado.

En este mapa se corrige la ubicacin de algunos sitios mal registrados en la Foto 2 de RODOLFO

RAFFINO et al, La expansin septentrional de la cultura La Aguada en el N O argentino.

Cuadernos del Instituto Nacional de antropologa, 9 (Buenos Aires 1982), pp 7-35; y el mapa II,

figura 3.4 de RODOLFO RAFFINO, Poblaciones indgenas en Argentina, urbanismo y proceso social

precolombino. Buenos Aires 1988, como el de Molino del Pusto, que se halla situado a 2 km al norte

de Santa Mara (Pcia de Catamarca), EDUARDO MARIO CIGLIANO et al, Molino del Puesto.

Investigaciones arqueolgicas en el valle de Santa Mara. Instituto de antropologa, publicacin 4,

Rosario 1960, pp 11-119; y en los mapas de Raffino se lo ubica al norte de El Pichao (Pcia de

Tucumn). Adems, se han agregado nuevos sitios.

Para faciltiar su ubicacin en el mapa, en el texto, cuando se cita un sitio, se le coloca a continuacin,

entre corchetas [], el nmero que le corresponde en el mapa.

23

JOS BERENGUER R, Hallazgos la Aguada en San Pedro de Atacama, Norte de Chile. Gaceta

Arqueolgica Andina 12 (Lima 1988), pp 12-14.

24

ALBERTO REX GONZLEZ, Las tradiciones alfareras del Perodo Temprano del N O argentino y sus

relaciones con las de las reas aledaas. Anales de la universidad del Norte 2 (Santiago 1963), pp

49-65; La cultura de la Aguada el N O argentino. Revista del instituto de antropologa, 2-3

(Crdoba 1964), pp 205-253; ALBERTO REX GONZLEZ & JOS ANTONIO PREZ, Argentina

indgena, vsperas de la conquista. Buenos Aires 1972.

25

ALBERTO REX GONZLEZ & VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO, Preliminary report on archaeological

research in Taf del Valle, N W Argentina. Akten des 34 Internationalen Amerikanistenkongresses.

Wien 1960, pp 485-496; MARA T BERNASCONI DE GARCA & ANA NLIDA BARAZA DE FONTS,

Estudio arqueolgico del Valle de la Cinaga (departamento de Taf, Provincia de Tucumn).

Anales de arqueologa y etnologa 35-37 (Mendoza 1985), pp 117-138.

26

ALBERTO REX GONZLEZ, Nuevas fechas de la cronologa argentina obtenida por el mtodo del

radiocarbn (V). Revista del instituto de antropologa 2-3 (Crdoba 1965), pp 289-297, pp 290-

292.

27

EDUARDO BERBERIAN et al, Sistemas de asentamientos prehispnicos en el valle de Taf. Crdoba

1988, pp 15-17.

13

Los valles de Taf y de la Cinaga, y la Quebrada del Portugus, la va ms fcil de

acceso a la llanura tucumana desde el valle de Taf, constituyen un hiato geogrfico que

nos est marcando una clara frontera a nivel de interaccin cultural.

El tema de la existencia de fronteras tiene como complemento espacial el de la

territorialidad. Si existen fronteras de interaccin es porque existen territorios o espacios

no compartidos, claramente definidos.

Si nos remitimos al mapa de la Figura 2:1, observamos que hay dos grupos de arte

rupestre identificables como Aguada por los elementos representados. Uno se halla

marcando el extremo norte de la distribucin de Aguada en Argentina; el otro, marcanda

el borde sudoriental de la misma. El primero de los grupos nombrados [2] lo constituyen

petroglifos, an inditos, localizados en el valle Calchaqu, en el sitio SSalCac 69, El

Diablo,

28

que hemos tenido oportunidad de relevar; el otro [46, 47], ya conocido a

travs de la bibliografa, es el de las pictografas de la Sierra de Ancasti.

29

Aparte de su posible significado mgico-religioso, las manifestaciones de arte

rupestre de Aguada podran tener sentido a nivel de territorialidad, como expresin de

una organizacin socio-politica ms compleja y estructurada de lo que habamos

previsto. Gonzlez haba sealado con claridad, refirindose a Aguada, que:

El sistema de simple organizacin tribal, pudo estar superado aqu por el del seoro o reunin de

un cierto nmero de tribus bajo una sola autoridad.

