Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

9leading The Learning Organization

Încărcat de

WaclawqTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

9leading The Learning Organization

Încărcat de

WaclawqDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Leading the learning organization: portrait of four

leaders

James R. Johnson

Purdue University, Calumet, Hammond, Indiana, USA

Introduction

The topic of the learning organization has

recently commanded a great deal of

attention. DiBella and Nevis (1998) wrote that

the learning organization is an advanced

state of organizational development. Senge's

(1990a) writing was an important

contribution to the avalanche of literature on

the subject.

Although the literature base pertaining

to learning organizations is expansive,

the vast majority of the writing is

descriptive in nature. Few authors and

researchers have offered suggestions to

senior managers on how to transform

their organization into a learning

organization.

Questions remain as to how senior

managers and chief executive officers (CEOs)

might apply specific leadership actions and

behaviors in order to foster organizational

learning. Argyris (1992, p. 1), commenting on

barriers to organizational learning, stated

that most

. . . researchers did not focus upon producing

actionable knowledge on how to reduce or

lower these barriers. In those cases where

they did, the advice was either disconnected

from the world of practice, or, when examined

carefully, the advice could actually

strengthen the very barriers that were

supposed to be overcome.

Kim (1993, p. 37) provided further evidence of

this ambiguity by writing that

``organizational learning has gained a lot of

attention, but there is little agreement on

what organizational learning means and

even less on how to create a learning

organization''.

The objective of this research was to

capture the ``perceptions and experiences''

(Locke et al., 1993, p. 99) of leaders who have

embraced the concept of the learning

organization.

Literature review

Two bodies of literature are involved here:

one vast, one relatively new. At the

intersection of the two lies very little and is

the subject of this research.

The learning organization

A learning organization must have as a

central tenet the commitment to help people

``embrace change'' (Senge et al., 1994, p. 11).

Learning organizations are designed to

anticipate and react to changing external and

competitive environments in a positive and

proactive manner. They help to institute

internal organizational structures that are

better able to respond to the turbulence of

change (Watkins and Marsick, 1993). They do

not happen automatically but require a deep

commitment to building required skills

throughout the workplace. Watkins and

Marsick (1993,p. 1) indicated that a long-term

commitment must be made at the absolute

pinnacle of the organization. The learning

organization ``will remain a distant vision

until leadership capabilities they demand are

developed'' (Senge, 1990a, p. 22).

But what are these leadership capabilities

and how, specifically, can they be developed?

The concept of leadership is nearly as

ambiguous as that of the learning

organization. Wheatley (1992, p. 12) called

leadership ``an amorphous phenomenon that

has intrigued us since people began studying

organizations'', and Bennis and Nanus (1985,

p. 6) labeled leadership as the ``LaBrea Tar

Pits'' of organizational study.

Watkins and Marsick (1996) stated that

three frameworks are useful for examining

the 22 cases contained in their edited work, In

Action: Creating the Learning Organization.

These three frameworks, from the simplest to

the most complex, are those of:

1 Watkins and Marsick (1993);

2 Pedlar et al. (1991); and

3 Senge (1990a).

The research register for this journal is available at

http://www.emeraldinsight.com/researchregisters

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

http://www.emeraldinsight.com/0143-7739.htm

[ 241]

Leadership & Organization

Development Journal

23/5 [2002] 241249

# MCB UP Limited

[ISSN 0143-7739]

[DOI 10.1108/01437730210435956]

Keywords

Leadership, Learning organizations,

Organizational learning,

Organizational development

Abstract

The phrase ``learning organization''

has existed in the literature for

several decades. Senge popularized

the term in the 1990s; however,

other writers have made significant

contributions to this topic. The

leadership literature, although vast,

lacks specificity. At the

intersection of these two concepts,

the literature lacks a needed link

that describes the specific actions

that a leader can take to achieve

the transformation to a learning

organization. This paper examines

the actions that a leader can take

in order to transform an

organization into a learning

organization and studies four

leaders of widely diverse

organizations. The research

indicated that leaders who were

successful in implementing the

learning organization concept used

it as the solution to a business

problem, while devoting time and

attention to the transformation.

The findings have widespread

implications for practitioners, adult

educators and for future research.

Received: November 2001

Accepted: March 2002

This paper is an adaptation

of an unpublished doctoral

dissertation, partially

fulfilling the requirements

for the Doctor of Education

degree at Northern Illinois

University, DeKalb, IL, USA.

These three frameworks, in addition to two

others, captured the essence of the learning

organization literature and were used in this

study to define the concept of the learning

organization as a state of organizational

existence.

Watkins and Marsick (1993, p. 8) offered the

simplest definition when they defined a

learning organization as one ``that learns

continuously and transforms itself''.

