Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Julie Carlson - Unfolding Female Minds - Excerpts

Încărcat de

audreysparklingTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Julie Carlson - Unfolding Female Minds - Excerpts

Încărcat de

audreysparklingDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

from Unfolding Female Minds

*** Such insights regarding the interactivity of melancholy and writing are scripted into

The Wrongs of Women; or; Maria from the start. That book is devoted to delineating the wrongs

suffered by women who love and is composed almost entirely of scenes of reading, writing, or

storytelling. It would be hard to miss the texts emphasis on the first dimension, already

highlighted in the title. The first page depicts Maria both lamenting that her baby is a daughter

and anticipating the aggravated ills of life that her sex rendered almost inevitable, anticipations

that are actualized in all subsequent female stories in the text (by Jemima, the lovely maniac,

the landlady, Maria)(85). On these grounds, too, Wrongs of Women equates marriage with

slavery and imprisonment, implying that major social institutions are invested in female

confinement. But the text is similarly relentless in its focus on narration and the interrelation it

establishes between loving and narrating ones story. Chapter 1 ends with Jemima procuring for

Maria some books and implements for writing, which are instrumental in the attainment and

redirection of her love (89). The only bright spots in any of the womens personal stories involve

moments of reading or literary converse. This is especially true for the working-class Jemima,

whose status as mistress to a literary libertine provides the only respite in her tale of misery and

her only means of rising above it. The answer to your often-repeated question, Why my

sentiments and language were superior to my station? is that I now began to read (113). This

linkage-emphasized in the libertine profiting from the criticism of unsophisticated feeling by

reading to Jemima his productions, previous to their publication suggests that womens fates

are tied to their ability to shape stories, especially regarding the misery that their reduction to

objects of love consigns them (114). But the connection works both ways: articulating this

misery is key to changing it through publicizing new stories by women. Without this emphasis,

the text sounds defeatist about the prospects for women who love. Instead Wrongs presents

reading and writing as highly erotic activities and the best hopes for social reform.

*** In this regard, Wrongs of Women is profitably read as a treatise on sex education that

treats each term as important to educing the other. Its basic message is that society needs to be

re-educated about the practices and meanings of sex so that sexual activity does not dehumanize

individuals, especially women. The text does not argue against sex or its pleasures but against

sexual practices that rigorously oppose body to mind or male to female in the degree of pleasure

to which either body is entitled. [Women] cannot, without depraving our minds, endeavour to

please a lover or husband, but in proportion as he pleases us (145). Passion and intellect must be

equally satisfied in physical acts of love, for the culture of the heart ever, I believe, keeps pace

with that of the mind (116). These are strikingly emancipated claims, which, by linking equality

to womens share in sexual pleasure, should qualify assertions of the chasteness, even

prudishness, that characterizes the Wollstonecraftian heroine. Equally forward-looking is this

texts efforts to promote the pleasures of mental arousal and to instruct persons about the benefits

and dangers of loving by the book. As we will see, even if the genre of book (the novel of

sentiment) is ultimately censured for mischaracterizing love, the notion that books play a

stimulating role in love is never retracted. Nor does that stimulation remain on a cerebral plane.

Maria and Henry not only fall in love through marginal textual exchanges but the passion of

those exchanges anticipates, by at once postponing and preparing for, their sexual union. When

the two finally meet in person, the reserve that makes their conversation appropriate for all

the world to have listened in on is only broken when, in discussing some literary subject,

flashes of sentiment, inforced by each relaxing feature, seemed to remind them that their minds

were already acquainted (100). This activation of a former meeting of the minds, an accord

strengthened by Darnfords intervening acquaintance with the written narrative of Marias life,

triggers the physical union to which both parties consent. In fact, it is the grounds of consent.

It is true that, once triggered Wrongs of Woman then falls silent on the physical pleasure

of sex. Comments on the scene instead focus on the effects on Marias imagination, perhaps to

suggest that the pleasures of sex are never simply physical, as suggested in the definition of

voluptuous. By way of contrast, Wrongs is graphic in its portrayal of the prospect of

unsatisfactory sex, treating the reader to disgusting visions of Marias libertine husband. I now

see him-the same him whose tainted breath, pimpled face, and bloodshot eyes formerly

nauseated Maria-lolling in an arm-chair, in a dirty powdering gown, soiled linen, ungartered

stockings, and tangled hair, yawning and stretching himself (139-140). It is as if Maria forces

her readers to feel-and thus share-her revulsion as part of a visceral campaign to support the

moral necessity of divorce. The moral case rests on exposing the violence done to a womans

sensibilities in forcing her to continue to have sex with such a man. The more sensitive the

woman, the more damaging is the mandate that she fulfill her wifely duty. When I recollected

that I was bound to live with such a being for ever-my heart died within me; my desire of

improvement became languid, and baleful, corroding melancholy took possession of my soul

(145-46). No wonder those who deny women recourse to divorce are termed cold-blooded

moralists. Not content to bastille women for life, they entomb women by forcing them to

turn their hearts to stone, and in so doing extinguish that fire of the imagination, which

produces active sensibility, and positive virtue (144, original emphasis).