30

Tal vez Aguada haya constituido un verdadero seoro originado por la dinmica de

interaccin entre Alamito-Condorhuasi y Cinaga, que dio como resultado la integracin

de los dos sistemas socioeconmicos y culturales a los que hicimos referencia con

anterioridad. La religin habra actuado como elemento aglutinador a nivel de

superestructura, sobre pueblos de origen distinto, confirindose cierta homogeneidad

reflejada en los aspectos iconogrficos y religiosos. No resulta dificil pensar que en estas

circunstancias, la existencia de fronteras como la que representaba la tradicin Taf con

la conjuncin de Candelaria, hubiera sido un elemento positivo para la consolidacin de

la centralizacin de la autoridad en Aguada.

La ocupacin del espacio por parte de Aguada nos lleva, tomando en cuenta tambin

otros indicadores, a reforzar la idea de la complejidad del perodo de Integracin

regional.

Los sitios Aguada se ubican generalmente en los valles del noroeste, entre los 1000 y

3000 m s n m, y con menor frecuencia en el piedemonte oriental y la llanura prxima.

Estos ltimos [25 a 29, 40 a 48, 90 a 96] forman como una angosta y larga frontera

oriental, ecolgicamente diferenciada en forma clara de las restantes zonas de ocupacin.

La mayor parte del rea ocupada por Aguada se manifiesta como un espacio bastante

continuo, a excepcin de un sitio que queda aislado y en altitud extrema, en la Puna, en

las proximidades del Salar de Antofagasta [101], por encima de los 4000 m s n m. La

distribucin de sitios Aguada ocupando lugares tan distintos, est indicando la existencia

de asentamientos ubicados en diferentes ambientes ecolgicos, en funcin de la explota-

28

PIO PABLO DIAZ, Arte rupestre en Valle Arriba. Estudios de arqueologa 3-4 (Salta 1983), pp 9-25.

29

NICOLS DE LA FUENTE & ADN ROBERTO DIAZ MORENO, Algunos motivos del arte rupestre de

la zona de Ancasti (provincia de Catamarca). Miscelnea de arte rupestre de la Repblica Argentina

(ed Lidia C Alfaro de Lanzone et al). Monografas de arte rupestre, arte americano 1. Barcelona

1979, pp 37-59; NICOLS DE LA FUENTEet al, Nuevos motivos de arte rupestre en la sierra de

Ancasti, provincia de Catamarca. Dos objetos de metal prehispnicos del valle de Catamarca..

Universidad nacional de Catamarca, Departamento de educacin. Catamarca 1982, pp 13-45.

30

ALBERTO REX GONZLEZ, Arte precolombina de la Argentina, introduccin a su historia cultural.

Buenos Aires 1977, p 179.

14

cin de recursos especficos. Pensamos que el intercambio y los principios fundamentales

de la organizacin socio-econmica de las sociedades andinas (...) la reciprocidad, la

redistribucin y el control vertical de la ecologa

31

, son mecanismos cuyo estudio

debe profundizarse para poder comprender en forma integral la problemtica Aguada.

Estos mecanismos deben haber funcionado, en Aguada, sobre la base de una red mucho

ms compleja que la que oper en el perodo anterior, desempeando un papel de gran

importancia el trfico caravanero, cuyo desarollo debe buscarse desde el Formativo, y

cuya importancia para las sociedades prehispnicas han sido sealadas con claridad por

arquelogos chilenos.

Obras citadas

ALBERTI, GIORGIO & ENRIQUE MAYER, Reciprocidad andina: ayer y hoy. Reciprocidad e

intercambio en los Andes peruanos (eds G Alberti & E Mayer). Instituto de estudios peruanos. Lima

1974, pp 13-33.

BERBERIAN, EDUARDO et al, Sistemas de asentamientos prehispnicos en el valle de Taf. Crdoba

1988, pp 15-17.

BERENGUER R, JOS, Hallazgos la Aguada en San Pedro de Atacama, Norte de Chile. Gaceta

Arqueolgica Andina, 12 (Lima 1988), pp 12-14.

BERNASCONI DE GARCA, MARA T & ANA NLIDA BARAZA DE FONTS, Estudio arqueolgico del

Valle de la Cinaga (Departamento de Taf, Provincia de Tucumn). Anales de arqueologa y

etnologa 36-37, (Mendoza 1985), pp 117-138.

CIGLIANO, EDUARDO MARIO et al, Molino del Puesto. Investigaciones arqueolgicas en el valle de

Santa Mara. Instituto de antropologa, publicacin 4, (Rosario 1960), pp 111-119.