Pedlar et al. (1991, p. 1) defined the learning

company as ``an organization that facilitates

the learning of all of its members and

continuously transforms itself in order to

meet its strategic goals''. Senge's (1990a)

definition is the most complex. He defined

the learning organization as one:

. . . where people continuously expand their

capacity to create the results they truly

desire, where new and expansive patterns of

thinking are nurtured, where collective

aspiration is set free, and where people are

continually learning how to learn together

(Seng, 1990a, p. 7).

Although these definitions capture the

fundamentals of the learning organization,

two others deserve note and add clarity to the

concept. First, Marquardt (1996, p. 80) defined

the learning organization as one ``which

learns powerfully and collectively and is

continuously transforming itself to better

collect, manage, and use knowledge for

corporate success''. This definition provides

robustness to the organizational learning

process, while adding the notion that

knowledge gained can successfully be

managed.

Second, Garvin (1993, p. 80) described the

learning organization as one ``skilled at

creating, acquiring, and transferring

knowledge, and at modifying its behavior to

reflect new knowledge and insights''. Key

insights provided in this definition are

knowledge transfer and behavior

modification.

Widely cited in the literature were such

diverse organizations as Shell Oil, Motorola,

TRW Space and Defense Group (Redding and

Catalanallo, 1994), Arthur Andersen, Caterair

International, Royal Bank of Canada

(Marquardt, 1996), Johnsonville Foods, and

Chaparral Steel (Watkins and Marsick, 1993).

All of these organizations have achieved the

transformation to learning organization

status.

Learning organizations are continually

seeking data from the environment, are fluid

and adaptable, and learn from their previous

experiences. They share knowledge and

contain systems and processes for sharing

knowledge and information.

Leadership

Heilbrun (1994) pointed out that rigorous

study of the leadership phenomenon began

with the work of sociologist Max Weber in

the early part of this century and that the

study of leadership can be divided into three

stages. The earliest stage attempted to

identify traits of leaders. The next stage

focused on the behavior of leaders, and the

third and current stage centers on the

interactions between leaders and those they

lead. Heilbrun (1994) went on to say that the

future of leadership studies might lie in the

understanding that the most significant

aspects of leadership are far beyond the

ability to study them.

Many hundreds or even thousands of

definitions of leadership exist, ranging from

the abstract to the simple. Locke et al. (1991,

p. 2) offered one definition: ``we define

leadership as the process of inducing others

to take action toward a common goal''. Bethel

(1990, p. 6) proposed a more precise definition

of leadership as simply ``influencing others'',

and Loeb (1994, p. 242) stated that ``leaders ask

the what and why questions, not the how

question''.

However, another current definition of

leadership was provided by Senge (1996,

p. 36), who defined leaders as people ``who are

genuinely committed to deep change in

themselves and in their organizations''. The

most useful definition, though, was provided

by Bennis (1984, p. 19), who noted that

``leaders are people who do the right things;

managers are people who do things right''.

This separation of leaders from managers

takes on great importance. Bennis and Nanus

(1985, p. 21) clarified this when they wrote

that the ``problem with many organizations,

and especially the ones that are failing, is

that they tend to be overmanaged and

underled''.

Models of leadership have existed for as

long as the subject has been studied. One

leadership model is worthy of discussion.

Jack Welch, former chairman and CEO of

General Electric (cited in Childress and

Senn, 1995) created a model that utilizes

values results (see Table I). A type I leader,

according to the Welch model (Childress and

Senn, 1995) achieves results when holding

values sacred. This is the ideal leader. A

type II leader is also easily identified. This

leader does not meet the expected results nor

does he/she hold the values as sacred. The

type III leader has the values but does not get

the desired results. Welch (cited in Childress

and Senn, 1995) stated that these leaders were

due a second chance to succeed because of

their values orientation. The type IV leader

achieves the results but does not share in the

[ 242]

James R. Johnson

Leading the learning

organization: portrait of four

leaders

Leadership & Organization

Development Journal

23/5 [2002] 241249

values. Welch stated that these leaders will

not make the grade over the long run. For

years, organizations looked the other way as

the type IV continued to achieve results in

unorthodox ways.

Although the discussion of leadership is

important as a foundation to this research,

the focus here is on leadership actions that

transform organizations. Burns (1978)

differentiated between transactional and

transforming leadership. Transforming

leadership, according to Burns, is the type

of leadership that raises both leader and

follower to ``higher levels of motivation and

morality'' (Burns, 1978, p. 20). This idea was

further amplified (Locke et al., 1993) to define

transformational leadership as a type of

leadership that changes organizations rather

than maintaining them in their current

state. Bennis and Nanus (1985, p. 17) defined

transformational leadership as leadership

that transforms ``intention into reality and

sustain(s) it''. Ekvall (1991, p. 22) labeled this

``change-centered'' leadership.