Whether depicted through positive or negative means, then, Wrongs of Woman wants sex

to retain (actually, find or regain) its mental and imaginative features. Sex without mind, her

definition of libertinism, is brutish precisely in robbing persons of their recourse to fantasy.

Indeed, the prospect of being enchained to a brute turns a woman to stone. On the other hand,

good sex, according to this text, both fosters and necessitates imaginative activity. There was

one peculiarity in Marias mind: she...had rather trust without sufficient reason, than be for ever

the prey of doubt (173). But affirming such visions of sex confronts several obstacles, one of

the most basic being novelistic portrayals of women as mindless, though this with an added

twist. The mindlessness that this text confronts concerns mindless reading, the passive absorption

of sentimental fiction. In Wollstonerafts eyes, such passivity not only keeps women stupefied

and therefore acquiescent in their unhappiness as wives but also focuses their erotic desires on

romance heroes whose unrealistic features are the product of limited male fantasy. Wrongs aims

to redress both situations. In the details of its plot and the interlocking structure of its narration, it

transforms the reading of fiction into an activity that forces women both to think and to

reconsider their options.

The texts seriousness about the need to alter practices and notions of sex is underscored

by its series of framing devices-especially that of Maria writing her life story to her infant

daughter in the event that she might be unable to parent her in person. That the instruction

concerns the susceptibility of erotic attraction to redirection is clear from the amatory education

that her memoir plots. Maria aims to teach her daughter how to make more satisfying choices in

love by relating not only how a different partner (first George, then Henry) affects the daily

features of her existence but also what caused her to be attracted to George in the first place: an

overactive fancy, which, schooled on books and her uncles unworldly conversations, ma[d]e

me form an ideal picture of life (126; see 131,137). Maria writes against this idealizing of

reality, even if what she narrates is caused by repeated errors of the sort. By admitting and

learning from her mistakes and then relating them to her daughter, Maria seeks to improve the

next generations happiness in love. Such improvement requires that women first break through

the secrecy surrounding sex, a secrecy that is fundamental to making sex appear sacred and too

intimate for public discourse. For this habit of viewing sex as the most private or personal

aspect of a couples relationship strengthens the marital despotism from which the wrongs of

woman stem. It keeps women from admitting to themselves, let alone to others, that their sex

lives are less than ideal and thus prevents them from banding together to change things-including

pursuing their erotic desires for each other. As the scene with her landlady shows, the sexual tie,

precisely when it is the only palpable demonstration of a husbands connection to his wife, is the

primary threat to female solidarity. It impedes womens desires to view themselves as thinking

individuals because it is not in their interest to do so.

At the same time, Wrongs of Woman retracts the contention advanced in Rights of

Woman that those wives who are unhappy as lovers make the best mothers. This mother writes to

her daughter to vindicate and broadcast her status as adulterous lover in order to safeguard her

daughters right to a sexually satisfying marriage. In the domain of marriage at least, her

message is basically never to forego desire. Acquire sufficient fortitude to pursue your own

happiness. Do not waste years in deliberating, after you cease to doubt. To fly from

pleasure is not to avoid pain (123). The protestant vocabulary should not overshadow the

underlying message regarding a wifes right to sexual happiness. Truly immoral because it is

weak-minded and therefore demeaning is retaining the cloke of matrimony on a body that has

gone elsewhere (157).

We do not have to wait for the conclusion to this text, or its lack of a conclusion, to worry

about the rationality or plausibility of these reformulations of love. The fragments of possible

endings that Godwin appends to his edition of this text suggest that Henry will prove

disappointing in any number of ways. They also suggest that lessons, like lives, have no assured

or predictable ends. But here, too, the novel anticipates our skepticism, by situation these scenes

of instruction in a madhouse. This admission, I contend, rather than any lessening of

Wollstonecrafts feminist convictions, constitutes the major difference between Rights of Woman

and Wrongs of Woman, a difference that is consistent with the implications of the shift in titles

from rights to wrongs and the latter texts narrowing of focus to marital despotism as the

chief problem obstructing womens attainment of rights. Not that Rights of Woman is ever

sanguine about the ease with which cultures alter their foundations, but it is enlightened in

assuming the efficacy of demonstrating the necessity and benefits of change. This aspect of

Enlightenment dogma is what Wrongs of Woman recants. By losing what is presented as an

irrefutable case for the rational, moral, and sensible benefits of divorce to both parties, Wrongs

exposes societys investment in the repression of women. More than ignorance or indifference

perpetuates female retardation; the most cherished social institutions of the West are established

to ensure that women do not advance. But even this degree of pessimism (i.e., realism) is

tempered by the texts understanding of the power of truth, a power that depends on redefining

the nature of truth. The best hope for positive change lies in telling less idealized or saccharine

stories above love. ***

Carlson, Julie A. Englands First Family of Writers: Mary Wollstonecraft, William Godwin,

Mary Shelley. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2007. 30-40. Print.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Dted2 TeluguDocument193 paginiDted2 Telugureddy331Încă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Preschool Business PlanDocument13 paginiPreschool Business PlanPrem Jain100% (2)