DE LA FUENTE, NICOLS & ADN ROBERTO DIAZ MORENO, Algunos motivos del arte rupestre de

la zona de Ancasti (Provincia de Catamarca). Miscelnea de arte rupestre de la Repblica

Argentina (eds L C Alfaro de Lanzone et al). Monografas de arte rupestre, arte americano 1.

Barcelona 1979, pp 37-59.

DE LA FUENTE, NICOLS et al, Nuevos motivos de arte rupestre en la sierra de Ancasti, provincia de

Catamarca. Dos objetos de metal prehispnicos del valle de Catamarca.. Universidad nacional de

Catamarca, Departamento de educacin. Catamarca 1982, pp 13-45.

DIAZ, PIO PABLO, Arte rupestre en Valle Arriba. Estudios de arqueologa, 3-4 (Salta 1983), pp 9-25.

GONZLEZ, ALBERTO REX, Las tradiciones alfareras del Perodo Temprano del N O argentino y sus

relaciones con las de las reas aledaas. Anales de la universidad del Norte, 2 (Santiago 1963), pp

49-65.

GONZLEZ, ALBERTO REX, La cultura de la Aguada el N O argentino. Revista del instituto de

antropologa, 2-3 (Crdoba 1964), pp 205-253.

GONZLEZ, ALBERTO REX, Nuevas fechas de la cronologa argentina obtenida por el mtodo del

radiocarbn (V). Revista del instituto de antropologa, 2-3 (Crdoba 1965), pp 289-297.

GONZLEZ, ALBERTO REX, Arte Precolombina de Argentina. Introduccin a su historia cultural.

Buenos Aires 1977.

GONZLEZ, ALBERTO REX, Las poblaciones autctonas de Argentina. Races Argentinas, 3-4.

Crdoba 1982.

GONZLEZ, ALBERTO REX & VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO, Apuntes preliminares sobre la

arqueologa del Campo del Pucar y alrededores (Dpto Andalgal, Pcia Catamarca). Anales de

Arqueologa y Etnologa, 14-15, (Mendoza 1960), pp 115-162.

GONZLEZ, ALBERTO REX & VICTOR NEZ REGUEIRO, Preliminary report on archaeological

research in Taf del Valle, N W Argentina. Akten des 34 Internationalen Amerikanistenkongresses.

Wien 1960, pp 485-496.

31

GIORGIO ALBERTI & ENRIQUE MAYER, Reciprocidad andina: ayer y hoy. Reciprocidad e

intercambio en los Andes peruanos (eds Giorgio Alberti & Enrique Mayer). Instituto de estudios

peruanos. Lima 1974, pp 13-33, p 15.

15

GONZLEZ, ALBERTO REX & JOS ANTONIO PREZ, Argentina indgena, vsperas de la conquista.

Buenos Aires 1972.

LUMBRERAS, LUIS GUILLERMO, Arqueologa de la America Andina. Lima 1981.

NEZ REGUEIRO, VICTOR, The Alamito culture of Northwestern Argentina. American Antiquity,

35 (1970), pp 135-140.

NEZ REGUEIRO, VICTOR, La cultura Alamito de la subrea Valliserrana del noroeste argentino.

Journal de la Socit des Amricanistes, 60 (Paris 1971), pp 7-64.

NEZ REGUEIRO, VICTOR, Excavaciones arqueolgicas en la unidad D-1 de los yacimientos de

Alumbrera (1964) (Zona de El Alamito), Dpto Andalgal, Pcia de Catamarca, Repblica

Argentina. Anales de Arqueloga y Etnologa 24-25, (Mendoza 1971), pp 33-76.

NEZ REGUEIRO, VICTOR, Conceptos instrumentales y marco terico en relacin al anlisis del

desarollo cultural del Noroeste argentino. Revista del instituto de antropologia , 5, (Crdoba 1974),

pp 169-170.

NEZ REGUEIRO, VICTOR, El problema de la periodificacin en arqueologa. Actualidad

antropolgica, 16 (Olavarra 1975), pp 1-20.

NEZ REGUEIRO, VICTOR, Considerations on the periodization of Northwest Argentina. Advances

in Andean archaeology (ed D L Browman). The Hague 1978, pp 451-484.