Bennis (1994, p. 143) wrote that leaders are,

by definition, ``innovators''. They must

envision the desired state of an organization

and take required action to enable the

organization to achieve that state. Kotter

(1990), drawing on the work of Lewin,

identified eight stages of leading change: the

first four involve reducing the forces that

lead to the status quo, the middle stages

introduce change, and the last steps

incorporate the changed state into the fiber of

the organization.

The most detailed view of transformational

leadership comes from Tichy and Devanna

(1986). They wrote that transformational

leaders revitalize organizations by

recognizing the need for change, creating the

vision for change, and enlisting the

organization in the change process.

According to these authors, transformational

leaders share seven characteristics. These

leaders:

1 identify themselves as change agents and

take responsibility for change;

2 are courageous and take risks;

3 believe in and trust people;

4 have clear values and are value-driven;

5 are lifelong learners;

6 can deal with complexity, ambiguity, and

uncertainty; and

7 are visionaries and share their vision.

Leadership and the learning organization

At the intersection of the broad concept of

leadership and the ``murky'' (Johnson, 1998,

p. 148) notion of the learning organization,

there is little to provide specific guidance.

Pagonis (1992, p. 118) wrote that this must be

accomplished ``through rigorous and

systematic organizational development''.

Senge (1993) posited that there is no formula

or seminar for creating learning

organizations.

Redding and Catalanello (1994)

recommended that pockets of learning can

form within an organization and may be

shared with the rest of the organization.

Senge (1990b) proposed that leaders need to

be responsible for learning by building

learning organizations, and Bennis (1984)

wrote that leaders must value learning.

Bennis and Nanus (1985) argued that leaders

become expert at learning in the context of

the organization, and Argyris (1991) insisted

that leaders must learn how to learn. Senge

(1990b) and others have stated that leaders

must assume the role of teacher (Denton and

Wisdom, 1991) in learning organizations.

Recently, several more prescriptive views

on this topic have emerged. Senge (1993, p. 14)

proposed that leadership is a ``distributed

phenomena'' in learning organizations rather

than being focused on top management.

Bennis (1994) offered ten factors for dealing

with change and creating learning

organizations. Leaders, according to him:

1 manage the dream;

2 embrace error;

3 encourage reflective backtalk;

4 encourage dissent;

5 possess optimism, faith, and hope;

6 understand the Pygmalion effect;

7 have a certain ``touch'';

8 see the long view;

9 understand stakeholder symmetry; and

10 create strategic partnerships and

alliances.

Marquardt (1996) proposed what is possibly

the most specific series of steps for leaders.

He provided the ``keys to success'' along with

the steps and strategies to achieve that

positive outcome. According to Marquardt

(1996, p. 211), the eight ``keys'' to a successful

Table I

Welch leadership model

Type I leader Achieves results

Holds values sacred

Type II leader Does not achieve results

Does not hold values sacred

Type III leader Does not achieve results

Holds values sacred

Type IV leader Achieves results

Does not hold values sacred

[ 243]

James R. Johnson

Leading the learning

organization: portrait of four

leaders

Leadership & Organization

Development Journal

23/5 [2002] 241249

transformation to a learning organization

are:

1 establish a strong sense of urgency;

2 form a coalition;

3 create a vision;

4 communicate the vision;

5 remove obstacles;

6 find short-term wins;

7 consolidate progress and continue

movement; and

8 anchor change to the culture.

These ``keys'' are consistent with the work of

Kotter (2002), who presented a comparable

account when he wrote that leaders must

make eight things happen in organizations

that require significant and effective change.

These eight things are:

1 instill a sense of urgency;

2 pick a good team;

3 create an enterprise vision;

4 communicate;

5 remove obstacles;

6 change fast;

7 keep on changing;

8 make change stick.

Three emergent themes

Three areas emerge from the literature base

that merit further consideration: visioning,

empowerment, and the leader's role in

learning (Johnson, 1998; Senge, 1993). The

ability to create a collective vision of the

future with other members of the

organization (Watkins and Marsick, 1993)

appears to be a crucial action for leaders

of learning organizations. Communicating

the common vision to the organization

(Wheatley, 1992) seems to be of collateral

importance. Marquardt and Reynolds (1994)

referred to the information flow throughout

the worldwide organization. Senge (1990a,

p. 353) called this the ``purpose story'' or the

``overarching explanation of why they do

what they do.'' He described the difference

between the current and the desired state as

building ``creative tension'' (Senge, 1990a,

p. 357), or the force that can move followers

toward the vision by allowing them to share

it as they understand their current reality.

A second theme that emerged from the

literature dealt with empowerment. Marsick

(1994, p. 19) defined empowerment as

``interactive, mutual decision making about

work challenges in which power for work

outcomes is truly shared''. Linda Honold,

formerly director of Member Development at

Johnsonville Foods (Watkins and Marsick,

1993, p. 208), was quoted as saying ``the

learning organization is the result of

empowerment''.