- American Pop IconsDocument132 paginiAmerican Pop IconsJanek TerkaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aruba SD-WAN Professional Assessment Aruba SD-WAN Professional AssessmentDocument2 paginiAruba SD-WAN Professional Assessment Aruba SD-WAN Professional AssessmentLuis Rodriguez100% (1)

- Inverse VariationDocument4 paginiInverse VariationSiti Ida MadihaÎncă nu există evaluări

- RPMS SY 2021-2022: Teacher Reflection Form (TRF)Document3 paginiRPMS SY 2021-2022: Teacher Reflection Form (TRF)Argyll PaguibitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Catharine, or The BowerDocument27 paginiCatharine, or The Boweraudreysparkling100% (1)

- "Henry and Eliza" Reading TextDocument4 pagini"Henry and Eliza" Reading TextaudreysparklingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jane Austen's The Watsons Reading TextDocument36 paginiJane Austen's The Watsons Reading TextaudreysparklingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Catharine, or The Bower (With Annotations)Document28 paginiCatharine, or The Bower (With Annotations)audreysparklingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mary Wollstonecraft "A Vindication of The Rights of Woman" (1792)Document52 paginiMary Wollstonecraft "A Vindication of The Rights of Woman" (1792)audreysparklingÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Watsons E-TextDocument34 paginiThe Watsons E-TextaudreysparklingÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Watsons E-TextDocument34 paginiThe Watsons E-TextaudreysparklingÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Vindication of The Rights of WomanDocument23 paginiA Vindication of The Rights of WomanaudreysparklingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mary Wollstonecraft - A Vindication - From Chapter 13Document2 paginiMary Wollstonecraft - A Vindication - From Chapter 13audreysparklingÎncă nu există evaluări

- CDC OBE Syllabus NSTP1 Mam QuilloyDocument7 paginiCDC OBE Syllabus NSTP1 Mam QuilloyJose JarlathÎncă nu există evaluări

- BSI ISO 50001 Case Study Sheffield Hallam University UK EN PDFDocument2 paginiBSI ISO 50001 Case Study Sheffield Hallam University UK EN PDFfacundoÎncă nu există evaluări

- SP - Building ConstructionDocument9 paginiSP - Building ConstructionYaacub Azhari SafariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Good HabitsDocument1 paginăGood HabitsamaniÎncă nu există evaluări

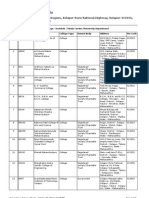

- InstituteCollegeStudyCenter 29102012014438PMDocument7 paginiInstituteCollegeStudyCenter 29102012014438PMAmir WagdarikarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Moot Court Competition Rules of ProcedureDocument4 paginiFinal Moot Court Competition Rules of ProcedureAmsalu BelayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jack Welch: Navigation SearchDocument12 paginiJack Welch: Navigation SearchGordanaMrđaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Traditional Lesson Plan 2nd QuarterDocument4 paginiTraditional Lesson Plan 2nd QuarterHappy Delos Reyes Dela TorreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Compiled Sop, Sos, Sad, Chapter IIDocument8 paginiCompiled Sop, Sos, Sad, Chapter IIJason Mark De GuzmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Google Innovations: Name Institution DateDocument5 paginiGoogle Innovations: Name Institution DateKibegwa MoriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vlogging As The Tool To Improve Speaking Skills Among Vloggers in MalaysiaDocument12 paginiVlogging As The Tool To Improve Speaking Skills Among Vloggers in MalaysiaZulaikha ZahrollailÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nicholas Aguda - CertificatesDocument13 paginiNicholas Aguda - CertificatesRuby SavellanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sharif 2006Document228 paginiSharif 2006Mansoor Aaqib MalikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foresight PDFDocument6 paginiForesight PDFami_marÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mqa 1Document1 paginăMqa 1farazolkifliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Building High Performance Teams Stages of Team Development Characteristics of A High Performing Team Benefits of A High Performing TeamDocument12 paginiBuilding High Performance Teams Stages of Team Development Characteristics of A High Performing Team Benefits of A High Performing TeamKezie0303Încă nu există evaluări

- Correct Answer: RA 7160Document5 paginiCorrect Answer: RA 7160Tom CuencaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technical Writing Course Manual, Spring 2021Document34 paginiTechnical Writing Course Manual, Spring 2021rajdharmkarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cognitive Diagnostic AssessmentDocument43 paginiCognitive Diagnostic AssessmentReza MobashsherniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Balagtas National Agricultural High School: Tel. or Fax Number 044 815 55 49Document4 paginiBalagtas National Agricultural High School: Tel. or Fax Number 044 815 55 49Cezar John SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ek Ruka Hua FaislaDocument2 paginiEk Ruka Hua FaislaAniket_nÎncă nu există evaluări

- DLSU HUMAART Policies (Third Term 2013)Document3 paginiDLSU HUMAART Policies (Third Term 2013)Mhykl Nieves-HuxleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6 Designing A Training SessionDocument34 pagini6 Designing A Training SessionERMIYAS TARIKUÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study On Students Sucide in KOTA CITYDocument53 paginiA Study On Students Sucide in KOTA CITYLavit Khandelwal100% (1)