NEZ REGUEIRO, VICTOR & MARTA R A TARTUSI, El rea Pedemontana y su significacin para el

desarollo del Noroeste argentino, en el contexto sudamericano. Ponencia presentada en el 46

o

Congreso internacional de americanistas, Amsterdam 1988.

NEZ REGUEIRO, VICTOR & MARTA R A TARTUSI, Aproximacin al estudio del rea

Pedemontana de Sudamrica. Cuadernos del Instituto nacional de antropologa, 12 (Buenos Aires

1990).

OTTONELLO, MARTA M & ANA MARIA LORANDI, Introduccin a la arqueologa y etnologa. Diez

mil aos de historia argentina. Buenos Aires 1987.

PEREZ, JOS A & OSVALDO R HEREDIA, Investigaciones arqueolgicas en el Departamento Ambato,

provincia de Catamarca. Relaciones de la Sociedad argentina de antropologa, 9 (Buenos Aires

1975), pp 59-68.

QUIROGA, ADN, Antigedades Calchaques. La coleccin de Zavaleta. Boletn del Instituto

Geogrfico Argentino 17 (Buenos Aires 1896).

RAFFINO, RODOLFO A, Poblaciones indgenas en Argentina, urbanismo y proceso social

precolombino. Buenos Aires 1988.

RAFFINO, RODOLFO A et al, La expansin septentrional de la cultura La Aguada en el N O

argentino. Cuadernos del Instituto Nacional de antropologa, 9 (Buenos Aires 1982), pp 7-35.

SJDIN, SUSANA, The traditional periodization and ceramic classification. El Pichao 1989. The first

report from the project Emergence and growth of centres. A case study in the Santa Mara Valley in

the Andes (eds P Cornell & S Sjdin, University of Gothenburg, Gteborg 1990, prel version), pp

11-13.

17

3. Unit 1 as a household and the 1990 excavations in

structure 3

Per Cornell, Department of archaeology, University of Gothenburg

3.1 Unit 1

Unit 1 is situated in sector III. The unit consists of a large structure measuring

approx. 28 x 21 m, and some smaller structures linked to the large one. The ceramic

material may, on stylistic grounds, and related to the traditional Argentinian ceramic

chronology, date the structure to somewhere between 1300 and 1550 A.D.

The relative age of the different structures cannot be estimated at present. I will,

however, presuppose that, at least during some phase, all the structures has had some

contemporaneous use. In the following I will try to describe the different structures and

try to trace the occupational history of each individual structure.

I will consider Unit 1 as a household. Before entering the description of the

archaeological material, I must therefore make a short discussion on the concept of

household.

3.2 What is a household?

3.2.1 The household as a general concept

At a closer look household is a quite complex term. As a general concept in

economic theory household is a unit within which a set of individuals is housed and fed,

and in which elders and children as well as the so-called active population is

integrated. Household activity is then contrasted to gainful activity, e. g. activities

aiming at a money income. Thus defined households have existed in many societies in

many different periods.

32

This thus should be a world of pure subsistence, and corresponding activities should

be production of food, production of necessary utensils, cooking, cleaning, and caring of

children and the sick. But even if many types of households may be said to have certain

basic subsistence functions that simply define the concept, they articulate in different

ways, and the existence of household with few elements of non-subsistence function

must be taken into consideration.

32

This is the definition used in many traditional textbooks on political economy of the type of Adam

Smith.

18

The quoted general definition of household was, however, used by Marshall Sahlins

in his work Stone age economics, in the discussion on the Domestic mode of production

(DMP). According to Sahlins, households is the original type of social organisation.

These units were autonomous and produced themselves the main part of the products

necessary for survival. Further, Sahlins described these units in the words of Chayanov, a

Russian neo-classical (formalist) economist: each household strives to minimize the work

for each member. If the working power of a household is enlarged, this enlargement is

used to lower the amount of work of each member, not to intensify production. And

such units avoid socio-political organisation, they flee. Thus Sahlins tries to find

exclusively political factors as provoking structural change.

33

Claude Meillasoux has a similar approach. He uses a term similar to that of Sahlins,

and describes the household as a unit of reproduction. By this he means that the

household strives to feed and care for its active members, the elders and the children,

and that this is the function of the household. According to Meillasoux, working with

West African examples, the political development thus took place outside the

households.

34

Like Emmanuel Terray,

35

Meillasoux sees the state apparatus as an

external phenomenon, based mainly on slavery. The slave has the advantage, from the

slave-owner's point of view, not to be integrated in a household, thus only one active

person must be fed, instead of a whole household unit.