A third theme derived from the literature

involves the leader's role in learning.

Argyris (1993, p. 5) called it the competence of

``leading-learning''. Marquardt and Reynolds

(1994) indicated that the leader must model

continuous learning. Barrow and

McLaughlin (1992) indicated that this new

kind of leadership would, by necessity, tie

learning to strategy. The learning that

results is tied to the strategic objectives of the

organization, and is targeted at performance

improvement (Garvin, 1993), the highest

stage of organizational learning.

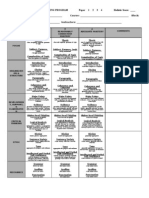

Johnson (1998, p. 146) provided a ``Learning

organisation leadership model'' that contains

an ``alignment'' of the three leadership

themes and Woolner's (1995) five-stage model

of the learning organization (see Table II). In

this model, he essentially posits that the

three leadership qualities, when blended in a

specific fashion, allow an organization to

move through the five stages as identified by

Woolner (1995). This blending of qualities,

according to the model, allows the

organization to reach the ultimate goal of the

learning organization.

Research design and methodology

Merriam and Simpson (1995) wrote that the

use of case-study research is appropriate

when a gap exists in the knowledge base.

The design of this research effort was a

qualitative case study, and the unit of

analysis was the individual leader who had

engaged in the process of transforming an

organization into a learning organization.

Data were collected primarily by using 12

semi-structured interviews. Like questions

were asked of each respondent (Merriam,

1988) and at least two other sources were

interviewed within each leader's

organization. Interviews were recorded and

later transcribed verbatim by the researcher.

Interview transcripts were coded and

analyzed by the researcher to determine

themes. In order to minimize the effects of

researcher bias, two trusted peers

continually provided feedback during the

research process.

Guiding this study were six research

questions:

1 What precipitates the decision to

transform the organization into a learning

organization?

2 Why is the learning organization concept

chosen as a desired outcome?

3 What specific actions by leaders enable

them to develop a learning organization?

4 What are the critical milestones in the

transformation process?

[ 244]

James R. Johnson

Leading the learning

organization: portrait of four

leaders

Leadership & Organization

Development Journal

23/5 [2002] 241249

5 What barriers hinder the development of

a learning organization?

6 How is progress monitored?

Creswell (1998) referred to research design as

the entire research process, not simply the

methods. Yin (1989) similarly offered that the

research design is a plan of action for getting

from the original set of questions to the

narrative containing the findings and

conclusions. In this study, the research

design begins with the research questions,

includes criteria for sample selection, data

collection and analysis, questions of validity

and reliability, and limitations of the

research, and concludes with the summary

and conclusions from the study.

Stake (1995, p. 2) indicated that the case is

``a specific, a complex, functioning thing''. In

this study, in an attempt to understand this

complex functioning, several selection

criteria were used to select the individuals or

the cases. First, there needed to be a

commitment within the organization to

become a learning organization. Second, the

organization had to be cited in the current

learning organization literature or must

have as a written strategic business objective

the learning organization outcome.

Conclusions

Conclusions drawn from the data are

organized and presented according to

research question. Additional

conclusions are presented at the end of

this section.

Research question 1

Research question 1 asked, ``What

precipitates the decision to transform an

organization into learning organization?''

The data showed that two factors contributed

to the decision to embark on a learning

organization initiative. The first was a

clearly delineated business problem. One

leader provided a vivid example of a business

problem when he said:

And it was shortly thereafter that we needed

to tap our biggest problem at that time, which

was launching new products. And we had

some launches going on at that time that were

very difficult. They just devoured the whole

division. And we said we've got to learn form

these things because we are going to be

launching a lot of new products in the future.

We can't go through this pain. So we put

together a cross-functional team involved

with launching new products. And they

immediately decided that they needed to

expand to incorporate more of the other

departments that are involved in the launch

of a new product.

The second contributing factor reported was

that learning was either implicitly or

explicitly stated in the charter of the

organization.

The commonality discovered was that the

leader must clearly identify the need for

increased learning, then articulate this need

to the organization in a way that makes sense

to them. Identification of this need may take

many forms. Regardless of whether it is

economic survival, or a core function of the

organization, this research showed that a

logical rationale must underlie the inception

of the learning organization. This notion

Table II

A learning organization leadership model

The forming

organization

The developing

organization

The mature

organization

The adapting

organization

The learning

organization

Visioning 5 X

4 X

3 X

2 X

1 X

Empowerment 5 X

4 X

3 X

2 X

1 X

Leading-learning 5 X

4 X

3 X

2 X

1 X

[ 245]

James R. Johnson

Leading the learning

organization: portrait of four

leaders

Leadership & Organization

Development Journal

23/5 [2002] 241249

supports many of the tenets found in the

leadership literature but was best presented

by Tichy and Devanna (1986) when they

wrote that leaders must recognize the need

for change. Watkins and Marsick (1993, p. 11)

provided a clear example of this need for

change when they wrote that successful

learning organizations ``realize that the wolf

is at the door''. This created a compelling

sense of urgency for the organization

(Marquardt, 1996).

Research question 2

Research question 2 asked, ``Why is the

learning organization concept chosen as a

desired outcome?'' First, the learning

organization concept was chosen as a

solution to a real or perceived problem. By

increasing the rate of internal learning,

customer solutions could be shared across

the organization.

Second, the leaders chose the learning

organization concept because it fit their

mental models. All four leaders chose this as

an organizational outcome because it fit with

their previous life experience.

Third, none of the leaders studied utilized a

specific model or framework to guide them in

their journey. Such an abstract concept as

the learning organization appeared to be

difficult for the organizations to understand.

Research question 3

Research question 3 asked, ``What specific

actions by leaders will enable them to

develop a learning organization?'' This

question rested at the center of this research

the heart and soul of the project. This

research uncovered few effective leadership

actions. A critical point, though, is that they

paid attention themselves to the learning

organization initiative. This supports the

importance of ``leading-learning,'' proposed

by Johnson (1998) in the learning

organization leadership model and drawn

from Argyris (1991, 1992, 1993). Allied to the

importance of personal attention by the

leader, was the importance of the leaders

insisting that others in the organization pay

attention to the initiative. The idea that

everyone in the organization must pay

attention to learning ran through the data. In

practice, this may mean the inclusion of

organizational learning as a strategic

planning initiative. All four leaders related

the importance of their own attention to both

the learning organization initiative and their

own personal learning. One leader typified

this best when he indicated that he attended

as many of the dialogue meetings as possibly

in order to demonstrate the importance that

he personally placed on the initiative.

Research question 4

Research question 4 asked, ``What are the

critical milestones in the transformation

process?'' As previously indicated, the

research findings showed that one leader was

the only individual studied who utilized

milestones; he set specific financial

milestones at the inception of the initiative.

However, these were not learning-related but

rather were organizational performance-

related. The assumption was that improved

organizational learning enhances

organizational performance.

Research question 5

Research question 5 asked, ``What barriers

hinder the development of a learning

organization?'' Studying these four leaders

revealed two major barriers to the learning

organization initiative. First, the leaders

must perceive a clearly defined need for

increased learning. The learning

organization notion as a solution must fit a

clearly defined existing problem; otherwise it

is simply another fad.

Second, not only must leaders make the

learning organization initiative the solution

to the problem for themselves, they need also

to make this concept fit for others in the

organization. They must perceive not only

the problem, but must also see the learning

organization initiative as the solution.

Research question 6

Research question 6 asked, ``How is progress

monitored?'' These case analyses showed that

progress needs to be measured in clear

financial terms. Clearly defined goals must

be established at the inception of the

initiative, and a reporting system needs to be

in place to track progress. This indicated that

organizational effectiveness was the ultimate

desired outcome for these leaders and it was

the foundation of the learning-organization

concept. This underlying concept was behind

the learning organization initiative.

Summary

By studying four leaders who embarked on

learning organization initiatives, this

research indicated that:

.

Leaders must be in a position of power

within the organization or must gain the

full and complete support from those in

positions of power.

.

The decision to develop a learning

organization should be based on a clearly

defined business need or business

problem.

.

The learning organization notion must be

analyzed and determined to be the

[ 246]

James R. Johnson

Leading the learning

organization: portrait of four

leaders

Leadership & Organization

Development Journal

23/5 [2002] 241249

rational solution to this business need or

problem.

.

Although the term itself is not always

used and no specific definition or

framework is utilized, the learning

organization concept needs to be shown as

a solution to a clearly articulated problem.

.

Leaders need to pay attention to this

initiative, ensure that others in the

organization are focused on it, and

institute an appropriate reward system.

This may take place in the strategic

planning process.

.

Milestones are not widely utilized, but

appropriate measurements of both

learning and the resulting organizational

performance need to be in place.

.

The major barrier to success is that the

organization does not perceive the need

for the initiative.

.

Leaders need to set up appropriate

measurements to demonstrate progress.

Implications

Successful implementation of the

learning-organization concept is dependent

upon practitioners who must reside in

positions of organizational influence or

obtain clear support from those in positions

of power. This research indicates that

successful implementation cannot be

achieved without access to positions of power

and influence. Next, a clearly defined

problem or issue must exist, and the learning

organization concept must be envisioned as a

probable solution. It is not a ``quick fix or

panacea'' (Senge et al., 1994, p. xii). Thus,

leaders must devote personal attention to the

initiative, and others in the organization

need to focus attention on it. Resources,

systems, and rewards must be devoted to this

process. And finally, leaders must find an

appropriate method of measuring success.