36

These definitions of the household are basically similar to the concept of an asiatic

mode of production, as envisaged by Ferenc Tkey. Ferenc Tkey, an Hungarian

sinologist, departed from Karl Marx' old Asiatic mode of production thesis. He states

that the Asiatic societies have a stagnant character. The character of these societies is

such that autonomous peasant villages co-exist with a state that is purely political in

character, a state that does not engage itself in production. The villages are autonomous

and self-sufficient in their internal organisation, only subject to taxation by the state

according to Tkey. The stagnation is due to the lack of interest of the state in direct

production, coupled with the small interest peasants show in expanding their production,

knowing that all their surplus will be taxed away, writes Tkey.

37

The concept of the redistributive state as envisaged by Karl Polanyi partly followed

the same lines, but it stressed the state involvement at the level of distribution.

38

In the

evolutionary sequence of Richard Thurnwald, which was a point of departure for

Polanyi, the all-embracing redistributive state is seen as the last phase in a sequence

initiated by nomadic tribes that established a state and ruled over agricultural groups.

39

I

doubt that this ideal state has ever existed, and if so only in some few isolated cases.

Redistributive feasts obviously have been important,

40

and in some situations food has

been redistributed in connection with catastrophies. However, the extent of this last

33

MARSHALL SAHLINS, Stone age economics. New York 1972.

34

CLAUDE MEILLASOUX, Maidens, meal and money (1975). Cambridge 1988.

35

Cf. EMMANUELTERRAY, La captivit dans le royaume abron du Gyaman. L'esclavage en Afrique

prcoloniale (Claude Meillasoux, ed.). Paris 1975, pp. 384-453 and EMMANUEL TERRAY Gold

production, slave labor, and state intervention in precolonial Akan societies: a reply to Raymond

Dummett. Research in economic anthropology, vol. 5, Greenwich, Conn., 1983, pp. 95-129.

36

CLAUDE MEILLASOUX, Anthropologie de l'esclavage. Le ventre de fer et d'argent. Paris 1986.

37

FERENC TKEY, Essays on the asiatic mode of production (1960). Budapest 1979.

38

KARL POLANYI, The great transformation, New York 1944.

39

RICHARD THURNWALD, Die menscliche Gesellschaft, 3: Werden, Wandel und gestaltung der

wirtschaft. Berlin 1932.

40

Craig Morriss has stressed this point in relation to Inca economy at Hunuco Pampa, cf CRAIG

MORRIS, The infrastructure of Inka control in the Peruvian central highlands. The Inca and Aztec

states 1400-1800, New York 1982, pp. 153-171.

19

phenomenon is not clear. It is interesting that Bronislaw Malinowski in the Argonauts of

the western pacific wrote that food was plenty at the Trobriands and that part of it was

let to rot, while he later in Coral Gardens and their magic writes that hunger

catastrophies were far from rare and that the headmen and their relatives survived better

than others in such connection, since they had more food stored.

41

A more interesting approach in the study of the early state, especially the Andean, is

that of John V Murra.

42

Murra considers the conscription of members of households, or

whole households, to have been the backbone of the Inca empire. He has also discussed

the use of, and occupations in, different natural zones, and its relation to conscript

labour. Still our knowledge is very partial and subject to intensive debate. However, If

we provisionally accept the thesis of Murra as a fiction or model of the early Andean

state, at least as a highland model, we may approach the problem of the household in a

fresh manner. The household was conscribed in relation to its specific characteristics.

Then, perhaps, we may begin to understand the dialectics of this relationship.

The outlined theoretical perspectives, however, all lack a more detailed attempt at

studying the dialectics between household units and political systems, for example the

state. Instead, state and household are considered to be autonomous, or the state is

considered an all-embracing phenomenon. I will follow another line, and try to

distinguish between different types of households, their specific character, and their

interrelations. This is a necessary pre-requisite for understanding the relation of

households to the emerging states.

3.2.2 Household variation

I cannot make any substantial theoretical discussion on the household in this report.

However, I will make some basic statements that will be used as a basis for future work.

A. A household may consist of a nuclear family, but some sort of extended family is

as common as the nuclear family group. However, I think it is useful to make a dividing

line between societies in which the household level is only one of several groupings, and

societies in which the household is the basic institution. Then both modern industrial

society and societies like that of the hunting-gathering-harvesting Paviotso fall into the