Just as Porter and McKibbin (1988)

asserted over a decade ago in their study of

organizational needs and business school

curriculums, adult educators need to look at

leadership with fresh eyes and review the

relevancy of the skills required in current

times. New organizational processes and new

leadership paradigms exist in today's rapidly

changing world. Several issues were

uncovered by this research:

.

The process of crafting a learning

organization cannot be initiated or

sustained by those who do not hold a

position of power within an organization.

For example, it is doubtful that human

resource directors can successfully begin

this process. Top leadership must initiate

or at least fully sanction this effort. This

was supported by Watkins and Marsick

(1993, p. xvii) when they asserted , ``You

cannot build a learning organization from

within the training department''. Leaders

must be made aware of the need for

carefully chosen strategic initiatives. The

initiative must be tied to strategy in order

for it to be successful.

.

Leaders need to have the tools for

analyzing problems and making decisions

on solutions. Wright and Noe (1996)

presented one such tool when they

described a rational decision-making

process that includes establishing goals

and objectives, identifying problems,

developing alternatives, choosing among

alternatives, and evaluating outcomes.

.

Once it is deemed appropriate for the

situation, leaders need to be skilled in

communicating the learning organization

concept in a manner that motivates others

in the organization. Kepner and Tregoe

(1997, p. 221) wrote that:

People do not resist practical and useful

ideas that promise to be supportive of

their own best interests. People do resist

obscure theorizing that has no apparent

helpful reference to their lives, threatens

them because of their strangeness, and

must be taken widely on faith.

.

Adult educators operating within

organizations need to focus on helping

people deal with change in general and

must develop the ability to identify

problem situations in their organization.

.

Learning about learning is important;

people need to know more about their

own and the organization's learning

processes.

This research looked closely at four

organizational leaders who had embraced the

learning-organization concept and offered

valuable insight into this phenomenon.

However, more research is needed to expand

the literature base. While explorative

research is not considered generalizable,

insights from this research can be viewed as

``tentative hypotheses'' (Merriam, 1998, p. 41)

that can be used as the basis of future

research initiatives. Additional research

studies of both successful and unsuccessful

learning organization implementations can

provide further insight into this nebulous

arena. Several research questions that

pertain to this topic need to be addressed:

.

What types of data can indicate the need

for increased learning in an organization?

.

In what ways can increased

organizational learning provide the

solution to this delineated problem?

[ 247]

James R. Johnson

Leading the learning

organization: portrait of four

leaders

Leadership & Organization

Development Journal

23/5 [2002] 241249

.

How can leaders engage the members of

an organization in this initiative?

.

How can successful organizational

learning be measured?

Findings from these research initiatives

then need to be empirically tested and

confirmed. In some ways, this research

indicates that theorists are working at a level

that is too abstract for practitioner leaders to

comprehend and utilize. A clear model or

framework must be developed that will allow

practitioners and adult educators to more

fully understand the learning organization.

This model needs to answer the dual

questions: ``What exactly is the learning

organization?'' and ``What specifically must

I do as a leader?'' In addition, methods need

to be developed that will allow for the

translation of organizational performance

measures into learning outcomes.

References

Argyris, C. (1991), ``Teaching smart people how to

learn'', Harvard Business Review, Vol. 69 No. 3,

pp. 99-109.

Argyris, C. (1992), On Organizational Learning,

Blackwell Publishers, Cambridge, MA.

Argyris, C. (1993), ``Education for leading-

learning'', Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 21

No. 2, pp. 5-17.

Barrow, M.J. and McLaughlin, H.M. (1992),

``Towards a learning organization'', Industrial

and Commercial Training, Vol. 24 No. 1,

pp. 3-7.

Bennis, W. (1984), ``The four competencies of

leadership'', Training and Development

Journal, Vol. 38 No. 5, pp. 14-19.

Bennis, W. (1989), Why Leaders Can't Lead,

Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Bennis, W. (1994), On Becoming a Leader,

Addison-Wesley Publishing, Reading, MA.

Bennis, W. and Nanus, B. (1985), ``Organizational

learning: the management of the collective

self'', New Management, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 6-13.

Bethel, S.M. (1990), Making the Difference: Twelve

Qualities That Make You a Leader, P.G.

Putnam and Sons, New York, NY.

Burns, J.M. (1978), Leadership, Harper and Row,

New York, NY.

Childress, J.R. and Senn, L.E. (1995), In the Eye of

the Storm: Reengineering Corporate Culture,

The Leadership Press, Los Angeles, CA.

Creswell, J. (1998), Qualitative Inquiry and

Research Design: Choosing Among the Five

Traditions, Sage Publications, Thousand

Oaks, CA.

Denton, D. and Wisdom, B. (1991), ``The learning

organization involves the entire workforce'',

Quality Progress, Vol. 24 No. 12, pp. 69-72.

DiBella, A. and Nevis, E. (1998), How

Organizations Learn: An Integrated Strategy

for Building Learning Capability, Jossey-

Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Ekvall, G. (1991), ``Change centered leaders:

empirical evidence of a third dimension of

leadership'', Leadership & Organizational

Development Journal, Vol. 12 No. 6. pp. 18-23.

Garvin, D.A. (1993, July-August), ``Building a

learning organization'', Harvard Business

Review, Vol. 71 No. 4, pp. 78-91.

Heilbrun, J. (1994), ``Can leaders be studied?'', The

Wilson Quarterly, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 65-72.

Johnson, J. (1998), ``Embracing change:

a leadership model for the learning

organization'', International Journal of

Training and Development, Vol. 2 No. 2,

pp. 141-50.

Kepner, C.H. and Tregoe, B.B. (1997), The New

Rational Manager, Princeton Research Press,

Princeton, NJ.

Kim, D.H. (1993, Fall), ``The link between

individual and organizational learning'',

Sloan Management Review, Vol. 35 No. 1,

pp. 37-50.

Kotter, J.P. (2002), ``Managing change: The power

of leadership'', Balanced Scorecard Report,

Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston,

MA, pp. 1-4.

Kotter, J.P. (1990), A Force for Change: How

Leadership Differs From Management, The

Free Press, New York, NY.

Locke, E.A., Kirkpatrick, S., Wheeler, J.K.,

Schneider, J., Niles, K., Goldstein, H.,

Welsh, K. and Chah, D. (1991), The Essence of

Leadership: The Four Keys to Leading

Successfully, Lexington Books, New York, NY.

Locke, L.F., Spirdoso, W. and Silverman, S.J.

(1993), Proposals That Work: A Guide for

Planning Dissertations and Grant Proposals,

Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA.

Loeb, M. (1994), ``Where leaders come from'',

Fortune, Vol. 130 No. 6, pp. 241-2.

Marquardt, M.J. (1996), Building the Learning

Organization: A Systems Approach to

Quantum Improvement and Global Success,

McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Marquardt, M., and Reynolds, A. (1994), The

Global Learning Organization, Irwin, Burr

Ridge, IL.

Marsick, V. (1994), ``Trends in managerial

reinvention: creating a learning map'',

Management Learning, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 11-33.

Merriam, S. (1988), Case Study Research in

Education: A Qualitative Approach, Jossey-

Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Merriam, S. (1998), Qualitative Research and Case

Study Applications in Education, Jossey-Bass,

San Francisco, CA.

Merriam, S. and Simpson, E. (1995), A Guide to

Research for Educators and Trainers of

Adults, Krieger, Malabar, FL.

Pagonis, W.G. (1992), ``The work of leaders'',

Harvard Business Review, Vol. 70 No. 6,

pp. 118-26.

Pedlar, M., Burgoyne, J. and Boydell, T. (1991),

The Learning Company: A Strategy for

Sustainable Development, McGraw-Hill,

London.

[ 248]

James R. Johnson

Leading the learning

organization: portrait of four

leaders

Leadership & Organization

Development Journal

23/5 [2002] 241249

Porter, L.W. and McKibbin, L.E. (1988),

Management Education and Development:

Drift or Thrust Into the 21st Century?,

McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Redding, J.C. and Catalanello, R.F. (1994),

Strategic Readiness: The Making of the

Learning Organization, Jossey-Bass, San

Francisco, CA.

Senge, P.M. (1990a), The Fifth Discipline: The Art

and Practice of the Learning Organization,

Currency Doubleday, New York, NY.

Senge, P.M. (1990b), ``The leader's new work:

building learning organizations'', Sloan

Management Review, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 7-23.

Senge, P.M. (1993), ``Transforming the practice of

management'', Human Resource Development

Quarterly, Vol. 4 No. 1, pp. 5-32.

Senge, P.M. (1996), ``Leading learning

organizations'', Training and Development,

Vol. 50 No. 12, pp. 36-7.

Senge, P.M., Roberts, C., Ross, R.B., Smith, B.J.

and Kleiner, A. (1994), The Fifth Discipline

Field Book: Strategies and Tools for Building a

Learning Organization, Currency Doubleday,

New York, NY.

Stake, R. (1995), The Art of Case Study Research,

Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Tichy, N. and Devanna, M. (1986), The

Transformational Leader, John Wiley & Sons,

New York, NY.

Toffler, A. (1970), Future Shock, Random House,

New York, NY.

Watkins, K.E. and Marsick, V.J. (1993), Sculpting

the Learning Organization: Lessons in the Art

and Practice of a Systemic Change, Jossey-

Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Watkins, K.E. and Marsick, V.J. (1996), ``A

framework for the learning organization'',

in Watkins, K.E. and Marsick, V.J. (Eds), In

Action: Creating the Learning Organization,

American Society for Training and

Development, Alexandria, VA.

Wheatley, M.J. (1992), Leadership and the New

Science: Learning About Organizations From

an Orderly Universe, Berrett-Koehler, San

Francisco, CA.

Woolner, P. (1995), A Developmental Model of the

Learning Organization, Woolner, Lowy and

Associates, Toronto.

Wright, P.M. and Noe, R.A. (1996), Management of

Organizations, Richard Irwin, Chicago, IL.

Yin, R. (1989), Case Study Research: Design and

Methods, Sage Publications, Newbury

Park, CA.

[ 249]

James R. Johnson

Leading the learning

organization: portrait of four

leaders

Leadership & Organization

Development Journal

23/5 [2002] 241249

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Mastering The Law of AttractionDocument82 paginiMastering The Law of AttractionNiyaz Ahmed80% (5)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Compelling Visuality (The Work of Art in and Out of History)Document256 paginiCompelling Visuality (The Work of Art in and Out of History)Rūta Šlapkauskaitė100% (2)

- The Legacy of ParmenidesDocument318 paginiThe Legacy of ParmenidesPhilip Teslenko100% (1)

- Nature of PhilosophyDocument15 paginiNature of PhilosophycathyÎncă nu există evaluări

- What makes a great trainerDocument22 paginiWhat makes a great trainerAmanda ChinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Slow LearnersDocument29 paginiSlow LearnersLeading M Dohling67% (3)

- F044 ELT-37 General English Syllabus Design - v3Document93 paginiF044 ELT-37 General English Syllabus Design - v3Cristina Rusu100% (1)

- Teacher Interview ScriptDocument5 paginiTeacher Interview Scriptapi-288924191Încă nu există evaluări

- Animal Conciousnes Daniel DennettDocument21 paginiAnimal Conciousnes Daniel DennettPhil sufiÎncă nu există evaluări

- ADDIE ModelDocument4 paginiADDIE ModelFran Ko100% (1)

- Morrow - Quality and Trustworthiness PDFDocument11 paginiMorrow - Quality and Trustworthiness PDFKimberly BacorroÎncă nu există evaluări

- STS Intro to Science, Tech and SocietyDocument21 paginiSTS Intro to Science, Tech and SocietyJabonJohnKennethÎncă nu există evaluări

- ROL and Summary and ConclusionDocument17 paginiROL and Summary and Conclusionsharmabishnu411Încă nu există evaluări

- 2.2 Learner ExceptionalitiesDocument6 pagini2.2 Learner Exceptionalitiesapi-488045267Încă nu există evaluări

- Humanities Writing RubricDocument2 paginiHumanities Writing RubricCharles ZhaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inquiry (5E) Lesson Plan TemplateDocument2 paginiInquiry (5E) Lesson Plan Templateapi-476820141Încă nu există evaluări

- TNG of GrammarDocument15 paginiTNG of GrammarDaffodilsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Smart School in Malaysia'Document10 paginiThe Smart School in Malaysia'sha aprellÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artifact - Authentic Assessment PaperDocument9 paginiArtifact - Authentic Assessment Paperapi-246369228Încă nu există evaluări

- Tok LessonsDocument3 paginiTok Lessonscaitlin hurleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan of ShapesDocument3 paginiLesson Plan of Shapesapi-339056999Încă nu există evaluări

- Teaching Reflection-1Document2 paginiTeaching Reflection-1api-230344725100% (1)

- The Mood Board Process Modeled and Understood As A Qualitative Design Research ToolDocument28 paginiThe Mood Board Process Modeled and Understood As A Qualitative Design Research ToolLuisa Fernanda HernándezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learn About Health Service ProvidersDocument2 paginiLearn About Health Service ProvidersHazel Sercado Dimalanta100% (1)

- Idt-5000 Instructional Design PlanDocument3 paginiIdt-5000 Instructional Design Planapi-336114649Încă nu există evaluări

- De Sousa Santos, Boaventura - Public Sphere and Epistemologies of The SouthDocument26 paginiDe Sousa Santos, Boaventura - Public Sphere and Epistemologies of The SouthLucas MacielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rogan & Kock. 2005. Methodology and Methods of Narrative AnalysisDocument23 paginiRogan & Kock. 2005. Methodology and Methods of Narrative AnalysisTMonito100% (1)

- Roleplaying and Motivation in TEFLDocument42 paginiRoleplaying and Motivation in TEFLGábor Szekeres100% (1)

- Reflection PaperDocument3 paginiReflection PaperCzarina CastilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- This Document Should Not Be Circulated Further Without Explicit Permission From The Author or ELL2 EditorsDocument8 paginiThis Document Should Not Be Circulated Further Without Explicit Permission From The Author or ELL2 EditorsSilmi Fahlatia RakhmanÎncă nu există evaluări